How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly

The morning sky above Wake Island was a pale, indifferent blue—so clear it looked almost harmless. At 7:32 a.m. on February 10th, 1942, Lieutenant Commander John Thatch gripped the control stick of his Grumman F4F Wildcat and squinted upward through his canopy, trying to make sense of the black specks descending out of the sun. Six Japanese Zeros were diving fast, their wings flashing in the dawn light. His altimeter read 8,000 feet. His heart, it seemed, was somewhere below the horizon.

He had four Wildcats under his command that morning. Four men he knew personally, whose wives’ names he remembered, whose letters from home he had sometimes censored himself. Now, as the Zero formation dropped toward them in perfect, predatory alignment, he realized his pilots had maybe ninety seconds before they were all dead.

At thirty-seven, Thatch was older than most of the men flying beside him. He had logged 214 flight hours in Wildcats, but not a single confirmed aerial victory against the Zero. The math had always been hopelessly one-sided. The Mitsubishi A6M Zero was lighter, faster, more agile, and could outclimb and outturn his Wildcat at every altitude. Its pilots were veterans—men with hundreds of hours of combat experience gained from China to Pearl Harbor.

The Americans knew the numbers. Everyone did. In one-on-one dogfights, a Zero could get on a Wildcat’s tail in just fourteen seconds. Fourteen seconds to roll, to bank, to cut speed, and the Japanese pilot would have the perfect firing angle. Fourteen seconds to die.

By February, those numbers had already become an epitaph. Forty-three Wildcats had been lost in direct engagements with Zeros. Forty-three pilots buried at sea or listed as missing in action. The reports always sounded the same: Attempted to turn with enemy fighter. Outturned. Shot down.

Every briefing ended with the same warning: Avoid turning engagements. Break off when possible.

But “breaking off” meant abandoning your fellow pilots. It meant running while your friend’s plane burned behind you. It meant hearing your wingman’s last radio transmission cut short by static and knowing you’d never see him again.

Thatch’s squadron—Fighting Squadron 3—was small but tight-knit. Four pilots. Four Wildcats. Four men who believed that if they trusted their leader, they might just make it home. But that morning, trust alone wasn’t going to stop six Zeros from descending on them like hawks on field mice.

Three days earlier, Thatch had been sitting in his quarters at Naval Air Station San Diego, staring at a small pack of wooden matches his wife had mailed him in a care package. The letter inside had been cheerful—something about his son learning to ride a bicycle—but Thatch barely noticed. His mind was locked on a problem that had been haunting him since the first dogfights of the war: how to defeat an enemy you couldn’t outfly.

He picked up two matches and laid them on the table. He moved them in opposite directions, crossing them, weaving them back and forth. The movement was simple but mesmerizing. The matches never stayed apart; they covered each other’s path, overlapping, crossing again and again. Somewhere in that small, absent-minded motion, something clicked.

What if two Wildcats didn’t fight as separate planes? What if they fought as a team?

He tried the pattern again—two matches crisscrossing in a slow figure-eight. One covered the other’s back, then switched roles. He imagined a Zero tailing one plane, closing in for the kill, only to fly straight into the line of fire of the second plane weaving back toward it. The pattern could work—if both pilots trusted each other completely and timed every move perfectly.

It was insane, he thought. It violated every principle the Navy had taught him. Fighter pilots were trained to fight alone—to split up, to find their targets, to engage individually. Two aircraft moving together like dancers in a pattern that left them barely hundreds of feet apart? It was suicide.

But then he thought of the forty-three pilots who had followed orders, fought “by the book,” and died for it.

That night, he called his closest wingman, Lieutenant Edward “Butch” O’Hare, into his quarters. He explained the idea, holding up the matches. O’Hare stared for a long moment, his brow furrowed, then looked up at his commander and said, “When do we try it?”

Now, three days later, Thatch was about to find out whether his “matchstick trick” would save them—or kill them all.

The Japanese had sent eighteen Zeros to sweep the sky over Wake Island that morning, and six of them were already diving toward Thatch’s formation from 11,000 feet. The Wildcat’s altimeter ticked down—10,000… 9,000… 8,000.

Thatch could feel the instinct pulling at him, the urge to scatter, to turn away and fight individually like every American pilot had been trained to do. But he didn’t. His hand went to the radio. His voice was calm, clipped, almost casual. “Weave on my mark.”

To his right, 800 feet away, flew Lieutenant Junior Grade Edward Bassett. Another thousand feet beyond him, Ensign Daniel Sheedy and Ensign Edgar Coulson held their line. Four Wildcats in formation, sunlight gleaming off their navy-blue wings, the sea glinting far below. Above them, six silver Zeros closed in like arrows.

