How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

April 1st, 1945. 23:47 hours. Private First Class Robert Chun crouched deep in a narrow foxhole on the southern perimeter of Kakazu Ridge, every sense straining against the darkness so complete he could not see his own hand six inches from his face. The air was thick with humidity and the smell of wet earth, mingled with the faint metallic tang of spent cartridges and the acrid residue of mortars fired hours earlier. He adjusted the M3 carbine across his lap, its weight heavy against his chest, a deliberate contrast to the standard M2 carbines issued to the rest of his platoon, which barely tipped the scales at five pounds. This was no ordinary rifle. Its stock had been fitted with a scope the size of a small telescope, bolted directly to the receiver, and a cable snaked from the scope to a battery pack strapped across his back. The lead-acid cells inside weighed thirteen pounds, identical to those found in an automobile. To those in his platoon, it had earned nicknames like “the car battery with a trigger” or, on less charitable days, “a science experiment destined to fail.”

The skepticism was understandable. For seventy-two hours straight, Japanese infiltrators had attacked the perimeter under the cover of darkness, exploiting every flaw in the American defensive line. In that time, the 96th Infantry Division had lost twenty-three men, and thousands of rounds had been fired into the night with minimal effect. Only seven enemy soldiers had been confirmed killed. Chun had been issued this experimental weapon system only four days prior. In all that time, he had fired it exactly zero times in combat. He did not know if the system would function under real conditions, whether the battery would hold its charge in the oppressive tropical humidity, or if he would live to see the first round find its mark. All he knew was that the Japanese were coming, and he could not see them.

The enemy understood the limitations of conventional firepower. In daylight, American artillery, naval gunfire, and air support could obliterate fixed defensive positions. The Japanese learned this lesson painfully at battles like Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima. But night offered them cover. Small groups, often between ten and fifty men, moved silently through the darkness, weaving between coral outcroppings, drainage ditches, tall grass, and shell-pocked terrain. Their rifles were ready, grenades strapped across their chests, and sometimes they carried satchel charges for close assaults on foxholes or machine-gun nests. The goal was always infiltration—strike before the defenders could react, then vanish into shadows before counterfire could be brought to bear.

American defenders were at a profound disadvantage. Flares helped, but their advantage was temporary and often came with a cost. The standard parachute flare burned at over 200,000 candlepower, illuminating a circle roughly three hundred yards in diameter. But the brilliance was blinding. Soldiers staring through the light had their night vision destroyed, leaving them effectively blind for thirty to forty-five seconds after the flare burned out. Japanese infiltrators knew this. They timed their attacks to coincide with the window of temporary American blindness, closing distance, shifting positions, or striking the line during moments when defenders’ senses were compromised.

Machine gunners did their best, firing into the black, tracing sounds, anticipating motion, but often hitting nothing at all. Panic was unnecessary, but the tension was palpable. The men of the 96th Infantry Division were exhausted. In seventy-two hours, they had lost thirty-four soldiers to nighttime infiltration, while an additional sixty men had become combat ineffective due to fatigue, stress, and the psychological toll of being under constant threat in near-total darkness. Every shadow became a potential attacker; every sound, a harbinger of death. The attrition was slowly grinding down the division.

Chun’s weapon, the experimental M3 carbine system, was designed to change all that. It had been developed in 1944 at the Engineer Research and Development Laboratories at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The concept was deceptively simple.

Continue below

April 1st, 1945. 23 47 hours. Private First Class Robert Chun crouched in a foxhole on the southern perimeter of Kakazu Ridge, staring into darkness so complete he could not see his own hand 6 in from his face. The M3 carbine across his lap weighed 28. The standard M2 carbine issued to every other man in the 96th Infantry Division weighed 5.2 pounds.

Chun’s rifle had a scope the size of a small telescope boated to the receiver. A cable ran from the scope to a battery pack strapped to his back. The battery weighed 13 lb. It contained lead acid cells identical to those used in automobile engines. The other men in his platoon called the weapon a car battery with a trigger. Some called it science fiction.

Some called it a waste of time. In the past 72 hours, Japanese infiltrators had killed 23 Americans on this ridge during night attacks. The defenders had fired thousands of rounds into the darkness. They had killed seven Japanese soldiers. Chun had been issued the M3 carbine 4 days earlier.

