German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted Defeat Against The Army That Never Starved

December 17, 1944. The forest was silent except for the steady crunch of boots over frozen soil. The air bit deep and sharp into every lungful of breath, carrying the scent of pine, cordite, and death. A gray dawn hung low over the Ardennes, its dim light filtering through branches heavy with frost. The Battle of the Bulge had begun in chaos, with German forces pushing through the American lines in a final, desperate offensive.

Along a narrow clearing near St. Vith, a group of German officers gathered around what remained of a hastily abandoned American position. The snow was churned with boot prints and the blackened scars of shell bursts. Scattered among the wreckage were rifles, empty ammunition boxes, torn maps—and small, neatly packed parcels lying in the snow like discarded treasures.

Oberführer Klaus Dietrich, commander of the 116th Panzer Division’s logistics unit, crouched to pick one up. His fingers, wrapped in cracked leather gloves, felt the slick cardboard surface—printed letters in English, stamped in bold black ink: “U.S. Army Field Ration, Type K.” He turned it over in his hands, the weight light but balanced, the corners sealed tight. Inside, something rattled.

Behind him, his aide, Hauptverfer Krueger, chuckled softly. “Leave it to the Americans to fight a war with candy boxes,” he said.

Dietrich said nothing for a moment. He had been in uniform since before the First World War, had fought in Poland, France, and now Belgium. He had commanded men who lived off horse meat and potato peel soup, men who scraped frost from the edges of helmets just to melt it for water. He had seen entire divisions run on air and adrenaline when the supply trains failed to arrive.

And here, scattered in the mud, lay the evidence of an enemy that seemed to live in a different world entirely.

He tore open the package, paper crackling under his calloused hands. Out spilled tins and packets, each labeled with methodical precision: “Meat and Beans,” “Biscuits, K-1,” “Chocolate D Bar,” “Coffee, Instant, Soluble.” There was even a folded piece of wax paper containing four small rectangles—chewing gum.

“Look at this,” he muttered, holding it up for the men around him. “They package their food like Christmas gifts.”

The officers around him laughed—a thin, brittle laughter that came more from exhaustion than amusement. They were gaunt, hollow-eyed, faces drawn tight by hunger and cold. They laughed because it was easier than admitting what they were truly thinking.

For years, German soldiers had been told that the Americans were soft. That they were factory men and farm boys pretending at soldiering, that they fought with machines, not with courage. These brightly labeled boxes seemed to prove it—food too fine for war, made by people who had never known real hunger.

But beneath that laughter lurked something darker, an unspoken awareness that these little boxes represented a kind of power they no longer possessed.

Dietrich pried open the small tin of meat and held it close to his face. The smell alone made him pause. It was rich, savory, unmistakably beef—seasoned and cooked, not raw or reconstituted. He dipped a finger into the cold fat that had congealed on top and tasted it. For a moment, his expression didn’t change. Then his jaw tightened.

“This is real,” he said quietly. “Not filler. Not offal. Real meat.”

Krueger raised an eyebrow. “You’re certain?”

“I’ve eaten worse things than shoe leather this month,” Dietrich said, wiping his fingers on his coat. “I know the difference.”

The others fell silent. Around them, the sound of distant artillery rumbled through the forest, but for a moment, no one moved. One of the younger officers, a lieutenant barely out of cadet school, knelt to pick up another box. He read the printed instructions out loud in halting English. “One—meal—breakfast. Eat from box or heat in tin.” He glanced up, confused. “They give their men choices?”

“They give their men everything,” Krueger said grimly.

In truth, what they held was more than a ration—it was the product of an entire nation’s imagination, wrapped in cardboard and sealed in wax. The K-ration had been designed by an American physiologist named Ancel Keys, a scientist from the University of Minnesota who had been asked to solve a problem no European army had ever dared to contemplate: how to feed soldiers anywhere on earth, under any condition, for as long as necessary.

Keys had studied the human body’s caloric needs under stress. He had calculated, tested, refined. The result was a meal that provided 3,000 calories per day in three simple boxes—breakfast, dinner, and supper—each engineered to fit into a soldier’s pockets. Every gram was accounted for: fats for endurance, sugars for quick energy, proteins for strength. Even the cigarettes and gum served a purpose, calming nerves, keeping mouths moist, and disguising the taste of fear.

To the German officers who now examined them, it looked like luxury. But it was something more profound. It was efficiency born of abundance—industrial strength applied to the oldest problem in war: hunger.

