How Music Became The Messenger of War – Revealing The Forgotten Night Japanese Soldiers Tuned Into Glenn Miller and Realized the War Was Already Lost

The jungle never slept.

On Guadalcanal, the air hung thick as oil, every breath heavy with the scent of rot and rain. Crickets screamed from the trees, and the mud clung to everything like memory. Beneath a canopy of dripping palms, in a small tent lit only by the red glow of a single bulb, Corporal Hideyaki Tanaka sat hunched over a battered shortwave receiver.

It was January 17th, 1942. Midnight.

His fingers, cracked from humidity and grime, turned the tuning dial by instinct—slowly, delicately, the way a man might coax a ghost out of static. The machine hissed and whispered, the sound of distant thunder bleeding through the wires. Somewhere, hundreds of miles away, a signal cut through the noise like a blade.

And then he heard it.

A bright, brassy swing, sharp as sunlight, danced through his headphones. A saxophone crooned a melody that made no sense in this world of mud and malaria. Trumpets followed, full of energy and joy. Then came that rhythm—steady, irresistible, alive. The song was “In the Mood.”

Tanaka froze.

He had never heard anything like it. Not the somber marches of the Imperial Army, not the shrill flutes and drums of his village festivals, not even the stern European waltzes his instructors had played years before. This was something else. It didn’t march. It moved. It laughed.

He knew he shouldn’t be listening. His orders were strict: monitor enemy transmissions, identify Allied code signals, report everything to headquarters. But this wasn’t code. It was… life. It was the sound of a world far away from his, a world untouched by starvation, untouched by fear.

The song ended. Another began. Then another.

Through the headphones, the jungles disappeared. He could almost see it—New York, perhaps, or Los Angeles. Men in crisp suits, women in shimmering dresses, a room full of laughter and light. The horns swung, the drums rolled, and the entire nation seemed to dance on air. America.

Tanaka pulled the headset away, staring at the radio as if it had conjured a spirit. His tentmate, Sergeant Ito, looked up from his cot, a cigarette burning between his fingers.

“What is it?” Ito asked.

Tanaka hesitated. “Music,” he said finally. “From the Americans.”

Ito frowned. “Turn it off. It’s enemy propaganda.”

But Tanaka didn’t. He pressed the headphones back to his ears.

Enemy propaganda? he thought. No. This isn’t propaganda. Propaganda was what they broadcast from Tokyo—metallic voices shouting of honor, duty, sacrifice. This… this was something softer. Stranger. It wasn’t telling him what to believe. It was showing him what it felt like to be free.

He didn’t understand the words, but he understood the tone. It was confidence—not the forced kind his officers barked before battle, but something deeper, something easy. It was the sound of a people who didn’t fear tomorrow.

For a moment, Tanaka forgot where he was. The mosquitoes, the fever, the hunger—all vanished. He closed his eyes and let the brass wash over him.

Then, as if remembering himself, he yanked the cord from the receiver.

Outside, rain began to fall. It came hard and fast, pounding the tent like drumbeats. Tanaka sat motionless, listening to the rain fade into the jungle’s roar. He had felt something strange—something dangerous. He didn’t have words for it yet. He only knew that for the first time since leaving home, he had heard beauty that didn’t belong to Japan.

The next morning, he said nothing. Neither did Ito. But when night came again, Tanaka returned to the radio.

Each night after, he tuned in. And each night, the songs came.

Sometimes it was Glenn Miller again—“Moonlight Serenade,” smooth as glass. Sometimes it was Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw. Sometimes there were voices—American announcers with voices like velvet, reading news he couldn’t understand but whose tone alone carried reassurance. Calm. Certain. The sound of a nation at ease even in war.

Tanaka listened in secret, long after the others had fallen asleep. And he wasn’t alone.

Across the Pacific, Japanese radio operators did the same. From jungle outposts in New Guinea to lonely bunkers in the Solomons, from submarines surfacing in the black Pacific to mountain bases in Burma, men tuned in to the forbidden frequencies. At first by accident. Then by choice.

The Americans’ signals were too strong to block. They bled into every channel, roaring across the ocean with a power that no Japanese transmitter could match. Even the static of storms couldn’t silence them.

At first, Tanaka told himself he was studying the enemy. That he was analyzing their technology, gauging the strength of their transmitters. That this was military duty. But deep down, he knew that wasn’t true.

Continue below

January 17th, 1942. Somewhere in the humid darkness of a jungle outpost on the eastern edge of Guadal Canal, a young Japanese radio operator named Corporal Hideyaki Tanaka sat hunched over his equipment, headphones pressed tight against his ears. The air was thick with moisture, the kind that made everything feel heavy, uniforms, breath, even thought itself.

Outside the canvas tent, the jungle screamed its nightly chorus, insects thrumming in waves, the distant call of nightbirds, the rustle of something moving through undergrowth. But inside, through the crackle and hiss of shortwave interference, another sound emerged. Brass instruments, bright and impossibly clean, cutting through static like sunlight through storm clouds.

A saxophone melody smooth as silk, followed by the synchronized precision of an entire orchestra swinging in perfect time. It was Glenn Miller’s in the mood transmitted from somewhere across the vast Pacific. And for a moment, just a moment, Corporal Tanaka forgot about the war entirely. He should not have been listening.

Standing orders were clear. Monitor enemy communications. Intercept military frequencies. gather intelligence. But the American music stations broadcast so powerfully with such overwhelming signal strength that they bled into every frequency they were impossible to ignore. And something about this music, this strange American sound, made him pause.

