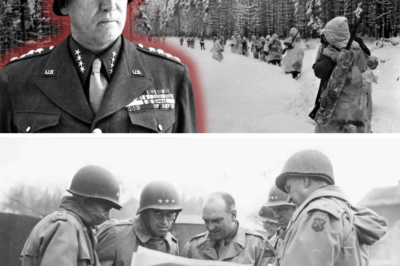

How George Patton Earned The Nickname “The Blood And Steel General,” – And Became The Most Feared General By The N@zis

Few names in American military history carry the same weight, admiration, and controversy as General George Smith Patton Jr. To his enemies, he was “the American panzer commander,” a relentless, unpredictable force whose very name became synonymous with momentum and destruction. To his soldiers, he was both a hero and a tyrant—a leader who demanded everything but who also made them believe they could do the impossible. To the Germans, he was “der Blut und Stahl General”—the General of Blood and Steel. His reputation preceded him across every battlefield he touched, and wherever he appeared, the front shifted. Lines that had held firm for months crumbled. The enemy didn’t just prepare for battle; they prepared for Patton.

But long before he became the most feared general in the European theater, George Patton was simply a boy with an impossible dream and a history he could never quite escape. He was born on November 11, 1885, at the family’s sprawling Lake Vineyard Ranch in San Gabriel, California, into a world steeped in military tradition. The Pattons were not merely soldiers by occupation—they were soldiers by blood. The family’s legacy ran deep through the veins of American history. His great-grandfather, Hugh Mercer, had served under George Washington and died a hero’s death at the Battle of Princeton during the American Revolution. His grandfather, George Smith Patton Sr., had been a Confederate colonel who fell at Winchester during the Civil War, and another relative, Waller Tazewell Patton, was killed at Gettysburg. The Pattons’ story was one of gallantry and tragedy, a lineage of men who fought, bled, and died in uniform.

Growing up in such a household meant that young George’s destiny was never really in question. His father, George Smith Patton Sr., was a lawyer and rancher, but his mind often drifted back to the glories of the old Confederacy. The walls of the family home were adorned with sabers, portraits, and relics of bygone wars. Dinner conversations were filled with tales of courage, sacrifice, and honor. The message was clear: a Patton was born to fight.

Yet beneath the romantic image of the Southern warrior heritage lay a boy struggling with something deeply human. Patton was dyslexic, a condition not yet understood at the time, and it made reading and writing a daily torment. While other children breezed through their lessons, George labored over every word, every line. His parents, unwilling to let him fall behind, hired private tutors and filled his days with study, drilling discipline into him as firmly as any military instructor ever would. He wouldn’t attend a traditional school until age eleven.

But what he lacked in academics, he made up for with passion, energy, and sheer determination. From an early age, he developed an obsession with history, particularly the great commanders of antiquity. While most boys his age were chasing frogs or playing games, George was memorizing the campaigns of Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, and Napoleon Bonaparte. He could recount every maneuver of Hannibal’s march across the Alps and every battle of the Roman legions. He saw these men not as distant historical figures but as mentors—teachers from across time, whispering the secrets of warfare.

He carried with him the conviction that greatness was not a matter of chance but of preparation and will. “You must be born a soldier,” he once wrote in a letter as a young man, “but you must also train to become a great one.” That philosophy would shape the rest of his life.

Alongside his fascination with history came a deep love for the heroic ideals of ancient literature. He devoured Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, seeing in their verses reflections of the kind of glory he longed to achieve. To him, Achilles and Odysseus weren’t mythical relics—they were blueprints for leadership, for bravery, for destiny. The romanticism of battle filled his imagination. He wasn’t blind to its horrors, but he believed in its necessity—the crucible through which true character was forged.

Physically, Patton was tall, strong, and exceptionally athletic. He threw himself into every sport he could find, as if preparing his body for the demands of war before he’d ever seen a battlefield. He excelled at fencing, polo, swimming, and horseback riding. The latter became an obsession. Horses represented freedom, power, and control—qualities that resonated with him deeply. His ability in the saddle would later define much of his early military career, when the cavalry was still seen as the noblest branch of service.

In 1902, at just sixteen, he made his first bold move toward that destiny. He wrote directly to Senator Thomas Bard of California, asking for a recommendation to the United States Military Academy at West Point. His letter was passionate, almost defiant, the words of a young man who already believed he was meant for something larger than life. But the response was a blow—his application was denied. His grades in mathematics weren’t good enough, and his reputation for being headstrong made some question whether he was suited for the academy’s rigid discipline.

Patton refused to let that stop him. Instead, he enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute, determined to prove himself worthy of a second chance. At VMI, he thrived. The school’s emphasis on discipline, routine, and physical rigor suited him perfectly. He was up before dawn every day, drilling, studying, and pushing himself past exhaustion. His instructors noticed something different about him—a natural command presence that set him apart even among ambitious cadets. He wasn’t the most gifted student, but he had an intensity, a fire that drew others to him.

In 1904, his persistence paid off. After a year at VMI, he finally earned an appointment to West Point. To most cadets, West Point was a stepping stone. To Patton, it was sacred ground. He threw himself into his training with single-minded determination, though the academic challenges that had plagued him since childhood followed him still. His dyslexia made technical subjects difficult, and his grades often hovered dangerously close to failure. But in the gym, the fencing hall, and the equestrian ring, he was unmatched.

Patton approached fencing with the same obsession he brought to everything else. He studied the art as if it were war in miniature—every movement a battle between life and death, every parry and strike a lesson in courage. He became one of the best swordsmen at West Point, and his mastery of the blade would later earn him a spot on the U.S. Olympic fencing team.

But it wasn’t just physical excellence that defined him. Even in his early years as a cadet, Patton began developing the fierce leadership style that would make him legendary—and notorious. He demanded perfection from himself and from everyone around him. He despised laziness and cowardice. To his classmates, he could seem arrogant and relentless, but when drills began and the pressure mounted, they found themselves following his lead instinctively. He had that rare gift of command that couldn’t be taught—an ability to make others believe, if only for a moment, that failure was impossible.

Still, his time at West Point was far from smooth. He accumulated demerits for infractions—fighting, insubordination, and an infamous incident where he nearly struck an upperclassman who insulted him. He chafed under authority but never broke under it. When he graduated in 1909, he ranked 46th in a class of 103—not outstanding, but more than enough to earn him a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Cavalry.

By the time he pinned on his gold bars, Patton’s reputation had already begun to precede him. His instructors described him as “impatient, impetuous, and fearless,” a man with “unlimited potential if properly harnessed.” His peers called him “old blood and guts” even then—half as a joke, half as an acknowledgment that beneath the polished exterior beat the heart of a warrior from another age.

Everything about him seemed to belong to a different time. He quoted Caesar and Napoleon more readily than his own commanding officers. He saw war not as an aberration but as the natural state of man—a stage upon which courage, discipline, and genius could shine. To him, peace was simply the interval between the tests that defined greatness.

