How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany was clear and cruel, a frozen blue dome scarred by the contrails of war. Five miles below, towns and fields stretched in cold silence, but up here, inside the vibrating metal belly of a B-17 Flying Fortress, there was only noise—deafening, metallic, constant. Staff Sergeant Michael Romano crouched in the tail section, entombed in aluminum and glass, the world reduced to the narrow arc of sky visible through his warped plexiglass window. His seat was little more than a slab of metal padding bolted to the frame, and the temperature had plunged to forty below zero. Every breath fogged inside his oxygen mask. Every vibration rattled his bones.

His job was simple, at least on paper: defend the bomber’s rear. In practice, it meant waiting for death to arrive from the six o’clock position—the angle every gunner feared most. The tail was the bomber’s weak spot, a funnel of vulnerability where German fighters could slip in unseen until it was too late. Romano knew this. Every gunner did. The Luftwaffe pilots called it der Sargwinkel—the coffin corner.

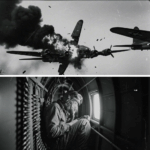

He saw the threat long before he could react: a tiny glint in the distance, moving too fast to comprehend. The speck grew until it became a predator—an Focke-Wulf 190, shark-gray against the winter sky. It rolled onto its back, slid into a shallow dive, and lined up perfectly behind Knockout Dropper, Romano’s B-17.

“Six o’clock low!” he shouted into the intercom, his voice muffled by static and oxygen hiss. He reached for the twin .50-caliber machine guns mounted in front of him, their barrels gleaming in the dim light. The aircraft shuddered under the stress of turbulence, making the guns buck in his hands like living creatures. Romano braced his knees against the fuselage, squinted through the ring-and-bead sight, and waited for the fighter to fill the circle.

That “sight,” as the Army Air Forces called it, was a cruel joke—a relic of an earlier century. Two pieces of metal, one a circle, one a post. No lead computation, no speed correction, no guidance. Just guesswork and luck. The Air Force had told him it worked. Romano knew better.

He squeezed the trigger. The twin guns erupted, filling the tail with thunder and smoke. Tracers streaked through the air, glowing red against the sky. But the line of fire passed harmlessly behind the diving fighter, the bullets curving away like fireworks fading into nothing. Romano gritted his teeth and adjusted again, but the German was faster. The FW-190’s cannons flashed—a strobe of light, then a series of horrible metallic thuds as shells punched through the bomber’s skin.

The impact sounded like a sledgehammer hitting sheet metal. The tail shivered violently. Fragments of aluminum spiraled past the window. Romano didn’t need to look to know the damage was bad. He just kept firing, hoping to scare the German off, praying one of his rounds might connect.

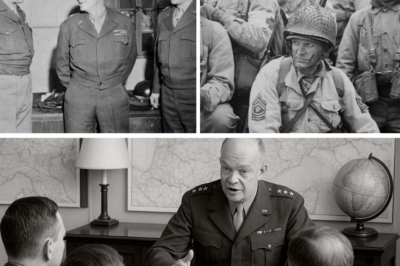

What was happening to Romano that morning wasn’t unique—it was happening across the entire formation. Two hundred ninety-one B-17s flying toward Schweinfurt, Germany, each one packed with ten men, each one under siege. It was the second raid on the ball-bearing factories—the most vital industrial target in the Reich. The mission’s planners called it precision bombing. The men who flew it would remember it as Black Thursday.

The idea that brought them here was born not from strategy, but from faith—faith in the so-called “bomber mafia,” a small group of officers who believed they could win wars from the sky. They believed their aircraft, bristling with thirteen .50-caliber guns, could defend themselves against anything the enemy sent up. They called it the Flying Fortress because that was what they wanted to believe it was—untouchable, unbreakable.

On paper, the theory made sense. In reality, it was a death sentence.

At 1:30 p.m., over the city of Aachen, the escorting P-47 Thunderbolts reached their fuel limits and turned back for England. The bombers continued on alone. For the next three hours, they would have no protection at all. The Luftwaffe was waiting—700 fighters strong. Messerschmitt 109s, Focke-Wulf 190s, even twin-engine 110s armed with rockets. It was the largest defensive ambush Germany had ever launched.

They came in waves, hundreds at a time, striking from the rear and sides, from above and below. The air turned into chaos—smoke trails, burning fuel, falling men. A B-17 would take a hit and vanish in a fireball, its wings peeling off like paper. Crews bailed out into the freezing sky, only to have their parachutes shredded by shrapnel or set ablaze by burning debris.

Romano watched one Fortress break apart ahead of him, its tail spinning away, its fuselage trailing smoke. For a moment, a single figure tumbled through the flames—arms spread wide, motionless—and then was gone. The radio was a cacophony of panic and pain. “Mayday, mayday, we’re hit! Fighters on the tail!” Then static.

By nightfall, what limped back to England barely resembled a fighting force. Sixty bombers were gone—over 600 men dead or missing. Another 138 aircraft returned too damaged to ever fly again. One out of every five Flying Fortresses that left that morning would never come home. The myth of invincible daylight bombing had been shattered.

At 8th Air Force headquarters, the mood was grim. Intelligence officers pored over after-action reports, trying to make sense of the slaughter. The statistics were brutal: tail gunners—the last line of defense—were scoring hits less than eight percent of the time. It didn’t matter how many guns a B-17 carried if the men behind them couldn’t hit a moving target at 300 miles per hour.

