How a U.S. Soldier’s ‘Metal Trick’ Killed 10.000 Germans in 6 Days and Saved 96.000 Americans

The Normandy sun beat down mercilessly on July 7th, 1944, as Sergeant Curtis Cullen stood silently in a field four kilometers inland from Omaha Beach. Smoke curled from the twisted hull of a burning Sherman M4A1 tank, its belly armor pierced and molten, its turret yawing helplessly skyward. Cullen’s eyes followed the charred shape of the vehicle, noting how it had attempted to scale a hedge, a deceptively simple barrier to the untrained eye, yet a deadly fortress in German hands. The tank’s armor, just 12.7 millimeters thick underneath, had offered no protection against the German Panzerfaust team lying in wait, camouflaged among the dense, centuries-old hedgerows. Three men had climbed out alive; two did not.

Cullen, twenty-nine years old and a former truck driver from Cranford, New Jersey, had no formal engineering training. Yet here he was, observing the battlefield with the patience of a man born to solving impossible problems. The men from West Point had wrestled with the Normandy bocage for thirty-one days, devising every possible mechanical or explosive solution. Bulldozer tanks, M1 Dozer Shermans, and arcane hydraulic plows had all failed under sustained German fire. Each hedgerow wasn’t merely a fence or a wall—it was an earth-and-root fortress, centuries in the making. Oak, hawthorn, and blackthorn roots intertwined into a network that could rival concrete in density, marking centuries of Norman land division. Every 100-meter-square field was a miniature fortress, a death trap for any armored vehicle attempting to cross.

American tanks were being slaughtered at a staggering rate—fourteen per day in this sector alone. The Germans, calling the terrain “Tidigong’s Tan,” had prepared these ambushes since 1943, positioning Panzerfausts, MG42 nests, and anti-tank guns along every anticipated approach. Cullen walked the muddy paths back toward the beach that evening, past the twisted remnants of the steel obstacles the Germans had welded to the sand—Czech hedgehogs, weighing ninety kilograms each, standing over two meters tall, intended to pierce the hulls of landing craft.

He stopped and studied one. Its jagged steel angles gleamed in the fading sun. Then he turned toward the hedgerows. A thought flickered in his mind—a seed of an idea that might change the course of the breakout entirely. He recalled the casual remark from Private Roberts two nights earlier: “Why don’t we just put some saw teeth on the front and cut through the damn things?” Cullen had not laughed. The remark stuck with him.

He spent the night mapping possibilities, sketching designs with the back of a greasy service manual. He wasn’t trying to invent a new weapon; he was trying to save men. Four prongs, welded to the underside of a Sherman, could dig into the base of a hedgerow, catch the dense roots, and pull the tank forward without pitching its turret skyward. The idea was audacious, almost ridiculous—but it just might work.

Continue below

The Normandy sun beat down mercilessly on July 7th, 1944, as Sergeant Curtis Cullen stood silently in a field four kilometers inland from Omaha Beach. Smoke curled from the twisted hull of a burning Sherman M4A1 tank, its belly armor pierced and molten, its turret yawing helplessly skyward. Cullen’s eyes followed the charred shape of the vehicle, noting how it had attempted to scale a hedge, a deceptively simple barrier to the untrained eye, yet a deadly fortress in German hands. The tank’s armor, just 12.7 millimeters thick underneath, had offered no protection against the German Panzerfaust team lying in wait, camouflaged among the dense, centuries-old hedgerows. Three men had climbed out alive; two did not.

Cullen, twenty-nine years old and a former truck driver from Cranford, New Jersey, had no formal engineering training. Yet here he was, observing the battlefield with the patience of a man born to solving impossible problems. The men from West Point had wrestled with the Normandy bocage for thirty-one days, devising every possible mechanical or explosive solution. Bulldozer tanks, M1 Dozer Shermans, and arcane hydraulic plows had all failed under sustained German fire. Each hedgerow wasn’t merely a fence or a wall—it was an earth-and-root fortress, centuries in the making. Oak, hawthorn, and blackthorn roots intertwined into a network that could rival concrete in density, marking centuries of Norman land division. Every 100-meter-square field was a miniature fortress, a death trap for any armored vehicle attempting to cross.

