German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

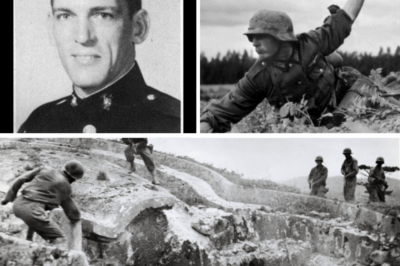

The sky over Tunisia was pale blue and brittle with cold, the kind of air that made engines breathe sharper and men feel alive. On the morning of November 23, 1942, Oberleutnant Hans-Joachim Marles, a twenty-five-year-old veteran of more than seventy combat missions, guided his Messerschmitt Bf 109 through the thin air over the desert. Below, the Sahara stretched endlessly, rippling gold and white under the sun. To the west, faint dust clouds marked the chaos of battle as Rommel’s Afrika Korps fought to stem the Allied advance.

Marles adjusted his oxygen mask and glanced at his wingman flying tight on his right. They had been hunting bombers for an hour, weaving through columns of warm air rising from the desert. Every so often, he tapped the rudder pedal, keeping the formation tight. There was no sign of the enemy. Then his radio crackled—static first, then a clipped voice from ground control. “Achtung! Unknown aircraft approaching from the west. Twin engines. Altitude twenty thousand feet.”

Marles frowned. Twin engines? The British didn’t fly twin-engine fighters in this theater. That meant Americans—probably P-39s or maybe the new P-40 variant. Nothing to worry about. The Messerschmitt could outclimb, outturn, and outrun anything the Americans had so far sent into the air.

He scanned the horizon, and then he saw it—just a glint at first, like a flash of metal in the sun. Then it resolved into shape. Long wings. Twin tail booms. Two propellers spinning in opposite directions. It didn’t look like anything he’d seen before.

The stranger climbed fast, impossibly fast for something that large. Marles pushed his throttle forward, the supercharger whining, his engine straining against the thin air as his Bf 109 clawed for altitude. He banked left, rolling into a climbing turn to get position above the enemy fighter. That was where the Messerschmitt always had the advantage. Altitude meant life.

But this time, the American stayed with him.

Marles felt his pulse quicken. No fighter that heavy should be able to match a 109 in the climb, yet the twin-boomed machine mirrored every movement, its silver fuselage gleaming in the sunlight. He pushed his throttle to the stop. The Messerschmitt vibrated, the airspeed needle trembling. The American climbed smoothly past him, its twin engines pulling it like a predator built for the sky.

He broke off, diving toward the desert floor. It was a maneuver that had saved him dozens of times before. No Allied fighter could follow a 109 in a steep dive without losing control or tearing its wings off. He dropped fast, the altimeter spinning down, wind screaming against the canopy.

But when he leveled out and glanced back, his stomach dropped. The American was still there.

Two engines. Two tails. Four machine guns and a cannon mounted in the nose. It was closing fast.

Marles rolled hard left, then right, jinking through the air, trying to throw off the pursuit. His breath came in short bursts. He pulled into a sharp climb, g-forces pressing him into his seat until his vision narrowed to a tunnel of gray. The American followed him into the clouds. For a full minute, Marles danced with his unseen enemy, then punched through the top of the cloud bank, gasping in the sunlight. The sky was empty.

When he landed hours later at his base near Tripoli, his hands were still trembling. The mechanics swarmed his Messerschmitt, checking for bullet holes, but found none. There was no physical damage. Yet something inside him had cracked that morning—something that had been unshakable since 1939.

The belief that the Luftwaffe’s fighters were untouchable.

The strange American machine that had stalked him through the clouds was the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. It was about to change everything German pilots thought they knew about air combat.

Two years earlier, the Luftwaffe had ruled the sky. In 1940, when the first Messerschmitt Bf 109Es screamed over France and the English Channel, they were unmatched in speed, climb, and firepower. They had been built for conquest, and they delivered it. In Spain, Poland, France, and the Low Countries, German pilots had learned their craft in blood. By the time the war reached North Africa, the Luftwaffe was the most experienced and confident air force in the world.

Its doctrine was simple but devastatingly effective. Pilots flew in pairs—Rotten, they called them. Two Rotten made a Schwarm—a flexible, four-plane formation designed to dominate the sky. The British and Americans still clung to rigid V-shaped groups that limited visibility and response time. The Germans had replaced formation pride with survival instinct. The Schwarm could break, scatter, and reform in seconds, turning the sky into a chessboard of deadly opportunity.

Their strategy relied on speed, altitude, and precision. They didn’t waste time dogfighting. They hunted from above, diving on their targets in short, lethal bursts, then climbing away before the enemy could react. Each engagement was a matter of seconds—attack, disengage, disappear.

It worked because the Messerschmitt was fast enough to make it work.

The Bf 109, the pride of German engineering, was more than just a fighter; it was a symbol. First flown in 1935, it had evolved continuously through the war, each model more refined, more lethal than the last. By 1942, the F and G variants represented the pinnacle of that lineage. Streamlined fuselages, lightweight frames, and the powerful Daimler-Benz 601 and 605 engines gave them unmatched agility.

A fully loaded 109 weighed just under 7,000 pounds and could reach 390 miles per hour at altitude. Its armament—a 20mm cannon firing through the propeller hub and twin machine guns above the engine—was enough to shred a bomber or snap the wings off an enemy fighter in seconds.

