Germans Were Shocked When the M26 Pershing’s 90mm Gun Crushed Their Panthers – How America’s M26 Pershing Turned the Tide of Steel in Europe

The wind cut like a blade across the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, carrying with it the smell of cold oil, scorched cordite, and ambition. Rows of half-assembled tanks stood like sleeping beasts under a thin coat of frost, their steel hides painted in the flat olive drab of a nation still learning the science of war. Beneath the echoing rafters of Building 311, the clang of hammers and the bark of foremen mingled with the steady hiss of acetylene torches. America was building machines meant to crush fascism, yet on this December morning in 1944, even the most confident engineers sensed that they were racing against both time and physics.

At the far end of the bay, Colonel Gladeon M. Barnes, head of the Ordnance Department’s Research Division, stood before a wall-sized schematic of a German Panzerkampfwagen V Panther. Its lines were clean and cruel, its armor plates drawn at the impossible angles that had turned it into legend on the battlefields of France. Barnes’s gloved finger traced the front glacis plate—three inches thick, sloped at fifty-five degrees. “Eighty millimeters of hardened steel,” he said quietly. “Our seventy-five can’t even scratch it at a thousand yards.”

A young engineer beside him shifted uneasily. “Sir, we’re already running at maximum pressure. The M3 gun—”

Barnes cut him off. “The M3 is obsolete. The Germans are killing Shermans at fifteen hundred yards. We need something that kills them at two thousand.” His tone carried no anger, only the weary gravity of a man who had seen too many reports marked catastrophic loss.

Pinned to the corkboard behind him was one such report, sent from the 2nd Armored Division after the fighting around Saint-Lô:

Enemy Panthers open fire at ranges exceeding 1,500 yards. Shermans cannot reply effectively beyond 800. Penetrations frequent, even frontal. Recommend immediate improvement of main armament.

Someone had scrawled in pencil across the margin: We’re outclassed.

It was not the kind of note that belonged to the army of an industrial superpower, but there it was—three words of quiet desperation staring out from beneath the neat rows of typed numbers. Barnes stared at it for a long moment before turning back to the Panther’s drawing. “Gentlemen,” he said, “our boys are dying with courage. But courage is not armor.”

He walked toward the far end of the shed where a new prototype sat beneath a tarp. Its silhouette was heavier than the familiar M4 Sherman—lower, broader, its turret longer and thicker. A faint chalk mark on its side read T26E3. The tank had been born from a long lineage of failed experiments—the T20, T23, T25—each one a step closer to an answer the army refused to ask.

When the tarp came off, the fluorescent lights revealed a barrel unlike anything the Americans had fielded before: the 90-millimeter M3 gun, adapted from the anti-aircraft batteries that had once raked German bombers from the sky. Barnes placed his hand on the breech, feeling the cold steel. “This,” he said, “will put us back in the game.”

But even as the colonel spoke, he knew the battle ahead would not be fought in steel but in politics. General Lesley J. McNair, commander of Army Ground Forces, had built his entire doctrine on mobility and numbers. Tanks were not to duel other tanks; they were to support infantry, exploit breakthroughs, and rely on airpower for heavy killing. Heavy armor, McNair had insisted, was wasteful. “Quantity is quality,” he liked to say. “We can build fifty Shermans for every Tiger.”

In the cool reasoning of logistics, he was right. But in the hedgerows of Normandy, where Panthers stalked through fog and wheat, his logic burned with every tank that failed to return.

Inside Building 311, the engineers gathered around a cutaway section of Panther armor that had been shipped from the front lines. It was pocked with craters from 75-millimeter test rounds. None had gone through. “The angle’s the secret,” one metallurgist murmured. “Ricochet physics. It’s not just thickness—it’s geometry.”

“Geometry doesn’t matter,” Barnes replied. “Not when you hit it hard enough.”

He gave a signal, and the test crew wheeled the new M3 cannon into position on its stand. A target plate—five inches of German steel salvaged from a wrecked Panther—was set at fifty-five degrees on the firing range outside. Snow hissed softly underfoot as the men took cover behind sandbags.

“Range: twelve hundred yards,” the gunner called.

Barnes raised a gloved hand. “Fire.”

The blast shook the air. The 90-millimeter shell tore from the muzzle at nearly 3,000 feet per second, a streak of light and fury that struck the plate dead center. When the smoke cleared, there was a hole the size of a man’s fist where the steel had been.

No one spoke for a full ten seconds. Then Barnes exhaled. “Gentlemen,” he said, “we can kill it.”

The men stared through the drifting smoke, their breath frosting in the cold. For a moment, even the clatter of the factory seemed to pause. They had just watched the balance of the armored war shift before their eyes.

But triumph turned quickly to frustration. The War Department still hesitated. Moving a forty-six-ton tank across the Atlantic would strain every bridge, barge, and railcar in Europe. Supply officers complained about shipping tonnage; strategists warned of fuel shortages. McNair’s philosophy still haunted Washington like a ghost. “The Sherman wins wars of movement,” his disciples said. “Heavy tanks slow the advance.”

Barnes knew better. “Tell that to the men burning inside their Shermans,” he snapped during one meeting at the Pentagon. “They’re not losing mobility—they’re losing lives.”

By autumn 1944, those lives numbered in the thousands. Reports from the Third Armored Division were grim. Tank crews nicknamed the Panther the Murder Cat. “We can’t flank fast enough,” one captain radioed after a failed assault near Mons. “We lose five for every one we kill.”

At Aberdeen, the engineers worked without rest. They ate in the testing sheds, slept beside blueprints, and drank black coffee that tasted of gun oil. Each new revision of the T26 brought them closer to perfection: thicker armor, improved torsion bars, hydraulic traverse, a lower profile. It was a tank designed not for doctrine but for survival.

In late November, Colonel Barnes sent a cable to Washington marked URGENT PRIORITY:

Combat experience demonstrates immediate need for tanks superior in firepower and protection. Current models inadequate. Recommend mass production of T26E3 without delay.

It was his last appeal. On Christmas Eve, the reply came back, signed by General Jacob Devers of the European Theater of Operations:

Approved. Initiate limited combat deployment—Operation Zebra.

Twenty prototypes would be shipped to Europe for field testing. Twenty machines to prove, or disprove, the dream of parity.

The men at Aberdeen celebrated with black coffee and exhaustion. Outside, the snow kept falling, covering the tracks of tanks that had yet to see battle. Somewhere in France, American soldiers were fighting in the frozen forests of the Ardennes, surrounded at Bastogne, their Shermans outgunned once again by Panthers and Tigers. For them, help was still an ocean away.

