How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon

December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck of the USS West Virginia smelled faintly of soap and laundry starch, the early morning light seeping through portholes onto stacks of neatly folded linens. Dory Miller moved among them, methodical and quiet, gathering sheets and towels, a routine he had performed thousands of times over two years of service. This morning, like every other, the work was mundane, almost invisible—laundry was not glamorous, not heroic, and certainly not life-threatening. Miller was not a gunner, not a sailor in the traditional sense, certainly not a warrior by the Navy’s official reckoning. His rating classified him as a mess attendant third class. His job was to serve, clean, and stay out of the way. At twenty-two, he had internalized what the Navy had made clear: the ship’s firepower, its strategy, its very survival, was not meant for men like him. He was tall, broad-shouldered, six-foot-three, over two hundred pounds, a natural athlete, and yet in the Navy’s rigid hierarchy, all that mattered was the color of his skin.

Born Doris Miller on October 12th, 1919, in Waco, Texas, he had been the third of four sons in a family of sharecroppers. From a young age, he had worked the fields alongside his brothers, sunburnt and calloused before he had even reached his teenage years. His mother had named him after an uncle, and the name had stuck, though it had also drawn ridicule from schoolmates. By the time he was ten, Dory had learned that life required both strength and endurance, that survival was often about persistence and observation. When he turned twenty, like many young black men in the segregated South, he saw the military not as a calling but as an opportunity—a chance to earn a steady wage, to escape the relentless cycle of poverty, to carve a life for himself outside the cotton fields. On September 16th, 1939, he enlisted in the United States Navy at Dallas, Texas.

Basic training at Norfolk, Virginia, was an eye-opening revelation of both discipline and limitation. The Navy would feed him, train him in routines, and instill the skills required for naval life, but it would not prepare him for battle. The segregation policies were strict, codified, and unyielding. Black sailors were restricted to the steward’s branch, tasked with menial labor: cooking, cleaning, serving officers, maintaining quarters. Combat roles, the very essence of naval glory, were denied. Dory learned quickly that no matter his size, strength, or intelligence, his service would be invisible. His talent, ambition, and potential were contained by policy, by prejudice, by a system designed to ensure he would never be entrusted with the ship’s guns.

By the time he reported aboard the USS West Virginia on January 2nd, 1940, he had absorbed this reality. The battleship was one of the most formidable vessels in the Pacific Fleet, a Colorado-class behemoth bristling with artillery and capable of delivering devastating firepower. Dory’s duties were enumerated: serve meals to officers, polish brass, maintain officer quarters, handle laundry, and remain unseen when the ship’s real sailors were at work. He was not trained in damage control, firefighting, or gun operation. The 50-caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine guns mounted across the decks were sophisticated weapons requiring training, precision, and practice. Manuals ran hundreds of pages, detailing loading procedures, aiming techniques, barrel cooling, clearing jams. Dory had never touched these manuals. He had never been assigned to a gun crew. Yet he had watched. He had observed. Every drill, every exercise, every maneuver the gunners executed was a lesson he absorbed silently, studying patterns, memorizing movements, noting the rhythm of loading and firing, how crews coordinated, how the weapons behaved under sustained fire. His mind was attentive, calculating, patient—an observer learning skills he was not allowed to practice.

December 7th, 1941. The morning was calm, deceptively peaceful. At 7:55 a.m., the first wave of Japanese aircraft appeared over Pearl Harbor. Dory Miller was below deck, still attending to his laundry duties, unaware of the magnitude of what was about to unfold. The ship was at modified condition three—a minimal readiness appropriate for a Sunday morning. The events of the previous days had seemed routine, almost mundane. Reports of a submarine sighting by the USS Ward earlier that morning had been logged and largely ignored. Radar stations at Opana Point had detected approaching aircraft, but the warnings were dismissed as false alarms, a routine precaution.

