How an Oklahoma Farm Boy’s Secret Weapon Turned Hitler’s Panthers into Burning Metal Coffins – The Secret Shells They Weren’t Supposed To Have

December 26th, 1944 — the forest outside Bastogne lay under a white shroud of snow and smoke. The air was sharp with cordite and frost, and Technical Sergeant James Robert Caldwell could feel both burning the back of his throat. Inside his M10 Wolverine tank destroyer, the cold metal walls sweated with condensation. The engine throbbed behind him like a heartbeat buried in steel.

Through the periscope, Caldwell saw them — three German Panther tanks crawling out of the treeline, their gray hulls camouflaged with branches, their guns already hunting. The snow around their treads steamed. Each one moved with the deliberate confidence of something that had killed before and would kill again.

The order in his headset was unmistakable: “Charlie Company, disengage and fall back. Those are Panthers. You are outgunned.”

Private Danny Morrison, his nineteen-year-old loader from Detroit, looked up from the ammunition rack. “You heard ‘em, Sarge. They say to pull out.”

But Caldwell didn’t move. He kept his eye to the sight. Down in the valley, he could see the aftermath of the German breakthrough — a convoy of burning American trucks, black smoke curling against the snow. Men were crawling in the drifts, silhouettes twisting in agony. The smell of diesel, cordite, and flesh carried even up here.

He thought of his father’s voice, the way he’d said rules are written by men who never went hungry. He’d said it when they patched farm tools with wire and scrap during the Dust Bowl, when survival meant breaking the rulebook. Caldwell’s thumb brushed the trigger guard.

“Loader,” he said quietly. “That special round. Load it.”

Morrison hesitated. “The new one? You sure?”

“Load it.”

Morrison reached for a shell that wasn’t on any Army inventory sheet — one Caldwell had been machining himself in secret for three weeks, stealing hours after curfew and swapping favors with depot mechanics who didn’t ask too many questions. It gleamed dull gray under the faint light, its base marked by a small hand-scratched cross.

If it worked, it could save every man down there. If it didn’t, it could blow them all to pieces.

The Panther in the lead halted. Its gun traversed toward the road below. The barrel tilted, finding a target. Caldwell whispered, “Steady…” and nudged the elevation wheel. The sight lined up perfectly — turret ring, left side, about six hundred yards.

He exhaled slowly and pressed the trigger.

The M10 bucked. The shell screamed through the cold air and slammed into the Panther with a noise like thunder caught in steel. For half a heartbeat, nothing happened. Then a black plume erupted from the tank’s turret…

Continue below

December 26th, 1944. The frozen hills outside Bastonia, Belgium. Technical Sergeant James Robert Caldwell pressed his eye against the gunner’s scope of his M10 tank destroyer and watched three German Panther tanks emerge from the treeine like steel predators, hunting wounded prey. His hands trembled, not from cold, but from what he was about to do.

In the cramped metal coffin that passed for a fighting compartment, his loader, Private Danny Morrison, waited with a shell that wasn’t supposed to exist. The radio crackled with direct orders from battalion command to hold fire and withdraw. Enemy armor was too heavy. Engagement would be suicide.

But Caldwell had seen the column of American trucks burning on the road below, heard the screams of wounded men trapped in the snow, and he knew that following orders meant watching good soldiers die. His finger moved to the trigger. In that moment, Caldwell knew disobeying could end his career or save hundreds of lives trapped in the pocket below.

What headquarters didn’t know was that the shell Morrison held wasn’t standard issue. It was something Caldwell had been secretly manufacturing for 3 weeks in direct violation of ordinance regulations. Something that would prove German Panthers weren’t invincible after all. James Robert Caldwell grew up in rural Oklahoma during the depression. The second son of a wheat farmer who lost everything in the Dust Bowl.

His childhood was defined by making things work with nothing, fixing tractors with bailing wire, stretching food through long winters. His father taught him that rules were written by people who never went hungry and that survival meant trusting your hands more than someone else’s words.