His hand, which had been reaching to adjust the dial, froze. The melody was unlike anything he had heard before. Not the military marches that had accompanied his training, not the traditional shakuhachi flute music of his childhood, not even the western classical compositions that Japanese officers sometimes played on photographs during evening recreation.

This was something else entirely, something that seemed to contain within its rhythm a kind of confidence, a carelessness, an abundance that felt as foreign to him as the idea of surrender. The recording had been made in a New York studio just months earlier, pressed onto shellac discs by the thousands, then transmitted from US armed forces radio stations powerful enough to reach across oceans.

The big band sound, as it was called, had become the unofficial soundtrack of American military life, broadcast to troops across every theater of war, a reminder of home, of normaly, of the world they were fighting to preserve. But it was also inadvertently psychological warfare of the most effective kind.

Because every Japanese soldier who heard it, every German submariner who picked up the signal while surfacing in the Atlantic, every Italian garrison operator who stumbled across it while scanning frequencies heard the same thing. The sound of a nation so rich, so industrially powerful, so confident in its own survival that it could afford to swing. This is the story of what happened when the music of America reached the ears of its enemies and how a big band sound carried within it the truth of industrial might, ideological difference and the vast unbridgegable gap between

two ways of life. It is the story of moments like Corporal Tanakas repeated thousands of times across the Pacific and European theaters when enemy soldiers heard not propaganda but something far more devastating, the casual everyday expression of American abundance.

And it is the story of how music that most abstract of human creations became one of the most concrete measures of military industrial supremacy. the strategic landscape of sound. To understand what Glenn Miller’s music meant in the context of the Pacific War, we must first understand the world from which Japanese soldiers came and the world they believed they were fighting to protect.

Japan in 1942 was a nation that had spent decades racing to catch up with Western industrial powers. A country that had modernized at breathtaking speed, but remained in critical ways economically fragile. The Japanese military industrial complex, for all its tactical brilliance and warrior spirit, operated on razor thin margins. Resource scarcity defined every aspect of military planning.

Oil reserves were critically low, which was precisely why the southern operation had been launched in the first place, targeting the resourcerich territories of Southeast Asia. Steel production, while impressive by Asian standards, remained a fraction of American capacity. Food supplies for troops were calculated down to the last grain of rice. This scarcity was not merely economic.

It was philosophical, cultural, spiritual. Japanese military training emphasized deprivation as a virtue. Soldiers were taught that hardship purified the spirit, that suffering brought one closer to the warrior ideal of Bushidto. Rations were deliberately sparse. Comfort was seen as weakness. The entire ideological framework of Japanese militarism was built on the concept of discipline through denial, of strength through sacrifice. Every soldier knew that his family at home was making sacrifices as well, that the entire

nation was mobilized in a collective effort that demanded austerity from everyone. This shared hardship was supposed to be a source of unity, of spiritual strength that would compensate for material disadvantage. Against this backdrop, American abundance was not just surprising. It was philosophically incomprehensible.

The United States in 1942 was the world’s largest economy by an almost absurd margin. American steel production alone exceeded the combined output of Germany, Japan, and Italy. US shipyards were launching new vessels at a rate that Japanese planners had considered impossible when they calculated the strategic balance before Pearl Harbor.

American factories were transitioning to war production with an efficiency that shocked Axis intelligence analysts. And crucially, American civilian morale remained high, sustained by a standard of living that Japanese citizens could scarcely imagine. This economic disparity manifested in countless ways on the battlefield, but perhaps none quite so psychologically powerful as the matter of music.

The US military understood in a way that seems obvious in retrospect but was revolutionary at the time that troop morale was not merely about speeches and propaganda but about maintaining a connection to home to normaly to the cultural life that soldiers were fighting to defend.

The armed forces radio service established in 1942 was an explicit recognition of this principle. Its mission was to broadcast music, entertainment, and news to American troops wherever they were stationed. And because radio waves do not respect boundaries, those broadcasts reached far beyond their intended audience. Glenn Miller by 1942 was already one of the most popular band leaders in America.

His orchestra had topped the charts repeatedly, his recordings sold in the millions. When he dissolved his civilian band to enlist and form the Army Air Force Band, it was front page news. The decision was both patriotic and strategic. Miller understood that music was essential to morale, and he was determined to bring the sound of home to soldiers overseas.

What neither he nor military planners fully anticipated was how that sound would be interpreted by the enemy. Corporal Tanaka was not alone in his nocturnal discovery. Across the Pacific theater, Japanese radio operators encountered American broadcasts with increasing frequency as the war progressed. The experience was by all accounts profoundly disorienting.

Here is what they heard. Not just music, but the sheer production quality of that music. the clarity of the recordings, the size of the orchestras, the fact that America could afford to have its best musicians in uniform forming entire military bands when Japan was struggling to keep enough men in factories to produce ammunition.

Every note of Glenn Miller’s arrangements was a testament to excess, to resources spent on something as militarily useless as entertainment. But it was more than mere sound quality. The music itself carried cultural information that Japanese soldiers found baffling and increasingly demoralizing. Big band swing was fundamentally democratic music.

Unlike the top- down hierarchical structure of military marches or the formal compositions of classical music, swing was collaborative, improvisational, energetic. Soloists took turns, riffing off each other, while the full orchestra provided rhythmic support. There was a looseness to it, a sense of controlled freedom that reflected something essential about American culture, individual expression within collective effort, competition within cooperation.

Jazz, from which swing descended, was African-American music that had been adopted, adapted, and commercialized across racial lines. Itself a complicated story of cultural appropriation and musical innovation, but one that demonstrated a kind of cultural flexibility and exchange that had no parallel in Japanese society.