German pilots loved their machines with an almost personal devotion. They knew every sound, every vibration. They could tell by feel when their engine was running too rich, when the air density was thinning, when the climb rate began to falter. They also knew the aircraft’s flaws—the narrow landing gear that made takeoffs and landings treacherous, the limited visibility from the cockpit, and the tendency to compress in high-speed dives. But in the hands of a skilled pilot, none of it mattered.

Until now.

In 1942, the Luftwaffe faced a new kind of war. The British had recovered from the Battle of Britain. The Americans had arrived, bringing with them industry, manpower, and an optimism that unnerved German veterans. The Allies were learning fast. But in the minds of men like Marles, the outcome was already decided.

No foreign fighter could match a 109 in speed, climb, or agility. The P-40 Warhawk? Too slow. The P-39 Airacobra? A curiosity, with its engine mounted behind the pilot and its power fading above 15,000 feet. Even the vaunted Spitfire, that darling of British propaganda, was hampered by its range. It could dogfight well enough near its own bases, but it couldn’t stay airborne long enough to escort bombers into German-held territory.

That limitation was everything.

German pilots exploited it mercilessly. They would watch from altitude, tracking the Spitfires as they reached their turning point and headed home, leaving bombers naked in the sky. Then the 109s would fall upon the defenseless formations, turning them into burning metal that rained over the Channel.

For years, it was a perfect system. The Luftwaffe dictated the terms of combat.

Then came the P-38.

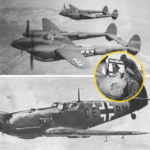

The first time German pilots saw it, they laughed. It looked ungainly—two engines, twin tails, and a cockpit perched between them like an insect’s thorax. No single-plane design had ever looked less like a thoroughbred fighter. But the laughter stopped quickly.

The P-38 was fast—astonishingly fast. Its twin Allison V-1710 engines drove counter-rotating propellers, eliminating the torque problems that plagued single-engine aircraft. It climbed like a homesick angel, handled high altitudes with ease, and could stay in the air longer than any German fighter. Even more terrifying for the men who faced it, the Lightning carried all its weapons—four .50 caliber machine guns and a 20mm cannon—in the nose, giving it unmatched accuracy.

In a head-on pass, there was no convergence to worry about, no spread of fire. Every round went straight where the pilot aimed.

And that was what Marles had seen that morning over Tunisia—a fighter that broke every rule he had learned. A machine heavier than his Messerschmitt but faster in the climb, steadier in the dive, deadlier in the pursuit.

When he sat down that night in the mess hall, surrounded by the laughter and cigarette smoke of men still believing in their own superiority, he said nothing about what he had seen. He poured himself a drink, stared into it for a long time, and wondered whether the age of the 109 was ending.

Outside, the desert wind howled against the hangars. And somewhere across the dunes, in an airfield newly built by the Americans, the twin engines of another P-38 Lightning roared to life.

Continue below

In the cold morning air over Tunisia on November 23rd, 1942, Oberite Hans Yoim Marles’s wingman watched something that should not have been possible. An American fighter with two engines and twin tail booms had just matched their Meshaches BF- 109 in a climbing turn.

The German pilot pushed his throttle to the stops, feeling his supercharger strain as the air thinned above 20,000 ft. The strange twin-tailed machine stayed with him. Then it began to pull ahead. He broke left, diving hard toward the desert floor, expecting the heavier American aircraft to fall behind. Instead, it followed him down, closing the distance with each passing second.

When he pulled out of the dive and looked back, the American was still there. Twin propellers spinning in opposite directions, nose guns pointed directly at his tail. He rolled hard, pulled into a desperate climb and barely escaped into a cloud bank. When he landed at his base near Tripoli, his hands were still shaking. The mechanics found no damage to his aircraft. But something else had been damaged that morning.

It was the assumption that had carried the Luftwuffer through 3 years of war. The belief that German fighters were faster, better, and always one step ahead of whatever the Allies could produce. The twin boom fighter he had faced was called the Loheed P38 Lightning, and it was about to change everything German pilots thought they knew about air combat.

If you’re enjoying this deep dive into the story, hit the subscribe button and let us know in the comments from where in the world you are watching from today. The Luftvafer entered the North African campaign in 1940 as the most experienced and tactically advanced air force in the world. Their pilots had honed their skills in Spain during the Civil War from 1936 to 1939. They had swept through Poland in weeks, dominated the skies over France, and fought the Royal Air Force to a standstill during the Battle of Britain.

By the time American forces arrived in North Africa in late 1942, German fighter pilots operated with the confidence of men who had never met their equals. Their primary fighter, the Messmitt BF-1009, had been in continuous production since 1937. By 1942, the latest variants, the BF-1009F, and the newer G models, represented the peak of German engineering refinement.

The BF-1004 carried a single 20 mm cannon firing through the propeller hub and two 7.92 mm machine guns mounted above the engine. It weighed just under 7,000 lb fully loaded and could reach speeds of 390 mph at altitude. Its Daimler Benz 600 series engine equipped with a mechanically driven supercharger gave it excellent performance between 15,000 and 20,000 ft. German pilots knew this aircraft intimately.

They understood its strengths and its limitations. They knew that above 25,000 ft the engine began to lose power. They knew the thin wings gave excellent maneuverability but made the aircraft unstable in high-speed dives. They knew the narrow landing gear made ground handling dangerous. But they also knew that in the hands of a skilled pilot, the 109 could outclimb, outturn, and generally outfight anything the British or Americans had put in the air up to that point.

