German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is…

The morning of June 4th, 1944, was ordinary in the cold, gray expanse of the North Atlantic—or at least it should have been. U-55, a Type VIIB U-boat, glided silently beneath the choppy waves, its steel hull cutting through the water as Oelotant Paul Meyer crouched at the hydrophone station. His headset pressed tight, he listened intently to the faint, rhythmic pulse of the ocean, to the creaks and groans of the submarine itself. Every sound had a meaning, every silence an omen, and that morning the silence was more unsettling than anything Meyer had ever encountered in his years beneath the sea. The hydrophone, normally a tool for detecting distant convoy engines or enemy escorts, picked up something that defied all the training, doctrine, and experience he had accumulated. There was no boom, no explosion, no thunderous detonation that might signal an approaching depth charge. Instead, there was a scraping noise, subtle and unnatural, as if metal rods were being dragged across the hull from above. Then—three seconds of nothing. Absolute silence.

The men around Meyer exchanged uneasy glances. They were veterans; most had seen the terrifying power of depth charges, the way explosions could twist the hull, rattle the instruments, and leave a lingering vibration that could be felt in their bones. They had survived the loud, violent terror of the Atlantic—countless engagements where the sea itself seemed alive with danger—but this was different. Quietness, they realized, could mean death in a way that thunder never could. The vessel’s commander barked orders with a clipped urgency, the men scrambling to assess the threat, but there was no visual clue, no telltale wake or plume, nothing to indicate that the invisible menace had already been unleashed.

That menace had a deceptively simple name: the hedgehog. The Allies had developed it over months of research and trial, a weapon designed to circumvent every limitation the depth charge had imposed on anti-submarine warfare. Its mechanism was almost quaint in design: 24 spigot mortars arranged in four cradles of six projectiles, mounted on the foredeck of escort vessels. Yet within that simplicity lay a terrifying effectiveness. The hedgehog did not explode at a pre-set depth. It did not rely on guessing where the submarine might be, nor did it wait for a ship to pass over the target and hope the vessel had not slipped away in the interim. Instead, it fired projectiles ahead of the ship, creating a lethal pattern into which a submarine might inadvertently drift—or be forced to endure. Any contact with a U-boat’s hull triggered instantaneous detonation. There were no false successes, no comforting explosions that fooled crews into believing they had inflicted damage. The hedgehog was quiet, precise, and lethal.

To understand the terror it inspired, one had to consider the state of the Battle of the Atlantic in early 1943. For nearly four years, German U-boats had dominated the waters, striking at the arteries of Allied supply. From September 1939 through March 1943, they sank over 14 million tons of Allied shipping, a staggering figure that spoke to the lethal efficiency of the wolf packs patrolling the North Atlantic. In June 1942 alone, U-boats claimed 637,000 tons of British merchant shipping, leaving convoys and their escorts scrambling to adapt to a predator they could neither see nor predict with certainty. Early countermeasures, including the convoy system and basic sonar, provided some mitigation but did not eliminate the fundamental threat. Submarines could approach underwater, fire torpedoes, and slip away before escorts had any chance of effective retaliation.

The depth charge, which had long been the primary anti-submarine weapon, had critical flaws. These large, barrel-shaped explosives, weighing 300 to 600 pounds and filled with high explosives like Torpex or amatol, relied on precise estimations of depth. Escorts would detect a submarine using sonar—referred to by the British as ASDIC—and race to the target area, releasing depth charges set to detonate at a predetermined depth. But if the depth estimate was off by even fifty feet, the charge might explode harmlessly above or below the submarine, leaving it unscathed. Worse, the charges were dropped from the stern or sides of the vessel. By the time the explosives hit the water, the attacking ship had already passed over the submarine’s previous location, creating a so-called “blind period.” Submarine commanders, trained to exploit this, would execute sharp turns, adjust depth, or cut engines entirely, leaving the attacking forces to explode charges in empty water.

The psychological toll was equally significant. Even when depth charges missed entirely, the crew of an escort vessel heard the deafening underwater blasts and felt the vibration reverberate through the hull. These signs of failure were interpreted as partial success, a comforting illusion that a U-boat had been damaged or deterred. In reality, many submarines survived multiple depth charge attacks. U-427, operating off Norway in April 1945, endured 678 depth charges across several hours and returned to port virtually unharmed. By 1943, British statisticians had calculated the grim reality: for every eighty depth charge attacks, only one resulted in a confirmed kill. The ratio was 60 to 1 against. Allied shipyards were building merchant vessels faster than U-boats could destroy them, but only just barely, and the margin of survival for the submariners remained perilously high.

