December 19, 1944 – German Generals Estimated 2 Weeks – Patton Turned 250,000 Men In 48 Hours

December 19, 1944.

Verdun, France.

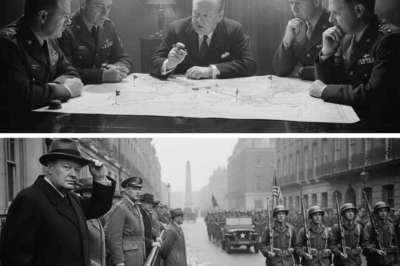

Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Command.

The air was heavy with cigarette smoke and the stale scent of wet wool. Outside, a freezing rain swept through the ruins of the old fortress city, while to the north, deep in the snow-covered Ardennes, German tanks were grinding westward, tearing a hole through the Allied line so wide that even the most optimistic staff officers could no longer pretend it was just a “local counterattack.”

Inside Eisenhower’s headquarters, maps were spread across long tables, their surfaces lit by the yellow glow of desk lamps. Thin, exhausted men in wrinkled uniforms bent over those maps, whispering coordinates and casualty estimates, their pencils trembling. Phones rang without pause. Radios crackled with broken transmissions. And beneath it all, there was that low, constant hum — the sound of a vast machine beginning to lose control of its own gears.

The Battle of the Bulge had begun three days earlier, and already it was threatening to tear the Western Front apart.

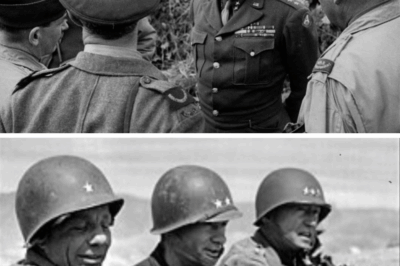

At 11:30 that morning, the door opened, and Lieutenant General George S. Patton walked in.

The room shifted.

Not loudly. Not noticeably. But unmistakably.

Conversations faltered. Heads turned. The clatter of typewriter keys slowed, then stopped. Even in war, Patton’s presence was a kind of weather — disruptive, magnetic, unpredictable. His polished helmet reflected the lamplight as he strode toward the map table, spurs clicking faintly against the wooden floor. He looked every bit the caricature his legend had already become — the ivory-handled pistols, the crisp uniform, the hard blue eyes that seemed to burn through anything they focused on.

Eisenhower looked up from the map and gestured him forward.

“George, we’re in a hell of a mess.”

Patton’s reply was characteristically dry. “I’ve been hearing that all morning.”

Around them, the atmosphere was near panic. The German counteroffensive — 250,000 men and over a thousand tanks — had smashed through the American lines in the Ardennes Forest. Towns were falling faster than reports could reach headquarters. Communications were breaking down. Entire divisions had vanished into the snow. Allied intelligence had missed the build-up completely.

Now the enemy was driving west, toward the Meuse River, threatening to split the Allied armies in two.

No one yet knew that this would become the largest battle ever fought by the United States Army. At that moment, it just felt like disaster.

Eisenhower leaned over the map, pointing toward the bulge that now jutted westward like a dagger aimed at the heart of Belgium. “Bradley’s First Army is shattered. Middleton’s VIII Corps is fighting with whatever’s left. Monty’s slow to react. We need to counterattack — but from where?”

He looked at Patton.

“How long would it take you to turn your Third Army north?”

The room stilled.

It was the question everyone had feared — and the one only Patton seemed to have expected.

Patton didn’t blink. “Forty-eight hours,” he said.

Someone actually laughed. A short, disbelieving bark.

Another officer muttered, “He’s lost his damn mind.”

Eisenhower frowned. “You’re telling me you can turn an entire field army — six divisions, tens of thousands of vehicles — ninety degrees, disengage from active combat, move a hundred miles, and attack in two days?”

Patton’s jaw tightened. “Yes, sir. I can.”

It sounded impossible. It was impossible — by every known rule of logistics. But George S. Patton didn’t live by rules. He made them, bent them, or broke them, as required by the moment.

The silence stretched.

