Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

At 9:58 on April 8th, 1940, Lieutenant Commander Gerard RP stood on the bridge of HMS Glowworm, watching a massive gray silhouette emerge from the Norwegian fog. The German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper was closing at high speed. 35 years old, 5 years commanding destroyers, zero chance of survival.

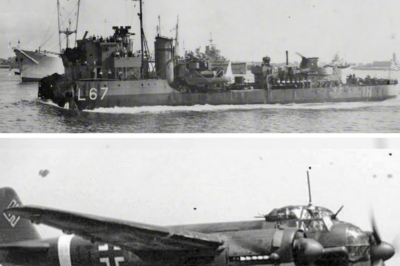

The Admiral Hipper displaced 14,000 tons and carried eight 8-in guns. HMS Glowworm displaced 1350 tons. The German cruiser outweighed the British destroyer 10 to1. Every shell from Hipper’s main battery weighed twice as much as anything Glowworm could fire back. 3 hours earlier, Glowworm had been alone in heavy seas north of Norway. A man had gone overboard 2 days before during a storm.

RP had spent 18 hours searching, found nothing. The crew was exhausted. The ship had fallen behind the battle group she was supposed to be escorting. Renown, the battle cruiser, was somewhere over the horizon. Glowworm was trying to catch up. When lookout spotted smoke at 0800, two German destroyers, Z11 burned von Arnum and Z18 Hans Ludman.

They were packed with invasion troops heading for Tronheim. Part of operation Vzerubong. The German invasion of Norway was happening right now, and RP had stumbled into it blind. Glowworm opened fire at 8,000 yd. The German destroyers fired back, then turned north, running. RP knew what they were doing, leading him towards something bigger, but he gave chase anyway.

If German heavy units were at sea, the Admiral Ty needed to know. He sent a contact report, then kept following. The weather was brutal. 30-foot swells, wind howling across the deck. Glowworm was rolling so hard that men were getting thrown against bulkheads. Two more sailors went overboard. The ship’s gyro compass failed. They were steering by magnetic compass in a snowstorm.

Then at 9:50, the fog lifted for 30 seconds. Admiral Hipper was there less than 10,000 yards away. Massive, modern, fast. One of Germany’s newest heavy cruisers. Her 8-in guns could punch through Glowworm’s thin plating like paper. Her armor could shrug off anything the destroyer fired back. Hipper’s first salvo landed 8 minutes later. Range 8,400 m.

The fourth salvo hit Glowworm’s bridge. The director control tower flooded. Forward 4.7 in gun destroyed. Radio room wrecked. Captain’s cabin obliterated. The mass came down and shorted the electrical system. Glowworm siren turned on. Started wailing. Wouldn’t stop. Root made smoke and turned into it. Bought himself 90 seconds.

Ordered the torpedo crews to prepare all 10 tubes. Glowworm carried quintuple mounts, two sets of five torpedoes each. Brand new design. The ship had been the test platform. If you want to see whether RP’s torpedoes could stop a ship 10 times his size, please hit that like button. It helps us share more stories of courage at sea. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to RP.

When Glowworm emerged from the smoke, Hipper was waiting. Range 800 m. Point blank. The German cruiser’s secondary battery opened up. 4.1 in guns. Firing as fast as the crews could load. Glowworm’s engine room took hits. Steam pressure dropping, speed falling. RP fired all 10 torpedoes at 400 yardds, close enough to see faces on Hipper’s deck. Then he watched. 10 white wakes racing toward the massive gray hull.

One passed within feet of Hipper’s bow. The rest missed. All 10. The cruiser turned just enough. Every single torpedo ran clear. Gloworm had three guns left firing. Hipper had 20. The bridge was gone. The engine room was flooding. Men were dying in spaces RP couldn’t reach. His ship was being torn apart by shells that weighed more than his crew.

And RP made a decision no commander had made in modern naval warfare. He ordered hard right rudder, pointed glowworms bow straight at the massive cruiser towering above him, and opened the throttles. Hipper’s captain saw it too late. Capitan Zuz Helmut Haya tried to turn his cruiser to ram first, but 14,000 tons doesn’t answer the helm like 1350.