“Basset on me,” Thatch said into his headset. “Weave pattern. Execute.”

He turned his Wildcat toward Bassett. Bassett turned toward him.

The Japanese pilots must have thought the Americans were panicking. The two planes were flying directly at each other, closing fast, only seconds from collision. At 400 yards, both men pulled into opposite banks—Thatch left, Bassett right. They crossed paths with barely 200 feet between them, then turned again, looping back for another pass.

It was a strange, hypnotic motion—two planes weaving through the air in perfect synchronization, like a double helix twisting against the blue.

One of the Zero pilots dove toward Bassett, locking onto his tail. It was textbook Japanese doctrine: close in, stay behind the target, and fire at short range for a guaranteed hit. He lined up his sights, the crosshairs steady, closing to within 500 yards. Bassett was right in front of him, easy prey.

But Bassett didn’t break away. He didn’t roll out or climb. He turned toward Thatch.

The Zero followed, tightening the turn, closing to 400 yards. The pilot probably smiled behind his oxygen mask. He had done this dozens of times before. The American would die in seconds.

Then Thatch’s Wildcat came screaming across the weave from the opposite direction.

The Japanese pilot suddenly found himself flying straight into Thatch’s guns. The American’s six .50-caliber Browning machine guns opened up at 300 yards, spitting out seventy rounds per second. Tracer lines crisscrossed the sky. The Zero pilot yanked his stick hard to the right, pulling into a climb, but it was too late to fire. He broke off. The rest of the formation scattered.

For the first time in the Pacific War, Zeros were running from Wildcats.

Sheedy and Coulson saw what had happened and immediately mirrored the maneuver. They banked toward each other, weaving just as Thatch and Bassett had done. Another Zero dove toward Coulson, locked on, and lined up its sights—but as it fired, Sheedy came slicing through the opposite turn, guns blazing. The Japanese pilot flinched, jerked his stick upward, and disappeared into a cloud.

For six long minutes, the sky above Wake Island erupted in chaos—machine-gun bursts, diving streaks of sunlight, the deep roar of engines throttling at full power. Six Zeros against four Wildcats. By every known rule of aerial combat, the Americans should have been slaughtered. But when the last Zero pulled out and climbed away toward the northwest, every Wildcat was still in the air.

Thatch took a deep breath, checked his instruments, and looked around. No smoke trails. No empty sky where his men should be. Every pilot was alive.

He guided his squadron back toward Ford Island. Forty minutes later, his wheels touched down. The adrenaline drained from his body all at once, leaving his hands trembling on the controls. He shut off the engine, sat in silence, and stared at the gun barrels still warm from firing.

The “weave” had worked.

That afternoon, he filed his combat report. He described the maneuver in precise technical detail, how it forced an attacker into a crossing path with another friendly aircraft, how it turned the Zero’s agility into a liability, how it allowed teamwork to replace speed. He recommended immediate adoption across all fighter units in the Pacific.

Three days later, the response came back from command. A single line, typed neatly and signed by an officer who had probably never been within sight of a Zero.

“Interesting tactic. Requires further testing. Not approved for operational use at this time.”

Thatch stared at the paper for a long time. Forty-three dead American pilots that month alone, and the brass wanted more testing.

He folded the report, placed it in his logbook, and looked out toward the horizon. Somewhere beyond it, the Japanese were already planning their next move—something larger, something that would test not just tactics, but the entire future of naval air warfare.

And when that moment came, he knew, the matchstick trick might be the only thing standing between life and the endless blue below.

Continue below

At 7:32 a.m. on February 10th, 1942, Lieutenant Commander John Thatch watched six Japanese zeros diving toward his four Wildcats over Wake Island, knowing his pilots had maybe 90 seconds before they died. 37 years old, 214 flight hours in Wildcats, zero kills against Zeros.

The Japanese had sent 18 Mitsubishi A6M0 fighters to sweep American patrols from the morning sky. Thatch’s Wildcat was slower. The Zero climbed faster, turned tighter, and could outmaneuver any American fighter at any altitude. Japanese pilots knew it. American pilots knew it. The math was simple and brutal. A Zero could outturn a Wildcat in 14 seconds.

14 seconds to get on your tail, 14 seconds to line up guns, 14 seconds to kill you. By February, the Pacific Fleet had lost 43 wild cats in one versus one dog fights with zeros. 43 pilots who tried to turn with zeros. 43 funerals. The pattern never changed. American pilot sees Zero. American pilot turns to engage. Zero outturns him. Zero shoots him down. Command kept sending the same orders. Avoid turning engagements. Run if possible.