In the years that followed, those ideals would collide with the brutal reality of modern warfare. He would trade the cavalry’s horse for a tank, his saber for steel treads, and his romantic visions for mechanized destruction. But that transformation—the making of the man who would terrify the N@zis across two continents—was still ahead.

For now, in the quiet years before the storm, George S. Patton Jr. stood on the threshold of the twentieth century, a young officer with an old soul, shaped by family ghosts, ancient heroes, and an unshakable conviction that destiny had chosen him for war.

Continue below

Few military figures of the Second World War aroused so much admiration and so much controversy as George Smith Patton. The Germans knew him as the general of blood and steel. His style was explosive, direct, without concessions. Wherever Patton appeared, the front changed, his troops advanced without rest, and his name alone was enough to instill respect and fear.

While other commanders carefully planned each movement, Patton bet on speed, surprise, and aggressiveness. He believed that the war had to be won by attacking, always attacking. And that philosophy made him one of the most feared generals by the Third Reich. But who really was this man behind the uniform? A military genius ahead of his time or a reckless leader dominated by his temperament.

Today we will explore the life, the victories, and the shadows of the general whom the N@zis never underestimated. George Patton, the most feared general by the N@zis. George Smith Patton Jr. was born on the 11th of November of 1,885 at the Lake Vineyard Ranch located in San Gabriel, California in the heart of a family deeply rooted in the military tradition.

Son of George Smith Patton and Ruth Wilson, from an early age, he was immersed in an environment that valued honor, discipline, and service to the nation. His lineage was marked by historical figures who left their mark on momentous conflicts. Among them was Hugh Mercer, an ancestor who during the War of Independence of the United States commanded a group of rebels in the Battle of Princeton in the year 1777 and fell in combat against the British Army.

In addition, during the Civil War, members of the family actively participated in the Confederate Army. His grandfather, George Smith Patton, led the 22nd Regiment of Virginia until he died in the Battle of Winchester, and Waller Taswell Patton fell at Gettysburg, consolidating a legacy of military service that undoubtedly influenced Patton’s upbringing.

Since childhood, Patton faced a significant personal challenge, dyslexia, which made his learning in reading and writing difficult. To overcome these difficulties, he received private instruction at home until the age of 11 when he finally entered the Steven Clark School in Pasadena. This period was crucial for the development of his character.

Despite the initial academic difficulties, he showed remarkable intelligence and an insatiable curiosity, especially in history and military strategy. During his adolescence, he became fascinated with the exploits of great strategists and leaders of history such as Scipio Africanis, Julius Caesar, Hannibal Barker, Joon of Arc, Napoleon Bonapart, and the Confederate John Mosby. His interest in these figures was not limited to admiration.

He studied their campaigns, tactics, and strategic decisions, developing a deep understanding of war, logistics, and leadership. Patton also found in classical literature and Grecom Roman mythology a refuge and a source of inspiration.

The Iliad and the Odyssey became his bedside books where the heroes and warriors of old shaped his conception of honor, bravery, and glory on the battlefield. Alongside his intellectual interest, he excelled in various sports, cultivating skills that would be essential for his future military career. Horsemanship, in particular, became one of his great strengths.

His mastery over the horse not only allowed him to stand out in sports competitions, but also gave him a crucial advantage in his training as a cavalry officer where mobility and control of terrain were fundamental. His military vocation manifested itself very early. In 1902, at only 16 years old, Patton wrote to Senator Thomas Bard requesting his admission to the Military Academy of the United States.

Although his first request was rejected due to his low performance in mathematics, his determination did not diminish. Seeking to fulfill his dream, he entered the Virginia Military Institute where he distinguished himself by his discipline, rigor, and competitive spirit.

There he was recognized for his leadership ability and his commitment to physical and academic training, which caught the attention of his instructors and trainers. In 1904, thanks to his outstanding performance, Patton managed to be admitted to the prestigious military academy of West Point, the institution that trained the most outstanding officers of the United States Army.

At West Point, Patton combined his academic training with intense physical and military preparation. He excelled in fencing, polo, and American football, sports in which he developed endurance, agility, and a strong sense of teamwork. During his time at the academy, he suffered several injuries, including fractures and flabitis, which only strengthened his resilience and determination.

His strict discipline and competitive character led him to graduate with honors as the first of his class in 1907, obtaining the rank of second lieutenant of cavalry, thus laying the foundations for a military career that would make him one of the most legendary generals of the United States. During his training at the Military Academy of West Point, Patton distinguished himself not only for his academic excellence, but also for his remarkable physical and athletic performance.

He practiced fencing, polo, and American football, disciplines that allowed him to develop discipline, endurance, and competitive spirit. American football in particular left him permanent scars. He suffered three broken noses and flabbitis. But these injuries only strengthened his character and his tenacity. Horsemanship was another of his great passions.

His ability to ride a horse not only made him an outstanding rider, but also prepared him for his future role as a cavalry officer where mobility and mastery of terrain were essential. Finally, in 1909, George Patton graduated from West Point as second left tenant of cavalry, crowning years of effort and strict training.

Parallel to his military life, Patton began to forge a stable personal life. During a vacation on Santa Catalina Island, he met Beatatrice Banning Ay, daughter of the influential Boston industrialist Frederick Ay. Their relationship soon consolidated and they married on the 26th of May of 1910 at the Beverly Farm in Massachusetts.

The couple had three children, Beatatrice Smith, Ruth Ellen, and George Patton IV, who would continue the family’s military legacy in later years. Patton managed to balance his family life with an intense military career, always maintaining a rigorous focus on his training and the development of his strategic and physical skills.

At the same time, Patton developed a highlevel sporting facet. He was selected to represent the United States in the Olympic Games of Stockholm of 1912, where he competed in the modern pentathlon, an event that combined fencing, swimming, pistol shooting, equestrianism, and cross-country running, facing 42 international rivals of great caliber.

His results were remarkable. He obtained third place in equestrianism, ninth in fencing, fifth in the 4,000 m flat race, and a disputed result in pistol shooting, a discipline in which he did not reach the podium due to controversies in scoring.

These competitions not only showed his physical versatility, but also his ability to maintain concentration and precision under pressure, qualities that would be decisive in his military career. Within the United States Army, Patton also received a particular recognition. He was named master of the sword, a title that consecrated him as a master in fencing.

And he designed the cavalry saber M1,913, later known as the patent saber. This weapon not only represented a technical advance in cavalry armorament, but also symbolized the innovation and perfectionism that would characterize his entire career. Thanks to his performance in the Olympic Games of 1912, he was again selected to participate in the Olympic Games of 1912,916 in Mexico City.

However, the celebration of these games was cancelled due to the Mexican Revolution and the activity of the guerilla leader Panchcho Villa whose uprising generated instability in the region. That same year, young Latutenant Patton returned to Mexico, but now in a strictly military context. He was part of the punitive expedition organized by the United States Army under the command of General John J.