The Luftwaffe had learned the pattern. They called it the six o’clock low approach—the blind spot beneath the bomber’s tail. They could attack, take a few bursts of poorly aimed return fire, and then destroy the Fortress at leisure. The Army Air Force’s greatest weapon was becoming a liability.

Back in England, the frustration ran deep. Crews cursed their equipment, engineers argued over designs, and generals demanded answers. The promise of the “flying fortress” had become a bitter joke among the men who flew it. The .50-caliber guns were powerful, yes—but power meant nothing without accuracy.

At Bassingbourn Airfield, home of the 91st Bomb Group, Michael Romano understood that problem better than most. He wasn’t an engineer, or a strategist, or a hero. He was just a kid from Pittsburgh who had spent his teenage years on the factory floor before enlisting. He’d been trained for six weeks—how to clean a gun, how to clear a jam, how to aim using that miserable ring-and-bead sight. Then they sent him to war.

Romano was nineteen when he first crawled into the tail of a B-17. The veterans called it “the coffin.” You sat alone for hours, trapped in a glass bubble, staring into an empty sky that could kill you at any moment. There was no escape route, no cover, no one to talk to. The position was so cramped you couldn’t stand, and after the first hour your legs went numb. Every mission was a test of endurance and nerve.

He flew his first combat sortie on August 19th, 1943, over Gilze-Rijen in the Netherlands. Three FW-190s came at them from the rear. He fired nearly five hundred rounds. He thought he hit one of them. He wanted to believe it. But when the gun camera film came back, it showed nothing—just empty sky and wasted ammunition.

That night, sitting on his cot in the barracks, Romano couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong—not with him, but with the weapon itself. The ring sight forced him to guess where the enemy would be by the time his bullets arrived. It worked for slow-moving targets, but against fighters screaming in from multiple angles, it was worthless. He couldn’t rely on luck. Not when luck meant survival.

In the weeks that followed, as more missions ended in disaster, Romano began sketching ideas in the margins of his flight log. He wasn’t supposed to. Modifying government equipment without authorization was strictly forbidden. But he couldn’t stop thinking about it.

There had to be a better way to aim a gun.

He experimented with lines and angles, thinking about speed, distance, and deflection. He remembered something one of his instructors had said during training—that a bullet took nearly a full second to travel 1,000 yards. In that second, a fighter plane could move hundreds of feet. Hitting it wasn’t just about pointing and firing; it was about predicting where it would be.

The problem was that the Air Force’s sights didn’t predict anything. They were relics from World War I, designed for open-cockpit biplanes fighting at half the speed. They ignored the realities of modern air combat. So Romano began sketching a sight that did the opposite—one that compensated for movement automatically. Something that would let a gunner lead his target correctly every time.

What he was designing wasn’t just unauthorized. It was illegal. The Army Air Forces had strict regulations against modifying optical or mechanical sights in the field. Weapons were government property, and altering them was a court-martial offense. But Romano didn’t care. He wasn’t thinking about rules. He was thinking about survival—his, and that of the men around him.

And as he sat hunched over his notebook in the cold barracks at Bassingbourn, the engines of grounded bombers rumbling faintly outside, he began to draw the first lines of a design that would one day defy the engineers at Wright Field, the bureaucrats at Air Force command, and the very laws of military discipline.

It was the sight they said couldn’t work. The sight they said he wasn’t allowed to build.

But for Michael Romano—and for every man still flying into the black heart of Germany—it was the only thing that might keep them alive.

Continue below

October 14th, 1943. 5 miles above the Earth, deep inside the hostile airspace of the German Reich, Staff Sergeant Michael Romano is crouching inside a vibrating aluminum coffin. The tail section of his B17 Flying Fortress call sign knockout dropper is so cramped he cannot stand. He is perched on a narrow metal seat, little more than a bicycle saddle, his knees braced against the freezing fuselage.

Through the small warped plexiglass window, he watches a speck grow into a shark. A faka wolf 190. The German fighter banks lazily, then positions itself for an attack run. 6:00 low. The bomber’s single most vulnerable, most feared angle, the coffin corner. Romano squints, his breath fogging the inside of his oxygen mask.

His hands, clumsy and thick furlined gloves, wrestle the twin 50 caliber machine guns into position. He lines up his ring and bead sight. This is the aiming system the Army Air Force has provided. It is in reality two metal posts, a primitive tool from the 19th century, expected to work in a three-dimensional 500 mph battle.

It offers no compensation for speed, no calculation for deflection, no help whatsoever. He fires. A stream of tracers arcs harmlessly pathetically behind the diving fighter. The FW190s cannons flash. Bright, terrifying lights. 20 mm shells tear through the B17’s thin aluminum skin like tissue paper. Romano hears them. A brutal thump thump crunch. Walking up the fuselage, the entire 30ton aircraft shutters violently.

This exact scene is repeating itself 291 times today. This is the second Schwvine Fort raid. A mission so desperate, so infamous that its crews will forever call it Black Thursday. The mission was born from a dangerous idea, a belief, an arrogant myth. It was the core doctrine of the American bomber mafia, a group of generals who believed their new B17 flying fortress was exactly that, a fortress bristling with 1350 caliber machine guns.

