Did American Showers Really Become a DEATH S3NTENCE for German POWs?

In May 1945. A pine forest outside Schwerin, Germany. A group of terrified Nazi women waited among the trees. They had burned their records—fed their ledgers and diaries into the fire—and braced for capture, for humiliation, for torture. Instead, the Americans handed them… soap. The war had ended not with a bang, but with a profound and unsettling silence.

Across the shattered continent of Europe, the air—once thick with the chords of artillery and the drone of bomber fleets—now hung heavy with a different kind of weight. It was the dust of absolute finality, the stillness of a great and terrible machine that had finally run out of fuel, parts, and men. For the soldiers of the victorious Allied armies, it was a moment of bone‑deep exhaustion and triumphant relief.

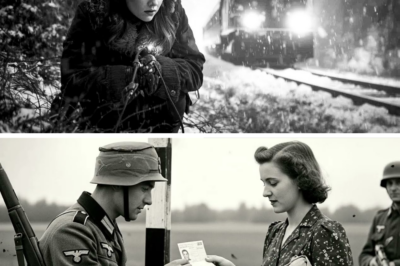

But for the hundreds of thousands who had served the collapsed German regime—the cogs of the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, and their myriad support structures—the cessation of fighting simply ushered in the dreadful, agonizing wait for the reckoning. The war was over, but the anxiety was only just beginning. Among these were thousands of young women, many barely out of their teens.

They were the Wehrmachthelferinnen and Luftwaffehelferinnen, the female auxiliaries who formed the administrative and communicative sinew of the Nazi war machine. They were the daughters of the Reich, raised in the crucible of the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the League of German Girls, where they had been taught that their highest calling was service and sacrifice to the Führer and the Fatherland.

Their battlefields had been the telephone switchboard and the typewriter, their weapons the telegraph key and the stenographer’s pen. They had routed commands through collapsing networks, guided bombers through the dark with precise radio triangulations, and tallied the grim arithmetic of a lost cause. Though they did not carry rifles, they were uniformed, disciplined, and fiercely loyal to a state that had been the sole architect of their worldview.

In a pine forest outside Schwerin, the end took on the scent of gunpowder and burning paper. Here, a group of young Helferinnen performed their last official act. They fed the remnants of their service into a crackling bonfire: ledgers filled with meticulous records, transmission logs containing the ghosts of final orders, and personnel files that were the only proof that certain men had ever existed.

Some tossed in their own diaries and letters, a desperate attempt to erase their personal history before the enemy could read it. The paper curled into black flakes, dancing in the spring air like morbid confetti—a funeral for a world. Each flicker of the flames illuminated the faces of the true believers, their jaws set in brittle defiance, and the faces of the terrified, their eyes wide with the apprehension of what was to come.

Their terror was a carefully constructed masterpiece, the pièce de résistance of Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda ministry. For years, they had been fed a constant diet of heroic sacrifice and absolute, unforgiving ideology. They had been shown newsreels and posters depicting the Americans not as soldiers, but as leering, gum-chewing gangsters; jazz-obsessed degenerates from a cultureless, racially mixed land, controlled by Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracies. They were warned of the Morgenthau Plan,

a supposed Allied plot to de-industrialize Germany and condemn its people to a permanent agrarian peasantry. They had seen the skeletal ruins of Hamburg and Dresden and internalized the logic that their captors would treat them as they believed Germany would have treated its own conquered foes.

Continue below

In May 1945. A pine forest outside Schwerin, Germany. A group of terrified Nazi women waited among the trees. They had burned their records—fed their ledgers and diaries into the fire—and braced for capture, for humiliation, for torture. Instead, the Americans handed them… soap. The war had ended not with a bang, but with a profound and unsettling silence.

Across the shattered continent of Europe, the air—once thick with the chords of artillery and the drone of bomber fleets—now hung heavy with a different kind of weight. It was the dust of absolute finality, the stillness of a great and terrible machine that had finally run out of fuel, parts, and men. For the soldiers of the victorious Allied armies, it was a moment of bone‑deep exhaustion and triumphant relief.

But for the hundreds of thousands who had served the collapsed German regime—the cogs of the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, and their myriad support structures—the cessation of fighting simply ushered in the dreadful, agonizing wait for the reckoning. The war was over, but the anxiety was only just beginning. Among these were thousands of young women, many barely out of their teens.

