German Engineers Tried to Copy the Sherman Tank—Then Learned Its Real Secret Was Not the Armor

August 1942. North Africa. The sun hung motionless above the desert like a molten coin, turning the horizon into a wavering mirage of gold and heat. Near El Alamein, a small group of German officers and engineers from the Afrika Korps stood in a circle around what had once been an American tank. Its olive-green hull was half buried in the sand, its sides charred black, its gun barrel twisted toward the dunes like a finger pointing at nothing.

The wreck had been dragged here the day before, hauled across the desert by a pair of Sd.Kfz. 9 recovery vehicles. Now, under the relentless sun, it sat silent—a strange, foreign shape in a battlefield otherwise littered with the familiar wreckage of British Crusaders and American Grants.

Oberingenieur Friedrich Bauer, chief engineer attached to the 15th Panzer Division, adjusted his cap and walked slowly around the tank, his boots crunching in the sand. He tapped the scorched hull with his gloved knuckles. “This,” he said to the others, “is what the Americans send to war.” His voice dripped with contempt. “Too tall. Too light. Too… agricultural.”

The others laughed.

To men raised on the engineering perfection of German armor—the thick, sloped plates of the Panzer IV, the massive precision of the Tiger—the American M4 Sherman looked almost ridiculous. Its sides were nearly vertical, its silhouette high and awkward, its turret rounded in a way that looked, to German eyes, like a child’s toy cast in iron.

A junior officer, wiping sweat from his neck, chuckled. “They build tractors, not tanks.”

The laughter continued, echoing off the steel. It was the laughter of confidence—confidence built on the myth of German superiority in design, in craftsmanship, in the belief that excellence came only from the hands of master engineers. But as they circled the wreck, something began to shift.

One of the engineers, Lieutenant Hans Adler, crouched beside an open hatch and peered inside. The interior was blackened but intact. The controls—throttle, gear levers, radio dials—were still recognizable under a thin layer of soot. Adler frowned. “Look at this,” he said quietly. “Everything is labeled.”

Bauer leaned closer. “What do you mean, labeled?”

“Here,” Adler pointed. “The gear shift, the fuel cut-off, even the brake release. It’s all marked, like… like it’s meant for anyone to use.” He reached in and ran his hand along the panel. “And these gauges—standard automotive type. Not custom instruments.”

Bauer frowned, pulling a notebook from his pocket. He scribbled something down: Simple interior, automotive layout. Civilian logic applied.

He didn’t know it yet, but that simple note would echo in war archives years later as one of the earliest signs that Germany was fighting the wrong kind of war.

At that moment, the German officers saw simplicity as weakness. To them, a tank should be a masterpiece—an instrument of engineering precision so finely tuned that only experts could truly understand it. The idea that a war machine could be designed for mass use, for ease, for interchangeability, seemed almost insulting.

They didn’t realize that the Americans weren’t building machines for prestige. They were building machines for war.

By late 1942, the United States had been at war for less than a year. Yet already its industrial might was shifting into overdrive. Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler had converted car assembly lines into military factories. Detroit had become the Arsenal of Democracy, its factories running twenty-four hours a day.

For every Tiger tank Germany built, the United States produced dozens of Shermans—each nearly identical, each built to be repaired in the field, not revered in a museum.

As Bauer and his team examined the burned Sherman, their focus stayed on the physical: the armor thickness, the gun size, the engine configuration. They saw only what was in front of them—the shape, the steel, the imperfections. They couldn’t see what lay behind it: a nation that had turned mass production into a weapon.

One American soldier later put it best: “They built Tigers like jewelry. We built Shermans like hammers.”

Germany believed that perfection would win wars. America believed production would. And production—relentless, fast, efficient—was a kind of power the Germans could not yet understand.

As the desert wind began to rise, fine sand whipped across the wrecked hull, coating it in dust once more. The engineers packed up their instruments and their notes, unaware that they were walking away from a symbol of their own undoing. The future of warfare would not belong to the strongest or the most elegant—it would belong to the side that could build, repair, and replace faster than the enemy could destroy.

Winter, 1943. Kummersdorf Proving Grounds, south of Berlin.

Snow dusted the roofs of the vast concrete hangars, and inside, the air reeked of oil, steel, and cigarette smoke. Beneath the glow of hanging floodlights, a crowd of engineers gathered around a newly arrived machine—an M4A1 Sherman, captured intact in North Africa and shipped home for study. Its olive paint was still scorched from the desert, its tracks worn and dented, but the tank itself was a treasure trove of enemy engineering.

A white placard hung on the side of the hull: U.S. Panzerkampfwagen Type M4.