Into this precarious balance came the hedgehog, a weapon that changed the calculus entirely. Its deployment meant that U-boat crews now faced a threat they could neither hear approaching nor evade with traditional maneuvers. No longer could a commander rely on a sudden change in depth or course to slip away during the blind period. No longer could the explosion’s roar offer false reassurance to their pursuers. Instead, the projectiles flew in a precise pattern, and if they touched the submarine’s hull, detonation was instantaneous, leaving no time to respond, no margin for error. To German submariners, it was as if the very sea itself had turned against them.

The morning on U-55 exemplified this new reality. Meyer and his crew, experienced and disciplined, had been trained for hours in evasive maneuvers, in interpreting the sounds of their surroundings, in reading every vibration and echo for hidden danger. Yet when the hedgehog struck, all their experience became almost irrelevant. The scraping noise they heard before the silent detonation marked the beginning of a new era in undersea warfare. Suddenly, the invisible predator had become an inescapable executioner. The fear it inspired was not merely tactical; it was existential. In a theater of war that had long tested nerves and endurance, the hedgehog introduced a new kind of terror: the certainty that even silence could herald destruction.

By mid-1943, the results were undeniable. Hedgehog-equipped escort ships had begun to drastically alter the effectiveness of anti-submarine operations. The weapon’s success was measured not in luck or morale, but in tangible results: submarines destroyed, wolf packs broken, and shipping lanes made significantly safer. Unlike depth charges, which could mislead both attackers and strategists, hedgehogs offered immediate feedback. Either the submarine was hit, or it escaped untouched—but its survival was no longer a certainty, and its commander could no longer rely on the blind period as a shield. The psychological and strategic impact rippled through the German naval forces. Crews who had once moved with confident precision now faced every encounter with a gnawing, unpredictable fear. The ocean that had once been their ally was now a trap, invisible yet inescapable, and the Allies were slowly turning the tide in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The stakes could not have been higher. The survival of Britain, the flow of troops and materiel to the front, and the very outcome of the war depended on controlling the Atlantic. Hedgehogs were not a flashy weapon, but their quiet, precise lethality addressed the critical flaws of depth charges in ways that transformed naval strategy. Every launch, every detonation, every U-boat sunk contributed to a new reality in which Allied forces no longer merely hoped to survive encounters—they could impose calculated, overwhelming force beneath the waves.

And yet, in those early days, the crews who faced the hedgehog had no time to reflect on its mechanics or origins. All they knew was the strange, terrifying silence that preceded death, the sudden violence that offered no warning, no roar, no mercy. For men like Meyer aboard U-55, June 4th, 1944, became a day marked not by the vastness of the Atlantic or the routine of patrols, but by an almost supernatural terror—the knowledge that an unassuming name, the hedgehog, could claim lives with a precision and certainty they had never before encountered. It was a weapon that would redefine anti-submarine warfare, a turning point in the struggle for control of the Atlantic, and a moment that would haunt the memory of every German submariner who survived to tell the tale.

The margin for error had vanished, the balance of power shifted, and the war beneath the waves would never be the same. The hedgehog had arrived, and the ocean, long a place of cunning and stealth, had become an arena of lethal inevitability. The men aboard U-55—and every U-boat that followed—would soon learn that the quietest weapon could be the deadliest, and the cost of underestimating it would be absolute.

The Atlantic, relentless and gray, carried on as if unaware of the terror above and below, yet the shadow of the hedgehog loomed large, shaping the fate of submariners, escort crews, and the course of history itself.

Continue below

The morning of June 4th, 1944, 600 m west of the French coast, the control room of U55 falls silent. Oelotant Paul Meyer stands frozen at the hydrophone station, his headset pressed tight against his ears. What he hears defies everything the criggs marine told him about Allied anti-submarine weapons.

There is no explosion, no thunderous detonation that might signal a miss, just a scraping sound overhead like someone dragging metal rods across the hull. Then nothing. 3 seconds of absolute silence. The crew exchanges glances. Every man aboard knows what depth charges sound like. They roar. They shake the boat. They announce their presence whether they hit or miss. This is different. This is quiet.

And quiet they are learning means something far worse. If you’re enjoying this deep dive into the story, hit the subscribe button and let us know in the comments from where in the world you are watching from today. The weapon that terrified me and his crew that June morning had a deceptively simple name. The hedgehog.

24 spigot mortars arranged in four cradles of six projectiles each mounted on the for deck of Allied escort vessels. To understand why this weapon struck such fear into German submariners, we need to step back to early 1943 when the balance of the Battle of the Atlantic hung by a thread.