When Caldwell enlisted in April of 1942, he wasn’t running toward glory. He was 23 years old, unmarried with calloused hands and a high school education that emphasized practical mathematics over poetry. The recruiter in Tulsa looked at his application and saw cannon foder. Cordwell saw three meals a day and a chance to send money home to his younger sister. Basic training at Fort Knox revealed an unexpected talent.

While other recruits struggled with ballistics calculations, Cordwell could estimate trajectory and armor penetration angles in his head. A skill born from years of calculating seed dispersal patterns and irrigation flows. His instructors noticed but didn’t care much. Gunnery sergeants wanted men who could follow firing solutions, not question them.

He was assigned to the tank destroyer force trained on the M10 Wolverine air thinly armored tracked vehicle mounting a 3-in gun designed to ambush German armor. His crew mates in Charlie Company, 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion, called him Oki with the casual cruelty of young men far from home.

They saw a quiet farm boy who read technical manuals during poker games and sketched modifications to ammunition in the margins of his field notebook. Nobody took him seriously until France. The 776th arrived in Normandy in July of 1944, 6 weeks after D-Day when the Bokeage country had become a meat grinder of hidden German positions and narrow killing lanes. Caldwell’s first combat engagement lasted 11 seconds.

A German Panzer 4 emerged from behind a hedger row at 80 yards. His commander screamed to fire. Caldwell fired. The standard M79 armor-piercing shell struck the Panza’s frontal armor and bounced off like a stone skipping on water, leaving only a bright scar on the German steel. The Panza’s return shot missed by inches. They escaped only because a P-47 Thunderbolt strafed the German tank minutes later.

That night, shaking in his foxhole, Cordwell began to understand the terrible mathematics of tank warfare. The M10’s 3-in gun was adequate against older German armor, but increasingly outmatched by newer models. Intelligence reports spoke of a new German tank called the Panther with sloped frontal armor that could deflect nearly any American shell.

Standard doctrine said tank destroyers should use speed and ambush tactics, hitting enemy armor from the flanks or rear where armor was thinner. But Caldwell had seen the Bokeage country. There were no long sight lines, no room to maneuver. When you met a panther, it would be face to face at point blank range, and the crew with the better shell would go home.

He started collecting duds, examining failed penetrations, measuring the angle of deflection on recovered German armor plates. His commander, Lieutenant Howard Brennan, a Virginia tobacco farmer’s son, told him to stop wasting time and focus on the job. Caldwell nodded and continued his research in secret.

By autumn of 1944, the Panther had become the nightmare that haunted every American tank crews dreams. Introduced in 1943 after the Germans faced Soviet T34s at Kusk, the Panther mounted a 75 mm gun that could penetrate American Shermans from 1500 yd while its own sloped armor deflected American shells even at close range.

Intelligence estimates suggested Germany had produced over 6,000 Panthers by late 1944. They appeared everywhere from the Italian mountains to the French plains, mechanical killers that turned American armor advantages into funeral pers. The standard American response involved massive numerical superiority, typically five Shermans to kill one panther, accepting horrific losses to achieve victory through attrition.

Tank crews called it the Ronson effect after the cigarette lighter that bragged it lit first time every time. American tanks burned first time every time. The Sherman’s gasoline engine and ammunition storage made it particularly vulnerable. A Panther could sit hull down behind a ridge and destroy an entire American column before taking a single hit. The US Army knew this was a problem.

Ordinance departments tested various solutions, including high velocity armorpiercing rounds with tungsten carbide cores designated M93 HVAP. These experimental shells could penetrate panther armor, but tungsten was desperately scarce, needed for machine tools and aircraft engines. Production was limited to a few thousand rounds per month, distributed primarily to elite units with political connections.

The 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion received exactly zero HVAP rounds through official channels. They were expected to fight Panthers with the same shells that bounced off Panza 4s. The frustration built through September and October as Caldwell’s unit pushed toward the German border. They lost three tank destroyers to Panthers in ambushes where American crews never got off an effective shot.