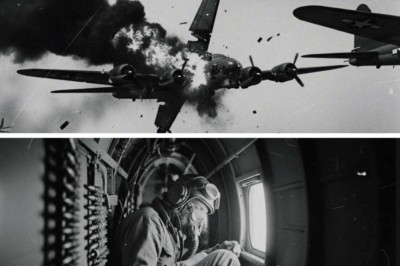

Then, at 7:55 a.m., everything changed. Lieutenant Commander Mitsuo Fuchida gave the signal, Tora, Tora, Tora, Tiger, Tiger, Tiger, confirming the element of surprise had been achieved. The first torpedo struck the West Virginia at 7:56 a.m., followed quickly by others. Over the next eight minutes, seven torpedoes would hit the ship, each carrying over four hundred pounds of explosives. The blasts tore through the hull below the waterline, opening massive gashes that flooded compartments instantly. The ship shuddered violently beneath the sailors’ feet. Lights flickered, alarms blared, and chaos erupted as the general quarters were sounded. Crew members shouted orders, scrambled to stations, and struggled against rising water and smoke. Men were trapped below, fighting against the sudden, violent intrusion of oil-contaminated water through the deck plates. The organized drill of a battleship crew became a desperate scramble for survival as fire, water, and steel collided.

Dory Miller’s world shifted in an instant. His assigned station, the anti-aircraft battery amidships, was unreachable. The passageways were blocked by flooding, debris, and the panicked movement of sailors trying to reach their posts. Trained gunners scrambled to mount their weapons, but the chaos left many vulnerable. Miller, trained in none of this, faced a decision that no one had prepared him to make. The laundry he had been handling moments before seemed absurdly trivial compared to the life-or-death moment now pressing down upon him. With fire and torpedo blasts all around, with officers calling out orders and men struggling against both water and fear, he realized that remaining in his designated role would achieve nothing. Trained or not, his path was blocked, and the ship itself depended on action, not adherence to the Navy’s imposed limitations.

In that moment, Dory Miller made a decision.

Continue below

December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck of the USS West Virginia. Dory Miller is doing what the United States Navy trained him to do. He’s collecting laundry, not manning guns, not preparing for battle, not even cooking, though that’s what his rating says, laundry. This is the job the Navy has decided a black man from Waco, Texas, is qualified to perform on a battleship.

Miller is 22 years old. He’s been in the Navy for 2 years. In that time, he’s learned to make beds, serve officers, and wash dishes. The Navy regulations are clear. Black sailors are restricted to the steward’s branch. No matter how strong, how smart, or how capable, the color of your skin determines your ceiling. Dory Miller is 6’3 in tall.

He weighs over 200 lb. He’s the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion. But on this Sunday morning, his most important duty is making sure the white officers have clean sheets. He was born Doris Miller on October 12th, 1919 in Waco, Texas, the third of four sons to Henrietta and Connory Miller. His mother named him Doris after her brother.

The name would follow him throughout his childhood, a target for bullies until he eventually went by Dory. His family were sharecroppers. By the age of 10, Dory was working the cotton fields alongside his brothers. The work was backbreaking. The pay was barely enough to survive. When he turned 20, Dory made a decision that thousands of black men were making across the South.

He would join the military, not because he loved his country, though he did. Not because he dreamed of adventure, though perhaps he did, but because it was one of the only ways a black man in Texas could earn a steady wage and escape the poverty trap of sharecropping. On September 16th, 1939, Dory Miller enlisted in the United States Navy at Dallas, Texas.

He reported to the Naval Training Station in Norfolk, Virginia for basic training. And that’s where he learned the truth about his new career. The Navy would feed him. The Navy would pay him. But the Navy would not train him to fight. The United States Navy in 1941 was not integrated.

It was segregated by design, by policy, and by conviction. Since 1919, the Navy had restricted black enlistes exclusively to the Mesman branch, later renamed the stewards branch to sound more dignified. The work was the same, cooking, cleaning, and serving white officers. This wasn’t an oversight. This was intentional. Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels had institutionalized the policy during World War I, arguing that white sailors would refuse to serve alongside black sailors as equals.

The close quarters of a ship, he claimed, made integration impossible. Black men could serve, but only in positions that made them invisible, subservient, and non-threatening. By 1940, out of 139,000 enlisted sailors, only 4,07 were black, less than 3%, and every single one of them was a messman or steward. The irony was bitter and obvious.