The heavy cruiser was still swinging when Glowworm closed the final 200 yd. Every gun on Glowworm that could still fire was shooting. The siren kept wailing. The ship was trailing smoke and flame. Speed down to 20 knots, but still accelerating. Rupe stood on what was left of his bridge and aimed for Hipper’s starboard side just a anchor. Impact came at 1013.

Glowworm’s bow hit the cruiser’s armored belt and crumpled instantly. The entire forward section folded back like paper, but the destroyer’s momentum carried 1300 tons of steel down the length of Hipper’s hull, scraping, tearing, ripping. 100 ft of armor plating came away. Hipper’s forward starboard torpedo mount was crushed and torn off completely.

Two massive holes opened in the cruiser’s hull below the water line. One German sailor was swept overboard by the destroyer’s superructure as it ground past. Two compartments started flooding immediately. 500 tons of seawater poured into Hipper’s forward spaces before damage control teams could isolate the breaches.

The cruiser’s freshwater system ruptured. Both main tanks punctured. No fresh water meant no boilers at full capacity within hours. Hipper started listening to Starbird. Not enough to be critical, but enough that Hya knew his ship was hurt. Glowworm pulled clear at 10:15. The destroyer’s bow was gone. Just gone.

The forward section ended in twisted metal and exposed compartments, but the engine room was still running. One gun was still firing. Petty Officer Walter Scott’s crew on the aft 4.7inch mount put three more rounds into Hipper from 400 yardds. Hipper’s secondary battery responded. 20 guns firing at a target they couldn’t miss. Shells walked up Glowworm from stern to bow. The aft gun went silent.

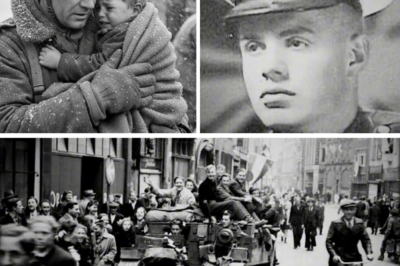

The engine room took another hit. Steam pressure collapsed. All power failed. Fire broke out amid ships. The boiler spaces were flooding. Men were trapped below decks in spaces that were filling with superheated steam and seaater. Rupe gave the order to abandon ship at 10:17. The crew started going over the side into the Norwegian Sea. Water temperature was 38°.

Survival time in those conditions was maybe 20 minutes. The men had life jackets, but no time to launch boats. They jumped into 30foot swells. Glowworm was listing heavily to port. Her torpedo tubes were underwater. She was burning from stem to stern. The remaining crew climbed onto the keel as the ship rolled.

Some jumped, some waited. Rupe moved among them, helping men into life jackets, pushing them toward the water, making sure they went over the high side where the swells wouldn’t smash them against the hull. Then at 10:24, the boilers exploded. The blast tore Glowworm in half. The bow section that was left sank immediately.

The stern hung vertical for 15 seconds. Men were still clinging to it. Then it slid beneath the surface. 149 men had been aboard. 118 were now in the water dying. Hi made a decision that would define him for the rest of his life. He ordered Admiral Hipper to stop in the middle of a combat zone with his ship damaged and taking on water. with a British battle group somewhere over the horizon.

He positioned his cruiser so the current would carry survivors toward the hull. Then he ordered every available man on deck. German sailors threw ropes and cargo nets over the side. Soldiers from the invasion force helped pull men up. The survivors were covered in fuel oil, hypothermic, exhausted. Many grabbed ropes but couldn’t hold on. Their hands were too cold. Their muscles wouldn’t respond.

They slipped back into the sea and vanished. Rope was in the water helping his crew. Witnesses saw him pushing men toward the ropes. Getting life jackets onto sailors who’d gone over without them. He was one of the last to reach Hipper’s hull. German sailors threw him a line. He grabbed it. They started pulling him up the side of the cruiser.

He made it halfway. Then his hands opened. He fell back into the Norwegian Sea and disappeared. 31 survivors made it aboard Admiral Hipper. Lieutenant Robert Ramsay was the only officer. The rest of Glowworm’s crew was gone. Hi had the survivors brought to his wardrobe, fed them, gave them dry clothes.

