How Did Hitler Fund a Huge Military When Germany Was Broke?

Germany, 1923. The winter air was sharp and cold, but colder still was the silence that settled over a nation watching its own money turn to ash. People stood in lines outside bakeries that had no bread to sell. Men pushed wheelbarrows piled high with banknotes that wouldn’t buy a single loaf. Children played with stacks of worthless bills as if they were blocks, building castles from currency that had lost all meaning. Housewives burned bundles of marks in their stoves because the paper burned hotter and longer than the firewood they couldn’t afford.

A single U.S. dollar was worth four trillion marks. Prices doubled between sunrise and sunset. Restaurants changed their menus mid-meal, waiters climbing on tables to call out new prices before customers had even finished eating. Shopkeepers measured money by weight, not value. A man could leave home a millionaire in the morning and be destitute by the time he returned. Germany was living through the collapse of an economy, but more than that—it was living through the collapse of faith.

The middle class, the bedrock of the Weimar Republic, was destroyed overnight. Lifelong savings disappeared, pensions became meaningless, life insurance policies were jokes. The humiliation went beyond poverty—it was spiritual. The proud citizens of what had once been Europe’s industrial heart now bartered for potatoes and coal, watching their children go hungry while the world moved on without them.

By 1924, the crisis eased. The rentenmark, a new currency backed by land and industrial output, stabilized the system. Germans could buy bread again. Prices stopped spinning. People began to breathe. For a moment, it seemed the nightmare had passed.

Then came 1929.

The Great Depression swept across the Atlantic like a storm. American banks, which had kept the fragile German recovery afloat with loans and investments, called in their debts. The credit lines that had sustained the factories of the Ruhr and the steel mills of the Saar vanished overnight. Thousands of businesses shuttered. Millions of workers were sent home. Within three years, six million Germans were unemployed—almost a third of the entire labor force. Families lined up for soup they could no longer afford. Professors sold pencils on street corners. Former engineers and teachers begged for work as day laborers.

The Weimar government was paralyzed, torn between austerity and chaos. Political violence became routine. Communists clashed with Nazi paramilitaries in the streets of Berlin and Munich. Riots, beatings, arson—Germany’s cities felt less like European capitals and more like frontlines in a war that hadn’t yet been declared. The sense of despair was total. A generation had lost everything twice in less than fifteen years.

It was into this broken, frightened country that Adolf Hitler stepped on January 30, 1933.

He inherited a nation stripped of dignity, shackled by the Treaty of Versailles, and suffocating under economic ruin. The Reich was a shadow of its former self—limited to an army of 100,000 men, forbidden tanks, forbidden aircraft, forbidden submarines, forbidden heavy artillery. And perhaps worst of all, it had no money to change any of it.

But within six years—by 1939—that same nation would launch a war that stunned the world.

Three million soldiers, three thousand tanks, four thousand aircraft. A military more advanced than any in Europe, forged by a government that had been bankrupt less than a decade earlier. The transformation was so total, so rapid, that foreign observers could hardly comprehend it. How had a destitute nation rebuilt itself into a war machine in less than the time it takes to build a single battleship?

The answer began with one man: Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht.

Born in 1877, Schacht was not a soldier or an ideologue. He was a banker—brilliant, calculating, and famously cold. During the crisis of 1923, he had saved Germany once already by stabilizing the mark and creating a new currency backed by land and industrial assets. It worked. The chaos ended. The man who had achieved the impossible became a legend in financial circles, both feared and revered.

Hitler, always quick to recognize genius when it served his purposes, brought Schacht back into the fold in 1933, appointing him president of the Reichsbank. The following year, he became Minister of Economics. His mission was simple and impossible at the same time: rebuild the German economy and rearm the nation without triggering another hyperinflation and without letting the rest of the world see what was happening.