Black men could cook the food that fueled battleships. They could serve the officers who commanded those ships, but they could never command themselves. They could load ammunition into magazines, but they couldn’t be trusted to fire the guns. The Navy’s position was simple. Black men lacked the intelligence, discipline, and courage for combat roles.

Dory Miller knew this. Every black sailor knew this. Miller reported to the USS West Virginia, a Colorado class battleship and one of the most powerful vessels in the Pacific Fleet on January 2nd, 1940. He was assigned as a mess attendant third class. His duties were enumerated clearly, serve meals to officers, maintain officer quarters, handle laundry, polish brass, and stay out of the way when real sailors were working.

He was not trained on damage control. He was not trained on firefighting equipment, and he was certainly not trained on the ship’s anti-aircraft batteries. The 050 caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine guns that dotted the West Virginia’s deck were complex weapons. They required training to operate, training in loading, aiming, managing barrel overheating, and clearing jams.

The Navy had entire manuals dedicated to their proper use. Dory Miller had never been allowed to read those manuals. He had never been assigned to a gun crew. He had never fired a single round. But he had watched. During his two years aboard the West Virginia, Miller had observed the gun crews during drills. He’d seen how they loaded the ammunition belts.

He’d watched how they adjusted for target movement, and he’d noticed how the guns overheated after sustained fire. He wasn’t supposed to be learning these things. His attention was supposed to be on the officer’s breakfast orders. But Dory Miller had the mind of a fighter, and fighters study everything.

December 7th, 1941, 7:55 a.m. The first wave of Japanese aircraft appears over Aahu. Dory Miller is below deck, still collecting laundry from sleeping officers. The ship is at modified condition three, a minimal readiness state appropriate for a Sunday morning in a harbor 7,000 mi from the nearest combat zone.

3 minutes earlier, the USS Ward had fired on and sunk a Japanese submarine attempting to enter the harbor. The report was received, logged, and dismissed as unlikely. 2 minutes earlier, two army privates at the Opana Point radar station had detected a massive formation of aircraft approaching from the north. They were told not to worry about it, probably just B7s coming in from the mainland.

At exactly 7:55 a.m., Lieutenant Commander Mitsuo Fuida gives the order. Tora, Tora, Tora, Tiger, Tiger, Tiger. The signal means total surprise has been achieved. The first torpedo hits the USS West Virginia at 7:56 a.m. Then another, then another. Seven torpedoes in total will strike the ship in the next 8 minutes.

Each one carries over 400 lb of explosives. The blasts tear through the hull below the waterline, opening massive holes that flood the lower compartments instantly. Dory Miller feels the ship shudder beneath his feet. The lights flicker. He hears shouting, then screaming, then the general alarm. General quarters. General quarters. All hands to battle stations.

This is not a drill. Miller races toward his assigned battle station, the anti-aircraft battery magazine amid ships. But the passageways are flooding. Oil contaminated water is rushing up through the deck plates. Men are trapped below, drowning in darkness. He can’t reach his station. The route is blocked. So he does what he was trained to do in exactly zero scenarios.

He makes a decision. He heads topside. The scene on the main deck is apocalyptic. The USS Arizona, morowed just ahead, has been hit by an armor-piercing bomb that penetrated her forward magazine. The explosion, equivalent to 1,000 tons of TNT, has killed 1,177 men in an instant. The USS Oklahoma is capsizing, trapping over 400 sailors inside.

The USS California is listing badly, taking on water from multiple torpedo hits. Burning fuel oil spreads across the harbor surface, creating a sea of fire. The West Virginia is sinking. Miller emerges into chaos. Japanese dive bombers are screaming down through the smoke. Bullets from strafing zeros are ripping across the deck, sparking off the steel plating.

The ship is listing to port. Already 7° and increasing. And then Miller sees something that changes everything. Captain Mvin S. Benan, the West Virginia’s commanding officer, is lying on the navigation bridge, mortally wounded. A fragment from an armor-piercing bomb that hit the USS Tennessee mored directly alongside has torn through his abdomen.

Lieutenant Commander Dwis C. Johnson is trying to move the captain to a safer position, but Benan is a big man and Johnson can’t manage alone. Miller reaches them within seconds. “Help me get the captain below,” Johnson orders. Miller doesn’t hesitate. Together, they lift Captain Benion and try to carry him toward the Conning tower, but the captain knows he’s dying.