Persing, an operation intended to capture or neutralize the forces of Panchcho Villa, responsible for the incursion in Columbus, New Mexico, and the killing of several American civilians. Patton joined the First Cavalry Regiment, and his first contact with real war was an experience that would mark his career. In May of 1916, he led a small unit of 10 soldiers in a direct assault on an enemy position where he confronted Villa’s fighters.

During the confrontation, Patton personally eliminated two guerillas, including Julio Cardinus, the chief of Villa’s personal guard, marking two notches on his ivory pistol that symbolized his first combat victories. This episode not only granted him immediate recognition within the army, but also allowed him to experience firsthand the dynamics of leadership in real combat situations, consolidating his reputation as a bold, determined officer willing to take calculated risks.

The first baptism of fire of George Patton came on the 14th of May of 1,916 in the framework of the punitive expedition against Panchcho Villa, a military operation that the United States launched in response to the attacks of the Vilista guerilla in New Mexico. Patton, then left tenant of the sixth infantry regiment, personally led a small detachment of 10 soldiers in a risky incursion on an enemy position.

For the time, his tactic was innovative. He used three automobiles as a means of transport and assault, an early form of mobility that contrasted with traditional movements on horseback. During the combat, Patton demonstrated uncommon audacity and personally shot several guerillas, among them Julio Cardinas, considered one of Villa’s main bodyguards.

This act not only consolidated his reputation as a brave and determined officer, but also marked the beginning of his custom of carving notches on the grip of his cult pistol to commemorate his victories, a habit he would maintain throughout his entire career. Informed of the episode, General John J. Persing could not avoid joking, “We have a true bandit in our ranks,” a comment that reflected both admiration and surprise at the daring of the young lieutenant.

With the entry of the United States into the First World War in April of 1917, Patton was transferred to France in June as part of the American Expeditionary Force once again under the command of Persing. His assignment was fundamental for the evolution of American mechanized warfare. He was entrusted with the command of the newly formed tank corps, weapons still experimental that Patton defended as the natural evolution of cavalry on the modern battlefield.

During his stay in Paris, he had the opportunity to study closely the French Reno FT, which had been employed successfully in the Battle of Cambre and which represented a crucial technological advance in the war. Between 1,917 and 1,918, Patton trained about 500 American crew members in handling the Reo FT, becoming the only American officer with practical experience in their operation before the first units arrived at the front.

His rigorous preparation included combat maneuvers, coordination exercises between vehicles and attack practices on enemy positions, developing procedures that would be the basis of American armored doctrine in the future. In August of 1918, already in command of the 304th Armored Brigade, he participated successfully in the battle of San Miguel, where American tanks broke German lines effectively and later in the Muse Argon offensive.

During this last operation, Patton suffered serious wounds on the 25th of September while trying to capture a hill independently alongside a sergeant in an act of daring that reflected his impulsive style and his willingness to take extreme risks. Barely a month later, the war ended and Patton received the Purple Heart in recognition of his valor and leadership.

Back in the United States in 1919, he was assigned to Camp Me, Maryland with the rank of captain serving as an instructor. There his reputation as a strict and demanding officer was consolidated. He imposed absolute discipline, tolerated not the slightest mistake, and expected formal treatment from his subordinates, showing his pride in his lineage and training.

For many recruits, his style was close to that of Prussian officers, which caused some to consider him an unbearable tyrant, although his authority and competence were indisputable. His formative influence left a deep mark on the soldiers who passed under his command, many of whom remembered his rigorous methods and his passion for perfection.

During the interwar period, Patton continued his professional and academic development teaching classes in different barracks, among them Fort Meer in 1,920 and the cavalry school of Fort Riley between 1,922 and 1,923. In these posts, he not only taught cavalry tactics and military leadership, but also began to develop and perfect concepts of mechanized warfare that would later be applied by the Allied armies in the Second World War.

His interest in modernizing cavalry and experimenting with new technologies was not limited to the academic field. Patton carried out studies on mobility, coordination of units, and the integration of armored vehicles in military strategy, laying the foundations of what would be known as American armored doctrine.

Beyond his strictly military work, George Patton achieved public notoriety for several episodes that showed his daring and determined character even outside the military field. In 1923, while enjoying a vacation on a luxurious yacht anchored in Salem, Massachusetts, Patton saved several children who were about to drown, throwing himself without hesitation into the water to rescue them.

Shortly afterward, he again appeared in the headlines when he thwarted the kidnapping of a woman. Armed only with his pistol, he confronted three men who were trying to take her by force, forcing them to flee. Both episodes consolidated the image of Patton as a bold and daring man capable of acting with speed and determination whether on the battlefield or in civilian life and reinforced the perception of his intrepid character among American public opinion.

In 1925, Patton was assigned to the Hawaiian Division based in the barracks of Honolulu where he assumed the responsibility of supervising the defense of the islands. During his inspection, he did not hesitate to describe the facilities and defensive preparation as poor and ineffective, warning of vulnerability to a possible foreign attack.

His warnings, ignored by the military bureaucracy, would prove prophetic almost two decades later with the devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which showed the serious shortcomings in American defense of the region. During his stay in Hawaii, Patton not only supervised fortifications and training, but also promoted the modernization of cavalry troops and the study of mechanized tactics, anticipating the transformation that the American army would experience toward armored warfare.

Between 1,927 and 1,931, Patton was assigned to the office of the chief of cavalry in Washington, DC, where he developed and consolidated his ideas on mechanized warfare. He was a firm defender that armored units should constitute a weapon independent of the infantry, an advanced vision for the time that anticipated the armored doctrine that the Allied armies would implement in the Second World War.

His work included studies on coordination between units, mobility, penetration tactics, and the integration of tanks in rapid maneuvers, elements that later would be decisive in the operations of his third army. In 1932, his career was involved in one of the most controversial episodes of his trajectory. Patton accompanied General Douglas MacArthur in command of 600 soldiers to disperse the bonus army, a group of First World War veterans who protested in Washington for the early payment of their pensions. Although most of these men were former comrades in

arms, Patton had to resort to the use of bayonets and tear gas to disperse the concentration, an action that left him deeply displeased and that provoked criticism inside and outside the army. This incident did not affect his career since in 1934 he was promoted to left tenant colonel and a year later assumed again the command of the Hawaiian division consolidating his influence on the reorganization of troops in the Pacific and the training of officers in modern combat tactics.

His career was also marked by personal challenges. In 1937, during a military maneuver exercise that sought to evaluate the mobility and coordination of his units, George Patton suffered a serious leg fracture that kept him temporarily away from active duties. The injury was a hard blow for the general, not only because of the interruption of his career, but also because of the physical limitation that prevented him from participating directly in the activities he valued so much. cavalry exercises, field inspections, and personal

supervision of the training of his troops. During his recovery, Patton used the time to deepen in military theory, study cavalry tactics manuals, and review the history of classic battles, analyzing movements, strategies, and decisions of commanders he admired from Hannibal to Napoleon, always with the intention of applying those lessons in future confrontations.

