German Mockery Ended — When Texas Oilmen Fueled The Army Hitler Couldn’t Stop

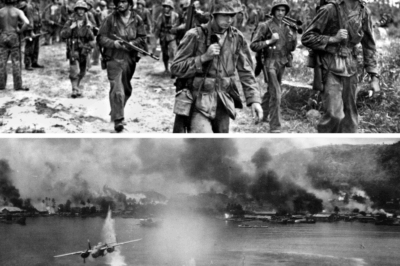

August 12th, 1944, outside the Normandy village of Morton, France, Hans von Luck stood beside his stalled Panther tank, his eyes scanning the horizon for some sign of salvation. The morning air was thick with smoke, dust, and the smell of cordite from the distant artillery, but what weighed heaviest on him was the sight of his own immobilized armor. The fuel gauge in front of him rested stubbornly at zero. His 125th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had received orders to counterattack the American breakthrough at Evanch, orders that could mean the difference between holding their line and watching it collapse entirely. The mission was critical. Every officer and soldier knew it. Yet here he stood, staring at tanks that could neither move nor fight, and the reality of their situation sank in with suffocating clarity.

His adjutant, Oburst, approached hesitantly, knowing the answer would infuriate him. “The fuel convoy was destroyed by Allied aircraft near Allosa, sir,” he reported. “The division has enough fuel for perhaps fifty kilometers—maybe less.” Von Luck’s fist met the cold steel of the Panther’s hull in frustration. “Fifty kilometers? The Americans are two hundred kilometers ahead, and they’re moving faster than we can even imagine. How can we fight when we can’t even reach the battlefield?” His radio operator tried to offer some consolation, a lifeline of rational hope. At least there is synthetic fuel production, he said. At least the Americans are shipping everything across the Atlantic. Surely their logistics will collapse soon. They can’t possibly sustain supply lines stretching all the way from Texas to France.

Von Luck wanted to believe it. German intelligence insisted that American fuel supplies were overextended, that their logistical network would falter under the strain of transatlantic transport. But as he looked up, the clouds parted to reveal a sky alive with the engines of American bombers and fighters, moving in a seemingly endless stream toward their distant objectives. The scale of the operation was staggering. Thousands of tons of fuel, fuel that allowed these aircraft to range far beyond the European coast, bomb strategic targets, and support advancing armies. And suddenly, Hans von Luck understood the terrifying truth: the Americans had enough fuel to keep their forces moving, attacking, and winning. Their energy, both literal and metaphorical, was unmatched.

Nine months later, von Luck would surrender to American forces in northern Germany. His last Panther tank would sit abandoned, not because it had been destroyed in battle, but because there was no fuel, not a single drop left to drive its mighty engine. Synthetic fuel plants lay in ruins, fuel depots emptied or destroyed, and the once-mighty Panzer divisions found themselves immobile, not through defeat in combat, but through an absence of the lifeblood of modern warfare. It was oil—Texas oil, Oklahoma crude, the relentless flow of gasoline from the United States—that had quietly, decisively, crippled the Wehrmacht. This was a war won not only by courage or strategy, but by infrastructure, by logistics, by the unglamorous but crucial arteries of supply.

The story begins not on the beaches of Normandy, but in the heart of America’s oil country. It is a tale of men working rigs, managing pipelines, and transporting black gold from wells to ports, knowing that the product of their labor was transforming the world. The Red Ball Express, trucks thundering across France night and day, kept the Allied armies supplied. Pipelines laid across the English Channel ensured that D-Day’s successes could be followed by relentless advances. And across the Atlantic, ships loaded with fuel and materiel moved inexorably toward Europe, overcoming storms, submarines, and the chaos of war. The logistics chain, invisible yet unbreakable, became a weapon more powerful than any tank, more decisive than any battlefield maneuver.