Germany’s enemies were watching. The Treaty of Versailles had banned rearmament outright. The French, the British, and the Americans still had eyes inside German industry. Any obvious buildup would bring intervention, sanctions, maybe even invasion. Schacht needed a way to funnel billions into weapons and factories without leaving a trace on the Reich’s official accounts. He needed invisible money.

In 1934, he found a way.

He created a company—a fake one.

Its name was Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft, m.b.H. It sounded technical and harmless: the Metallurgical Research Corporation. The Germans simply called it by its initials, Mefo. On paper, Mefo was a consortium owned by four major industrial giants—Siemens, Krupp, Rheinmetall, and Gutehoffnungshütte. Its supposed purpose was to conduct industrial research. It had offices, stationery, and a bank account. What it didn’t have was employees, production, or any actual business activity. It was a shell, a financial ghost conjured out of signatures and seals.

Schacht used this phantom to build a parallel economy.

Here’s how it worked. Imagine you’re an arms manufacturer in 1935. The Reich’s Ministry of Defense places an order with you—say, for one thousand Panzer tanks. You complete the order, but when it comes time to get paid, you don’t receive marks from the Reichsbank. Instead, you receive Mefo bills—essentially promissory notes issued by this mysterious research company.

Each bill stated that Mefo promised to pay the bearer a specific amount of money, with interest, in five years. You, as a manufacturer, could take these Mefo bills to a private bank. The bankers knew the truth—that Mefo was a front backed by the Reich. So they accepted the bills as if they were real currency, exchanging them for Reichsmarks at a small discount. You got paid. You could pay your workers, buy steel, and keep your factories running.

Meanwhile, those private banks would in turn take the Mefo bills to the Reichsbank and exchange them for cash. The Reichsbank printed the money quietly and released it into circulation. But because the Mefo bills were officially obligations of a private company, not the German government, none of it appeared in state financial records.

On paper, Germany’s budget looked stable. No inflation, no deficit. To the outside world, the Reich seemed fiscally responsible, even disciplined. In reality, it was running one of the largest and most sophisticated shadow banking systems in history.

Between 1934 and 1938, Schacht’s invisible currency poured twelve billion Reichsmarks into the economy—more than Germany’s entire national debt just two years earlier. It paid for new factories, synthetic fuel plants, and armaments research. It funded the creation of the Luftwaffe, the training of tank crews, and the expansion of the navy. Every new bomber, every new Panzer division, every ton of steel that rolled out of the Ruhr Valley was financed with paper that technically didn’t exist.

Schacht’s brilliance was in the illusion. The Mefo bills were essentially a national-scale Ponzi scheme—debt disguised as private credit, endlessly rolled over to keep the system running. It only worked because everyone involved pretended to believe in it. Industrialists accepted the bills because they trusted that the Reich would pay them. Banks accepted them because they trusted Schacht’s word. The Reichsbank printed quietly because it trusted that war—or something like it—would arrive before the reckoning did.

For a while, it worked flawlessly. The economy boomed. Unemployment plummeted. Construction surged. Propaganda films showed German workers smiling again, rebuilding the fatherland under banners of red, black, and white. Foreign journalists marveled at the “German miracle.” They didn’t see the mountain of invisible debt propping it all up.

By 1938, that mountain was beginning to wobble. The Mefo bills were coming due, and the Reich didn’t have the money to redeem them. The bills could be extended—pushed forward, refinanced—but not forever. The system was eating itself. To stay alive, it needed growth. Expansion. New territory, new plunder, new industries to seize.

That was the unspoken truth of Schacht’s creation: it made war not just desirable, but inevitable. The German economy had been rebuilt on borrowed time. When the debt came due, the only way to pay it was to conquer someone else.

And in early 1939, as Hitler stood in the Reich Chancellery reviewing the latest reports from Schacht’s ministry, every economist in Berlin understood the same thing. Germany could not sustain peace much longer. The illusion was cracking. The question wasn’t if the bubble would burst—it was where Hitler would turn to keep it alive.