After recovering in 1938, Patton was named commander of the fifth cavalry regiment in Texas, already with the rank of general. This position offered him an ideal stage to experiment with the modernization of cavalry, anticipating the inevitable transition to motorized and armored units. He introduced maneuvers that combined mounted cavalry and motorized vehicles, evaluating speed of movement, coordination between sections, and the integration of light and heavy weapons.

He also promoted night trainings and logistics exercises in difficult terrain, aware that modern war would require both speed and adaptability to different environments and combat conditions. In addition, Patton began to take a strong interest in the use of mechanization to create fast units capable of carrying out penetration and flanking maneuvers, concepts that he would later apply masterfully in command of the American Third Army in Europe.

His approach included the physical and psychological preparation of his soldiers, insisting on strict discipline, active leadership, and rapid decision-making, principles he considered essential for success in a large-scale conflict. During this period, he also strengthened cooperation with other branches of the army, exploring coordination between infantry, artillery, and motorized units, as well as the integration of aviation in tactical support.

Patton understood that modern war could not be limited to traditional cavalry, nor to direct confrontation techniques, but rather required a combined approach in which mobility, surprise, and speed of execution were decisive. Thus, the time in Texas not only consolidated Patton’s reputation as a demanding and disciplined leader, but also allowed him to lay the conceptual and practical foundations that would later define his brilliant performance during the Second World War, from the liberation of Normandy to the dazzling campaign in Germany. His experience in the

transition from cavalry to mechanized units became a central element of his strategic thought, anticipating the armored warfare that would dominate the European battlefields. A few years later, Second World War. With the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe in 1939, George Patton was summoned by the Third Army of the United States to assume the crucial task of organizing and developing the future armored branch, a military component still incipient that he saw as the natural evolution of traditional cavalry. Patton’s vision was clear.

Tanks should not be mere companions of the infantry, but independent maneuver units capable of breaking enemy lines with speed and efficiency. A concept that was far ahead of its time and that would later be consolidated as the basis of Allied mechanized warfare.

On the 4th of April of 1941, Patton was officially designated commander of the second armored division, which at that time had more than 1,000 tanks of various models, including the M3 Stewart and the M3 Lee, vehicles that, although inferior in armor and firepower compared to the German Panzas, would serve as the core of the American armored force.

It was while in command of this division that on the 7th of December of 1941, he received the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. An event that radically changed the course of the United States and dragged it directly into the Second World War. This event transformed Patton’s preparation and training.

Instruction went from being theoretical and experimental to focusing on the intensive preparation of troops for a global conflict. During 1,942, Patton organized extensive maneuvers in the Imperial Valley of California, where he personally supervised exercises that simulated combat in desert and open terrain, which allowed his troops to become familiar with rapid maneuvers and the coordination of armored units, artillery, and logistical support. His training methods were rigorous and demanding. Patton did not tolerate

mistakes and kept his men at a maximum level of readiness, insisting on speed, precision, and aggressiveness in each maneuver. It was during this stage that he pronounced one of his most famous phrases, “The objective is not to die for your country, but to make the enemy die for his, reflecting his philosophy of offensive warfare and determination.

” On the 8th of November of 1942, Patton led Operation Torch, the first American landing in North Africa. specifically in Morocco then under the authority of Vichi France. His impatience to enter combat led him to make an initial mistake. He ordered the cruiser USS Augusta to open fire on the coast to clear possible defenses which provoked the immediate response of the French batteries and the loss of several barges as well as casualties among the disembarked.

However, this initial confusion did not stop his advance. At dawn, his 33,000 men landed between Media and Fidala, facing fierce resistance from the Vichi French troops. After several hours of fighting, Patton managed to overcome the enemy defenses and advanced 25 km with his armored units, culminating in the entry into Casablanca, which secured the city and strategically Morocco for the Allies.

This success strengthened his reputation as a bold commander capable of combining aggressiveness with tactical improvisation. At the beginning of 1943, the American forces suffered a severe setback in the battle of the Casarene Pass in Tunisia against the experienced Africa Corps of Marshall Irwin Raml. The defeat exposed serious shortcomings in the American command, the lack of coordination and the insufficient preparation of the troops in the face of German mobile warfare tactics.

As a consequence, General Lloyd Fredendall, then responsible for the second army corps, was relieved of his post. On the 7th of March of 1943, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, appointed George Patton to command the Second Corps, entrusting him with the responsibility of reorganizing the forces and returning the offensive to the Allies.

Against all odds and facing a clear tactical inferiority, Patton became the first American general to defeat the Africa Corps during the Battle of Elgatar. His tactics combined the mobility of tanks with surprise attacks and the coordination of artillery, overcoming the apparent superiority of the Italo German forces.

During this campaign, the Axis forces suffered about 6,000 casualties and the loss of 40 tanks, while the Americans, although also paying a high price, 5,000 casualties and 55 armored units destroyed, managed to inflict a decisive strategic blow, demonstrating that the American army could quickly learn from its mistakes and respond effectively to the German threat.

The victory at Elgatar not only consolidated Patton’s reputation as a bold and resolute commander, but also marked a turning point in the North African campaign, raising the morale of the Allied troops and laying the foundations for subsequent offensives that would culminate in the expulsion of the Axis from the African continent.

The merit was greater if one considers that the Americans fought with Sherman and Stewart tanks, light and poorly armored, against the Panza 3, Panza 4, and the feared Tiger, equipped with the 88 mm cannon, one of the deadliest of the era. Patton’s prestige grew immediately. After Elgatar, many considered him the new desert fox after Raml.

He advanced rapidly across the Sahara, even using his personal plane, a Stinson Voyager, to supervise the movements of his troops in the desert. His campaign culminated successfully during Operation Vulcan in 1943 after the capture of the port of Bizerte, an action that put an end to the Tunisian campaign.

During those days, Patton, deeply influenced by his obsession with military history, even went so far as to proclaim himself the spiritual heir of Hannibal Barker when visiting the ruins of Zama, where the Carthaginian was defeated by Scipio Africanis in the year 202 BC. Shortly afterward, on the 10th of July of 1943, Patton was placed in command of the 7th American Army in Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily.

His troops landed along 80 km in the south of the island with the initial objective of taking Gila. For 3 days, he directed intense combat against Italian defenders and repelled a counterattack with Tiger tanks with the support of his friend and tactical ally, General Omar Bradley, head of the second army corps.

In Sicily, Patton encountered a direct rival, the British marshal Bernard Montgomery, commander of the 8th Army. Montgomery was supposed to conquer the port of Msina, but his troops became stalled in Katania before the firm Italian and German resistance. Between the two generals, a fierce rivalry arose. Montgomery, methodical, and cautious, contrasted with Patton, aggressive, impulsive, and bold.