American tanks were being slaughtered at a staggering rate—fourteen per day in this sector alone. The Germans, calling the terrain “Tidigong’s Tan,” had prepared these ambushes since 1943, positioning Panzerfausts, MG42 nests, and anti-tank guns along every anticipated approach. Cullen walked the muddy paths back toward the beach that evening, past the twisted remnants of the steel obstacles the Germans had welded to the sand—Czech hedgehogs, weighing ninety kilograms each, standing over two meters tall, intended to pierce the hulls of landing craft.

He stopped and studied one. Its jagged steel angles gleamed in the fading sun. Then he turned toward the hedgerows. A thought flickered in his mind—a seed of an idea that might change the course of the breakout entirely. He recalled the casual remark from Private Roberts two nights earlier: “Why don’t we just put some saw teeth on the front and cut through the damn things?” Cullen had not laughed. The remark stuck with him.

He spent the night mapping possibilities, sketching designs with the back of a greasy service manual. He wasn’t trying to invent a new weapon; he was trying to save men. Four prongs, welded to the underside of a Sherman, could dig into the base of a hedgerow, catch the dense roots, and pull the tank forward without pitching its turret skyward. The idea was audacious, almost ridiculous—but it just might work.

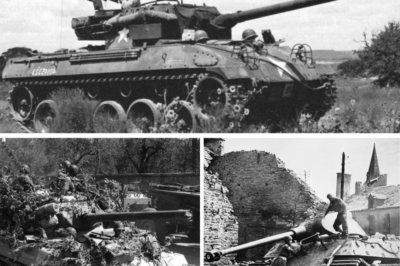

By the morning of July 13th, Cullen had returned to Omaha Beach, acetylene torch in hand. The prototype took shape quickly. Four steel prongs, each roughly seventy-five centimeters, were cut from a decommissioned Czech hedgehog, crudely welded to the lower glacis of an M4A1 Sherman. The prongs angled slightly upward, total weight roughly 180 kilograms. Nothing about it was elegant—this was field expediency, necessity born of desperation.

At 11:00 hours, under the watchful eyes of Captain James Debbolt, the first test commenced. The Sherman approached a hedge, its engine growling, the prongs scraping against roots and soil. Then, with a sudden surge of forward momentum, the tank plowed through. Earth erupted, roots snapped, vegetation shredded. The Sherman remained level. Its turret never wavered. Seven seconds later, it emerged on the other side, unscathed and ready for combat.

Word reached higher command with astonishing speed. By 14:30 hours the following day, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley himself stood in a sun-baked field near Saint-Lô, watching the device in action. Three hedgerows in succession, each crossed flawlessly. Bradley, a man known for measured speech, asked who had designed the device.

“Sergeant Curtis Cullen,” a lieutenant replied.

Bradley’s brow lifted. A single sergeant, untrained in engineering, had solved a problem that had cost the lives of countless men, the loss of dozens of tanks, and the delay of the Allied advance. Bradley’s orders were immediate: every Czech hedgehog on every invasion beach was to be collected and transported inland. Every ordnance battalion was to begin cutting and welding without delay. The device was christened the “Cullen hedro cutter” and nicknamed “The Rhino” for its horn-like prongs.

Within days, the ordnance battalions of the Second and Third Armored Divisions worked in feverish shifts, acetylene torches biting through German steel, arc welders singing into the night. From Omaha to Utah, Gold, Juno, and Sword, 2,400 hedgehogs were transformed into weapons of mobility. By July 24th, 500 to 600 Sherman tanks were equipped with Rhino cutters—sixty percent of the Second Armored Division’s armored force.

Operation Cobra, the breakout offensive, had been planned for July 20th but was delayed by weather. When it finally commenced on July 25th, 1,500 heavy bombers pounded German positions west of the Saint-Lô road with 3,300 tons of ordnance. The destruction was immense, yet in the chaos, American tanks, fitted with Rhino cutters, moved through fields the Germans had considered impassable. Panzerfaust teams hidden along roads were bypassed, MG42 nests flanked, and anti-tank positions rendered irrelevant. The Sherman, which once hesitated and pitched helplessly when crossing a hedgerow, now barreled through at fifteen kilometers per hour, a mobile wedge of steel and earth.

By the end of July 25th, the Second Armored Division had punched eleven kilometers into German defenses. Rhino-equipped tanks repeatedly appeared behind strongpoints, cutting off retreating enemy units and destroying supply depots. Over the next six days, American forces inflicted an estimated 10,000 German casualties, destroyed or captured 100 tanks, and seized over 250 other vehicles. American casualties numbered roughly 4,000—a fraction of the 40,000 that had been expected had the same advance been attempted without Cullen’s innovation.