The tactical doctrine built around the BF-1009 reflected years of combat experience. Luftvafa fighter pilots operated in pairs called rotten. Two Rotten made up a swarm, a flexible four-plane formation that allowed mutual support while maintaining individual freedom of action. This was fundamentally different from the rigid three-plane V formations that British and early American units still used.

The German approach emphasized altitude advantage, speed, and decisive attacks. Fighter units would climb high above bomber formations, dive through them at maximum speed, fire a short burst, and then climb back up using their momentum. This hit and run tactic, refined over years of combat, minimized the time spent in the vulnerable turning fight, where numbers could overwhelm skill.

It worked because German fighters were almost always faster in the dive and better in the climb than their opponents. The Supermarine Spitfire, the best fighter the Royal Air Force had in 1942, could match the BF-1009 in a turning fight and was slightly faster at lower altitudes. But it lacked range.

Spitfires could barely escort bombers 100 miles from their bases before having to turn back. This gave German pilots a predictable window, wait for the escorts to leave, then attack the bombers. The early American fighters sent to North Africa in 1942 were even less threatening. The Curtis P40 Warhawk was slower than the BF-1009 at all altitudes and couldn’t climb with it.

The Bell P39 era Cobra with its mid-mounted engine and tricycle landing gear, had poor high altitude performance due to the lack of an effective supercharger. German pilots learned to simply climb above these American fighters and attack from positions where the Americans couldn’t respond effectively.

This technical superiority was reinforced by psychological factors. Luftvafa pilots in North Africa were veterans. Many had more than 100 combat missions. Some had been fighting since 1939. They had seen the Allies throw aircraft after aircraft into the sky, and they had shot them down in numbers that seemed to prove German dominance was a matter of natural superiority, not just temporary advantage.

The younger pilots arriving as replacements heard stories from the veterans. Stories of easy victories over lumbering British bombers and outclassed French fighters. stories of the brief, sharp engagements where speed and altitude decided everything before the enemy even knew the fight had started. This created a culture of confidence that bordered on arrogance. German fighter pilots expected to win.

They expected Allied pilots to be poorly trained and their aircraft to be inferior. When they encountered something that didn’t fit this pattern, the psychological impact was profound. The American entry into the North African air war began in November 1942 with Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French Morocco and Algeria. The initial American fighter presence was limited.

P40 Warhawk units provided closeair support and flew defensive patrols, but they were clearly outmatched in air-to-air combat against the BF-1009. American commanders knew they needed better aircraft. They needed fighters that could escort bombers deep into enemy territory.

They needed fighters that could match German performance at altitude. They needed something that could change the dynamic of air combat over the Mediterranean. The P38 Lightning was designed to meet requirements that seemed almost contradictory. In 1937, the United States Army Air Corps issued a specification for a high altitude interceptor capable of reaching 20,000 ft in 6 minutes and achieving a top speed of at least 360 mph.

No single engine design could meet these requirements with the engines available at the time. Lockheed’s lead engineer, Clarence Kelly Johnson, chose an unconventional solution. He would use two engines, but instead of mounting them on a conventional fuselage, he placed each engine in a separate boom extending back from the wing.

The pilot sat in a central necessel between the booms. The tail surfaces connected the two booms at the rear. This gave the aircraft its distinctive appearance and solved several engineering problems simultaneously. Each boom contained an Allison V171012 cylinder liquid cooled engine. These engines, producing over a,000 horsepower each, drove three-bladed propellers that rotated in opposite directions.

This counterrotating configuration eliminated the torque effect that made single engine fighters difficult to control during takeoff and hard maneuvering. More importantly, each engine was equipped with a general electric turbo supercharger. This was the key to the Lightning’s high altitude performance.

Most fighters in 1942 used mechanically driven superchargers that were geared directly to the engine. These worked well at their designed altitude, but lost efficiency above or below that point. The BF-1009 supercharger, for example, was optimized for around 18,000 ft. Above that altitude, the engine rapidly lost power. The P38’s turbo supercharger was different.

It used exhaust gases to spin a turbine that compressed incoming air before it entered the engine. This system automatically adjusted to altitude, maintaining manifold pressure and engine power well above 25,000 ft. At 30,000 ft, where a BF-1009 was gasping for air and barely able to maintain 200 mph, a P38 could still cruise at over 300 mph and had power reserves for combat maneuvering. The Lightning’s armament was concentrated in the nose of the central nel.

One Hispano 20 mm cannon and four Browning 50 caliber machine guns, all mounted in a tight cluster, fired straight ahead. There was no need to calculate convergence angles or worry about harmonization at different ranges. Where the nose pointed, the bullets went. This made gunnery simpler and more effective, especially at long range.

A 2- second burst from all five guns delivered over 20 lb of projectiles. The cannon shells were particularly devastating. A single 20 mm high explosive round could tear through aluminum skin, sever control cables, and destroy critical components. Against the relatively lightly built fighters of the era, a handful of hits was often enough to bring an aircraft down.

The Lightning’s size and weight were both advantages and limitations. At over 17,000 lbs loaded, it was more than twice the weight of a BF-1009. This made it less maneuverable in the classic turning dog fight. A 109 pilot who could force a lightning into a slow speed, tight radius turning fight had the advantage.