Then he did something unprecedented. He told them their captain was a brave man and he sat down to write a letter that would travel through the International Red Cross to London recommending that Lieutenant Commander Gerard Rupe be awarded the Victoria Cross. But there was something the survivors didn’t know yet. Something that wouldn’t become clear for 5 years.

What Rupee’s decision on that bridge had actually accomplished. Admiral Hipper limped into Tronheim Harbor 12 hours after the ramming. The damage looked manageable from the dock. 100 ft of armor plating missing, torpedo mount destroyed, two holes patched with emergency plates. The cruiser was still afloat, still operational. German command considered sending her back to sea within days.

Then the damage control reports came in. The ramming had done more than tear away armor. It had buckled internal frames across 40 ft of the ship’s structure. The keel was twisted. Stress fractures ran through three bulkheads. Hipper’s hull had been bent by the impact and the entire forward starboard section was compromised. She could float.

She could not fight. The Norwegian campaign needed every major surface unit. Germany had committed its entire fleet. Charhorst and Gennisau were covering the northern landings. Blucer had been sunk by Norwegian coastal guns in Oslo fjord on the same day Glowworm went down. Lut was damaged. The criggs marine was stretched to breaking.

Admiral Hipper was supposed to provide fire support for the Tronheim assault, then interdict British reinforcement convoys, then returned to Germany to rearm and join the Atlantic raiding campaign. Instead, she sat in Tronheim taking on temporary repairs while British forces consolidated in Norway. The cruiser left Tronheim on April 14th, 6 days late. She didn’t head for the Atlantic. She headed straight for Vilhelms Hav.

The dockyard workers there took one look at the damage and issued their report. Hipper would need complete structural repairs. New armor plate, new torpedo mount, new bow section fabrication. The freshwater system needed total replacement. The list went on. Hipper went into dry dock on April 20th. She stayed there until July, 3 months. During those 3 months, the entire strategic situation in the Atlantic changed.

British convoys that Hipper was supposed to raid reached port safely. German surface raiders that Hipper was supposed to support operated alone. The cruiser that was supposed to be Germany’s most active commerce raider in mid 1940 sat in a shipyard instead. The cost was calculated years later by naval historians. Hipper missed four major convoy operations.

She missed the chance to intercept troop transports heading to France. She missed supporting Charhost and Ganisanau during their Atlantic sorty in June. One British destroyer had removed a German heavy cruiser from the board for 90 days during the most critical phase of the war at sea. But nobody in Britain knew. The 31 survivors were in German prisoner of war camps.

Lieutenant Ramsay was separated from the crew and held in an officer camp. The enlisted men were scattered across three different facilities. German security kept them isolated. None of them knew what had happened to Hipper after the rescue. None of them knew the cruiser had been knocked out of the war. The Admiral T knew Glowworm was lost.

They knew she’d engaged enemy destroyers and a heavy cruiser. They had RP’s contact report from 958. Then nothing. The assumption was that Glowworm had been sunk in a conventional gunnery action, overwhelmed by superior force. The loss was noted. The ship was marked down as destroyed by enemy action. The file was closed. RP’s family received notification in May 1940. Missing and presumed dead.

No details available. His wife Faith received a telegram with 12 words. The Navy sent condolences. There was no mention of the ramming. No mention of the damage to Hipper. No mention of Hi’s recommendation. That recommendation was sitting in a Red Cross office in Geneva, waiting for the right channels to process it through diplomatic protocols that took years during wartime.

The survivors spent their entire captivity not knowing if anyone would ever know what they’d done. Ramsay spent 5 years in of camps wondering if the story of Glowworm’s last fight would die with him. The enlisted men spent 5 years wondering if their families even knew they were alive. German camp administrators weren’t required to report prisoner of war status until after interrogation and processing.

Some families didn’t receive notification their sons or husbands were alive until 1941. Meanwhile, the war moved on. Norway fell, France fell, the Battle of Britain happened, the Blitz happened. Hundreds of ships were sunk on both sides. Thousands of men died at sea. Glowworm became one name in a very long list.

And then something happened that would bring the story back. Something that would turn a forgotten destroyer into a symbol. But it would take five more years. 5 years of silence while the men who knew the truth sat in camps behind barbed wire wondering if Gerard Rupe sacrifice would ever be recognized. May 8th, 1945, Germany surrendered. The prisoner of war camps opened.