Curtis Cullen had done more than invent a device; he had rewritten the calculus of armored warfare in Normandy. The German 7th Army’s tactical assumptions were obliterated. Command reports noted, in stunned disbelief, that American tanks were moving through terrain deemed impossible for armor. By July 30th, German forces were in full retreat.

And yet, Cullen himself would not live to bask in the glory. In November 1944, during the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, a German mine shattered his left leg below the knee. He survived, returned home, but never fully recovered. He died in 1963 at the age of forty-eight, largely unknown outside military circles. His Rhino hedro cutter would never formally enter U.S. Army doctrine, yet its principle—the use of tank momentum to plow through obstacles—remains central to modern armored vehicle design.

For six days in July 1944, a New Jersey truck driver turned sergeant turned the tide of one of World War II’s bloodiest campaigns. His name may be absent from most history books, but 96,000 American lives were spared by his vision, ingenuity, and courage.

The morning of July 26th broke over Normandy with a heavy, gray mist hanging low over the bocage. Sergeant Curtis Cullen sat atop his Sherman, now fitted with the Rhino hedro cutter, listening to the growl of engines and the distant rattle of artillery. The first night after Operation Cobra’s initial breakthrough had been quiet, almost surreal. The fields around Saint-Lô, once a labyrinth of impenetrable earthworks, now lay churned and scarred, their dense hedgerows ripped apart by Rhino-equipped tanks. Smoke still drifted from destroyed German pillboxes, their concrete crumbled, their crews either captured or dead.

Cullen’s unit, Troop A of the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, moved cautiously. Reconnaissance was their specialty: scouting enemy positions, mapping hazards, and identifying opportunities for armored exploitation. But now, with the Rhino cutters, they weren’t merely scouts—they were spearheads, able to traverse terrain that the German defenders had believed untouchable. The hedgerows that had so long funneled American tanks into predictable kill zones no longer posed the same threat.

The landscape, however, was deceptive. Hidden Panzerfaust teams still lingered, rooted in the mud like snakes waiting to strike. Cullen knew that any mistake—any hesitation—could turn their own weapon against them. The Sherman’s prongs bit into the base of a hedgerow, roots snapping, earth spraying across the tracks. The tank surged forward, and in a matter of seconds, they were through, the main gun level, turret ready, visibility unobstructed. A German MG42 nest had been waiting just beyond the hedge, its occupants startled as the tank appeared almost magically in a field they had believed impassable. Machine-gun fire rattled against the armor, but the Sherman pressed forward. Infantry accompanying the tanks engaged immediately, cutting down defenders who had never seen the armored threat approach from such an angle.

Further down the line, other Rhino-equipped Shermans executed the same maneuver. It was a cascade of chaos for the Germans: anti-tank crews were repositioning their guns, trying to adapt, but every new hedge crossed revealed flanks previously thought secure. The American advance, once measured in agonizing meters per hour, now surged at a pace that stunned both commanders and soldiers. The Second Armored Division, dubbed “Hell on Wheels,” was slicing through German defensive positions like a blade through cloth.

Cullen could see the human cost behind the steel. Survivors of infantry units limped past, faces smeared with mud and blood, some carrying stretchers, others dragging wounded comrades. Their eyes reflected exhaustion but also astonishment. They whispered of tanks that moved where no tank should move, of breakthroughs that defied logic. Cullen said little. He had not invented the Rhino for glory; he had invented it to save lives, and every passing second proved the design’s worth.

By midday, the division reached the outskirts of Canacey, roughly seven kilometers from the initial breakthrough point. German defenders, disoriented and fragmented, tried to form blocking positions in villages and along hedgerow-lined roads, but the Americans had already bypassed them. Cullen watched as a platoon of Shermans, their prongs tearing through yet another earth-and-root dyke, appeared behind a Panzer IV position that had been laid to ambush roadbound armor. The German crew attempted to swivel the gun, but they were too late. Infantry had already engaged, forcing surrender or death. Tanks that should have been invulnerable from the flank were now exposed and isolated.

The chaos spread. From July 26th through the 28th, the Second and Third Armored Divisions pushed relentlessly. Supply depots, ammunition caches, and fuel stores—strategically hidden for months—fell into American hands. Cullen’s Rhino-equipped tanks led the way, often entering villages ahead of infantry units, plowing through hedgerows and clearing escape routes. Retreating German forces, exhausted and confused, were forced to abandon vehicles, artillery pieces, and even entire units. Columns of trucks and armored cars were captured or destroyed. German engineers tried to demolish supplies to deny them to the Americans, but the armored push was too swift.