Japanese soldiers listening to these broadcasts heard music that suggested a society fundamentally different from their own. Where Japanese military culture emphasized uniformity, American music celebrated variation. Where Japanese training demanded the subordination of self to unit, American swing featured individual soloists stepping forward to take the spotlight.

Where Japanese propaganda spoke constantly of sacrifice and hardship, American music sounded, there was no other word for it, fun, joyful, exuberant, the sound of a people who expected not just to survive the war, but to enjoy life while fighting it. This was cognitive dissonance on a grand scale.

Japanese soldiers had been told repeatedly and from the highest authorities that America was a decadent nation weakened by luxury, divided by individualism, lacking the spiritual unity and warrior discipline that would ensure Japanese victory. The greater East Asia co-rossperity sphere propaganda emphasized Western moral decline, American racial disunityity, the chaos of democratic politics.

Japanese troops were taught to view American soldiers as soft, undisiplined, too accustomed to comfort to endure real hardship. This narrative was essential to Japanese military morale, especially as the war turned against them. If Japan could not match American material superiority, and it was becoming increasingly clear that it could not, then Japanese forces had to believe in their spiritual superiority. But the music told a different story.

It told a story of a nation with resources to spare, with energy to burn, with confidence so deep it could afford to swing while fighting a two-front war. And as Japanese soldiers listened, sometimes by accident, sometimes deliberately, often in secret, the gap between what they had been told and what they were hearing grew impossible to ignore.

Private first class Yoshio Nakamura in a letter home that was intercepted and translated by American intelligence after the war wrote about hearing American radio broadcasts from his position on Bugganville in late 1943. The enemy music plays all night every night. It is not like our military songs. It sounds like a celebration, like they are not afraid.

Our officers tell us the Americans are weak, but their music does not sound weak. It sounds like the music of people who have so much they can waste it on soldiers. We receive one rice ball per day now, and the taste is often spoiled, but the Americans, even their music is rich. This was the psychological effect that military planners had not anticipated.

Propaganda could be dismissed as lies. Claims about industrial production could be written off as exaggeration. But music was immediate, visceral, impossible to disbelieve. You could hear the size of the orchestra. You could hear the quality of the instruments. You could hear in the very structure of the sound, evidence of a society that was not struggling, not starving, not sacrificing entertainment for survival.

The music was proof. If we are to find a single recurring symbol in this story, a physical object that represents the ideological and material gap between America and Japan, it is not a weapon or a vehicle, but something more mundane and more devastating, the radio itself. Specifically, the American broadcast radio powerful enough to reach across oceans, consistent enough to maintain programming day after day, sophisticated enough to deliver highfidelity music to listeners thousands of miles away. Japanese military radios were

functional, often excellent for their intended purpose of tactical communication, but they were built under conditions of resource scarcity, designed for efficiency rather than power, for military traffic rather than entertainment. American broadcasting equipment, by contrast, was a product of the world’s most advanced electronics industry, backed by unlimited copper for wiring, unlimited energy for transmission, unlimited resources for maintenance and upgrades.

The contrast was not subtle. Japanese operators could hear the difference in signal strength, in clarity, in the consistency of programming. American stations broadcast 24 hours a day. Japanese forces could barely keep their own communication networks functioning as supply lines stretched and fuel grew scarce. The radio became a symbol of everything else of if America could build transmitters this powerful, what else could they build? if they could afford to broadcast music continuously across thousands of miles of ocean, what did that say about their industrial capacity? And if they were doing this casually as a matter of

routine troop support rather than strategic necessity, what did that reveal about the depth of their resources? These questions haunted Japanese soldiers as the war progressed and the situation deteriorated. By 1943, American forces were advancing steadily across the Pacific, island by island.

Each campaign demonstrating industrial and logistical capabilities that Japanese planners had believed impossible. And every night the music continued, the signal never weakening. Glenn Miller’s orchestra playing on, a constant reminder that somewhere across the ocean was a nation untouched by bombing.

Its factories running at full capacity, its people fed and entertained, its military supplied with everything from ammunition to orchestras. Some Japanese soldiers tried to dismiss it. The music was propaganda, they told themselves, a trick to undermine morale. But this explanation grew harder to maintain as physical evidence accumulated. American prisoners of war, when captured, were found to be in better physical condition than their capttors, despite the hardships of combat.

American supply drops, when intercepted, contained not just ammunition and medicine, but cigarettes, candy, magazines, sometimes even photograph records. The abundance was real, not propaganda, and it was overwhelming. Corporal Tanaka listening to In the Mood in his jungle outpost in January 1942 could not have known what the next three years would bring.

He could not have predicted Midway or Guadal Canal or the island hopping campaign or the systematic destruction of Japanese naval and air power or the firebombing of cities or the final nuclear punctuation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But in that moment, listening to the impossible clarity of Glenn Miller’s brass section, something shifted in his understanding.

He had been told he was fighting for a just cause, for the liberation of Asia from Western colonialism, for the survival and expansion of the Japanese Empire. He had been told that Japanese discipline and spirit would overcome American material advantage. But the music whispered a different truth. That this was a war Japan could not win because it was fighting an enemy with resources beyond imagination.

An enemy so rich it could afford to swing. The psychological impact of American music on Axis forces was documented extensively, though often indirectly in intelligence reports and prisoner interrogations. After the war, occupying forces in Japan conducted thousands of interviews with former soldiers and the subject of American radio broadcasts appeared with surprising frequency.