The man who had once saved Germany from economic ruin had built a machine that could no longer stop moving.

And when it moved again, the world would follow.

Continue below

Germany 1923. Hyperinflation has destroyed the currency. A loaf of bread costs 200 billion marks. Families burn money in their stoves because it’s cheaper than firewood. Then 1929, the Great Depression hits. Banks collapse. Factories close. By 1933, 6 million Germans are unemployed. 30% of the workforce.

Families are starving in the streets. This is the Germany Adolf Hitler inherits when he takes power in January 1933. A nation economically destroyed twice. But just 6 years later, 1939, everything has changed. Germany invades Poland with 3 million soldiers, 3,000 tanks, 4,000 aircraft, the most modern military in Europe.

In 6 years, this bankrupt nation built the most powerful war machine in the world. How? The answer involves a fake company, a financial wizard, and a national scale Ponzi scheme. The MEO Bills, a shadow banking system that funded Nazi rearmament while hiding it from the world. By 1939, the bills were coming due, and Germany didn’t have the money to pay them.

So Germany had no choice but to invade its neighbors to avoid economic collapse. The Nazi economy wasn’t just built on ideology. It was built on a financial scam that required constant expansion to survive. This is how Hitler paid for World War II and why economic collapse made war inevitable. Before we dive in, imagine this.

It’s January 1939. You’re Germany’s top economist. You know the economy is about to collapse. You know Hitler’s only solution is war. Do you speak up and risk your life or stay silent and let it happen? Real people faced this exact choice. By the end of this video, you’ll understand why every option was bad.

If you’re into history that makes you think, hit subscribe. Let’s start with the crisis that made this all possible. To understand how desperate Germany was, you need to see both catastrophes. First, the hyperinflation of 1923. November 1923, the peak of VHimar hyperinflation. A single US dollar is worth 4 trillion marks.

Workers demanded to be paid twice a day at lunch and at the end of their shift because by evening their morning wages were worthless. Restaurants changed their prices while customers were still eating. Waiters had to climb on tables every half hour to call out new menu prices. Life insurance policies that families had paid into for decades matured into sums that couldn’t buy a single postage stamp.

This wasn’t an economic crisis. This was economic apocalypse. The German middle class. savings, pensions, investments wiped out overnight. Germany slowly recovered. The currency stabilized. Life began to normalize. Then 1929, the Great Depression. American banks call in their loans. German businesses collapse. Unemployment explodes.

By 1932, 6 million Germans are unemployed. 30% of the workforce. Families are auctioning their furniture on the street to buy food. Engineers and teachers are begging for work as laborers. The VHimar government is paralyzed. Political violence is constant. Communist and Nazi street battles are turning cities into war zones.

Germany had been economically destroyed twice in 14 years. This is the environment that brings Hitler to power. In January 1933, Hitler promises to restore German greatness, to rebuild the military, to defy Versailles. But Germany is bankrupt. The Versailles Treaty limits Germany to 100,000 soldiers, no tanks, no aircraft, no submarines, no heavy artillery, and Germany has no money to build them anyway.

Hitler needs to rearm massively, secretly, without anyone noticing until it’s too late. and he needs to do it with an economy that’s been destroyed twice. Enter Yalmar Shakt, the man who would make it possible. Yalmar Horus Greley Shack, born 1877, banker, economist, financial genius. He’d already saved Germany once. In 1923, as currency commissioner, Shacked ended the hyperinflation by creating a new currency backed by land. It worked.

The rent mark stabilized. Shakt became a legend. March 17th, 1933, Hitler appoints him president of the Reichkes Bank, Germany’s central bank. August 1934, Shakt becomes minister of economics. Shak’s job, fund massive rearmament without anyone noticing, without triggering inflation, without revealing the scale of what Germany is doing.