Lieutenant Robert Ramsay walked out of O flag 7c in Bavaria carrying nothing but the clothes on his back. 27 years old, 5 years in captivity, the only officer who survived HMS Glowworm. He reached Britain on June 2nd. The Navy debriefed him for 3 days. They asked about camp conditions, about German interrogation methods, about what intelligence he might have gathered.

Standard questions for returning prisoners of war. On the fourth day, Ramsay asked when Lieutenant Commander RP would receive his postumous recognition. The Navy liaison officer looked confused. Recognition for what? Glowworm had been lost in action against superior force. RP had done his duty. The ship was listed as destroyed in conventional combat. What recognition did Ramsay think was appropriate? Ramsay explained what happened.

The ramming, the damage to Admiral Hipper, RP’s decision to attack rather than withdraw. the German captain’s words to the survivors. Hi’s promised to recommend root for Britain’s highest decoration. The liaison officer wrote it all down, then told Ramsay the Navy would investigate. The problem was evidence. Ramsay was one witness.

The 30 other survivors were enlisted men scattered across different camps. It would take weeks to collect their statements. German records were in chaos. The marine archives were either destroyed or seized by Soviet forces. Admiral Hipper’s logs were missing. Hy himself was missing.

Nobody knew if he was dead or in Soviet custody or simply hadn’t been processed yet. The Admiral T was skeptical. A destroyer ramming a heavy cruiser wasn’t standard tactics. It sounded desperate. Maybe RP had panicked. Maybe the collision was accidental during the battle. Ramsay’s story had the collision happening after all torpedoes missed, after the ship was crippled. That made it sound like suicide, not tactics.

The Navy preferred heroes who followed doctrine. And there was politics. The war in Europe was over, but the Pacific was still burning. Resources were focused on Japan. The Navy was dealing with demobilization. Thousands of ships, hundreds of thousands of men. The administrative system was overwhelmed. One destroyer sunk 5 years ago.

Wasn’t a priority. Ramsay tried another approach. He contacted Rupe’s widow. Faith. Rupe had spent 5 years not knowing how her husband died. Just missing and presumed dead. Now Ramsay told her the truth. The ramming, the rescue, the German captain’s respect. She deserved to know. Faith Rupe wrote to the Admiral Ty. She requested recognition for her husband’s actions. The Navy responded politely.

They would investigate when resources allowed. The letter went into a file with thousands of other requests from thousands of other families. Everyone wanted their husband or son or father recognized. Everyone had a story about heroism. The Navy couldn’t process them all. June became July. July became August. The atomic bombs fell. Japan surrendered. The war ended.

Ramsay waited. The other survivors came home and gave their statements. 31 depositions, all consistent, all describing the same action. The ramming was deliberate. Rupe had ordered it. The siren had been wailing. One gun kept firing. Hipper had stopped to rescue them, but still no German confirmation. No one had found Hay. No one had found Hipper’s logs.

The Admiral had British witnesses, but no objective evidence. And there was another problem. If the Admiraly recognized Rupe with aostumous Victoria Cross based solely on British testimony, it would look self- serving like Britain was inventing heroes to compensate for the disaster of Norway.

September 1945, 6 months after Germany surrendered, the files on Glowworm sat in an Admiral office waiting for something. Some piece of evidence that would make the case undeniable. Some confirmation that what Ramsay described had actually happened. Some proof that RP’s action was real. And then in October, a letter arrived in London.

It had been processed through the International Red Cross in Geneva, sent through diplomatic channels that took months to clear. Written in August 1940 by a German naval officer. It had taken 5 years to reach its destination. The letter was from Capitan Zurzi Helmouth High and it recommended that Lieutenant Commander Gerard RP be awarded the Victoria Cross.

The letter was 5 years old, but the words were fresh. Hi had written it on August 20th, 1940, 12 days after the action. He’d addressed it to the British Admiral Ty through Red Cross channels. The diplomatic machinery of wartime had delayed it for 5 years, but now it was here. Hi’s testimony was detailed.

He described the engagement from Hipper’s bridge, the fog, the German destroyers calling for help, glowworm’s decision to pursue, the gunnery exchange, 10 torpedoes fired at point blank range, then the ramming. Hy wrote that Rupe had displayed extraordinary courage in engaging a vastly superior warship, that the decision to ram was deliberate and executed with skill, that the British commander had fought his ship to the end with exceptional valor.