Oberingenieur Klaus Mittner, a senior technician from Henschel—the company behind the Tiger—walked slowly around the vehicle, clipboard in hand. He squinted through the smoke curling from his cigarette. The tank looked crude to him, almost primitive. The weld seams were uneven. The armor plates looked thin, even soft. The cast turret seemed almost lumpy compared to the sleek geometry of a Panther’s sloped armor.

He exhaled sharply. “Rough. Inelegant. Typical.”

But as his team began to dismantle the Sherman piece by piece, that sense of superiority began to falter.

The first surprise came when they lifted the rear engine hatch. Beneath it sat a Continental R975—a radial, air-cooled, nine-cylinder engine originally designed for aircraft. The men stared at it, puzzled.

Mittner frowned. “An airplane engine? In a tank?” He shook his head. “Madness.”

A mechanic twisted the ignition. The engine roared to life instantly, filling the hangar with a steady, throaty growl. No coolant lines. No complicated piping. Just simple, efficient machinery.

A young assistant shouted above the noise, “It starts easier than a Panzer III!”

Mittner didn’t respond. He was staring at the engine mounts—each one numbered, each bolt labeled. The brackets, hoses, and even the spark plug wires bore stamped codes. Every single component had a place and a purpose, designed for quick replacement.

He wrote quietly on his clipboard: Maintenance simplified. Standardized fittings. Field repair possible.

Later, as the team disassembled the gearbox, another revelation came. One engineer held up a cast transmission housing and compared it to the one they had studied months earlier from a different captured Sherman. He froze.

“The serial numbers,” he said. “They match.”

Mittner looked up. “Match?”

“Not just the numbers, sir. The dimensions. Every thread, every bolt pattern—it’s identical. They’re interchangeable.”

The hangar fell silent except for the dripping of oil onto the concrete.

Interchangeability.

For German engineers accustomed to hand-fitting parts, to fine-tuning tolerances with micrometers, the concept was almost alien. Their tanks were unique works of craftsmanship—each one requiring hours of skilled labor, each one slightly different from the next. The idea that an army could swap a gearbox from one tank to another without adjustment defied everything they believed about engineering.

By afternoon, they moved to the radio compartment. Inside, they found a complete communications system—an SCR-508 long-range transmitter. Every Sherman, even the most basic variant, carried one.

A young technician muttered, “They put radios in every tank?”

Mittner nodded slowly. “Every one.”

In the German army, only command tanks were equipped with radios. Communication in battle relied on hand signals, flares, or sheer guesswork. But here was a tank built to talk—to coordinate, to adapt, to fight as part of something larger.

“They must have thousands of these,” one engineer said.

Mittner looked at him and answered quietly, “Tens of thousands.”

As the night wore on, the dismantling continued. The team discovered that the Sherman’s tracks, though lighter and thinner than a Panther’s, could be replaced in under an hour. Its suspension system, simple vertical volute springs instead of complex torsion bars, could be repaired in the field with nothing more than a wrench and brute strength. Its hatches were oversized, designed to let crews escape quickly.

By morning, the floor of the hangar was littered with neatly labeled trays—drive sprockets, suspension arms, gearboxes, bolts, each tagged and arranged. The Sherman had been reduced to parts. Yet, instead of revealing weakness, it revealed something far more unsettling.

It wasn’t designed for beauty or even superiority. It was designed for endurance. For speed. For replacement.

Mittner stood over the stripped hull, his clipboard heavy with notes. His pen hovered for a moment before he wrote the final line of his preliminary report:

Armor: inferior to German rolled plate, but consistent and reliable. Engine: air-cooled, highly dependable, low maintenance. Internal design: simplified for operation by personnel with minimal technical experience.

He hesitated before adding one last observation—a sentence that seemed to defy everything he had been taught about engineering.

Then, almost reluctantly, he wrote it down.

Continue below

August 1942, North Africa. Under the burning sun near Elammagne, a strange silhouette sat half buried in the sand. A knocked out American M4 Sherman, its hull scorched but still recognizable. Around it stood a group of German officers and engineers from the Africa Corps. Their tan uniforms covered in dust.

They circled the wreck, measuring the armor with calipers, tapping the steel with gloved knuckles, muttering to each other in disbelief. “This is what the Americans send to war,” one of them sneered. “Too tall, too thin, too simple. It’s a toy, not a tank.” Laughter rippled across the group. To men who built and worshiped machines like the Panzer 4 and the Tiger, this foreign machine looked absurd, an ungainainely box on tracks almost civilian in its proportions.

Yet the same laughter echoed in research centers across Europe. When the first Shermans appeared on the battlefield, the German press mocked them as mobile coffins. Panzer commanders saw them as easy prey. The idea that this clumsylooking tank could challenge the legendary Tigers seemed ridiculous, but warlike industry hides its truths beneath the surface.

