How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks

May 7th, 1943. Dawn light seeped through the canvas walls of a maintenance tent on Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field, casting long, pale streaks across the dirt floor. Private James Red Harmon knelt over a frayed length of Manila hemp, threading it carefully through his calloused hands. The rope had once held hay bales on his father’s Nebraska farm, and in that moment, it felt heavier with purpose. Around him, the aviation mechanics snorted and chuckled. Red’s suggestion—so simple, so absurd—had already been dismissed with the kind of patronizing amusement reserved for farm boys who hadn’t yet learned the language of modern warfare.

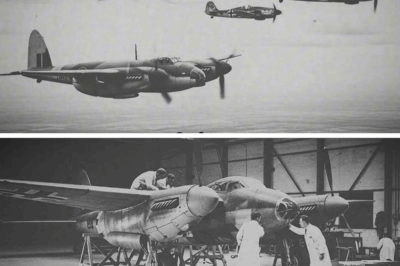

Aircraft armament systems, they explained again, required precision engineering. Hydraulic timing mechanisms, electrical firing circuits, and synchronized gear systems ensured bullets didn’t strike propeller blades and that every component operated within tolerances too tight for improvisation. A rope, they insisted, belonged in the agricultural past, not the cockpit of a P-38 Lightning fighter. But Red Harmon had grown up solving problems with whatever materials were at hand. For three weeks, he had watched American pilots return from combat missions with aircraft riddled with bullet holes and cannon impacts, each story defying the predictions of training manuals.

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Japan’s premier fighter, had been portrayed in doctrine briefings as light, fragile, and easily outclassed by U.S. designs. Structural weakness, the intelligence officers claimed, made it a sitting target. Yet pilots who survived engagements with Zeros described a machine that outturned, outclimbed, and outmaneuvered every fighter the Americans had deployed to the Pacific. The contradiction between doctrine and reality had cost American lives at an unsustainable rate in the opening months of the campaign. Henderson Field’s maintenance crews spent their days repairing damage that should have been inconceivable, aircraft returning riddled with 20 mm cannon fire, some barely airworthy, and some never returning at all.

The strategic situation had become desperate enough that squadron commanders were soliciting ideas from anyone, regardless of rank—a stark departure from normal military protocol. Red Harmon’s rope trick, though unpolished, emerged from careful observation and practical ingenuity rather than formal engineering. He had noticed a consistent pattern among pilots who survived Zero encounters. Japanese aviators would maneuver into firing position, align for a deflection shot, and pause briefly to confirm their sights before committing to sustained fire. That half-second pause, minuscule to a human observer, was the only window for a U.S. pilot to react.

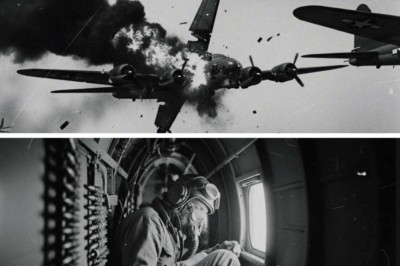

Theoretically, that pause was sufficient. In practice, human reaction time was measured in fractions of seconds, and every fraction counted. By the time a pilot recognized visual or auditory cues, processed them in the brain, and transmitted corrective movements to the hands and feet, enemy rounds had already struck the aircraft. The math was brutal. A Zero’s armament—two 20 mm cannons and two 7.7 mm machine guns—delivered projectiles at velocities approaching 2,000 feet per second. An American pilot needing even three-quarters of a second to respond often found the first rounds puncturing fuel tanks, control surfaces, and fuselage before evasive maneuvers could take effect.

Red’s solution bypassed conscious thought entirely. A mechanical system that reacted to external stimuli faster than any pilot could process it became his focus. The idea was agricultural in origin, deceptively simple. On the farm, tension-release mechanisms had secured loads for generations. Rope under strain would contract with force proportional to its elasticity and the weight it restrained, operating independently of human intervention. The principle, though centuries old, had never been applied to aviation.

Adapting the concept to a fighter plane posed a formidable challenge. Aircraft environments were brutal: vibrations, temperature extremes, and G-forces that would shred ordinary rope within hours. Manila hemp, sturdy on a barn floor, might snap under combat stress, and yet the fundamental principle—mechanical, immediate, unavoidable—remained sound. Red spent days experimenting with different rope types, measuring tensile strength, elasticity, and the durability of knots under conditions simulating high-speed maneuvers. He stretched cords over blocks, looped them through pulleys, and twisted them around wooden dowels, observing every fray, every snap, every small deformation.

By the fourth day, he had developed a prototype. The rope was anchored to a trigger mechanism on the P-38’s wing-mounted guns, threaded through a series of tension points designed to release at the precise moment the pilot initiated forward throttle or slight evasive roll. It was crude, silent, and fully manual in installation, but it promised a way to ensure that firing could react more quickly than human reflexes allowed. Red called it “the stupid rope trick,” mostly in self-deprecating frustration at the incredulity of the mechanics around him.

The other men in the tent were skeptical, though a few began to watch quietly, curiosity gradually replacing derision. Chief Petty Officer Dunham, a grizzled veteran of the Pacific campaign, shook his head. “Son, you’re playing with luck, not science,” he muttered. But Red, who had learned from years on the farm that luck favored preparation and improvisation, ignored the caution. He wrapped the rope with extra layers of tape, twisted the release loops to minimize friction, and attached the contraption to the aircraft’s guns. Everything had to be tight, everything had to survive hundreds of pounds of pressure, violent maneuvers, and the unpredictable environment of combat.

Red’s mind drifted, as it often did, to the pilots he had watched limp back to Henderson Field over the past weeks. Men who should have dominated the skies were returning battered, shells embedded in fuselage and wings, some barely able to land. He remembered Lieutenant Harris, whose engine had been hit mid-turning engagement, spinning helplessly before managing to crash-land without injury. He remembered Sergeant Mills, who had fought off a Zero with a wing now perforated by twenty-five 20 mm shells, somehow keeping control just long enough to glide back to base. Red had repaired both planes and learned each time what worked—and what failed.