For 3 years, Germany’s U-boat had been the apex predators of the North Atlantic. From September 1939 through March 1943, they sank over 14 million tons of Allied shipping. The statistics were staggering. In June 1942 alone, U-boat sank 637,000 tons of British merchant vessels. The convoy system introduced to counter the threat helped, but did not solve the fundamental problem.

U-boat could still approach submerged, fire their torpedoes, and slip away into the depths before escorts could respond effectively. The standard anti-submarine weapon throughout this period was the depth charge, a barrel-shaped explosive device weighing between 300 and 600 lb, filled with either aml or torpex, high explosive. The principle was straightforward enough.

Escorts would detect a submarine using Azdic, the British term for sonar, then race over the contact point and roll or launch depth charges set to detonate at a predetermined depth. The concussive force of the explosion, amplified by the density of seawater, was supposed to crush the submarine’s pressure hull or at minimum cause enough damage to force it to surface. In practice, depth charges had severe limitations.

First, they detonated at a set depth regardless of whether they were anywhere near the target. This meant the attacking vessel had to estimate not only where the submarine was, but also how deep it had gone. Get the depth setting wrong by even 50 ft, and the submarine might escape entirely unharmed.

Second, and more critically, depth charges were dropped or fired from the stern and sides of the attacking ship. By the time the charges were released, the ship had already passed over the submarine’s last known position. In those crucial seconds between losing sonar contact and reaching the drop point, a skilled U-boat commander could execute sharp turns, change depth, or cut engines to throw off pursuit.

This gap in coverage became known as the blind period. During the final approach, Azdic contact would be lost as the attacking vessel closed to within 200 yards of the target. The submarine effectively vanished from detection. U-boat commanders were trained extensively on how to exploit this window. Corvette and Capitan Vera Hartenstein, commander of U 156, described the tactic in his patrol log from August 1942. Sharp course changes to starboard at maximum angle.

reduce speed to four knots. The depth charges would explode where we had been, not where we were. The third limitation was psychological as much as tactical. Even when depth charges missed their target completely, they still exploded. The sound and shock traveled for miles underwater. To the crew of an escort vessel, that explosion felt like success.

It felt like they had done damage, scared the enemy, perhaps even scored a kill. In reality, many U-boat survived hundreds of depth charge attacks. U427, operating off the coast of Norway in April 1945, endured 678 depth charges dropped against it over a period of many hours. The boat survived and returned to base.

British statisticians tracking anti-submarine operations with ruthless precision calculated the grim truth by early 1943. Out of every 80 depth charge attacks, only one resulted in a confirmed U-boat kill. The ratio was 60 to1 against. At that rate, the allies were building merchant ships faster than U-boat could sink them, but only barely.

The margin was too thin. Something had to change. The weapon that would change everything began not as a naval device at all, but as an infantry mortar concept developed between the World Wars by Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Blacker of the Royal Artillery. The spigot mortar inverted the traditional mortar design.

Instead of loading a bomb into a tube with the propellant at the base, Blacker’s system placed the propellant charge on the projectile itself. The projectile would slide down onto a fixed rod, the spigot, and when fired, the explosive charge would push against the spigot rather than against a tube wall.

This design allowed for much heavier projectiles without requiring massive reinforced tubes that would be too heavy for mobile infantry use. The Royal Navy’s Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development, an organization with the delightfully British tendency to name itself with bureaucratic understatement while developing some of the war’s most innovative killing devices, saw potential in adapting Black Spigot, Mort, for anti-submarine warfare. The core problem they needed to solve was a head throwing capability. If a

weapon could launch projectiles forward into the area where the submarine was still visible on Azdic, it would eliminate the blind period entirely. Work began in 1941. The prototype launcher was installed aboard HMS Westcot for testing. The mathematics alone took months to resolve. Lieutenant Colonel Milis Jeffris, who led the development effort, spent entire train journeys sketching calculations on empty cigarette packets. The challenge was calculating the exact recoil force the launcher would generate. Essential

information for ensuring the weapon wouldn’t tear itself off the deck or capsize smaller escort vessels. The projectile trajectory had to be precisely calibrated so that all 24 bombs would land in an elliptical pattern roughly 100 ft in diameter, giving maximum coverage of the target area.

And the fusing mechanism had to be sensitive enough to detonate on contact with a submarine hull. but robust enough not to explode prematurely when hitting the water or being disturbed by waves. By early 1942, the system was ready for production. Each hedgehog projectile measured 7.2 in in diameter and 46.5 in in length.

The warhead contained 35 lb of torpex, an explosive compound more powerful than TNT. The total weight of each projectile was 65 lb. When fired, the launcher ripple fired the projectiles in pairs, highest trajectories first, so that despite leaving the launcher at slightly different times, all 24 would strike the water and sink at roughly the same moment. This salvo pattern was critical.