But running meant abandoning other pilots. Running meant letting Zero strafe your buddies while you fled. Thatch commanded fighting squadron 3. Four pilots, four wildcats, four men who trusted him to keep them alive. But he had no answer for the Zero’s turn radius. No answer for its climb rate. No answer except watch good men die.

3 days earlier, Thatch had sat in his quarters at Naval Air Station San Diego, staring at a pack of matches. His wife had sent them in a care package, 20 wooden matches in a thin cardboard box. He’d been thinking about the zero problem for weeks. How do you beat an enemy who can outturn you? How do you survive when the enemy is faster, more agile, and flown by pilots with two years of combat experience? Thatch picked up two matches, held them parallel.

Then he moved them in opposite directions, weaving them past each other. The matches crossed, crossed again, never separated, always supporting each other. And something clicked in his brain. What if two wild cats didn’t fight independently? What if they flew as a pair, weaving back and forth? If a zero got on one wild cat’s tail, that wild cat would turn toward his wingman. The wingman would turn toward him.

They’d cross paths and the zero chasing the first wildcat would fly directly into the second wild cat’s guns. It was insane. It violated every fighter doctrine in the US Navy manual. Fighters fought alone. Pairs stayed together for navigation. But when combat started, you split up and fought one versus one. That was how air combat worked.

That was how every pilot had been trained since 1918. But thatch couldn’t stop seeing those matches weaving together. Couldn’t stop thinking about 43 dead pilots. If you want to see if Thatch’s matchstick weave worked against Zeros, hit that like button right now and subscribe because what happens next is insane. Back to Thatch.

He’d called his wingman, Lieutenant Edward O’Hare, into his quarters that night. Showed him the matches. Explained the weave. O’Hare stared at the matches for 30 seconds. Then he looked at Thatch and asked one question. When do we test it? 4 days later, Thatch was about to find out if his matchstick trick would save lives or get four pilots killed. The six zeros were,200 yd out and closing fast.

His hand moved to the radio. Time to try something that had never been done in combat. Time to find out if two matches could beat six zeros. Thatch’s voice cracked across the radio. Weave on my mark. His wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade Edward Basset, was 800 ft to his right. Two more Wildcats, piloted by Enson’s Daniel Sheety and Edgar Coulson flew another,000 ft beyond Basset.

Four American fighters in a loose line. 6 diving from 11,000 ft. Standard doctrine said, “Split up, turn independently, fight alone.” But thatch keyed his radio and gave an order that had never been spoken in US Navy combat. Basset on me. Weave pattern. Execute. Basset turned his Wildcat toward Thatch. Thatch turned toward Basset. They flew directly at each other. The Zeros dropped to 8,000 ft.

Japanese pilots probably thought the Americans were panicking. Probably thought two Wildcats were about to collide. But thatch and Basset didn’t collide. At 400 yardds, both pilots banked hard. Thatch pulled left. Basset pulled right. They crossed paths with 200 feet separation. Then they kept turning, coming around to cross again. A figure 8 pattern.

Two aircraft weaving back and forth like those matches on Thatch’s desk. The lead zero pilot picked Basset, committed to the tail chase, closed to 600 yd. Standard zero tactic. Get close. Use superior maneuverability. Hammer the target with 20 mm cannon fire. The Zero pilot probably expected Basset to try turning with him.

Probably expected an easy kill, but Basset didn’t turn away from the Zero. He turned toward Thatch. The Zero followed, lining up guns. 500 yd, 400 yd. The Zero pilot had Basset centered in his gunsite, 3 seconds from firing. Then thatch’s wild cat came screaming through the weave pattern from the opposite direction. The zero pilot suddenly had a new problem.

He was chasing Basset, but Basset was flying directly toward another Wildcat, and that Wildcat had guns pointed straight at him. Thatch opened fire at 300 yd. 650 caliber machine guns, 70 rounds per second. The zero pilot had one choice. break off the attack or fly into a wall of bullets. He broke off, pulled hard right, climbed. The other five zeros scattered.

For the first time in Pacific combat, zeros were running from wild cats. She and Coulson had watched the weave work. Now they tried it. She turned toward Coulson. Coulson turned toward Shei. Two more wildats weaving. Another zero committed to Coulson’s tail. got to 400 yardds. Then Shidi came through the weave and the zero pilot flinched, pulled up, disengaged.

