How One Pilot’s “Forbidden” Flap Setting Made Thunderbolts Climb Faster Than Fw 190s

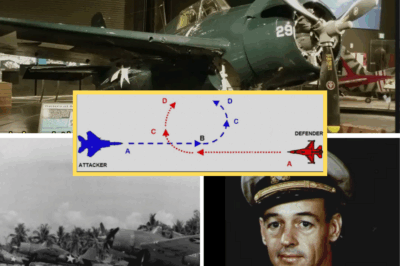

The morning of March 15th, 1944, dawned pale and brittle over the Normandy coast, a thin, cold light spilling across a sky that looked more like steel than air. Eight thousand feet above the Channel, Captain Robert S. Johnson of the 56th Fighter Group gritted his teeth and shoved the throttle of his P-47 Thunderbolt all the way forward into the war emergency range. The engine roared—a deep, furious sound that rattled through the cockpit and vibrated in his bones. Ahead of him, his wingman’s aircraft, another Thunderbolt, was breaking apart midair, pieces of silver metal spinning like leaves through the brightening sky.

The Focke-Wulf 190 that had shredded the plane pulled straight up into a perfect climb, its silhouette cutting clean against the morning sun. Johnson’s gut twisted. He hauled back on the control stick and pointed his nose skyward, his own Thunderbolt straining to follow. But he knew the truth before the climb even began. The P-47 was powerful but heavy, brutally heavy, and in a vertical contest against an FW 190, the result was always the same.

The Thunderbolt clawed upward, its big propeller biting at the air, but its momentum bled away almost immediately. The climb felt like dragging a stone uphill. The German plane, half its size, seemed to float by comparison—smooth, effortless, predatory. Johnson’s airspeed dropped. The climb angle flattened. His vision blurred for a moment as the strain pressed him into his seat. When he looked again, the 190 was already five hundred feet higher, banking lazily into position to dive back down and finish the job.

It was every P-47 pilot’s nightmare. The Germans had the advantage in everything that mattered—rate of climb, roll, acceleration. In a turning or climbing fight, the Thunderbolt was hopelessly outclassed. All Johnson could do was grit his teeth and hope to survive long enough to dive away.

Then his hand fell to the flap lever.

Every flight manual, every instructor, every pre-mission briefing had hammered home one unbreakable rule: never deploy the flaps in combat. They were for takeoffs and landings only. At high speed, the air pressure could rip them clean off the wings. Worse, they slowed the plane down, turning it into a perfect target. It was flying suicide.

Johnson hesitated only a second. Then he pulled the lever. Fifteen degrees.

The Thunderbolt shuddered as the flaps deployed, but instead of pitching forward into a stall, the aircraft suddenly seemed to catch the air like a fist gripping cloth. The nose lifted, the climb steepened, and for a heartbeat Johnson thought he’d imagined it. But the altimeter needle was rising faster—much faster. The massive plane that had always felt like a hammer dragging through the sky now surged upward like a beast unleashed.

The German pilot above him rolled into position for his attack, expecting an easy kill. What happened next would later be described in engineering reports as “aerodynamically improbable.” Johnson’s P-47 not only closed the distance—it outclimbed the Focke-Wulf. In a straight vertical contest, seven tons of American steel and armor rose faster than one of the most advanced German fighters in the world.

By the time the Focke-Wulf pilot realized what was happening, it was too late.

Within seconds, the Thunderbolt was on his tail. The German dove, desperate to escape, but Johnson already had him centered in his sights. The six .50-caliber guns roared, tracers slicing through the cold morning air. The Focke-Wulf burst into flame and fell spinning toward the Channel.

That single moment—one desperate, rule-breaking decision—would quietly change the course of the air war over Europe.

Six weeks later, the Eighth Air Force circulated a classified tactical bulletin. It reversed two years of official doctrine and ordered all Thunderbolt squadrons to train in the “Johnson Flap Technique.” The maneuver that had been forbidden, dismissed, and even mocked became standard operating procedure. And overnight, the Luftwaffe lost one of its most dependable advantages.