They theorized it could fly deep into enemy territory in broad daylight without fighter escort and defend itself through sheer overwhelming firepower. They believed the bomber would always get through. On the morning of October 14th, the 8th Air Force dispatches 291 of these fortresses to strike the Schwvine ballbearing plants. This isn’t just a factory. It is the industrial heart of the Nazi war machine.

Destroy it and the German army grinds to a halt. There is just one fatal problem. To reach Schwinfort, the bombers must fly far beyond the range of their only protection. The P47 Thunderbolts, their little friends, can only take them as far as the German border. At 1:30 p.m. over the city of Aken, the fighter escorts waggle their wings and peel away. Their fuel is low.

They must return to England for the next 3 hours. The 291 bombers are utterly completely alone and the Luftvafa is waiting. The Germans have gathered more than 700 fighters, Messor Schmidt 109s, Fauler Wolf 190s, even twin engine Messersmidt 110 destroyers armed with rockets.

It is the single largest defensive patrol ever assembled. They don’t just attack the bomber stream. They swarm it. The air explodes. Jart B17s, each carrying 10 men, blossom into fireballs. Wings shear off. Fuselages spiral down, trailing black smoke for 5 miles to the earth. Men bail out into the flack fil sky, their parachutes ripped to shreds or engulfed in the flames of their neighboring aircraft.

The radio channels are a screaming chaos of mayday, mayday, we’re hit, and fighters on the tail. And then silence. By nightfall, the survivors limp back to England. The mathematics are not just brutal, they are unsustainable. 60 bombers, more than 20% of the entire attacking force, are shot down. Another 138 aircraft returned to base so badly damaged, so riddled with holes and cannon shells, they will never fly again.

600 American airmen are dead or missing in a single afternoon. At this rate, no bomber crew will statistically survive their required 25 mission tour. The eighth air force has been in effect broken. Post mission analysis at 8th Air Force headquarters in Haywam reveals the grim truth.

Tail gunners, supposedly the bomber’s last line of defense against the Luftwafa’s preferred attack angle, are achieving hit rates below 8%. Fighter pilots need merely attack from the rear, endure a few seconds of wildly inaccurate return fire, and methodically destroy America’s billiondoll strategic bombing campaign. One fortress at a time, senior commanders gather in despair.

The defensive armament supposed to make the B7 a flying fortress has failed catastrophically. Without a solution, daylight precision bombing, the entire strategic doctrine of the American war effort, faces cancellation. What these generals don’t know is that at that very moment, on a cold, windswept hard at Bassingborn airfield, a 22-year-old tail gunner with barely a high school education is sketching a design in his log book.

Tibui design that violates multiple Army Air Force regulations. A design that will be called mechanically impossible by trained weapons. Engineers. A design that will triple tail gun accuracy and save thousands of American lives. This is the story of the innovation they tried to ban and the gunner who refused to stop.

To understand why Romano’s innovation proved so revolutionary, you must first understand the impossible problem tail gunners faced in 1943. The B17 Flying Fortress entered combat with a defensive philosophy borrowed from naval warfare. The idea was simple. Bristle the aircraft with enough machine guns to create overlapping fields of fire, just like a battleship.

Army Air Force promotional materials boasted it was a flying battleship. Reality proved brutally different. Staff Sergeant Michael Romano reports to Bassingorn Airfield, England in August 1943. He’s a replacement tail gunner for the legendary 91st Bomb Group. He isn’t an engineer. He isn’t a scientist. He’s a former factory worker from Pittsburgh. No college degree.

barely 19 years old when he enlisted. The army trained him for six weeks on how to clear jams, estimate range, and pray his shots connected. His assigned position, the tail gunner station, is universally described by the men who occupied it as a coffin. It’s the most isolated, most terrifying position on the aircraft.

He must kneel for 8 hours at a time, feet braced against the aircraft structure, hands wrestling two 84-lb Browning M2 machine guns. The gun’s pivot on a simple yoke mount. But his aiming system, that was the real problem. The ring and bead sight was a relic, a metal circle with a post at the front.

To hit a diving fighter, Romano must in a split second estimate the target speed relative to his own aircraft. He must calculate the deflection angle, where to aim ahead of the target. He must compensate for bullet drop over hundreds of yards. He must execute all these complex trigonometric calculations while wearing bulky gloves, breathing thin oxygen in minus40° temperatures, all while another human being is actively trying to kill him. It was quite simply impossible.

Expert gunners firing from stationary aircraft at towed targets in the calm skies of Texas achieved hit rates that barely exceeded 12%. In combat, stressed, oxygen deprived, and under fire, actual hit rates plummeted to between 6 and 8%. The Luftwafa recognized this vulnerability immediately. German fighter tactics evolved throughout 1943 to exploit it.

They perfected the seexer angri, the 6:00 level or low attack. German pilots were instructed to accept 15 to 20 seconds of inaccurate tail gun fire close to 200 yards and then unleash devastating 20 mm cannon strikes. Luftwafa afteraction reports began to describe the B17 tail position as marginally dangerous its accuracy insufficient to deter attacks. The proof was in the casualty lists.