A 1946 Army intelligence report declassified decades later summarized findings from interrogations of former Japanese radio operators. A consistent theme emerges regarding exposure to American entertainment broadcasts. Subjects report that the quality and consistency of American radio programming, particularly music broadcasts, contributed to a sense of enemy material superiority that contradicted official Japanese assessments.

Multiple subjects described American broadcast capability as proof of industrial capacity exceeding Japanese intelligence estimates. The report includes specific testimonies. A former Imperial Navy communication specialist stationed in the Philippines recalled, “We monitored American frequencies as part of our duties, and their music programs never stopped.

Even when we knew their forces were engaged in heavy combat, even during their own Christmas and holidays, the music played continuously. Our commanders told us the Americans were exhausted, that their economy was strained.” But the radio signals told a different story. A nation under strain does not broadcast music in perfect clarity every hour of every day.

Another testimony from a former army lieutenant who served in Burma. I began to understand we would lose the war not from battle reports but from listening to American radio. The variety of their programming, the number of different orchestras, the fact that they had musicians in uniform forming bands. This was the behavior of a nation with excess. We could not spare men for music.

We could barely spare men for essential production. But they had so many men, so much material that they could afford military bands. This was when I knew. These accounts reveal something crucial about the psychology of prolonged warfare. Morale depends not just on immediate circumstances, but on the belief that victory is possible, that sacrifices are leading somewhere, that the cause can ultimately triumph.

Japanese military culture had prepared soldiers to endure tremendous hardship, to accept death without question, to fight against overwhelming odds. But it had not prepared them for the cognitive dissonance of facing an enemy whose casual expressions of abundance contradicted everything they had been taught about western decadence and decline.

Glenn Miller’s music in this context functioned as accidental propaganda more effective than any carefully crafted message could have been. It was not trying to convince anyone of anything. It was simply American culture exported via radio waves reaching ears that were never supposed to hear it. And because it was authentic rather than constructed, because it was entertainment rather than persuasion, it carried a credibility that official propaganda could never achieve.

The numbers tell part of the story. By 1943, the Armed Forces Radio Service was operating more than 60 stations worldwide, broadcasting in multiple languages to both American troops and foreign audiences. The flagship station in Los Angeles transmitted at 50,000 watts, powerful enough to be heard clearly across the Pacific.

Programming included not just music, but news, comedy shows, dramatic programs, sports coverage, a full schedule of content that demonstrated the depth of American cultural production. Glenn Miller’s Army Air Force Band performed live broadcasts regularly, and recordings of his civilian orchestra were played constantly. The sheer volume of content was itself a statement of power.

But beyond numbers, it was the emotional character of the music that had impact. Big Band Swing was the sound of optimism. Its rhythms were driving, propulsive, forward moving. Its harmonies were bright, major key, consonant. Even slower ballads had an underlying confidence, a sense that romance and beauty would survive the war.

This was music that fundamentally believed in the future, in possibility, in the continuation of joy despite present circumstances. And for Japanese soldiers, many of whom were by 1943 and 1944 facing starvation, disease, isolation, and the certainty of defeat. This optimism was almost unbearable to hear.

Japanese soldiers entered the war with specific expectations carefully cultivated by years of propaganda and military indoctrination. They expected to face an enemy weakened by individualism, by racial division, by the supposed softness of democratic society. They expected that Japanese spiritual strength, Yamato Damashi, the spirit of Japan, would compensate for any material disadvantages.

They expected that the Western powers focused on the European theater would be unable to mount effective resistance in Asia and the Pacific. They expected in short a short war followed by negotiated peace that would leave Japan dominant in East Asia. What they experienced instead was an enemy of seemingly inexhaustible resources capable of fighting globally on multiple fronts without apparent strain.

They experienced American firepower that dwarfed anything they had encountered. Naval forces that grew stronger even as Japan shrunk air superiority that became absolute supply chains that functioned with machine-like efficiency even across thousands of miles of ocean.

And threading through all of this almost as a soundtrack to their disillusionment was American music playing constantly, never stopping. A reminder that somewhere beyond the combat zone was a nation functioning normally, producing not just weapons, but culture, not just surviving, but thriving. The contrast was especially stark for soldiers who had been stationed in China before the Pacific War.

There, Japanese forces had faced an enemy that was often poorly equipped, operating with limited industrial support, constrained by poverty and political division. Victory had seemed inevitable, a matter of superior organization and equipment. The transition to fighting American forces was shock on every level.

American soldiers were wellfed, wellarmed, supported by logistics networks of stunning efficiency. American tactics emphasized firepower over manpower, using industrial advantages to minimize casualties. American wounded received medical care that Japanese soldiers could only dream of. Battlefield hospitals with surgical facilities, blood transfusions, antibiotics, medevac, by air or sea.

The gap between the two military systems was so vast it seemed almost metaphysical. And yet, despite this overwhelming material superiority, American soldiers did not display the fanaticism or desperation that Japanese forces associated with existential struggle. They seemed, if anything, casual about the war, confident, but not desperate, determined, but not suicidal.

They advanced methodically rather than recklessly. They valued survival and appeared to expect to go home when the war ended. This attitude, so foreign to Japanese military culture, was perhaps most clearly expressed in their music. Glenn Miller’s arrangements were tight, disciplined, precise, but within that structure was an element of play, of improvisation, of joy.

The music said, “We are serious about winning, but we are not sacrificing our humanity to do it.” For Japanese soldiers taught that victory required total self-abnigation. This was almost incomprehensible. How could an enemy so casual about suffering be so effective at inflicting it? How could a military that allowed its soldiers to listen to swing music be so disciplined in combat? The contradiction forced a reconsideration of basic assumptions.