The dog fight lasted six minutes. Six Japanese zeros versus four American wild cats. Standard outcome should have been four dead Americans. But when the Zeros finally climbed away and headed northwest, all four wildats were still flying. Thatch checked his fuel, checked his wingmen. Nobody hit, nobody killed. The weave had worked.

Thatch landed at Ford Island 40 minutes later. His hands were shaking, not from fear, from adrenaline. From the realization that maybe, just maybe, American pilots didn’t have to die every time they met zeros. But fighter command wasn’t convinced. Thatch filed his combat report that afternoon, described the weave, explained how it worked, recommended immediate adoption across all fighter squadrons.

The response came back 3 days later. Interesting tactic. Needs further testing, not approved for widespread use. Thatch stared at that response for a long time. 43 pilots dead in February, and command wanted more testing. Meanwhile, the Japanese were planning something bigger.

Something that would test the weave against odds no fighter pilot had ever faced because in 68 days, Thatch would be flying over an island called Midway, and he’d be facing 50 zeros with eight wild cats. Between February and June 1942, Thatch trained Fighting Squadron 3 on the weave every single day. Morning flights, afternoon flights, night formations. When the moon was bright enough, his pilots flew the pattern until they could execute it blind.

Turn toward your wingman, cross, turn back, cross again. Simple in theory, brutal in practice at 300 mph with zeros shooting at you. The Navy still hadn’t officially approved the tactic, but thatch didn’t wait for approval. He taught it to every pilot who would listen, showed them the matches, drew diagrams on blackboards, explained the geometry. If a zero commits to your tail, you turn into your wingman. The zero has to choose.

Follow you into your wingman’s guns or break off. Either way, you survive. Some pilots understood immediately. Others thought Thatch was crazy. One squadron commander told him the weave violated basic fighter doctrine. You can’t fly toward another aircraft in combat. You’ll collide. You’ll panic. You’ll get both pilots killed. But thatch kept teaching because pilots kept dying.

By May, the Pacific Fleet had lost 91 Wildcats in combat with zeros, 91 funerals, 91 letters to families, and fighter command still issued the same orders. Avoid engagement when possible. Run if outnumbered. The orders might as well have said, give up and die. Then naval intelligence intercepted Japanese radio traffic.

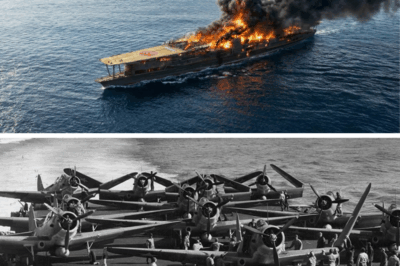

Code breakers at station Hypo and Pearl Harbor decrypted the messages. The Japanese were planning a massive assault on Midway Island. Four aircraft carriers, 270 aircraft, the largest carrier operation in Japanese naval history. The attack was scheduled for June 4th, 1942. Admiral Chester Nimttz called every available carrier to Pearl Harbor.

He had three, Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet. The Japanese had four, plus two years of combat experience, plus zeros that could outfly anything America had. The math was nightmare fuel. American carriers were outnumbered. American pilots were outmatched. And Midway Island had a runway that Japanese bombers would turn into rubble in the first 30 minutes.

Fighting squadron 3 got deployment orders on May 26th. Report to USS Yorktown. Prepare for carrier operations. Thatch read those orders and understood what they meant. His squadron would be flying combat air patrol over Yorktown when the Japanese attacked, protecting the carrier from bombers, fighting zeros, maybe dying. He gathered his pilots that evening.

Seven men, seven wildats, seven lives depending on a trick with matches that the Navy still hadn’t officially approved. Thatch showed them the matches one more time, explained the weave one more time. Then he told them the truth. The Japanese are bringing 50 zeros to Midway. Maybe more. We’ll have eight Wildcats.

Maybe fewer if Enterprise or Hornet lose fighters before the battle. The only way we survive is the weave. The only way we protect Yorktown is the weave. The only way we win is the weave. One pilot asked the obvious question.

What if it doesn’t work? What if we weave and the zeros just shoot us anyway? Thatch didn’t have a good answer. He just showed them the matches again. Showed them how two matches weaving could cover each other, could protect each other, could survive together when surviving alone was impossible. Yorktown sailed from Pearl Harbor on May 30th. 4 days to Midway.

4 days to prepare for a battle that would decide the Pacific War. four days to pray that a matchstick trick would work when 50 zeros came screaming out of the sky. Because on June 4th at 0930 hours, Thatch would look up and see something no American pilot had ever faced. A sky completely black with Japanese fighters. June 4th, 1942, 0930 hours.