But in that moment, high over Normandy, none of that existed yet. There was only Johnson, gasping in his oxygen mask, his hands trembling on the stick, realizing he had just done something no one thought possible.

By early 1944, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt had already earned its reputation as the heaviest single-seat fighter in service anywhere on Earth. Fully loaded, it tipped the scales at 17,500 pounds—nearly twice the weight of a Spitfire or a Messerschmitt. Its massive Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine churned out over 2,000 horsepower, enough to propel the machine faster in a dive than any German plane could follow. It was a brute of a fighter: tough, durable, built to take punishment and bring its pilot home even after absorbing half a dozen cannon shells.

But all that power came with a cost.

The P-47’s greatest weakness was baked into its design. Its wing loading—the amount of weight each square foot of wing had to lift—was higher than almost any other frontline fighter. At 47 pounds per square foot, it needed tremendous airspeed to generate enough lift. The lighter, more agile Focke-Wulf 190, with its wide, efficient wings, could climb easily where the Thunderbolt labored.

The math was cruel. In any climbing engagement below fifteen thousand feet, the Focke-Wulf could outclimb a Thunderbolt by nearly eight hundred feet per minute. In combat, that gap was fatal. German pilots had learned to exploit it mercilessly. When a P-47 tried to chase them upward, they simply pointed their noses at the sky, climbed away, and reset the fight from above—always with the advantage of altitude, speed, and surprise.

For eighteen months, the Eighth Air Force had wrestled with this problem. The P-47’s strengths were clear: it was nearly indestructible, deadly in a dive, and capable of devastating firepower with its eight .50-caliber machine guns. Its high-altitude performance was unmatched, and its pilots learned to use those strengths with hit-and-run tactics—swooping down from above, firing, and climbing back to safety before the enemy could respond.

But bomber escort missions didn’t follow those rules.

When German fighters attacked American bombers, the P-47 escorts had to dive to meet them, plunging into chaotic dogfights at low altitude. Once down there, the Thunderbolt’s advantages vanished. It became a lumbering target, too heavy to climb away, too sluggish to turn with the German planes darting through the bomber formations. The price was staggering.

Between January and March of 1944 alone, the Eighth Air Force lost 278 Thunderbolts. Some were shot down by ground fire, some by bomber gunners in the confusion of the fights, but many were destroyed in the same deadly scenario: low-altitude climbing battles where the Focke-Wulfs and Messerschmitts could dictate every move.

Major General William Kepner, commander of VIII Fighter Command, summarized the crisis in a grim February report: “The P-47 is without question the finest high-altitude fighter in our inventory. Below ten thousand feet, against the FW-190, it is at a severe disadvantage in any maneuver requiring rapid climb performance.”

Republic Aviation’s engineers in New York knew the problem inside and out. They’d been chasing a solution for months—experimenting with paddle-blade propellers for greater thrust, water injection systems for temporary power boosts, even reworking the wing design for better lift. The ideas were sound, but none could be implemented quickly enough to help the men already flying and dying over Europe.

The frustration was all the greater because the Thunderbolt’s engine, on paper, was vastly superior. The Double Wasp generated nearly twice the horsepower of the BMW 801 radial engine in the Focke-Wulf. By all logic, more power should have meant a better climb. But power alone couldn’t overcome physics. The Thunderbolt’s weight and high wing loading made it an unwilling climber, no matter how hard its engine roared.

At Wright Field, test pilots had tried everything—adjusting propeller pitch, increasing manifold pressure, fine-tuning the fuel mixture. They squeezed out small improvements, but nothing that changed the outcome of a fight. The laws of aerodynamics seemed absolute.

And then, on that March morning over Normandy, one pilot ignored them.

Captain Robert S. Johnson wasn’t an engineer. He wasn’t a scientist or a test pilot with a stack of data charts. He was just a man in a desperate situation who made a choice his training told him not to make. He pulled the flap lever in combat. He did the forbidden thing.

And somehow, impossibly, it worked…

Continue below

March 15th, 1944, 8,000 ft above the Normandy coast, Captain Robert S. Johnson watches his wingman’s P47 Thunderbolt disintegrate. The Faulk Wolf 190 that killed him pulls up vertically, effortlessly climbing away from Johnson’s own aircraft. Johnson pushes his throttle to war emergency power and hauls back on the stick.