August 17th, 1943. The first Schwvine Fort raid, 60 bombers lost. October 8th, 1943. The Bremen raid, 30 bombers lost. October 10th, 1943. The Müster raid, 30 bombers lost. And now, Black Thursday, 60 more. The Eighth Air Force is hemorrhaging bombers and more importantly trained crews faster than factories in America can replace them.

General Henry Hap Arnold, the commanding general of the entire Army Air Forces, receives the casualty reports in Washington. He is horrified. He questions whether daylight bombing can or should continue. Engineers at Right Field propose solutions. More guns, bigger caliber guns, powered turrets. Boeing’s Cheyenne Modification Center begins designing an improved tail turret, but the development timeline stretches deep into 1944.

Prototypes for powered turrets exist, but installing them requires removing the entire tail section of the bomber. It’s a monthsl long factory modification impossible to implement on the hundreds of bombers already fighting and dying in England. Meanwhile, men die.

Michael Romano flies his first combat mission on August 19th, 1943 to Gilarion Airfield in the Netherlands. He fires 480 rounds at three, attacking Faka Wolf 190s. He thinks, he prays, he scored hits. But when the gun camera footage is reviewed later, the truth is laid bare. Every single tracer passed harmlessly behind the targets.

The fighters he was shooting at destroyed two bombers in his formation. After his third mission, Romano stays on the hard stand long after the rest of his crew has gone to debriefing. He just stares at his guns. His hands shake, not from fear, but from the sheer physical exhaustion of manh handling 84-lb weapons through sustained fire while kneeling at 25,000 ft.

That night, in his nice hut, he sketches his first design concept. The problem isn’t the gun. He realizes the Browning M2 is one of the finest weapons ever made. It’s not even the mount. It’s the tail gunners are firing blind. They are chasing targets they cannot properly track. Aiming at points in space they cannot accurately predict.

What Romano needs is something the Army Air Forces hasn’t provided. A way to see where his bullets will actually go. Before he pulls the trigger, he needs a reflector sight. The kind fighter pilots use a device that projects an illuminated aiming reticle onto a piece of glass, allowing for point and shoot accuracy. But the tail positions, cramped quarters, the tiny window, the violent vibration, it all makes a standard reflector installation impossible.

unless someone is willing to break the rules. Staff Sergeant Michael Romano possesses exactly zero qualifications for weapons engineering. He was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1924. He dropped out of high school at 16 to work in the steel mills when his father fell ill. He operated blast furnaces.

He repaired machinery. He learned practical metallurgy through trial and error, not from textbooks. When America enters the war, he enlists, hoping to escape the grueling factory work. The military assigns him to aerial gunnery school, not because of any demonstrated aptitude, but because he’s small.

At 5’7 and 145 lb, Romano can squeeze into the tiny spaces that eliminate larger recruits. He completes basic gunnery training at Harlingan Texas, scoring merely average on range qualifications. His instructors note his adequate trigger discipline and satisfactory weapons maintenance. Nobody nobody identifies him as exceptional.

He receives his silver gunner’s wings and is shipped to England, an interchangeable part in the vast grinding machinery of the Eighth Air Force. But Romano possesses one trait his training record doesn’t capture. He cannot accept systems that don’t work, especially when those systems are getting his friends killed. After his fifth combat mission on October 4th, 1943 to Frankfurt, Romano’s frustration reaches a critical mass.

His bomber, Knockout Dropper, returns to base with 78 flag holes and severe damage from two separate fighter attacks. Romano fired 620 rounds. He hit nothing. His best friend, the tail gunner on a neighboring B17, died when a Messor Schmidt BF109 attacked from dead a stern, and Romano’s counterfire failed to deter it.

That night, Romano walks to the aircraft revetment. He carries a maintenance flashlight and his log book. He climbs into the tail section of his bomber, the cramped space still wreaking of cordite and hydraulic fluid, and he just stares. He stares at the ring and bead sight that failed him. That failed his friend. The moment of insight arrives, not as a dramatic revelation, but as a simple, practical observation.

Romano notices his own reflection in the curved plexiglass window. In that distorted mirror, he can see behind his aircraft’s tail. He can see angles the primitive ring and bead sight can never cover. He begins to sketch rapidly, frantically. What if he mounted small mirrors at strategic angles? Mirrors that would give him peripheral vision.

Vision beyond the gun sight’s limited field of view. What if he angled them to show the tracer paths from his own guns? This would let him walk his fire onto a target by watching the reflection rather than squinting through inadequate iron sights and then the crucial leap.

What if he combined those mirrors with a simple reflector site, a piece of glass etched with an aiming reticle positioned to let him track a target while simultaneously watching his tracer patterns in the peripheral mirrors. It’s not a true computing gun site like the sophisticated gyroscopic systems in Allied fighters.

It’s a juryririgged improvised combination of reflective surfaces and aiming references. But it might just work. Romano spends 3 hours that night sketching designs, measuring angles, calculating sight lines with a carpenter’s protractor he salvaged from the base machine shop. By dawn, he has detailed drawings of a mirrorass assisted reflector sight system.

A system that requires no powered components, no complex installation, and no factory modification. He also has a very serious problem. His design, his idea is illegal. It violates Army Air Force technical order ZO120EG2, a regulation that explicitly prohibits unauthorized modifications to defensive armament. Installation without approval could and should result in a court marshal.