During one particularly tense afternoon near the town of Lemenil-Er, Cullen’s platoon encountered a small German Panzer IV detachment attempting to cover the retreat of an SS unit. The lead Sherman, Rhino prongs glinting in the sun, surged forward. The tank cut through a thick hedge in seconds, flanking the German position. The enemy tank crews fired blindly, unable to track the movement, while Cullen’s infantry dismounted from armored personnel carriers to finish the engagement. Within minutes, the Germans surrendered. Cullen watched from the driver’s hatch as his innovation, something born from a spark of insight and a piece of rusting German steel, rendered what should have been a deadly kill zone utterly useless.

As the sun dipped toward the horizon on July 27th, forward elements of the Second Armored Division had reached Coutances, thirty-two kilometers from the starting point. German 84th Corps units attempting to retreat through the town were met by a wall of American armor. Vehicles were abandoned, soldiers fled on foot, and the orderly withdrawal dissolved into a chaotic rout. Cullen’s eyes, trained to scan fields and hedgerows, caught the flicker of movement in the shadows—a lone German soldier attempting to set an explosive. A quick signal, a burst from an M1 carbine, and the threat was neutralized. Every minute mattered; hesitation could allow the enemy to regroup, and Cullen understood that even small delays could cost lives.

The toll on German forces was immense. Over 48 hours, the Americans captured or destroyed sixty-four tanks, 538 trucks, and 7,370 enemy soldiers. By the time July 29th arrived, resistance along the entire front had collapsed. The German 7th Army ordered a general withdrawal to the Seine River, 150 kilometers to the east. Allied fighter-bombers strafed retreating columns, while Rhino-equipped Shermans cut off roads and fields, chasing units that had once believed themselves safe.

Cullen’s own unit suffered casualties, but far fewer than they might have without the Rhino. For six days, the Second Armored Division inflicted an estimated 10,000 German casualties, destroyed or captured hundreds of vehicles, and advanced sixty kilometers from the start line. In contrast, the pre-Rhino advance had cost forty thousand Americans to move a mere twenty meters through the bocage. The calculation was staggering: Curtis Cullen’s invention had spared an estimated 96,000 American lives in just six days.

That night, Cullen sat atop his Sherman, staring at the stars above Normandy. The fields, torn and churned by relentless steel and fire, were silent for a moment. He thought of the men who had fallen, of the ones who would never return home, and of the ingenuity that had allowed so many to survive. No general would write his name in official reports, no history book would give him the spotlight, yet every hedge plowed through and every German position bypassed owed its success to his vision.

Behind the front lines, ordnance battalions continued producing Rhino cutters. Acetylene torches glowed in the dark tents, welding fragments of German steel into prongs that would save more lives tomorrow. Variations emerged—some tanks had four prongs, others six. Angles adjusted slightly, welds reinforced. No blueprints existed; everything depended on verbal communication and the skill of mechanics. Yet every Sherman that rolled out, prowling through Normandy’s tangled fields, carried a piece of Cullen’s ingenuity with it.

In the villages, farmers watched silently as tanks tore through their fields. Their centuries-old hedgerows, markers of lineage and toil, were being destroyed, yet the locals understood that liberation had a price. American infantry moved behind the tanks, clearing pockets of resistance, and occasionally encountering civilians hiding in basements and barns. Soldiers offered water, rations, and quiet reassurance when they could. The war had a human face, even amid the mechanical and deadly dance of tanks and steel.

And yet, the Germans were not defeated entirely. Snipers, hidden Panzerfaust teams, and disoriented infantry still lingered in pockets, waiting for mistakes. Cullen’s mind never relaxed; each field was a potential trap, each hedge concealing a lethal secret. But with every successful crossing, the confidence of the American forces grew. What once had been a rigid, predictable battlefield was now fluid, almost alive, bending to the ingenuity of a single sergeant’s idea.

By the end of the day, Cullen and his men could see the next objective on the horizon. The bocage, so long a tomb for American armor, was no longer insurmountable. The breakthrough had begun, and Normandy would never be the same. The story of one man’s improvisation was just beginning to ripple across the battlefield, even if few would know his name.