They were the Wehrmachthelferinnen and Luftwaffehelferinnen, the female auxiliaries who formed the administrative and communicative sinew of the Nazi war machine. They were the daughters of the Reich, raised in the crucible of the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the League of German Girls, where they had been taught that their highest calling was service and sacrifice to the Führer and the Fatherland.

Their battlefields had been the telephone switchboard and the typewriter, their weapons the telegraph key and the stenographer’s pen. They had routed commands through collapsing networks, guided bombers through the dark with precise radio triangulations, and tallied the grim arithmetic of a lost cause. Though they did not carry rifles, they were uniformed, disciplined, and fiercely loyal to a state that had been the sole architect of their worldview.

In a pine forest outside Schwerin, the end took on the scent of gunpowder and burning paper. Here, a group of young Helferinnen performed their last official act. They fed the remnants of their service into a crackling bonfire: ledgers filled with meticulous records, transmission logs containing the ghosts of final orders, and personnel files that were the only proof that certain men had ever existed.

Some tossed in their own diaries and letters, a desperate attempt to erase their personal history before the enemy could read it. The paper curled into black flakes, dancing in the spring air like morbid confetti—a funeral for a world. Each flicker of the flames illuminated the faces of the true believers, their jaws set in brittle defiance, and the faces of the terrified, their eyes wide with the apprehension of what was to come.

Their terror was a carefully constructed masterpiece, the pièce de résistance of Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda ministry. For years, they had been fed a constant diet of heroic sacrifice and absolute, unforgiving ideology. They had been shown newsreels and posters depicting the Americans not as soldiers, but as leering, gum-chewing gangsters; jazz-obsessed degenerates from a cultureless, racially mixed land, controlled by Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracies. They were warned of the Morgenthau Plan,

a supposed Allied plot to de-industrialize Germany and condemn its people to a permanent agrarian peasantry. They had seen the skeletal ruins of Hamburg and Dresden and internalized the logic that their captors would treat them as they believed Germany would have treated its own conquered foes.

They understood that in total war, the defeated surrendered their dignity first. They prepared their minds for the worst kind of prison: cold, filthy, starved, and filled with the malicious, triumphant cruelty of an enemy they had been taught was subhuman. The snapping of a twig in the undergrowth cut through the crackle of the fire. The world went silent.

From the deep green shadows of the forest emerged figures in unfamiliar olive drab, their helmets a different, rounder shape, their M1 rifles held with a casual exhaustion that was more intimidating than any overt aggression. They were not the snarling demons from the posters. They were young men, impossibly tall and well-fed, their faces caked in the dirt of a long and brutal campaign.

An American officer, his German accented but clear, gave a simple command: “The war is over for you. Drop your bags.” There was no immediate violence, no vengeful explosion, but this only heightened the tension. The cruelty, they believed, was being saved for later, for the dark corners of the prisoner-of-war camps that awaited them. This small, unexpected lack of malice was the first tremor in the foundation of their beliefs, a confusing data point that did not fit the narrative of absolute barbarism.

The fate of these young women was now entirely in the hands of the enemy they had been conditioned to despise and dread. The journey into captivity was a descent into a new kind of hell, one defined not by fire and brimstone but by mud, canvas, and the cold, impersonal logic of a vast military bureaucracy. The German women were herded from the forest onto the back of canvas-topped GMC trucks, the workhorses of the Allied logistical miracle that had crushed their nation.

As the engines growled to life, they huddled together, a collection of secretaries and signalers, now prisoners of war. The journey was jarring, every lurch and bounce a physical reminder of their powerlessness. Through tears in the canvas, they caught glimpses of their defeated homeland, a landscape of apocalyptic ruin.

Cities were not cities anymore, but skeletal remains, gutted buildings gaping at a vacant sky like the sockets of a skull. The roads were choked with a slow, desperate migration of ghosts: columns of German soldiers marching with their hands on their heads, their faces a uniform mask of numb surrender; families pulling wooden carts piled high with their worldly possessions, fleeing the advancing Red Army in the east.

This was the Götterdämmerung their leaders had prophesied—the Twilight of the Gods—but it did not feel heroic. It felt hollow. It smelled of dust, decay, and the metallic tang of collective shame. After hours that felt like days, the trucks rumbled into a massive, sprawling complex of tents and barbed wire near Reims, in France.