But the P38’s weight also gave it tremendous energy retention. In a dive, it accelerated rapidly and could reach speeds that would tear the wings off lighter fighters. Its thick wing, designed for high altitude flight, was incredibly strong. In high-speed dives, where BF-1009 had to pull out carefully to avoid overstressing the airframe, Lightning pilots could pull harder and earlier, using their speed to zoom back up to altitude. The twin engine configuration provided redundancy.

If one engine was hit, the other could often bring the pilot home. This was psychologically important. Singleenine fighter pilots knew that any serious engine damage meant bailing out or crash landing. Lightning pilots had a better chance of survival even after taking battle damage. This knowledge affected how aggressively pilots were willing to fight.

The first P38 units arrived in North Africa in November and December of 1942. They were assigned to the 12th Air Force operating from primitive air strips in Algeria and Tunisia. The pilots were mostly inexperienced. Many had fewer than 300 hours of total flying time and no combat experience whatsoever.

They had trained in the United States on tactics that were already outdated, flying tight formations that sacrificed situational awareness for visual cohesion. They had been taught to respect Luftvafer’s reputation. Their instructors, some of whom were British pilots with combat experience, had told them that German pilots were skilled, aggressive, and flying superior aircraft. The young Americans arriving in North Africa believed they were about to face an enemy that was better than them in almost every measurable way.

The Lightnings themselves arrived in various states of readiness. Some had been flown across the Atlantic via the southern ferry route, island hopping from Florida to Brazil to West Africa and then north to the combat zone. Others arrived by ship, created and required assembly. The aircraft suffered from teething problems. The complex turbo supercharger system sometimes failed. Intercooler leaks were common.

The engines, sensitive to the fine sand that hung in the North African air, required constant maintenance. Pilots reported cockpit heating problems. At high altitude, where temperatures dropped to 40 below zero, the heaters couldn’t keep up. Some pilots flew missions in electrically heated suits borrowed from bomber crews.

Others simply endured the cold, their hands so numb they struggled with the controls. Despite these problems, the P38 had capabilities that were immediately apparent. During initial familiarization flights, pilots discovered they could climb to 20,000 ft faster than any fighter they had previously flown.

They found that the aircraft was stable and easy to fly on instruments, important for the long overwater flights and bad weather operations common in the Mediterranean. And they discovered that in a straight line, nothing could catch them. Ground crews worked around the clock to keep the lightnings operational.

Mechanics learned to seal engine cowlings against sand infiltration. They improvised dust filters for the turbo superchargers. They learned to preheat engines in the cold desert nights to prevent damage during startup. The maintenance demands were heavy.

Each Lightning required more man-h hours per flight hour than a single engine fighter. But the aircraft that were mission ready demonstrated performance that began to change the calculation of air superiority over North Africa. The first combat mission came on December 5th, 1942. A flight of four P38s was tasked with escorting a formation of Martin B26 Marauder medium bombers attacking a German supply depot near Tunis.

The Lightning pilots climbed to 22,000 ft, positioning themselves above and behind the bombers. The formation crossed into enemy- held territory. The pilots scanned the sky, watching for the dark specks that would indicate approaching fighters. German radar stations along the coast had tracked the incoming raid. Luftvafa controllers scrambled two Staflon of BF-1009s from airfields near Bizert.

12 German fighters climbed hard to intercept. The German pilots had been briefed that American escort fighters would likely be P40 Warhawks, which they knew well and did not fear. As they approached 30,000 ft, they spotted the bomber formation below them, and they saw the escorts, but the escorts looked wrong. They had twin booms and twin engines.

Some of the German pilots thought they were looking at a new type of twin engine bomber, or perhaps a reconnaissance aircraft. The Stafle leader ordered his pilots to ignore the strange aircraft and focus on the bombers. He rolled into a dive, building speed, planning to make a single high-speed pass through the bomber formation before climbing back to safety. The Lightning pilots saw the German fighters diving.

The flight leader, a first lieutenant from California with less than 400 hours of total flying time, made a split-second decision. Instead of staying in a defensive position above the bombers, he pushed his throttles forward and dove to intercept the German fighters. His wingman followed. The other two Lightnings stayed with the bombers.

The closing speed was tremendous. The BF1009s were diving at well over 400 mph. The Lightnings were accelerating in their own dive. The German leader lined up on the lead bomber, his finger tightening on the trigger. Then tracer rounds flashed past his canopy. He jerked the stick, breaking off his attack.

The strange twin engine fighter was shooting at him, and it was keeping up with him in the dive. He pulled hard, trading speed for altitude, expecting the heavier American aircraft to overshoot. It didn’t. The Lightning pulled with him, its powerful engines maintaining energy through the climbing turn. He rolled and dove again. A defensive maneuver designed to force any pursuer into an overshoot. The lightning stayed glued to his tail. He could see it in his mirror now.

Both propellers spinning, nose guns flashing. Rounds walked up toward his aircraft. He jettisoned his bellyrop tank, threw the stick hard over, and dove for the deck. At 500 ft above the desert, he leveled out and firewalled his throttle, running for home. The lightning followed him for 30 mi before breaking off.

Its pilot unwilling to follow too deep into enemy territory on his first combat mission. The rest of the engagement was equally shocking for the Germans. The other Lightning pilot engaged two BF-1009s that were climbing back to altitude after their first pass. He dove on them from above, exactly the tactic the Germans usually employed. The German pilots broke in opposite directions.