Adolf Hitler understood the importance of fuel, perhaps better than any other aspect of modern warfare. In 1934, a decade before D-Day, he had summoned Friedrich Bergius, a chemist and Nobel laureate, to the Reich Chancellery. Bergius had developed synthetic fuel production, a method to turn Germany’s abundant coal into gasoline. Hitler, tracing a finger across a map of the country, spoke with absolute certainty. “We have no oil fields. Romania supplies some, but not enough. If we are to build a great army, we need fuel. Can your process supply the Reich with enough gasoline for war?” Bergius warned that the process was expensive, that it required massive inputs of coal, water, and electricity, and that one synthetic fuel plant could cost as much as buying imported oil for years. But Hitler was adamant. “We cannot depend on foreigners for our lifeblood. Build the plants. Cost doesn’t matter.”

The Reich’s synthetic fuel program began in earnest, and by 1944 massive plants at Luna, Pollitz, Bletchhammer, and Brooks were producing roughly 124,000 barrels of synthetic fuel per day. This covered nearly 90% of Germany’s aviation fuel needs and about half of its total petroleum consumption. The achievement was impressive, a testament to German engineering and industrial might. Yet it was catastrophically insufficient. German forces consumed roughly 300,000 barrels per day during active operations, leaving a shortfall that could only be filled by dwindling stockpiles or imports from Romania. With every advance, the Panzer divisions were consuming what little fuel was available at an unsustainable rate, a reality that left commanders like von Luck facing the impossible.

Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, Commander-in-Chief West, understood the grim mathematics. In May 1944, only a month before D-Day, he sent a stark memo to the High Command: The fuel situation is critical. Panzer divisions have enough fuel for one major operation, maybe two if fortune allows. After that, mobility will vanish. He predicted with chilling accuracy that the outcome of the coming battles would be determined not by bravery or tactics alone, but by who had the energy to move, to strike, to respond. Hitler, predictably, dismissed the warnings. Synthetic fuel production is secure, he declared. The Americans are shipping fuel across an ocean riddled with submarines. Their supply lines will collapse. Ours will endure.

Meanwhile, thousands of miles away, a very different story was unfolding.

Continue below

August 12th, 1944, outside the Normandy village of Morton, France, Hans von Luck stood beside his stalled Panther tank and cursed the French sky, the Allied bombers, and most of all, the empty fuel gauge before him. His 125th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had received orders to counterattack the American breakthrough at Evanch. The orders were clear. The mission was vital.

The tanks were ready, but the fuel trucks hadn’t arrived. Her Oburst, his agitant, reported, “The fuel convoy was destroyed by Allied aircraft near Allosa. The division has enough fuel for perhaps 50 km, maybe less.” Von Luck slammed his fist against the Panthers armor.

“50 km? The Americans are 200 km ahead of us and moving fast. How are we supposed to fight when we can’t even reach the battlefield?” His radio operator offered cold comfort. At least we have synthetic fuel production, sir. The Americans are shipping everything across the Atlantic. Surely their logistics will collapse soon. They can’t possibly sustain supply lines stretching from Texas to France.

Von Luck wanted to believe it. German intelligence insisted that American fuel supplies were stretched thin, that their logistics were breaking down, that the advancing armies would soon grind to a halt for lack of gasoline. But as Von Luck watched the sky, he saw something that filled him with dread.

An endless stream of American aircraft, hundreds of them, their engines burning fuel with abandon. Where were the Americans getting all that gasoline? 9 months later, Hans von Luck would surrender to American forces in northern Germany. His final Panther tank sat abandoned, not due to combat damage, but because there was no fuel, not a drop.

The synthetic fuel plants lay in ruins. The fuel depots were empty. The mighty Panzerwaffe had been immobilized not by American guns but by American oil or rather by the absence of German oil and the abundance of American oil. This is the story of how Texas oilmen defeated the Werem. How derks in Oklahoma crushed Panzer divisions.

How the Red Ball Express outran the Blitzgreek. How pipelines laid across the English Channel proved mightier than the Atlantic Wall. This is the story of how the war was won not on battlefields, but in oil fields, not by generals, but by rough necks. Not through tactics, but through logistics, the fuel that never was. Adolf Hitler understood oil, perhaps better than he understood anything else about modern war.