He knows the ship needs leadership, not sentiment. “Leave me,” Ben orders. “Get this ship fighting.” They place him in a sheltered position. Miller looks at the dying captain, a white man who has never eaten a meal Miller didn’t serve him, who has never spoken to him except to give orders. And then Miller makes the second decision that will define this day.

He looks for a weapon. The 50 caliber Browning machine gun is a devastating weapon. Developed by John Browning in 1918, it fires rounds the size of a man’s finger at 2,900 ft pers. A single bullet can punch through an aircraft engine block. The gun weighs 84 lb. It fires 450 to 600 rounds per minute. It can reach targets over a mile away, and it requires extensive training to operate effectively.

Dory Miller has received exactly zero hours of training on this weapon. Lieutenant Frederick H. White, the ship’s communications officer, finds Miller standing near an unmanned anti-aircraft gun on the navigation bridge. The gun crew is dead. The officer who commanded this position is dead. White is frantically trying to maintain communications with other ships, coordinate damage control, and keep the West Virginia from capsizing.

He needs every available hand. He looks at Miller, a messman trained to serve food, and makes a calculation that violates every regulation in the Navy book. “Can you operate this?” White asks, gesturing to the gun. Miller looks at the weapon. He’s watched the gun crews operate it during drills dozens of times. He knows the basic mechanics.

Load the belt. Pull the charging handle. Aim with the ring sight. Fire in controlled bursts to prevent overheating. I think so, sir. Miller responds. White doesn’t have time to second guess. Then get on it. Miller takes position behind the gun. He grabs an ammunition belt, 100 rounds of 050 caliber armor-piercing incendry ammunition, and feeds it into the receiver.

He pulls the charging handle back, chambering the first round. The Japanese are making their runs. Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers are circling for second runs. ID3A Val dive bombers are screaming down at 45° angles, releasing bombs at the last possible second before pulling up. Mitsubishi A6M0 fighters are strafing anything that moves.

Miller tracks a dive bomber through the ring site. He’s never done this before, but his body knows the rhythm. Lead the target. Compensate for speed. Squeeze. Don’t pull. He opens fire. The gun roars. The recoil pounds into Miller’s shoulders. Brass casings eject in a stream, clattering onto the deck. Tracers arc upward through the smoke.

Every fifth round burning bright orange to mark the path. He can see his rounds connecting. The dive bomber waivers, smoke trailing from its engine. It doesn’t matter that he’s never been trained. It doesn’t matter that the Navy thinks he’s not intelligent enough for this job. In this moment, Dory Miller is exactly what the United States Navy needs, a warrior.

Witnesses would later struggle to agree on details. Some said Miller shot down two planes. Some said four. Some said he definitely destroyed aircraft. Others said he damaged them severely, but couldn’t confirm kills. The official Navy report filed weeks later would settle on vague language. Miller manned a machine gun and fired at Japanese aircraft until ordered to abandon ship.

But the men who were there, the men who watched a messman transform into a gunner, they knew what they saw. Lieutenant Commander Johnson would later state, “Miller’s actions were clearly above and beyond the call of duty.” Miller fires until the ammunition runs out. He loads another belt. He fires until that runs out. He loads a third belt.

The gun barrel is glowing red from the sustained fire. The Navy manual says you’re supposed to change barrels after 75 rounds. Miller has fired over 300. The Japanese aircraft are pulling back now, forming up for the withdrawal. The first wave attack has lasted just 30 minutes. It feels like hours. At 8:25 a.m., Lieutenant White gives the order Miller has been dreading. Abandoned ship.

The USS West Virginia has taken seven torpedoes and two bombs. She settled onto the harbor bottom. Her main deck a wash. If they stay aboard, they’ll go down with her. Miller looks at Captain Benion one final time. The captain is dead. So are 105 other members of the crew. Miller helps carry wounded sailors across the gang way to the USS Tennessee.

He makes multiple trips, hauling men who can’t walk, supporting men who can barely breathe through oil soaked lungs. When the last wounded man is evacuated, Miller finally crosses to the Tennessee himself. His uniform is soaked with oil and blood, some his, most belonging to others. His hands are burned from the overheated gun.