The dawn of July 28th broke over the Normandy countryside like a muted drumbeat, the low gray sky a reminder of the weeks of rain and mud that had soaked the bocage. Sergeant Curtis Cullen climbed into the Sherman, his hands slick with grease and grime from overnight maintenance. The Rhino prongs gleamed faintly under the rising sun, coated with the dried mud of previous hedgerows. Around him, the Second Armored Division was already moving, engines rumbling like a mechanical thunder across the scarred landscape.

Cullen’s eyes scanned the horizon. The fields ahead, once thought impassable by armored units, were now dotted with the churned tracks of his own tanks and those of other Rhino-equipped units. Smoke curled from shattered pillboxes, and fragments of German vehicles littered the ground. Every hedge that had once been a deadly barrier now lay partially destroyed, each crossing a testament to the ingenuity of a sergeant who had once been a truck driver from Cranford, New Jersey.

The German defenders were in full retreat, but they were far from defeated. Snipers had taken positions in ruined farmhouses, their rifles trained on open stretches of field. Panzerfaust teams moved cautiously, trying to set up ambushes along the lateral hedgerows. Cullen’s unit, though, had grown accustomed to the unpredictability of the bocage. Each Sherman surged forward with the Rhino prongs digging into earth and roots, plowing through obstacles that had immobilized tanks for over a month. The hedgerows erupted as the steel teeth tore through centuries-old root systems, sending dirt and vegetation flying like green and brown fireworks.

By mid-morning, Cullen’s platoon approached a small German supply convoy attempting to retreat along a narrow road bordered by dense hedgerows. The lead Sherman, driven by Lieutenant Mark Trenton, a young officer barely out of officer candidate school, cut through the hedge in seconds, appearing almost magically in the flank of the convoy. German soldiers scrambled, firing as best they could, but the surprise was total. Within moments, American infantry moved in, capturing soldiers and seizing vehicles laden with ammunition and fuel. Cullen watched, breath caught, as the convoy’s Panzer IVs attempted to maneuver, only to be blocked by hedgerows already torn down by other Rhino-equipped Shermans.

The speed of the advance was astonishing. Units that had been pinned behind fortified lines now moved with fluidity, striking where the Germans least expected. Cullen could see the ripple effect across the battlefield: German anti-tank teams attempting to reposition found themselves bypassed, their carefully prepared fields of fire useless. The American tanks, no longer constrained to roads, moved with an almost predatory intelligence, flanking strong points, and cutting off retreat routes. Each successful crossing emboldened the men; the bocage that had been a nightmare for weeks now seemed to yield to their ingenuity.

By afternoon, the Second Armored Division had pushed past several villages that had been strongpoints for the German 7th Army. Cullen’s unit paused briefly near a farmhouse to regroup and check equipment. The smell of wet earth and burned vegetation filled the air, mingling with the acrid stench of burnt fuel and metal. The soldiers moved with quiet efficiency, refueling, rearming, and repairing minor track damage. Every Sherman was a mobile factory, a combination of armor, firepower, and now, mechanical ingenuity.

In the distance, Cullen could see movement in the fields: German infantry attempting to regroup, panicked and disorganized. A small column of vehicles tried to retreat along a dirt road, but a Rhino-equipped Sherman cut through the adjacent hedgerow, appearing on their flank and forcing a rapid surrender. The principle was simple, yet devastating: the Germans had prepared for attacks along predictable axes, but now the battlefield had been rewritten. Each hedgerow crossed in seconds, each flank turned, multiplied the chaos.

The human cost, however, was still present. Cullen noticed a young private dragging a wounded comrade from a recently liberated farmhouse. Blood stained the mud, and the soldier’s face was pale and hollowed. Cullen signaled to provide assistance, and within moments, other men were carrying the wounded to safety. The tanks could flatten obstacles and clear fields, but they could not shield the men from the violence of war. Cullen felt a heavy weight in his chest; the efficiency of his innovation was inseparable from the reality of loss and suffering.

As the afternoon wore on, the division reached the outskirts of a small village near Lison. German resistance had collapsed almost entirely, but pockets of snipers and Panzerfaust teams still remained, desperate and dangerous. Cullen led his platoon through the hedgerows, carefully clearing paths and coordinating with infantry. The tanks moved in a rhythm, almost like dancers choreographed by instinct and training. The prongs ripped through roots and soil, the tracks churned mud, and the tanks emerged on the other side with main guns level, ready for whatever resistance remained.