It gave the submarine no advance warning, no sound of an approaching weapon, just sudden simultaneous impacts across a wide area. The sink rate of hedgehog projectiles was 23 feet pers, significantly faster than the 8 to 9 ft pers sync rate of the Mark 6 and Mark 7 depth charges used through 1943. A hedgehog projectile would reach 200 ft depth in under 10 seconds.

It would reach a U-boat’s maximum test depth of 750 ft in just over half a minute. The speed gave submarine crews almost no time to execute evasive maneuvers once the salvo entered the water. But the true innovation, the characteristic that would make the hedgehog the most feared anti-submarine weapon of the war, was the contact fuse.

Unlike depth charges, which detonated at a preset depth, whether they were near the target or not, hedgehog projectiles only exploded if they physically struck something solid. a submarine hull, a rock formation on the seafloor. Anything else, they would simply sink to the bottom and become inert. This seemingly simple design choice had profound consequences.

First, it meant that sonar conditions remained undisturbed after a miss. If the attacking escort heard no explosions, they knew immediately that they had missed. They could maintain sonar contact and make another attack run without waiting for the water to settle. The submarine remained visible. The hunt could continue uninterrupted.

Second, it meant that even a single hit was usually fatal. A 35lb Torpex charge detonating directly against the pressure hull would punch a hole 3 to 4 in in diameter through the steel. At 250 to 300 ft depth, water would enter through that hole at approximately 400 gall per minute. The flooding was effectively unstoppable.

As water poured in, atmospheric pressure inside the submarine would spike. Temperature would climb rapidly, reaching 200 to 300° within minutes. The crew would die from searing lung damage before the boat descended deep enough for the pressure hull to collapse entirely. Production of the Hedgehog began in late 1942. By early 1943, over 100 Allied escort vessels had been retrofitted with the system.

The weapon could be mounted on destroyer escorts, corvettes, frigots, any vessel with sufficient forward deck space. Installation typically required removing the forwardmost gun turret to make room for the launcher. A trade most captains were willing to make given the weapon’s promise, but promise and performance proved to be two different things.

The initial operational results were, to put it mildly, disappointing. From January through April 1943, hedgehog equipped vessels made dozens of attacks against confirmed U-boat contacts. The success rate hovered around 5%, only marginally better than depth charges. In some months, it was actually worse. Crews began to distrust the weapon.

The silent miss felt like failure in a way that the booming explosion of a depth charge did not. At least with depth charges, you felt like you had done something. With the hedgehog, a miss meant nothing but quiet and doubt. Part of the problem was technical. Heavy North Atlantic swells would wash over the launcher, soaking the electrical firing circuits. When the crew attempted to fire, they would get incomplete patterns, only half the projectiles launching.

The pattern would be disrupted, reducing coverage and giving the submarine gaps to slip through. Another issue was the learning curve. Operating the hedgehog effectively required precise coordination between the sonar operator, the helmsman, and the weapons crew.

The attacking vessel had to maintain steady speed and course during the final approach, something that went against every instinct of a captain trying to evade potential torpedo counterattack. The Royal Navy became so concerned about the low usage rates that in early 1943 a directive was issued. Captains of hedgehog equipped vessels were ordered to file reports explaining why they had not used the weapon when they had gained underwater contact. The implication was clear.

Some captains were actively avoiding using the hedgehog, preferring the familiar reliability of depth charges even with their lower kill rate. The breakthrough came not from further technical refinement but from education. The department of miscellaneous weapons development sent officers to convoy escort bases particularly the critical base at Londereerry in Northern Ireland where many Atlantic escort groups were stationed.

These officers conducted shipwide training sessions. They presented detailed case studies of successful hedgehog attacks. They explained the mathematics behind the weapons pattern. They emphasized that while a miss with the hedgehog was silent, it also meant you could immediately attack again.

Depth charge misses, by contrast, gave the submarine minutes to escape while the water settled. The training worked. By mid1943, as crews gained experience and confidence, the kill rate began to climb. By the end of the war, statistics would show that one in every five hedgehog attacks resulted in a confirmed U-boat kill. The ratio was 5.

7:1 compared to the 60 to1 ratio for depth charges. The improvement was revolutionary. In the British Royal Navy alone, hedgehog attacks accounted for 47 confirmed U-boat kills out of 268 attacks. In actual combat effectiveness, the hedgehog was more than 10 times deadlier than the weapon it supplemented.

The US Navy, which received the Hedgehog through reverse lend lease arrangements in late 1942, proved even more successful with the weapon. American destroyer escorts, optimized specifically for anti-submarine warfare, carried the Hedgehog as standard equipment.