In 1934, a decade before D-Day, Hitler summoned chemist Friedrich Beerios to the Reich Chancellery. Beerios had won the Nobel Prize for developing synthetic fuel production, turning coal into gasoline through complex chemical processes. Herd Bearios, Hitler said, tracing his finger across a map of Germany.

We have no oil fields. Romania supplies some, but not enough. If we are to build a great army, we need fuel. Can your process supply the Reich with enough gasoline for war? Bergi is hedged. Main furer synthetic fuel production is expensive and inefficient. It requires enormous amounts of coal, water and electricity. For the cost of one synthetic fuel plant, you could buy oil from abroad for years. Hitler’s eyes hardened.

We cannot depend on foreigners for our lifeblood. Build the plants. Cost doesn’t matter. And so, Germany embarked on the most ambitious synthetic fuel program in history. By 1944, massive plants at Luna, Pollitz, Bletchhammer, and Brooks were producing approximately 124,000 barrels of synthetic fuel per day.

About 90% of Germany’s aviation fuel and 50% of its total petroleum needs. It was an impressive achievement. It was also catastrophically insufficient. German forces consumed approximately 300,000 barrels of fuel per day during active operations. Synthetic production plus imports from Romania provided perhaps 200,000 barrels daily. The shortfall 100,000 barrels per day came from stockpiles that steadily dwindled.

General Feld Marshall Gird von Runet, Commanderin-Chief West, understood the mathematics of doom. In May 1944, one month before D-Day, he sent a stark memo to the high command. The fuel situation is critical. Our panzer divisions have enough fuel for one major operation, perhaps two if we are fortunate. After that, we are immobile.

The enemy, by contrast, appears to have unlimited fuel supplies. This disparity will determine the outcome of the coming battle. Hitler dismissed the concerns. Our synthetic fuel production is secure. The Americans are shipping fuel across an ocean infested with Ubot. Their logistics will collapse. ours will sustain us.

It was a fantasy, but like so many Nazi fantasies, it was believed until reality made belief impossible. Meanwhile, 5,000 m away in Texas, a very different conversation was taking place. Black Gold and the Arsenal of Democracy. On December 8th, 1941, one day after Pearl Harbor, Secretary of the Interior Harold Iikes called an emergency meeting in Washington.

Attending were representatives from Standard Oil, Gulf Oil, Texico, Shell, and a dozen other petroleum companies. “Gentlemen,” Ike said without preamble, “we’re at war. The Army and Navy will need fuel. Lots of it. How much can you produce?” The oilmen looked at each other. Finally, J. Howard Pew of Sun Oil spoke. “Mr. Secretary, how much do you need?” “I don’t know yet,” Ike admitted. But I know it’s more than we’re producing now. Maybe twice as much. Maybe three times.

Hugh smiled. Then we’ll produce three times as much. It wasn’t bravado. It was fact. In 1941, the United States produced 1.4 billion barrels of oil per year, 63% of world production. Texas alone produced more oil than Germany, Japan, and Italy combined. Oklahoma, California, and Louisiana added even more. The infrastructure was already in place.

Thousands of producing wells, hundreds of refineries, tens of thousands of miles of pipeline. American oil production didn’t need to be built from scratch like German synthetic fuel plants. It just needed to be expanded. And expanded it was. By 1945, US oil production reached 1.7 billion barrels per year. New wells were drilled in Texas, Oklahoma, California.

Refineries operated 24 hours a day. Pipelines were laid at record speed to move crude from fields to refineries and refined products to ports. But production was only half the challenge. The fuel had to reach Europe. In 1942, German Ubot were sinking tankers faster than America could build them. The Atlantic became a graveyard for fuel shipments.

Of the 681 tankers sunk during the war, most went down in 1942 to 1943. The solution was vintage American ingenuity. Build tankers faster than hubot could sink them. The Kaiser shipyards in California pioneered techniques that reduced tanker construction time from 1 year to 45 days. Welding replaced riveting. Pre-fabrication replaced custom construction. Assembly line methods replaced traditional ship building.