The scale of it was staggering, a temporary city built of canvas, mud, and ruthless efficiency. This, they thought, is it. The Sammellager, the collection camp. The antechamber to their punishment. Their propaganda-fueled imaginations, honed by years of cinematic and radio-borne terror, filled in the horrifying details: interrogation cells where bright lights would burn their secrets out; torture racks designed to break their bodies and their spirits; vengeful commandants eager to make an example of them.

The canvas flap of the truck was thrown back, and the sudden daylight was a physical blow. The order came, “Raus! Schnell!”, but it was barked not by a snarling American, but by a German NCO, himself a prisoner, now tasked with marshaling his own defeated countrywomen. This was the first of many surreal inversions that would chip away at their sense of reality.

They were formed into lines, a river of gray uniforms flowing toward a series of processing tents, their minds braced for the expected degradation. The procedure, however, was methodical, impersonal, and utterly devoid of the sadism they had braced for. First came the delousing station. They were pushed into a tent and blasted with a fine white cloud of DDT powder, a humiliating but medically necessary indignity of mass confinement in the typhus-ridden landscape of 1945 Europe.

They expected jeers and crude remarks from the GIs administering the insecticide. Instead, the American medics, some of them women from the Women’s Army Corps, were professional, almost bored, their movements practiced and detached. There was no emotion in their faces—no anger, no pity, no contempt. It was the cold, clean logic of preventative medicine, a problem to be solved.

Next came the paperwork. One by one, they stood before a folding table where a GI with a Royal typewriter asked for their name, date of birth, and rank, his questions relayed by a translator. A number was stenciled onto the back of their tunic. They were photographed, holding a slate with their new identity: a string of digits. In this moment, they ceased to be individuals.

They were no longer Ursula Schmidt, the typist from Munich, or Lieselotte Meier, the radio operator from Kiel. They were inventory. This process of systematic dehumanization was something they understood intimately; their own regime had perfected it. But they had always been on the other side of the ledger. To be subjected to it was terrifying, yet the very bureaucracy of it felt strangely… safe.

It was not the passionate, personal hatred they feared. It was the dispassionate act of a global power managing a complex logistical problem. As they were led away from the processing tables, a corporal handed each woman a small, waxy cardboard box. A K-ration. Inside, they found crackers, a small tin of processed cheese, a fruit bar, a stick of chewing gum, and four cigarettes.

It was not a feast, but for women who had subsisted on black bread and watery turnip soup, it was a miracle of sustenance. They nibbled at the strange, salty crackers, staring at the unfamiliar packaging. This was the food of the enemy. It was not poisoned. It was simply… food. They had not been beaten. They had not been interrogated. They had been processed, deloused, fed, and numbered. The conqueror, it seemed, was not a beast. It was a machine.

In the chaotic aftermath of Germany’s surrender, the Allied high command faced a logistical nightmare of unprecedented scale. The sheer volume of surrendered personnel—millions of men and, unexpectedly, tens of thousands of female auxiliaries—threatened to overwhelm the already shattered infrastructure of Europe.

The continent was a landscape of displaced persons, food shortages, and simmering resentments. Housing and feeding this army of prisoners was a monumental task. For the male POWs, a network of camps was hastily established across France, Belgium, and Britain. But for the captured Helferinnen, a different solution was found.

A rapid, pragmatic decision was made: a significant number of them would be designated as Prisoners of War, processed, and shipped across the Atlantic, far from the deprivation and chaos, to large, organized camps in the United States. It was a decision born of military necessity, but for the women, it sealed their psychological terror. The rumors that had circulated in hushed German whispers in the Reims holding camp now solidified into a horrifying reality. They were going to America.

To the heart of the enemy’s land, to the continent they knew only through the distorted lens of propaganda. This journey felt like a final deportation, a one-way ticket to the promised land of their despair. They were moved by train from the muddy fields of Reims to the port of Le Havre. The city itself was a ruin, its medieval heart obliterated by Allied bombing, but its harbor was ferociously, terrifyingly alive.

It was a forest of steel masts and gray hulls, a testament to the colossal industrial might that had ground their own nation into the dust. Here, the sheer scale of the Allied war effort became sickeningly clear. They were not just defeated; they had been consumed by a power they could not even comprehend. They were marched up the gangplank of a ship that was not a luxury liner but a gray, functional American troop transport, the USS General John Pope.