He had fired it exactly zero times in combat. He did not know if the system would work. He did not know if the battery would hold charge in the tropical humidity. He did not know if he would survive long enough to find out. What Chun did know was this. 150 soldiers in the 96th Infantry Division had been issued the same weapon system.

In the next 7 days, those 150 men would account for 30% of all Japanese casualties caused by rifle and carbine fire on Okinawa. But at 2347 hours on April 1st, 1945, Chun knew none of that. He only knew the Japanese were coming and he could not see them. The night attacks had begun the moment the 96th Infantry landed on Okinawa. The Japanese defenders understood American firepower. They had learned the lesson at Guadal Canal, Tarawa, Pelleu, Iwoima.

In daylight, American artillery and air support destroyed any force that held fixed positions. So, the Japanese attacked at night. Small groups, 10 to 50 men, moving through the darkness toward American lines. They carried rifles, grenades, sometimes satchel charges. They crawled through tall grass, through drainage ditches, between coral outcroppings. They moved silently.

When they reached the American perimeter, they either opened fire or detonated themselves against foxholes and gun positions. The tactic was effective because American defenders could not see the attackers until they were inside the defensive line. Flares helped but created their own problems.

A parachute flare burned at 200,000 candle power. It illuminated a circle roughly 300 yd in diameter for 25 seconds, but it also destroyed the night vision of every American soldier looking at it. When the flare died, defenders were blind for 30 to 45 seconds while their eyes readjusted. Japanese infiltrators used those 30 seconds to close distance or change position.

Machine gunners fired blindly into the darkness, spraying30 caliber rounds at sounds, at movement, at nothing. The 96th Infantry Division had been on Okinawa for 72 hours. In that time, they had lost 34 men to night infiltration. Medical personnel estimated another 60 men were combat ineffective due to exhaustion and stress from sustained nighttime combat without sleep.

The M3 carbine was supposed to change that. The weapon had been developed in 1944 at the Engineer Research and Development Laboratories at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The concept was simple. mount an infrared spotlight and an infrared sensitive scope on a rifle. The spotlight emitted invisible infrared light. The scope converted that infrared light into a visible green image.

A soldier using the system could see in complete darkness. The enemy could not see the infrared light. They could not see the soldier. They could not see the scope. They only knew they were being shot at when the bullet arrived. The US Army had manufactured approximately 1,700 M3 carbine systems during the war.

Approximately 150 had been sent to Okinawa in late March 1945. The 96th Infantry Division received a majority of those systems. The soldiers selected to use them had completed a 3-week training program. The training covered basic operation, battery maintenance, range estimation through the narrow field of view, and target identification. Chun had qualified on the system at a range near the invasion staging area.

He could identify man-sized targets at 70 yards in total darkness. he could hit those targets with three out of five rounds. The instructors told him the system would work in combat. They told him the battery would last 20 to 30 minutes of continuous use.

They told him the scope was fragile and the infrared spotlight was temperamental and the entire system required careful handling. Then they issued him five spare batteries and sent him to the front line. At 2351 hours, Chun heard movement southeast of his position, 60 yards out, maybe 70. The sound was faint, fabric against vegetation, a boot scraping coral. He could not see anything.

The moon was a thin crescent, less than 10% illuminated, obscured by clouds. Chun activated the M3 system. He flipped a switch on the battery pack. The pack hummed, a faint vibration against his spine. The battery was generating 4,250 volts to power the infrared spotlight and the image converter tube inside the scope. Chun shouldered the carbine and looked through the scope.

The field of view was narrow, roughly 10°. He had to scan slowly, sweeping left to right, searching for movement. At first, he saw nothing. Green gray static vegetation, rocks. Then he saw a shape. A man 65 yards southeast moving low to the ground. The figure appeared as a bright green silhouette against the darker green background.

Chun could see the man’s torso, his arms, the rifle across his back. The man was crawling forward, using a drainage ditch for cover. Chun watched. The man stopped, looked left and right, continued crawling. Behind him, two more shapes appeared. Three infiltrators moving in single file closing on the American perimeter. Chun adjusted his grip on the carbine.

The weapon was frontthe heavy. The scope and spotlight assembly added significant weight forward of the receiver. He braced the stock against his shoulder and controlled his breathing. The M3 carbine was select fire, semi-automatic or full automatic. Chun had been trained to use semi-automatic for precision shots beyond 50 yards.