Thatch was at 14,000 ft above Yorktown when the first Japanese strike wave appeared. 18 Aichi dive bombers escorted by 12 zeros. Not 50. Not the massive formation intelligence had predicted, but 12 zeros was still 3:1 odds against thatch’s four plane section. The zeros came in high 15,000 ft. Standard Japanese doctrine. Establish altitude advantage. Dive on American fighters. Use speed and maneuverability to dominate the fight.

Thatch counted the enemy aircraft. Counted his own. Four wild cats, 12 zeros. His hand keyed the radio. Weave pattern. Execute on my mark. His wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade Edward Basset, was 600 ft to his right. Two more Wildcats behind them. The Zeros dove. Thatch watched them commit. Watched them pick targets. Three zeros broke toward Thatch.

Four went after Basset. The others continued toward Yorktown. Thatch gave the order. Mark, execute. He turned hard toward Basset. Basset turned toward him. They crossed paths at 12,000 ft. The three zeros chasing Fch suddenly had a problem. Their target was flying directly at another Wildcat, and that Wildcat’s guns were pointing at them.

The lead zero pilot hesitated just for 2 seconds, but 2 seconds at combat speed is 400 yd. Thatch came through the weave and opened fire. 50 caliber rounds ripped through the Zero’s engine cowling. The zero rolled left, trailing black smoke, fell away. Thatch’s first zero kill, but the other two zeros didn’t break off. They’d seen the weave, understood the pattern, and they adapted.

Instead of committing to Thatch’s tail, they split. One went high, one went low. They tried to attack from different angles, forced Thatch to choose which threat to counter. Thatch pulled into a climbing turn toward the high zero. Basset broke toward the low zero. The weave pattern fractured for 6 seconds. Both Wildcats were fighting independently. Exactly what Thatch had tried to avoid.

The High Zero got guns on Thatch at 800 yd. 20 mm cannon fire walked up Thatch’s left wing. Two rounds punched through the wing route. One went through his cockpit canopy 3 in from his head. Thatch felt the shock wave. Felt aluminum fragments hit his flight suit. Kept turning. Basset called over the radio. I’m hit. Repeat. I’m hit. Thatch looked left.

Basset’s wildcat was trailing white smoke. Coolant leak. Maybe worse. The low zero was still on his tail, hammering him with machine gun fire. Thatch made a choice. Abandoned his turn toward the high zero. Dove toward Basset. The weave had broken, but the principle still worked. Get between your wingman and the threat.

Thatch came down on the low zero from 7:00 high. 600 yds, 500, 400. He opened fire. The zero exploded. Pieces of wing and fuselage tumbled through the air. Basset’s wildcat was shaking, losing altitude. He called over the radio, “Enine’s overheating. I’m heading back to Yorktown.” Thatch told him, “Go.” Told the other two Wildcats to escort him. That left Thatch alone at 11,000 ft with 10 zeros still in the sky.

The weave worked with a wingman. Without a wingman, Thatch was just another Wildcat pilot trying not to die. He turned toward Yorktown, started descending. 30 saw him, turned to intercept. Thatch looked around for friendly fighters. Saw four Wildcats from another squadron 3 mi east. Too far to help. The three zeros were closing.

Thatch had no wingman, no weave, no options except run. But running meant leading zeros toward Yorktown, leading them toward the carrier his squadron was supposed to protect. He keyed his radio, called for help, told the other Wildcats he was engaging three zeros solo. Told them if the weave worked, they’d see proof. If it didn’t work, tell his wife he loved her.

Thench turned his Wildcat toward three zeros and prepared to test whether a matchstick trick could save one pilot’s life. Thatch was at 9,000 ft when the three zeros reached firing range. He was alone. No wingman to weave with, no support. But he’d spent 4 months thinking about the weave. 4 months understanding the geometry. And he realized something. The weave didn’t require two aircraft. It required two points in space.

He turned hard right, then immediately reversed left. Sharp angular turns, not the smooth turning fight zero’s expected. The lead zero committed to follow Thatch’s right turn, but Thatch was already reversing left. The zero pilot had to correct, had to pull harder, had to burn energy. Thatch did it again. Right turn, left reversal.

The Zero followed right, Thatch went left. The Japanese pilot was always half a second behind, always correcting, always reacting. And every correction cost speed, cost energy, cost the altitude advantage. After 40 seconds of reversals, the Zero was co-altitude with Thatch.