As their feet left the soil of Europe, a profound sense of severance took hold. They were leaving behind not just a continent, but everything they had ever known. The gangplank was a bridge between two worlds, and there was no going back. Life at sea was a study in spartan order. The women were assigned to cavernous holds, their canvas bunks stacked four or five high in a dizzying vertical maze.

They were confined below deck for most of the day, a rolling, claustrophobic existence punctuated by the creak of the ship’s hull and the constant, low hum of the engines. For brief, glorious periods, they were allowed up onto the open deck to breathe the sharp, salt-laced air.

They would stand in silent, gray-clad groups, watching the endless, indifferent churn of the North Atlantic, an ocean that seemed as vast and empty as their future. The American guards, young GIs weary of war and eager to get home, were a constant but enigmatic presence. Their demeanor remained a puzzle. They were not cruel. They were not friendly.

They were professional, enforcing the rules with a detached efficiency that was more unnerving than open hostility. It was the same impersonal competence they had encountered during processing, a trait that seemed to be a defining characteristic of this strange new enemy. The food was still American, but now it was hot, served from a massive galley into their metal mess kits.

Stews thick with meat and vegetables, strong, bitter coffee, and sometimes a type of sweet, dense bread pudding. It was monotonous, but it was filling. It was sustenance without malice, another confusing piece of the puzzle. About a week into the voyage, a new order was issued, one that sent a ripple of primal fear through the crowded hold. They were to be taken in small groups to the ship’s showers.

Their minds, still deeply conditioned by years of propaganda and the now-circulating whispers of their own nation’s darkest secrets, leaped to the most terrifying conclusions. Deception. Humiliation. A trick. They thought of the stories, still unconfirmed but persistent, of the gas chambers their own regime had built, disguised as shower facilities.

Some of the women refused to move, weeping hysterically. Others went rigid with terror, their faces pale, their bodies trembling. But they were herded forward by the impassive WAC officers, their protests ignored, their terror dismissed. The room was not a chamber of horrors. It was filled with thick, billowing steam and the loud, steady hiss of water.

Pipes ran along the ceiling, fitted with a dozen simple shower heads. And on a wooden bench was a crate. Inside were dozens of small, plain, rectangular bars. Soap. An American female officer demonstrated through simple gestures. Turn the knob. Water comes out. Take the soap. Lather. Rinse. The first group of women watched, bewildered. Tentatively, one reached out and turned a handle.

Hot water—genuinely, gloriously hot water—cascaded down. A collective gasp went through the room. For most, it was the first hot, running water they had felt in years. In that hot spray, they scrubbed away weeks of grime, the dirt of the final, desperate battles, the filth of the crowded camps, the stink of fear. But they washed away something more.

The act was so simple, so fundamentally human, it defied all their expectations of vengeance. It was a kindness so profound in its simplicity that it felt like a weapon—one that dismantled their defenses more effectively than any interrogation ever could. The salt spray of the Atlantic gave way to the thick, humid air of the American coast. From the crowded deck of the USS General John Pope, the German women saw the shoreline of Virginia materialize through the morning haze.

It was not a landscape of industrial smokestacks or grim, gray fortresses as they might have imagined. It was green. Impossibly, luxuriantly, wantonly green. The sight was a profound shock, an assault of color on eyes accustomed to the gray and brown palette of a war-torn continent. They had been taught that America was a cultural wasteland, a concrete jungle of gangsters and skyscrapers.

But this was a place of sprawling forests and wide, open spaces, a land of vibrant, almost decadent life, utterly untouched by the physical scars of war. They docked at Newport News. The disembarkation was a study in practiced efficiency. There were no angry crowds, no jeering mobs spitting at the defeated enemy. There were only stevedores, military police, and the quiet, purposeful machinery of military processing.

This absence of public hatred was, in its own way, more disorienting than the cruelty they had anticipated. It suggested an indifference that was almost more insulting; their great, world-historical struggle had not even merited a public spectacle of scorn. They were marched from the gangplank to a waiting train, its carriages clean and its seats upholstered.

As the whistle blew, they began their final journey inland. Through the large, clean windows, they watched the American landscape scroll by like a motion picture. They saw small towns with neat wooden houses, each with its own lawn and a white picket fence. They saw cars parked in driveways, housewives hanging laundry on lines, and children playing on manicured grass.