The thunderbolt, all seven tons of it, claws for altitude. The German fighter climbs faster. This is the nightmare scenario every Thunderbolt pilot dreads. The FW190 can outclimb them, out roll them, and tear them apart before they can respond. Johnson’s airspeed bleeds away as his nose points skyward.

The German is already 500 ft above him, banking to dive back down for the kill. Johnson’s hand moves to the flap lever. Every flight manual, every briefing, every instructor has hammered home the same warning. Never deploy flaps in combat. They’ll tear off at high speed. They’ll slow you to a crawl. They’ll make you a sitting duck. He pulls the lever anyway.

15°. The thunderbolt lurches upward like someone cut its chains. In the 30 seconds that follow, Johnson does something that Air Force technical manuals will later classify as aerodynamically impossible. He outclims a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 in a straight vertical contest, gets on its tail, and sends it spinning into the channel in flames.

Within six weeks, every P47 squadron in the European theater will receive a classified tactical bulletin reversing two years of official doctrine. The forbidden technique will become standard procedure, and the Luftwaffe’s most reliable tactical advantage will evaporate overnight. By early 1944, the Republic P47 Thunderbolt had established itself as the heaviest singleseat fighter in operational service.

anywhere in the world. Weighing 17500 lb, fully loaded, powered by the massive Pratt and Whitney R2800 double Wasp engine producing 2,000 horsepower, the Thunderbolt could absorb catastrophic battle damage and dive faster than anything the Luftwaffe could field. But it couldn’t climb worth a damn. The problem was simple physics.

The P47’s wing loading, the aircraft’s weight divided by its wing area, was substantially higher than any German fighter. At 47 lbs per square foot, the Thunderbolt needed more air speed to generate the same lift that a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 could produce at lower speeds. In practical terms, this meant that in any climbing engagement, the German fighter held a decisive advantage.

The statistics backed up what pilots already knew viscerally. In vertical maneuvers below 15,000 ft, the FW190 could outclimb a Thunderbolt by approximately 800 ft per minute. In combat, this translated to life or death. A German pilot with any tactical sense could simply climb away from pursuing thunderbolts, reset the engagement on his own terms, and dive back down with altitude and energy advantage firmly in hand.

For 18 months, Eighth Air Force P47 squadrons had struggled with this fundamental performance deficit. Tactical doctrine compensated by emphasizing the Thunderbolts strengths. high altitude performance, diving speed, and devastating eight gun firepower. Pilots were taught to maintain altitude advantage, never allow themselves to be drawn into low altitude turning fights, and use hit-and-run tactics that played to the aircraft’s rugged construction and superior dive performance.

The problem was that bomber escort missions didn’t always allow such tactical flexibility. When German fighters dove through bomber formations, Thunderbolt escorts had to follow them down. Recovery to altitude then became a desperate race against physics with FW190s and BF-1009s holding every advantage.

Between January and March 1944, the 8th Air Force lost 278 P47s, while many fell to ground fire and bomber defensive crossfire. A significant portion died in low altitude engagements where German fighters could dictate the terms. Major General William Kepner, commanding eight fighter command, wrote in a February 1944 assessment.

The P47 is without question the finest high altitude fighter in our inventory. below 10,000 ft against the FW190. It is at a severe disadvantage in any maneuver requiring rapid climb performance. Republic Aviation’s engineers understood the problem. The company had proposed various modifications, paddle blade propellers for improved thrust, water injection systems for emergency power boosts, even experimental wing designs with increased area. all showed promise.

None could be implemented quickly enough to affect the current operational crisis. What made this situation particularly frustrating was that the P47’s massive engine produced more raw horsepower than any German fighter. The R2800 generated nearly twice the power of the BMW 801 radial in the FW1 to90. Yet in climbing combat, power alone couldn’t overcome the tyranny of wing loading and aerodynamic efficiency.