He followed one of them, settling into a firing position with ease. The German pilot tried every evasive maneuver in his repertoire. Hard turns, rolling scissors, vertical reversals. The Lightning, while not matching him turn for turn, used its superior speed and energy retention to stay in the fight.

When the German pilot tried to climb away, the Lightning climbed with him, its turbo superchargers maintaining full power, while the BF-100 9’s engine gasped in the thin air. The German pilot leveled out at 28,000 ft, hoping to find sanctuary in the altitude where Allied fighters usually lost performance. The Lightning was still with him, still closing. He pushed over into a desperate split s diving inverted and pulling through to reverse course.

The lightning followed through the maneuver, absorbing gravitational forces that should have made the pilot black out. When the German pulled out, heading east at full throttle, the American was 400 yd behind him and closing. A burst of 50 caliber fire and 20 mm cannon shells tore through the BF-1009’s tail section. The German aircraft snap rolled and went into an uncontrolled spin.

The pilot bailed out at 8,000 ft, landing in the desert near a German outpost. He was picked up within hours. That evening, he gave his debrief to intelligence officers. He described an American twin engine fighter that could match the BF-1009 in a dive, outclimb it at altitude, and stay with it through multiple defensive maneuvers. The intelligence officers were skeptical.

Twin engine fighters were heavy and slow. Everyone knew this, but the pilot insisted, and his story matched reports coming in from other units that had encountered the strange American aircraft that day. The engagement near Tunis was not an isolated incident. Over the following weeks, P38 units flew more escort missions and began ranging ahead of bomber formations on fighter sweeps. German pilots continued to encounter them and the pattern repeated.

The lightning was fast. They were especially fast above 20,000 ft. They could dive with any German fighter and often pull away and their concentrated nose armorament was devastating when it connected. Luftvafa intelligence scrambled to understand what they were facing. Captured documents and interrogations of downed American pilots provided some technical details, but the full picture remained unclear for several weeks.

What was clear was that American pilots flying these aircraft were becoming increasingly aggressive. Initial caution gave way to confidence. The Americans had arrived expecting to be outmatched. Instead, they found themselves flying an aircraft that could compete on equal terms with the best the Luftvafer had. This psychological reversal happened quickly.

Within three weeks of the first combat missions, American Lightning pilots were actively hunting German fighters rather than simply defending bombers. They used the altitude advantage their turbo superchargers provided to position themselves above German formations. They initiated combat on their own terms, diving on enemy aircraft and then climbing away before the Germans could organize a coordinated response.

The tactics were crude at first, but they worked. By early January 1943, P38 units were claiming multiple victories in almost every engagement. The German response evolved in stages. Initial confusion gave way to respect, then to tactical adaptation. Luftvafer pilots were ordered to avoid prolonged combat with the lightning at high altitude.

They were instructed to use their superior turning ability at lower altitudes and slower speeds to negate the American advantages. If engaged by a lightning above 20,000 ft, the recommended tactic was to dive away and separate rather than attempting to outclimb or outrun the American fighter. These were sound tactical instructions, but they represented a fundamental shift in German doctrine.

For three years, Luftvafa fighters had dictated the terms of engagement. They chose when to fight and when to disengage. Now they were being forced into a reactive posture. Some German pilots referred to the P-38 as Deg Gabulvance TOEFL, the forktailed devil. The nickname spread through Luftvafer squadrons. It carried a mixture of respect and apprehension.

This was not the usual contemptuous nickname given to inferior enemy equipment. This was acknowledgment that the Americans had fielded a weapon that changed the balance of power in the air. If you find this story engaging, please take a moment to subscribe and enable notifications. It helps us continue producing in-depth content like this.

By February 1943, the P38 had become a significant factor in the North African Air War. American bomber formations now penetrated deeper into enemy territory with less attrition. German airfields and supply lines came under more frequent attack. Luftvafer units already stretched thin across multiple fronts found themselves losing aircraft and pilots at rates they could not sustain.

The material reality behind these tactical shifts was stark. Germany was fighting a multiffront war. The Eastern Front consumed enormous resources. By early 1943, the disaster at Stalingrad was unfolding. The Luftvafa had lost hundreds of transport aircraft trying to supply the encircled Sixth Army.

Fighter units in Russia were fighting desperately to maintain local air superiority against growing numbers of Soviet aircraft. In the west, the Allied bombing campaign against Germany itself was intensifying. Luftvafa fighter units were being pulled back to defend the Reich. This meant fewer aircraft and less experienced pilots available for the Mediterranean theater.

Every BF-1009 lost over Tunisia was an aircraft that couldn’t defend Germany. Every experienced pilot killed or captured represented years of training that could not be replaced. The P38 contributed to this attrition in ways beyond simple kill ratios. Its range allowed it to attack German airfields, destroying aircraft on the ground before they could take off.

Its speed made it difficult to intercept. Its durability meant pilots could return from missions that would have been fatal in single engine aircraft. The cumulative effect was erosion of German air power at a critical moment in the war. American production provided the quantitative backdrop to this qualitative shift.

Loheed’s Burbank factory was producing P38s at an increasing rate. By mid 1943, the factory was delivering over a 100 aircraft per month. These numbers were small compared to the massive production runs of P47s and P-51s that would come later, but in early 1943, the P38 represented the cutting edge of American fighter technology in the Mediterranean theater. More aircraft meant more units could be equipped.