As dawn broke over Henderson Field, the first rays of sunlight reflected off the aluminum fuselage of the waiting fighters. The tent smelled of oil, sweat, and charred gunpowder from previous missions. Red held the rope in his hands again, appreciating the simplicity of it. He did not see the world in diagrams or engineering formulas; he saw problems and solutions. The Zero’s momentary pause could be exploited. The rope, correctly applied, could act faster than any pilot could, providing a mechanical advantage over death itself.

Testing the device in the controlled chaos of a maintenance tent was only the beginning. Red ran simulations on grounded aircraft, pulling ropes to verify triggers, measuring elasticity, and observing any unintended mechanical interactions. The rope had to withstand torque, vibration, and the sudden acceleration of gunfire without fraying or snapping. Each adjustment brought small victories: a smoother release here, a tighter knot there, until the system was consistent enough that he could finally smile at its potential.

Yet the human factor remained unpredictable. Pilots were trained to operate guns manually, to rely on reflex and instinct, and the military hierarchy had little patience for improvisation. Many in Red’s tent still laughed quietly at the farmhand’s antics, seeing them as charming but irrelevant. Red knew, however, that relevance would only become clear in the fire of combat. For now, the prototype rested across the floorboards of the P-38, a length of rope that might seem absurd but carried the weight of observation, ingenuity, and a desperate need to save lives.

Three weeks of trial, error, and silent tinkering had brought Red Harmon to this moment. The rope lay coiled in his hands, simple yet extraordinary, the product of a mind trained to solve problems with practical tools rather than theoretical equations. Outside, the morning sun illuminated the field, the sounds of engines warming and pilots briefing merging into a single, tense hum. Somewhere over the Pacific, a Zero would rise to meet American aircraft, and within that fleeting, dangerous encounter, the rope would act faster than any human could hope to respond.

Red’s thoughts drifted back to Nebraska, to the endless fields, the scent of hay, the rough texture of hemp under his fingers. Everything he had learned there—the patience, the observation, the understanding of tension and leverage—was distilled into this simple piece of rope. It was “stupid” in name only; its genius lay in its simplicity, a quiet defiance of assumptions and a practical answer to the deadly calculus of aerial combat.

And so, Henderson Field waited. Pilots would climb into cockpits, engines would roar, and the Pacific sky would erupt in motion and fire. Yet beneath it all, a single farmhand’s rope waited to act, faster than thought, faster than fear, and potentially, faster than death itself.

What happened next would change the course of engagements over Guadalcanal, proving that ingenuity, even when dismissed as foolish, could outmatch technology and doctrine. For now, however, the rope lay still, unassuming, a silent witness to the dawn of action that would unfold in the weeks to come.

Continue below

May 7th, 1943. Dawn light filtered through the canvas walls of a maintenance tent on Guadal Canal’s Henderson Field. Private James Red Harmon threaded a frayed length of Manila hemp through his calloused hands, the same rope that had once secured hay bales on his father’s Nebraska farm. The aviation mechanics around him had already dismissed his suggestion with the kind of laughter reserved for ideas too simple to work.

Aircraft arament systems, they explained with the patience afforded to farm boys who didn’t understand modern warfare required precision engineering. Hydraulic timing mechanisms, electrical firing circuits, synchronized gear systems that prevented bullets from striking propeller blades. These were the technologies that separated industrial warfare from frontier improvisation.

A rope, they assured him, belonged in the agricultural past he’d left behind, not in the cockpit of a P38 lightning fighter. But Red Harmon had grown up solving problems with whatever materials were available. and he’d spent the past three weeks watching American pilots return from combat with stories that didn’t match the confident predictions in training manuals.

The Mitsubishi A6M0, Japan’s premier fighter aircraft, was supposed to be inferior to American designs. Lighter construction, the intelligence briefings claimed, meant structural weakness. Yet pilots who survived encounters with zeros described an aircraft that could outturn turn, outclimb, and outmaneuver every fighter the United States had deployed to the Pacific theater.

If you’re enjoying this deep dive into the story, hit the subscribe button and let us know in the comments from where in the world you are watching from today. The contradiction between doctrine and reality had cost American lives at an unsustainable rate during the campaign’s opening months. Henderson Fields maintenance crews spent their days repairing bullet damage to aircraft that should have dominated enemy fighters, but instead returned riddled with 20 mm cannon fire, if they returned at all. The strategic situation had grown critical enough that squadron

commanders were soliciting suggestions from anyone, regardless of rank, a departure from military protocol that reflected genuine desperation rather than democratic ideals. Red’s rope trick, as it would come to be known, emerged from observation rather than formal engineering education. He’d noticed that pilots who survived zero encounters consistently described a specific tactical sequence.

Japanese pilots would maneuver into firing position, align their aircraft for a deflection shot, then hold their trigger briefly to confirm their gunsite alignment before committing to sustained fire. That momentary burst, lasting perhaps half a second, gave American pilots their only warning before a deadly concentration of cannon and machine gun fire tore through their aircraft’s vulnerable components.

The warning was theoretically sufficient for evasive action, but human reaction time operated on scales measured in fractions of seconds. By the time a pilot’s brain processed the visual or auditory cue of enemy fire, transmitted the appropriate commands to his hands and feet, and initiated the control inputs necessary for evasive maneuvering.

Japanese rounds were already impacting his aircraft structure. The mathematical reality was unforgiving. Azer’s armament consisting of two 20 mm cannons and two 7.7 mm machine guns delivered projectiles at velocities approaching 2,000 ft pers. An American pilot requiring even 3/4 of a second to initiate evasive action would find enemy rounds striking his aircraft before his controls could respond to his inputs.

Red’s solution bypassed human reaction time entirely by introducing a mechanical system that responded to external stimuli faster than conscious thought could process them. The concept was agricultural in its simplicity. Tension release mechanisms had secured loads on farm equipment for generations, operating through principles that required no electrical power or complex machinery.