Romano looks at his drawings. He thinks about his friend. He decides he doesn’t care. A 22-year-old sergeant armed with a high school education and a log book full of forbidden sketches cannot build a new weapon system alone. He needs a co-conspirator. He finds one in the most unlikely of places, the base sheet metal shop.

Technical Sergeant Frank Kellerman was in many ways Romano’s opposite. At 38, he was a career non-commissioned officer, a hardened veteran of the Great Depression. He was a man who understood machinery, not from textbooks, but from a lifetime of fixing the unfixable. He’d served in the Civilian Conservation Corps, building bridges and repairing equipment with nothing but scrap iron and raw ingenuity.

Kellerman was a master scanger, a pragmatist, and he held a quiet contempt for officers who valued regulations over results. On October 7th, 1943, Romano approaches Kellerman’s bench. He carries his log book. He’s terrified. He’s not afraid of Kellerman, but of the words he’s about to say. He lays the drawings on the workbench.

Kellerman, wiping grease from his hands, studies the sketches for less than 5 minutes. He traces the lines for the mirror brackets, the mount for the reflector sight. He doesn’t say a word. Finally, he looks up, his face flat and unreadable. This is illegal, Sergeant. Romano’s heart sinks. He nods. Yes, Sergeant.

You’re asking me to perform an unauthorized modification to primary defensive armament. You’re asking me to violate about six different technical orders. You know that, right? Yes, Sergeant. Kellerman looks past Romano out the hanger door toward the flight line where the ground crews are already patching the holes on the bombers that returned from Frankfurt. He looks back at the drawings.

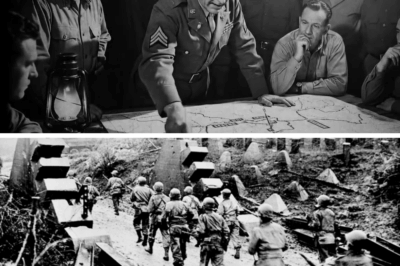

When do you fly again? Tomorrow, Sergeant. The target is Müster. Kellerman nods once. Then we’d better work fast. What follows is an act of industrial sabotage conducted by two loyal American soldiers. They begin after midnight in a dark, cold corner of the main maintenance hanger long after the senior officers have gone to bed.

They work using materials Kellerman has unofficially requisitioned over the past several weeks. This is a black market of survival. The base components come from salvaged aircraft parts. The curved convex mirrors are scavenged from the damaged navigation equipment of a B17 that crash landed the week before. The plexiglass sheets are cut from shattered canopy sections.

The aluminum brackets are fabricated from a writtenoff airframe. But the crucial component Trent, the heart of the entire system is the reflector site. Kellerman knows exactly where to get one. He leads Romano to the boneyard, a muddy field behind the hangers where wrecked aircraft are cannibalized for parts.

He climbs onto the wing of a P47 Thunderbolt fighter that had belly landed and was destined for the scrap heap. From the cockpit, Kellerman carefully removes the undamaged N3A reflector gun site. This is the device that gives fighter pilots their deadly accuracy. It’s designed for a roomy cockpit for nose-mounted installation. It was never intended to be crammed into the tail of a B17.

Back in the hangar, Kellerman re-engineers the mounting brackets on the fly. He and Romano work through the night, fitting components, testing sight lines, making minute adjustments with hand tools. At or 4:30 hours, just two hours before pre-flight briefing, Kellerman installs the complete assembly in Romano’s aircraft knockout dropper.

The installation is crude. It’s rough. The brackets are attached with standard aircraft bolts, not hightensil strength aviation hardware. The mirrors are affixed using safety wire. The reflector sight itself is mounted to the gun yolk via a welded bracket that would horrify a Boeing engineer.

Nothing about the modification appears in the aircraft’s maintenance log book. At the dawn briefing, Romano tells no one. His pilot, Lieutenant James Hullbrook, trusts his crew and doesn’t inspect the tail section before takeoff. The group commander doesn’t know. The squadron armament officer definitely doesn’t know. They launch for Müster at 0730 hours.

Over Germany at 10:15 hours, the Luftvafa rises to meet them. A Messer Schmidt BF 109 begins its attack run. The classic profile. 6:00 low. Closing fast. Romano swivels his heavy guns. He flips a small hidden switch Kellerman installed. and the world changes. He squints, but this time not through a tiny metal ring. He looks through a clear piece of glass.

And on that glass, an illuminated orange reticle floats in his field of vision, perfectly overlaying the distant target. In his peripheral vision, the three small mirrors Kellerman installed are reflecting the morning sun. They show him his own gun barrels. They give him instantaneous feedback about where his weapons are pointing before he even fires. He presses the trigger. A 3-second burst.

The tracer pattern visible in the mirrors shows him he’s shooting just behind the target. It’s the same mistake he always made, but now he can see it. He doesn’t guess. He adjusts. He leads the fighter by the reticle’s diameter. He walks the stream of tracers using the mirrors until the orange aiming dot and the stream of 50 caliber bullets converge on the 109’s engine. He fires again. The BF109’s engine cowling explodes.

It simply disintegrates. The fighter rolls inverted, completely out of control, and spins toward the Earth, trailing a thick, greasy column of black smoke. Romano stares at his guns, then at the mirrors, then back at the empty patch of sky where the fighter flew just seconds before. Holy, he whispers into his oxygen. Mask, it works.