Each funeral service deepened Caldwell’s conviction that men were dying because regulations valued tungsten for factory machinery over soldiers lives. He began writing letters to ordinance depots requesting technical specifications for HVAP manufacturer. Most went unanswered. One sympathetic supply officer at a forward depot sent him a single cutaway training round used for demonstrating internal construction to gunnery students with a note saying it was all he could spare.

Caldwell studied that training round like a medical student examining a cadaavver. The HVAP design was elegantly simple. Tungsten carbide penetrator surrounded by an aluminum sabot that fell away after leaving the barrel. The tungsten core being denser than steel maintained velocity better and concentrated force on a smaller impact area. The challenge was manufacturing.

Tungsten carbide required industrial equipment and precision machining. But Caldwell noticed something the designers perhaps hadn’t considered. The penetrator didn’t need to be pure tungsten carbide. It just needed to be harder and denser than the steel shell casing it replaced. And while tungsten carbide was rare, tool steel wasn’t.

Every machine shop in every rear echelon motorpool had tool steel used for cutting bits and lathe tools. It wasn’t as hard as tungsten carbide, but it was significantly harder than the mild steel used in standard shells. If he could manufacture a penetrator from tool steel and fit it into a standard shell casing, he might create something between a standard AP round and a true HVAP round. Not perfect, but better than nothing.

The technical challenges were substantial. He needed to machine cylindrical penetrators to precise dimensions, remove the standard penetrator from existing shells without destroying the explosive burster charge, insert the modified penetrator, and ensure the shell would still fire without exploding in the barrel. He had no lathe, no mill, no formal authorization, and no training in ammunition modification.

What he had was a mechanicallyincclined loader named Danny Morrison, a former auto mechanic from Detroit, and access to a maintenance depot outside Mets, where sympathetic motorpool sergeants looked the other way when men borrowed equipment after hours. They started in early November.

Morrison located a damaged lathe in a salvage pile, one the motorpool had written off as too worn for precision work. They repaired it with parts cannibalized from two other wrecked machines. Caldwell drew detailed specifications based on the training round, calculating dimensions that would maintain the shell’s balance while maximizing penetrator mass.

They needed tool steel blanks. Morrison found them by trading cigarettes and whiskey to a maintenance sergeant whose machinists used tool steel cutting bits. Each blank took 6 hours to machine into a penetrator on their rebuilt lathe, working in 2-hour shifts after duty hours, while Morrison stood watch for officers.

The work was exhausting and dangerous. One penetrator shattered during machining, sending steel fragments into the wooden wall behind the lathe. Another spun off center and nearly broke Coldwell’s wrist. But gradually they developed a process. By late November, they had produced 32 modified shells, each one carefully marked with a small scratch on the base to distinguish it from standard ammunition. Testing was impossible.

Firing unauthorized ammunition without approval could result in court marshal. Caldwell couldn’t exactly request a panther for target practice. Instead, he relied on mathematical models and desperate hope. His calculations suggested the tool steel penetrator should increase penetration by perhaps 15 to 20% over standard shells. Whether that would be enough to defeat Panther armor depended on range, angle, and luck.

He and Morrison loaded the modified shells into their tank destroyer’s ready rack, placing them in specific positions where Cordwell could identify them by touch in the chaos of combat. Lieutenant Brennan noticed the scratched markings during an inspection. Cordwell told him it was a personal identification system to track ammunition expenditure.

Brennan, who had learned to trust his gunner’s competence, if not his methods, accepted the explanation without pressing further. The rest of Charlie Company remained unaware that their battalion’s most reliable crew was carrying homemade ammunition that violated at least a dozen ordinance regulations. They stored the shells and waited.

November passed into early December. The battalion moved into reserve positions in Luxembourg, a quiet sector where the brass expected nothing to happen. The men played cards, wrote letters home, and dreamed of Paris leave. Caldwell used the time to produce 18 more modified shells, pushing their infantry to an even 50. Morrison joked that if they survived the war, Caldwell could start an ammunition company.