His shoulders will be bruised for weeks from the recoil. He has no idea that in the next few hours a second wave of Japanese aircraft will arrive. He has no idea that 2,43 Americans will die today. He has no idea that the United States will enter World War II tomorrow. And he has absolutely no idea that he’s about to become a national hero.

In the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the American press explodes with coverage. Every newspaper from New York to Los Angeles runs the story. The attack dominates radio broadcasts. President Roosevelt’s Day of Infamy speech is heard by 60 million Americans. But there’s one story that doesn’t appear in the initial coverage.

The story of a messman who manned a gun. The Navy’s official reports mention acts of heroism by named officers and sailors. They detail the damage to each ship. They provide casualty figures. But for three months, the Navy doesn’t mention Dory Miller by name. Not because they don’t know what he did. Multiple officers witnessed it. Lieutenant Commander Johnson specifically recommended him for recognition.

But because acknowledging Miller’s actions creates a problem for the Navy’s entire racial policy. If a black messman with zero training can effectively operate an anti-aircraft gun in combat, then what’s the justification for excluding black sailors from combat roles? If a black man can make life or death decisions under fire, can lead evacuation efforts, can perform with courage and effectiveness, then what’s the excuse for segregation? The Navy doesn’t have good answers to these questions.

So, initially they simply don’t ask them. But the black press isn’t willing to let the story die. The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most influential black newspapers in America, begins investigating. They hear rumors from sailors returning from Pearl Harbor. They hear whispers about an unnamed messman who became a hero. In March 1942, 3 months after the attack, the courier breaks the story.

They don’t have Miller’s name yet, but they have the essential facts. A black messmanned a machine gun and shot down Japanese aircraft. The headline reads, “Mstery hero of Pearl Harbor sought.” The story spreads through black communities like wildfire. Here finally is a hero who looks like them. Here is proof that black Americans can fight, can serve, can sacrifice with the same courage as anyone else.

The pressure on the Navy becomes enormous. Civil rights organizations demand the sailor be identified and recognized. Black newspapers launch campaigns. Letters flood the Navy Department. Finally, on March 12th, 1942, the Navy relents. They announce the mystery hero’s identity, mess attendant, secondclass Doris Miller.

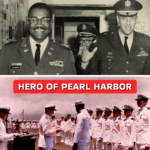

The misspelling of his name, Doris, instead of Dory, will persist in Navy records and newspaper coverage. But Miller doesn’t care about the name. He cares about the recognition. On May 27th, 1942, nearly 6 months after Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester W. Nimttz pins the Navy Cross on Dory Miller’s chest aboard the USS Enterprise.

The Navy Cross is the second highest decoration for valor that the Navy can award, ranking just below the Medal of Honor. Only 347 Navy crosses were awarded during the entirety of World War II. Dory Miller is the first black recipient. Admiral Nimttz reads the citation for distinguished devotion to duty, extraordinary courage, and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the fleet in Pearl Harbor, territory of Hawaii by Japanese forces on December 7th, 1941.

The citation is careful. It doesn’t specify how many aircraft Miller shot down. It doesn’t emphasize that he operated weapons he wasn’t trained to use. It doesn’t mention that he did all this while the Navy’s official position was that black men couldn’t handle combat roles. But the medal says what the words won’t.

The Navy sends Miller on a war bond tour. He appears at rallies across the country. His image appears on posters encouraging black Americans to enlist, to buy bonds, to support the war effort. Above and beyond the call of duty, the posters proclaim, showing Miller’s face beside the Navy cross. The irony is crushing. The Navy is using Miller to recruit black sailors.

Sailors who will still be restricted to the steward’s branch. Sailors who will still face segregation, discrimination, and exclusion from combat roles. Miller sees the contradiction clearly. In interviews, he’s diplomatic, but pointed. I would like to be able to do more than I am doing. I had hoped that I would get a commission and go to work directly with Negro personnel.

The Navy denies his request. Instead, they send him back to serve as a messman. In 1943, Miller is assigned to the USS Liskam Bay, an escort carrier heading to the Pacific Theater. He’s still a mess attendant first class, the highest rank available to black sailors at the time. On November 24th, 1943, the Liskum Bay is operating near Machinatal in the Gilbert Islands.