In Detroit, the Chrysler Tank Arsenal came alive under floodlights that turned the smoke into a glowing haze. Welders worked through the nights, sparks cascading over the steel hulls lined up like giants waiting for war. A young welder scrawled on the inside of a turret in chalk before it was sealed shut: Send this one to Germany—we owe them a visit.

The first Pershings—named after General John J. Pershing of the Great War—rolled off the line in January 1945. Their armor was three inches thick at the front, their engines the same Ford GAF V-8 used in the Sherman but forced to carry ten more tons of steel. They were not perfect, but they were powerful, and for the first time, American crews could look at a Panther and not feel helpless.

At the port of Newport News, cranes strained to lift the massive tanks onto Liberty ships bound for Antwerp. Each hull swung over the water like a promise forged in iron. As the last ship cleared the Chesapeake and turned east into the Atlantic swell, Barnes watched from the pier, his collar turned up against the wind.

He said nothing. There was nothing left to say.

The tanks were gone, and their fate would be decided not by blueprints or memos, but by men who would drive them into the fire.

Thousands of miles away, under the gray skies of western Germany, those men were already fighting for every mile. In a small village outside Cologne, Sergeant Clarence Smoyer of the 3rd Armored Division climbed out of his Sherman and stared at the horizon, where columns of smoke marked the path of retreating German armor. The ground trembled under distant cannon fire.

“Panthers again,” his gunner muttered.

Smoyer lit a cigarette with shaking hands. “Maybe next time we bring something bigger.”

He didn’t yet know that it was already on its way across the ocean—that somewhere, inside a steel hull marked Fireball, the answer to his prayer was coming.

And when it arrived, it would change everything.

Continue below

At the US Army Ordinance Proving Grounds in Aberdeen, Maryland, the winter wind cut across rows of half assembled tanks, hulking shapes of olive drab steel, and raw ambition. Beneath the echoing rafters of building 311, engineers in coveralls argued in the language of armor thickness and muzzle velocity, their voices rising above the clatter of rivets and the groan of hydraulic presses.

What began as routine testing of the M4 Sherman had become something else entirely, an awakening. By early 1944, the American tank program was under quiet siege, not from enemy guns, but from battlefield reports trickling back from Europe and Italy. The Sherman, that dependable, mass-roduced workhorse that had carried American divisions across North Africa and Sicily, was being mauled in Normandy.

The Panther, the German Panzer Campfen 5, was cutting through US armor columns like a sythe through wheat. A memo from the second armored division dated July 1944 was pinned to a corkboard in the ordinance analysis section. Enemy tanks open fire at ranges exceeding 1,500 yd. Shermans cannot reply effectively beyond 800. Penetrations are frequent, even on the frontal glacis.

Another note scrolled in pencil across the margin read simply, “We’re outclassed.” At Aberdeen, Colonel Joseph Kby, head of the tank automotive branch, traced his finger across a cross-section drawing of a Panther’s gun. 75 mm, he said almost in disbelief. High velocity KWK42 L70. Their shell leaves the barrel at over 3,000 ft pers. He looked up at his engineers.

Gentlemen, our 75 mm M3 is an antique. The men in that room were not blind to logistics. They knew the Sherman was not built to win jewels. It was designed to win a war of movement. America could produce 50 Shermans for every Panther. Spare parts, transportability, fuel.

Those were the pillars of McNair’s doctrine. General Leslie J. McNair, head of army ground forces, had long resisted the notion of heavy tanks. He called them wasteful and unnecessary. His belief was doctrinal, even moral. The United States would win with mobility numbers and the airarm, not lumbering behemoths that clogged ports and bridges.

Yet in France, that doctrine was burning. A captured German intelligence briefing translated and circulated by G2 in August 1944 revealed how the enemy saw it. American armor is tactically inferior. Sherman is fast, yes, but under gunned. Panther engages freely at long range. One Panther may engage four or five Shermans before withdrawal. At Ordinance Headquarters, that statement felt like a gauntlet thrown.

The first glimmer of a countermeasure had begun a year earlier in the experimental bays at Detroit Tank Arsenal. There, engineers had quietly tested prototypes designated T20, T23, and T25, evolutionary designs that abandoned the Sherman’s narrow chassis and vertical volu suspension for torsion bars, wider tracks, and heavier guns.

The T-23 carried a new 76 mm cannon, while the T-25 mounted a 90 mm, an adaptation of the Army’s anti-aircraft weapon, the M1. On paper, it could pierce a Panther’s armor at 1,200 yd. But McNair’s voice haunted every conference table. Heavy tanks will slow operations, he insisted. We need reliable tanks in quantity, not super weapons. In Washington, his doctrine carried weight. In Europe, his words were costing lives.

In July 1944, an engineer named Robert Kelner returned from France with firstirhand accounts from the Third Armored Division. His debriefing was grim. Our tankers call the Panther the Murdercat. They can’t flank fast enough. Our 70s bounce off its front plate. We get close, but at the cost of five tanks for one. The room went silent.

Kelner laid a spent shell casing on the table, a 75 mm AP round recovered from a Sherman’s gun. The nose was flattened like a coin. This struck a panther at 900 yards, he said. It left a mark, nothing more. Behind him, a photograph projected onto the wall. A burntout Sherman on a Norman road, its turret blown a skew, white stars charred black.

Our boys aren’t lacking courage, Kelner said. They’re lacking physics. The phrase circulated through the corridors of ordinance, lacking physics. Meanwhile, intelligence officers began dissecting captured German equipment at Aberdeen’s ballistics range. A Panthers glacis plate, angled at 55° and 80 mm thick, deflected everything the Americans threw at it.

The KWK42’s tungsten core shells, on the other hand, punched through US armor cleanly. The contrast was humiliating. In September 1944, Ordinance Chief General Gladian Barnes visited the range personally. He watched as a prototype 90 mm M3 cannon roared, sending a shell through a steel block designed to mimic a Panther’s side armor. The block shattered. There, Barnes said.

That’s our answer. Still, the army’s bureaucracy lagged. Convincing McNair’s successors to approve large-scale production was a political battle as much as an engineering one. The tankers in Europe were pleading for relief. While the shipping officers in New York warned that the new design, heavier by 10 tons, would strain transport logistics.

The T-26 project, as it was now designated, faced resistance from every quarter except the front lines. Eisenhower’s staff cabled the war department directly. Combat experience clearly demonstrates the need for tanks superior in firepower and protection. Our current models are no longer adequate.