For them, hunger was not theoretical.

By late 1944, German rations had been cut to a level that no longer sustained fighting strength. Soldiers on the front received less than 2,000 calories a day when supplies arrived on time, which they often didn’t. The so-called “iron ration,” once designed to supplement, had become the main course. A few hundred grams of canned meat, a handful of hard bread, maybe some ersatz coffee brewed from roasted acorns or barley.

They were fighting a mechanized war on empty stomachs.

The Wehrmacht’s logistical system had been built for conquest, not endurance. Its supply trains assumed victory—that captured farms, factories, and fields would feed the army. It worked in Poland. It worked in France. But as the war dragged on and the frontlines stretched across continents, the system began to collapse under its own assumptions. The Germans had learned to scavenge what they could from occupied lands, but the lands were gone now—retaken or bombed to dust.

The Americans, by contrast, fought as if the entire world were a supply depot. Their food came from Iowa and Kansas, their trucks from Detroit, their ammunition from Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. They could land on a foreign beach and within days erect full kitchens capable of serving thousands of hot meals. Their ships carried floating bakeries, ice cream machines, even portable slaughterhouses.

It was not merely organization—it was imagination supported by limitless production.

Dietrich dropped the empty can at his feet and rubbed his temples. He had been raised on German efficiency, trained to believe that precision and discipline would always triumph over chaos and excess. But this—this was something new. An enemy that treated logistics not as an afterthought, but as a weapon.

“Cigarettes,” Krueger said suddenly, pulling a pack from another box. “Lucky Strikes. Real tobacco.” He struck a match and inhaled. The scent of it filled the air, sharp and rich. For a brief moment, even the wind seemed to pause. “My God,” he whispered. “They even smoke better than we do.”

No one laughed this time.

The truth was becoming undeniable. What the German officers had once dismissed as decadence was beginning to look like strategy. The Americans weren’t spoiled—they were prepared. They weren’t soft—they were sustained.

Dietrich crouched again, his breath forming small clouds in the air. “They fight on full stomachs,” he said quietly. “We fight on pride.”

Krueger looked down at the rations scattered across the snow. “And when pride runs out?”

The older man didn’t answer. The question hung there, fragile as the frost.

In the distance, the sound of engines began to echo through the forest—low, mechanical, steady. Dietrich turned his head toward it, his expression unreadable. Then he straightened, the discarded ration box still in his hand.

He turned it over once more, studying the English words printed across the side. “Property of U.S. Army,” it read in bold type, followed by smaller letters that almost seemed to taunt him. “For troops in the field.”

For troops in the field.

For men who would never know the gnaw of hunger, the hollow ache in the stomach that blurred the line between exhaustion and despair.

Around him, his officers began to drift away, pulling their coats tighter, their laughter gone. Dietrich stayed a moment longer, staring down at the snow where American food gleamed faintly against the gray dawn.

He didn’t know yet what it meant in full—but he understood enough to feel the weight of it.

Somewhere beyond the trees, beyond the mist and the frost, an army was moving—an army that could fight indefinitely, that could feed itself on the promise of a nation that had never starved.

And standing there, with an empty ration box in his frozen hands, Oberführer Klaus Dietrich realized that for the first time in his career, the battle before him was not just about territory or tactics.

It was about hunger—and the simple, unstoppable power of those who never had to feel it.

Continue below

December 17th, 1944. The frozen earth of the Arden’s forest crunched beneath Vermach boots as German officers surveyed their latest prize. Dozens of captured American soldiers, their breath visible in the bitter Belgian morning air. Among the scattered equipment lay something that would make the German officers pause, then smirk with contempt.

Small rectangular boxes stamped with unfamiliar letters. Krations, field rations from an army they believed to be soft. Pampered by the comforts of a nation that had never known true hunger on its own soil, Oberfurer Klaus Dietrich picked up one of the abandoned boxes, its contents rattling softly inside. At 42, Dietrich had commanded men through three years of increasingly desperate warfare.

His gaunt frame, like those of his subordinates, bore witness to months of dwindling supplies and shrinking rations. The German Eisern ration, their iron ration, had been reduced to a meager 300 g of canned meat and 125 g of hard bread per day. Yet here, scattered across the forest floor like discarded toys, were enemy rations that seemed almost wastefully abundant.