As the desert wind blew fine sand into the tank’s open hatches, one of the German engineers bent down and examined the interior. He frowned. The controls were surprisingly simple. The transmission levers, the gauges, the radio, everything was clear, standardized, almost intuitive. No intricate gear system, no custommade parts, just functional design.

He scribbled a note in his log book. Interesting mass-roduced layout, resembles civilian automotive style. He didn’t realize it yet, but those words hinted at the secret that would decide the war. In Berlin, military command remained confident. German tanks were masterpieces, handcrafted, powerful, meticulously engineered.

A Tiger I weighed twice as much as this American machine, and could destroy it from a mile away. But what no one in that room could see was that the true battlefield wasn’t made of sand or steel. It was made of assembly lines. At the time of Elamine, the United States had been at war for less than a year. Yet already its factories were transforming from car production to total war output.

Ford, Chrysler, General Motors, names that once built sedans and trucks were now turning out tanks, engines, and spare parts at an unimaginable scale. Every Sherman looked the same because it was the same. Every bolt, every track link, every control lever could be swapped with another built thousands of miles away.

The German engineers staring at that wreck didn’t yet understand what that meant. They saw weakness where there was genius and simplicity where there was power. One American soldier later recalled, “They built tigers like jewelry. We built Shermans like hammers.” The difference was philosophical, not mechanical. Germany believed perfection would win wars.

America believed production would. And in the long run, production always outlives perfection. As night fell over the desert, a sandstorm began to rise. The wrecked Sherman stood like a silent witness to a coming truth that the future of warfare belonged not to the strongest machine, but to the system that could build repair and replace it faster than the enemy could destroy it.

If you believe victory belongs to the side with the most powerful tank type one in the comments, but if you believe victory belongs to the side that can build faster than it breaks, hit the like button. Either way, this story will make you rethink what real power looked like in World War II.

Winter 1943, Kumerdorf, proving ground south of Berlin. In a vast hanger that smelled of oil, iron, and cigarette smoke, a group of engineers gathered around a captured M4A1 Sherman tank freshly shipped from North Africa. Its olive drab paint was still scorched by the desert sun, its tracks dented, but the tank was largely intact, a priceless specimen for the German armament’s office.

A placard marked it simply, US Panzer Compwagon type M4. Flood lights illuminated the machine as Oberg engineer Klaus Mitner, a senior engineer from Henchel, approached it with a clipboard in hand. To him it looked crude, almost agricultural. The welds seemed rough, the armor flat and unsophisticated the cast turret almost primitive compared to the angular precision of a Panther or Tiger.

Yet, as his team began to take the tank apart piece by piece, that arrogance began to dissolve. The first surprise came when they lifted the engine deck. Beneath it sat a Continental R975, an air cooled radial engine originally designed for aircraft. Mitner frowned. An airplane engine in a tank madness, he thought.

But when the team started it up, the engine roared to life immediately, smooth and steady. No coolant leaks, no complex piping, no delays. The simplicity was startling. hair overengineer a young assistant shouted above the noise it starts easier than a panzer 3 mitner didn’t answer he was staring at the engine mount each bolt each bracket each line was numbered even the spark plug wires were labeled every component was designed to be replaced quickly even by unskilled mechanics when they disassembled the gearbox another discovery stopped them cold the transmission housing bore a

cast number identical to the one on and another captured tank examined months earlier in Italy. Identical dimensions, identical threads, identical tolerances. Mitner turned to his assistant. That means the young man finished his sentence softly. They’re interchangeable.

For a moment, the hanger went silent, except for the dripping of oil from the disassembled hull. The Germans, accustomed to hand fitted parts and custom machining, were looking at something entirely different. A tank built like a car, not a masterpiece, but a product. Later that afternoon, they opened the radio compartment. To their astonishment, every Sherman came equipped with a standardized long range transmitter, the SCR508.

For the German army radios were a luxury. Only command tanks had them. here. Even the lowest ranked tank commander could communicate instantly. One technician muttered. They must have thousands of these. Mitner corrected him quietly. Tens of thousands. As the engineers worked through the night, they noted more details that defied German logic.

The Sherman’s tracks were lighter than those on a Panther, but far easier to remove. Its suspension based on vertical volute springs looked almost comical. simple coils instead of complex torsion bars, but each unit could be replaced in under an hour. Its hatches were oversized for fast evacuation.

Its interior layout designed for crew comfort and efficiency rather than perfection of form. By morning, the floor of the hanger was littered with labeled components, suspension arms, drive, sprockets, gearboxes, bolts arranged neatly in trays. An American tank reduced to its anatomy. And yet the picture it revealed was unsettling. The Germans realized the Sherman wasn’t designed for excellence. It was designed for speed repair and replacement.