In October 1944, the 12th Army Group sent a detailed afteraction report to Washington. Its summary line was damning. The German Panther outclasses the Sherman in all aspects except reliability. For the first time, even the Ordinance bureaucrats could not ignore the arithmetic of destruction. In the hedge of Normandy, in the streets of Slow and KH, American tank crews learned that courage and maneuver meant little against a gun that could reach them from a mile away.

By winter, production orders for the T-26E3 were finally approved, an emergency program that would later yield the M26 Persing. Only 20 were initially allocated for combat testing in Europe under what became known as the Zebra mission. But in the closing months of 1944, that was still a dream. The men in the Aberdeen testing sheds worked double shifts, sleepdeprived and determined, measuring armor plates by flashlight, running weld seams with frost on their breath.

In their minds, every hour saved meant fewer Shermans burning on European soil. Late one December night, a test firing rattled the proving ground. The new 90 mm thundered and the recoil shuddered through the floor. The shell struck its target. 5 in of German steel salvaged from a wrecked panther and punched clean through. Silence followed.

Then one engineer, his voice half disbelief, half triumph, said softly. Gentlemen, we can kill it. But as 1944 turned into 1945, that victory remained theoretical. The reports from the Western Front were still grim. At Bastonia during the Arden counter offensive, American tank units faced panthers and tigers in the snow and fog, and still the 75 mm guns failed to penetrate. “We hit them five times before they hit us once,” a tanker wrote home.

“The difference is one of theirs is enough. The gap was not of courage or industry. It was of steel and time.” In the long corridors of Aberdeen, the engineers now spoke in hushed tones. They knew what they had built, but they also knew it would come too late for many. The Persing’s birth would be measured not only in tons and millimeters, but in blood already spilled on the fields of France.

And so, in the anxious winter of 1944, as draftsmen inked the final blueprints of the T-26, one thought echoed in every hanger and foundry. America would no longer send its tankers to fight with physics against them. The era of the Sherman was ending. The age of the Persing was about to begin. Eastern France, summer autumn 1944. The morning haze of August 1944 clung to the rolling fields outside Chartra, veiling the black silhouettes of the German armor that crouched among the hedge.

Panthers, sleek, angular, menacing, their long 75 mm guns pointed west across a landscape already rumbling with the approach of American columns. From his cupup, Oberfeld Wable Carl Hoffman of the second Panza division adjusted his Zeiss binoculars. “Shermans,” he murmured, spotting the specks of movement 2 km away.

“Always Shermans!” The panther had become a creature of both engineering and mythology. Among German tankers, it was a symbol of survival, a predator that even in defeat commanded fear. In training manuals and messaul boasts, they called it Duova Europas, the lion of Europe. With its 75 mm KWK42 gun and 80 mm sloped frontal armor, the Panther was said to be impervious to any Allied tank fire except at suicidal range.

That belief was both weapon and curse. When Hitler had unleashed the Panther in 1943 at Kursk, it had faltered, mechanically fragile, plagued by engine fires and transmission failures. But by the time it rolled into France in 1944, those flaws had been mostly corrected.

The crews who manned them were veterans hardened by the Eastern Front, where duels at 2,000 m against T34s were commonplace. Against the Americans, they expected a massacre, and often they got one. At the edge of a Norman village, a panther from the 116th Panza Division waited hull down behind a rise. Its commander, Leitant Eric Brandt, watched an advancing US column through the smoke of burning farmhouses. Range 1,400 m, his gunner called.

Target lead tank. The retort was like thunder in a cathedral. The 75 mm round shrieked through the air, a tungsten core arrow that struck the Sherman square in the glacis plate. In an instant, fire erupted through the turret seams. The crew inside had no chance. The next Sherman edged forward, firing wildly. Another shot from the Panther. Another bloom of orange and black.

In less than 3 minutes, four Shermans burned. The German crews laughed grimly, their confidence renewed with every hit. The aim is build tanks like sausages, one Panther driver sneered, watching the horizon. And we roast them just as fast. But behind that arrogance lay exhaustion and fear.

The radio crackled constantly with desperate calls for fuel, for air cover, for ammunition that no longer arrived. Each victory felt hollow when followed by the hiss of siphoned gasoline and the grinding march on foot. By late August, the Panza lair division, once the pride of the Vermacht, had been reduced to half strength.

Its panthers, still lethal, now operated as isolated wolves, striking swiftly before vanishing. The German supply lines had been shredded by Allied fighter bombers. For every panther that destroyed a Sherman, another sat immobilized for want of spare parts or fuel. Still, to the Americans facing them, the Panther seemed invincible.

Reports from the Third Armored Division described engagements in which entire platoon of Shermans were lost before closing to effective range. “Our guns can’t touch their fronts,” one lieutenant wrote bitterly in his combat diary. “The only way to kill a Panther is to flank it. And to do that, you have to lose half your tanks getting there.” At headquarters, American commanders adjusted tactics in desperation.

Air support was called in wherever Panthers appeared. Tank destroyer units M10s and M36 with 90 mm guns were rushed to the front. Infantry learned to stalk the beasts with bazookas, grenades, and even satchel charges. A panther’s rear is its weakness. Instructors said the problem was living long enough to reach it.

For the Germans, the Panthers dominance brought not relief, but a grim fatalism. They knew the Allies had endless reserves of tanks, men, and gasoline. Each skirmish they won was another hour’s delay in an inevitable retreat. “We kill 5, 10, 20 Shermans,” Hoffman wrote in his journal. “But for everyone we burn, two more appear behind it. They come like a tide, never ending.” The myth of superiority became a psychological trap.

Crews grew contemptuous of orders to withdraw, believing that no Allied tank could best them in a stand-up fight. But when the skies darkened with P47 Thunderbolts, confidence turned to terror. Armor meant nothing when a 500 lb bomb struck the earth beside you. At the Lir River, a Panther company from the 9th Panza Division attempted to hold a bridge head.

Their commander, Halpedman Victor Laauo, remembered the sound first, a distant droning that rose into a scream. “Jabos!” someone shouted. The thunderbolts came out of the clouds, strafing with 050 calibers, then dropping rockets that tore through the German column. Panthers burned on the bridge, their crews clawing out of hatches into flames.

When the smoke cleared, three panthers remained from 12. The road to Paris was open. Even in ruin, the Panthers aura persisted. Captured American tankers spoke of facing them with a mixture of dread and respect. “If you saw that long gun in the treeine, you knew someone was about to die,” recalled Sergeant William Lucas of the 33rd Armored Regiment.