The letter included technical details only someone on Hipper’s bridge would know. The range when Glowworm emerged from the smoke, the number of hits scored on the destroyer, the exact location where Glowworm struck Hipper’s hull, the extent of the damage.

Hi wrote that his cruiser had required three months of repairs, that the ramming had removed Admiral Hipper from operations during a critical period, that one British destroyer had achieved what an entire squadron might not have. Then Hy made his recommendation. He stated that Lieutenant Commander Rupe’s actions met every standard for Britain’s highest military decoration that the courage displayed deserved recognition regardless of the outcome. That warriors on both sides should honor exceptional valor when they witnessed it.

He requested that the British authorities consider Rupe for the Victoria Cross. The Admiral legal section examined the letter for 2 weeks. They verified the Red Cross stamps. They confirmed the signature matched Hi’s pre-war correspondence. They checked the dates against known events. Everything aligned. The letter was authentic.

On July 6th, 1945, the Admiral T published a recommendation in the London Gazette, the official journal of record for British military honors. The text described Glowworm’s action on April 8th, 1940. It noted that full information had only recently been received. It stated that Lieutenant Commander Gerard Broadme RP was awarded the Victoria Cross postumously. The citation explained the circumstances.

Glowworm proceeding alone in heavy weather toward a rendevous. Meeting and engaging two enemy destroyers, pursuing them toward their supporting forces, citing the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper closing at high speed, sending an enemy report, fighting the ship to the end against overwhelming odds, finally ramming the enemy with supreme coolness and skill. The citation didn’t mention that only 31 men survived.

It didn’t describe RP drowning while helping rescue his crew. It didn’t explain the 5-year delay or the letter from a German captain. Those details would come later in the full account. The official citation focused on the action itself. The decision, the execution, the cost. RP became the first Victoria Cross recipient of the Second World War. Not the first awarded, the first earned. April 8th, 1940.

before Dunkirk, before the Battle of Britain, before the Blitz, before most people realized how long or how terrible the war would become. The first man to earn Britain’s highest decoration in a conflict that would produce 181 more, and he was one of only three men in the entire war to receive the Victoria Cross based on enemy recommendation.

The other two cases involved German officers recommending British airmen for extraordinary courage. But RP was the first, the beginning of a tradition that said valor transcended nationality, that warriors could recognize courage in their opponents, that honor existed even in mechanized warfare.

Faith RP received the medal on February 12th, 1946, a ceremony at Buckingham Palace. King George V 6th presented the bronze cross on its crimson ribbon. The king spoke briefly about Rub’s courage, about the sacrifice of Glowworm’s crew, about the debt owed to men who fought against impossible odds. Faith kept the medal for the rest of her life.

She died in 2001 at age 94. The Victoria Cross passed to private ownership. It’s not on public display. Most people don’t know where it is now. Just like most people don’t know the full story of HMS Glowworm, but there’s one place that remembers, one place where the story lives on.

The Norwegian island of Kaya sits 60 mi northwest of Tronheim. Population in 1940 was 14. Fishermen mostly, rocky terrain, no trees. The kind of place maps barely marked. The coordinates where HMS Glowworm went down are 4 miles southwest of that island, 64° 27 minutes north, 6° 28 minutes east. The wreck lies in Norwegian territorial waters, 240 m down. Cold water preservation keeps the hull relatively intact.

Norwegian authorities declared it a war grave in 1995. No diving allowed, no salvage permitted. 118 men are still down there. For 60 years, nobody in Norway knew the story. The battle happened during the chaos of the German invasion. Norwegian forces were fighting in the south. The tiny population on Kaya saw smoke on the horizon that morning, heard distant explosions, then nothing.

German forces occupied the area within days. Nobody asked questions. The fishermen didn’t learn what they’d witnessed until after the war. But in 2024, Norway decided to build a memorial. The Norwegian government, the Royal Navy, Veterans Organizations, they commissioned a monument on Kaya, a granite stone facing southwest toward the coordinates, inscribed with the names of all 149 crew members.