Caldwell didn’t laugh. He could feel something building in the cold December air. A tension that reminded him of Oklahoma thunderstorms gathering on the western horizon. December 16th, 1944, the German army launched Operation Watch on the Rine.

Say a massive offensive through the Arden’s forest aimed at splitting the Allied armies and capturing the vital port of Antworp. Three German armies, including elite Panzer divisions with hundreds of Panther and Tiger tanks, smashed through thinly held American positions in what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. The 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion received emergency orders to move north and reinforce the collapsing front.

They drove through freezing rain and snow, past columns of American troops retreating in disorder, past burning vehicles and abandoned equipment. The radio traffic was chaotic, filled with panicked reports of German armor breaking through everywhere of entire American units surrounded and cut off. By December 20th, Caldwell’s company had reached the outskirts of Bastonia, a crucial crossroads town that the Germans desperately needed to capture.

The American 101st Airborne Division held Bastonia, surrounded by German forces, fighting off constant attacks. The 776th’s mission was to keep the roads open for supply convoys trying to reach the besieged paratroopers. It was a mission that guaranteed contact with German armor.

Panthers were everywhere in the Ardens, leading the assault spearheads, crushing American resistance with mechanical efficiency. The first engagement came on December 22nd. Cordwell’s crew, positioned in a treeine covering a crossroads, spotted two panthers moving along a ridgeel line 800 yd away. The range was too long for a reliable shot with standard ammunition, suicidal at that distance.

Lieutenant Brennan ordered them to hold fire and wait for the Germans to close, but the Panthers stopped at the ridge and began firing at American positions in the valley below. Cordwell watched through his scope as high explosive shells destroyed two supply trucks and killed at least a dozen men. The Panthers weren’t closing.

They were using their range advantage exactly as German doctrine prescribed. Caldwell made a decision. He loaded one of his modified shells and fired without waiting for orders. The shell covered 800 yd in less than 2 seconds, struck the lead Panther’s turret ring at a slight angle, and penetrated. The Panther didn’t explode dramatically. It simply stopped moving as the crew bailed out through the hatches, smoke pouring from the interior.

The second Panther reversed rapidly behind the ridge line and disappeared. Lieutenant Brennan demanded to know what ammunition Caldwell had used. Cordwell told him the truth, expecting immediate arrest. Instead, Brennan stared at him for a long moment and said they would discuss it later if they survived. Then he ordered Caldwell to load more of the modified shells.

They had just proved that homemade ammunition could kill panthers at ranges where standard shells were useless. The word spread through the battalion faster than official communications. Hather crews heard that Caldwell’s destroyer had knocked out a Panther at 800 yd, something nobody thought possible with an M10’s 3-in gun. Men started asking questions.

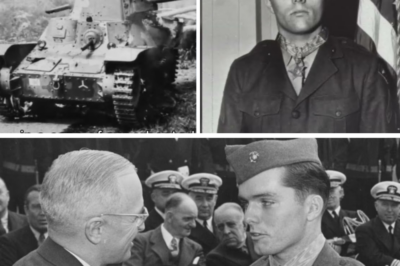

Where did the ammunition come from? Could they get some? Caldwell found himself in the strange position of being simultaneously in violation of regulations and the most popular gunner in the battalion. The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Randall, a West Point graduate who valued results over protocol, called Caldwell to his command post on December 23rd. Caldwell expected a court marshal.

Instead, Randall asked him to explain the technical specifications of his modified shells. Caldwell laid out the mathematics, the metallurgy, the manufacturing process. Randall listened without interruption, then asked the critical question. How many had Caldwell produced? 50 shells. Randall did the calculation silently.

50 shells divided among the battalion’s 36 tank destroyers meant each crew could have one, maybe two special rounds for emergency use. Not enough to change the campaign, but enough to give individual crews a fighting chance against Panthers. Randall made a command decision that would have ended his career if it backfired.