Perhaps American material superiority was not a sign of spiritual weakness, but simply an advantage that no amount of Bushidto could overcome. Perhaps the war was not, as propaganda claimed, a spiritual contest that Japan could win through superior will, but a material contest that Japan had already lost.

These thoughts were dangerous, even treasonous by the standards of Japanese military culture, but they were increasingly common as the war ground on and conditions deteriorated. Letters home when they mentioned American broadcasts at all did so elliptically with careful language that sensors might miss, but the meaning was clear. The enemy has many resources became a common euphemism.

Their supply lines are well-maintained meant we are starving and they are not. They continue to broadcast regularly meant they are not struggling the way we are. The music became a code for expressing doubts that could not be spoken openly. The psychological transformation that occurred in soldiers like Corporal Tanaka was gradual, cumulative, never the result of a single moment.

But music provided a consistent thread, a recurring reminder of uncomfortable truths. Each time a Japanese radio operator scanned frequencies and encountered American broadcasts, each time a soldier stationed near a monitoring post heard the sound of swing music drifting through the night. The message was reinforced. The enemy was not weakening, not struggling, not approaching the point of collapse that Japanese strategy depended on.

By 1944, the situation had deteriorated to the point that some Japanese units were explicitly forbidden from listening to American radio broadcasts except for intelligence purposes with officers enforcing the ban strictly. This prohibition was itself an admission of the music’s power.

If it were merely propaganda, merely enemy noise, there would be no need for bands. But military authorities recognized that American broadcasts were undermining morale precisely because they were not lies, not exaggerations, but authentic expressions of a culture and economy that Japan could not match. The transformation was not uniform. Some soldiers clung to official narratives until the end.

true believers who interpreted every setback as temporary, every sacrifice as necessary for eventual victory. But for many others, the accumulation of evidence in the form of lost battles, shrinking supplies, abandoned positions, and yes, the continuous presence of the American radio music led to a quiet internal shift. They continued to fight because discipline and honor demanded it.

Because surrender was culturally unthinkable, because the alternative was court marshall or execution. But belief in victory eroded, replaced by grim determination or fatalistic acceptance. In some cases, this transformation led to small acts of resistance. Soldiers who accidentally destroyed equipment rather than let it be used in suicidal attacks.

radio operators who passed intelligence to Philippine resistance networks knowing the information would reach American forces. PWS who cooperated with interrogators more readily than cultural norms suggested they should. These were not dramatic defections or public refusals, but quiet acknowledgments that the cause was lost, that survival had value, that perhaps the American enemy was not the monster propaganda had painted.

And what did they remember after the war? Decades later, when historians and researchers interviewed Japanese veterans, the subject of American music came up with striking regularity. A naval officer recalled listening to Glenn Miller on a submarine that had surfaced at night to recharge batteries. That music stays with you. Even now, when I hear those big band sounds, I am transported back to that submarine, to the dark water, to the moment I understood we were going to lose. A former sergeant remembered American broadcasts heard in a P camp

after surrender. They played the music for us, the guards. They wanted us to hear it and we understood what they were telling us. This is what you were fighting. This abundance, this confidence, this power. You never had a chance. These memories are tinged with melancholy with the complicated emotions of defeat and survival.

But they are also in their way tributes to the power of music as cultural communication. Glenn Miller probably never imagined that his arrangements would function as psychological warfare. He was simply trying to maintain morale among American troops to bring a piece of home to soldiers far from everything familiar. But in doing so, he inadvertently created something more powerful than propaganda.

authentic cultural expression that revealed truths about American society and industrial capacity that no amount of official messaging could convey. To fully understand the impact of American music on enemy morale, we must examine the industrial and logistical systems that made that music possible.

The armed forces radio service was not a small operation or a propaganda afterthought. It was a massive coordinated effort involving thousands of personnel, millions of dollars of equipment, and a supply chain that stretched across the globe. The fact that it functioned smoothly throughout the war, even as combat operations intensified, was itself a demonstration of American organizational capacity. Consider the production chain.

Musicians had to be recruited, trained, if necessary, and formed into bands. Instruments had to be manufactured, maintained, and replaced when damaged or lost. Recording equipment had to be produced and shipped to locations worldwide. Radio transmitters, some of the most powerful ever built, had to be constructed and supplied with electricity, which meant generators, fuel, and maintenance crews. Broadcasting studios had to be established and staffed.

Programs had to be planned, recorded, and transmitted on schedule. And all of this had to happen not just once, but continuously day after day, year after year, across dozens of locations from Alaska to Australia to North Africa. The resource commitment was staggering. Each broadcast station required electrical power equivalent to a small town.

The transmitters consumed fuel at rates that Japanese logistics officers would have considered unconscionable for anything other than essential combat operations. The personnel involved, radio technicians, engineers, announcers, musicians, support staff, numbered in the thousands, all of whom could theoretically have been assigned to combat roles or factory work instead.

But America could afford it. That was the point. Though the point was never explicitly stated, the very existence of the armed forces radio service was a message. We have so much industrial capacity, so much electrical power, so many trained personnel, so much logistical capability that we can devote substantial resources to entertainment without compromising our war effort in any way.

Japanese intelligence services monitored these broadcasts and prepared reports on their strategic implications. A translated intelligence assessment from 1943 captured after the war notes enemy radio broadcasts continue to expand in power and geographic reach. This suggests no degradation in American industrial capacity despite official propaganda regarding economic strain of two-front war.

Radio broadcasting infrastructure requires substantial electrical power, specialized manufacturing and trained personnel. Enemy ability to maintain and expand entertainment broadcasting while simultaneously increasing military production indicates resource depth far greater than previously estimated.