Frictions were inevitable. Convinced that he could advance faster, Patton requested permission from his superior, the British General Harold Alexander, to launch an offensive toward Palmo with the intention of encircling the Italo German forces. At first, Alexander rejected the proposal to avoid clashes between the British and the Americans.

However, Patton, impatient, issued an ultimatum. General, I ask you to remove the handcuffs from me and allow the seventh army to advance north, take Palemo, and split the enemy in two. Finally, Alexander agreed and on the 22nd of July of 1,943, Patton took Palmo, capturing 44,000 Italian prisoners.

From there, he began a rapid race along the northern coast of Sicily toward Msina, determined to arrive before Montgomery. On the 17th of August, his armored units entered the port just a few hours before the British troops. The conquest of Sicily was one of Patton’s greatest triumphs. Not only did he humiliate Montgomery, but he placed the United States in a position of military prestige superior to that of the United Kingdom within the alliance.

However, that success was almost overshadowed by an incident that nearly ruined his career. During the campaign, Patton visited a field hospital near Troer, where he spoke with and encouraged seriously wounded soldiers. On leaving, he came across a young soldier sitting on a box, apparently unheard. Intrigued, he asked him, “What is the matter with you, boy?” “Nothing, General. I just cannot take it.

” The boy was suffering from a nervous breakdown, a frequent condition in modern warfare known as combat fatigue. Patton’s reaction would be remembered as one of the most controversial episodes of his career. The episode at the Troina Hospital became one of the most commented upon of Patton’s career, not only because of the nature of the incident, but also because of the repercussion it had on public opinion and on Allied strategy in the Mediterranean.

The soldiers initial reaction, apparently uninterested or fearful, was interpreted by Patton as an insult to military discipline and to the courage of his men, a principle he considered sacred. His impulsive character and rigid conception of honor led him to act without measuring consequences, and the gesture of slapping the young man, though extreme, reflected his conviction that cowardice could not be tolerated under his command.

The immediate effect was surprising. The soldier, humiliated but recognizing Patton’s authority, stood up and returned to the front, actively participating in later combat. However, the incident quickly transcended the confines of the hospital and reached the press through informal channels before being amplified by Drew Pearson, one of the most influential journalists of the time.

The media coverage included sensationalist comments that portrayed Patton as a violent and uncontrolled officer, generating a national debate about military discipline and the limits of the treatment of wounded or traumatized soldiers. Congress and public opinion reacted energetically. Several newspapers published editorials asking for his dismissal while a senator even requested a court marshal.

Thousands of soldiers relatives believed that their sons were being mistreated which added political and social pressure on the high command. Faced with this situation, Dwight D. Eisenhower, aware of the impact of the scandal, suspended Patton from all his functions for one year, removing him from the planning and execution of crucial operations in Italy. The suspension of Patton had significant strategic implications.

While he remained inactive, the American troops in the Italian peninsula were led by more cautious and less aggressive generals, which delayed the Allied advance and allowed the Axis forces to consolidate defensive positions. Patton, known for his speed and boldness, could have taken tactical opportunities more decisively, avoiding unnecessary prolongations of the campaign.

During this time, while the conflict continued its course, Patton remained in Great Britain, giving lectures, training fictitious units for deception operations, and maintaining his professional prestige among his peers. Although at the public level, his image was temporarily tarnished. The incident, however, did not diminish his reputation within the army.

Rather, it consolidated his figure as an inflexible commander capable of demanding the maximum from his men and of putting military effectiveness in the foreground even in the face of political and media criticism. This mixture of controversy, extreme discipline, and strategic capacity would mark the style that Patton would carry with him during the rest of the Second World War, showing that even public mistakes could be managed to maintain the cohesion and effectiveness of his troops in decisive combat scenarios. During his period of inactivity in Great Britain, between the

end of 1943 and the beginning of 1944, George Patton maintained a constant presence in the public and military sphere. Although away from the front line, he used that time to give lectures on armored tactics and military leadership in addition to granting interviews to various media where he did not hesitate to show his controversial and direct character.

His criticisms of the Soviet Union, at that time, an ally of the United States and of Free France, reflected not only his disdain for what he considered political indecision, but also his strategic vision of a conflict that he believed should be resolved with speed and effectiveness. He often appeared at public events accompanied by his dog Guiller Mito, a small terrier he proudly displayed, consolidating an image that was approachable and at the same time eccentric, arousing both sympathy and curiosity. Eisenhower, aware of Patton’s enormous talent and his capacity to influence both troop

morale and enemy perception, decided to incorporate him strategically into Operation Fortitude. This operation consisted of a complex deception designed to confuse the German high command about the true location of the Allied landing in Western Europe.

Patton was designated commander of the supposed First United States Army, a fictitious unit that existed only on paper, false radios, and inflatable rubber tanks distributed in simulated locations. Patton’s reputation among the Germans was such that the N@zi high command was firmly convinced that he would lead the main invasion through the Pauala.

The operation was so successful that it contributed significantly to the real invasion in Normandy on the 6th of June of 1944, encountering less resistance than expected, thus securing a solid beach head for the allies. Once his mission as a key piece of the deception was accomplished and after almost one year of sanction for the hospital incident in Sicily, Patton was reinstated by Eisenhower and placed in command of the American Third Army in the summer of 1944.

His former campaign companion, Omar Bradley, who now held a higher rank as commander of the second army group, supervised his performance. As soon as he assumed command, Patton deployed his habitual boldness and tactical vision. During the offensive in a ranches, he executed a lightning attack that broke the German lines and allowed large enemy contingents in Britany to be isolated, neutralizing the fortified naval base of breast and destroying the organized resistance of the occupation divisions.

Later in Operation Cobra, Patton carried out an enveloping maneuver that allowed his divisions to turn toward Normandy and close the well-known fal’s pocket. At this point, approximately 60,000 German soldiers were trapped, unable to escape and were forced to surrender.

The operation demonstrated the combination of speed, aggressiveness, and coordination that defined Patton’s style. Tanks advancing in formation, infantry protected, and constant air support sewing chaos in enemy lines. This victory consolidated his reputation as one of the most brilliant commanders of the conflict and at the same time again eclipsed British marshal Bernard Montgomery who had been stalled for weeks in K.

Patton’s ability to quickly regain the momentum of the Allied offensive and to exploit the enemy’s mistakes became a classic example of his operational genius reinforcing his status not only as a military leader but also as an indispensable figure in the strategy of the western campaign. After the dazzling campaign in Normandy, George S. Patton became a symbol of American offensive drive.

His talent for maneuver warfare and his tactical strategic aggressiveness were widely recognized, and he did not hesitate to show his characteristic ironic humor. When praising his men, he pronounced one of his most remembered phrases, “They are sons of bit, commanded by the biggest son of Bit,” referring to himself, which reflected both his confidence in the capacity of his troops and his bold sense of humor, capable of motivating and uniting his soldiers even in the tensest moments. Once the operation was concluded, Patton did not

wait to receive orders or to coordinate bureaucratically with his superiors. Convinced that speed and initiative were decisive, he advanced toward the border of the Third Reich, determined to penetrate deeply into German territory and shorten the war decisively. However, logistics imposed a limit.