More units meant more missions. More missions meant constant pressure on German forces. The Luftvafer could not match this production rate. German industry was producing BF-1009s in large numbers, but those aircraft were needed everywhere. The Mediterranean was becoming a secondary theater for German planners.

Resources flowed to Russia and to the defense of Germany. Units in North Africa received replacement aircraft and pilots when they were available, but priority went elsewhere. This meant that even when German pilots developed effective tactics against the Lightning, they often lacked the numbers to implement those tactics effectively.

A swarm of four BF-1009s might understand how to counter a P38, but if they encountered eight Lightnings, numbers negated tactical skill. The psychological impact on American pilots extended beyond simple confidence in their aircraft. They began to believe they could win the air war. This belief affected everything from individual combat decisions to strategic planning at higher levels.

Bomber crews noticed the difference. They reported seeing lightning escorts engaging German fighters far from the bomber stream, preventing attacks before they developed. They saw German fighters breaking off attacks when lightnings appeared rather than pressing through to strike the bombers.

This changed the calculus of survival. Missions that would have resulted in 50% losses without effective escort returned with minimal casualties when P38s were present. Crew morale improved. Pilots volunteered for missions they would have dreaded weeks earlier. The belief that they might survive their combat tours became a realistic expectation rather than a desperate hope. For German pilots, the opposite was true.

Veterans who had grown accustomed to air superiority now faced an opponent they could not consistently defeat. The psychological strain was immense. Combat reports from this period show increasing caution in German operations. Fighter units requested better intelligence on American fighter types before committing to attacks.

Pilots reported breaking off engagements when they identified lightnings in the area, even when they held tactical advantages. This was not cowardice. It was a realistic assessment of capability, but it represented erosion of the offensive spirit that had characterized the Luftvafer in earlier years of the war. The technical advantages the P38 enjoyed were not absolute. German pilots and engineers quickly identified its vulnerabilities.

The Lightning’s wide turning radius made it susceptible to tight turning opponents at lower altitudes. Its complex turbo supercharger system was vulnerable to battle damage. A single well-placed hit could disable the intercooler or sever the exhaust ducting, causing catastrophic engine failure.

The counterrotating propellers, while solving torque issues, created unique aerodynamic problems. If one engine failed, the asymmetric thrust was pronounced. Pilots had to quickly trim the aircraft and reduce power on the remaining engine to maintain control. In combat, with adrenaline surging and attention focused on multiple threats, this was a demanding task. Some pilots failed to manage it and lost control.

The aircraft’s size also made it an easier target to spot and track. German pilots learned to look for the distinctive twin boom silhouette. They developed tactics specifically designed to exploit lightning weaknesses.

They would attempt to force encounters at lower altitudes where their BF-1009s could turn inside the heavier American fighters. They would target single lightnings that had become separated from their formations. They would attack from below where the P38’s pilot had limited visibility due to the aircraft’s design. These tactics achieved results. P38s were shot down. Pilots were killed or captured.

The lightning was not invincible, but the critical factor was that these German counter tactics required specific conditions to work. They required getting the lightning pilot to fight on German terms. Experienced lightning pilots learned not to accept those terms. They maintained altitude. They used their speed to disengage when the tactical situation turned unfavorable.

They worked in pairs, covering each other and preventing German fighters from isolating individual aircraft. The learning curve was steep. Some American pilots, aggressive but inexperienced, dove into turning fights at low altitude and paid with their lives. Others learned from observation and from the veterans who survived the early battles. Tactics manuals were updated.

Briefings emphasized the importance of maintaining energy and altitude. The phrase speed is life became a mantra in lightning squadrons. As long as a P38 pilot kept his speed up and stayed high, he held the advantage. The moment he slowed down and descended to the enemy’s altitude, he surrendered that advantage.

By March 1943, the North African campaign was entering its final phase. Allied ground forces were pushing from both east and west, squeezing German and Italian forces into an evershrinking perimeter in Tunisia. Air superiority became critical. German forces needed air cover to evacuate by sea and air. Allied forces needed air superiority to support ground advances and prevent German reinforcement.

The air war intensified. Missions were flown around the clock. P38 units flew multiple sorties per day, escorting bombers, conducting fighter sweeps, and attacking ground targets. The operational tempo was punishing. Pilots flew until they were physically exhausted. Maintenance crews worked 18-hour shifts keeping aircraft operational, but the Allies had the advantage of numbers and logistics.

More aircraft arrived. More pilots rotated in. Supplies flowed freely from bases in Algeria and from ships in Mediterranean ports. The Luftvafa had no such advantages. Their supply lines ran across the Mediterranean from Sicily and Italy, constantly harassed by Allied submarines and aircraft. Fuel shortages limited flight operations.

Spare parts became scarce. Replacement pilots arrived with minimal training, sometimes with fewer than 100 hours in type. These young pilots faced veterans in aircraft that outperformed their own. The attrition rate was catastrophic. The final battles over Tunisia in April and May 1943 saw some of the most intense air combat of the Mediterranean campaign. German forces attempted a fighting withdrawal, evacuating by sea to Sicily.

Luftvafa fighters provided cover for these evacuation convoys. Allied fighters, including P38s, attacked both the convoys and their escorts. One engagement on April 18th, 1943, became known among American pilots as the Palm Sunday Massacre.