Strategic implications require reassessment. This dry military language conceals what must have been profound anxiety among Japanese planners. The initial strategy for the Pacific War had been based on calculations of American industrial capacity and political will. The assumption was that Japan could seize resourcerich territories, establish a defensive perimeter, and inflict enough casualties that America would agree to a negotiated peace rather than bear the cost of total victory.

This strategy required that America’s resources be finite, that its industrial capacity be strained by global commitments, that its democratic system would produce warw weariness and political pressure to compromise. But the radio broadcasts suggested something terrifying. That American resources were for practical purposes unlimited.

that the nation could fight a total war on multiple continents while maintaining civilian morale through entertainment. That there was no realistic hope of exhausting or outlasting such an enemy. Glenn Miller’s band in this context was not just entertainment but evidence. The Army Air Force Band included 50 musicians, all in uniform, all drawing military pay, all requiring transportation, housing, instruments, and support.

The band toured actively, performing live for troops across England, and eventually after Miller’s death in December 1944, continuing operations under new leadership. The music they played was arranged specifically for military bands with parts written for the instruments available with tempos and styles chosen to maximize morale effect.

This was not accidental or improvised. It was systematic, organized, resourced, and executed with the same attention to detail that characterized American military operations generally. And the music itself reflected industrial sophistication. The recordings that Japanese soldiers heard were produced in professional studios using cuttingedge equipment.

The sound quality was far superior to anything Japanese recording technology could achieve. Sharper, clearer, with better frequency response and less distortion. The difference was audible even through the static of shortwave reception. American music sounded modern. technological advanced. It sounded, in other words, like the product of a more developed industrial civilization, which it was.

This technological gap extended to every aspect of war making. American ships had better radar, better fire control systems, better engines. American aircraft had better instruments, better radios, better metallurgy. American tanks had better optics, better armor, better transmissions. And yes, American music had better recording, better transmission, better fidelity. The pattern was consistent across domains.

America did not just have more resources. It used those resources more effectively with greater technological sophistication backed by an industrial system that could innovate and mass-produce simultaneously. For Japanese soldiers who had been raised on propaganda about Western decadence and Asian resurgence, this was bitter medicine.

The war was supposed to demonstrate Japanese superiority, the vitality of the Yamato spirit, the power of will over material. Instead, it was demonstrating the opposite. That industrial capacity mattered more than ideology. That technology could not be overcome by determination alone. that in total war between industrialized nations, the side with more factories, more resources, and more efficient production would inevitably prevail.

Regardless of spiritual narratives, the music itself carried messages beyond mere presence or quality. The structure of big band swing, the way it was organized and performed, reflected cultural values that were distinctly American and distinctly foreign to Japanese military culture. To understand this, we must listen to the music the way enemy soldiers might have heard it as cultural text rather than mere entertainment.

Big band arrangements were complex, but their complexity was different from the rigid hierarchies of military music or the formal structures of classical composition. A typical Glenn Miller piece featured multiple sections working in coordination. saxophones providing melodic lines, brass punctuating with sharp bursts, rhythm section maintaining steady pulse. But within this structure was constant variation.

Soloists stepped forward to improvise, taking liberties with melody and rhythm while the band supported them. Then the soloist would step back and another would take a turn or the full ensemble would return to the arranged material. The effect was both disciplined and loose, controlled and free, collective and individual simultaneously.

This musical structure was, whether intentionally or not, a sonic metaphor for American society. Democratic in the sense that different voices took turns, that individual expression was celebrated within collective effort, that there was room for innovation within tradition. The improvisation that was central to jazz and swing had no real parallel in Japanese music.

Traditional Japanese forms were highly codified with established patterns and minimal deviation. Even western classical music which had been adopted by Japanese cultural institutions was performed with emphasis on precise reproduction of the written score. But swing encouraged, even required, individual interpretation, spontaneous creativity, deviation from the written arrangement.

Japanese soldiers listening to this music may not have consciously analyzed its structural implications, but the difference was palpable. This was music that celebrated individual personality while maintaining group cohesion. music that could be technically precise and emotionally spontaneous at the same time.

Music that sounded confident because it emerged from a culture that was confident in its values, its systems, its place in the world. Contrast this with Japanese military music, which emphasized unison, uniformity, synchronization. March tempos were strict, unvarying. Melodies were simple and repetitive, designed to support group movement rather than individual expression.

The aesthetic was collectivist in the most literal sense. Everyone doing exactly the same thing at exactly the same time. Individual differences submerged into group identity. This approach to music reflected and reinforced the broader cultural emphasis on subordination of self to group, on obedience to hierarchy, on the suppression of individual will in service of collective goals.

Neither approach to music is inherently superior. They reflect different cultural values and serve different purposes. But in the context of industrial warfare, the cultural values encoded in American music proved more adaptive. A military culture that could balance individual initiative with collective discipline that encouraged problem solving and adaptation that allowed for flexibility within structure was better suited to modern combined arms warfare than a system that prioritized obedience over initiative. And soldiers who heard the music could

sense this even if they could not articulate it. The sound of American confidence was not bravado or bluster. It was the confidence of a system that worked, of a culture that produced both innovative individuals and effective organizations, of a society that could be loose and tight, playful and serious simultaneously.

As the war progressed and Japanese military fortunes declined, the presence of American radio broadcasts became increasingly painful. By mid 1944, Japan had lost control of the central Pacific. The Philippines were under assault, and the home islands were beginning to experience regular air raids. Supplies to isolated garrisons dwindled to nothing.