Near Verdon, his armored units were paralyzed by lack of fuel. The situation was not casual. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar Bradley had deliberately restricted the gasoline supply, fearful that Patton would launch an offensive that could result in disaster in case of being isolated in enemy territory without air support or reserve reinforcements. Patton’s frustration was immediate.

He considered that his aggressive and rapid style was the best way to defeat the enemy, and he did not hesitate to accuse his superiors of favoring British marshal Bernard Montgomery, whose slower advance contrasted with the American boldness. With his habitual frankness, and without holding back, he exclaimed, “If you had let me continue, I would have finished the war.

In 10 days, I would reach the Rine.” The irony of the situation did not escape his subordinates who understood that Patton was convinced that the opportunity for a decisive blow was within his reach. Faced with the limitation of his resources, Patton directed his offensive toward Lraine, a strategic region on the Franco-German border.

The dense forests and German defenses turned every kilometer advanced into a hard and constant fight. During two months of fierce combat, the Third Army managed to conquer the fortress of Mets on the 23rd of November of 1,99944. [Music] A stronghold considered almost impregnable by the Allies. The capture of Mets not only provided a strategic boost, but also immense moral value.

It showed that even against medieval fortifications modernized with contemporary artillery, aggressiveness combined with rapid maneuvers could overcome enemy defense. With no time to rest, in December, the Germans launched their last great effort on the Western Front, the Battle of the Arden.

The offensive surprised the Allied forces in Belgium and Luxembourg, causing the destruction of several American divisions and leaving the 101st Airborne Division isolated in Bastonia. The situation was critical. The soldiers, exhausted and besieged, faced freezing temperatures, shortage of supplies, and constant attacks from German artillery and armored units. Morale was at the limit and the prospect of a general collapse seemed imminent.

At that moment, Eisenhower turned to Patton, the only general capable of changing the situation through the speed of his decision and the effectiveness of his tactics. When the Supreme Commander asked him how much time he would need to reorganize his forces before going to the aid of Bastonia, Patton answered without hesitation, “Now.

” This response encapsulated not only his audacity but also his vision of war as an art in which immediate initiative could decide the course of events. Patton mobilized his armored divisions with surprising efficiency.

Despite the snowstorm, the shortage of supplies and the mechanical superiority of the German panzas, his third army advanced rapidly through the Belgian forests, overcoming ambushes and isolated resistance. Coordination with the Allied aviation was key. Bombers and fighters cleared routes, destroyed resistance points, and opened the way for the American tanks.

The meticulous planning and simultaneous improvisation, characteristic of Patton, allowed Baston to be saved in record time. The outcome of the operation was as surprising as it was dramatic. The tanks of the Third Army entered Bastau, liberating the 101st Airborne Division and stabilizing the Western Front.

Patton’s action not only saved thousands of surrounded soldiers, but also broke the German offensive, closing the last hopes of the Third Reich to reverse the situation in Western Europe. With his bold intervention, Patton demonstrated that speed, aggressiveness, and initiative could overcome even a strong and prepared enemy, consolidating his reputation as one of the most brilliant and controversial strategists of the Second World War.

His armored columns marched immediately northward in almost impossible conditions. The German tanks were better equipped. The winter struck with blizzards that blinded the terrain. Supplies were scarce and the Luftvafa dominated the sky due to the lack of allied air cover. At the head of the German troops was also one of their most competent commanders, Marshall Gerd Fon Runet.

The situation became critical. His men advanced exhausted without rest or food for days, and the ambushes in the forests caused a high number of casualties. For the first time, Patton was on the verge of a real defeat. In the midst of desperation, he turned to his faith. He ordered his chaplain, James O’Neal, to draft a prayer asking for good weather.

The general was convinced that only with clear skies could the Allied planes intervene. And against all odds, the next day dawned sunny. The advance of Patton over Germany at the beginning of 1945 was a demonstration of his strategic audacity and his talent for maneuver warfare.

After the liberation of Bastonier, his forces did not limit themselves to occupying defensive positions, but continued with a relentless offensive, taking advantage of the mechanical superiority and the high morale of his troops. The Zigfrieded line, considered an almost impregnable obstacle by the Allies, did not stop Patton.

Through coordinated attacks of artillery, infantry, and armored units, he managed to penetrate the German defenses, forcing the enemy units to retreat under constant pressure. The Third Army under his command advanced rapidly through the Palatinate, crossing difficult terrain, wooded hills, and rivers that required ingenuity and impeccable logistics. Patton personally supervised the movement of his divisions using detailed maps and his own tactical sense to coordinate attacks on multiple fronts. The capture of key cities not only had strategic value, but also symbolic.

Trier cobblins and mines were essential communication and transportation centers for the Vermacht and their capture meant the interruption of German supply and retreat lines accelerating the collapse of the western front in the region of Alsace and the SAR Patton faced a more organized and fierce resistance.

The German soldiers aware that they were facing the third army tried to delay the offensive with ambushes, mines, and surprise attacks. But the discipline and quick reaction of the American troops combined with the massive use of armored units and air support made any attempt to stop Patton futile.

Coordination with the Allied aviation became key. Tactical support planes, bombers, and fighters attacked fortified positions and reinforcement columns, allowing the tanks to advance without stopping too long. The morale of Patton’s troops was high.

Known for his charisma and his direct style, he inspired confidence in his officers and soldiers, frequently visiting the front and ensuring that communication was fluid among the different army corps. His ironic humor and closeness to his men, although often controversial, created a fighting spirit that translated into quick and decisive victories.

The occupation of trier with only two divisions, defying Bradley’s warnings, became an example of his philosophy. Initiative and audacity could overcome rigid planning and the numerical superiority of the enemy. Each city taken by Patton weakened the German defensive capacity and accelerated the general collapse of the Reich. Coblins and Bingan located on important river routes ensured allied control over the Moselle river while mines worms and Ludvikharen were vital for industry and transport bridges.

The speed of the offensive also surprised the allies themselves. Omar Bradley and other generals recognized that the Third Army was moving at an unusual pace, establishing a precedent for modern mechanized warfare and consolidating Patton’s reputation as one of the boldest strategists of the Second World War. On the 22nd of March of 1945, George Patton carried out one of the most emblematic actions of his career, the crossing of the Ry River.

His engineers quickly built an improvised bridge, allowing the American Third Army to cross the mighty river before the Germans could react. This maneuver isolated approximately 37,000 German soldiers who were trapped without the possibility of reorganizing their defenses. Patton with his usual sense of humor and strategic ego sent a letter to his friend and commander Omar Bradley which said Brad tell everyone I want the world to know that the third army has crossed the rine before Montgomery. The event was not only a tactical

triumph but also a symbolic blow that reinforced his reputation before the allies and his rivals particularly Montgomery whose caution contrasted with the audacity of the American general. After crossing the Rine, Patton did not stop.