Romano lands at Bassingborn at 1340 hours with one confirmed kill, his first. The celebration lasts exactly 20 minutes. At 1,400 hours, during a routine post-flight inspection, Crew Chief Master Sergeant Donald Pierce is checking the tail section for battle damage when he sees it. The welded bracket, the strange mirrors, the unauthorized wires running from the gun site.

Pierce, a by the booksman, immediately reports the discrepancy to the squadron armament officer. Captain Richard Voss arrives at the hardstand 10 minutes later. He carries a clipboard and an expression of barely contained fury. Voss is an engineer, a man who believes in protocols, testing, and regulations.

He sees the world in black and white, and what he sees in Romano’s tail position is a flagrant, dangerous violation. Sergeant Romano, Voss says, his voice tight with military precision. Would you care to explain the unauthorized equipment installed in your gun position? Romano snaps to attention. Sir, I installed an improved sighting system.

You installed what? Voss’s voice rises, drawing the attention of other ground crews. Do you have any comprehension of the regulations you just violated? Technical Order 0120 EG2 explicitly prohibits unauthorized modifications to defensive armament. He jabs a finger toward the tail section. This isn’t a hot rod in your backyard, Sergeant. This is a combat aircraft.

Unapproved modifications can compromise structural integrity. They can create fire hazards. They can interfere with other systems. Sir, Romano says, his voice shaking. The system works. I shot down a 109. I don’t care if you shot down the entire Luftwafa. Boss shouts. That equipment is not Army Air Force standard. It is not Boeing approved.

It has not undergone testing protocols. You will remove it immediately. Romano’s pilot, Lieutenant Hullbrook, steps forward. Captain with respect. My tail gunner got his first kill today using that sight. Maybe we should. Your opinion is noted, Lieutenant. Voss cuts him off, not even looking at him. The modification will be removed. That is final.

He glares at Romano. Consider yourself lucky I’m not having you brought up on charges for destruction of government property. Now get that junk off my aircraft. But the confrontation has drawn a crowd, and word is already spreading. Word spreads through the 91st bomb group like wildfire.

By evening mess, every gunner on the base, and half the pilots knows about Romano’s illegal mirror sight, and they know he got his first kill with it. The base divides. Opinions split sharply down the lines of rank. The veteran gunners, the men who have to fly the missions, gather around Romano’s table, firing questions.

How difficult is the installation? What’s the field of view? Can the mirrors withstand the vibration at 20,000 ft? They see a lifeline, but the engineering officers and senior maintenance staff, they react with alarm. This isn’t innovation. It’s a breakdown of discipline. Captain Theodore Morrison, the group’s assistant armament officer and Captain Voss’s superior, convenes an emergency meeting on the night of October 11th.

14 officers attend. The tone is hostile. Gentlemen, Morrison begins. We have a serious discipline problem. A sergeant, an enlisted man, has performed unauthorized modifications on a primary weapon system using salvaged components of unknown provenence. This sets a dangerous precedent.

What happens next? Do we let navigators rewire their radios? Do we let pilots adjust their own engine fuel mixtures? If every enlisted man decides to re-engineer his weapon system based on personal preference, we’ll have chaos. The room erupts. With respect, sir. That’s absurd. Major William Calhoun, the 91st’s operations officer, stands up. Calhoun is a combat man, a pilot who has seen his own crews shot down.

Romano shot down an enemy fighter using this system. Our tail gunners currently achieve what? An 8% hit rate. If this modification improves that, even marginally. Marginally. Morrison’s face reens. Major, we have no data. We have no testing. One lucky shot, one successful engagement doesn’t validate an unapproved juryrigged. Then test it. Calhoun fires back. Don’t remove it. Test it. Put Romano up on the next mission tomorrow.

Have him fly with the modification installed. Gun cameras will capture objective data. If it doesn’t work, I’ll remove it myself. But if it does work, maybe we should be installing these systems instead of court marshalling the man who invented them. The argument intensifies. Engineers cite safety concerns and slippery slopes.

Combat officers cite casualty rates and the grim unsustainable mathematics of Black Thursday. The meeting devolves into shouting. At 2,000 hours, the dispute, now too loud and too bitter to be solved at the squadron level, reaches the top.

It reaches the desk of Colonel Stanley Ray, the commanding officer of the entire 91st Bomb Group. Colonel Ray is 53 years old. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War. He is a career officer, a man who understands and respects the chain of command. But he is also a pragmatist, a man who has been signing letters to the mothers and wives of his dead airmen for months.

He summons Morrison, Calhoun, and Sergeant Romano to his office. He listens to the arguments from both sides for 90 minutes. Without interrupting once, he listens to Captain Morrison detail the regulations, the dangers, the breach of discipline. He listens to Major Calhoun detail the casualty rates, the failed tactics, the desperate need for any solution. Finally, he speaks.

His voice is quiet, but it cuts through the tension like a knife. How many bombers did we lose last week? Silence fills the room. Captain Morrison, Ry says, his voice flat. I asked you a question. 17, sir, from this group alone. 17, Ry repeats. 17 B7s. That’s 170 men. And how many fighters did our tail gunners shoot down during those same missions? Confirmed kills.

Morrison shifts. Three, sir. Ray nods slowly, letting the numbers hang in the air. 17 of our bombers against three of their fighters. He looks directly at Morrison, his eyes cold. Captain, your concern about unauthorized modifications is noted.