A rope under tension, when suddenly released, would contract with force proportional to its elastic properties and the load it had been restraining. Applied to aircraft armament, this same principle could trigger defensive systems without requiring pilot awareness or decision-making.

The technical challenge lay in adapting farm equipment concepts to combat aviation’s demanding operational environment. Aircraft experienced vibrations, temperature extremes, and G-forces that would destroy conventional rope systems within hours of installation. The hemp rope that secured hay bales on Red’s family farm would disintegrate under conditions that fighter aircraft routinely encountered during combat operations.

Yet, the fundamental concept remained sound if suitable materials and installation methods could be identified. Red spent three days experimenting with different rope types, testing their tensile strength, elasticity, and durability under conditions that approximated combat stress.

Manila hemp, traditionally used in maritime applications, offered the best combination of strength and flexibility. Its fiber structure provided resilience against repeated stress cycles while maintaining dimensional stability across temperature ranges from freezing to over 100° F. Most critically, its surface texture provided sufficient friction to maintain tension under vibration while allowing controlled release when trigger mechanisms activated.

The installation system RED developed utilized existing aircraft structure without requiring modifications that would compromise airframe integrity or add significant weight. The P38’s unique twin boom design provided mounting points that conventional single engine fighters could not offer, allowing rope systems to be rooted through the aircraft’s central nel where they would remain protected from prop wash and enemy fire.

Each rope connected to a spring-loaded release mechanism positioned adjacent to the aircraft’s ammunition feeds, creating a mechanical linkage between enemy fire impact and defensive response that operated independently of electrical systems. The triggering concept exploited the Zero’s tactical doctrine in ways that Japanese pilots would not anticipate until experiencing its effects firsthand.

When enemy rounds struck a P38’s fuselage, they transferred kinetic energy into the aircraft’s structure, creating vibrations that conventional design absorbed through flexible mounting systems. RED’s modification channeled these vibrations into mechanical triggers that detected impacts through differential motion between the rope’s fixed mounting points and its tensioned sections.

A single 20 mm round striking anywhere along the aircraft’s central fuselage would generate sufficient structural displacement to activate the release mechanism. The defensive system itself remained elegantly simple in conception, though demanding in execution. Upon detecting enemy fire through structural vibration, the rope system released a preloaded counterwe that rotated the aircraft’s control surfaces into an immediate banking turn.

The maneuver occurred faster than human reflexes could initiate it, presenting Japanese pilots with a target that began evasive action before they could follow up their initial burst with sustained fire. More importantly, the system’s purely mechanical nature meant it could not be jammed by radio interference or disabled by electrical damage that would incapacitate conventional defensive systems.

Squadron maintenance officers initially rejected RED’s proposal with reasoning that reflected institutional conservatism rather than technical analysis. Military aviation had evolved through decades of incremental refinement, creating doctrinal assumptions about what constituted acceptable engineering practice. Rope systems, regardless of their theoretical merit, represented a regression to technologies that the aviation industry had deliberately abandoned during its transition from fabric covered biplanes to all metal monoplane fighters. The suggestion that

agricultural materials could enhance combat effectiveness seemed to violate fundamental principles about technological progress and military professionalism. Captain Robert Westbrook, Henderson Fields senior maintenance officer, had spent 15 years in naval aviation before transferring to the Army Air Forces.

His career had been built on mastering complex electrical and hydraulic systems that represented the cutting edge of aeronautical engineering. The suggestion that a Nebraska farmhand had identified a solution that professional engineers had overlooked challenged not only his technical judgment but his understanding of how military innovation was supposed to function.

solutions came from research laboratories and engineering bureaus, not from enlisted personnel with agricultural backgrounds. Yet, Westbrook was also pragmatic enough to recognize that the Pacific theater demanded solutions regardless of their source or their conformity to institutional expectations.

American pilots were dying at rates that threatened to exhaust trained replacement pools before Japanese defensive capabilities could be degraded through attrition. The strategic calculus was brutal in its simplicity. Either American fighters achieved tactical par with the zero through some means or the entire Southwest Pacific campaign would stall for lack of air superiority.

If a farm boy’s rope trick offered even marginal improvement in pilot survival rates, it deserved testing regardless of how it challenged conventional engineering assumptions. The first test installation occurred on May 15th, 1943 using a warweary P38 that had already accumulated sufficient combat damage to justify experimental modifications.

Red and a team of skeptical mechanics spent two days rooting manila hemp through the aircraft’s structure, calibrating tension loads and adjusting trigger sensitivities through trial and error that recalled his farm experience more than formal engineering methodology. The installation added exactly 11 lb to the aircraft’s empty weight, a negligible increment that fell well within acceptable tolerances for operational loading.

Ground testing revealed immediate problems that formal engineering review might have anticipated, but practical experimentation identified more efficiently. The initial rope routing created friction points where the hemp araided against aluminum structure, generating heat that would have caused system failure within hours of sustained operation.

Red’s solution involved wrapping friction points with leather strips salvaged from damaged flight jackets, creating bearing surfaces that reduced wear while maintaining the systems mechanical integrity. The modification reflected problem-solving approaches common to agricultural equipment maintenance where available materials dictated solutions regardless of their conformity to engineering textbooks.

The trigger mechanism sensitivity required extensive calibration to distinguish between enemy fire impacts and the normal vibrations that aircraft experienced during high-speed maneuvering. Initial settings proved too sensitive, activating during routine flight operations and creating uncommanded control inputs that would have been more dangerous than the enemy fire they were supposed to counter.

Red adjusted the trigger thresholds through systematic testing, gradually increasing the activation force required until the system responded only to impacts consistent with 20 mm cannon strikes. The final calibration represented a compromise between reliability and responsiveness that would prove adequate for combat conditions if not optimal by formal engineering standards.

Flight testing began on May 22nd with Captain Thomas Maguire, a pilot whose combat experience and technical judgment made him the logical choice for evaluating unconventional defensive systems. Maguire had survived three encounters with zeros during the previous month. Experiences that left him skeptical of any solution that promised easy answers to tactical problems that had killed more experienced pilots than himself.