Same speed, same energy state, no advantage. The zero pilot broke off, climbed away. The other two zeros followed him. Thatch had just proven something critical. The weave principle worked even without a wingman. Sharp reversals, constant direction changes. Never let the enemy predict your next move. Make them react. Make them bleed energy. Make them quit.

He landed on Yorktown 20 minutes later. Basset was already aboard. His Wildcat had taken four hits, but the engine held together long enough to reach the carrier. The other pilots from Fighting Squadron 3 were debriefing in the ready room. They’d all seen Thatch’s solo fight. All watched him survive three zeros alone.

Word spread through the fighter squadrons that afternoon. Thatch’s weave works, even solo, even outnumbered. By evening, pilots from Enterprise and Hornet were asking Thatch to explain the tactic. He showed them the matches, drew diagrams, demonstrated the reversals. Some pilots tested it that night.

Pair flights over the carrier groups, practicing the weave, learning the timing. By June 5th, 18 Wildcat pilots could execute the pattern. By June 6th, 32 pilots, the weave was spreading through the fleet faster than any official doctrine ever had. Japanese pilots noticed radio intercepts from June 7th included references to new American tactics, American fighters flying in coordinated pairs, American fighters executing unpredictable maneuvers, American fighters that refused to die. One intercepted message

from a Japanese fighter commander said, “American Wildcat pilots have changed their methods. Expect increased resistance.” On June 10th, Fighting Squadron 3 flew combat air patrol over a convoy near Midway. Eight Wildcats. 14 Zeros attacked. Thatch called the weave. All four pairs executed.

The Zeros tried their standard tactics, tried to isolate individual Wildcats, tried to use superior maneuverability. But every time a zero committed to a wild cat’s tail, that wild cat turned toward his wingmen. Every time the zeros tried to split a pair, both wild cats turned toward each other. The pattern held.

After 12 minutes, the Zeros broke off. They damaged two Wildcats, but scored zero kills. The Americans had shot down three zeros. Three confirmed kills. First time in Pacific combat that Wildcats had a positive kill ratio against Zeros in a major engagement. Fighter Command finally took notice. On June 15th, Commander John Thatch received orders to report the Pearl Harbor.

Report to Admiral Nimmitz, prepare a formal briefing on the weave tactic. The Navy wanted to evaluate whether this matchstick trick should become official doctrine. Thatch arrived at Pearl Harbor on June 18th. Spent two days preparing the briefing. Prepared diagrams, combat footage, pilot testimonials, kill ratios, survival statistics, everything command needed to see that the weave worked.

But while thatch was preparing his briefing, Japanese intelligence was preparing something else. They’d analyzed the new American tactics. They’d studied the weave pattern and they developed a counter tactic, a way to break the weave, a way to kill both Wildcats at once. On June 21st, Thatch would brief Admiral Nimmits on the weave.

But on June 23rd, Fighting Squadron 3 would face 18 zeros over Santa Cruz Island, and those zeros would be using tactics specifically designed to destroy the Thatche. June 23rd, 1942. 0815 hours, Santa Cruz Island. Fighting squadron 3 was escorting a convoy when radar picked up contacts. 18 bogeies inbound from the northwest. Distance 12 m.

Thatch counted his wildcats, eight aircraft, four pairs, standard weave formation. He’d briefed Nimttz 3 days earlier. Nimttz had authorized field testing of the weave across all Pacific fighter squadrons. Now Thatch was about to discover that the Japanese had done their homework, too. The Zeros came in at 16,000 ft, but they didn’t dive immediately. They circled, waited.

Thatch watched them orbit at altitude for 90 seconds. Strange behavior. Zeros always attacked immediately. Always used altitude advantage fast before Americans could climb. But these Zeros were waiting for something. Then Thatch understood. The zeros were coordinating. Six zeros broke left. Six broke right. Six stayed high.

Three groups, three angles of attack. They’d seen the weave. They knew two wild cats could protect each other from one direction, but three directions simultaneously. That was different. The attack came at 0817. 6 do from high. Six came in from the left flank. Six from the right. Thatch called the weave, but his pilots hesitated.

Which threat do you counter when threats are coming from three directions? Lieutenant Basset chose the high zeros, turned into them, but that exposed his right flank to the right side group. Ensenidi turned to cover Basset’s right, but that broke the weave pattern with his own wingmen. Suddenly, all four pairs were fragmented. Eight wild cats fighting independently.