Shak is brilliant and he has a plan. Here’s Hitler’s challenge. Germany needs to build tanks, planes, ships, weapons. That means paying steel companies, arms manufacturers, chemical plants. But if the Reichkes Bank just prints money to pay them, two things happen. First, inflation explodes again. Germans won’t tolerate that. They lived through 1923.

Second, the payments show up on official Reichkes Bank statements. Foreign governments will see them. They’ll know Germany is rearming. They’ll intervene before Germany is ready. Hitler needs invisible money. Money that doesn’t trigger inflation. Money that doesn’t appear on official records. Shakt creates it.

In 1934, Shakt creates a company. Metalluga gazels. MBH, Metallological Research Company, Limited Liability, MEO for short. On paper, it’s a research consortium. Four major German companies Zemens Kup Rinmetal and Gutah Hofnong Hutter own shares in MEO which has a nominal capitalization of only 1 million Reichkes marks total. In reality, MEO does nothing.

It’s a shell, a fake company with letterhead and a bank account. But MEO is about to fund the largest rearmament program in history. Here’s how the scheme worked. Imagine you’re a German arms manufacturer in 1935. The government orders a thousand tanks from you, but instead of paying you in Reich’s marks, they pay you in MEO bills.

These bills are IUS, promisory notes issued by MEO, the fake company. They’re basically checks that say MEO promises to pay you this amount in 5 years. Now, you don’t want to wait 5 years. You need cash now to pay your workers and buy steel. So you take these MEO bills to a private German bank. The bank looks at the bills.

They know MEIO is backed by the Reichs Bank. They know the Reichs Bank will honor these bills. So the bank gives you cash. Real Reichs marks. Maybe at a small discount, but cash. You’re happy you got paid. Here’s where the magic happens. The private bank now holds MEO bills. They take them to the Reichkes Bank. The Reichkes Bank converts them to cash using its money issuing powers.

But here’s the critical part. These transactions never show up on the official Reichkes Bank balance sheet. MEO bills are private obligations. They’re not government debt. They’re not Reichkes Bank debt. Officially, they’re debts of a private research company. So when foreign governments look at Germany’s finances, they don’t see this massive rearmament spending. It’s invisible.

Between 1934 and 1938, Germany issued 12 billion Reichs marks in MEO bills. For context, Germany’s entire national debt in 1932 was about 10 billion Reichs marks. Germany secretly added more than its total debt in hidden obligations to fund rearmament, and nobody outside Germany knew the full scale until it was too late.

By 1936, Germany had violated every military restriction of the Versailles Treaty. They had tanks, aircraft, submarines, a modern army. The Allies didn’t intervene because they didn’t realize how far it had gone. But there’s a catch. Those MEO bills, they come due in 5 years. The first bills were issued in 1934.

They mature in 1939. and Germany doesn’t have 12 billion Reichs marks to pay them back. The clock is ticking and that’s when the Ponzi scheme comparison becomes accurate. A Ponzi scheme works like this. You promise investors high returns. You pay early investors with money from new investors.

It works as long as new money keeps coming in, but eventually you run out of new investors. The scheme collapses. Everyone loses. Nazi Germany’s economy worked the same way. MEO bills were promises to pay later. Germany planned to use future economic growth to pay them off. But by 1938, Germany’s economy couldn’t generate enough revenue to pay the bills.

The scheme needed new money. Where do you get 12 billion Reichs marks when your economy can’t produce it? You take it from someone else. March 1938, Germany annexes Austria, the Anelless. Austria has gold reserves, foreign currency, industrial assets. Germany seizes all of it. September 1938, the Munich Agreement.

Germany takes the Sudatan land from Czechoslovakia. March 1939, Germany occupies the rest of Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia has gold reserves. The Skoda Arms Works, one of the most advanced weapons factories in Europe. Germany seizes all of it. September 1939, Germany invades Poland. Poland has agricultural production, natural resources, millions of people who can be forced into labor.