Mitner began dictating his report. Armor 51 mm frontal sloped steel composition inferior to our rolled plate, but consistency remarkable. Engine air cooled reliable maintenance minimal internal arrangements simplified for operation by personnel of limited technical experience. He hesitated before adding one final sentence.

Production method indicative of large-scale automotive adaptation. That line more than the tank itself terrified him. Germany’s war industry was still built around craftsmanship factories specializing in one component technicians laboring for weeks on a single turret. In America, car factories had been converted into tank plants. Conveyor belts replaced artisans.

Each part of this Sherman was evidence of a civilization that had learned to make complexity vanish behind simplicity. When Mitner presented his preliminary findings to his superior Ober Ernst Richter, the colonel listened silently, his face unreadable. Then he asked one question.

Can we copy it? Mitner looked down. Not exactly. We could build one, yes, but we cannot build 10,000 of them. Not with our tools, not with our workforce. Not while the bombers are above us. That night, Mitner sat alone in his quarters, staring at a small piece of the tank he had kept a stamped American bolt perfectly machined identical to thousands of others he would never see.

He turned it in his fingers, marveling at the precision, the ease, the confidence it represented. In that simple piece of steel, he saw a truth no general wanted to admit. The Americans weren’t winning through strength. They were winning through standardization.

If you believe that the true weapon of World War II wasn’t the gun or the tank, but the factory type one in the comments. If not, hit the like button. I want to know what you think defines power in a modern war. In the early months of 1944, as the Allies prepared for the invasion of Europe, the Sherman had already earned a strange reputation among both its crews and its enemies. To American tankers, it was the Ronson lights.

every time a dark joke about its tendency to catch fire when hit. To the Germans, it was simply, “Dear Tommy Cocker, the Tommy Cooker.” They mocked it in propaganda leaflets, claiming a single Tiger could destroy a dozen Shermans before the first American gunner even found his range.

But what the Germans didn’t realize was that the Sherman’s secret strength wasn’t its armor, nor its gun, nor even the men inside it. Its real power came from the fact that it was never designed to be immortal. It was designed to die and be replaced endlessly. At the Detroit tank arsenal, massive factory doors opened every morning to the thunder of machines.

Conveyor belts rolled like veins of steel carrying unfinished hulls through clouds of sparks and sweat. Women in overalls welded armor plates. Teenagers tightened bolts. A new Sherman emerged every 56 minutes. One historian later wrote, “America didn’t build tanks. It built the idea that tanks could never run out.” By 1944, 11 factories across the United States were producing the M4 in different configurations.

Welded hulls, cast holes, diesel or gasoline engines, wide or narrow tracks, and yet every single one of them could share parts. A final drive from a Lima built Sherman would fit perfectly into a Fiserbuilt hull. A turret cast in Grand Blunk, Michigan could sit on a chassis assembled in California. It was modular warfare decades ahead of its time.

In contrast, every German tank was practically handmade. The Tiger I required 300,000 labor hours to build. A Panther needed 150,000. the Sherman less than 50,000 and with a fraction of the specialized tooling. Where the Tiger demanded obsessive precision and weeks of test fitting, the Sherman demanded only repetition. Its tolerances were broader, its design forgiving.

The Germans saw this as proof of inferiority. In truth, it was genius. American engineers understood something their enemies did not. that war consumes machines faster than perfection can produce them. The Sherman’s components reflected this philosophy. Its vertical volu suspension, mocked by German designers as archaic, could be repaired in the field with a crowbar and an hour of daylight.

The Tiger’s complex interleved road wheels designed for superior traction clogged with mud and froze in winter. Sherman crews carried spare track links on the hull sides. They could swap them mid combat. The M4’s air cooled radial engine, once criticized as primitive, kept running in conditions that stalled Germany’s liquid cooled Maybox. Every decision, every simplification was a sacrifice of elegance for endurance.

In a technical sense, the Sherman was not a better tank. It was a better idea of a tank. It wasn’t built to dominate a single duel. It was built to survive a long war. The German command boasted that one Tiger could destroy five Shermans. Statistically, they were right. But America could replace those five tanks in less time than Germany could repair one Tiger.

And when the sixth Sherman arrived and then the seventh, the mathematics of war turned inevitable. This industrial rhythm extended even to logistics. Each Sherman came with tool kits standardized across the army. Replacement engines arrived precrded. Entire drivetrains could be swapped in less than a day. Mechanics didn’t need master craftsmen. They needed only instructions and a wrench.

One maintenance officer in Normandy recalled, “We could rebuild a Sherman with the parts from three damaged ones before sunset. That was the logic of attrition turned into art. the brutal poetry of total war. German engineers knew this truth, but were powerless to act. Allied bombing crippled their factories, forced production underground, fragmented supply lines.