“The only good thing about a Panther was that if you survived the first two minutes, it might break down trying to chase you.” Mechanical failures became the Germans silent enemy. Overstrained engines, transmission failures, cracked torsion bars. The Panther was a masterpiece built for a nation that could no longer afford it.

As the Vermach retreated eastward, mechanics stripped abandoned Panthers for parts, often torching what they couldn’t move to deny them to the Allies. In October 1944, a captured Panther was shipped to the Abedene proving ground. Engineers swarmed over it like archaeologists examining the relic of a vanished empire. They measured, weighed, and tested every plate, every weld.

It’s an engineering marvel, one of them admitted. But it’s over complicated. You can tell they’re fighting desperation with precision. To the German tank crews, the Panther remained their last faith. When they met in the muddy bivwax along the Moselle, they spoke not of victory, but of endurance.

“We hold them today,” one sergeant said, “because our gun reaches farther than theirs.” “Tomorrow, who knows? Tomorrow came sooner than they expected.” “In the factories of Detroit and the testing grounds of Aberdeen, the answer to the Panther was already being forged. the T26E3, a tank with a gun that could match the German weapon and armor that could shrug off its fire.

The German crews didn’t know it yet, but the age of their supremacy was measured in weeks. As autumn turned to winter, the Panther remained the king of the battlefield, but its kingdom was collapsing around it. Fuel convoys vanished under Allied air attack. Spare parts ceased to arrive. orders came from higher command that sounded more like prayers than strategy. Hold, delay, resist.

And so on the frostbitten fields of Lraine, as columns of smoke marked another day’s retreat, the men of Panza Lair and Second Panza still believed that their steel lions could turn the tide. They did not yet know that across the channel in the holds of liberty ships bound for Antworp, a new beast was on its way.

A tank born from their own legend, designed for one purpose, to hunt the Panther. Detroit Tank Arsenal and Aberdeen Proving Ground, late 1944. By the autumn of 1944, in the machine shops of the Detroit Tank Arsenal, the air smelled of steel, cutting oil, and exhaustion. Engineers worked under flood lights that turned the foundry’s haze into something almost sacred.

Here, amid the roar of presses and the hiss of welders, the Americans were trying to erase their greatest military embarrassment, that their army had gone to war with tanks that could not stand toe-to-toe with Germany’s best. The Panther had been dissected, measured, and cursed.

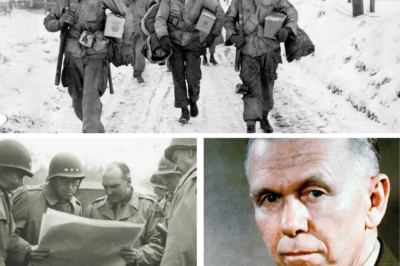

Aberdeen’s ballistic engineers had pried apart its suspension, weighed its armor, and cataloged its weapon like priests examining a pagan idol. Their conclusion was simple, humiliating, and undeniable. The Sherman’s 75 mm gun could not penetrate the Panthers frontal armor at any reasonable combat range. Colonel Gladon M.

Barnes, chief of the ordinance department’s research division, made his judgment in a tur memo to Washington. We require a tank capable of meeting the Panther on equal terms, firepower, armor, and optics, nothing less. His weapon would be the T-26E3, a machine conceived in frustration and born of engineering defiance. It would mount the 90 mm M3 gun, the same piece of ordinance that had already proved capable of downing German aircraft at 10,000 ft and punching through a Tiger’s side armor at 1,000 yards.

But building a new tank was one thing. Getting it to the battlefield was another. Standing in the way was General Lesie McNair’s legacy, still embedded in Army ground forces doctrine. Even after McNair’s death in Normandy that July, his philosophy haunted every production meeting. Mobility over weight, reliability over complexity.

Heavy tanks, the staff officers said, would bog down in French mud, overload shipping, and burn too much fuel. The Sherman, they argued, had won North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. Why replace what worked? But Barnes had seen the casualty reports at St. Low and Mortain Sherman crews had died in droves trying to outflank panthers that could pick them off from a mile away. Every success had been purchased in blood.

Our boys are brave, Barnes told his engineers. But courage isn’t armor. So in defiance of inertia, he ordered prototypes built. The T20 series came first. Low silhouettes, electric turrets, and improved suspensions. Promising but undergunded. The T-23 mounted a 76 mm cannon and an electric transmission that fascinated engineers but terrified logisticians. Too complicated.

The T-25 brought a 90 mm gun, heavier armor, and a 45 ton chassis. And with it the beginning of the T-26 line at Aberdeen, a prototype was test fired in October 1944. The 90 mm M3 spat a shell that tore through a captured panther’s glacis plate at 1,200 yd. The steel rang like a church bell, and the observers went silent. There, Barnes said quietly.

That’s the sound of par. But even with the proof in front of them, bureaucracy slowed everything. To ship a 46-tonon tank to Europe meant redesigning bridges, barges, and transport cars. The War Department hesitated. Eisenhower, thousands of miles away in France, did not. His cable to Washington was blunt. The need for heavy tanks here is urgent.

I request immediate delivery of 90 mm gun tanks to ETO. That order birthed Operation Zebra, the code name for the shipment of 20 T26E3 tanks to Europe for combat trials. The crews selected for the mission were from the 3rd and 9inth armored divisions, veterans of Normandy and the Sief freed line. They arrived at Aberdeen to train under conditions more suited to laboratory tests than battlefield chaos.

Engineers hovered around them, clipboards in hand, as if the men were test pilots for a secret weapon. Staff Sergeant Robert Early, one of the chosen tank commanders, remembered seeing the Persing for the first time. It looked like a Sherman that had gone to the gym, he said. Same outline, but lower, broader, meaner.

When you swung that 90 around, you knew it meant business. The crews were taught the new hydraulic traverse, the improved periscopic sights, the 3-in thick frontal armor plate. For the first time, an American tank could meet a Panther headon without flinching. You could feel the weight, Earlyie said later. Not just in the steel, in the confidence.

At the Chrysler Arsenal, production teams worked double shifts. They stripped down designs, simplified welds, and welded plates by hand where machines fell behind. Every tank had to be perfect. There was no time for repair units to learn on the fly. By December 1944, the first shipment of Persings was loaded onto Liberty ships bound for Antworp.