He ordered Caldwell to teach the modification process to selected mechanics in each company. They would manufacture more shells using the same methods Caldwell had developed. It was completely unauthorized, a violation of ordinance protocols, and absolutely necessary. December 24th, Christmas Eve, the weather cleared enough for Allied aircraft to fly support missions, but the ground situation remained desperate.

German forces were pushing toward the Muse River, and Bastonia was still surrounded. The 776th received orders to support a task force trying to break through to the besieged paratroopers. Cordwell’s crew, now equipped with 73 modified shells after a frantic manufacturing session, moved into position, covering the main road from the south.

Intelligence reported at least a company of Panthers, approximately 14 tanks defending the approach routes to Bastonia. The American relief column included light tanks, armored infantry, and the tank destroyers. Against 14 Panthers, it was still a desperate gamble. The attack began at dawn on December 25th. Within minutes, German Panthers emerged from concealed positions and began destroying American vehicles with methodical efficiency.

Caldwell’s destroyer, positioned on a slight rise overlooking the road, engaged targets at ranges between 400 and 900 yd. The modified shells performed beyond expectations. Where standard ammunition would have bounced harmlessly off the Panther’s frontal armor, the tool steel penetrators punched through, creating catastrophic damage inside the German tanks.

Cordwell fired 17 rounds in 43 minutes, scoring 11 confirmed penetrations on seven different Panthers. Three Panthers burned completely, their ammunition cooking off in spectacular explosions. Four others were disabled and abandoned by their crews. Morrison loaded shells with mechanical precision, his Detroit mechanic’s hands steady despite the chaos.

The loaders compartment filled with acurid smoke from the breach, spent casings piled around their feet. The radio filled with voices shouting fire missions, casualty reports, desperate calls for support. The breakthrough to Bastonia succeeded partly because Caldwell’s destroyer eliminated the Panther strong point that should have stopped the relief column.

Other tank destroyers in the battalion, now equipped with varying numbers of modified shells, contributed to the victory. By noon on December 25th, forward elements of the fourth armored division, reached the 101st Airborne’s positions. The siege was broken, but the battle was far from over. German forces continued attacking throughout late December and early January, trying to regain momentum.

Cordwell’s crew fought in a dozen more engagements, using their modified ammunition to engage Panthers at ranges the German crews thought were safe. The psychological impact was significant. German tankers, accustomed to American shells bouncing off their armor, suddenly found themselves vulnerable at extended ranges. Some German commanders began withdrawing their Panthers from forward positions, reducing their effectiveness as breakthrough weapons. By mid January, when the Bulge was finally eliminated and American forces resumed their

offensive into Germany, the 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion had manufactured and expended over 400 modified shells. The confirmed kill count against Panthers and other heavy German armor was 73 vehicles destroyed or disabled. Compared to the typical 5:1 loss ratio when American forces engaged Panthers with standard ammunition, it was a revolutionary improvement.

The official investigation began in late January when an ordinance inspector discovered the modified shells during a routine ammunition inventory check. The inspector, a buy the book captain from a depot unit who had never heard hostile fire, wanted immediate courts marshal for everyone involved.

He filed a report citing violations of ammunition safety protocols, unauthorized modification of ordinance, misappropriation of military materials, and conduct prejuditial to good order. The report went up the chain of command where it encountered a different reality. Field commanders who had watched Caldwell’s innovation save lives and wind battles had zero interest in prosecuting the men responsible.

Lieutenant Colonel Randall submitted a counter report documenting the modified shell’s effectiveness, including testimony from dozens of crewmen whose lives had been saved by the improved ammunition. He pointed out that the army’s failure to provide adequate antipanther ammunition to frontline units had created the necessity for field expedient solutions. Either punish the men who solved the problem or fix the supply system that created it.