These ships were smaller than fleet destroyers, but packed with the latest sonar systems, radar, and weapons. The combat information center, a dedicated room where all tactical information flowed and where the executive officer could coordinate attacks while the captain handled ship handling from the bridge, proved particularly effective when combined with hedgehog. The integration of advanced sonar data feeding directly to weapons targeting allowed for unprecedented accuracy.

The most dramatic demonstration of hedgehog effectiveness came in May 1944 in the Pacific theater. The destroyer escort USS England operating as part of an anti-submarine hunter killer group encountered a Japanese submarine scouting line. Over a 12-day period from May 19th to May 31st, England sank six Japanese submarines. All six kills were made using the hedgehog.

The feat was so extraordinary that Fleet Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, sent a message to the ship’s crew. There’ll always be an England in the United States Navy. For German submarine crews operating in the North Atlantic during 1943 and 1944, the Hedgehog represented a fundamental shift in the nature of undersea warfare.

For 3 years, they had been the hunters. Now increasingly, they were the hunted, and this new weapon hunting them was unlike anything they had trained to evade. The psychological training German U-boat crews received at the submarine school in Gotenhaffen painted a clear picture of Allied anti-submarine capabilities. Depth charges were predictable. You could hear them coming.

The characteristic thrashing of propellers overhead as the escort vessel accelerated for its attack run. Then the rolling splash as the charges hit the water. You had precious seconds to maneuver. Drop to maximum depth. Execute a hard turn. Cut the electric motors to silent running. Hold your breath and wait for the explosions. If they came close, the boat would shudder and groan. Light bulbs would shatter.

Cork insulation would rain down from the overhead. But if you survived the first pattern, you had time. Time for the escort to lose contact in the turbulent water. Time to slip away. This was the doctrine drilled into every submarine from their first day of training. The Atlantic was vast, the convoys were large, but the escorts were few. A skilled commander with a well-trained crew could attack, evade, and live to hunt again.

The statistics from 1940 through 1942 supported this belief. U-boat were being lost certainly, but at rates the marine considered acceptable. For every boat that failed to return, two more were commissioned. The Wolfpack tactics developed by Grand Admiral Carl Donitz were working. In March 1943, the U-boat offensive reached its apex.

82 merchant ships totaling 476,000 tons were sunk in the Atlantic alone. Allied shipping was being destroyed faster than it could be replaced. Then came May 1943. A month later, German submariners would come to call Schwoza Black May. In 31 days, 43 U-boat were lost. 18 fell to convoy escort attacks, 14 to air patrols, the rest to accidents, mines, and other causes.

The number represented more than a fifth of operational boats. It was three times the losses of any previous month, more boats than had been lost in the entire year of 1941. Among the dead was Capitan Loant Peter Donitz, 21 years old, son of the Grand Admiral, lost aboard U 954 while attacking convoy SC 130. Five U-boat attacked that convoy.

All five were sunk. Not a single merchant ship was lost. On May 24th, 1943, Admiral Dernitz made the decision that confirmed what many U-boat commanders had already realized. The battle of the Atlantic was lost. He ordered most operational U-boat to withdraw from the North Atlantic convoy routes.

In his war diary, he attributed the catastrophic losses to the superiority of enemy location instruments and the surprise from the air, which is possible because of that. The official explanation blamed improved Allied radar and long range patrol aircraft. Both were indeed factors. But for the men who survived attacks during Black May, who felt their boats shudder under weapons that made no sound until they struck, a different truth was emerging.

Oberiteant Paul Meyer, control room watch officer aboard U55, experienced his first hedgehog attack in early June 1944. His account preserved in postwar interviews captures the psychological shock of encountering this weapon. We were running submerged at 160 m when the hydrophone operator reported propeller noises. Multiple contacts approaching fast. Battle stations were called.

We prepared for a depth charge attack. What happened next was not what we expected. There was a scraping sound along the hull like someone dragging chains across the deck. Then silence. We waited for the explosions. They did not come. The captain ordered silent running.

We maintained depth and reduced speed to minimum. The propeller noises continued circling above us. Then we heard it. Three sharp explosions in rapid succession. Not the deep boom of depth charges. These were sharper, closer. One of them was very close. The boat jumped sideways like someone had kicked it. We lost trim and started going down.

The chief engineer fought to regain control. Another pattern landed. This time, two explosions. One struck the after deck right above the motorroom. We felt the impact through the hull. The lights went out. Emergency lighting came on. Someone was screaming in the motorroom. The captain ordered us deeper. We went 200 m. The propeller noises stayed with us.