Then Eisenhower asked, cautiously, “You’re sure you can do that?”

Patton grinned — that sharp, dangerous grin that always seemed halfway between amusement and challenge.

“I’ve already got the plans, Ike.”

That was the part nobody in the room knew — not Eisenhower, not Bradley, not the British liaison officers watching from the corner. While the rest of the Allied command had been relaxing after the capture of Metz, Patton had been drafting contingency plans for exactly this kind of German counterattack. Three separate operations — each detailing a ninety-degree pivot north, complete with road assignments, unit movements, supply routes, and communication codes.

To everyone else, the Ardennes had seemed safe — a quiet sector manned by inexperienced troops. To Patton, it had looked like an invitation.

He’d seen what others didn’t: the thin American line, the overconfidence, the gaps in reconnaissance, the perfect terrain for surprise.

He had been planning for disaster before it even had a name.

Now, that foresight was about to make history.

Eisenhower stared at him for a long moment, then finally nodded. “Do it.”

Patton turned to his chief of staff, General Hobart Gay.

“Send the orders,” he said. “We’re moving north.”

And just like that — before anyone had even left the room — the impossible began.

Patton’s Third Army was no small instrument. It was a steel leviathan — six combat divisions, more than 250,000 men, over 1,500 tanks, and a logistical tail that stretched hundreds of miles back into France. To move it was to move a city. And to turn it ninety degrees, across frozen roads and snow-choked hills, under constant threat of German air attacks and counterstrikes, was an operation so complex that even the German high command believed it couldn’t be done in less than two weeks.

Patton would do it in two days.

In Nancy, headquarters of the Third Army, the first orders were transmitted within hours of the meeting. Communications officers hunched over radios, relaying coded messages to divisions scattered across eastern France: stand down, disengage, prepare to move north immediately.

Convoys began forming before midnight. Supply trains that had been rolling east were diverted north. Engineers were dispatched to scout new routes. Fuel and ammunition dumps were re-established overnight. There were no protests, no delays. Patton’s staff had learned long ago that hesitation was death in his army.

Meanwhile, to the north, in the snow-covered Ardennes, the Germans were celebrating.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was convinced he had achieved strategic surprise. His intelligence officers reported that Patton’s Third Army was bogged down near Saarbrücken, over a hundred miles away, still fighting remnants of the German 1st Army. By all logic, it couldn’t possibly intervene in time.

“Two weeks,” one German general estimated. “We have at least two weeks before Patton can threaten our flank.”

They were wrong by twelve days.

To understand why, you had to understand the difference between German and American logistics. The Wehrmacht operated like a craftsman — precise, meticulous, but dependent on perfection. Patton’s army operated like an industrial engine: fast, adaptable, and redundant. If a truck broke down, another replaced it. If fuel ran short, supply officers commandeered civilian vehicles or rerouted convoys without waiting for permission.

Patton had built a culture that thrived on motion.

He called it “the Red Ball spirit” — the relentless mindset that had carried the Allies across France after Normandy. And now, he was about to push that spirit into overdrive.

Within twelve hours, entire armored divisions were pulling away from their defensive positions near Metz, engines rumbling through the night. Snow whipped across their windshields as columns of Shermans, half-tracks, and jeeps stretched across the roads — headlights dimmed, engines roaring, a steel serpent moving north through the storm.

Mechanics worked without sleep, fixing broken gear in the freezing cold. Quartermasters established temporary fuel points along the roads. Bridges were reinforced to handle the tonnage of tanks. In towns along the route, locals watched in awe as the American war machine thundered past, endless convoys heading into the storm.

Soldiers wrapped scarves around their faces, hunched under heavy packs, boots crunching through ice. Nobody complained. Everyone knew what was at stake. The 101st Airborne was surrounded at Bastogne. The Germans were pushing west toward the Meuse. If they broke through, they could split the Allied armies and perhaps even reach Antwerp. The war could drag on for years.

Patton wasn’t just moving to save a division. He was moving to save the Western Front.