He continued his relentless advance through Germany, deploying rapid maneuvers that dismantled the enemy defenses. During this phase, he managed to capture 82,000 German soldiers at a surprisingly low cost to his own forces. Barely, 143 casualties among his troops. The speed and force of his movements demonstrated the effectiveness of his combination of armored units, infantry, and air support, a strategy he had perfected during years of previous campaigns.

In April of 1945, the Third Army converged on the industrial Ruer Basin, a strategic area vital for German military production. In a lightning operation, Patton’s forces encircled 400,000 German soldiers who surrendered practically without fighting, marking a record for a single Allied general in terms of prisoners captured during the entire war.

The magnitude of this victory not only weakened Germany’s defensive capacity, but also accelerated the total defeat of the Third Reich. Patton’s final offensive consisted of a dizzying advance of approximately 50 km daily toward the Ela River and the Bavarian region, conquering 84,860 km of German territory. His units combining mobility and firepower inflicted enormous casualties on the German army.

20,100 dead, 47,700 wounded, and 653,140 prisoners. While the Third Army suffered only 2,20 dead, 7,954 wounded, and 91 missing figures that reflected Patton’s tactical superiority and his ability to exploit the weaknesses of the enemy. After crossing Bavaria, the Third Army penetrated Czechoslovakia, occupying the western part of Bohemia.

After a brief but intense battle, Patton’s forces captured the city of Pilson on the 6th of May of 1945. However, he was not allowed to advance toward Prague since the diplomatic agreements between Washington and Moscow stipulated that the Red Army would be in charge of occupying the Czech capital. This fact deeply frustrated Patton, who went so far as to accuse communist infiltrators within the American general staff of limiting his operations.

Despite this restriction, the balance of his campaign was impressive. From his first actions in Africa to his last stop in Pilson, Patton had led his troops to conquer a total of 210,000 square miles kilm of enemy territory. His ability to combine speed, aggressiveness, and an effective use of logistics and air support turned the third army into a formidable war machine and pattern into one of the most brilliant and feared generals of the Second World War. This series of victories not only consolidated his military prestige but also left an

indelible mark on the history of war, demonstrating that audacity and initiative could change the course of conflicts in a decisive way. Post war. After the Allied victory in Europe, George Patton found himself in a situation that tested not only his military career but also his personal vision of war and occupation.

For a man accustomed to action and to the command of large combat formations, administrative tasks and the supervision of occupied territories were a constant frustration. In June of 1945, Patton requested to be sent to the Pacific front to continue the fight against the Japanese Empire. Convinced that his leadership could accelerate the end of the conflict in Asia, but his superiors rejected the request.

Instead, he was assigned administrative functions in Germany, initially as provisional commander of Bavaria, a key region due to its strategic importance and its role in the recent history of the N@zi regime. During his stay in Germany, Patton adopted an unconventional and controversial approach regarding the occupation.

He firmly believed that former officials of the National Socialist Party could be useful in the reconstruction of the country, provided they demonstrated competence and knowledge of the territory. This decision provoked strong criticism both within the army and in international public opinion since many saw in it a gesture of indulgence toward those responsible for the N@zi regime.

Patton defended his position with pragmatic arguments. The main objective was to stabilize Germany and ensure that the transition to an allied government was effective, avoiding administrative chaos and disorganization that could favor communist or extremist movements in the country. His blunt character and direct style led him to public confrontations.

Patton openly criticized the Soviet Union, then an ally of the United States, and made controversial comments about certain communities as well as about American occupation policy. He even had a verbal altercation with Soviet Marshall Gorgi Jukov, reflecting his distrust of communist expansion in Europe and his discontent with allied cooperation under the structure of Potdam and other occupation agreements.

These actions combined with his media notoriety and his reputation as irreverent contributed to generating enormous political and military controversy both in the United States and in Europe. The situation culminated on the 7th of October of 1945 when the American authorities decided to remove him from the command of the third army and reassign him to the command of the fifth army whose main function was to supervise denassification and administrative control in Germany.

Patton accepted the position with evident displeasure and humiliation, considering it a lesser post compared to his experience in commanding combat units. This reassignment reflected the tension between his military talent and his controversial behavior.

Although he was a brilliant strategist, his opinions and temperament clashed with official occupation policy and with the need to maintain stable diplomatic relations with the allies. During his time at the head of the fifth army, Patton continued to apply his military judgment and characteristic methods. He precisely evaluated local officials, cared for the morale of his troops, and maintained strict control over administrative processes, attempting to accelerate reconstruction without giving in to inefficiency.

However, his style clashed with American bureaucracy and with Eisenhower’s directives, who prioritized political coordination over individual initiative. Patton, accustomed to direct action and tangible results, saw civil administration and denassification as slow and frustrating tasks which limited his ability to influence the political and military future of Germany.

This post-war period showed another facet of Patton, that of a brilliant general trapped in the politics of occupation, where military success did not guarantee recognition nor freedom of action. His legacy in postwar Germany is complex. On one hand, he stabilized key regions, avoided serious disorder, and contributed to the efficient reconstruction of certain areas.

On the other hand, his decisions and comments provoked diplomatic tensions and fueled controversy about his suitability for high positions in times of peace. Despite these controversies, Patton’s reputation as one of the boldest and most effective commanders of the Second World War remained intact, consolidating his figure as a leader who, even in times of administration and occupation, maintained a pragmatic, direct, and bold approach, always oriented toward action and effective control of territory.

During his post-war period, George Patton maintained his energetic character and his desire to combine military life with his taste for European history and culture. He took advantage of the relative calm of his administrative functions to travel through different cities of the continent.

Exploring not only the most emblematic urban centers, but also places full of historical meaning that had been the scenes of past conflicts. He visited Paris, Ruan, Chartra, Rams, Verda, Mets, Brussels, and Stockholm, showing a particular interest in medieval constructions, the battlefields of the First World War, and the monuments that remembered resistance and military victories. For Patton, each trip was an opportunity to learn tactics of the past and to reflect on war, leadership, and strategy, always with the passion of a scholar obsessed with military history. Despite being in non-combat functions, his personality

did not diminish. He continued to be blunt and controversial, openly criticizing the internal policies of the United States, the decisions of his superiors, and the way in which the occupation of Germany was being carried out.

He did not hesitate to express his frustration over bureaucracy, the slowness in the rehabilitation of territories and the Soviet influence in European politics, generating constant tensions with high-ranking army officers and allied officials. His impatience and his lack of political diplomacy contrasted with his ability to lead troops and make quick decisions on the battlefield, reminding everyone that even if he was a figure of the postwar, his mind was still focused on action and military effectiveness.

On the 9th of December of 1945, while traveling in a jeep accompanied by another general, Patton’s life took a tragic and unexpected turn. During the journey, the vehicle collided with a truck driven by Sergeant Robert Thompson. The crash was violent and caused serious fractures in Patton’s neck as well as irreparable damage to his spinal column.