Soldiers on bypassed islands faced slow starvation, disease, and the knowledge that no relief was coming. And through it all, the American music played. There is something almost cruel about this, though the cruelty was unintentional. American broadcasters were not trying to torment enemy soldiers.

They were simply maintaining programming for American troops, doing their job, keeping morale high among their own forces. But for Japanese soldiers, listening on islands that had been cut off and forgotten, hearing Glenn Miller’s orchestra swing through another cheerful arrangement was a form of psychological torture. It was a reminder that while they were dying slowly of malnutrition and tropical diseases, the enemy was supplied, supported, entertained.

That while Japanese supply ships lay at the bottom of the ocean and aircraft sat grounded for lack of fuel, American logistics functioned so smoothly that they could afford to broadcast music continuously. One captured diary found on Guadal Canal after the Japanese evacuation includes this entry from late 1943. We have not received supplies in 6 weeks. The rice is gone.

We eat roots and insects. At night, I hear American music from across the water. Their camp must be close. The music is clear and bright. They have electricity for this. We have nothing. I wonder if I will survive to hear such music again or if I will die here listening to the enemy’s joy. The writer did not survive.

His body was found near the diary dead of dysentery and malnutrition. But his words capture something essential about the experience of Japanese soldiers in the latter stages of the Pacific War. The grinding despair of fighting a hopeless battle against an enemy with unlimited resources symbolized by something as simple and devastating as music that never stopped.

In the Philippines during the brutal fighting of 1944 to 1945, American forces sometimes used loudspeakers to broadcast music and messages toward Japanese positions. This was explicit psychological warfare designed to encourage surrender. The music was often big band swing, including Glenn Miller’s recordings. The message was wordless but clear.

You are surrounded by an enemy so powerful that they can afford to play music while they destroy you. Surrender now and you will be treated well. Continue fighting and you will die for no purpose. Japanese military culture made surrender nearly unthinkable for most soldiers, but as conditions became desperate, some did give up. Interviews with these prisoners revealed that the music had played a role in their decisions.

One sergeant explained, “I could accept death in battle. I was prepared for that, but dying slowly of hunger while hearing the enemy’s music every night, this seemed like dying for nothing.” The music told me the war was already over, that my death would change nothing. So I chose to live instead.

If we return to our central symbol, the radio, the means by which this music reached enemy ears, we can see how it accumulated meaning throughout the war. At the beginning in 1942, the radio represented curiosity, surprise, a glimpse into enemy culture. By 1943, it represented evidence, proof of American industrial capacity. By 1944, it represented despair, a reminder of the vast gulf between the two nations capabilities.

And by 1945, as the war approached its conclusion, the radio represented inevitability, the sound of victory already achieved. But the radio was not just a receiver of messages from outside. It was also for many Japanese soldiers a lifeline to sanity, to humanity, to something beyond the horror of their immediate circumstances.

Music, even enemy music, provided a temporary escape from hunger, fear, and death. Some soldiers came to depend on the American broadcasts, tuning in despite orders not to, because the music reminded them that there was a world beyond the war, that beauty and joy still existed. somewhere even if not where they were.

This created profound internal conflict. How could you hate an enemy whose music moved you? How could you maintain fighting spirit against a nation whose cultural productions you had come to appreciate? Japanese military ideology provided no framework for this kind of complexity. The enemy was supposed to be barbaric, inferior, contemptable.

But the reality was far more complicated. American culture, as expressed through its music, was sophisticated, appealing, emotionally resonant. It was not the culture of barbarians. It was the culture of a civilization that had, in critical ways, surpassed Japan’s own.

This realization was devastating for soldiers who had built their identity around belief in Japanese cultural superiority. The greater East Asia co-rossperity sphere had been justified in part as a mission to liberate Asia from Western domination and spread Japanese civilization as the superior alternative.

But if Japanese civilization could not even match Western civilization in music production and broadcast technology, how could it claim superiority in broader cultural or political terms? The music became a crack in the ideological edifice and once that crack appeared it was impossible to unsee. After the war during the American occupation of Japan, Glenn Miller’s music became popular among Japanese civilians played on radio stations that were now controlled by occupation authorities. There is a bitter irony in this.

The music that had symbolized American power during the war became after the war simply popular entertainment. Enjoyed without the context of conflict. But for veterans who heard it, the music always carried additional weight. It was never just music. It was the sound of a lost war, of a world transformed, of the moment they understood that everything they had been told was wrong.

On December 15th, 1944, Major Glenn Miller boarded a small aircraft in England, bound for Paris, where his band was scheduled to perform for troops who had just liberated the city. The aircraft disappeared over the English Channel, likely due to weather or mechanical failure, and Miller’s body was never recovered.

He was 40 years old and at the height of his influence and popularity. The loss was mourned deeply in America, a reminder that even those serving in support roles far from front lines were not immune to the dangers of war. But the music continued. The Army Air Force Band kept performing under new leadership. Miller’s civilian recordings continued to be broadcast.

The sound that had become synonymous with American presence in the war did not fade with his death. If anything, it took on additional resonance, a tribute to a man who had voluntarily given up commercial success to serve his country and who had died in that service.

For Japanese soldiers who had listened to Miller’s music throughout the war, his death, when they learned of it, which many did not until after the war ended, carried symbolic weight. Even the man himself had been sacrificed, had become one more casualty in the vast machinery of the war. But his music outlived him, continued to broadcast, continued to represent American presence and power.

This seemed fitting in a way. The music had never really been about Glenn Miller, the individual, despite his fame. It had been about what his music represented, the industrial and cultural capacity of a nation that could produce such sounds and broadcast them across the world while simultaneously producing tanks, ships, aircraft, and all the material of war in quantities that seemed impossible. The war ended 9 months after Miller’s death.