They knew exactly where we were. What Mia and his crew were experiencing was the fundamental innovation of the hedgehog. The weapon eliminated the blind period that U-boat commanders had been trained to exploit. Unlike depth charges, which forced the attacking escort to pass over the submarine and lose sonar contact before releasing weapons, the hedgehog fired forward.

The escort maintained continuous sonar tracking throughout the attack. The submarine remained visible. If the first salvo missed, the escort could immediately adjust course and fire again and again and again until the contact was destroyed or lost. The contact fuse mechanism meant that submarine crews had no way to judge how close the attacks were coming until it was too late.

With depth charges, you could count the explosions. If they were far enough away, you knew you had maneuvered successfully. The quiet between depth charge patterns meant potential escape. But Hedgehog was different. Silence meant the projectiles had missed and were now lying harmless on the ocean floor. But it also meant the escort still had perfect sonar contact and was lining up the next attack.

The weapon created a psychological trap. Silence was not safe. Silence meant the hunt was still on. U 505 survived that June attack through a combination of skill and fortune. After the second hedgehog salvo struck the aft deck, causing flooding in the motor room, the chief engineer managed to restore the trim. The captain ordered maximum depth.

They descended to 280 m below their rated test depth of 230 m. The hull groaned under the pressure. Rivets began to weep water, but they went deep enough that the escort sonar lost reliable contact. After 90 minutes of creeping slowly away at two knots on electric motors, they broke free. Four men were injured from the impacts. The outer hull had multiple holes, but the pressure hull held.

They surfaced after dark and made emergency repairs sufficient to reach the French coast. Not every crew was so fortunate. On May 6th, 1943, U638 was operating in the North Atlantic as part of a Wolfpack targeting convoy ONS5. Capitan Lotant Oscar Stinger commanded a type 7 seabo with a crew of 44 men, most of them under 25 years old.

They had sailed from Breast 3 weeks earlier on their second war patrol. The first patrol had been successful. Three merchant ships sunk, two damaged. No casualties among the crew. Stouting had been decorated. The boat had been repaired and resupplied. Morale was high. The attack on ONS5 began in the early morning hours. Multiple U-boat converged on the convoy.

The escorts detected the concentration and immediately went on the offensive. HMS Sunflower, a Flowerclass Corvette equipped with one of the early hedgehog installations, gained sonar contact on a submarine attempting to close on the convoys port flank. The corvette’s commander, Lieutenant Commander James Plumber, had attended the Hedgehog training course at Londereerry. He understood the weapon’s capabilities and limitations.

He needed to maintain a steady course and speed during the final approach. He needed precise range and bearing from the sonar operator. He needed to fire at exactly the right moment when the target was within the weapon’s effective range, but before the submarine could execute evasive maneuvers. Sunflower closed on the contact at 15 knots.

At 400 yd range, Palmer ordered the hedgehog fired. 24 projectiles arked through the darkness and splashed into the Atlantic in a roughly circular pattern. They sank at 23 ft pers. U 638 was at 90 m depth attempting to go deeper. The submarine’s crew heard nothing, no warning. Just three nearly simultaneous explosions against the pressure hull.

One projectile struck forward of the control room. Another hit amid ships on the port side. The third struck the after torpedo room. The effect was catastrophic. At 90 m depth, water pressure is approximately 9 atmospheres. When a 3 to 4 in hole is punched through a pressure hull at that depth, water enters at extraordinary velocity and volume.

400 g per minute is the calculated rate. In reality, with multiple breaches and the pressure differential, the flooding was faster. The forward compartment flooded in less than 30 seconds. The men there died almost instantly, either from the initial blast or from drowning before they could even react.

The control room crew had slightly more time, perhaps 2 minutes, as water rushed in through damaged bulkhead doors that could not be fully secured against the incoming flood. The pressure inside the submarine spiked. As the U55 crewman Mer described, when water floods in at high pressure, it compresses the air inside. The temperature rises at 9 atmospheres of pressure. The temperature can reach 200° Fahrenheit or higher.

The crews lungs would sear with each breath. Breathing itself would become impossible. Stouting, realizing the boat was finished, attempted to blow ballast and surface. It was the only chance. Get to the surface and abandon ship.

give the crew a chance to survive in the water until they could be picked up, even if that meant becoming prisoners of war. But the compressed air systems had been damaged by the blasts. The ballast tanks would not blow completely. U 638 continued descending. At 160 m, the pressure hull began to buckle. At 190 m, it collapsed. The implosion was violent enough that the crew of HMS Sunflower felt the shock wave through their own hull.

It sounded, one sailor later recalled, like an enormous underwater thunderclap. All 44 men aboard U638 died within 4 minutes of the hedgehog salvo striking home. The survivors who later came back, the men from boats that managed to evade hedgehog attacks or who were pulled from the water after their boats were sunk by other means, told consistent stories about the weapon. You could not hear it coming.