Henry J. Kaiser, the same industrialist who revolutionized tank production, turned ship building into mass production. His yards launched tankers so fast that German intelligence refused to believe the numbers. The Americans claimed to build ships in weeks, one German naval intelligence report scoffed. Impossible. They are inflating figures for propaganda. They weren’t.

By 1943, American shipyards were launching three ships per day. The Ubot couldn’t keep up. But even with tankers secured, another problem loomed. How to fuel an army racing across France faster than supply lines could follow. The Red Ball Express logistics at 50 mph. On July 31st, 1944, Lieutenant General Georgees Patton’s third army broke out of the Normandy Hedgeros and exploded eastward.

In 2 weeks, his tanks advanced 400 m from Avranch to the outskirts of Paris. It was the fastest sustained advance in modern military history. It was also a logistical nightmare. Patton’s army consumed 400,000 gallons of gasoline per day. Every mile, his tanks advance stretched supply lines another mile longer.

By late August, Third Army was 400 m from the nearest supply depot and still attacking. Traditional military logistics said the advance should halt until supply lines caught up. Patton said something unprintable and demanded fuel. On August 25th, 1944, the US Army activated the Red Ball Express, the most ambitious trucking operation in military history. The concept was simple.

Dedicate roads exclusively to supply trucks running in a continuous loop from Normandy ports to forward supply dumps. No civilian traffic, no military traffic except supply trucks. Just fuel, ammunition, and food racing forward in an endless convoy. The execution was anything but simple.

Major Gordon Grall, operations officer for the Red Ball Express, described the challenge. We needed to move 12,000 tons of supplies per day over roads that weren’t designed for heavy truck traffic through a country with bombed bridges and cratered highways to an army that was advancing. was so fast we could barely plot where they’d be tomorrow. The solution was characteristically American.

Throw resources at the problem until it worked. 6,000 trucks were assigned to the Red Ball Express. Each truck made a round trip every 3 days. Load at Normandy beaches. Drive 400 m to forward dumps. Unload. Drive 400 m back. Reload. Repeat. The trucks ran 24 hours a day. Drivers worked in shifts, sleeping while their relief drove.

When trucks broke down, they were pushed off the road and cannibalized for parts. Replacement trucks rolled forward from the ports. 75% of Red Ball Express drivers were African-Amean soldiers from segregated transportation units. They drove through rain, mud, darkness, and occasional German attacks. They drove until they collapsed from exhaustion, then got back in the truck and drove some more.

We knew the whole advance depended on us, recalled Corporal Charles Stevenson of the 3,898th Quartermaster Truck Company. Every gallon of gas we delivered meant Patton’s tanks could advance another mile. We weren’t combat soldiers, but we were winning the war one truckload at a time. The statistics were staggering.

Peak daily runs 900 truck trips fuel delivered 300,000 gall per day minimum often exceeding 500,000 gallons total tonnage August Nov 1944 412,193 tons total vehicle miles 96 million m accident rate surprisingly low despite exhaustion and speed but even the red ball express couldn’t fully keep up with Patton’s advance in September 1944 Third Army literally ran out of fuel 50 mi short of the German border.

“Patton was apoplelectic.” “My men can taste the rin water,” he shouted at supply officers. “We could be in Germany in a week if you just get me gasoline.” The supply officers had no gasoline to give. The Red Ball Express was running at maximum capacity. The ports were unloading at maximum capacity.

The tankers were arriving as fast as possible. The problem wasn’t effort. It was physics. Trucks could only move so much fuel so fast. The Americans needed a better solution. They founded in one of the war’s most audacious engineering projects, Pluto, the pipeline under the ocean.

In August 1944, while the Red Ball Express raced across France, British and American engineers were completing a project that seemed like science fiction. A fuel pipeline running beneath the English Channel. Operation Pluto, Pipeline Under the Ocean, was conceived in 1942 when planners realized that postinvasion fuel demands would exceed what tankers and trucks could deliver. The solution, pump fuel directly from England to France through underwater pipelines.

The engineering challenges were immense. The pipeline had to withstand water pressure at 180 ft depth resist corrosion from seawater flex with tidal currents without breaking deliver millions of gallons without leaking be installed quickly and secretly. British engineers developed two pipeline types. Heist Hartley Anglo-Iranian seammens, a flexible cable made of steel wire wrapped around lead tubing and Haml named after designers HJ Hammock and BJ Ellis made of lead with a steel wire reinforcement.