It was a vision of profound, shocking normalcy. This was the country they had been at war with for nearly six years. A country that seemed so peaceful, so prosperous, so utterly unaware of the apocalyptic struggle they had just survived, that it felt like another planet. Their destination was Camp Pickett, a vast military base near Blackstone, Virginia.

And within its sprawling perimeter, a dedicated section had been fenced off and prepared: Prisoner of War Camp 180. As they were marched through the gates, they saw the barracks. Not the canvas tents of Reims, but sturdy wooden structures, painted a uniform olive drab and arranged in neat, orderly rows.

With its tidy streets and administrative buildings, it looked less like a prison and more like a strange, militarized summer camp. The camp commandant, a U.S. Army Colonel named Robert W. C. Wimsatt, addressed them through a translator. He was a career officer, stern-faced and professional. He laid out the rules of the camp, which were strict but clear.

They were prisoners of war, he stated, and they would be treated in accordance with the articles of the Geneva Conventions. They would be confined. They would be expected to work. But they would be treated with dignity. He was not there to punish them, he explained, but to administer their captivity according to the law. His tone was not one of vengeance, but of duty. It was the voice of the machine, now giving them their operating instructions.

What followed was a meticulous, almost bewildering process of organized care. They were issued new clothing: simple denim work dresses, fresh undergarments, and sturdy shoes. It was a uniform, a mark of their status, but it was clean, new, and whole—a stark contrast to the ragged, patched clothes of their final months in Germany.

They were assigned to barracks, each furnished with rows of metal cots, thick mattresses filled with fresh straw, and two woolen blankets per person. And then, they were led to the mess hall for their first meal on American soil. It was a cavernous, noisy space, but it was clean. They filed past a serving line, cafeteria-style, as American cooks in white aprons slopped food onto their trays.

Meatloaf with a thick brown gravy, a generous scoop of mashed potatoes, green beans, a slice of white bread with a pat of butter, and a glass of fresh, cold milk. To the German women, many of whom were suffering from the cumulative effects of years of rationing and malnutrition, it was a banquet of unimaginable proportions. They ate in a stunned, absolute silence. The sheer abundance was incomprehensible.

This was not the starvation diet of a vengeful victor. This was the food of a nation that had so much, it could afford to feed its enemies well, as a matter of routine. For some of the older, more fanatically indoctrinated women, the act of eating this meal was a source of deep, burning shame. They thought of their families back home, scavenging for potato peelings in the rubble of Berlin and Cologne.

How could they be here, eating this rich food, while their loved ones starved? It felt like a betrayal. For others, particularly the youngest, it was simply a relief so profound it bordered on the spiritual. They looked for the catch, the hidden motive. Was this some form of sophisticated psychological torture? Were they being fattened up for a worse fate? The enemy was supposed to be a monster.

But the monster kept giving them soap, hot water, and slices of pie. This persistent, organized humanity was a riddle they could not solve, and it slowly, inexorably began to change them from the inside out. The months at Camp Pickett settled into a strange and disorienting rhythm, a new normalcy defined by the paradox of confinement and comfort.

The initial shock and suspicion began to fade, replaced by a complex emotional landscape of guilt, gratitude, and a slowly dawning, deeply uncomfortable awareness. A routine was established, governed by bugle calls and the rigid timetable of military life. Wake-up call at dawn. Roll call, where they stood in silent rows as their numbers were read. Breakfast in the noisy mess hall.

Then, work assignments. The Geneva Conventions allowed for non-commissioned prisoners to be put to work, and the American camp administration took full advantage. The women were assigned to tasks that kept the camp functioning: shifts in the massive laundry, where they washed the uniforms of their captors; long hours in the hot kitchens, peeling potatoes and cleaning industrial-sized pots; or detailed work in the camp infirmary, folding bandages and sterilizing equipment under the supervision of American nurses. The work was tedious, but it was not brutal. It

was a means of passing the long, empty hours, and for it, they were compensated with a small amount of camp scrip, which they could use to purchase small luxuries like extra cigarettes, candy, or Coca-Cola at the camp PX—a concept so foreign and decadent it felt like a dream. The American guards, for the most part, kept their distance.

They were not fraternizing, but observing, their presence a constant, low-level reminder of their status. The true battle was not with their captors, but with their own minds, in the quiet hours after the evening meal and before the ten o’clock lights-out.