A formation of nearly a 100 German transport aircraft escorted by fighters attempted to evacuate troops from Cape Bond to Sicily. They flew low over the water in tight formations. Allied radar picked them up. P38s along with Spitfires and P40s intercepted the formation over the Mediterranean. The German escorts were overwhelmed by numbers.

The transports, lumbering junkers, Jew 52s and Messmitt Mi323s were defenseless. The P38s dove through the formation, their concentrated nose armorament tearing through the thin- skinned transports. Some transports exploded in midair. Others crashed into the sea, trailing smoke and flame. German pilots in their BF-1009s tried desperately to intervene, but they were outnumbered and outpositioned.

The Lightnings used their speed to make slashing attacks and then climb away before the German fighters could respond effectively. Over 50 German transports were destroyed in less than 30 minutes. Hundreds of German soldiers died in the wreckage or drowned in the Mediterranean. The few transports that survived turned back toward Tunisia or made emergency landings on beaches. The psychological impact of this massacre was profound on both sides.

For American pilots, it was confirmation of total air superiority. They had attacked a large German formation in daylight and destroyed it almost completely with minimal losses. For German pilots and ground troops, it was a nightmare. The Luftvafer could no longer protect even largescale evacuation operations. The defeat in North Africa became inevitable.

By midMay 1943, organized German resistance in Tunisia collapsed. Over 250,000 German and Italian troops surrendered. The Luftvafa units withdrew to Sicily, having lost hundreds of aircraft and many of their most experienced pilots. The P38 had played a significant role in this outcome. It had helped establish Allied air superiority at a critical moment.

It had allowed bomber operations to proceed with acceptable losses. It had forced German fighters into defensive postures that negated their tactical expertise. As the theater of operations shifted to Sicily and then to Italy itself, the Lightning remained a key asset. Its range allowed it to escort bombers from North African bases all the way to targets in southern Italy and beyond.

Its performance at altitude made it ideal for intercepting German bombers attempting to strike Allied shipping and ground forces. Its versatility meant it could be adapted for reconnaissance, ground attack, and pure fighter missions as needed.

The lessons learned in North Africa spread throughout the American air forces. Other theaters began requesting P38s. The Pacific Theater, where long overwater flights and extreme ranges were the norm, found the Lightning particularly valuable. The top two American aces of the war, Richard Bong and Thomas Maguire, both flew P38s in the Pacific and credited the aircraft’s capabilities for their success.

In Europe, as the strategic bombing campaign against Germany intensified, P-38s flew some of the deepest penetration missions in 1943 and early 1944 before the longer ranged P-51 Mustang became available in large numbers. But the Lightning’s impact went beyond tactical success. It represented a shift in American industrial and engineering capability.

The United States had entered the war with fighter designs that were generally inferior to their German counterparts. By 1943, American industry was producing fighters that could match or exceed German performance. The P38 was one of the first clear examples of this shift. It proved that American engineers could solve complex problems with innovative designs. It proved that American factories could produce these complex designs in meaningful numbers.

and it proved that American pilots properly trained and equipped could defeat the Luftvafer’s best. For German pilots who survived the North African campaign, the memory of the P38 remained vivid. Postwar interviews and memoirs frequently mentioned the forktailed devil. Some German pilots expressed grudging respect for the aircraft’s capabilities.

Others focused on its vulnerabilities and the tactical mistakes American pilots sometimes made, but all acknowledged that it had changed the dynamic of air combat in the Mediterranean. The confidence that had carried the Luftvafer through the early years of the war had been shaken, not destroyed, but shaken. German pilots learned that they could be outrun, outclimbed, and outgunned.

They learned that American industry could produce advanced aircraft in numbers that overwhelmed German production. They learned that the war in the air was no longer a guaranteed German victory. These were painful lessons. Some German pilots internalized them and adapted their tactics accordingly, becoming more cautious and defensive.

Others refused to accept the new reality and continued flying aggressively, often with fatal results. The Luftwafer as an institution struggled to adapt to a war of attrition it could not win. The human cost of this technological and tactical shift was measured in lives. American pilots died learning how to fly the Lightning effectively in combat.

German pilots died trying to counter an aircraft that challenged everything they had been taught about air superiority. Ground crews on both sides worked themselves to exhaustion maintaining their aircraft. Mechanics died in aircraft accidents. Intelligence officers struggled to make sense of conflicting combat reports.

Commanders made decisions that sent men into situations where survival was uncertain. Behind the statistics and the technical specifications were individuals, young men in their early 20s, some even younger, who found themselves thrust into life or death situations at 300 mph and 25,000 ft. The P38 pilot who chased a BF-1009 across the Tunisian desert in November 1942 was a 22-year-old from California.

He had graduated from flight school 6 months earlier. Before the war, he had worked in his father’s hardware store. He flew 38 combat missions before being shot down in April 1943. He survived the crash and was captured. He spent the rest of the war in a prisoner of war camp. The German pilot he had chased in that first engagement survived the war. He flew over 300 combat missions on multiple fronts.

He was shot down four times and wounded twice. After the war, he worked as a commercial pilot. In the 1970s at an air show in the United States, he met the American pilot who had nearly shot him down over Tunisia. They talked for hours comparing their memories of that brief violent encounter three decades earlier.