Look at this, Dietrich muttered to his aid. Helped Verer Krueger holding up the American Kration box. The Americans even packaged their food like gifts. Pretty boxes for pretty soldiers. The officers around him chuckled, a bitter sound that echoed through the pine trees. They had been told since childhood that Americans were weak.

Their military nothing more than a collection of factory workers and farmers playing at war. These rations seemed to confirm their prejudices overly elaborate packaging for an overly pampered army. What Dietrich and his men could not have imagined was that they were holding in their hands the physical manifestation of an industrial revolution in warfare.

A symbol of a nation that had fundamentally reimagined how armies could be fed. The kration was not merely food. It was a declaration of American industrial supremacy designed by physiologist Ancel Keys to deliver precisely 3,000 calories per day to any soldier anywhere in the world. Each box contained not just sustenance but the concentrated essence of American abundance.

Canned meat, processed cheese, chocolate bars, cigarettes, instant coffee, and even chewing gum. In that moment, as German officers examined these alien provisions, they unknowingly confronted the vast chasm between their own supply system and that of their enemy. The Vermacht’s logistics had been designed for swift campaigns, lightning wars that would secure resources from conquered territories.

American logistics had been designed for a different kind of conflict entirely. One that could sustain millions of men across multiple continents for years, fed from the inexhaustible production lines of Detroit, Chicago, and countless other industrial centers 6,000 m from any battlefield. The German military had always prided itself on efficiency, on doing more with less.

Their soldiers were taught to scavenge, to adapt, to make do with whatever the land could provide. The Halbezern ration system was built on the assumption that armies would supplement their meager official provisions with local resources, bread from French bakeries, meat from captured Soviet livestock, vegetables from Polish farms.

It was a system that worked brilliantly during the swift victories of 1939 and 1940, but had begun to buckle under the strain of global warfare and lengthening supply lines. By December 1944, the contrast between German and American provisioning had become stark beyond imagination. German soldiers were receiving roughly 2570 calories per day when supplies were good, often far less when they were not.

American soldiers in combat zones were consuming between 3,600 and 4500 calories daily through a combination of Krations, Crations, and supplementary field kitchens that served hot meals whenever tactically feasible. The German army was slowly starving. The American army was by any historical standard luxuriously fed.

Dietrich tore open the kration box with fingers stiff from cold and months of inadequate nutrition. Inside he found items that seemed to mock everything he thought he knew about warfare. A small can of processed meat. Not the gristly fatty schmaltz flesh that German soldiers had learned to tolerate, but actual recognizable beef, compressed biscuits that were not the rock hard daer brought that could break teeth, but crackers that dissolved pleasantly in the mouth.

Most incomprehensibly of all, luxuries that no rational military planner would waste precious shipping space on. chocolate bars, instant coffee crystals, and small packs of cigarettes. They ship candy to the front lines, Krueger observed, his voice carrying a mixture of disbelief and growing unease.

While our men make coffee from acorns, the Americans drink real coffee in foxholes. The joke that had begun in mockery was transforming into something else entirely. These were not the provisions of a weak army. They were the supplies of a military force so confident in its logistical capabilities that it could afford to pamper its soldiers with.

Comforts that German civilians had not seen in years. The psychology of warfare shifted in that frozen forest clearing. German officers had been conditioned to believe that hardship bred superior soldiers, that American softness would collapse under the pressure of real combat. Yet here was evidence of an entirely different philosophy.

That well-fed, well- supplied soldiers would fight better, longer, and with greater morale than those who were slowly wasting away from malnutrition. The Krations represented not weakness, but a kind of strength that Germany had never possessed, the strength of a nation that could feed its armies as abundantly in the field as at home.

When Dietrich first tasted the processed American cheese, his worldview began to crumble along with the cracker in his mouth. The flavor was rich, salty, satisfying in a way that German rations had not been for months. His aid, Krueger, bit into an American chocolate bar and closed his eyes, savoring sweetness that had become a distant memory.

Around them, other German soldiers were conducting their own reluctant tastings. their expressions shifting from mockery to confusion to a dawning terrible realization. This was not the food of a weak army. This was sustenance that could maintain fighting strength indefinitely, that could fuel advances across continents, that could support the kind of prolonged global warfare that Germany’s increasingly desperate logistics could no longer sustain.

Every kration box represented something that the Vermach leadership had fundamentally miscalculated. America’s industrial capacity was not just large. It was effectively unlimited by the standards of 1940s warfare. The numbers, had they known them, would have been even more devastating to German morale.