Test pilots at right field had explored every possible avenue for improving climb performance within the aircraft’s existing design. They’d experimented with propeller pitch settings, manifold pressure limits, and various combinations of mixture settings. Marginal improvements resulted, but nothing that fundamentally altered the climb rate equation.

The solution, when it came, wouldn’t emerge from engineering analysis or wind tunnel testing. It would come from a desperate pilot in a life or death situation, disregarding everything he’d been taught about proper aircraft handling. German fighter pilots had learned to respect the Thunderbolt strengths while exploiting its weaknesses with near scientific precision.

Luftwaffe tactical bulletins from early 1944 reflected this calculated assessment. One captured document from Yagashv 26 instructed pilots, “The P47 is dangerous only when it holds altitude advantage. Force the American to climb and you control the engagement. They weren’t wrong. Oberlitant Joseph Pipsiller, commanding JG26, had built his defensive tactics around this principle.

When Thunderbolt escorts appeared, his fighters would make aggressive head-on passes through bomber formations, then dive away and climb back to altitude while American fighters struggled to pursue. The technique worked with devastating consistency. Eighth Air Force pilots understood they were fighting with one hand tied behind their backs.

Lieutenant Colonel Hub Zama, commanding the 56th Fighter Group, wrote in his after-action report from a March 8th mission. We splashed three 190s but lost two aircraft to a climbing scissors maneuver that we simply couldn’t counter. The Germans know our aircraft better than we do. American training doctrine compensated by teaching energy management rather than turn performance.

Fighter schools emphasized maintaining speed, avoiding sustained turning engagements, and using the Thunderbolts superior dive performance to escape unfavorable situations. The phrase repeated in every briefing was boom and zoom. Dive in fast, hit hard, climb away using speed, never get slow. But bomber escort missions made that doctrine nearly impossible to execute perfectly.

When German fighters attacked B17 formations from above, Thunderbolt pilots had no choice but to engage, regardless of altitude or energy state. They’d dive down to break up the attacks, succeed in driving the Germans away, then face the agonizing climb back to escort altitude while FW90s circled above them like vultures.

Several squadrons had experimented with keeping sections of fighters at maximum altitude as top cover while others escorted the bombers directly. This helped, but it meant fewer fighters directly protecting the bombers, and German tactics adapted quickly. They’d send decoy formations to draw down the high cover, then strike with fresh fighters once the Americans were committed low.

Republic’s test pilots had explored every corner of the P47’s performance envelope, or so they thought. The tactical manual was explicit about combat flap usage. Flaps may be used at speeds below 150 mph to tighten turning radius in emergency situations. Under no circumstances should flaps be deployed above 200 mph or in climbing flight.

structural failure may result. That warning had been validated in testing. Flaps deployed at high speed created massive drag and structural stress. Every pilot who flew the Thunderbolt knew the flap lever was for landing and tight low-speed turns only. Then came a combat mission that would force one pilot to violate that absolute prohibition.

What he discovered would render two years of tactical doctrine obsolete in a single engagement. Captain Robert S. Johnson was not a novice. By March 1944, the 28-year-old pilot from Lton, Oklahoma had flown 73 combat missions with the 56th Fighter Group. He’d survived being shot up so badly the previous June that he’d limped back to England with 21 cannon shell holes in his aircraft.

The Luftwaffe knew how to kill pilots. Johnson knew how to stay alive. The mission on March 15th was a standard bomber escort to aircraft factories near Paris. Johnson’s flight of four Thunderbolts was providing close cover for the lead B17 box when German fighters appeared at 1:00 high. Standard engagement. The FW190s dove through the formation, firing, then pulled up hard to climb away.

Johnson’s wingman, Lieutenant James L. Stewart, pursued one of the 190s down through the bomber formation. Johnson followed, calling warnings as Steuart fixated on his target. The problem with target fixation is you stop checking your 6:00. The second FW90 came from above and behind. Johnson saw it before Stuart did.

Screamed the warning over the radio, but the geometry was already wrong. The Germans 20 Mor cannon fire walked up Stewart’s fuselage. His P47 nosed over and went down, trailing smoke and pieces. The FW1 to90 that killed Stuart pulled vertical full power. Climbing away, Johnson pushed his throttle to war emergency power, 2A 535 horsepower.