The ship is providing air support for Marines fighting ashore. At 5:13 a.m., a Japanese submarine I175 fires a single torpedo. The torpedo strikes the Liskam Bay’s bomb magazine. The resulting explosion tears the ship in half. She sinks in just 23 minutes. 644 sailors die. Only 272 survive. Dory Miller is among the dead.

In 1973, 30 years after his death, the Navy names a Noxcl class frigot in Miller’s honor, USS Miller FF1091. It’s the first major warship named after a black sailor. In 2020, the Navy announces that a Gerald R. Ford class aircraft carrier, the most advanced warship ever built, will be named USS Doris Miller, CVN81. When commissioned, it will be the first aircraft carrier named for a black American and the first named for an enlisted sailor.

But Miller’s legacy extends far beyond ships bearing his name. The pressure created by Miller’s story and the thousands of stories like his forced the Navy to confront its racial policies. In 1942, the Navy began accepting black recruits for general service, not just the steward’s branch. In 1944, the first black officers were commissioned, the Golden 13.

In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. The Navy officially ended all racial restrictions in 1949. These changes didn’t happen because the Navy suddenly developed a conscience. They happened because men like Dory Miller made segregation indefensible.

Miller proved what black Americans had been arguing for decades, that courage, intelligence, and ability have nothing to do with skin color, that when given the opportunity, black servicemen could perform any role with excellence. He proved it in the most dramatic way possible, under fire in the worst naval disaster in American history.

With the survival of his ship hanging in the balance, but Miller’s story also illuminates the painful contradictions of American military service. He was good enough to fight for his country. He wasn’t good enough to be treated as an equal while doing it. He was celebrated as a hero. He was denied the commission he requested.

He was sent back to serve food while white sailors with less courage commanded ships. He saved lives at Pearl Harbor. He died in obscurity 22 months later on a ship most Americans have never heard of. Some historians have argued that Miller deserved the Medal of Honor, not just the Navy Cross. His actions on December 7th certainly met the criteria.

Conspicuous gallantry above and beyond the call of duty at risk of life. But in 1942, the Navy wasn’t ready to award its highest honor to a black messman. The symbolism would have been too powerful, the implications too challenging to the existing order. Miller never publicly complained about this.

He understood the game being played. He understood that his heroism was useful to the Navy when it served their recruitment goals. and inconvenient when it challenged their segregation policies. Today, black Americans serve at every level of the US Navy. They command ships, fly aircraft, lead SEAL teams.

They serve as admirals and master chief petty officers. They are submariners, aviators, surface warfare officers, and yes, they operate the weapon systems that defend the fleet. None of this was possible in 1941. All of it became inevitable after December 7th, 1941. Dory Miller was 24 years old when he died aboard the Liskam Bay. He served his country for 4 years.

He was a hero for exactly 23 minutes, the duration of time between his first shot and the order to abandon ship. But those 23 minutes changed everything. They changed how America thought about black servicemen. They changed what was possible for future generations. They proved that when the crisis comes, heroism doesn’t check the color of your skin.

The official Navy report says Miller manned a machine gun and fired at Japanese aircraft. That’s technically accurate, but it misses the point entirely. Dory Miller didn’t just man a gun. He manned a position that the Navy said he wasn’t qualified to hold. He performed a role the Navy said he wasn’t intelligent enough to learn. He demonstrated courage that the Navy said his race didn’t possess.

He did it without training, without preparation, without permission. And he did it so well that the Navy had no choice but to recognize it. On December 7th, 1941, a mess attendant from Waco, Texas, proved something that should never have needed proving. That heroism isn’t a matter of rank or race.

That courage doesn’t require permission. And that sometimes the most important battles aren’t fought against the enemy in front of you. They’re fought against the limitations others have placed on you.

News

CH2 How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany…

CH2 Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies

Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies The morning air over the Solomon Islands carried…

CH2 Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart

Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart Bismarck Sea, March 3rd, 1943. At precisely 0600 hours,…

CH2 Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting In…

CH2 How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter

How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter The De Havilland Mosquito shouldn’t have worked….

End of content

No more pages to load