The pipes were wounded on giant floating drums called conundrums that were towed across the channel while unreing pipeline behind them like thread from a spool. The first Pluto line from the aisle of White to Sherberg became operational on August 12th, 1944. By September, it was pumping 100,000 gall per day.

Eventually, 23 pipelines were laid with capacity exceeding 1 million gall per day. But Pluto was just the beginning. As Allied forces advanced into France and Belgium, engineers laid pipelines across land with astonishing speed. The Army’s 835th Engineer Battalion specialized in rapid pipeline construction using techniques developed in the Texas oil fields.

They could lay 10 to 15 mi of 6in pipeline per day. Major Ernest Johnson, commander of the 835th, explained, “We treated Europe like a giant oil field. Every major advance required pipeline to follow. We laid pipe from Sherberg to Paris, from Paris to the German border, from Antwerp into Germany. Wherever the tanks went, pipeline followed.

By the end of 1944, over 1,200 m of pipeline crisscrossed France and Belgium. The system could deliver 75,000 gallons of fuel per day per pipeline, the equivalent of 300 tanker truckloads. The Germans had nothing comparable. Their fuel moved by rail vulnerable to bombing or truck limited capacity.

As Allied bombers systematically destroyed German refineries and rail networks, fuel distribution collapsed even when fuel existed. The starvation, German armor immobilized. While American engineers laid pipeline, German Panzer commanders watched their fuel gauges drop to empty and stayed there. September 1944, the second Panzer division sat immobilized near Mets with 120 operational tanks and enough fuel for approximately 30 km of movement.

Orders arrived to counterattack American forces crossing the Moselle River 100 km away. Division commander General Major Minrad von Lurch radioed back. Cannot comply. Insufficient fuel. The response fuel shipment on route. attack tomorrow. The fuel shipment never arrived. Allied aircraft had destroyed it 50 km behind the lines. For 3 weeks, the second Panzer Division, one of the Weremach’s finest formations, sat idle while American forces advanced unopposed, not because they lacked tanks, not because they lacked will, because they lacked gasoline. This scene repeated across the

Western Front throughout late 1944 and early 1945. October 1944, the 9inth Panzer Division near Arnham had 60 operational tanks, but no fuel to engage British forces withdrawing from Market Garden. A perfect opportunity for counterattack wasted because tanks couldn’t move.

November 1944, the 116th Panzer Division received orders to move from the Aen sector to the Arden for Hitler’s winter offensive. The 90 km journey took 11 days because the division had to wait for fuel deliveries in small batches. December 1944, during the battle of the bulge itself, Germany’s last major offensive, Panzer divisions ran out of fuel within days.

The second Panzer division reached Celis just 5 km from the Muse River, then stopped. Empty tanks, no fuel, surrounded and destroyed. Oburst Minrad von Lert, now commanding Panzer Lair division in the Bulge, wrote in his war diary, “We have reached our objectives. The Americans are in retreat.

The Muse bridges are within sight, and we sit here immobile, waiting for fuel that will never come.” Meanwhile, American tanks, inferior to ours in every technical specification, roar past with full fuel tanks. They are not better soldiers. They simply have gasoline and we do not. The fuel starvation created a death spiral for German armor.

Lack of fuel limited movement limited movement prevented concentration of forces dispersed forces couldn’t achieve decisive results. Indecisive results meant continued allied pressure. Allied pressure destroyed fuel infrastructure. Destroyed infrastructure meant even less fuel. By January 1945, German Panzer divisions were receiving approximately 20% of their fuel requirements. By March, less than 10%. By April, virtually nothing.

When the final Soviet offensive encircled Berlin in April 1945, dozens of Tiger and Panther tanks sat abandoned in the streets, mechanically sound, but completely out of fuel. Crews set them on fire to prevent capture. The mightiest tanks in the world rendered useless for lack of the one thing America had in abundance, petroleum.