The barracks became their new world, a microcosm of defeated Germany, filled with whispered conversations, simmering resentments, and burgeoning doubts. The older, more fanatically indoctrinated women tried to maintain ideological discipline, warning the others not to be fooled by the enemy’s benevolence. “It is a trick,” they would hiss in the dark. “The Ami is clever.

He wants to break your spirit with kindness, to make you forget you are German. To make you soft.” But for the younger women, the daily, undeniable reality of hot meals, clean clothes, and personal safety began to erode the very foundations of their ideology. The enemy’s persistent, organized humanity was a riddle that was becoming impossible to ignore. The true re-education came not from formal, top-down programs, but from the cumulative effect of a thousand small, informal encounters and the subtle but powerful weapons of mercy deployed by the camp administration. One of the most effective of these was the camp library. It was a small,

simple room, but its shelves were stocked with German-language books—books that had been systematically banned and burned by their own government for over a decade. They found the works of Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Stefan Zweig, and other authors who had been declared enemies of the Reich. To read these books was a revolutionary act.

The stories they read, the historical accounts they absorbed, painted a picture of the war, of their own country, and of the world that violently contradicted the certainties of their youth. An even more powerful agent of change was the camp’s movie night. Once or twice a week, they would be marched to a recreation hall where a 16mm projector would be set up.

They watched American films with a mixture of fascination and contempt. They saw comedies, musicals, and dramas. They watched Bing Crosby croon his way through “White Christmas” and saw Judy Garland walk a Technicolor yellow brick road in a land called Oz. At first, they viewed these films as more obvious propaganda, a grotesque display of decadent American culture.

But the images were seductive. They depicted a world of vibrant color, of breathtaking material abundance, of personal freedom and a relentless, almost childlike optimism that stood in stark, painful contrast to the gray, rigid, sacrificial world they had left behind. They were seeing the evidence of a society that valued happiness, a concept that had been all but erased from their own political vocabulary, replaced by duty, honor, and death.

The Americans also showed them their own war propaganda—documentaries produced by the likes of Frank Capra and John Ford. And it was here that the most difficult reckoning began. For the first time in their lives, they saw the war not from the heroic perspective of the Wochenschau newsreels, which depicted German armies as noble liberators and righteous crusaders against Bolshevism, but from the Allied point of view.

They saw their own Luftwaffe bombing London, their own U-boats sinking civilian ships, their own armies marching into Paris not as heroes, but as conquerors. For many, this was deeply disturbing, but it was still within the realm of acceptable wartime narratives. The true collapse, the moment the world broke open, came when the camp authorities decided to show them the footage from the recently liberated concentration camps.

The war for their souls had begun, waged not with guns, but with food, books, and the relentless, undeniable evidence of their enemies’ compassion. The evening the films were shown was quiet. The women were marched into the recreation hall as usual, the mood a familiar mix of boredom and anticipation. But tonight, there was a different tension in the air.

The camp commandant, Colonel Wimsatt, was present, along with several of his officers, their faces grim. The lights went down, the projector whirred to life, and the screen flickered not with the familiar glamour of Hollywood, but with a grainy, stark black-and-white reality that would sear itself into their minds forever. The film began with a title card: German Concentration Camps Factual Survey.

What followed was a silent, unblinking record of hell on Earth, footage captured by British and American army cameramen at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, and Dachau. The first images were of the Allied soldiers, their faces etched with a horror that transcended nationality. Then came the images of what they had found.

Piles of human bodies, stacked like cordwood, their limbs tangled in a grotesque geometry of death. Bulldozers pushing mountains of emaciated corpses into mass graves. And then, the survivors. The walking skeletons, clad in striped pajamas, their eyes hollowed out into vast, dark pools of suffering. Men, women, and children stared into the camera with an ancient weariness, their bodies little more than frameworks of bone stretched over with translucent skin. The camera did not flinch.

It panned slowly across the crematoria, the ovens still filled with ash and bone fragments. It documented the piles of human hair, the warehouses filled with thousands of pairs of shoes, eyeglasses, and children’s toys. A profound and terrible silence fell over the hall, a silence so deep it felt like a physical pressure. The only sound was the steady, mechanical clicking of the projector.