His pre-flight inspection of Red’s modification revealed craftsmanship that exceeded his expectations, though he remained unconvinced that agricultural rope could address challenges that aeronautical engineering had failed to solve. The test protocol called for simulated combat maneuvers without actual enemy contact, allowing Meuire to evaluate the systems response characteristics under controlled conditions before risking its performance against Japanese fighters.

The results exceeded even Red’s optimistic predictions. When ground crews fired blank cartridges against the fuselage to simulate enemy impacts, the rope system initiated banking turns within onetenth of a second, faster than Meuire could have reacted through conscious control inputs. The maneuvers were abrupt enough to be uncomfortable, but remained within glo limits that pilots regularly experienced during combat maneuvering.

More significantly, the systems response varied based on impact, location, and intensity, creating evasive patterns that appeared random from an external observer’s perspective. This unpredictability represented an unexpected tactical advantage as Japanese pilots trained to anticipate American evasive maneuvers would find themselves facing targets whose defensive reactions defied pattern recognition.

The rope’s mechanical properties introduced variability that electrical or hydraulic systems with their precise and repeatable responses could not duplicate without complex programming that 1943 technology could not provide. Maguire’s report recommended immediate installation on operational aircraft, though he cautioned that combat testing would be necessary to validate the systems effectiveness against actual enemy tactics.

His endorsement carried sufficient weight that Captain Westbrook authorized installation on six P38s from the 339th Fighter Squadron, enough aircraft to provide meaningful tactical assessment while limiting exposure if the system proved ineffective or dangerous during actual combat. The strategic context for RED’s innovation reflected broader patterns in Pacific theater operations during mid 1943.

American industrial production had begun delivering aircraft and equipment in quantities that Japanese manufacturing could not match. Yet numerical superiority provided limited advantage when individual Japanese aircraft demonstrated performance characteristics that American fighters struggled to counter. The Zero’s combination of extreme agility, long range, and experienced pilots created tactical situations where American numerical advantages often translated into higher absolute casualties despite favorable exchange ratios. Intelligence assessments of zero capabilities had

consistently underestimated the aircraft’s performance while overestimating its vulnerabilities. Early reports suggesting that the Zero’s light construction made it fragile proved incorrect when combat experience demonstrated that Japanese engineers had achieved structural efficiency rather than weakness.

The aircraft could sustain battle damage that would destroy heavier American fighters while maintaining flight control and combat effectiveness. Its armorament, though lighter than American standard, proved devastatingly effective when Japanese pilots exploited their aircraft’s superior maneuverability to achieve optimal firing positions.

The tactical doctrine that American pilots had learned during training proved inadequate against opponents who understood their own aircraft strengths while exploiting American fighters limitations. Training emphasized energy tactics using superior speed and dive performance to engage and disengage at will. But Zeros operated at altitudes and speeds where American advantages diminished, forcing combat into turning engagements where Japanese maneuverability proved decisive.

Pilots who survived their first encounters with zeros learned to avoid prolonged dog fights. But this defensive posture surrendered tactical initiative to an enemy who could choose when and where to engage. Red Harmon’s rope system offered a potential solution to one specific aspect of this tactical challenge.

While it could not improve American aircraft performance or pilot skill, it could reduce the window of vulnerability that existed between the moment Japanese pilots opened fire and the moment American pilots could initiate evasive action. That fraction of a second advantage might seem insignificant in isolation, but combat statistics suggested that most successful zero attacks achieved decisive damage during their initial firing pass.

If the rope system could disrupt that critical first burst, it might shift tactical odds sufficiently to affect overall engagement outcomes. The first combat test occurred on May 27th, 1943 during a fighter sweep over Japanese-h held positions on New Georgia. Captain Maguire led a flight of four P38s, three equipped with Red’s rope system and one flying as a control aircraft with standard configuration.

The mission profile called for medium alitude patrol over enemy shipping lanes, an assignment that historically produced contact with Japanese fighters operating from airfields on nearby islands. Contact came at 11,000 ft when a flight of 6 dove from cloud cover. Their attack coordinated with the precision that characterized experienced Japanese fighter units.

The fear engagement developed exactly as intelligence briefings had predicted and training had prepared pilots to counter. Maguire’s flight maintained formation while initiating a shallow dive to build speed for disengagement. Standard doctrine for P38s facing superior numbers of more maneuverable opponents.

The lead zero pilot selected Maguire’s wingman as his initial target, maneuvering into a high-side firing position that would allow deflection shooting against an opponent committed to maintaining formation with his flight leader. The tactical situation represented a dilemma that had killed countless American pilots throughout the campaign’s opening year.

Breaking formation to evade would leave other flight members vulnerable, while maintaining formation exposed the targeted aircraft to fire it could not effectively counter. The Zer’s opening burst caught Maguire’s wingman exactly where Japanese gunnery training predicted he would be. 20 mm rounds converging on the P38 central nel in a pattern designed to disable the aircraft’s engines and flight controls with a single pass.

But the impact that should have begun the aircraft’s destruction instead triggered Red’s rope system, initiating a violent banking turn that carried the P38 out of the Zero’s firing solution before sustained fire could follow the initial burst. The Japanese pilot’s surprise was evident in his subsequent maneuvering as he attempted to reacquire a target that had evaded through what appeared to be precognitive awareness of his attack.

His tactical training had not prepared him for opponents whose defensive reactions began before human perception should have allowed, creating a temporal advantage that contradicted everything Japanese doctrine assumed about American capabilities. His second attack approach proved more cautious, reflecting uncertainty about whether he faced a technological innovation or an exceptionally skilled opponent.

The engagement continued for 12 minutes as the Zero Flight attempted to isolate and destroy American aircraft that refused to behave according to established patterns. Each time Japanese pilots achieved firing position and initiated their characteristic warning burst, the rope equipped P38s would execute evasive maneuvers that disrupted aiming solutions before sustained fire could be applied.