He placed the green crosshairs on the lead infiltrator’s center mass. The man was 63 yd away, still crawling. Chun squeezed the trigger. The carbine fired. The muzzle flash was minimal, suppressed by a conical flashhider. The sound was sharp but not loud, muffled by the tropical vegetation. The lead infiltrator jerked, collapsed. The second man froze.

Chun worked the trigger again. The carbine fired. The second man dropped. The third man began to rise, trying to retreat. Chun fired a third time. The man fell backward into the drainage ditch. Three shots, three kills. The entire engagement lasted 9 seconds.

Chun scanned the area through the scope, searching for additional targets. He saw nothing. The drainage ditch was empty. The three bodies lay motionless. Chun kept the scope active, kept watching. His heart rate was elevated, but his hands were steady. This was different than range training. The targets had been shooting back.

At 00017 hours, Chun heard voices, Japanese voices, low and urgent, coming from the treeine 80 yard south. He scanned with the scope, found four men crouched behind a fallen tree, talking. They were looking toward the drainage ditch where the three infiltrators had died. One of them pointed, another shook his head. They were trying to understand what had happened. Their comrades had been killed by an enemy they could not see.

No muzzle flash, no tracer rounds, just three men dead in the darkness. Chun watched. He could hear them talking, but could not understand the words. The four men began moving not toward the American line, parallel to it, heading west, using the tree line for cover. They were relocating, searching for a different approach.

Chun tracked them through the scope. The narrow field of view forced him to pan slowly, keeping the green shapes centered. At 80 yards, they were at the edge of his effective range. He let them move. They disappeared into thicker vegetation. Chun deactivated the scope to conserve battery power.

The instructors had warned him 20 to 30 minutes of continuous use. Then the battery would need changing. He had been using the scope for 26 minutes. He shut it down, waited in the darkness. 5 minutes later, he heard movement again west of his position, 55 yd closer. He activated the scope. The battery hummed. He scanned left, found two shapes low to the ground, moving through tall grass.

The same four men had split into two pairs. These two were trying a flanking approach. Chun aimed at the lead man, fired. The man collapsed. The second man rolled sideways trying to find cover. Chun tracked the movement. Fired again. The man stopped moving. Two more kills. Chun shut down the scope. His battery indicator showed 40% charge remaining.

Not enough for another sustained engagement. He reached behind him and pulled a fresh battery pack from his pack. The battery swap required 15 seconds. Disconnect the cable from the old pack. Connect to the new pack. Secure the new pack to his back. He kept his eyes on the darkness while his hands worked by feel.

At 00034 hours, the battery was swapped. Chun reactivated the scope and resumed scanning. The Japanese adapted after the first engagements. They stopped using drainage ditches and tree lines for approach routes. They began moving through the most difficult terrain, areas thick with vegetation and coral outcroppings, where the M3 scopes narrow field of view became a liability.

Chun learned to compensate by positioning himself at elevated points with overlapping fields of fire. On the night of April 2nd, he moved to a position on a small rise 40 yard behind the main defensive line. The position offered better visibility of approach routes and allowed him to cover multiple sectors. At 0143 hours, he detected movement at 68 yds southsoutheast.

A single infiltrator moving slowly through thick undergrowth. Chun watched. The man stopped every few yards, listening, looking. He was cautious, experienced. He reached a clearing 12 feet wide, paused at the edge, scanned the area. Then he stepped into the clearing, and ran fast, head down, minimizing exposure time. Chun led the movement, fired.

The man dropped midstride. But as Chun scanned for additional targets, he saw something that made him pause. Three more shapes 85 yds out, moving toward the same clearing. They had been following the first man, using him as a scout. If the scout made it across the clearing without being shot, the others would follow. The scout had not made it.

The three men stopped at the treeine. One of them signaled. They changed direction, moving east, abandoning the clearing approach. Chun watched them disappear into the vegetation. The Japanese were learning that certain routes were compromised.

They were learning that an invisible enemy was watching, shooting, killing in the darkness. At 03 12 hours, Chun’s scope malfunctioned. He had been scanning continuously for 18 minutes when the image inside the scope began to flicker. Green static, then darkness, then green static again. The infrared spotlight was overheating.