Japan surrendered on August 15th, 1945 after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Manuria made further resistance meaningless. For Japanese soldiers who survived, the surrender brought complex emotions, relief that the dying was over, shame at defeat, uncertainty about the future. But for many, the surrender was not entirely surprising. They had heard it coming in a sense for years.

Every night in the sound of Glenn Miller’s orchestra swinging through another arrangement, they had heard the truth that propaganda tried to conceal that they were fighting a war they could not win against an enemy they could not match. There is a photograph taken in Tokyo in 1946 of Japanese civilians gathered around a radio in a public square listening to a broadcast from American occupation authorities.

The radio is new, Americanmade, part of the reconstruction aid flowing into the country. The music playing is big band swing. The people listening show varied expressions, some smiling, some contemplative, some blank with exhaustion and trauma. But they are listening. This image captures something essential about the transformation that the war brought.

Japan had entered the conflict believing in its own destiny, its spiritual superiority, its rightful place as leader of a new Asian order. It had emerged defeated, occupied, its cities destroyed, its economy shattered, its ideology discredited. And yet in the ruins there was something new.

the possibility of rebuilding along different lines, of learning from defeat, of absorbing lessons that victory would never have taught. The music that had been psychological warfare during the war became cultural diplomacy after it. American jazz and swing became hugely popular in post-war Japan, part of a broader embrace of American popular culture that reshaped Japanese society.

The generation that had fought against America became the generation that rebuilt Japan as an American ally. And their children grew up listening to music that their parents had once heard as the sound of the enemy. But the deeper legacy of that music of those radio broadcasts that reached across the Pacific during the darkest years of the war is about the power of culture to communicate truths that propaganda cannot obscure.

Glenn Miller probably never intended his music to function as strategic weapon. He was an entertainer, a musician who believed in using his talents to support the war effort. But in the act of doing what he did best, creating music that captured the energy and optimism of his time, he inadvertently created something more powerful than bullets or bombs.

Authentic cultural expression that revealed the true nature of American industrial democracy. for Japanese soldiers listening in their jungle outposts and island garrisons that music told truths they were not supposed to know. It told them that America was not weak, not divided, not on the verge of collapse.

It told them that American society could fight a total war while maintaining cultural production, civilian morale, and democratic norms. It told them that material resources mattered more than spiritual narratives, that industrial capacity could not be overcome by willpower alone, that in the contest between abundance and scarcity, abundance would prevail.

These were hard truths paid for in blood and suffering by millions on both sides of the conflict. But they were truths nonetheless. And music carried them more effectively than any propaganda broadcast could have done. Because music is not argument or evidence or rhetoric. Music simply is. You cannot debate it or dismiss it or reason it away. You can only hear it and feel what it makes you feel and understand what it reveals about the people who made it.

And what Glenn Miller’s music revealed was a nation confident enough to swing even in the midst of the worst war in human history. A nation with resources so deep it could afford orchestras and uniform. A nation that believed not just in victory, but in joy, in beauty, in the possibility that life could and should be more than mere survival.

This was the America that Japanese soldiers heard through their radios. And this was the America that in the end they could not defeat. The music played on even after the last shot was fired, even after the surrender documents were signed, even after the world had changed forever.

It plays still in recordings preserved and remastered in archives and radio stations and streaming services. A permanent record of a moment when sound carried the weight of history. When you listen to Glenn Miller now, you hear what Japanese soldiers heard then. Not just notes and rhythms, but the sonic signature of a civilization at the height of its power, confident in its strength, assured of its victory, swinging its way through a war that would reshape the world.

That is what music can do. It can cross oceans and penetrate defenses. It can carry messages that no other medium can convey. It can reveal truths about nations and cultures and moments in time. And it can remain long after the war is over as testimony to what was fought for, what was lost, and what in the endured.

Somewhere in the static between stations, in the empty frequencies where wartime broadcasts once traveled, the echo remains. The sound of brass and saxophone, of drums keeping time, of melodies that captured an era and a people and a cause. The sound of America at war, making music while making history, swinging while the world burned and rebuilt.

The sound that Japanese soldiers heard and understood too late what it meant. The sound of abundance. The sound of democracy. The sound that crossed an ocean and changed everything it touched. The sound of Glenn Miller playing on.

News

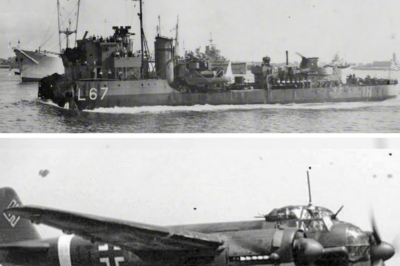

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

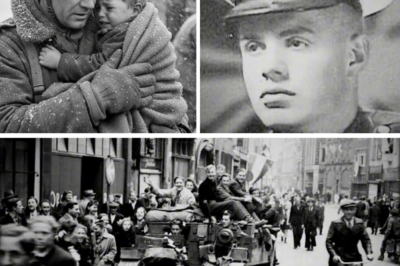

CH2 The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days Most people have no idea that one…

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

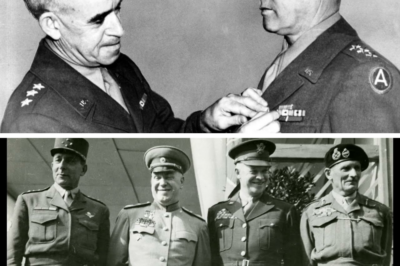

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size At…

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

End of content

No more pages to load