The cranes strained as the massive tanks were hoisted aboard, dwarfing the Shermans parked beside them. As the ships steamed across the Atlantic, the Battle of the Bulge erupted. Reports from the Ardens were catastrophic. Panthers and Tigers spearheading through snow and fog, Shermans burning in clusters, American tank units retreating under withering fire.

Eisenhower’s headquarters at Versailles sent another cable to ordinance. We need those new tanks now. The irony was cruel. The Persing had been ready for months, delayed by committees. Now, as Europe froze under Hitler’s last offensive, the machines that could have stopped it sat on the decks of ships somewhere in the North Atlantic. At Aberdeen, the test ranges stood empty.

The engineers who had stayed behind waited for word of how their creations would perform in real war. They passed the long nights in the drafty barracks, listening to the radio reports from Europe, Bastonia surrounded, pattern racing north, the lines holding by inches.

Barnes wrote in his journal that week, “It will not be the best tank that wins this war, but the one that arrives in time.” The Persing’s time had come, but whether it would arrive soon enough was uncertain. On the factory floor in Detroit, a young welder scrolled in chalk on the inside of a turret before it was sealed shut. Send this one to Germany.

We owe them a visit. When the cranes lifted the next Persing into the Atlantic dawn, its olive paint still tacky under the cold mist, no one in that shipyard could yet know that one of these tanks, number 38, would soon duel a panther in the ruins of Cologne Cathedral. And that when its 90 mm gun fired, it would change the balance of armored warfare forever.

Cologne, Germany, March 6th, 1945. The air over Cologne was thick with smoke and the echo of falling masonry. After months of brutal fighting across the sief freed line, the third armored division rolled into the city, its columns advancing like weary metal beasts through the shattered bones of the Reich.

Every street was a canyon of ruin, burned out trams, collapsed facads, and the smell of cordite lingering like an open wound. Among the column was one of the new M26 Persings, freshly unloaded from Antworp only weeks before. Its name, scrolled in white chalk on the gun barrel by its crew, was Fireball.

Commanded by Sergeant Clarence Smoyer, the Persing had been the object of curiosity and quiet hope since it arrived. To the Sherman veterans around it, the tank looked like something from the future, heavier, meaner, and blessed with the thick armor and long 90 mm gun that could finally challenge the feared panthers. That morning, as the armored column entered the city center, scouts reported a German tank hidden near the Cologne Cathedral, the twin spires looming above the wreckage like sentinels.

The Persing crew was ordered forward. Every block they advanced carried a sense of both dread and destiny. Somewhere ahead, an ambush waited. At the intersection of Komodian Strasa and Marzellan Strasa, they found it. A panther forms a camouflaged amid the debris, its 75 mm gun already traversing toward them. The crews saw each other almost simultaneously.

“Panther dead ahead!” shouted gunner John Derriggi, sighting through the periscope. Before Smooyer could give the order, the Panther fired. The shell struck the front plate of fireball, gouging the paint but failing to penetrate. Sparks flew and the tank rocked back on its suspension. Hit no hole. Load AP exclamation mark. Duriggy barked.

Loader Truman Evans rammed the heavy armor-piercing round into the brereech. The smell of grease and hot metal filling the turret. Duriggy adjusted, exhaled, and squeezed the trigger. The 90 mm gun thundered. The shell streaked across the street, hitting the Panther square in the side of its turret.

The German tank jerked, belched smoke, then caught fire. Flames poured from the commander’s hatch as its crew scrambled out. Too late. A second round from fireball tore through the engine compartment, sealing the kill. For the first time, an American tank had defeated a Panther in direct head-on combat. The moment was caught by a combat cameraman crouched behind rubble, a film clip that would become one of the most iconic pieces of footage of the war. Inside Fireball, the crew sat in stunned silence.

Then Smooyer broke the stillness. That’s for every Sherman that burned before us. Word spread quickly through the division. The Persing’s baptism had not only proven its worth, it had vindicated years of engineering, argument, and loss. The men of the Third Armored began to believe that the tide of steel had finally turned.

But victory came too late to change the war’s course. By the time more Persings arrived in Europe, the Reich was collapsing. The rurer pocket was forming, the rine crossings secured. Most Shermans that remained were now supported by air supremacy and artillery, the edge the Allies had always held.

Still among tankers, the Persing’s arrival carried symbolic weight. It was America’s longdelayed answer to the Panther and Tiger, the closing of the steel gap that had haunted them since Normandy. At the edge of Cologne, Smooyer’s crew parked Fireball and climbed out to watch the fires consuming the city. Church bells rang somewhere through the smoke, faint, defiant.

Around them, infantrymen moved like ghosts through the rubble. Rifles slung low. The Persing’s 90 mm barrel still smoked faintly. In its reflection, the men saw the end of one era and the beginning of another. the moment when the US army finally met its enemy on equal terms of iron and courage. By the end of March, only a few Persings had seen combat.

Yet, their brief presence had already reshaped doctrine. Engineers and officers back in Detroit and Aberdeen took note. The next war would not be fought by masked light tanks. It would be fought by giants. As Fireball stood amid the ruins, its armor blackened and its crew weary but alive, a single phrase seemed to echo in the minds of all who saw it.

Too late for this war, but just in time for the next. April, August 1945, Western Germany and the US Ordinance Board. The Persing’s triumph in Cologne spread across the Western Front like a whispered promise, proof that the Americans could finally stare down a panther or tiger without praying for a flanking shot or air cover.

Yet the timing was cruel. By the time the third and ninth armored divisions received their new tanks, the war in Europe was already gasping its last breath. Only 20 Persings saw frontline action before VE Day. They arrived peacemeal, trucked through muddy French depots, and rushed across the Rine on pontoon bridges under the roar of Allied aircraft.

Each one was greeted with a mix of reverence and resentment by Sherman crews who had survived months of attrition. “Where were these damn things in Normandy?” one sergeant muttered, touching the thick front glacis of a new M26 as if testing a myth.

In the chaos of Germany’s collapse, the Persings rarely faced their intended prey. The vaunted panthers and tigers were dying not in duels, but in ambushes, bombings, and fuel starvation. The Reich had run out of everything: oil, crews, and time. Still, in the few engagements that did occur, the Persing proved itself merciless. At Remagan, where the Ludenorf bridge gave the Allies their first crossing of the Rine, a handful of Persings guarded the bridge head against desperate German counterattacks. One knocked out two Panthers at 1,200 yds with three rounds, the third blowing

the turret clean off. After action reports from the 13th Corps praised the tank’s accuracy and crew survivability, “Enemy fire failed to penetrate frontally at normal ranges,” one officer wrote. “The 90 mm guns effectiveness exceeds expectations. Recommend continued production and deployment. But even as the tankers celebrated, the bureaucrats debated in Washington and Detroit. The ordinance department and the armored board at Fort Knox began to argue over the Persing’s future.