The tropical humidity and sustained use that caused condensation inside the sealed unit. Chun shut down the system, waited 2 minutes for the spotlight to cool, reactivated. The image returned stable. He resumed scanning. This was the system’s primary vulnerability. The components were sensitive to temperature and humidity. The battery pack generated significant heat during operation.

That heat combined with the ambient temperature of 78° F and 85% humidity created condensation. The instructors had warned him. They had said the system was temperamental. They had said it required constant monitoring. Chan had learned to cycle the system on and off using short bursts of observation to minimize heat buildup.

At 0401 hours, he detected a larger group, seven men 73 yds southwest moving in a loose column formation. This was different. The previous infiltrators had moved in pairs or small groups. Seven men suggested a more aggressive push. Chun watched. The group stopped, formed a line, began advancing toward the American perimeter. They were 70 yards out, then 65, then 60.

Chun had to decide. Engage now and reveal his position or wait until they were closer and risk them getting inside his effective range. He decided to engage. He aimed at the center man in the line. Fired. The man dropped. The others scattered, diving for cover. Chun shifted aim. Fired at a second man. Hit. The remaining five began firing blindly toward the American line.

Their rifles cracked in the darkness. Muzzle flashes lit the night in brief yellow bursts. But they were firing at the wrong position. They were aiming at the main defensive line 40 yard ahead of Chun’s elevated position. Chun tracked the muzzle flashes through the scope. Each flash illuminated the shooter’s position for a split second.

He aimed at the nearest flash, waited for the shooter to fire again. The rifle cracked. Chun saw the green shape behind the flash, fired. The shape collapsed. He repeated the process. Wait for muzzle flash. Track the shape. Fire. Four more kills in 23 seconds. The Japanese fire stopped. Silence.

Chun scanned the area saw no movement. Seven infiltrators dead. Zero American casualties in his sector. By dawn on April 3rd, word of the M3 carbine’s effectiveness had spread through the 96th Infantry Division. Other operators reported similar results. Private Eugene Wilson had killed six infiltrators in a single engagement near Tombstone Ridge.

Corporal James Harkley had detected a 12-man infiltration group at 75 yards and directed machine gun fire to eliminate them before they reached the perimeter. The 150 M3 operators were functioning as force multipliers. They could see the enemy in total darkness. They could engage at ranges where the enemy believed they were invisible.

They could call in supporting fire with precise coordinates. The impact on Japanese tactics was immediate and measurable. On the night of April 3rd to 4th, Japanese infiltration attempts in sectors covered by M3 operators decreased by 62% compared to the previous night. The enemy was learning that certain areas were lethal.

After dark, they were learning that the Americans had developed a capability that negated the advantage of night movement. Japanese commanders began issuing new orders. Infiltrators were told to avoid open approaches. They were told to move more slowly, to use every available piece of cover, to assume they were being observed even in total darkness. Some units began conducting infiltrations during periods of rain or fog when visibility was reduced for all parties, but the M3 system still functioned in those conditions, though at reduced range. If this story has you hooked the way it grabbed us, hit that like button. It

tells YouTube to share this with people who need to hear it, and subscribe so you don’t miss what happens next. Back to Chun. On April 5th, Chun encountered the systems most significant limitation. He was positioned on the western approach to Kakazu Ridge covering a 120° sector with another M3 operator 80 yard to his right.

At 028 hours, heavy fog rolled in from the coast. Visibility dropped to less than 20 ft with the naked eye. Chun activated his scope and scanned. The infrared system could penetrate the fog better than visible light, but the effective range was cut in half. He could see shapes at 35 yd, maybe 40, but beyond that, the image degraded into gray static.

At 02 41 hours, he detected movement at the edge of his reduced visibility range. multiple shapes, at least 10, possibly more. They were advancing through the fog in a skirmish line. Chun fired at the nearest shape, hit the others continued advancing. They had realized the fog provided protection. Chun fired again, worked the trigger, fired repeatedly. He hit three more targets, but the remaining infiltrators were closing fast.

At 25 yards, they were inside his optimal engagement range, but still advancing. Chun switched the carbine to full automatic. The M3 carbine could fire 750 rounds per minute on full auto. He fired a sustained burst into the advancing line. The carbine emptied its 15 round magazine in less than 2 seconds.