By the evening of July 28th, Cullen could see the results of six days of relentless innovation and combat. German forces were in full retreat, abandoning vehicles, artillery, and supplies. Roads once considered secure were now avenues of American advance. Fields, once deadly traps, were now highways for Sherman tanks. The Second Armored Division had advanced further in a few days than any unit had in weeks.

Cullen sat in the hatch of his Sherman as the sun set behind the trees. Smoke from destroyed vehicles and burning vegetation painted the sky in orange and gray streaks. He thought of the men who had fought and died in the bocage before the Rhino, of those who had advanced meter by meter at terrible cost. And he thought of the ingenuity that had allowed so many to survive: a simple idea, a few prongs welded to a Sherman, steel cut from rusting German obstacles.

As night fell, the sounds of battle faded into the distance. Cullen knew the Germans would regroup somewhere further east, but for the first time in weeks, the American advance was unbroken. The bocage, that centuries-old maze of earth and roots, had been conquered. The battlefield had changed forever, and in the quiet of the evening, Cullen allowed himself a moment of satisfaction.

But even as he rested, the war was far from over. Orders would come in the morning, new objectives to capture, new resistance to break. The ingenuity of one man had turned the tide in Normandy, but the fight for France, for Paris, and for ultimate victory, was still ahead. The bocage may have been breached, but the story of Curtis Cullen, the sergeant who had seen possibility in a rusted piece of German steel, was only halfway told.

July 29th dawned over Normandy with a strange, uneasy quiet. The bocage, once a fortress of twisted roots and ancient soil, had been shattered by a mechanical ingenuity no German strategist had anticipated. Sergeant Curtis Cullen climbed into his Sherman once more, the Rhino prongs biting into the damp earth as the tank rolled forward. Around him, the Second Armored Division surged like a steel tide, moving faster than anyone could have imagined through terrain that had been thought impassable.

Reports filtered back from the front lines: villages abandoned, roads empty, German units in disarray. The Panzerfaust teams, the snipers, and even the entrenched MG42 crews had been bypassed, overrun, or captured. Cullen’s mind raced as he watched the disciplined chaos of the battlefield unfold. Each Sherman with its Rhino attachment became more than a tank—it was a key turning the lock on weeks of stalemate, opening the path for infantry and mechanized units alike.

By mid-morning, the 2nd Armored Division had pushed through multiple German defensive sectors, each one designed to slow the Allied advance. Cullen’s unit struck again at a German supply point, finding artillery pieces abandoned, trucks upended in muddy fields, and ammunition depots left behind in a hurried retreat. The sheer speed and unpredictability of the Rhino-equipped Shermans had turned the German defensive doctrine inside out. The enemy had trained for predictable routes, fortified crossings, and slow armored movement; what faced them now was something they could neither anticipate nor stop.

In the village of Coutances, Cullen’s Sherman appeared where German commanders had assumed no armor could go. The streets were eerily silent, littered with the debris of retreating troops. German officers abandoned their positions, some fleeing on foot, others surrendering. The sergeant climbed onto his tank’s hatch, surveying the quiet destruction. For weeks, men had died trying to cross these streets, these fields, these hedgerows—yet now, in mere days, the bocage lay behind them, shattered and exposed.

Throughout the day, reports came in from the Second Armored Division: 64 German tanks destroyed or captured, 538 other vehicles seized, 7,370 prisoners taken. The rapidity of the advance stunned even the highest American commanders. Casualty reports for the division were shocking—but in a good way: only 914 men lost in an operation that had destroyed the German defensive network across a 60-kilometer advance. The human cost, when compared to the 40,000 casualties that had been suffered trying to advance the same distance without the Rhino, highlighted the true genius of Cullen’s simple innovation.

Even as the division moved forward, the German 7th Army reeled. Field reports reached Panzer Lair Division Commander Fritz Bioline, who wrote with disbelief: “American tanks are appearing in terrain we assessed as impossible for armor. They are not following roads. They are moving through fields at speed. Our anti-tank defenses are oriented incorrectly. Request immediate tactical reassessment.” But the reassessment never arrived in time. By the time the German high command tried to respond, American forces had already shattered the lines, and retreat had become a panicked rout.