Critics pointed out its flaws. The same gasoline engine as the Sherman, overburdened by 10 extra tons of steel, mechanical teething issues, underwhelming speed on poor roads. The Persing was powerful, yes, but slow to build, slower to maintain, and already outdated by the standards of engineers looking ahead to jet age warfare.

General Jacob Deas, a longtime advocate for heavy tanks, defended it fiercely. We asked our boys to fight Tigers with Shermans. Never again, he wrote to the War Department. But General Leslie McNair’s legacy lingered even after his death in Normandy.

The doctrine he had championed, mobility over mass, numbers over armor, still shaped procurement policy. The Persing is a fine weapon, one ordinance colonel conceded. But the war has been won without it. The irony was bitter. The tank built to close the steel gap had arrived only in time to watch Germany burn.

Its debut had proven America could match German engineering, but not fast enough to matter strategically. When victory came in May, many Persings were parked in depots, their treads still caked with rin mud, their barrels clean and unused. Crews posed for photographs beside them, unaware that these machines would soon be shipped not home, but east to new battlefields under new flags. For the war in Europe had ended, but another horizon was forming. the Pacific.

Reports from Okinawa told of Japanese anti-tank ambushes and concrete fortifications that laughed off 75 mm shells. The ordinance board began drawing up new deployment lists. The M26, born from panic and perfected too late for Europe, was now being readied for the invasion of Japan.

Mechanics repainted their hulls, olive drab, and stencled fresh shipping codes. The tank that had finally silenced the Panther was about to face an entirely different kind of enemy. Not armor, but empire. And in that quiet between wars, one truth settled among the engineers and soldiers who had built and fought in steel. America had learned its lesson the hard way.

The age of the light tank was over. From now on, no army of democracy would ever go to war under gunned again. June August 1945, Okinawa, Tinian, and Ordinance Command, San Francisco to Manila. When the guns in Europe fell silent, the men of the Third and 9th Armored Divisions scarcely had time to rest before hearing the new orders.

Prepare for redeployment to the Pacific. The war with Japan still raged across the islands, and Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Kiushu and Honshu, demanded every available armored division. In the humid summer of 1945, the M26 Persing began a new journey. Created aboard Liberty ships and victory freighters.

The tanks left Antwerp and Southampton, crossed the Atlantic, and were offloaded at American West Coast ports, San Francisco, Seattle, and San Pedro. There they were reconditioned, fitted with deep wading gear, tropical filters, and the Pacific olive paint tone used by marine armor units. At the San Francisco Ordinance Depot, a young army engineer named Captain Walter Swanson wrote in his report, “We are shipping weapons made for Europe to fight a war of coral and caves.

Yet, the Persing is the first tank I’ve seen that might survive what’s waiting on Kyushu.” Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Battle of Okinawa was grinding toward its bloody conclusion. The army’s 713th tank battalion, equipped with Shermans and flame tanks, fought yard by yard against Japanese bunkers and reverse slope guns.

Tankers there had learned to fear the hidden 47 mm anti-tank guns that ambushed from caves and the suicide teams that ran beneath tanks with explosives strapped to their chests. When news reached them that heavier tanks were coming with twice the armor and a gun that could shatter concrete, morale lifted, if only slightly. Maybe this one will live long enough to see the beach, one gunner wrote home.

By July, the first M26s had arrived on Tinian and Lee for evaluation. Crews trained under the blazing sun, learning to handle the 45ton monsters in tropical terrain. Engineers built experimental track extensions for mud and coral. Ordinance officers tested the 90 mm shells against reinforced Japanese bunkers, noting with grim satisfaction that one shot could breach what had taken Sherman’s three or four.

But the Pacific was a different kind of battlefield, not one of armored jewels, but of fortresses and cliffs, of jungles that swallowed engines whole. The Persing’s size and weight became both blessing and curse. It could withstand almost anything the Japanese fired at it.

Yet moving it through narrow trails, swamps, and shallow harbors was an ordeal. Still, the logic was simple. If America invaded Japan, it would need Persings at the front. The planners of Operation Olympic estimated over 1,000 would be required in the first wave alone. Production lines at Detroit Arsenal rumbled back to life, and new orders were issued to ship entire battalions of M26s by August. The crews who trained on them knew the stakes.

Sergeant Bill Ree of the 9th Armored Division wrote in his diary on July 31st, 1945. They say the Japanese are building concrete tank traps all around Kyushu. The brass think the Persing can take it. After what I saw in Germany, I believe them, but I’m not sure I want to find out. Then suddenly, the war changed overnight. On August 6th, the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

3 days later, Nagasaki followed, and on August 15th, Emperor Hirohito’s voice crackled over Japanese radios, announcing surrender. For the Persings waiting on the docks, it was a reprieve from a future written in blood. The invasion that would have cost hundreds of thousands of American lives never came.

The tanks that had been destined for Kyushu remained in their crates, silent, untested in the Pacific Crucible. Yet their voyage had not been in vain. As the occupation of Japan began, a handful of Persings were shipped to Tokyo and Yokohama to serve as security and demonstration units. They stood in stark contrast to the burnedout wrecks of Japanese HGO and Chiha tanks, relics of another era. Japanese officers, now prisoners, studied the Persings with quiet astonishment.

One former colonel from the Imperial Fourth Tank Regiment remarked during interrogation. We believed the Americans had no heavy tanks. This one is beyond anything we imagined. In the final weeks of 1945, as peace settled over a shattered world, the Persing stood as a symbol of lessons learned too late.

It had been conceived in panic, perfected in haste, and sent to war in its final chapter. A weapon born from defeat, but destined for a new age. For even as the last Liberty ships returned home, ordinance planners were already drafting the next generation, the M46 pattern, an improved Persing with a new engine and the promise of greater speed. The shadow of the Cold War was already falling.

The Persing had crossed an ocean only to find its war already won, but it carried within its steel frame the legacy of every Sherman that burned, and every engineer who swore it would never happen again. As one ordinance officer wrote at war’s end, “The M26 Persing arrived too late for glory, but just in time to remind the world that America could build not only many tanks, but great ones.