He dropped the empty magazine, loaded a fresh one, fired another burst. The advancing infiltrators broke and scattered. Some retreated into the fog. Some went to ground. Chun scanned with the scope, found two shapes crawling away. Let them go. He had stopped the advance, but the engagement had cost him 29 rounds and nearly depleted his second battery. The fog lifted at 03 47 hours.

Chun counted seven Japanese bodies in the area he had engaged. Three more were found 15 yards from the American perimeter. The infiltrators had gotten closer than any previous group in his sector. The Japanese changed tactics again. On April 7th, infiltration groups began carrying flashlights, not to illuminate their own movement, but to blind the M3 operators.

At 0156 hours, Chun was scanning his sector when a bright white light suddenly flared 60 yards to his front. The light was pointed directly at his position. The intensity overwhelmed the M3 scope’s image converter tube. Chun’s view through the scope went completely white.

He shut down the system, looked with his naked eyes, saw the flashlight beams sweeping back and forth, searching for targets. The tactic was clever. The Japanese had realized the Americans were using some kind of optical system. They were trying to blind it. Chun grabbed a fragmentation grenade from his belt, pulled the pin through.

The grenade arked through the darkness and detonated 12 ft from the flashlight position. The light went out. Chun waited 10 seconds for his scope’s image tube to reset, then reactivated the system, scanned the area, found one body near the flashlight, found two more shapes retreating east. He tracked one, fired. The shape dropped. The second shape disappeared into vegetation.

The flashlight tactic had been partially effective. It had temporarily blinded the M3 scope and forced Chun to use alternative methods. But the tactic also revealed the infiltrator’s position and made them targets for grenades and conventional fire. By April 8th, the 150 M3 carbine operators in the 96th Infantry Division had been in continuous night combat for 7 days.

The cumulative impact was documented in the division’s afteraction report. During the period of April 1st through April 7th, the 96th Infantry Division recorded 412 confirmed Japanese casualties caused by rifle and carbine fire during night operations. Of those 412 casualties, 127 were attributed to M3 carbine operators. The M3 operators represented approximately 3% of the division’s infantry strength, but accounted for 31% of Japanese casualties from small arms fire during nighttime engagements.

The report noted that sectors covered by M3 operators experienced 94% fewer American casualties from infiltration attacks compared to sectors without M3 coverage. The weapon system was functioning as intended. It was providing American forces with the ability to see and engage the enemy in total darkness at effective combat ranges.

The Japanese could not counter it. They could not see the infrared light. They could not identify which American positions had M3 systems. They could not develop effective counter measures because they did not understand the technology they were facing. On April 12th, Japanese commanders issued new orders. An intelligence document captured later that month revealed the directive.

Night surface operations will be limited to final defensive positions only. Infiltration operations will be conducted only during periods of adverse weather or limited visibility. All units will prioritize defensive positions in caves and underground complexes where enemy observation is impossible.

The directive effectively ended large-scale Japanese night infiltration tactics on Okinawa. The American night vision capability had forced a doctrinal change. Japanese forces retreated into the extensive cave systems throughout the island. They fought from concealed positions during daylight hours. They abandoned the night attacks that had been effective at Guadal Canal, Saipan, and Iwima.

The M3 Carbine and its 150 operators had changed the tactical equation. They had made nighttime movement lethal for the enemy. They had protected the American perimeter during the most vulnerable hours. They had saved an estimated 200 to 300 American lives during the first week of the Okinawa campaign by preventing infiltrators from reaching defensive positions.

Chun continued operations through May. The M3 system was used less frequently as Japanese night operations decreased, but it remained effective when infiltrators did attempt movement after dark. On May 23rd, Chun was operating near Shuri Castle when he detected three infiltrators attempting to approach an American command post at 0312 hours. He engaged at 69 yards, three shots, three kills.

It was his last confirmed engagement with the M3 carbine. The battle for Okinawa ended on June 22nd, 1945. The 96th Infantry Division suffered 6,548 casualties during the 82day campaign. The division’s afteraction report credited the M3 carbine program with significantly reducing casualties during night operations and forcing Japanese tactical adjustments that limited their offensive options.