Exactly what the Japanese wanted. Thatch saw it happening. saw the weave collapsing. Keat’s radio. Reform pairs. Lock onto your wingmen. Execute standard weave. Ignore the other groups. His pilots heard him. Basset turned hard toward his wingman, found him, locked in. They executed the weave even with zeros attacking from multiple directions. The high zeros dove.

Basset turned toward his wingman. The zeros followed, flew into his wingman’s guns. Two zeros exploded. The others pulled up. The left group tried next. Came in at 14,000 ft. Thatch and his wingman executed the weave. One zero committed. Flew through the crossing pattern. Took 50 caliber rounds through the cockpit. Fell away smoking.

The right group attacked Shedi’s pair. Same result. Weave held. Zero crashed. After 8 minutes, the Japanese had lost five zeros. The Americans had lost zero wildats. The coordinated three direction attack had failed. The Zeros climbed away. But thatch knew something critical had just happened. The Japanese had adapted. They’d studied the weave.

They developed counter tactics. The fact that the counter tactics failed didn’t matter. What mattered was Japanese command was taking the weave seriously. taking it seriously enough to train pilots specifically to defeat it. That evening, Thatch filed a combat report, described the three direction attack, described how the weave held, even under coordinated assault, recommended immediate widespread adoption, no more testing, no more evaluation.

The weave worked against standard tactics. It worked against adapted tactics. It worked. period. The report reached Admiral Nimttz on June 25th. Nimttz forwarded it to Admiral King, commander-in-chief of the US fleet. King read it, read the kill ratios, read the survival statistics, zero American losses, five Japanese losses, eight Wildcats versus 18 zeros.

On June 29th, Admiral King issued Fleet Order 41-1942. All fighter squadrons in the Pacific Fleet would immediately adopt the thatchweave as standard combat doctrine. Mandatory training for all pilots, mandatory execution in all engagements. The matchstick trick was now official US Navy tactics. But orders from Washington took time to reach every squadron.

Time to train pilots, time to practice the pattern, and the Japanese weren’t waiting. On July 7th, over Guadal Canal, 32 zeros would attack 12 Wildcats from six different squadrons. Some squadrons knew the weave, some didn’t. And the ones that didn’t would learn the hard way why thatch had been teaching matches for 5 months.

July 7th, 1942, Guadal Canal. 12 Wildcats from six different squadrons flew combat air patrol over Henderson Field. Four pilots had trained on the Thatche. Eight had not. At 11:20 a.m., 32 zeros appeared from the north. The four pilots who knew the weave immediately paired up, executed the pattern. The eight who didn’t know it fought independently. Traditional one versus one dog fighting.

22 minutes later, six wild cats were shot down. All six were pilots who fought independently. The four pilots using the weave survived without damage. They claimed seven zero kills between them. Admiral Hollyy read that combat report and immediately issued orders. Every fighter pilot in the South Pacific would learn the thatchweave within 2 weeks.

No exceptions. Training programs started on July 10th. Thatch flew to Guadal Canal, spent three weeks teaching the weave to every squadron on the island. Morning briefings, afternoon flight training, evening debriefs. He showed pilots the matches, drew the diagrams, flew demonstration patterns. Some pilots learned in two days, others needed a week, but every pilot learned.

By August 1st, 96 Wildcat pilots could execute the weave. By September 1st, 214 pilots. The tactic spread from the Pacific to the Atlantic, from carriers to land bases, from wildcats to other aircraft types. P38 Lightning squadrons started using it. P40 Warhawk squadrons. Even some bomber formations adapted the crossing pattern for defensive purposes. The results were immediate and dramatic.

In June 1942, before the weave became doctrine, American fighters had a killto- loss ratio of 0.4 4 to1 against zeros. For every 10 American fighters lost, Americans shot down four zeros. By October 1942, after widespread weave adoption, the ratio was 2.1:1. Americans were shooting down two zeros for every Wildcat lost.

Japanese pilots hated it. Radio intercepts from September showed Japanese squadron commanders warning pilots about the American crossing pattern. Do not commit to tail chase. do not follow American fighters into their wingman’s guns. Disengage if Americans execute coordination tactics.

But disengaging meant losing the fight, meant letting American fighters protect their bombers, meant giving up air superiority. The Zero was still faster and more maneuverable than the Wildcat, but speed and maneuverability meant nothing if you couldn’t get guns on target. and the weave made it almost impossible to get guns on target.

By January 1943, the weave was standard doctrine across all US fighter squadrons. Army Air Force adopted it, Marine Corps adopted it, British Royal Navy pilots started learning it for their carriers. The tactic that started with two matches on a desk in San Diego had become the foundation of Allied fighter doctrine. Thatch received the Navy Cross in February 1943.