The war had ended, but the arguments had not. In the ruins of Germany and the laboratories of America, the story of the M26 Persing was being rewritten, not by its crews, but by generals, engineers, and historians trying to explain what it meant. At Fort Knox, the US Armored Board convened its postwar review in early 1946.

Around a long oak table sat men who had fought through Normandy, the Ardens, and the Rine. Some wore ribbons heavy with campaign stars, others slide rules in their breast pockets. The question before them was simple and damning. Had the US Army failed its tankers? Brigadier General Bruce Clark, veteran of the Seventh Armored, didn’t mince words, “We built a tank for 1942 and kept fighting with it in 1944.

” He said the Persing came too late to save men who died in Shermans that never had a chance. Across the table, an ordinance officer from Detroit countered. We built what our logistics could support. The Sherman won the war because it moved. Heavy tanks win battles, but light tanks win campaigns.

The debate echoed the old war between mobility and firepower, a philosophical fault line that had haunted the US Army since North Africa. The Persing had proven that American industry could produce a worldclass heavy tank, but at a cost. It was harder to transport, slower to repair, and logistically hungry. To the men who had to ship millions of gallons of fuel and parts across oceans, the Sherman had been a logistical miracle.

Yet for those who had fought in one, the Persing represented something deeper, a moral correction. The film of the Cologne duel shown during the board’s closed session made the point wordlessly. The flickering image of a Panther exploding under a Persing’s 90mm gun silenced the room. Colonel John Leonard, who commanded the 9inth Armored Division at Rayan, leaned forward.

Gentlemen, we can’t ask our men to fight steel with tin again. Not ever. Outside the hearing rooms, the engineers at Detroit Arsenal were already working to answer that demand. They stripped down a Persing and began re-engineering it, replacing the underpowered Ford GAF engine with a Continental AV1790, reinforcing the suspension, improving the transmission.

The result tested in 1947 was the M46 pattern, the Persing’s faster, leaner descendant. But as the blueprints advanced, the political winds shifted. America’s wartime arsenal was shutting down. Congress slashed defense budgets. Factories that once turned out Shermans and Persings now made refrigerators and cars.

To the public, the arsenal of democracy had done its job. Few wanted to fund the next war. Only a handful of men, ordinance officers, tacticians, and veterans saw what was coming. In 1947, as tensions with the Soviet Union hardened into the Cold War, intelligence reports described new Soviet tanks being tested. The T44 and T-54, both faster, lower, and armed with 100 mm guns.

For the first time, American strategists realized they were once again on the verge of falling behind. The lesson of Cologne, the price of complacency, was being learned all over again. Meanwhile, in occupied Germany, the Persings that had survived the final months of combat were being used for trials and demonstrations. American officers tested captured Panthers and Tigers side by side with the M26, recording data.

Meticulously, the results confirmed what tankers already knew. In firepower and armor, the Persing was a near match for the Panther and superior in reliability. Against the Tiger, it held its own, and against anything lighter, it was untouchable. One Panther, recovered near the Herkan Forest, was restored to working order for comparison firing.

When the Persing’s 90mm HVAP round penetrated its glasses at 1,000 yards, the German observers, former tank officers now working for US analysts, nodded silently. So, one murmured in English, “You learned from us after all.” By 1948, the Persing had become both a relic and a foundation.

Most of its production models were reassigned to training units or scrapped for parts, their components feeding the birth of the patent series. Yet, its reputation grew in retrospect, a tank that symbolized the end of one war and the beginning of another. In technical manuals, the M26 was classified as a medium tank, but to the men who drove it, it would always be the heavy that came too late.

And yet without it, America might never have built the tanks that would later face the T-34s in Korea, the T-55s in Vietnam, or the T72s of later decades. When the Armored Board issued its final report in November 1948, one line stood out. The M26 Persing corrected at last the doctrinal errors that cost us so dearly in Normandy.

Its existence ensures those errors need not be repeated. The report was stamped classified, restricted distribution, and filed away at Fort Knox. Outside, on a quiet Kentucky field, a single Persing sat rusting beneath a tarp. A test driver had scrolled a message on its turret in chalk before it was mothballled. Cologne, March 45, never forget.

And for the next generation of tankers who would climb into the Pattons and later the Abrams, they never did. By the time the 1940s faded into the 1950s, the M26 Persing had already become a paradox, a weapon both too late and too early. Too late for Europe’s great tank jewels, too early for the jet and missile age that was dawning.

The last wartime Persings sat in motorpools across occupied Germany, their olive drab paint flaking, their barrels capped against the rain. The army was demobilizing, shrinking back into peaceime comfort. But the engineers at Detroit Arsenal and the veterans at Fort Knox had a premonition. History rarely allowed democracies to rest for long.

That premonition came true on June 25th, 1950. When North Korean forces surged across the 38th parallel, their Soviet supplied T34/85 tanks crushed the Republic of Korea’s lines in days. US occupation troops in Japan, light on armor, heavy on complacency, were rushed to Korea in desperation. The first American tanks to land at Busan were not Persings or patterns.

They were worn out M24 chaffies, the same light tanks that had been outclassed even in 1945. Their 75 mm guns bounced off the T-34’s sloped armor like pebbles. Infantry men watched helplessly as their shells ricocheted while the North Koreans cut through roadblocks with mechanical precision.

In the chaos, the Ordinance Corps sent urgent telegrams to the United States. request immediate shipment of M26 Persings and 90 mm ammunition. T34s superior to all tanks presently in theater. Within weeks, the first Persings, relics of the European War, were pulled from depots in Japan and Okinawa. They were battered, their engines weary, but their guns were still true. Mechanics worked around the clock to replace cracked road wheels and leaking radiators.

By late July, Task Force Smith had fallen, Téjon was in flames, and the Persings were being loaded onto transports bound for Busan. When they rolled ashore, they were met by tank crews who had never seen one before. To them, the Persing was a legend. The tank that had killed the Panthers, the weapon that symbolized American redemption.

At the front, that legend was put to the test. In early August 1950, outside the town of Masan, a platoon from the 75th Tank Battalion engaged a column of North Korean T34s advancing along the valley road. The terrain was claustrophobic. Rice patties, hills, smoke from burning villages.

Sergeant Stanley Clark’s M26 took position behind a burm, its gunner aligning the crosshairs at 900 yd. Target T34 left of the bridge,” the gunner called. The 90 mm gun fired. The round struck the T34’s turret, blowing it clean off in a fireball that lit the valley. Hit confirmed. Within minutes, the Persings had destroyed three more tanks.