The control aircraft, lacking Red’s modification, suffered multiple hits during the engagement, though its pilot’s skill and the inherent toughness of P38 construction allowed him to return to Henderson Field with significant battle damage. Maguire’s afteraction report documented results that exceeded the most optimistic predictions for Red’s system.

The three modified aircraft had avoided all significant damage despite numerous enemy firing passes, while the unmodified aircraft required extensive repair work that would keep it grounded for a week. More significantly, the rope system had disrupted Japanese tactical coordination by forcing enemy pilots to expend additional time and ammunition achieving firing solutions that should have succeeded on the first attempt.

The cumulative effect of these delays had prevented the Zeros from concentrating their attacks effectively, allowing the American flight to maintain cohesion while withdrawing from an engagement that would normally have resulted in at least one aircraft lost.

The tactical implications extended beyond simple survival statistics to fundamental questions about how defensive systems could alter combat dynamics. Japanese pilots who encountered rope equipped P38s found themselves facing opponents who seemed to predict their attacks with impossible accuracy, creating psychological pressure that affected subsequent tactical decisions.

The uncertainty about whether they faced technological countermeasures or superior pilot skill introduced hesitation into attack sequences that relied on aggressive, decisive action for success. Captain Westbrook’s technical analysis of the engagement focused on the rope systems mechanical performance under combat conditions. Post-flight inspection revealed that the hemp had absorbed battle damage without catastrophic failure.

Its fibrous structure distributing impact stress in ways that prevented single point failures. One aircraft had sustained a direct hit on the rope installation, severing approximately 30% of the hemp’s cross-section, yet the remaining fibers maintained sufficient strength to activate the trigger mechanism during a subsequent attack.

The redundancy was accidental rather than designed, but it demonstrated robustness that formal engineering might not have predicted. The ammunition expenditure data that Maguire’s flight recorded provided additional evidence of the systems tactical value. Japanese pilots had fired an estimated 800 rounds of 20 mm ammunition during the engagement, four times the normal expenditure for similar combat durations.

The increased consumption reflected the additional firing passes required to engage targets that evaded before sustained fire could be applied, forcing enemy pilots to repeat attack sequences that should have achieved decisive results on initial attempts. By early June 1943, installation requests for Red’s Rope system exceeded available manufacturing capacity.

Henderson Fields maintenance facilities could produce perhaps two complete installations per day, working with materials that had to be requisitioned through supply channels never designed to deliver agricultural rope to combat theaters. The demand reflected not only the systems combat effectiveness, but also the desperate tactical situation that American fighter units faced throughout the Solomon Islands campaign.

The strategic context had shifted dramatically during the six weeks since Red first proposed his modification. Japanese air strength in the region had increased as enemy commanders recognized the threat that American forces posed to their southern defensive perimeter. Daily combat operations produced engagement rates that exceeded pilot replacement capacity, creating a tactical environment where any innovation that improved survival rates became strategically significant regardless of its conformity to conventional engineering practice. Red’s promotion to corporal on June 8th, 1943

reflected institutional recognition that his contribution had altered tactical calculations at levels far above his nominal rank. The ceremony conducted on Henderson Fields flight line with minimal formality included presentation of a commendation from Admiral William Holsey whose third fleet depended on air superiority that innovations like the rope system helped maintain.

The language praised Red’s initiative and technical skill while carefully avoiding specific description of the modification itself. maintaining operational security around a capability that Japanese intelligence had not yet identified. The production challenges that rope system installation created reflected broader logistical realities of Pacific theater operations.

Manila hemp, while commercially available in peace time, competed with countless other material requirements in a global war that strained shipping capacity to its limits. Each pound of rope delivered to Henderson Field represented cargo space that could not be used for ammunition, medical supplies, or the countless other consumables that sustained combat operations thousands of miles from industrial centers.

The trade-offs were continuous and often brutal, forcing supply officers to make decisions that would directly affect casualties they would never witness. Red’s solution to the production bottleneck demonstrated the same practical problem solving that had generated the original innovation. Rather than waiting for formal supply channels to deliver sufficient hemp, he organized salvage operations that recovered rope from damaged aircraft, destroyed shipping, and abandoned Japanese installations.

The recovered material required cleaning, testing, and often splicing to achieve sufficient length for installation, but it provided immediate availability that formal procurement could not match. Within 2 weeks, salvage operations were providing 60% of the hemp used in new installations, creating a sustainable production rate that kept pace with squadron demands.

The quality control challenges that salvaged materials created would have horrified peacetime engineers accustomed to working with certified materials and documented specifications. Hemp recovered from various sources exhibited different tensile strengths, elasticity characteristics, and durability profiles that affected system performance in ways that could not be predicted without testing.

RED developed field testing protocols that assessed each rope section’s suitability through loading trials that simulated combat stress, rejecting materials that failed to meet minimum performance standards while accepting variation that formal engineering would have considered unacceptable. The tactical evolution of rope system employment during June and July 1943 revealed capabilities that initial testing had not anticipated.

Pilots discovered that the systems response could be deliberately triggered through high G maneuvers that created structural vibrations similar to weapons impact, allowing them to initiate evasive action when visual observation detected enemy attacks before weapons fire actually struck their aircraft. This adaptation transformed the rope system from a purely reactive defense into a pilot controlled counter measure that enhanced tactical flexibility during complex engagements.

Japanese fighter tactics began adapting to rope equipped aircraft by late June. Though the enemy’s response revealed incomplete understanding of the systems actual operating principles, intelligence reports and interrogation of captured Japanese pilots indicated that enemy commanders attributed American evasive capabilities to advanced radar warning systems rather than mechanical triggers, leading them to develop electronic counter measures that could not affect a purely mechanical defense.

The misunderstanding provided unexpected tactical advantage as Japanese units diverted resources to counter threats that did not exist. While the actual capability remained effective, the kill ratio improvements that rope equipped squadrons achieved during June and July provided statistical validation of RED’s innovation.