By 1944, American factories were producing enough Krations to feed not just their own armed forces, but significant portions of Allied armies worldwide. The Quartermaster Corps had overseen the production of over 105 million Krations since 1941. Each one representing a small miracle of food preservation, packaging technology, and industrial coordination.

Meanwhile, German food production was declining steadily with agricultural output falling by nearly 30% since the beginning of the war. Dietrich found himself eating slowly, methodically, trying to extract every calorie from the alien food. His body, accustomed to the knowing hunger that had become constant among German forces, responded to the rich American provisions with an almost shameful gratitude.

The processed meat provided proteins that had been increasingly rare in German rations. The chocolate delivered sugars and fats that his malnourished system craved desperately. Even the instant coffee, which dissolved completely in hot water instead of leaving the bitter drags of airs substitutes, seemed like a small miracle. “How many of these do you think they produce?” Krueger asked quietly, turning the empty Kration box over in his hands, studying the printing, the careful design, the obvious industrial sophistication of something meant to be

thrown away after a single use. The question hung in the frigid air like their visible breath. How many indeed? The answer, millions upon millions rolling off production lines in quantities that dwarfed Germany’s entire food distribution system, was beyond their imagination. The implications were staggering.

If Americans could afford to package individual meals with this level of care and abundance, what did that suggest about their overall production capacity? If they were shipping chocolate and coffee to frontline troops, what luxuries were available to workers in their factories? If their soldiers were this well-fed, how were they equipping their tanks, aircraft, and artillery? The Krations were not just food.

They were intelligence about an economy so vast and productive that it could treat as routine what Germany could achieve only through extraordinary effort. Word of the American rations spread through German units with remarkable speed. Soldiers who had been surviving on increasingly meager portions of bread, Ersat’s coffee, and whatever supplementary food they could scavenge found themselves confronting evidence of an enemy force that was not just better equipped, but better fed than many German civilians. The psychological

impact was profound and immediate. Armies throughout history had marched on their stomachs. What did it mean to face an army that marched on stomachs filled with chocolate and real coffee? The contrast became more pronounced as winter deepened. German supply lines stretched across a continent and constantly harassed by partisan attacks delivered increasingly irregular and inadequate provisions.

Soldiers grew accustomed to the hollow ache of hunger, to the weakness that came from bodies consuming their own muscle mass to maintain basic functions. They learned to make thin soups from potato peels, to stretch small portions of meat across entire squads, to find sustenance in foods that would have been rejected as animal feed in peace time.

American forces meanwhile continued to receive not just adequate rations but a variety of them. Krations for combat situations, sea rations for longerterm field use, and whenever possible, hot meals prepared by field kitchens that could produce fresh bread, hot soup, and even occasionally fresh meat. The American military had solved the fundamental problem that had plagued armies since ancient times.

how to maintain fighting strength over extended campaigns without depleting local resources or establishing vulnerable supply lines. The solution lay in American industrial capacity, but also in American agricultural abundance. The United States in 1944 was producing not just enough food to feed its own population and military, but enough to send significant portions overseas through the lend lease program.

American farmers using mechanized equipment and modern agricultural techniques were achieving yields per acre that European farmers could barely imagine. The same industrial revolution that was producing tanks and aircraft was also revolutionizing food production and preservation. German intelligence officers when they finally began to analyze captured American provisions systematically discovered details that should have terrified their leadership.

The dates stamped on krations revealed production schedules that suggested truly massive manufacturing capacity. The ingredients lists showed access to resources, real coffee, genuine chocolate, processed meats that German forces could not obtain even for special occasions. Most significantly, the casual wastefulness with which American soldiers sometimes discarded, partially consumed rations, suggested a level of abundance that was almost incomprehensible to men who had learned to save bread. crusts.

By January 1945, as the Battle of the Bulge ground to its inevitable conclusion, German officers like Dietrich were making increasingly desperate calculations. Their own men were weakening from malnutrition. Just as American forces appeared to be maintaining full fighting strength despite months of intensive combat, the Krations had become more than food.

They had become symbols of an industrial and agricultural capacity that Germany simply could not match, no matter how efficiently they organized their remaining resources. The moment of final realization came not in any single dramatic event, but in the accumulation of small observations that collectively painted an undeniable picture.

American wounded who were captured appeared healthier than many German soldiers who had never been injured. Discarded American equipment showed signs of casual abundance. Tools thrown away rather than repaired. Equipment abandoned rather than salvaged. Supplies destroyed rather than left for enemy use.