The abundance, Americans swimming in gasoline. The contrast couldn’t have been starker. While German tanks sat immobilized, American armored divisions operated with such fuel abundance that it seemed wasteful. Captain Belton Cooper of the Third Armored Division’s Maintenance Battalion recalled, “We had so much gasoline, we literally didn’t know what to do with it all.

Our fuel dumps had thousands of jerikans stacked like mountains. Trucks arrived daily with more. We used fuel extravagantly because we could. American tankers idled their engines to stay warm. They drove ciruitous routes to avoid difficult terrain.

They ran reconnaissance patrols that consumed hundreds of gallons for minimal intelligence gain. They did all of this because fuel was never a limiting factor. Patton’s Third Army consumed 400,000 gall per day during active operations, equivalent to Germany’s total refined fuel production for all purposes. And Third Army was just one of several American armies in Europe.

The US First Army consumed another 400,000 gallons daily. The 9inth Army another 300,000. The Seventh Army in southern France another 200,000. British and Canadian forces added even more demand. Total Allied fuel consumption in Europe, approximately 2 million gallons per day at peak operations. This was possible because Texas oil fields were producing 1.

7 million barrels per day, 71.4 million gallons. Just Texas alone could theoretically fuel the entire European theater and have fuel left over. Refineries operated at maximum capacity, converting crude to aviation fuel, motor gasoline, diesel, and lubricants. Tanker fleet had grown from 389 vessels in 1942 to over 700 by 1944, each capable of carrying millions of gallons. Ports in Britain and France unloaded petroleum products around the clock.

By December 1944, Antworp alone was handling 26,000 tons of petroleum products daily. Pipeline network distributed fuel from ports to forward supply dumps with minimal truck transport required. Stockpiles at forward dumps ensured that even temporary supply disruptions didn’t halt operations. The system was so efficient that the limiting factor for American operations was never fuel, but ammunition, food, or replacements.

And even those were usually available in abundance. Sergeant Joe Lopez of the Fourth Armored Division described the surreal abundance. We’d pull into a village and there’d be a fuel dump with enough gas to run every car in America for a week, just sitting there, guarded by a couple of GIs and a fence. Meanwhile, we heard the Germans were siphoning fuel from knocked out tanks because they had nothing left.

The psychological impact was profound. American soldiers knew their advance would never be halted by lack of supplies. German soldiers knew their resistance would eventually be strangled by empty fuel tanks. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

American confidence bred aggressive operations that consumed enormous fuel but achieved rapid results. German despair bred cautious operations that conserved fuel but achieved nothing. The breaking point, the bulge runs dry. Hitler’s plan for the Arden offensive, Operation Wocked Mr was audacious, sophisticated, and predicated on a fantasy that German forces could capture American fuel dumps to sustain their advance.

On December 16th, 1944, three German armies crashed into American lines with approximately 1,400 tanks and assault guns. The operation required reaching the Muse River 80 km, crossing it, and advancing to Antworp, another 100 km, a total of 180 km. German quarter masters calculated fuel requirements.

Each Panzer division needed approximately 100,000 gallons to reach the Muse, another 100,000 to reach Antworp. Total requirement 5 to 6 million gallons for the entire operation. Germany’s fuel stockpiles and production could provide approximately 2 million gallons, enough to reach the muse with nothing left for the advance to Antworp. The plan assumed capturing American fuel dumps would provide the rest. It was a plan built on hope, not logistics.

The offensive began brilliantly. Within 48 hours, German forces had penetrated 40 km into American lines. Wim papers battle group of the first SS Panzer division reached Stavelot where intelligence indicated a massive American fuel dump enough gasoline to fuel the entire German offensive.

Papers lead tanks were 3 km from the dump when American engineers set it on fire. 2.5 million gallons of gasoline more than Germany’s entire monthly production went up in flames. We could see the smoke from kilome away. SS Ober Sturban Furer paper later testified. That was the moment I knew the offensive had failed. We were literally watching our hopes burn. Without captured fuel, the German advance ground to a halt within a week.