The matter escalated to theater headquarters where it landed on the desk of a general who understood that good publicity was hard to find in the winter of 1945. Prosecuting innovative soldiers for saving American lives would be a public relations disaster. The general made the problem disappear. No courts marshall, no official reprimands.

Instead, a quiet directive went to ordinance departments instructing them to increase HVAP ammunition production and distribution to frontline units. Caldwell received a bronze star for valor in combat, with the citation carefully emitting any reference to homemade ammunition. The real recognition came from his fellow soldiers who knew the truth. The modified shells became legendary within the tank destroyer community.

Other units experimented with similar field modifications, though none achieved the same success as Caldwell’s original design. By March of 1945, improved ammunition from official sources finally reached frontline units in significant quantities, making field modifications unnecessary.

But for those crucial weeks in the Ardens, when American forces were desperately fighting to stop the German offensive, Caldwell’s innovation had provided a critical advantage. The war in Europe ended in May of 1945. Cordwell returned to Oklahoma in November, discharged as a master sergeant with two Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart from a shell fragment wound received during the final push into Germany.

He married his high school sweetheart that Christmas, bought a small farm with his military savings, and never spoke publicly about the modified shells. Danny Morrison went back to Detroit, opened an auto repair shop, and occasionally told customers about the war when they asked about the scar on his left forearm. Lieutenant Brennan returned to Virginia and his tobacco farm, maintaining correspondence with Caldwell for 40 years.

They met once in 1963 at a 776th Battalion reunion in Washington. Brennan, by then a successful businessman, told Caldwell that disobeying orders to hold fire on December 26th had been the right decision. Caldwell responded that he hadn’t disobeyed. He had interpreted the order to hold fire as guidance subject to tactical revision based on ground conditions.

They both laughed at the distinction without difference. The technical legacy of Caldwell’s improvisation appeared in unexpected places. In 1953, the Army’s Ordinance Corps published a field manual on expedient ammunition modifications for use in future conflicts. The manual included a section on field manufactured penetrators using available tool steel with specifications remarkably similar to Cordwell’s original design.

The manual didn’t credit Caldwell by name, but veterans who read it recognized the source immediately. The broader lesson was taught at West Point and other militarymies as a case study in tactical innovation. Officers learned that rigid adherence to doctrine in the face of battlefield reality was a recipe for defeat.

They studied how a farm boy from Oklahoma with no formal engineering education had solved a problem that stumped ordinance experts by trusting his practical experience over official specifications. The story became part of the cultural knowledge passed down through generations of tank crews. A reminder that survival often depended on individual initiative rather than institutional support.

Lieutenant Colonel Randall, who had authorized the widespread manufacturer of modified shells despite the regulatory risks, was promoted to full colonel and later wrote a memoir that devoted an entire chapter to the Bastonia ammunition crisis. He argued that military regulations existed to serve the mission, not the other way around, and that commanders who lacked the courage to bend rules when necessary had no business leading men in combat.

Caldwell lived to be 87 years old, dying in 2003 in the same Oklahoma farmhouse where he was born. His obituary in the local newspaper mentioned his military service, but focused mainly on his contributions to the farming community and his 57-year marriage. The detail about the modified shells appeared in the second to last paragraph, a brief mention that he had developed improved ammunition during the Battle of the Bulge.

But among veterans of the 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion and their families, the story was told and retold. Morrison’s grandson, researching his family history, discovered technical drawings in his grandfather’s papers, showing the exact specifications for the modified penetrators.

He donated the drawings to the National Archives where they reside today, available to researchers studying American ammunition development during World War II. Several of the modified shells recovered from battlefield positions decades after the war are displayed in military museums as examples of field expedient engineering.

The plaques beside the exhibits explain how one sergeant’s refusal to accept inadequate equipment saved countless lives and changed American anti-armour tactics. The shells themselves are unremarkable looking standard 3-in cases with small scratch marks on the base. But to anyone who understands their history, they represent something larger than metallergy.