At Eisenhower’s headquarters, skepticism remained. Some of the staff thought Patton was bluffing — that he was trying to preserve his reputation with impossible promises. But Eisenhower, who had come to understand the strange genius of the man, had placed his bet.

“He’ll do it,” Ike told Bradley quietly. “If anyone can, it’s Patton.”

And by the following morning, as the first reports began filtering in — armored columns already halfway north, roads cleared, logistics intact — even the doubters began to believe.

Across the Ardennes, the Germans still thought they had time. They were wrong.

Because Patton’s army — that unstoppable, furious, untamed creation of American willpower and discipline — was already in motion.

And in less than forty-eight hours, it would arrive like a thunderclap from the south, shattering every assumption the Reich’s generals had made.

What the Germans thought was impossible was, to George Patton, merely difficult.

And he had never been afraid of difficult.

Continue below

December 19, 1944.

Verdun, France.

Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Command.

The air was heavy with cigarette smoke and the stale scent of wet wool. Outside, a freezing rain swept through the ruins of the old fortress city, while to the north, deep in the snow-covered Ardennes, German tanks were grinding westward, tearing a hole through the Allied line so wide that even the most optimistic staff officers could no longer pretend it was just a “local counterattack.”

Inside Eisenhower’s headquarters, maps were spread across long tables, their surfaces lit by the yellow glow of desk lamps. Thin, exhausted men in wrinkled uniforms bent over those maps, whispering coordinates and casualty estimates, their pencils trembling. Phones rang without pause. Radios crackled with broken transmissions. And beneath it all, there was that low, constant hum — the sound of a vast machine beginning to lose control of its own gears.

The Battle of the Bulge had begun three days earlier, and already it was threatening to tear the Western Front apart.

At 11:30 that morning, the door opened, and Lieutenant General George S. Patton walked in.

The room shifted.

Not loudly. Not noticeably. But unmistakably.

Conversations faltered. Heads turned. The clatter of typewriter keys slowed, then stopped. Even in war, Patton’s presence was a kind of weather — disruptive, magnetic, unpredictable. His polished helmet reflected the lamplight as he strode toward the map table, spurs clicking faintly against the wooden floor. He looked every bit the caricature his legend had already become — the ivory-handled pistols, the crisp uniform, the hard blue eyes that seemed to burn through anything they focused on.

Eisenhower looked up from the map and gestured him forward.

“George, we’re in a hell of a mess.”

Patton’s reply was characteristically dry. “I’ve been hearing that all morning.”

Around them, the atmosphere was near panic. The German counteroffensive — 250,000 men and over a thousand tanks — had smashed through the American lines in the Ardennes Forest. Towns were falling faster than reports could reach headquarters. Communications were breaking down. Entire divisions had vanished into the snow. Allied intelligence had missed the build-up completely.

Now the enemy was driving west, toward the Meuse River, threatening to split the Allied armies in two.

No one yet knew that this would become the largest battle ever fought by the United States Army. At that moment, it just felt like disaster.

Eisenhower leaned over the map, pointing toward the bulge that now jutted westward like a dagger aimed at the heart of Belgium. “Bradley’s First Army is shattered. Middleton’s VIII Corps is fighting with whatever’s left. Monty’s slow to react. We need to counterattack — but from where?”

He looked at Patton.

“How long would it take you to turn your Third Army north?”

The room stilled.

It was the question everyone had feared — and the one only Patton seemed to have expected.

Patton didn’t blink. “Forty-eight hours,” he said.

Someone actually laughed. A short, disbelieving bark.

Another officer muttered, “He’s lost his damn mind.”

Eisenhower frowned. “You’re telling me you can turn an entire field army — six divisions, tens of thousands of vehicles — ninety degrees, disengage from active combat, move a hundred miles, and attack in two days?”

Patton’s jaw tightened. “Yes, sir. I can.”

It sounded impossible. It was impossible — by every known rule of logistics. But George S. Patton didn’t live by rules. He made them, bent them, or broke them, as required by the moment.

The silence stretched.

Then Eisenhower asked, cautiously, “You’re sure you can do that?”

Patton grinned — that sharp, dangerous grin that always seemed halfway between amusement and challenge.