You could not judge how close it was. You could not tell if you had successfully evaded until you were already dead or miraculously alive. The randomness of it, the pure chance involved was psychologically devastating. Depth charges, for all their danger, followed patterns. You could develop tactics to counter them. You could train for them. You could control to some degree your fate through skill and experience.

Hedgehog removed that illusion of control. The only way to survive was to not be detected in the first place. Once an escort had sonar contact and was close to hedgehog range, skill mattered far less than luck. If you find this story engaging, please take a moment to subscribe and enable notifications.

It helps us continue producing in-depth content like this. The scale of U-boat losses in the final two years of the war tells the statistical story that individual accounts make humans. From January 1943 through May 1945, 785 U-boat were lost. Of those, at least 47 were confirmed killed by hedgehog attacks in British service alone.

American destroyer escorts accounted for additional kills. The exact number is difficult to calculate because many attacks involved multiple weapons systems. A hedgehog attack might damage a submarine, forcing it to surface, where it would then be finished by gunfire or depth charges. But the influence of the hedgehog extended beyond direct kill statistics. The weapon forced tactical changes throughout the U-boat fleet.

German naval intelligence first became aware of the hedgehog in late 1942 when crews reported attacks by a weapon that fit no known profile. By early 1943, captured Allied documents and interrogation of rescued British sailors confirmed the weapon’s existence and basic operation. The Marine response was to accelerate development of acoustic homing torpedoes.

The T5 Zancig, called Gnat by the Allies, entered service in September 1943. The torpedo could home in on propeller noise, allowing U-boat to attack escort vessels from longer ranges without needing to use the periscope. If escorts were reluctant to close to hedgehog range, the theory went, the submarines would regain some of their tactical advantage.

In practice, the acoustic torpedoes provided only limited relief. Allied escorts quickly adapted by deploying noise-making decoys called foxes, towed devices that created false acoustic targets. More fundamentally, the introduction of escort carriers and very long range patrol aircraft by mid 1943 meant U-boat were increasingly vulnerable on the surface and during transit to and from patrol areas.

The battle of the Atlantic was not won by any single weapon or technology, but by the integration of multiple systems. Improved radar, particularly centimetric radar that U-boat radar detectors could not detect. Better sonar, more escorts, escort carriers provided air cover in the mid-Atlantic gap where land-based aircraft could not reach.

Breaking of German naval codes, allowing convoys to be routed away from known U-boat patrol lines. And yes, a head throwing weapons like the hedgehog that fundamentally changed the tactical calculus of undersea warfare. But for the men serving in U-boat, the hedgehog became a symbol of how completely the tide had turned.

It represented the moment when they stopped being hunters and became prey. The casualty statistics reflect this transformation. Of the approximately 40,000 men who served in the U-boat service during World War II, nearly 30,000 died in action, a casualty rate of 75%, the highest of any branch of any nation’s military in the entire war.

By 1944, U-boat crewmen knew they were statistically unlikely to survive the war. Yet they continued to sail, some from duty, some from ideology, some because refusal meant execution for cowardice. And some, perhaps, because once you have survived your first patrol, the idea of surviving the next does not seem impossible, even when statistics say otherwise.

The last U-boat sunk by hedgehog fire was U881, destroyed on May 6th, 1945, 2 days before Germany’s surrender. The attack took place off the coast of Rhode Island, one of several U-boat that continued operating even after Hitler’s death and the collapse of the Nazi regime. Destroyer escorts USS Athetherton and USS Mobley gained sonar contact on the submerged submarine and pursued the contact for 7 hours, making multiple hedgehog attacks.

The final salvo struck U81 at a depth of 100 ft. There were no survivors from the crew of 48. When the war in Europe officially ended on May 8th, 156 U-boat surrendered to Allied forces. Another 222 were scuttled by their crews rather than be handed over. The boats that surrendered were taken to various ports and examined in detail.

Allied technical intelligence teams photographed and documented everything. The acoustic torpedoes, the snorkel systems, the advanced type XXI submarines that had only begun entering service in the final months of the war. They also interviewed the surviving crewmen. These interviews, conducted while memories were fresh and before official German naval histories could establish collective narratives, provide some of the most detailed accounts of what it was like to serve in a U-boat during the period when hedgehog and similar weapons dominated anti-submarine

warfare. Hansville Helm Coppen, a machinist’s mate who served on three different boats from 1943 to 1945, described the evolution of crew attitudes. In the beginning, you believed you could outsmart the escorts. You have been trained. You knew the procedures. Go deep. Change course. Silent running. Wait them out.