Fighter units operating modified P38s recorded loss rates 43% lower than comparable units flying standard aircraft. A difference that translated to dozens of experienced pilots surviving engagements that would otherwise have ended their combat careers. The cumulative effect on squadron effectiveness exceeded simple survival statistics as veteran pilots who survived additional combat missions contributed tactical knowledge and leadership that multiplied the advantage that individual aircraft modifications provided. Captain Maguire’s personal combat record illustrated the rope systems impact on individual

effectiveness. During the eight weeks following his first combat test of the modification, he achieved 11 confirmed aerial victories against Japanese fighters, more than doubling his previous total despite facing increasingly experienced enemy opposition. His success reflected both personal skill and the tactical advantage that red system provided, allowing him to engage in prolonged combat that would have been suicidal in an unmodified aircraft.

His survival and continued effectiveness multiplied the rope systems value beyond what simple defensive capability could achieve.

The technical refinements that emerged from two months of combat operations addressed limitations that initial testing had not revealed. The original hemp rope installation proved vulnerable to tropical humidity, which degraded fiber strength through mold growth and moisture absorption. RED developed treatment processes using salvaged oils and waxes that sealed the rope’s surface while maintaining the flexibility necessary for mechanical operation.

The treatments required reapplication every 3 weeks, creating maintenance requirements that competed with countless other demands on ground crew time. But the alternative was system failure during combat operations. The trigger mechanism’s sensitivity remained problematic throughout the systems operational deployment, requiring constant adjustment as rope characteristics changed through use and environmental exposure.

Mechanisms calibrated for fresh rope often proved too insensitive after several weeks of service, while settings optimized for aged rope would trigger inappropriately when fresh installations were completed. RED established standardized testing protocols that maintenance crews performed before each mission, ensuring that trigger sensitivity remained within acceptable parameters regardless of rope condition or installation age.

The adaptation of rope system principles to other aircraft types proved more challenging than initial optimism had suggested. The P38’s unique twin boom configuration provided mounting points and protected routing paths that single engine fighters could not duplicate. Attempts to install similar systems on P40 Warhawks and F4F Wildcats encountered structural limitations that compromised either installation reliability or aircraft performance.

By August 1943, the rope system remained exclusive to P38 units, creating capability disparities between squadrons that affected tactical planning and mission assignments. The strategic significance of these disparities became apparent during the New Georgia campaign when air support requirements exceeded modified aircraft availability.

Squadron commanders faced difficult decisions about which missions received rope equipped aircraft and which would be flown with standard equipment. Choices that directly affected casualty rates and mission success probabilities. The decisions reflected brutal calculus that characterized Pacific theater operations where resource limitations forced commanders to accept preventable losses in some missions to maximize effectiveness in others considered more strategically significant. Red’s direct involvement in combat operations began

in mid July when squadron losses created pilot shortages that required utilizing any personnel with flight training regardless of their primary occupational specialty. His civilian flying experience, though limited to crop dusters and light aircraft, qualified him for accelerated fighter transition training that would have been impossible under peacetime standards.

The decision to place the rope systems inventor in cockpit reflected both personnel desperation and recognition that his intimate knowledge of the systems capabilities might translate into tactical advantages that formal training could not provide. His first combat mission occurred on July 23rd during an escort assignment for B25 bombers striking Japanese installations on Colombanga.

The mission profile placed him in a defensive role that minimized exposure while allowing him to observe how experienced pilots employed the rope system during actual combat. The engagement that developed tested his ability to apply theoretical knowledge under conditions where mistakes would be measured in casualties rather than failed experiments.

The zero that selected red as its target approached from his high 6:00 position, a classic attack geometry that Japanese pilots had refined through hundreds of combat engagements. Red’s training had prepared him for this moment, emphasizing the importance of maintaining formation while trusting the rope system to provide defensive response when enemy fire actually impacted his aircraft.

The discipline required to not initiate evasive action until the system activated contradicted every survival instinct that human evolution had developed, forcing conscious suppression of reflexes that had kept his ancestors alive. The rope systems activation felt like being struck by a giant’s fist, a violent banking turn that threw him against his restraint harness with force that would leave bruises for days.

The 20 mm rounds that would have torn through his cockpit instead passed through space his aircraft had occupied milliseconds earlier. Their traces visible as orange streaks that marked his near death with geometric precision. The entire sequence from enemy fire to evasive completion consumed less than 1 second.

Yet his perception of time had stretched that interval into an eternity, where each fraction of a moment contained sufficient detail for conscious analysis. The engagement continued as the Zero pilot attempted to reacquire firing solution against a target whose defensive behavior defied his tactical training and combat experience. Red’s subsequent maneuvers combined formal training with instinctive understanding of his aircraft’s capabilities, creating evasive patterns that exploited the rope systems responsive characteristics while maintaining awareness of friendly aircraft positions. His survival through the engagement owed much to luck and the

zero pilot’s eventual ammunition exhaustion, but it validated his belief that the system could protect even relatively inexperienced pilots against opponents whose skill level should have guaranteed their victory. The tactical debriefing that followed Red’s first combat mission revealed insights that theoretical analysis had not anticipated.

The rope systems mechanical response, while faster than human reaction time, introduced control inputs that pilots experienced as violent and disorienting. The abrupt banking turns that saved lives also disrupted situational awareness, forcing pilots to spend critical seconds reorienting themselves spatially before they could resume offensive or defensive maneuvering.

The trade-off between survival and tactical effectiveness represented a compromise that formal engineering might have optimized differently, but combat reality validated red’s pragmatic approach that prioritized keeping aircraft and pilots alive over maintaining perfect tactical positioning. By August 1st, 1943, rope equipped P38s had participated in 73 combat engagements against Japanese fighters, recording 35 confirmed zero victories while sustaining only two aircraft losses to enemy action.

The exchange ratio represented a dramatic improvement over previous months when P38 units had struggled to achieve par maneuverable opponents. Statistical analysis suggested that the rope system contributed to approximately 40% of this improvement with the remainder attributable to improved pilot experience, refined tactics, and better coordination with supporting forces.