“I’ve already got the plans, Ike.”

That was the part nobody in the room knew — not Eisenhower, not Bradley, not the British liaison officers watching from the corner. While the rest of the Allied command had been relaxing after the capture of Metz, Patton had been drafting contingency plans for exactly this kind of German counterattack. Three separate operations — each detailing a ninety-degree pivot north, complete with road assignments, unit movements, supply routes, and communication codes.

To everyone else, the Ardennes had seemed safe — a quiet sector manned by inexperienced troops. To Patton, it had looked like an invitation.

He’d seen what others didn’t: the thin American line, the overconfidence, the gaps in reconnaissance, the perfect terrain for surprise.

He had been planning for disaster before it even had a name.

Now, that foresight was about to make history.

Eisenhower stared at him for a long moment, then finally nodded. “Do it.”

Patton turned to his chief of staff, General Hobart Gay.

“Send the orders,” he said. “We’re moving north.”

And just like that — before anyone had even left the room — the impossible began.

Patton’s Third Army was no small instrument. It was a steel leviathan — six combat divisions, more than 250,000 men, over 1,500 tanks, and a logistical tail that stretched hundreds of miles back into France. To move it was to move a city. And to turn it ninety degrees, across frozen roads and snow-choked hills, under constant threat of German air attacks and counterstrikes, was an operation so complex that even the German high command believed it couldn’t be done in less than two weeks.

Patton would do it in two days.

In Nancy, headquarters of the Third Army, the first orders were transmitted within hours of the meeting. Communications officers hunched over radios, relaying coded messages to divisions scattered across eastern France: stand down, disengage, prepare to move north immediately.

Convoys began forming before midnight. Supply trains that had been rolling east were diverted north. Engineers were dispatched to scout new routes. Fuel and ammunition dumps were re-established overnight. There were no protests, no delays. Patton’s staff had learned long ago that hesitation was death in his army.

Meanwhile, to the north, in the snow-covered Ardennes, the Germans were celebrating.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was convinced he had achieved strategic surprise. His intelligence officers reported that Patton’s Third Army was bogged down near Saarbrücken, over a hundred miles away, still fighting remnants of the German 1st Army. By all logic, it couldn’t possibly intervene in time.

“Two weeks,” one German general estimated. “We have at least two weeks before Patton can threaten our flank.”

They were wrong by twelve days.

To understand why, you had to understand the difference between German and American logistics. The Wehrmacht operated like a craftsman — precise, meticulous, but dependent on perfection. Patton’s army operated like an industrial engine: fast, adaptable, and redundant. If a truck broke down, another replaced it. If fuel ran short, supply officers commandeered civilian vehicles or rerouted convoys without waiting for permission.

Patton had built a culture that thrived on motion.

He called it “the Red Ball spirit” — the relentless mindset that had carried the Allies across France after Normandy. And now, he was about to push that spirit into overdrive.

Within twelve hours, entire armored divisions were pulling away from their defensive positions near Metz, engines rumbling through the night. Snow whipped across their windshields as columns of Shermans, half-tracks, and jeeps stretched across the roads — headlights dimmed, engines roaring, a steel serpent moving north through the storm.

Mechanics worked without sleep, fixing broken gear in the freezing cold. Quartermasters established temporary fuel points along the roads. Bridges were reinforced to handle the tonnage of tanks. In towns along the route, locals watched in awe as the American war machine thundered past, endless convoys heading into the storm.

Soldiers wrapped scarves around their faces, hunched under heavy packs, boots crunching through ice. Nobody complained. Everyone knew what was at stake. The 101st Airborne was surrounded at Bastogne. The Germans were pushing west toward the Meuse. If they broke through, they could split the Allied armies and perhaps even reach Antwerp. The war could drag on for years.

Patton wasn’t just moving to save a division. He was moving to save the Western Front.

At Eisenhower’s headquarters, skepticism remained. Some of the staff thought Patton was bluffing — that he was trying to preserve his reputation with impossible promises. But Eisenhower, who had come to understand the strange genius of the man, had placed his bet.