The M3 carbine program expanded after Okinawa. The US Army had planned to manufacture 20,000 complete systems for use in the planned invasion of mainland Japan. The systems would be distributed to all infantry divisions. Training programs were established at bases in the Philippines and Okinawa. But on August 15th, 1945, Japan surrendered. The invasion was cancelled.

The 20,000 M3 carbines were never produced. The technology developed for the M3 became the foundation for future night vision systems. During the Korean War, the Army deployed the M3 carbine successor, the M3A1, with improved range and reliability. During Vietnam, the A/PVS2 Starlite scope used passive infrared technology derived from the M3’s active infrared system.

Modern night vision devices used by American forces in Iraq and Afghanistan trace their lineage directly to the experimental system that private first class Robert Chun operated in April 1945 on Okinawa. Chun’s fate after Okinawa is not documented in available military records.

His name appears in no official commendations, no medal citations, no postwar interviews. He was one of 150 men who operated a classified weapons system during the final months of World War II. The technology was so secret that operators were forbidden from discussing it with other soldiers. After the war, most M3 carbines were destroyed.

The army cut them apart with torches to prevent the technology from being captured or studied by potential adversaries. Very few original M3 carbines survived. The ones that did are held in military museums, often with incomplete documentation about the men who used them in combat. Chun appears in modern historical analyses as a single name, a private first class in the 96th Infantry Division who demonstrated the M3 systems effectiveness during the first week of Okinawa.

His background before the war is unknown. His service after Okinawa is unknown. Whether he survived the war, where he lived afterward, when he died, all unknown. He exists in the historical record as a name attached to a weapon system. A soldier who saw in the darkness when others could not, who killed enemy infiltrators at 70 yards in complete blackness.

Who helped change the way modern armies fight at night. The men who operated the M3 carbine on Okinawa were not heroes in the traditional sense. They did not charge machine gun nests. They did not capture strategic objectives. They did not win medals for valor.

They sat in foxholes during the darkest hours, watching green shapes move through the night, squeezing triggers when the shapes came too close. They changed batteries when the power ran low. They cleaned condensation from scopes. They reported contacts and coordinates to command posts. They prevented infiltrators from reaching American positions. They saved lives by taking lives at distances where the enemy believed they were invisible.

The work was technical, methodical, unglamorous. It was also brutally effective. In 7 days, 150 men with experimental weapons killed 127 enemy soldiers, forced a doctrinal change in Japanese night tactics, and demonstrated that technology could overcome the oldest tactical advantage in warfare, darkness.

The M3 carbine is remembered today primarily by military historians and firearms collectors. The systems impact on nightfighting doctrine is studied at militarymies. The technologies evolution into modern night vision systems is documented in technical papers.

But the individual operators, men like Robert Chun, remain largely anonymous. They operated a weapon system so secret they could not discuss it. They achieved results so significant they changed enemy tactics. They saved lives that were never counted because those lives were defined by attacks that never happened. Infiltrations that never reached American lines, casualties that never occurred.

Chun and the other M3 operators on Okinawa fought a war the enemy could not see. They won it in the darkness, one green shape at a time, 70 yards away, with a car battery on their backs and a scope that turned night into day. The Japanese called it impossible. The American command called it experimental.

The 150 men who carried those 28-lb carbines through the tropical nights of Okinawa called it survival. If you believe men like Robert Chun deserve more than silence, leave a comment. Tell us where you’re watching from. United States, Canada, UK, Australia, anywhere. Our community spans the globe and you’re part of keeping these forgotten stories alive.

Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re bringing these histories back from the archives every single day. Real people, real courage, real impact. Thank you for making sure soldiers like Chun aren’t lost to

News

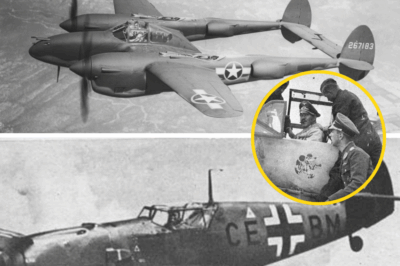

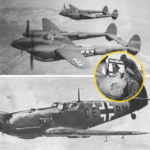

CH2 German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s The sky over Tunisia was pale…

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled The morning fog hung…

CH2 When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless At 9:27 a.m. on December…

CH2 Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day May 18th, 1944,…

End of content

No more pages to load