Each Tiger or Panther rolled out of the assembly hall like a sculpture perfect but doomed. Every destroyed Sherman, meanwhile, was a seed that multiplied. By mid 1944, the United States was producing 2,000 Shermans per month, more than the entire German output of all tank types combined. The Reich was trapped in a race it had already lost.

When German intelligence officers examined Sherman recovery reports, they were stunned. A single tank might be written off, but its components, engine blocks, gearboxes, periscopes were harvested and reused. The Americans weren’t just building machines. They were recycling victory. They treated tanks as consumables, not icons.

A German colonel reviewing the data shook his head and said quietly, “They build them as if they expect them to die.” That was the point. The Sherman was expendable by design. It existed to keep moving forward, not to be preserved. Its simplicity made it eternal because it could be reborn faster than it could be destroyed. Perfection dies with its maker.

Simplicity survives because anyone can make it again. If you agree that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication in war type one in the comments if you think perfection should always be the goal hit like and tell us why. The next part of this story will show how Germany’s obsession with perfect machines became its fatal weakness. Spring 1944, Northern France.

In the stillness before dawn, the engines of a Tiger battalion growled like distant thunder. Each machine, 57 tons of steel powered by a precisionbuilt Maybach engine, represented the pride of German engineering. The crews believed they commanded the most powerful tanks in the world. And in a duel, they often did.

A Tiger’s 88 mm cannon could rip through a Sherman before the American gunner even fired. Its armor could shrug off direct hits that would have torn other tanks apart. But beneath that confidence, a different kind of fear had begun to spread, one measured not in caliber, but in numbers.

In the fields near Ver’s Boage, a veteran Tiger commander watched through binoculars as a formation of Sherman tanks advanced across the hedge. There weren’t five or 10 of them. There were dozens stretching across the valley like a moving wall. He ordered his gunner to open fire. The first shot destroyed the lead tank.

The second knocked out another, but as black smoke curled upward, more Shermans appeared behind them, then more after that, rolling forward relentlessly. They never stopped coming. One German gunner muttered, loading another round. By the time his ammunition rack was empty, the enemy still filled the horizon. That image, the endless wave, was what began to break the morale of even Germany’s best tank crews.

For years, propaganda had promised them technological superiority. One German tank is worth 10 American ones, the posters boasted. But by mid 1944, the math no longer worked. Every Tiger loss was a disaster requiring months of replacement time. Every Sherman loss was an inconvenience replaced within days.

At the height of the Normandy campaign, American factories produced nearly 2,500 tanks a month. The entire German war industry managed fewer than 500. On paper, the Tiger remained the deadliest tank in Europe. In reality, it was being buried under an avalanche of steel. In field reports from the second SS Panzer Division, officers began noting a strange pattern. battles they won no longer mattered.

Even after destroying dozens of Shermans, they found themselves retreating a week later, not because they’d been defeated tactically, but because the Americans had already replaced every tank they’d lost. A Tiger Ace named Otto Cararius later wrote in his memoirs, “For every Sherman we destroyed, three more appeared. You could destroy machines, but not the factories that birthed them.” The difference was philosophical. German design celebrated perfection.

Every component of a Tiger was built by hand, fitted by specialists, tested individually. It was an object of pride. The Americans treated their tanks like tools, imperfect, but available, standardized, repable, replaceable. The Tiger’s power was absolute, but fragile.

One broken gearbox could immobilize it for weeks. A Sherman’s gearbox could be replaced in an afternoon. In Berlin, the Ministry of Armaments received reports warning that the obsession with complexity was strangling production. Albert Spear, Hitler’s armaments minister, pleaded with design bureaus to simplify. He wrote, “Our tanks are masterpieces, but masterpieces are slow.” Hitler refused.

To him, quality was a matter of prestige. Quantity is the refuge of the weak, he said in one meeting. The irony was bitter. That statement doomed the Reich’s armored core. On the front lines, German mechanics faced a different kind of despair. Spare parts were scarce, and even compatible components between tank models were rare.

A Tiger crew might strip a damaged vehicle for pieces only to find the fittings didn’t match. In contrast, American mechanics in Normandy’s hedge rows worked like surgeons on a production line engines, swapped tracks, replaced radios, recalibrated, and the tank sent back into combat within 24 hours. Every destroyed Sherman returned as a new one reborn from the system that made it.

By late summer, even frontline officers understood the truth. Captain Hinrich Lurser of the Ponzer Lair Division wrote in a private letter, “Our tanks are magnificent, but what good is magnificence when the enemy never runs out. Their factories are as lethal as their guns.” The myth of German invincibility was dying not from a single battle, but from arithmetic.