Everything suggested a military force backed by production capacity so vast that individual items had no meaningful value. In his final report to higher command dated February 3rd, 1945, Dietrich wrote words that would prove prophetic. The enemy’s strength lies not merely in superior numbers or equipment, but in a complete system of abundance that we cannot hope to match.

Their soldiers eat better in foxholes than our officers eat in garrison. This is not the decadent weakness we were told to expect, but a form of strength against which our traditional efficiencies are inadequate. The kration had become, in the end, a revelation, not of American weakness, but of American power, expressed in its most fundamental form, the ability to feed an army so well that chocolate and coffee became routine rather than luxuries.

German officers who had begun by mocking these provisions ended by understanding that they represented something unprecedented in military history. An army that truly never starved, supported by a homeland that could produce abundance as easily as scarcity. The war would continue for three more months after Dietrich wrote his report.

But the psychological victory had already been won in that frozen forest clearing where German officers first tasted American rations. They had confronted not just better food, but a better understanding of how wars were actually won. Not through superior discipline or tactical brilliance alone, but through the unglamorous but decisive advantage of superior logistics sustained by superior production capacity.

In the quiet moments before surrender, as German forces retreated across a landscape they could no longer defend, many officers found themselves remembering not the great battles or stirring speeches, but the simple taste of American chocolate dissolving on their tongues. It was a small thing perhaps, but it had revealed a truth too large to ignore.

They had been fighting not just an army, but an entire civilization organized around principles of abundance. rather than scarcity, efficiency rather than desperation, industrial confidence rather than military tradition. The Kratan boxes scattered and empty now across a dozen European battlefields had delivered their final message.

America had not won through superior courage or tactical innovation, though both had played their part. America had won because it had solved the fundamental equation of modern warfare. how to project not just military force but industrial abundance across global distances for sustained periods. The army that never starved had proven that in industrial warfare, logistics were not merely support for combat operations.

They were combat operations waged in factories and farms as decisively as on battlefields. And in the end, German officers who had learned to smirk at American rations discovered that they had been mocking their own defeat, packaged in small rectangular boxes and delivered with the casual abundance of a nation that had reimagined war itself.

News

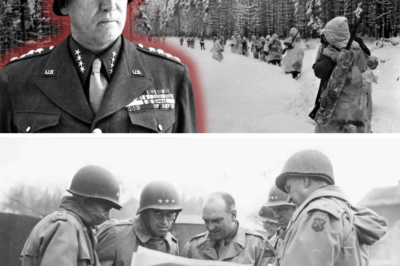

CH2 December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – Patton Turned 250,000 Men In 48 Hours

December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – Patton Turned 250,000 Men In 48 Hours December 19,…

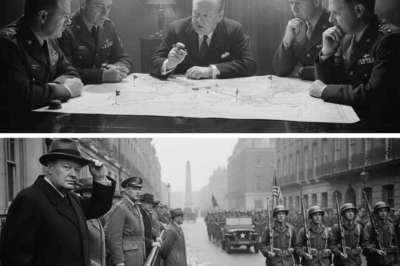

CH2 What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time

What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time December 7, 1941. It…

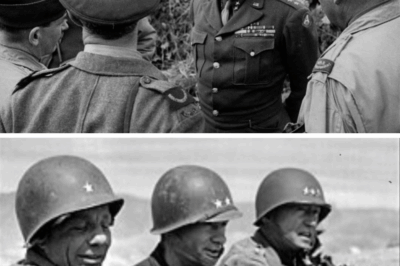

CH2 Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult

Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult On the morning of August 3rd, 1943, the…

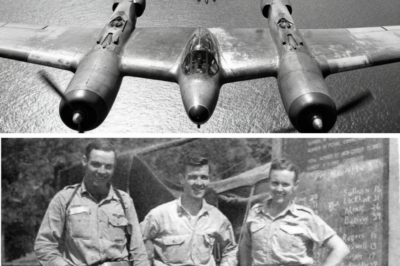

CH2 Japanese Air Force Underestimated The US – They Was Utterly Stunned by America’s Deadly P-38 Lightning Strikes

Japanese Air Force Underestimated The US – They Was Utterly Stunned by America’s Deadly P-38 Lightning Strikes The morning air…

CH2 They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs At 8:44 a.m. on June…

CH2 They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle

They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle July 23, 1943. 0600 hours. The Sicilian…

End of content

No more pages to load