Manifold pressure redlinined at 56 in. He pulled back on the stick and pointed his nose at the clouds. The thunderbolt accelerated in the climb initially using kinetic energy from the dive, but physics is unforgiving. As air speed bled off from 350 mph to 280 to 240, the climb rate decreased proportionally. The altimeter unwound 8,000 ft. 8,400 8,700.

The FW190 was already at 9,500 and still climbing hard. Johnson held the climb. His air speed dropped through 200 mph. The German was 1,000 ft above him now, banking left to reverse and dive back down. Johnson had maybe 10 seconds before those 20 mm cannons tore him apart like they’d torn apart Stewart. The control stick felt mushy in his hands.

The thunderbolt approaching the edge of its slow flight envelope. Johnson knew the energy equation was hopeless. He couldn’t outclimb the 190. He couldn’t dive away without giving the German a perfect deflection shot. turning would bleed even more airspeed and make him a stationary target. His left hand dropped to the flap lever. Every instructor’s warning echoed in his head.

Every manuals redlettered prohibition, but Johnson had flown crop dusters in Oklahoma before the war. He understood lift. More wing surface meant more lift at lower speeds. Flaps increased wing area and camber. They’d generate more lift right now at this precise moment, even if they also increased drag. He pulled the lever to 15 degrees.

The hydraulic actuators winded. The trailing edge flaps extended down and back. The thunderbolt lurched upward as if kicked from beneath. Johnson felt himself pressed down into his seat. The vertical speed indicator, which had been showing a weakening 900 ft per minute, jumped to 1,400. The aircraft’s nose pitched up further, and Johnson had to push forward on the stick to keep from stalling.

The German pilot above him saw the Thunderbolt’s sudden acceleration. His,000 ft altitude advantage shrank to 800 ft, then 600. He rolled into his attack dive, but the geometry was changing faster than he could compensate. The slowmoving target he’d expected to be lining up in his gun sight was suddenly climbing at a rate that matched his own best performance.

Johnson watched the 190 grow larger in his windscreen. His air speed held at 195 mph, dangerously slow for combat, but the flaps were generating lift that normally required another 40 mph. He reached 9800 ft, then 10,000. The German leveled off at 10,500, turning hard to regain position. But Johnson wasn’t finished climbing.

He pulled the Thunderbolts nose up another 5°. The aircraft shuttered on the edge of accelerated stall, but the flaps kept generating lift. He passed through 10,500 ft with the FW1 to90 now directly off his left wing, barely 300 ft away. Both aircraft were slow, both vulnerable. Johnson kicked right rudder, aileron coordinated, and brought his nose around.

The Germans saw the movement and snapped into a hard left roll. The FW190’s superior roll rate should have given him the advantage, but Johnson had altitude and angles now. He fired a 2- second burst from all 850 caliber Brownings, 2600 rounds per minute, convergence pattern set for 300 yd. Tracers walked across the 190s engine cowling.

The BMW 801 radial engine took multiple hits. Black smoke erupted from the cowl flaps. The German rolled inverted and pulled through toward the deck. The classic escape maneuver that should have worked because thunderbolts couldn’t follow one in a vertical dive and climb sequence. Johnson retracted his flaps, pushed his stick forward, and dove after him.

The thunderbolt accelerated quickly in the dive. This was what it did best. He closed to 250 yd and fired again. More hits stitched across the 190s wing route and fuselage. The German fighter snap rolled to the right, pieces coming off, then went into an inverted spin. Johnson pulled out of his dive at 4,000 ft and watched the FW190 hit the channel 8 mi north of DEP.

The entire engagement from Stuart’s death to the German splash had lasted 90 seconds. Johnson’s hands were shaking as he retracted his landing gear. He’d forgotten he’d dropped it as well as the flaps in his desperation to generate lift. The Thunderbolt hadn’t torn itself apart. The flaps hadn’t ripped off. Every prohibition in the manual had been wrong, or at least incomplete.