In one of his final reports before the Allied breakout from Normandy, a disillusioned German colonel wrote, “We are fighting against an economy, not an army. We can destroy their tanks, their planes, their men, but not the rhythm that replaces them.” His words captured the essence of the delusion that had defined Germany’s war.

The Reich believed it could outthink, outbuild, and outfight a nation whose greatest weapon was organization itself. As the Allies advanced eastward, the rerecks of German armor lined the road silent monuments to a philosophy that confused perfection for power.

Those who survived began to realize the crulest truth of all in a war of machines art dies quickly. Only mass production endures. if you’ve ever believed that perfection guarantees survival type one in the comments. But if you think adaptability and scale win every long war hit like and tell us why. The next part will take you behind the assembly lines that made this possible where America’s factories turned democracy itself into a weapon.

Detroit 1943. The air smelled of oil, steel, and coffee. Inside the Ford River Rouge, plant sparks rained from overhead cranes as hulls of unfinished Sherman tanks rolled down tracks where Model T’s once had. The clanging of rivets, the thunder of hydraulic presses, and the rhythmic hiss of welding torches merged into a mechanical symphony that never stopped.

The United States had transformed its industrial heart into an arsenal unlike anything the world had seen. The same nation that once built cars for families was now building freedom in steel. Henry Ford’s factories were only part of it. Across the Midwest, a civilization of machinery had come alive.

Cleveland built engines. Chicago built transmissions. Pittsburgh poured the steel. California assembled the final tanks for Pacific duty. Even in small towns, machine shops worked around the clock machining bearings, gun mounts, and armor plates. By the end of 1943, the United States had mobilized 18 million workers for war production.

Nearly onethird of its entire labor force. 2 million of them were women. They welded seams, cut steel, inspected gears, and tested engines that roared like thunder through factory hangers. The posters called them Rosie the Riveters. But to the men at the front, they were invisible allies who replaced despair with reinforcements.

At the Chrysler tank arsenal in Warren, Michigan, the process was pure choreography. A tank entered the line as a skeleton of steel. 90 minutes later, it rolled out of the far end under its own power. In February 1943 alone, the plant produced 100 Shermans, more than Germany could produce of all armored vehicles that month combined. Workers painted messages on the halls before shipping them overseas. For Berlin, for the boys, keep rolling.

It wasn’t just production. It was conviction cast in metal. What made it possible was the genius of standardization. Every American factory used the same blueprints, the same part, numbers, the same specifications. A mechanic in Normandy could open a crate from Detroit, replace a gearbox, and the tank would move again without adjustment.

The Reich’s engineers, still working with bespoke craftsmanship, were trapped in a labyrinth of their own perfection. The Americans had turned simplification into strategy. On the floor of the Ford plant, managers installed clock systems that tracked every stage of production, welding, riveting, assembly testing. If one line slowed, another picked up the slack. Nothing stopped.

Even maintenance crews worked in shifts to repair machines while production continued. One engineer recalled, “We ran for 30 months without a single day’s pause. The result was staggering. By mid 1944, the US was producing one Sherman every 30 minutes. To supply that machine empire, America min smelted refined and transported resources on a scale the Axis could not comprehend.

The Great Lakes carried 80 million tons of iron ore to the furnaces of Pennsylvania and Ohio. Railroad networks moved 10,000 tank engines a month. Freight ships delivered steel to shipyards and aircraft plants simultaneously. It was an orchestra of logistics where every factory played its part in perfect time. In Washington, Franklin Roosevelt called it the arsenal of democracy.

But to the Germans who read intelligence reports, it looked like an industrial nightmare made real. In one declassified report captured in 1945, a Vermach analyst wrote, “The Americans produce as if machines themselves were alive. Their factories do not rest and their output is beyond calculation. At the same time, the United States had solved another problem Germany never could maintenance in motion.

Field depots shipped spare parts in standardized crates labeled with pictograms so soldiers could identify them without reading. Mobile repair units followed divisions across Europe. One truck carried engines, another transmissions, another welding equipment. Every damaged tank was a temporary problem, not a permanent loss. In contrast, Germany’s armored core had towroken tanks hundreds of miles back to factories already under bombardment. The contrast went deeper than material.

It was philosophical. America’s war production wasn’t just about building things. It was about building systems. The Tiger might have been stronger, but its strength lived and died with each tank. The Sherman was a node in a network replaceable, predictable, infinitely reproducible. The US didn’t build weapons.

It built the means to build weapons. And that changed the rules of war forever. On the factory floor, a supervisor named Helen Walker wiped sweat from her forehead as the latest Sherman rolled off the line. The siren sounded a signal of completion.