They represent the moment when individual courage and practical intelligence overcame institutional failure. The final irony is that Cordwell never considered himself a hero. In interviews conducted late in his life by military historians, he consistently deflected credit, insisting that Morrison deserved equal recognition for the manufacturing work that Lieutenant Brennan had shown real courage in authorizing continued use of the shells, that the real heroes were the men who fought in the snow and died in burning tanks.

He maintained that he had simply applied basic mechanical principles learned on an Oklahoma farm to a military problem. The shells worked because tool steel was harder than mild steel, a fact known to any machinist. The innovation wasn’t in the science, but in the willingness to act without permission when permission would have arrived too late.

When asked why he had risked court marshal to develop unauthorized ammunition, Caldwell gave an answer that summarized his entire philosophy. He said that men were dying because the people who wrote procurement regulations had never watched friends burn alive in disabled tanks. Rules were important, but they weren’t more important than the lives of the men fighting the war. Someone had to make that decision on December 26th, 1944.

And he happened to be in the right position with the right skills to do something about it. If that made him a hero, then being a hero was just another word for doing your job when nobody else could. What shattered the invincibility of German panthers wasn’t advanced technology developed in secret laboratories or brilliant tactical innovations from military academicians.

It was scratched base shells manufactured on a salvaged lathe by men who trusted their hands more than regulations. It was a sergeant from Oklahoma who understood that sometimes the most sophisticated response to a complex problem is basic physics applied with courage.

It was the recognition that institutional competence couldn’t replace individual initiative. That survival often depended on the willingness to break rules written by people who would never face the consequences. The mathematics of victory in the Ardens were written not in official afteraction reports, but in the scratch marks on homemade shells that turned German panthers into burning metal coffins.

73 confirmed kills, 400 shells manufactured in violation of every ordinance protocol, hundreds of American lives saved because one man decided that disobedience was the highest form of duty. That calculation, more than any strategic plan or industrial production figure, revealed the truth about how wars are actually won. Not by the armies we wish we had, but by the soldiers we’re lucky enough to have when everything goes wrong.

What shocked you most about this story? Was it the courage to defy orders, the technical ingenuity of the solution, or the institutional failure that made such improvisation necessary? Comment below and share this forgotten piece of history with anyone who believes that following rules matters more than saving lives.

News

CH2 How a Single American Meal Shattered Japan’s Warrior Spirit and Rewired the Minds of Its POWs Forever

How a Single American Meal Shattered Japan’s Warrior Spirit and Rewired the Minds of Its POWs Forever June…

CH2 They Grounded Him for Being “Too Old” — Then He Shot Down 27 Fighters in One Week

They Grounded Him for Being “Too Old” — Then He Shot Down 27 Fighters in One Week March 3,…

CH2 ‘Let Them Try!’ He Laughed—the Day Hermann Göring Mocked America’s Promise To Build 50,000 Planes… And How Detroit Answered With 100,000

‘Let Them Try!’ He Laughed—the Day Hermann Göring Mocked America’s Promise To Build 50,000 Planes… And How Detroit Answered With…

CH2 Japanese Couldn’t Stop This Marine With a Two-Man Weapon — Until 16 Bunkers Fell in 30 Minutes

The 19-Year-Old MARINE Who Turned a Two-Man Bazooka Into a 30-Minute Massacre on Iwo Jima’s ‘Meat Grinder’ Hill The…

CH2 How This ‘COWSHED AIRFIELDS’ Fooled Göring’s Luftwaffe and Turned the Battle of Britain Into the Greatest Illusion in Military History

How This ‘COWSHED AIRFIELDS’ Fooled Göring’s Luftwaffe and Turned the Battle of Britain Into the Greatest Illusion in Military History…

CH2 How a U.S. Farm-Boy’s “Shovel Trap” Captured 43 Germans in One Night

How a U.S. Farm-Boy’s “Shovel Trap” Captured 43 Germans in One Night The moon that night was a pale…

End of content

No more pages to load