The dedication was scheduled for April 8th, 2024, 84 years to the day. The memorial project brought attention the story had never received. British naval historians wrote articles. Norwegian newspapers covered the battle in detail. Documentaries were produced. For the first time, the full account reached a broad audience.

The ramming, the rescue, Hi’s letter, the 5-year delay, the Victoria Cross, all of it. Researchers found Hi’s post-war records. He’d survived the war, served on Admiral Hipper through 1945. The cruiser made several more Atlantic sorties after the repairs, raided convoys, fought at the Battle of the Barren Sea in December 1942, survived until the end.

Hy retired from the German Navy in 1947, died in 1970. He never spoke publicly about recommending Rupe for the Victoria Cross. His family found the correspondence after his death. Admiral Hipper’s fate was different. The cruiser survived the war, but barely. She was bombed multiple times in Keel during 1945. Heavily damaged by RAF attacks in February and April. When Germany surrendered, Hipper was a burnedout hulk sitting on the bottom of Keel Harbor.

The British found her there during occupation. They raised the wreck in 1948, cut her up for scrap, sold the metal. Nothing remains except photographs and a few artifacts in German naval museums. The 31 survivors scattered after the war. Most returned to civilian life. A few stayed in the Navy.

Lieutenant Ramsay served until 1952, retired as a commander. He attended several reunions of glowworm survivors over the decades, gave interviews, made sure the story was preserved. He died in 1989. The last survivor died in 2007. Nobody named another ship HMS Glowworm. The Royal Navy has traditions about reusing names from ships lost in action.

Ships that died fighting usually get their names carried forward to new vessels. But glowworm never got a successor. The name died with the ship. Some historians think it was deliberate that the Admiral Ty wanted that specific Glowworm to stand alone. The ship that rammed a cruiser, the ship that earned the first Victoria Cross of the war. Navalmies still study the action.

It appears in textbooks about destroyer tactics, about decisions under fire, about when conventional doctrine should be abandoned. The case is unusual because ramming was obsolete by 1940. The tactic belonged to the age of wooden ships and iron men. Nobody rammed in modern warfare. Shells and torpedoes fought battles at ranges measured in miles, not feet.

But Rupe had no shells left that could hurt Hipper. His torpedoes had missed. His ship was dying. And he chose the oldest tactic in naval warfare, the most primitive, the most direct. He pointed his bow at the enemy and rammed. The question asked in navalmies is whether it was the right decision. Whether ramming was tactically sound or simply desperation.

Whether Rupe saved his men or sentenced them to death. The answers vary, but everyone agrees on one thing. It worked. Rupe had three options when his torpedoes missed. He could surrender. He could try to break contact and run, or he could ram. None of them were good. All of them probably ended with Glowworm at the bottom.

Surrender meant stopping the ship, raising white flags, letting Hipper close alongside, then hoping the Germans would accept. But Glowworm was a warship in a combat zone during an active invasion. Rupe had already sent a contact report identifying German heavy units. He’d fired on destroyers carrying invasion troops. Hipper couldn’t afford to take prisoners. Not with British battle groups converging. The cruiser would have sunk Glowworm anyway.

Surrender bought nothing. Running meant turning away from Hipper and trying to build distance through the smoke. At full speed in good conditions, Glowworm could make 36 knots. Hipper could make 32. The destroyer was faster on paper, but Glowworm’s engine room was damaged. She was making 20 knots.

Maybe Hipper would have caught her in 15 minutes, then finished her with 8-in guns at long range. Running bought time to die slowly. Ramming bought a chance to hurt the enemy, not to survive. That ship had sailed when the first 8-in shell hit the bridge, but to make the Germans pay for Glowworm, to damage Hipper badly enough that the cruiser couldn’t continue operations, to remove her from the board, even if it cost every man aboard the destroyer. The mathematics were brutal. 149 British lives for 90 days of German

combat capability, one destroyer for three months of a heavy cruiser. The exchange rate was terrible in human terms, but strategically it worked. Hipper missed the entire Norwegian campaign, missed the Atlantic raiding season, missed convoy operations. One ship sacrifice bought time for dozens of convoys to cross safely.

But Rupe didn’t know that would happen. He couldn’t have known Hipper would need 3 months in dry dock. He couldn’t have known about the structural damage or the strategic impact. All he knew was his ship was dying and he could either die uselessly or die causing damage. He chose damage.