The 350 victories that rope equipped aircraft contributed to during this 3-week period represented more than simple statistics in a war of attrition. Each Japanese fighter destroyed eliminated an experienced pilot whose replacement could not match his tactical proficiency, creating cumulative degradation of enemy combat effectiveness that exceeded the immediate tactical impact.

Japanese training programs strained by expanding operational commitments across the Pacific and Asian mainland could not produce pilots with skill levels comparable to the veterans who had begun the war. Every loss accelerated the qualitative decline that would eventually prove more significant than numerical disadvantages.

The psychological impact of the rope system on Japanese fighter operations became evident through intelligence gathered from captured documents and interrogated prisoners. Enemy pilots reported increasing reluctance to engage P38s equipped with what they termed the devil’s reflex, a capability they attributed to supernatural awareness rather than mechanical innovation.

The superstitious interpretation reflected Japanese cultural frameworks for explaining phenomena that contradicted technical understanding, creating morale effects that tactical analysis had not predicted. Pilots who believed they faced opponents with precognitive abilities approached combat with hesitation that affected their aggressiveness and decision-making.

Captain Westbrook’s formal report on the rope system, submitted to Fifth Air Force headquarters on August 7th, recommended immediate expansion of the program to all P38 units operating in the Southwest Pacific theater. His technical analysis documented installation procedures, maintenance requirements, and performance characteristics with precision that would allow other maintenance units to replicate RED’s innovation without requiring his direct involvement.

The report carefully avoided claiming that the system represented a revolutionary breakthrough, instead presenting it as a practical modification that addressed specific tactical challenges through available materials and straightforward engineering.

The response from higher headquarters reflected institutional ambivalence about innovations that emerged from field expedience rather than formal research programs. While the tactical results clearly justified expanded deployment, the rope systems dependence on salvaged materials and non-standard installation procedures created concerns about quality control and long-term sustainability. Staff officers trained in peaceime acquisition processes struggled to accommodate a capability that existed outside established procurement channels and technical documentation standards, creating bureaucratic obstacles that field commanders found frustrating given the systems proven combat effectiveness.

The compromise that emerged authorized continued rope system installation by qualified field maintenance units while initiating formal engineering studies to develop standardized versions that could be manufactured through normal production channels. The dual track approach satisfied institutional requirements for proper documentation and quality assurance while allowing immediate tactical benefits to continue without interruption.

The timeline for standardized production suggested that factory manufactured systems might reach operational units by early 1944, though field personnel understood that Pacific theater priorities often delayed programs that lacked immediate crisis urgency.

Red’s transfer to Fifth Air Force headquarters in Brisbane occurred in mid August, pulling him from the combat theater, where his innovation had proven its value to administrative duties that felt disconnected from the urgent reality of daily air combat. The assignment reflected institutional recognition that his knowledge needed to be documented and disseminated systematically rather than remaining concentrated in one maintenance unit on Guadal Canal.

His new responsibilities included training maintenance personnel from other squadrons, developing standardized installation procedures, and consulting on the engineering studies that would translate his field expedience into formal military specifications.

The transition from hands-on problem solving to bureaucratic coordination revealed aspects of military innovation that Red’s practical focus had not previously encountered. Every decision about rope specifications, trigger mechanisms, and installation procedures required documentation that justified choices to audiences who had never witnessed combat or understood the urgency that drove field modifications.

The process consumed weeks debating details that he had resolved through trial and error in days, creating frustration that reminded him why agricultural problem solving had always appealed more than industrial processes hedged with procedures and approvals. The engineering analysis that formal review produced validated RED’s empirical approach while identifying refinements that systematic study could provide.

Laboratory testing of various rope materials confirmed that Manila hemp offered optimal characteristics for the application, though synthetic fibers under development might eventually provide superior performance. Trigger mechanism studies suggested that hydraulic damping could reduce false activation rates while maintaining response speed, though the added complexity and weight made implementation questionable for field modifications.

The formal documentation that emerged created intellectual property frameworks that would shape postwar patents and commercial applications, translating battlefield innovation into peaceime industrial development. The strategic context for the rope systems deployment shifted dramatically during September 1943 as Allied operations in the Southwest Pacific transitioned from defensive consolidation to offensive campaigns that would drive toward the Philippines and ultimately Japan itself.

The air superiority that innovations like Red’s modification had helped establish became the foundation for amphibious operations that seized Japanese-held islands, establishing forward bases that brought American air power progressively closer to enemy industrial centers. The cumulative effect of tactical advantages measured in seconds and individual aircraft survivability aggregated into strategic capabilities that altered the war’s trajectory.

The last recorded combat engagement involving Red’s rope system occurred on September 14th during the air battle over Lei, New Guinea. A force of 40 P38s, 26 equipped with rope modifications, engaged an estimated 30 Japanese fighters defending against Allied bombing raids. The engagement developed into the largest air battle in the theater since the campaign’s opening months, testing every tactical innovation and training refinement that American forces had developed through 2 years of combat experience.

The rope equipped aircraft’s performance during this engagement demonstrated both the systems tactical value and its limitations when employed against the most experienced Japanese pilots still operating in the theater. Enemy fighters, many flown by veterans with hundreds of combat hours, had developed counter tactics that partially negated the rope systems advantages.

Rather than relying on single firing passes that triggered mechanical defenses, Japanese pilots employed extended pursuit tactics that forced repeated evasive maneuvers, exhausting the rope systems effectiveness through sustained pressure that conventional American tactics had not prepared pilots to counter. The engagement’s outcome reflected the evolution of air combat in the Pacific theater, where tactical innovations by both sides created increasingly complex interactions that defied simple analysis.

Rope equipped P38s recorded seven confirmed victories while sustaining three losses, an exchange ratio that favored American forces, but fell short of the dramatic advantages that earlier engagements had demonstrated. The results suggested that the rope systems tactical surprise value had diminished as Japanese pilots adapted to American capabilities, though its defensive benefits remained significant enough to justify continued deployment.