Your concern about regulations is valid, but I am far more concerned about losing 17 godamn airplanes every week because our defensive armament doesn’t work. He turns to Romano, who is standing at rigid attention. Sergeant, your modification stays on your aircraft. Captain Morrison’s face is pale. Sir, I must protest. The regulations the regulations are noted, Captain. Colonel Ray cuts him off.

He turns back to Romano. You will fly the next three combat missions with your modification installed. You will also fly with gun cameras recording every single engagement. If your hit rate improves measurably, as Major Calhoun suggests, we will authorize this mirror site for installation across the group.

If it doesn’t or if it fails, we’ll remove the equipment and you will face disciplinary action for the unauthorized modification. Is that understood? Romano’s knees are shaking, but he finds his voice. Yes, sir. Good. Ray stands, signaling the meeting is over. Gentlemen, this is adjourned. He pauses, looking at his engineering officer. And Captain Morrison, get me a set of those damned mirror drawings.

If this thing works, I want to know how. The test begins the very next day, October 12th, 1943. The target is Bremen. Romano flies his fourth combat mission with the modified sight system. The gun cameras are woring, recording every moment. The Eighth Air Force dispatches 236 bombers. The Luftwaffa scrambles 250 interceptors.

At 11:23 hours over the German coast, the attacks begin. A Foca Wolf 190 dives from 7:00 high. Romano tracks it through the reflector site. The illuminated reticle provides an instantaneous aim point. His peripheral vision, thanks to the mirrors, captures his own gun alignment. He fires a 4-se secondond burst, adjusting in real time as the tracer reflections show him his bullet path.

The FW190’s wing route erupts in flames. The fighter breaks off, trailing smoke. At 11:47 hours, a BF 109 approaches from 6:00 level. The classic deadly tail attack. Romano centers the reticle, checks his mirror feedback, and fires. The 109’s canopy shatters. The fighter rolls inverted and dives straight down.

The gun camera footage captures both engagements in crystal clear. Undeniable detail. Romano returns to Bassingorn with two confirmed kills and one probable. His total ammunition expenditure for the mission, 380 rounds. The engineering staff reviews the footage that night in stunned silence.

Captain Morrison watches Romano’s tracer patterns visible in the mirror’s reflection walk directly onto the targets. Even he cannot dispute the evidence. The mirror reflector combination allows for realtime fire correction that was simply impossible with the old ring and bead sights. The numbers are analyzed.

The average tail gunner in the 91st bomb group fired 2,800 rounds for every one confirmed kill. On his first test, Michael Romano fired 190 rounds per kill. It’s not just an improvement. It’s a revolution. All right, Morrison admits quietly to Colonel Ray. It works, but sir, we need proper engineering drawings, standardized components, installation procedures.

We can’t just weld scrap metal to the bombers. How long to get it approved? Colonel Ray asks Morrison’s size. 6 weeks minimum. We’d have to coordinate with ETH Air Force headquarters, submit modification proposals, get approval from the States. We don’t have 6 weeks, Ray snaps. We’re losing the war now. He turns to technical sergeant Frank Kellerman, the man who had helped build the prototype.

Sergeant, how many of these systems can you build per day using the materials you have on this base? Kellerman, the master scramger, considers. With help from the sheet metal shop, if we scavenge reflector sights from the boneyard, maybe four complete assemblies per day, sir. Then start building, Ray commands. I want every tail gunner in this group equipped within two weeks.

Morrison objects. Sir, without proper authorization from Eighth Air Force. Captain, Ray says, his voice final. I will handle ETH Air Force. You handle the engineering specifications. Get it done. Dismissed. What follows is an improvised manufacturing operation that would horrify military procurement bureaucrats.

It is a monument to enlisted man ingenuity. Kellerman and his maintenance team become a covert production line. They scavenge components from across Bassingborne. Reflector sights from writtenoff P47s and P38s. Mirrors from damaged navigation equipment. Aluminum stock from supply warehouses. They establish an assembly line in the corner of the maintenance hanger, fabricating by hand four complete mirror sight systems per day.

As each bomber lands from a mission, its tail guns are stripped of a the ring and bead sight and the Romano Kellerman modification is bolted into place. By October 20th, 18 B17s in the 91st bomb group carry the illegal modification. The results are immediate and dramatic. October 20th, on a mission to Duran, tail gunners equipped with the new mirror sights achieve 11 confirmed kills against 47 fighter attacks.

That’s a 23.4% hit rate, nearly triple the previous average. November 3rd, Wilhelm Hav 16 confirmed kills. Hit rate 23.5%. November 5th, Yelson Kirkin 13 confirmed kills. Hit rate 21.8%. The mathematical impact transforms bomber survivability. Luftwafa pilots accustomed to attacking B17s from the rear with relative impunity are suddenly dying. They are facing accurate sustained and deadly defensive fire.

The proof comes not just from Allied gun cameras but from the enemy. German afteraction reports begin to note with alarm the increased effectiveness of American tail weapons. They recommend revising approach tactics. Major Hans Yawakam Yabs, a Luftvafa fighter ace writes in his combat diary, “The flying fortresses have become significantly more dangerous.