The remaining T34s retreated, their confidence shattered. For the first time in the Korean War, American crews realized they could fight on equal terms. But victory came with a warning. The M26’s engine overheated constantly. Its transmission failed on the steep Korean hills, and its heavy weight bogged it down in rice patties.

Mechanics cannibalized parts, using captured Japanese trucks to haul transmissions. The Persing had power but no endurance. A lesson the army should have remembered from Europe. By late 1950, as General Douglas MacArthur pushed north toward the Yaloo River, newer M46 patns began arriving from the States. Persings refitted with more powerful engines and improved drives.

The M46s could climb the hills where the M26s stalled, and their speed gave the crews a fighting chance in Korea’s mountainous terrain. Still, the Persing earned its second reputation the same way it earned its first, in blood and mud. At the Chongchon River, under sub-zero temperatures, one Persing held off an entire Chinese tank column through the night, firing until its barrel glowed red.

When it finally ran out of shells, the crew destroyed their own tank rather than let it be captured. To the young tankers who followed, the Persing was an anacronism and an idol. An echo of the armored giants of Europe now fighting in Asia’s hills. While the Persings fought in Korea, the engineers at Detroit Arsenal studied every field report.

The same debates that had consumed the army after Normandy reemerged in the new decade. The lesson of Cologne, the cost of being technologically unprepared, was burned into every ordinance officer’s mind. Chief engineer Harold Young summarized the findings bluntly in a 1951 memo. The Persing demonstrated the necessity of firepower par.

The cost of delay in design and production is measured not in dollars but in men. Under his supervision, the M46 gave way to the M47 and M48 patterns. Each iteration faster, tougher, and more maintainable. The Persing had been a bridge, the experimental step between the fast undergunded Shermans and the modern main battle tanks that would define the next half century.

In the training grounds of Fort Knox, new tank crews learned their craft on Persings that had survived both wars. instructors used them as cautionary examples. “This tank killed panthers,” one sergeant would say, patting the side armor. “But she came too late because men argued instead of deciding.” “Don’t ever let that happen again.” The lessons filtered up into doctrine.

The armored school rewrote its manuals to emphasize combined arms, fire superiority, and industrial readiness. Never again would the army send tankers to fight without equivalent weapons. At the same time, historians began re-evaluating the Persing’s place in the war. The old myths of the Sherman’s sufficiency dissolved under the weight of postwar analysis.

The US strategic bombing survey, cross-referenced with German war diaries, revealed the ugly truth. For every Panther destroyed in Normandy, several Shermans had been lost. The Persing could have saved thousands if it had existed a year earlier. In 1952, the Army officially redesated the M26 as a medium tank, aligning it with the patent lineage.

It was a bureaucratic act, but also a symbolic one, an acknowledgement that America’s heavy tank had become the foundation of a new philosophy. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, in the ruins of the old Reich, a different army watched closely. The newly formed Soviet occupation forces studied the Persings left behind after the war, just as they had studied captured panthers and tigers.

In the archives of NYI48, a Soviet tank design bureau near Kubinka, engineers dissected a captured Persing and compared it to their own T44. Their conclusion, declassified decades later, was blunt. The American M26 demonstrates excellent crew ergonomics and optical systems.

Its fire control and reliability exceed those of the German Panther. Its armor and gun equal our own T44 in protection and surpass it in comfort. That single analysis helped drive the development of the T-5455 series, the tank that would become the backbone of Soviet armor for the next generation. In an ironic twist, the Persing had helped shape not only the future of American tanks, but the tanks it would one day face.

By 1953, the Korean War was grinding to its uneasy stalemate. The Persings that survived were worn out, patched with field repairs, and repainted in hasty camouflage. Many were left behind as static defenses, their barrels pointed north across the DMZ. A few were shipped home to training schools, to scrap, to museums.

One, the famous fireball that had fought in Cologne, ended up at the Aberdeen proving ground. Visitors would walk past its scarred armor, unaware they were looking at the steel ghost of a turning point. Historians later called the Persing the tank that arrived too late to change the war, but early enough to change the world.

It had closed a technological gap that had haunted America since Casserin Pass and Normandy. It forced generals to reckon with the cost of underestimating the enemy, and it set the stage for a new kind of warfare, one fought not in desperation, but in preparation. When the M60 pattern rolled out in the 1960s, its engineers traced its lineage directly back to the M26’s design papers.

And when the M1 Abrams debuted decades later, its 120 mm smooth boore and composite armor carried the same philosophy born from those desperate days in 1944. Never again should an American tanker go into battle outgunned. In 1985, 40 years after the Persing duel at Cologne, a reunion of the Third Armored Division was held in Fort Knox.

Among the guests was Sergeant Clarence Smooyer, now an old man with steady hands and a quiet voice. On display behind him stood a restored M26 Persing, polished and silent. When asked what he remembered most, Smoyer smiled faintly. “The sound,” he said, “when that 90 fired, it wasn’t like a Sherman. It was final. You knew the fight was over.

” He touched the side of the tank, the same armor that had saved his life on that March morning in 1945. Around him, the younger soldiers of a new generation listened in respectful silence, their olive uniforms different, but their profession unchanged. The Persing, Smoyer continued, wasn’t perfect, but it gave us a fighting chance. That’s all we ever wanted.

Outside the wind blew across the training fields where patterns and abs now thundered. Inside the museum the Persing stood beneath its plaque. M26 Persing, the bridge between wars. It was more than a machine. It was the embodiment of a lesson carved into the memory of every soldier who had fought from Normandy to Busan. That progress bought too late is paid for in blood. And that steel, no matter how strong, must always arrive before the battle, not after. And so, in the long shadow of the Persing, the world’s armies learned the truth that engineers at Aberdeen and tankers in Cologne had understood decades earlier. In war, there are no second chances for those who build too slowly.

News

CH2 When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When America Outsmarted the Fortress Islands of the Pacific

When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When…

CH2 Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter And Flew Home And Shocked the World – Is It True Or Just A Myth

Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter…

CH2 3,000 Casualties vs 3 – The Deadliest Trap of WW2 Laid By One 19-Year-Old’s Codebreaking and a Midnight Naval Ambush

3,000 Casualties vs 3 – The Deadliest Trap of WW2 Laid By One 19-Year-Old’s Codebreaking and a Midnight Naval Ambush…

CH2 The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed

The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed By 1944, Europe had…

CH2 The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While Other Allies Took Cover First

The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While…

CH2 ‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a Death Trap

‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a…

End of content

No more pages to load