The second Panzer Division reached Celis on December 24th with empty tanks. Surrounded by American forces and unable to move, the division was annihilated. The Panzer Lair Division stalled near Baston. Out of fuel, immmobile, destroyed. The 116th Panzer Division never reached its objectives. Out of fuel. Meanwhile, American forces received unlimited fuel supplies.

The Red Ball Express, temporarily diverted during the initial German attack, resumed operations at maximum capacity. Pipeline deliveries continued uninterrupted. Tanker ships kept arriving at Antworp. By January 1st, 1945, American forces in the Arden had more fuel than they’d had on December 15th before the German attack. The Germans had none.

The Battle of the Bulge ended not because American soldiers were braver or American tactics superior, but because American trucks kept delivering gasoline and German trucks didn’t. The final equation, oil equals victory. By April 1945, the fuel situation had become apocalyptic for Germany. Synthetic fuel plants at Luna, Pitz, and Bletchhammer lay in ruins, destroyed by American bombers.

Romanian oil fields were in Soviet hands. Stockpiles were exhausted. The werem was running on fumes, literally. Luwa facortis plummeted, not because aircraft were unavailable, but because there was no fuel for them. Thousands of Mi 10009s and FW190s sat on airfields fueled only partially or not at all.

Jet aircraft, the revolutionary Mi262s that might have challenged Allied air superiority, flew limited missions because each sorty consumed fuel that couldn’t be replaced. German tanks were towed into position by horses to conserve fuel. Once in position, they became immobile pill boxes. When forced to retreat, they were abandoned.

The Americans, by contrast, operated with such fuel abundance that proflegacy became standard practice. General William H. Simpsons 9th Army crossed the Rine with 300,000 gallons of fuel stockpiled per division, enough for 10 days of intensive operations. When operations concluded in 5 days, the excess fuel was simply stockpiled for the next advance. Allied aircraft flew thousands of sorties daily.

Fighters escorted bombers, conducted ground attack missions, flew reconnaissance, and returned for more. All without fuel being a limiting factor. The statistical comparison in April 1945 was almost obscene. German fuel availability approximately 10,000 barrels per day total, mostly for critical operations. Allied fuel consumption in Europe approximately 450,000 barrels per day. Ratio 45:1 in favor of the Allies.

Albert Spear, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments, later wrote, “By the spring of 1945, we had tanks without fuel, planes without fuel, and trucks without fuel. We had soldiers willing to fight and commanders willing to lead, but we had no means to move them. The Americans had unlimited fuel and therefore unlimited mobility.

Mobility is life in modern war. We were paralyzed. They were everywhere. When Germany surrendered on May 8th, 1945, American forces discovered thousands of German vehicles, tanks, trucks, aircraft abandoned intact for lack of fuel. The Luwaffa had approximately 5,000 aircraft at surrender, most grounded permanently by fuel shortages.

The Weremach’s final collapse wasn’t primarily due to lack of manpower, equipment, or even will to fight. It was due to lack of fuel. The Texas oilman had n. The lessons written in crude. The fuel war of 1941 to 1945 taught lessons that militaries study to this day. Lesson one, logistics determine strategy. Hitler’s grand strategic visions, holding all of Europe, counterattacking in the Arden, defending Germany to the last, were logistically impossible. Strategy that ignores logistics is fantasy.

Lesson two, synthetic substitutes cannot match natural abundance. German synthetic fuel was an engineering marvel, but it cost 10 times what natural petroleum cost, required vast resources to produce, and was vulnerable to strategic bombing. America’s natural oil fields were invulnerable and inexhaustible.

Lesson three, resource control is as important as tactical skill. German tank crews were arguably more experienced and tactically proficient than American crews. But tactical skill means nothing if your tank can’t move. Lesson four, industrial capacity beats military capability. Germany built better tanks, better aircraft, and better guns.

America built more tanks, more aircraft, more guns, and had fuel to run them all indefinitely. Lesson five, supply lines are as important as front lines. The Red Ball Express, Pluto, and the pipeline network were as vital to victory as Patton’s tanks or Eisenhower strategy. Lesson six, abundance enables aggression. Scarcity enforces caution.