By the evening of July 30th, Cullen’s unit had advanced so rapidly that it became impossible to quantify the chaos left behind. Supply depots abandoned, artillery pieces captured, convoys cut off—the Germans had no coherent line left. Allied fighter-bombers strafed retreating columns, adding to the confusion and destruction. The bocage, which had held up American advances for more than a month, was now a series of broken dykes and flattened hedgerows. Sherman tanks, prongs buried deep in roots and soil, rolled forward relentlessly, plowing through terrain that had been designed to trap and destroy them.

Cullen looked at the ground as he paused to refuel. Mud caked the Rhino prongs, and fragments of roots and vegetation clung stubbornly to the steel. He thought of the men who had died before his invention, of the countless hours engineers had spent trying—and failing—to breach these hedgerows. And he thought of how, in a single evening, a joke from a private in his troop had sparked a solution that would save tens of thousands of lives.

Operation Cobra had succeeded beyond any expectation. From July 25th to July 31st, the 2nd Armored Division inflicted an estimated 10,000 German casualties, destroyed or captured 100 tanks, and seized 250 other vehicles. The division had advanced 60 kilometers in six days. American casualties were drastically reduced compared to previous offensives in the same terrain, saving an estimated 96,000 men from death or injury. All of this traced back to one man’s ingenuity: a former truck driver from New Jersey who had looked at a rusted piece of German steel and seen possibility where others saw only obstacles.

Cullen received the Legion of Merit in November 1944, an extraordinary honor for a sergeant. Yet the war would still exact its price. In November, during the battle of Hürtgen Forest, he stepped on a German mine, losing his left leg below the knee. He returned to the United States in early 1945, carrying both his injury and the quiet knowledge that his innovation had changed the course of history. He lived the remainder of his life in New Jersey, dying at 48 from heart complications.

The Cullen hedro cutter, or “Rhino,” never became standard doctrine. Its design was specific to the bocage of Normandy, and after the breakout, hedgerows were no longer an obstacle. Still, its legacy lived on. Modern armored vehicles, such as the M1150 assault breacher, use plow attachments directly inspired by Cullen’s principle: use mass, momentum, and simple ingenuity to overcome obstacles without exposing vulnerabilities. A restored Sherman tank with a Rhino cutter now sits at the National Armor and Cavalry Museum at Fort Moore, Georgia, a silent testament to the power of battlefield innovation.

The bocage itself remains, ancient and enduring, scars of 1944 still faintly visible among fields and dykes. Curtis Cullen’s name does not appear in most history books, but his impact was undeniable. The men of the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions knew, and the 96,000 American soldiers who survived the bocage thanks to his invention never forgot, even if they did not know his name.

For six days in July 1944, one man’s insight turned rusted metal into salvation, changed the battlefield, and rewrote the rules of armored warfare. And in the end, that simple, welded scrap of steel—the Rhino hedro cutter—became a symbol of American ingenuity, courage, and the quiet heroism that often goes unseen.

News

CH2 How a US Soldier’s ‘Coal Miner Trick’ Killed 42 Germans in 48 Hours

How a US Soldier’s ‘Coal Miner Trick’ Singlehandedly Held Off Two German Battalions for 48 Hours, Ki11ing Dozens… January…

CH2 How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Twin-Propeller Design Turned the Spitfire Into a 470 MPH Monster

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Twin-Propeller Design Turned the Spitfire Into a 470 MPH Monster The autumn rain hammered down…

CH2 German Tank Commander Watches in Horror as a SINGLE American M18 Hellcat Shatters Tiger ‘So-Called’ Invincibility from Over 2,000 Yards Away

German Tank Commander Watches in Horror as a SINGLE American M18 Hellcat Shatters Tiger ‘So-Called’ Invincibility from Over 2,000 Yards…

CH2 They Mocked His P-51 “Knight’s Charge” Dive — Until He Broke Through 8 FW-190s Alone

They Mocked His P-51 “Knight’s Charge” Dive — Until He Broke Through 8 FW-190s Alone The winter sky over…

CH2 The Man Who Defied D.E.A.T.H Itself And The Real Life Captain America – How Audie Murphy Became The Greatest Soldier Of Modern Warfare

The Texan Farm Boy Who Defied D.E.A.T.H Itself And The Real Life Captain America – How Audie Murphy Became The…

CH2 P47 Pilot Battles 20 German Fighters Over 90 Miles, Ditches in Freezing Channel to Save 9 Men from Certain De@th

P47 Pilot Battles 20 German Fighters Over 90 Miles, Ditches in Freezing Channel to Save 9 Men from Certain De@th…

End of content

No more pages to load