Johnson returned to Hailworth with 12 gallons of fuel remaining and a combat discovery that would change Eighth Air Force tactics for the rest of the war. When Johnson climbed out of his cockpit and described what he’d done, his squadron engineering officer initially didn’t believe him. Deploying flaps at 200 mph in a climbing attitude violated every structural limit in the P47 technical manual.

The aircraft should have experienced catastrophic structural failure or entered an unreoverable stall. But Johnson’s gun camera footage told the story. Frame by frame, the film showed the Thunderbolts sudden climb rate increase, the changing angles as Johnson matched and exceeded the FW190s vertical performance, and the final sequence where an American fighter did what American fighters weren’t supposed to be able to do.

Within 48 hours, Republic’s test pilot at Farmingdale, Mike Richie, was running flight tests with a P47D at various speeds and flap settings. What he discovered fundamentally changed the understanding of the Thunderbolts aerodynamic behavior. At speeds between 180 and 220 mph, deploying flaps to 15 degrees, increased lift coefficient by approximately 30% while only increasing drag by 20%.

The net result was a measurably improved climb rate, roughly 400 additional feet per minute at the bottom of the speed envelope, where combat often forced pilots to operate. The reason this had never been discovered in testing was simple. No test pilot had ever tried it. The manual said, “Don’t deploy flaps in climbing flight.

” Test protocols followed manual limitations. Combat pilots, trusting the manual, never experimented with techniques they’d been explicitly told would kill them. Major General Kepner ordered immediate verification through operational testing. The 56th Fighter Group assigned six pilots to conduct combat trials using flaps during climbing engagements.

Over the next three weeks, these pilots recorded 17 encounters where flap assisted climbing either enabled them to match German fighters in vertical maneuvers or gave them sufficient climb performance to avoid being trapped in disadvantageous positions. The limitations quickly became clear. Flaps at 15° worked in the 180 to 220 mph envelope.

Above 220, structural stress increased dangerously. Below 180, the aircraft was too slow for combat maneuvering. The technique required precise airspeed awareness and immediate flap retraction once the tactical situation allowed normal flight parameters to be restored. Intelligence officers realized they’d stumbled onto something the Luftwaffe couldn’t easily counter.

German fighter tactics had been built on documented P47 performance characteristics. If Thunderbolt suddenly demonstrated climb capabilities that exceeded their known specifications, German pilots would face tactical situations they’d trained to avoid. On April 12th, 1944, 8 Fighter Command issued tactical bulletin 4744, classified restricted.

The bulletin reverse the absolute prohibition on combat flap usage and provided specific guidance in climbing engagements below 250 mph. Pilots may deploy flaps to 15° to temporarily improve climb performance. Flaps must be retracted when speed exceeds 220 mph or when tactical situation permits. This technique may produce climb rates approaching 2,000 ft per minute at air speeds where normal climb performance would be significantly degraded.

The bulletin went to every P47 squadron in the 8th and 9th Air Forces. Training officers were directed to incorporate the technique into combat instruction. Engineering officers were tasked with monitoring flap actuator wear and structural stress, though initial evidence suggested the technique, properly executed, fell within the aircraft’s structural margins.

What made this discovery particularly valuable was its psychological impact. Thunderbolt pilots who’d felt disadvantaged in climbing engagements suddenly had a technique that negated German tactical assumptions. Luftwaffe pilots who’d grown confident in their ability to climb away from pursuing P47s began experiencing situations where the Americans matched their performance.

The climb advantage that German fighters had exploited for 18 months disappeared almost overnight. The statistical evidence appeared within 60 days. Between midApril and midJune 1944, 8th Air Force P47 squadrons recorded a 16% increase in FW90 kills despite flying fewer escort missions as they transitioned to ground attack roles in preparation for the Normandy invasion.

More significantly, P47 combat losses in engagements below 10,000 ft decreased by 22%. Robert Johnson survived the war with 27 confirmed aerial victories, making him one of the top American aces in the European theater. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for actions on June 26th, 1944, though the citation made no mention of his March 15th discovery.