Their tail gunners now demonstrate accuracy previously seen only in power turrets. Attacks from the rear quadrant now carry unacceptable risk. The word and the data. Finally reach 8th Air Force headquarters at High WOME. On November 18th, a staff car pulls up unannounced at Bassingborn. Outsteps Brigadier General Frederick Castle, commander of the fourth bombardment wing. He’s not there to court marshall anyone.

He’s there to see the miracle for himself. He inspects Romano’s tail position personally. He examines the crude brackets, the salvaged mirrors. He reviews the gun camera footage. He interviews Sergeant Romano for 30 minutes. Sergeant General Castle asks, “How did you know this would work?” Romano, still a 22-year-old sergeant, just shrugs. “I didn’t, sir, but the old sights definitely didn’t work.

So, I figured anything else might be an improvement. Castle laughs. The first time anyone at headquarters has laughed about tail gunnery in months. Fair point, he says. He studies the mirror assembly. This can be manufactured at the depot level. Yes, sir. Romano says, Sergeant Kellerman has the drawings, General Castle nods.

I’m authorizing immediate implementation across the entire fourth wing. Every B7 will receive this modification within 30 days. He looks directly at Romano. Sergeant, you probably saved more American lives today than you will ever know. By December 1943, Romano’s mirror reflector sight system, now officially designated the field expedient tail gun aiming system type 1, is installed in over 200 B7s.

Boeing’s Cheyenne Modification Center, which was already developing an improved tail turret, gets wind of Romano’s field fix. They incorporate his core principles, the reflector site, the improved visibility into their design. The production Cheyenne tail turret, which begins appearing on brand new B17Gs in January 1944, features an N8 reflector site positioned almost exactly where Romano’s salvaged P47 site sat in his improvised installation.

The illegal modification had become standard equipment. The impact on bomber crew survival rates is measurable and significant for B7 groups. Equipped with the improved tail sights, losses from tail attacks decrease by approximately 35% between late 1943 and March 1944. That percentage translates to dozens of bombers and hundreds of lives.

Saved by a modification one engineering captain initially called illegal and dangerous. Michael Romano continues flying combat missions through February 1944. His personal tally reaches seven confirmed kills and four probables. Exceptional for a tail gunner. But on February 22nd during the big week offensive, his bomber takes heavy flack damage over Leipig.

He continues engaging fighters even as hydraulic fluid and fuel spray through his tail section. His aircraft knockout dropper crash lands in Belgium. The crew survives, but Romano spends the final months of the war in a German P camp. He returns to the United States in May 1945, weighing just 127 pounds. The army air forces awards him the distinguished flying cross for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Hy the citation notes his innovative contribution to defensive armament effectiveness. It carefully avoids mentioning that his innovation was at first illegal. Romano never seeks publicity. He declines interview requests from military journals. When Boeing engineers invite him to their Seattle facility to discuss the Cheyenne turrets development, he politely refuses.

He says, “I just made what I needed to survive. Other people turned it into something official.” He returns to Pittsburgh, marries his high school sweetheart, and works as a machinist for 37 years. He rarely if ever discusses the war, but the legacy of his improvised mirror reflector system extends far beyond his personal modesty. Postwar analysis by the US strategic bombing survey quantified the staggering impact.

B17 groups equipped with improved tail gun sights, sites born from Romano’s design, suffered 32 to 37% fewer tail attack losses across thousands of bomber missions. That percentage represents approximately 840 aircraft and 8400 crewmen who survived combat. They statistically should not have 8,400 lives. In 1983, the 91st Bomb Group Association holds a reunion at the old Bassingborn airfield.

Several gay-haired tail gunners who flew with Romano’s mirror reflector sits attend. One of them, a man named Gerald Hammond, brings a salvaged mirror bracket he has kept for 40 years. He stands before Romano, now 60 years old, and says simply, “Because of you and those mirrors, I came home. My kids exist because you couldn’t accept lousy gun sights. Thank you.

” Romano, uncomfortable with the emotion, just shrugs and replies, “You would have done the same thing. We all just wanted to survive long enough to go home.” But that’s where Romano was wrong. Thousands of tail gunners face the same inadequate sights. Thousands face the same impossible firing solutions and the same terrible casualty rates.

Only one of them refused to accept the status quo. Only one of them had the audacity to break regulations, the skill to improvise a solution, and the courage to risk a court marshal for the chance to save lives. Michael Romano died in 2003 at the age of 79.

His obituary in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette mentions his military service in a single line. World War II veteran, Eighth Air Force. It doesn’t mention that he saved thousands of lives with mirrors and salvaged aircraft parts. It doesn’t mention that his illegal modification became standard equipment for an entire air force. It doesn’t mention that while generals and engineers debated regulations and testing protocols, a 22-year-old factory worker from Pittsburgh solved a problem they couldn’t. Because the best innovations don’t come from a committee.

They don’t come from asking for permission. They come from people who refuse to watch others die while waiting for approval.

News

CH2 Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies

Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies The morning air over the Solomon Islands carried…

CH2 Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart

Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart Bismarck Sea, March 3rd, 1943. At precisely 0600 hours,…

CH2 Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting In…

CH2 How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter

How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter The De Havilland Mosquito shouldn’t have worked….

CH2 When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible

When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible At dawn on February 20th, 1943,…

End of content

No more pages to load