These personal stories remind us that the machines, as impressive as they were, were tools used by human beings under extraordinary stress. The P38 was a remarkable aircraft. Its twin boom design, its turbo supercharged engines, its concentrated firepower, and its long range made it a formidable weapon. But it was the pilots who learned to exploit these advantages and the ground crews who kept the aircraft flying who turned potential into reality. The BF-1009 was an excellent fighter refined through years of combat.

But it was designed for a different kind of war, one where Germany held the initiative and could dictate terms. When faced with an opponent that matched its performance and came in overwhelming numbers, the 109’s advantages became less decisive.

The pilots flying it adapted as best they could, but they were fighting against industrial and technological trends they could not control. The shock that German pilots felt when they first encountered the P38 was not just surprise at an unexpected aircraft. It was the beginning of a realization that the tide of the war was turning.

That German air superiority, once taken for granted, was slipping away, that the Allies were not just catching up, but in some areas surpassing German capabilities. This was a profound psychological shift, one that reverberated through the ranks of the Luftvafer and eventually through German military planning at the highest levels.

The story of the P38 versus the BF-1009 in North Africa is not simply about one aircraft being better than another. It is about how technological innovation, industrial capacity, tactical adaptation, and human courage combined to shift the balance of a campaign and ultimately a war.

The Lightning gave American pilots a tool that allowed them to compete on equal terms with an enemy they had been taught to fear. It gave Allied commanders the ability to conduct deep strike operations that had previously been impossible. And it forced the Luftvafer to confront the reality that they no longer controlled the skies. By the time the North African campaign ended in May 1943, the psychological transformation was complete.

American pilots flew with the confidence of men who knew their aircraft, and their skills were equal to any challenge. German pilots flew with the knowledge that they faced an opponent who could match them and who came in numbers they could not overcome. The forktailed devil had delivered a message. The age of unchallenged German air superiority was over. The Lightning’s operational service continued through 1944 and into 1945.

It served in every theater of the war. It was gradually supplanted by more specialized designs like the P-51 Mustang in Europe and supplemented by newer fighters in the Pacific. But its impact during the critical period of 1942 and 1943 remained significant. It helped turn the tide when the tide needed turning most.

In the postwar years, military historians and aviation enthusiasts studied the P38’s design and operational history. Its unconventional layout inspired debates about optimal fighter configurations. Its success demonstrated that innovation could overcome established design orthodoxies. Aircraft designers in multiple countries studied its features, particularly the turbo supercharger installation and the counterrotating propeller system.

Some of these concepts influenced jet fighter designs in the early cold war period. The Lightning also became part of popular memory. Its distinctive appearance made it easily recognizable. War correspondents had photographed it extensively. Film footage showed it in action over Europe and the Pacific. For the generation that fought the war, the P38 was a symbol of American industrial might and technological innovation.

For subsequent generations, it became an iconic image of World War II aviation, instantly recognizable and forever associated with the struggle for air superiority. The German pilots who faced it remembered it differently. For them, it represented the moment when the certainties they had relied upon began to crumble.

The moment when being a Luftvafa pilot stopped being a guarantee of victory and became a struggle for survival. Some spoke of it with professional respect, analyzing its strengths and weaknesses with the detachment of technical experts. Others remembered it with something closer to fear, recalling the shock of being unable to escape or outclimb an enemy they had expected to dominate.

These memories recorded in postwar interviews and memoirs provide a window into the psychological dimension of technological warfare. The machines mattered. The P38’s speed, climb rate, firepower, and range were all measurable advantages, but the psychological impact of those advantages, the way they affected pilot behavior and command decisions was equally important. When a pilot believes he has the better aircraft, he fights aggressively.

When he doubts his machine’s capabilities, he fights defensively. The P-38 shifted that psychological balance in the Mediterranean theater in late 1942 and early 1943. It gave American pilots reason for confidence and German pilots reason for caution. That shift multiplied across hundreds of individual combats and dozens of major engagements helped determine the outcome of the campaign.

The morning of November 23rd, 1942, when that German pilot looked back and saw a twin boom fighter staying with him through a dive and climb, marked a turning point. Not the only turning point in the air war, certainly not even the most decisive, perhaps, but a turning point nonetheless, a moment when assumptions were challenged and found wanting.

a moment when the trajectory of the war shifted imperceptibly to those living through it, but clearly visible in retrospect. The P38 Lightning did not win the war by itself. No single weapon system ever does, but it contributed to victory at a critical time and in a critical theater. It gave the allies an edge when edges were desperately needed, and it delivered a shock to the Luftvafer that resonated far beyond the immediate tactical outcomes of individual battles.

The forktailed devil proved that American engineering could match German innovation, that American pilots could defeat German veterans, that the industrial might of the United States, once fully mobilized, could produce weapons that changed the character of warfare.

These were lessons that both sides learned in the skies over North Africa between November 1942 and May 1943. Lessons written in contrails and gun camera footage. Lessons paid for with the lives of pilots on both sides. Lessons that shaped the course of the war and the world that emerged from it. Thank you for watching. For more detailed historical breakdowns, check out the other videos on your screen now.

And don’t forget to subscribe.

News

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled The morning fog hung…

CH2 When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless At 9:27 a.m. on December…

CH2 Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day May 18th, 1944,…

CH2 How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells

How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells November 14th, 1942, Philadelphia Navy Yard,…

End of content

No more pages to load