The citation read, “For extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the development of fighter tactics that have saved numerous American lives and contributed significantly to the success of US naval aviation operations.” But thatch didn’t care about medals. He cared about numbers.

In the 6 months before the weave, the Pacific Fleet lost 137 Wildcats in combat with zeros. In the 6 months after the weave became doctrine, the fleet lost 41 wildats. 96 pilots who came home because two matches could cross paths. Fighter Command assigned Thatch to training duty in March 1943, pulled him from combat operations, sent him back to San Diego to teach the weave to new pilots. He hated it.

Hated being away from the fight, but command told him he was more valuable as an instructor than as a combat pilot. More valuable teaching the trick than using it. Thatch trained pilots for 18 months. Talk the weave to over 800 naval aviators. Every one of those pilots took the tactic to combat. Every one of them survived situations they shouldn’t have survived.

And every one of them told other pilots about the commander who saved their lives with matchsticks. The war ended in August 1945. Thatch was 40 years old. He’d flown 73 combat missions, scored six confirmed kills, received the Navy Cross, two distinguished flying crosses, and three air medals. But none of that compared to the number that mattered. Over 2,000 American pilots survived the war because they knew how to weave.

After the war ended, Thatch faced a choice. Stay in the Navy or return to civilian life. His wife wanted him home. His children barely knew him. He’d been gone for 4 years. But staying in the Navy meant continuing to teach, continuing to save lives. What would a man who saved 2,000 pilots with matchsticks do when the shooting stopped? John Thatch stayed in the Navy.

He couldn’t walk away from teaching. Couldn’t walk away from pilots who needed to survive. He spent the next 27 years training fighter pilots, developing tactics, saving lives without firing a shot. The Navy promoted him to commander in 1946, captain in 1952, rear admiral in 1960.

He commanded carrier groups during the Korean War, never flew combat again, but his pilots did, and every one of them knew the weave. Korean War fighter pilots called it the Thatche officially. No other tactic in military history carried a pilot’s name while he was still alive. During Vietnam, the weave evolved. F4 Phantom pilots adapted it for supersonic speeds. Called it fluid 4 formation.

Same principle, same crossing pattern, different speeds. American pilots used it against North Vietnamese MiGs. The MiG 17 could outturn the F4 just like the Zero outturned the Wildcat. But the Weave worked at 600 mph the same way it worked at 300. Thatch retired from the Navy in 1973. Four-star admiral, 40 years of service.

He moved back to San Diego, lived quietly, didn’t talk much about the war, didn’t talk about Midway or Guadal Canal or the 2,000 pilots. When reporters asked about the weave, he always said the same thing. It wasn’t genius. It was desperation. I just wanted my boys to come home. Fighter pilots never forgot him.

Every year on February 10th, the anniversary of the first weave combat test, naval aviators from around the country would call Thatch, thank him, tell him stories about how the weave saved their lives or their wingman’s life. Thatch listened to every story, remembered every name.

The Navy named a building after him in 1981, Thatch Hall at Naval Air Station Pensacola, fighter pilot training facility. Every naval aviator who earns their wings walks past a bronze plaque with Thatch’s face and three words: innovate, adapt, survive. Thatch died on April 15th, 2001, 86 years old. His funeral at Arlington National Cemetery drew over 300 naval aviators.

Many were in their 70s and 80s. Men who’d flown Wildcats in 1943. Men who’d flown Phantoms in 1967. Men who’d flown Hornets in 1991. All of them alive because one commander thought about matchsticks. Today, the thatchwave is still taught at every fighter pilot school in the United States military. Navy, Air Force, Marines.

Modern versions adapted for stealth fighters and beyond visual range combat. But the principle never changed. Two aircraft protecting each other, turning toward each other, crossing paths, surviving together. The National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola has Thatch’s original pack of matches preserved in a glass case next to a model F4F Wildcat.

The label says Lieutenant Commander John Thatch used these matches to develop the tactical innovation that saved over 2,000 American pilots during World War II. School groups walk past that case every day. Most don’t stop, but fighter pilots always stop. They look at those matches. They understand. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people.

Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every week. Stories about pilots and commanders who saved lives with matchsticks and courage. Real people, real heroism.

News

CH2 Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky The air above Rapopo…

CH2 Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons

Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons At 6:15 on…

CH2 What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History

What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History In the spring…

CH2 Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted

Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted At precisely…

CH2 Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland It…

CH2 Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division

Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division June 6th, 1944. 02:15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy….

End of content

No more pages to load