The decision reveals something about command in desperate situations, about what happens when doctrine fails, about what officers do when every option is terrible. Rope didn’t follow any manual. There was no procedure for ramming in modern destroyer tactics. He invented his response in real time while his ship was being destroyed around him.

Some historians argue it was tactical brilliance. Others call it brave desperation. The truth is probably both. Rope saw an opportunity in the moment when Hipper emerged from the smoke. The range was close. The cruiser was slow to turn. The geometry favored ramming. He took the shot.

Whether it was genius or last resort doesn’t change the outcome. What matters is that 118 men died executing that decision. They didn’t get to vote. They didn’t get consulted. Rupe gave the order and the crew followed because that’s what naval discipline demanded. Some of them probably understood what ramming meant. Others probably didn’t realize until impact. Either way, they stayed at their posts.

The engineers kept the engines running. The gunners kept firing. Nobody abandoned station. That’s the part navalmies focus on. Not whether ramming was smart tactics, but whether the crews discipline under those conditions represents something worth teaching. Whether modern sailors need to understand that level of commitment.

Whether that kind of sacrifice still has meaning in an era of missiles and computers and pushb button warfare. The answer most instructors give is yes. Because technology changes, but humans don’t. Ships still break. Systems still fail. Officers still face decisions where every option is terrible. And when that happens, they need examples. They need to know someone else faced impossible choices and acted anyway. They need Gerard Rupe.

But there’s one more question, one that only the families can answer. Was it worth it? Faith RP never answered that question publicly. She accepted the Victoria Cross. She attended memorials. She corresponded with survivors, but she never said whether she thought her husband’s decision was worth 118 lives. Some questions don’t have answers families should have to give. The survivors had their own answers.

Most of them said RP did what he had to do, that the alternative was dying for nothing, that at least the ramming achieved something. A few disagreed, thought RP should have surrendered or run, thought some of them might have survived as prisoners, but even those who questioned the decision never questioned RP’s courage, never suggested he acted from anything except duty.

What’s certain is what would have been lost if Glowworm had surrendered or been sunk without fighting. The story would have ended with a destroyer overwhelmed by superior force. a footnote in the Norwegian campaign. One more ship on the casualty list. Nobody would remember the name. Nobody would build memorials.

Navalmies wouldn’t teach the case. Instead, HMS Glowworm became something else. Proof that small ships could hurt big ones. That determination mattered as much as firepower. That the oldest tactic still worked when everything modern failed. The story survived because it was exceptional.

Because RP’s decision was so unusual that even his enemies felt compelled to document it. Hi’s letter ensured that without German confirmation, the ramming might have been dismissed as British propaganda. Exaggeration, a story invented to make defeat sound heroic. But Hy wrote the truth, described what he witnessed, recommended his opponent for the highest honor. That act of respect guaranteed the story would endure.

And it has endured. 84 years later, people still know HMS Glowworm, still study the action, still debate RP’s decision. The memorial on Kaya ensures a new generation will learn the names of 149 men who sailed into fog off Norway and never came home. There’s a lesson in that, about how we remember wars. Most battles are forgotten.

Most ships sink into obscurity. Most men who die at sea leave no mark beyond family memories. But a few stories survive. The exceptional ones. The impossible ones. The ones that show humans doing things that seem beyond human capacity. Rupe pointed a 1300 ton destroyer at a 14,000 ton cruiser and gave the order to Ram. That decision deserves remembering.

Not because it was perfect tactics, not because it saved everyone, but because it was human. A man facing impossible circumstances and choosing to act. Choosing to hurt the enemy, even if it cost everything. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people.

Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about destroyer commanders and sailors who made impossible choices. Stories about ramming and courage and sacrifice that most people have never heard. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from.

Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching. And thank you for making sure Gerard Rupe and his crew don’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

CH2 The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days Most people have no idea that one…

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

CH2 They Mocked His “Pistol Only Crawl” — Until He Took Out a Machine Gun Crew on D-Day

They Mocked His “Pistol Only Crawl” — Until This Brooklyn Soldier Took Out a Machine Gun Crew on D-Day And…

End of content

No more pages to load