The first sob was a choked, strangled gasp, and then it was a flood. Women began to weep uncontrollably, their bodies shaking with a grief so profound it seemed to come from the very center of the earth. Some fainted, slumping from their benches onto the floor. Others vomited, unable to contain the physical revulsion.

And the staunchest, most fanatical Nazis among them, the ones who had whispered of tricks and American cleverness, began to scream. “Lies! Propaganda! It is a trick!” they shouted, their voices shrill with a panicked denial. But their protests were drowned out by the overwhelming, irrefutable evidence on the screen.

The images were too raw, too real, too monstrous to be fabricated. This was not a trick. This was the truth. This was what they had been serving. The lights came up on a scene of utter devastation. The women were no longer prisoners of war; they were mourners at a funeral for their own souls. They had been betrayed.

Not by the Americans who showed them the film, but by their own leaders, their own culture, their own people, who had committed this unspeakable evil in their name. The foundation of their entire worldview—the belief in the moral righteousness of their cause, in the superiority of their nation, in the honor of their leaders—crumbled to dust in the space of twenty minutes. They had not been fighting for a noble cause.

They had been cogs in a machine of unimaginable evil. The shame was a physical force, a sickness that settled deep in their bones. In the aftermath of the screening, the social fabric of the prisoners tore apart. The hardliners became pariahs, their fanatical denials now ringing hollow even to themselves. The majority retreated into a quiet, personal space of contemplation and grief.

The kindness they had been shown in the camp was no longer a confusing riddle; it was a searing indictment. They had been taught to see their enemies as subhuman, while all along, the true barbarism was on their own side. The soap, the food, the clean clothes—these were not just acts of mercy.

They were the first steps in a long, painful journey of seeing themselves, and their nation, for what they truly were. Finally, in 1946, the long process of repatriation began. The women, now irrevocably changed, were processed for return. The journey back across the Atlantic was the reverse image of their initial passage.

They were traveling from a land of startling abundance and terrible knowledge back to the smoking, starved, unrecognizable ruins of Germany. The shock of re-entry was immense, but they carried with them a hidden, invaluable knowledge: the knowledge that their enemies were capable of mercy, and that their own side had been capable of the opposite. The greatest punishment these women ever received was not from a guard or an interrogator, but from the quiet, inescapable recognition that their enemies were good men, and that they had been fighting for the wrong side. The quiet lesson learned in a dusty American camp—that

decency survives even the deepest hatred, and that the truth, however horrifying, is the only path to redemption—was the one thing they carried with them into the rubble of their new lives, a truth as clear and resonant as the smell of fresh laundry and the lather of a bar of soap.

News

CH2 How One Woman’s “Crazy” Coffin Method Saved 2,500 Children From Treblinka in Just 1,000 Days

How One Woman’s “Crazy” Coffin Method Saved 2,500 Children From Treblinka in Just 1,000 Days November 16th, 1940. Ulica…

CH2 How One Jewish Fighter’s “Mad” Homemade Device Stopped 90 German Soldiers in Just 30 Seconds

How One Jewish Fighter’s “Mad” Homemade Device Stopped 90 German Soldiers in Just 30 Seconds September 1942. Outside Vilna,…

CH2 How One Brother and Sister’s “Crazy” Leaflet Drop Exposed 2,000 Nazis in Just 5 Minutes

How One Brother and Sister’s “Crazy” Leaflet Drop Exposed 2,000 Nazis in Just 5 Minutes February 22nd, 1943. Stadelheim…

CH2 The Forgotten Battalion of Black Women Who Conquered WWII’s 2-Year Mail Backlog

The Forgotten Battalion of Black Women Who Conquered WWII’s 2-Year Mail Backlog February 12th, 1945. A frozen ditch near…

CH2 How a Ranch-Hand Turned US Sniper Single-Handedly Crippled Three German MG34 Nests in Under an Hour—Saving 40 Men With Not a Single Casualty

How a Ranch-Hand Turned US Sniper Single-Handedly Crippled Three German MG34 Nests in Under an Hour—Saving 40 Men With Not…

CH2 The Untold Story of Freddy Oversteegen, the 14-Year-Old Who Lured N@zis to Their Deaths on Her Bicycle in Occupied Netherlands – The Untold WW2 Story

The Untold Story of Freddy Oversteegen, the 14-Year-Old Who Lured N@zis to Their Deaths on Her Bicycle in Occupied Netherlands…

End of content

No more pages to load