Germany seizes all of it. The Nazi economy wasn’t just immoral. It was structurally designed to require conquest. As one historian put it, they had to invade a couple of countries for it, though. Yalmar Shak saw this coming. By 1937, he’s warning Hitler that the economy is overheating, that the spending is unsustainable, that they’re heading for collapse.

Hitler ignores him. On January 7th, 1939, just weeks before the first MEO bills come due, Shack submits a desperate report from the Reichkes Bank directors. The report urges drastic curtailment of rearmament spending, reduction of expenditures, a balanced budget as the only method of preventing inflation. Hitler’s response January 20th, 1939.

Hitler fires Shack as Reich’s bank president. Shacked had built the machine, but he’d also built in a time bomb. And Hitler’s solution was to keep the bomb from exploding by constantly feeding it. feed it with Austria, with Czechoslovakia, with Poland, eventually with France, the Soviet Union, everywhere. The war wasn’t just Hitler’s ideology, it was economic necessity.

By 1939, Germany had two choices: economic collapse or expansion. Hitler chose expansion. But MEO bills weren’t the only revenue stream. The Nazi economy had other sources. And they were even darker. When Germany conquered a country, they didn’t just take military control. They systematically looted it. Gold reserves, foreign currency, art, industrial equipment, raw materials.

In France, Germany imposed occupation costs. France had to pay Germany 400 million Franks per day to occupy France. That’s France paying for its own occupation. In the Soviet Union, Germany planned to extract grain, oil, minerals to feed the German war machine. The entire economic model was parasitic. Then there’s slave labor.

Concentration camp prisoners were used as forced labor in German factories, building weapons, manufacturing parts, mining coal. Companies like IG Farbin, Seamans, Croo used slave labor from camps. Prisoners were worked to death. When they died, they were replaced. The Nazi economy wasn’t just funded by theft. It was built on slavery.

This isn’t just immoral. This is the economic structure of genocide. Here’s another scam that shows how deep the theft went. The Volkswagen, the people’s car. Germans were told they could own a car if they saved up through the Deutsche Arbites front. Pay a little each month. eventually get your Volkswagen. 275 million Reich marks were collected from German savers.

How many civilian Volkswagens were delivered during the entire Third Reich? Zero. The factory was converted to military production, the Kubalvagen, a military vehicle instead of the promised people’s car. German savers lost everything. They didn’t get compensation until the 1960s. The Nazi economy didn’t just steal from conquered enemies.

It stole from its own people. Here’s another scheme. In the 1920s and early 1930s, Germany borrowed huge sums from Britain, France, and the United States. The loans were supposedly to help Germany pay Versailles reparations. Germany took the money. Then Hitler stopped paying reparations in 1933, but he kept the loan money. So Germany used money borrowed from Britain and France to build the army that would invade Britain and France.

When Germany invaded France in 1940, the new Vichi government forgave part of the debt. Germany got free money from its future enemies and of course the confiscation of Jewish property. Jewish businesses, bank accounts, homes, art, everything seized by the state, sold, used to fund the regime. This wasn’t just persecution.

It was systematic theft used to finance the government. Every aspect of Nazi economics was built on taking from others. So by 1939, the Nazi economy was running on meo bills, plunder, slave labor, and theft. And none of it was sustainable. By 1939, the Nazi economy was on the edge of collapse. MEO bills were coming due. Germany couldn’t pay them without plundering more countries.

The economy was overheated. Inflation was creeping back. Shortages were appearing. Shacked had warned this would happen. He was proven right. But instead of pulling back, Germany accelerated because pulling back meant economic collapse, unemployment, political crisis, the end of the Nazi regime. Hitler’s only option was forward.

This is the part most people don’t understand about Nazi Germany. The war wasn’t just ideology. It was economic necessity. The Nazi economy was designed to require expansion. Without conquest, it collapsed. Historian Adam Tus wrote a book about this. The wages of destruction, the making and breaking of the Nazi economy. his thesis.