He was immediately taken to the hospital in H Highleberg where he remained hospitalized for weeks. His treatment included multiple medical interventions and intensive care, but nothing managed to reverse the severity of his injuries. Patton, accustomed to physical resistance and overcoming adversity, found himself completely incapacitated, experiencing constant pain and total limitations in the movement of his body.

After the accident, he was rushed to the military hospital in H Highleberg where doctors carried out various interventions and treatments, all unsuccessful. Patton suffered for almost two weeks from intense pain while his family traveled from the United States to accompany him in his final days.

His condition became complicated due to a pulmonary edema that seriously affected his breathing and that combined with the fractures and paralysis weakened his body until causing a heart attack. During his hospitalization, he received the visit of his family who traveled from the United States to accompany him in his last days.

Despite the presence of loved ones and a dedicated medical team, his health progressively deteriorated. A pulmonary edema further complicated his situation, affecting his respiratory capacity and weakening his heart. Finally, at 6:00 in the morning of the 21st of December of 1945, George Patton died of a heart attack, putting an end to the life of one of the boldest and most renowned generals of the Second World War.

On his deathbed, Patton expressed his last wish to be buried next to the men he had commanded on the battlefields, once again demonstrating his devotion to his troops and his deeply military character. Fulfilling his will, his remains were transferred to the cemetery of Ham in Luxembourg, a place full of meaning since there he had led the famous counteroffensive in the battle of the Arden.

Patton’s death not only marked the end of an extraordinary military career but also closed the chapter of a complex figure. A charismatic, controversial, bold, controversial leader deeply convinced of his historic mission. His legacy transcended American and European borders, consolidating him as one of the most brilliant generals of the Second World War.

Remembered both for his bold maneuvers and triumphs in combat and for his energetic, controversial, and singular personality. George Smith Patton Jr. left a legacy that goes far beyond the titles and decorations he accumulated throughout his career. His life was a testimony of the power of charismatic leadership, audacity in combat, and the ability to decisively influence the course of history.

from his first baptism of fire in the punitive expedition against Panchcho Villa where he demonstrated his personal bravery by shooting down Vilista leaders and taking calculated risks with barely a small contingent to his legendary campaigns in North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, and the heart of Germany. Patton became a model of a general capable of combining speed, tactical ingenuity, and strategic aggressiveness.

His personality, marked by an impetuous temperament and a constant desire for action, generated both admiration and controversy. He did not fear challenging his superiors, arguing with British allies such as Montgomery, or making controversial statements about international politics and communist movements in Europe, even when this meant putting his own career at risk.

This mixture of boldness, controversy, and theatricality turned him into a media figure before the word celebrity was applied to military figures. His famous relationship with his dog, Guermito, his extravagant style of wearing impeccable uniforms, and his habit of carving notches on the grip of his pistol as a memory of each victory contributed to the construction of a personal myth that transcended the strictly military sphere.

On the battlefield, Patton demonstrated a deep understanding of mechanized warfare and mobility. His successes during the Second World War were not only the product of bravery, but also of a meticulous analysis of logistics, terrain, and enemy behavior. Operation Cobra, the liberation of the Ruer Basin, and the swift offensive toward Bavaria and Czechoslovakia illustrate his ability to combine strategic intelligence with rapid execution, minimizing his own casualties while maximizing the impact on much larger enemy forces. His style of leadership emphasized the individual initiative of

his subordinates, strict discipline, and the constant motivation of his troops, with the conviction that an inspired and energetic army could overcome any obstacle. Patton was also a student of military history and his fascination with figures such as Julius Caesar, Scipio Africanis, Hannibal and Joan of Ark notably influenced his vision of war and leadership.

He firmly believed that the understanding of past tactics and strategies was essential for success in the present and many of his decisions reflected a bold interpretation of those historical lessons. This link between past and present allowed him to innovate with armored warfare, consolidating doctrines that would be fundamental in later conflicts.

The end of his life, tragic and premature after the automobile accident in December of 1945, did not overshadow his greatness nor his influence. To be buried in the cemetery of Ham alongside the men he had commanded and liberated barely one year before symbolized his total identification with his troops and his conviction that a leader should share both the victories and the sacrifices of those who followed his orders.

To this day, Patton is remembered not only as a brilliant strategist and a bold soldier, but also as a cultural icon who embodied the image of the intrepid, determined, and theatrical American general whose life and career continue to inspire historical studies, films, books, and documentaries. His legacy uniquely combines tactical rigor, relentless discipline, personal charisma, and a vision of leadership that integrated history, military psychology, and the ethics of rapid and decisive action. He was a man who not

only won battles, but also built a myth. A general who understood that war is not fought only on the field, but also in perception, in the morale of his troops, and in the way his boldness could change history in an instant. The figure of Patton continues to be a reference for the study of military leadership, mechanized war strategy, and the relationship between personality and success in war history, consolidating him as one of the most brilliant and controversial minds of the American army and of world military history. George Patton was much more than an American

general. He was a bold strategist, a daring leader, and a man whose explosive personality became legend. From his first combats in the punitive expedition against Panchcho Villa through his pioneering work in armored warfare during the first world war to his brilliant campaigns in Africa, Sicily, Normandy, and the heart of Germany, Patton left an indelible mark on military history.

His tactical genius combined with strict discipline, undeniable charisma, and a touch of constant controversy. Characteristics that redefined leadership in combat, and turned him into a reference for generations of soldiers. Throughout his career, he not only liberated cities and defeated enemy armies, but also inspired respect and admiration for his boldness and determination, imposing his rhythm relentlessly on the battlefield.

Although his life ended prematurely after a tragic automobile accident in Germany, his legacy endures. Patton symbolizes the strength, calculated aggressiveness, and strategic vision that transformed the American army into a decisive force during the Second World War. With his victories, his controversies, and his charisma, George Patton remains in historical memory as one of the greatest generals of all time. A man who embodied the fighting spirit and the passion for war until the last day of his

News

CH2 How One Girl’s “STUPID” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

How One Girl’s “STUPID” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster At 6:43 a.m. on March 1,…

CH2 Japanese Couldn’t Believe One “Tiny” Destroyer Annihilated 6 Submarines in 12 Days — Shocked The Whole Navy

Japanese Couldn’t Believe One “Tiny” Destroyer Annihilated 6 Submarines in 12 Days — Shocked The Whole Navy The Pacific…

CH2 German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted Defeat Against The Army That Never Starved

German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted Defeat Against The Army That Never Starved December 17, 1944. The…

CH2 December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – Patton Turned 250,000 Men In 48 Hours

December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – Patton Turned 250,000 Men In 48 Hours December 19,…

CH2 What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time

What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time December 7, 1941. It…

CH2 Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult

Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult On the morning of August 3rd, 1943, the…

End of content

No more pages to load