By 1944, we knew that training meant very little. If an escort had contact and got close enough, you were probably going to die. It became not about skill, but about avoiding detection in the first place. We spent more and more time submerged. We used the snorkel to avoid surfacing. We avoided convoys when possible.

We had become, how do you say, hunted animals. This shift from hunter to hunted represents the true psychological cost of weapons like the hedgehog. It was not just that the weapon was effective at sinking submarines. It was that it removed the agency from submarine crews. their training, their experience, their courage. These things still mattered, but they no longer determined survival.

The cold mathematics of sonar range, projectile distribution patterns, and explosive yield determined who lived and who died. In that sense, the hedgehog was a weapon of the industrial age in its purest form. Individual human qualities became subordinate to mass production and technical advantage. The Allies could build more escorts.

They could equip those escorts with better sensors and weapons. They could train more crews. The arithmetic was simple and brutal. Germany could not match Allied industrial output. Therefore, German submariners would die in increasing numbers until there were no more submarines or no more submariners or the war ended. Whichever came first, the war ended first.

On May 8th, 1945, at 11 p.m. all hostilities ceased in Europe. U-boat at sea received orders to surface, fly black flags of surrender, and proceed to designated Allied ports. Some complied immediately. Others took days to receive the orders or to accept their reality. A handful, operating in distant waters, continued brief patrols before finally giving up.

The U-boat war which had begun on September 3rd 1939 with U29 sinking the armed merchant cruiser HMS Raal Pindi ended with hundreds of submarines limping into Allied ports carrying exhausted crews who had somehow survived when 75% of their comrades had not. The hedgehog remained in service long after the U-boat it was designed to destroy were gone.

The US Navy continued using the system through the Cold War, not retiring it until the late 1980s. The Soviet Union developed their own version, the MBU2000, which evolved into the MBU60. The principle of a head-throwing anti-submarine mortars influenced the design of rocket launched anti-submarine weapons that remain in use today.

But the original hedgehog, that crude assembly of spigot mortars that looked like nothing so much as a bristling hedgehog when mounted on a ship’s forcel, that weapon is remembered primarily for what it did during three years of war in the Atlantic. It helped sink U-boat, not by dozens or hundreds in any single dramatic battle, but one at a time in cold waters far from shore, in attacks that lasted minutes and left no survivors to tell what happened.

The kills accumulated, the statistics shifted, and eventually the hunters became the hunted. The story of the hedgehog and the German submariners it destroyed is ultimately a story about technological competition in warfare. It is about how innovation in weapons development can shift strategic balance. But it is also a story about human beings caught in circumstances beyond their control trying to survive in machines that could become their coffins in seconds. Oberiteant Paul Meer survived the war.

U5 was captured intact on June 4th, 1944. The same day Meer experienced his first hedgehog attack. The boat was boarded by US Navy personnel before it could be scuttled. Mia and most of his crew became prisoners of war. After the war, Mia returned to Germany and worked as a marine engineer. He rarely spoke about his service in U-boat.

When he did, he described it as a matter of fact, without drama or embellishment. We did our duty. Many died. I was fortunate. That was all. That fortune or misfortune, depending on perspective, that determined who died and who survived in the U-boat service of World War II was increasingly influenced by weapons like the hedgehog.

Not because the weapon was perfect. It was not. Not because it alone turned the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic. It did not. but because it represented a fundamental shift in the nature of anti-submarine warfare, removing the blind period that had allowed U-boat to survive for so long. In that narrow technical innovation lay the difference between life and death for thousands of men on both sides, the escorts who no longer had to pass over their targets before attacking, the submariners who no longer had those precious seconds to evade. The

mathematics of war expressed in spigot mortars and contact fuses and salvos of projectiles arcing through the air to splash into dark water above men who could not hear them coming until it was already too late.

News

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came…

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came… …

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I…

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I… At…

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…”

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…” I didn’t expect the…

My Dad Shredded My Harvard Acceptance Letter. “Girls Don’t Need Degrees, They Need Husbands,” He Spat – I Didn’t Cry. I Made A Call

My Dad Shredded My Harvard Acceptance Letter. “Girls Don’t Need Degrees, They Need Husbands,” He Spat – I Didn’t Cry….

At 13, My Dad Beat Me And Threw Me Out Into A Raging Blizzard After Believing My Brother’s Lies. I Crashed At My Friend’s Place Until…

At 13, My Dad Beat Me And Threw Me Out Into A Raging Blizzard After Believing My Brother’s Lies. I…

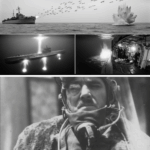

CH2 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire At dawn on March…

End of content

No more pages to load