Nazi Germany was living on borrowed time from day one. The economic model required constant warfare to survive. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, it wasn’t just about Laban’s realm or racial ideology. It was about oil from the Caucuses, grain from Ukraine, resources to keep the economy from imploding. The war was the economy.

The economy was the war. And when Germany started losing territory in 1943 and 44, the economic model unraveled. No more plunder, no more resources, just endless expenditure. The Nazi economy was a pyramid scheme. And like all pyramid schemes, it eventually collapsed. So let me bring this all together. How did Hitler pay for World War II? He didn’t.

Let me explain. The Nazi economy was built on four pillars. First, creative accounting. Meo bills allowed Germany to hide 12 billion Reich marks in debt off the books to rearm in secret to build a war machine while the world thought Germany was still recovering. Yalmar Shack’s genius was creating invisible money, but that money was still debt.

And debt comes due. Second, plunder. Germany funded the war by stealing from everyone they conquered. Austria’s gold, Czechoslovakia’s weapons factories, France’s occupation payments, Soviet grain, Polish labor. The Nazi economy was parasitic. It required constant new hosts to survive. Third, slavery. Concentration camp prisoners, prisoners of war, forced laborers from occupied countries, worked to death in German factories, building the weapons used to conquer more countries to create more slaves.

The economic model was inseparable from genocide. Fourth, theft, Jewish property, Versailles loan defaults, canceled reparations, even stealing from German savers through the Volkswagen scam. Every aspect of Nazi economics involved taking from others without compensation. So, was Nazi Germany a Ponzi scheme? Essentially, yes.

Early investors got paid with money from later investors, but the later investors were countries and payment was conquest. Meo bills came due in 1939. Germany didn’t have the money, so they invaded Poland. The loot from Poland funded operations in France. The loot from France funded the invasion of the Soviet Union.

As long as Germany kept winning, kept taking, the scheme worked. But the moment Germany stopped expanding, the whole structure collapsed. This is why the war was inevitable. By 1939, Hitler had two options. Expand or collapse. The Nazi economy wasn’t built for peace. It was built for war. And that’s how Hitler paid for World War II.

With promises he couldn’t keep, with money he didn’t have, with resources he stole. With labor he enslaved, the Nazi war machine wasn’t funded by economic strength. It was funded by a scam that required constant conquest to avoid collapse. And when the conquest stopped, the economy died with the regime. Here’s my question for you.

Knowing that the Nazi economy required constant expansion to survive, do you think the war was inevitable? Or could Germany have pulled back and transitioned to a sustainable economy?

News

CH2 They Mocked His ‘Enemy’ Rifle — Until He Killed 33 Nazi Snipers in 7 Days

They Mocked His ‘Enemy’ Rifle — Until He Killed 33 N@zi Snipers in 7 Days At 6:42 a.m. on…

CH2 Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear On the gray,…

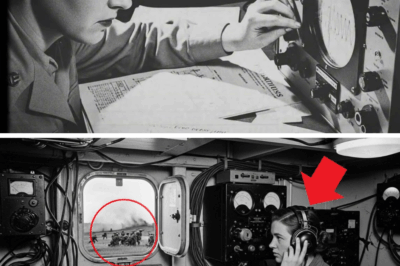

CH2 How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress

How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress At 6:42 a.m. on June 26,…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity… The air in the lower levels of the…

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him The pressure on my…

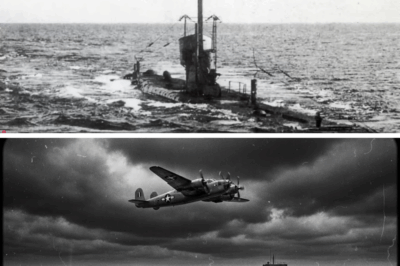

CH2 German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away

German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away June 23rd, 1944. The North…

End of content

No more pages to load