American commanders attacked boldly because they knew supplies would flow. German commanders hesitated because every gallon of fuel consumed was irreplaceable. These lessons shaped the next 80 years of American military doctrine. The US military became the most logistics focused force in history. Wars are planned around fuel requirements.

Campaigns are designed around supply capabilities. Tactical audacity is enabled by logistical abundance. The Gulf War of 1991 saw American forces consume 1.3 million gallons of fuel per day, almost as much as the entire European theater in 1945. The logistics tales supporting combat operations was even larger than in World War II.

The lesson learned in 1944 to 45 became doctrine. When the logistics war and the shooting war takes care of itself when the last shot was fired in Europe on May 8th, 1945, the oil that fueled victory didn’t stop flowing. It pivoted immediately to peaceime purposes. The pipelines built to supply armies now supplied reconstruction. The tankers that crossed the Atlantic with gasoline now carried fuel for European recovery.

The Texas oil fields that had powered the arsenal of democracy now powered the economic boom. The rough necks who had drilled wells in West Texas. The refinery workers who had processed crude in Louisiana. The pipeline engineers who had laid Pluto across the channel. The truck drivers who had run the Red Ball Express.

They had won the war as surely as any infantryman or tank commander. They proved that modern war is won in factories and oil fields as much as on battlefields. That strategic resources matter more than tactical brilliance. That abundance defeats scarcity no matter how heroic the defenders. The Germans fought with skill, courage, and sophisticated equipment. But they fought on empty tanks.

The Americans fought with adequate equipment, improving skill, and unlimited fuel. And they simply never stopped moving. Hitler had mocked American dependence on Jewish capitalist oil cartels. He predicted that American logistics would collapse under the strain of supplying armies across an ocean. He built synthetic fuel plants to make Germany independent of foreign oil. He was wrong on every count.

The Jewish capitalist oil cartels, which were actually Texas oilmen, Oklahoma rough necks, and California engineers, produced so much oil that the Allied forces never even approached shortage. American logistics didn’t collapse. They became the most efficient in history. German synthetic fuel plants, for all their sophistication, couldn’t produce enough to keep a single Panzer army supplied.

The contrast between capitalist abundance and fascist scarcity couldn’t have been clearer. Democracy fueled by oil defeated dictatorship running on synthetic substitutes. In the end, the werem wasn’t defeated by superior American tanks or tactics. It was strangled by empty fuel tanks while American tanks inferior in almost every technical specification rolled forward on an ocean of Texas crude.

The mockery of German commanders that American logistics would fail, that dependence on distant oil fields was a fatal weakness, echoed hollow in May 1945 when those same commanders surrendered beside tanks that had plenty of ammunition but not a drop of fuel. The war was won by many factors.

American production, Soviet manpower, British determination, Allied intelligence. But underneath all of it, lubricating the entire war machine was oil. American oil, Texas oil, Oklahoma oil, California oil, the black gold that the United States had in abundance and Germany desperately lacked. In the calculus of modern war, oil didn’t just matter. Oil was everything.

News

CH2 The Decision That Saved 100,000 Lives On One Of The Most Brutal Campaign in WW2 — The Bypass of Rabaul

The Decision That Saved 100,000 Lives On One Of The Most Brutal Campaign in WW2 — The Miracle Happened in…

CH2 When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich

When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich The…

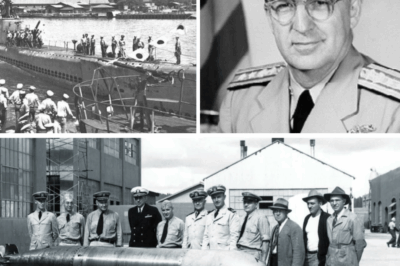

CH2 Why American Submarines Strangled Japan, While Japanese Subs Could Not Do Anything – The Man Who Bring Fears

Why American Submarines Strangled Japan, While Japanese Subs Could Not Do Anything – The Man Who Opened The Door …

CH2 German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is…

German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is… …

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came…

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came… …

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I…

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I… At…

End of content

No more pages to load