Hundreds of workers paused for a moment to watch the machine move under its own power for the first time. Someone began to sing, “God Bless America.” The rest joined in. It wasn’t ceremony. It was momentum. Every tank shipped out that day meant one more crew in Europe that wouldn’t have to fight empty-handed.

Meanwhile, in Germany, engineers studied captured American production manuals, trying to understand how such consistency was possible. One noted bitterly, “They have engineers designing machines. We have artists designing monuments.” He wasn’t wrong. “The American assembly line was democracy made mechanical, flawed, noisy, but unstoppable.

” By the summer of 1944, as the Allies landed in Normandy, the output of those factories flooded the European continent. Rows of Sherman tanks rolled off transport ships and across French soil identical as twins, their engines humming in unison. For every tank lost, two more arrived. For every destroyed bridge, an engineer battalion built another.

Germany was still fighting battles. America was fighting with logistics. If you believe that power lies not in genius but in organization type one in the comments. If you think creativity can still defeat the machine hit like I want to hear your thoughts. Autumn 1944 the Reich was burning from Hamburg to Munich. The night skies glowed orange with the light of Allied bombers.

Factories that once echoed with the hum of machines now smoldered in silence. Inside a bunker outside Berlin, a group of senior engineers and officers gathered around a wooden table. Among them was Ober engineer Hinesk Knipamp. One of the men responsible for the Tiger and Panther designs, the pride of German engineering.

On the table lay the latest intelligence reports from the front. What he read that night would stay with him for the rest of his life. The first report came from Normandy. American forces had landed in June with more than 4,000 tanks. By August, despite losing hundreds, their total number had increased. Nip camp read the line twice, thinking it a misprint.

They lost, and yet they have more, he whispered. A logistics officer confirmed it. Replacement divisions were arriving faster than German units could retreat. New Shermans fresh from American factories rolled off landing craft daily. They fight one war here, the officer said quietly while building another one at home.

Nipcamp leaned back in his chair, the air thick with the smell of smoke and coffee gone cold. Around him his colleagues argued in low, tired voices. One blamed the bombings. Another blamed Hitler’s obsession with miracle weapons. But deep down, every man in that room knew the truth. Germany was not losing to better tactics or braver soldiers. It was losing to arithmetic.

Later that evening, Nipamp turned to his assistant, a young engineer named Deer, and handed him a folder. This is a production analysis, he said. Inside were tables comparing monthly tank output. Germany 600 Panthers, 150 Tigers. The United States 2 by 500 Shermans. Why 500 tank destroyers, 5,000 aircraft? Look at this, he murmured.

They are making engines faster than we can make bolts. Deer didn’t answer. The numbers spoke for themselves. In another part of Berlin, Albert Shar, the Reich Minister of Armaments, was having his own moment of reckoning.

His intelligence officers had just delivered a captured American War Department report titled Production Statistics of US Armored Vehicles. It detailed the output of every American factory Ford’s Michigan plant, General Motors Cleveland Works Chrysler’s Warren Arsenal. At the bottom of the page, one figure stood out. Total M4 Sherman tanks produced by 1944, $40,000. Spear set the paper down and said quietly, “This is no longer war. This is slaughter by industry.

” He wrote in his personal diary that week, “We were craftsmen fighting an engineer civilization. Every time we made something perfect, they made 10 things good enough.” For the first time, the man who had organized Germany’s industrial might, admitted that the enemy system, not his genius, would decide the war.

At Kumerdorf, the same facility where engineers had once dismantled the captured Sherman, the last surviving technicians now dismantled their own work. Panther hulls lay half-finished under tarpollins. Supply trucks sat idle for lack of fuel. One mechanic joked bitterly, “We should start building wagons. At least they don’t need gasoline.” No one laughed.

The sound of distant artillery reminded them how close the front had come. Nipamp spent that winter drafting an internal memo he would never send. In it, he described the lessons he believed Germany had ignored. We worshiped perfection. The Americans worshiped process. They could afford to fail because they could rebuild. We could not.

He wrote about the Tiger’s complexity, how a single broken track could immobilize a unit for days, and compared it to the Sherman’s crude but functional design. They designed for the average mechanic. We designed for gods. By early 1945, even Hitler’s inner circle had begun to grasp the scale of the disaster.

When Spear presented his production data in January, Hitler dismissed it as defeist propaganda. Our new jet fighters will reverse everything he declared. Spear didn’t argue. He simply folded the papers and walked out. He knew the truth. No amount of innovation could compensate for a nation running out of oil, steel, and time. In March, a report from the front described a battle near Remigan.

A Tiger 2, one of Germany’s most formidable tanks, destroyed 12 Shermans before being hit. The crew survived, but the tank threw a track during retreat and had to be abandoned. When American engineers examined it, they noted the exquisite machining of its components. Each gear and bolt polished to perfection. One wrote in awe, “It’s beautiful, but impossible to massproduce.” The irony was complete.