Johnson himself rarely spoke about the flap technique, later writing that he’d simply done what seemed logical in the moment and was surprised when it became formal doctrine. The technique spread beyond the European theater. By August 1944, fifth Air Force P47 squadrons in the Pacific were using combat flaps in engagements with Japanese fighters, particularly the Nakajima Key4, which shared the FW190’s ability to outclimb standard P47 operations.

Pilot reports from the 348th Fighter Group noted that combat flaps gave them options they’d previously lacked in vertical maneuvering against the best Japanese fighters. The Luftwaffe eventually recognized that P47 climb performance had improved beyond published specifications. A captured document from September 1944 warned German pilots, “The P47 has demonstrated climb capabilities that exceed previous intelligence assessments.

Do not assume altitude superiority in climbing engagements below 4,000 m.” Postwar analysis by both Republic Aviation and the Air Force calculated that the combat flap technique likely saved between 40 and 70 Thunderbolt pilots in the European theater alone. These pilots survived engagements they would otherwise have lost or avoided situations where German fighters could dictate terms from superior altitude positions.

The discovery influenced post-war fighter design philosophy. Aircraft engineers began examining performance envelopes more critically, questioning whether conservative structural limits were leaving useful capabilities unexplored. The concept that high lift devices could enhance combat performance in ways beyond their intended function became part of fighter development methodology.

Several Korean War era jet fighters incorporated combat flap schedules into their operating manuals from initial design rather than discovering the technique operationally. The North American F86 Sabers combat flap procedures used extensively in engagements with MiG 15s drew directly from lessons learned with the P47. Ironically, the German fighters that had so dominated climbing engagements in early 1944 were themselves flying with suboptimal technique.

FW90 pilots had been trained to climb at specific power settings and air speeds that maximized engine longevity. Postwar testing of captured FBAN90s revealed they could produce even better climb performance with more aggressive power. for management, but fuel constraints and engine reliability concerns had prevented Luftwafa pilots from exploring their aircraft’s absolute performance limits.

The story of combat flap stands as one of those rare instances where a single pilot’s desperate improvisation became standard doctrine. Johnson didn’t discover an engineering flaw in the P47. He discovered that conservative peacetime testing limitations had obscured combat capabilities that existed within the aircraft’s structural margins all along.

Innovation in combat rarely comes from engineers and test pilots working in controlled conditions. It comes from desperate soldiers who lack the luxury of following approved procedures because following procedures means dying. Johnson’s discovery teaches something fundamental about the relationship between doctrine and survival.

Manuals are written by people who’ve never been shot at, refined by committees that prioritize liability over lethality and printed with prohibitions that assume perfect conditions. Combat has no perfect conditions. Combat has target fixation and closing rates and seconds to decide. Combat has Germans climbing away and dead wingmen and a flap lever your hand finds because every other option leads to the channel.

Republic Aviation built the flap system strong enough to handle combat loads. The engineers just didn’t know they’d built it that strong because no one had tried to break it the right way. The manual said, “Don’t try.” Johnson tried anyway because trying meant maybe living and following the manual meant definitely dying. March 15th, 1944.

8,000 ft above the Normandy coast. One navigation error, one split-second decision, one prohibited control input that saved one pilot and changed tactical doctrine for every Thunderbolt squadron in two theaters of war. Sometimes the most important thing you can do is ignore the manual and trust what the machine is telling you through the stick.

The manual protects the aircraft. The pilot protects himself. Superior engineering matters. Desperate innovation matters

x

Copyfish

OCR successful

OCR Result(Auto-Detect)

Translated(English)

Please select text to grab.

News

CH2 How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly

How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly The morning sky above Wake Island…

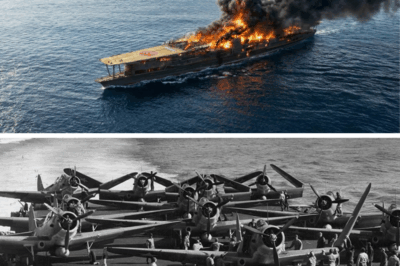

CH2 Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky The air above Rapopo…

CH2 Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons

Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons At 6:15 on…

CH2 What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History

What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History In the spring…

CH2 Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted

Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted At precisely…

CH2 Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland It…

End of content

No more pages to load