Red’s last significant contribution to the rope systems development came in October 1943 when he designed an improved trigger mechanism that addressed the sensitivity problems that had plagued field installations. The new design incorporated a hydraulic damper salvaged from landing gear assemblies, creating a system that distinguished between weapon impacts and normal flight vibrations with greater reliability than purely mechanical triggers could achieve.

The modification required more complex installation procedures and added 3 lb to the systems weight. trade-offs that field commanders considered acceptable given the improvement in operational reliability. The production challenges that had limited rope system deployment began resolving during November as formal manufacturing processes came online at military depots in Australia.

Factory-prouced installations incorporated RED’s design refinements while utilizing materials sourced through established procurement channels, eliminating the dependence on salvage operations that had constrained earlier deployment. By December 1943, rope equipped P38s constituted approximately 40% of all P38 aircraft operating in the Southwest Pacific. A concentration sufficient to affect theaterwide tactical calculations.

The strategic assessment of the rope systems overall impact completed by fifth air force intelligence staff in January 1944 credited the modification with contributing to the 35% reduction in P38 combat losses that had occurred between May and December 1943. The analysis carefully noted that multiple factors had influenced this improvement, including better pilot training, refined tactics, increased numerical superiority, and degradation of Japanese pilot quality. Isolating the rope systems specific contribution

proved impossible given the complexity of variables affecting combat outcomes. But correlation analysis suggested that the modification had prevented between 20 and 30 aircraft losses during its first eight months of operational deployment.

The human cost that these statistics represented provided the most meaningful measure of RED’s innovation’s value. Each aircraft loss prevented meant a pilot who survived to fly additional missions, accumulating experience that improved his effectiveness while denying the enemy a victory that would have enhanced their tactical confidence. The cumulative effect of these individual survivals aggregated into squadron level capabilities that shaped operational planning and strategic possibilities.

Air commanders could undertake missions that would have been prohibitively costly without the tactical advantages that modifications like the rope system provided. Red’s personal combat record remained modest by the standards of ACE pilots who dominated public attention and official recognition. His five confirmed aerial victories achieved during 17 combat missions between July and October 1943 placed him in the middle ranks of fighter pilot effectiveness.

But his contribution extended far beyond individual combat success to encompass the systemic improvements that his innovation had enabled. The hundreds of pilots who survived combat because rope systems disrupted enemy attacks represented a multiplication of effectiveness that no individual combat record could match.

The formal recognition that Red received for his innovation came through channels that emphasized technical achievement over combat heroism. The Legion of Merit awarded in February 1944 cited his exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services without specifically describing the rope system or its tactical impact. The citation’s bureaucratic language reflected security concerns about publicizing defensive capabilities while the war continued, but it also represented institutional discomfort with innovations that emerged from unconventional sources and challenged established engineering hierarchies. The

post-war analysis of Pacific theater innovations would eventually credit Red’s rope system as one of several field modifications that collectively improved American tactical effectiveness during the campaign’s critical middle period. Historical assessments placed it alongside drop tank modifications that extended fighter range, forward-firing rocket installations that enhanced ground attack capabilities, and countless other adaptations that emerged from the interaction between combat reality and institutional doctrine. The

pattern these innovations revealed suggested that military effectiveness often depended more on tactical flexibility and rapid adaptation than on technological superiority or doctrinal sophistication. The rope systems operational deployment concluded during mid 1944 as advancing allied forces captured Japanese airfields throughout the Southwest Pacific, eliminating the zero threat that had motivated the modifications development.

The strategic situation had transformed from desperate defense to aggressive offense, creating tactical conditions where the rope systems defensive advantages became less relevant than offensive capabilities that newer aircraft and tactics could provide. By September 1944, the last rope equipped P38s had been withdrawn from combat operations.

Their modifications removed during routine maintenance cycles that transitioned aircraft to standard configurations. The technical legacy that RED’s innovation established influenced post-war military research into automated defensive systems that would eventually produce missile warning receivers, radar warning systems, and the sophisticated threat detection capabilities that modern combat aircraft employ.

The fundamental principle that his rope system embodied using mechanical or electronic means to initiate defensive responses faster than human reaction time allowed became a cornerstone of military aviation doctrine that continues shaping aircraft design decades after hemp rope disappeared from cockpits. Red Harmon’s return to civilian life in 1946 brought him back to the Nebraska farmland where his practical problem-solving instincts had first developed.

The transition from military recognition to agricultural obscurity occurred with minimal ceremony, reflecting both his personal preference for privacy and the military’s institutional tendency to emphasize conventional achievements over unconventional innovations. His rope system, which had saved dozens of American lives and contributed to the air superiority that enabled Allied victory in the Southwest Pacific, became a footnote in official histories that emphasized major battles and strategic decisions over tactical innovations that

had made those victories possible. The interviews that military historians conducted with Redd during the 1950s revealed a man who viewed his wartime contribution with the same matterof fact pragmatism that characterized his approach to farm equipment maintenance. The rope system had solved a specific problem using available materials and straightforward mechanical principles.

Its success reflected practical thinking rather than engineering brilliance. common sense rather than revolutionary insight. The modesty was genuine rather than effected, emerging from a worldview that valued functional solutions over theoretical elegance and measured success by results rather than recognition.

The farm hand, who had threaded Manila hemp through a P38 structure, returned to threading bailing wire through hay equipment, applying the same problem-solving approach to agricultural challenges that had served him during wartime innovation. The rope that had once triggered defensive maneuvers at 400 mph now secured loads that traveled at walking speed, a transition that Red navigated without apparent difficulty or regret.

The contrast between applications mattered less than the continuity of principles. The understanding that every problem admitted solutions if approached with patience, observation, and willingness to challenge assumptions about how things were supposed to work.

News

CH2 The P-51’s Secret: How Packard Engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin Engine

The P-51’s Secret: How Packard Engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin Engine August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside the Packard Motor Car…

CH2 What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected

What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected December 22nd, 1944. One word kept echoing through…

CH2 Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult

Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult The rain that morning in late May…

CH2 When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel

When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel The smell of wood and resin…

CH2 How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon

How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck…

CH2 How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany…

End of content

No more pages to load