The very perfection that had once symbolized German strength had become its weakness. As the Allies crossed the Rine, Ganipamp stood in the ruins of his office, flipping through a final report. The Reich had produced just under 50,000 tanks during the entire war. America had produced over $88,000 and Britain and the Soviet Union, tens of thousands more.

“We have been overtaken by mathematics,” he said softly. That night he walked outside. In the distance, he could hear the faint rumble of artillery, and beneath it, something else, the endless drone of engines, American trucks, tanks, and planes, thousands of them, moving as one mechanical tide. He realized then that it wasn’t just Germany that had lost.

It was the old world itself. The age of craftsmanship had died under the weight of mass production. If you believe that perfection is fragile and that resilience wins wars, type one in the comments. If you think mastery can still defeat the machine hit, like I want to hear your thoughts. May 1945, the guns of Europe had fallen silent across the shattered cities of Germany.

The air still carried the metallic scent of smoke and defeat. Columns of captured tanks stood motionless along the roads. broken tigers and panthers. Their engines seized their tracks torn. Nearby, American Shermans rolled past dusty, but alive, their engines coughing steady rhythm in the dawn light.

The war that had begun with laughter at a clumsy American tank had ended with that same machine parked in the heart of Berlin. In the days that followed, Allied engineers toured what remained of Germany’s war industry. Inside bombedout factories, they found precision tools buried in rubble, incomplete blueprints for new tanks and the wreckage of a system that had tried to outthink the world but could not outproduce it.

One American officer wrote home, “Their machines were brilliant, but they never understood the power of a factory that never sleeps.” At an interrogation center near Agsburg, Hines Kipkamp sat across from a US technical intelligence officer. The young American laid a single bolt from a Sherman tank on the table and asked, “Could Germany have made this nip comp, turned it in his hand, studying the clean threads and uniform machining.” “Of course,” he replied. “We could make one.

” The officer smiled. “We made a million.” Nipcamp placed the bolt back down and nodded slowly. Then you’ve already won twice. First on the battlefield and then in the factory. In Washington months later, an American engineer gave a lecture on wartime production. On the screen behind him appeared two silhouettes, the Tiger and the Sherman. He pointed to the Tiger.

This was the masterpiece, he said. Precision, complexity, power. Then he pointed to the Sherman. This was the idea. Simple, repable, repeatable. We didn’t build tanks. We built a system that could replace them faster than they could be destroyed.

That philosophy, the belief that power comes not from perfection, but from adaptability, had defined the outcome of the war. Germany’s engineers had pursued immortality through design. America’s engineers pursued endurance through replication. One created legends, the other created history. Today, a single surviving Sherman stands in a museum in Bastonia. Its armor scarred its paint faded by time.

Visitors walk around it quietly, reading the plaque beneath its tracks, mass- prodduced for freedom. Few realize that the story of that tank is not about metal or machinery, but about mindset. The understanding that survival belongs not to the flawless, but to the flexible. When German engineers dissected their first captured Sherman, they believed they were examining an inferior enemy.

What they were really dissecting was a mirror of their own future. A future where innovation would no longer be measured by the brilliance of a single design, but by the scale of an entire system. The Tiger was the last great monument of the artisan age. The Sherman was the herald of the industrial one.

For the men who fought inside them, neither machine was perfect. To the German crews, the Tiger felt invincible until it broke down. To the American crews, the Sherman felt expendable until it saved their lives. Both machines demanded courage, and both became legends. But when history counted the cost, it wasn’t courage that decided victory. It was capacity.

As dusk falls over the museum floor, the Sherman’s olive hull catches the last trace of light. In that glow lies the silent lesson of a century, that strength is not the absence of weakness, but the ability to recover faster than you fall.

News

CH2 How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea

How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea January 16th, 1943. The morning…

CH2 How One Pilot’s “Forbidden” Flap Setting Made Thunderbolts Climb Faster Than Fw 190s

How One Pilot’s “Forbidden” Flap Setting Made Thunderbolts Climb Faster Than Fw 190s The morning of March 15th, 1944,…

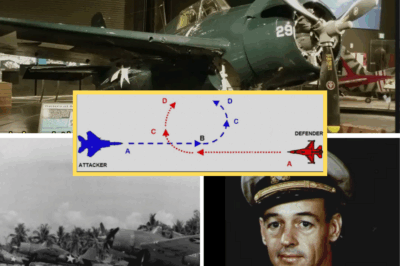

CH2 How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly

How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly The morning sky above Wake Island…

CH2 Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky The air above Rapopo…

CH2 Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons

Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons At 6:15 on…

CH2 What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History

What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History In the spring…

End of content

No more pages to load