“He’ll do it,” Ike told Bradley quietly. “If anyone can, it’s Patton.”

And by the following morning, as the first reports began filtering in — armored columns already halfway north, roads cleared, logistics intact — even the doubters began to believe.

Across the Ardennes, the Germans still thought they had time. They were wrong.

Because Patton’s army — that unstoppable, furious, untamed creation of American willpower and discipline — was already in motion.

And in less than forty-eight hours, it would arrive like a thunderclap from the south, shattering every assumption the Reich’s generals had made.

What the Germans thought was impossible was, to George Patton, merely difficult.

And he had never been afraid of difficult.

The order had gone out on the night of December 19, 1944, and by midnight the roads of eastern France had begun to hum.

Engines coughed to life. Men packed rations and ammunition, stowed what they could not carry, and turned their columns north. It was the dead of winter, the coldest in Europe in years. Snow drifted knee-deep along the verges. Headlights were covered with slitted tape, throwing weak yellow slashes through the darkness. From Nancy to Luxembourg, the movement was underway.

The Third Army was a living organism—armored spearheads, infantry divisions, engineer battalions, supply trains, field hospitals. Each piece depended on every other, and none of it could stop. To turn that organism ninety degrees and send it charging into the frozen hills of the Ardennes within forty-eight hours would have broken most armies. But Patton’s men had long ago learned that when the old man said move, you moved.

He rode at the front of his command convoy, gloved hands tight on the wheel of his jeep, eyes fixed north through the blowing snow. Beside him, his driver, Sergeant Francis “Babe” Knauss, kept the vehicle steady on roads that had turned to glass. Every few miles they passed another stalled truck being pulled to the side, another Sherman tank with a crew working under the hood, breath rising in clouds. Patton would slow, shout a few words, sometimes jump out and bark orders himself, then climb back in and roll on. “Keep moving!” he yelled into the wind. “The faster we go, the sooner we kill those bastards.”

Behind him stretched an army that defied arithmetic: six divisions, a hundred thousand vehicles, fuel for only three days, yet somehow advancing as if the weather and terrain had been made for them.

At the corps headquarters, Major General Manton Eddy read the new orders twice to be sure he had not misunderstood. The 4th Armored Division was to disengage from combat near Saarlautern, wheel north ninety miles, and be ready to attack the Germans outside Bastogne in forty-eight hours. “It can’t be done,” one colonel muttered. Eddy looked up from the paper. “Then we’ll do it anyway.”

Through the night they did. Convoys snaked through mountain passes, engines roaring and backfiring in the cold. Bridges iced over. Fuel trucks slid into ditches. Engineers rigged winches to pull them free. In the pitch darkness, headlights hidden from German aircraft, MPs guided traffic with flashlights wrapped in red cloth. One by one, entire regiments disappeared into the white silence and reappeared on the roads north.

It was not elegant, but it was movement, and movement was life.

At Metz, Colonel Oscar Koch, Patton’s intelligence officer, studied reports coming from forward scouts. The German advance was spreading faster than anyone had predicted. Town after town—St. Vith, Clervaux, Houffalize—had fallen. Koch understood what that meant: if the Germans reached the Meuse before the Third Army arrived, they could cut the Allied front in half. He went to Patton’s field tent, map in hand. “If we’re late by even a day—” he began.

Patton didn’t look up. “Then we won’t be late.”

He was thinking of Bastogne. The 101st Airborne Division was trapped there now, surrounded by armored columns from the 2nd Panzer and Panzer Lehr Divisions. Supplies were running out; the skies were closed by snow and fog. Radio intercepts spoke of German officers calling on the Americans to surrender. Patton knew what was at stake. If Bastogne fell, the enemy would control every road junction in the Ardennes. He intended to reach it first.

By dawn on the 21st, the first elements of the Third Army were entering Luxembourg. The landscape changed from the broad plains of Lorraine to dense forest and winding roads hemmed in by snowbanks. The temperature had dropped to eight degrees Fahrenheit. Weapons froze; rifle bolts had to be warmed over engine exhausts. The oil in tank engines turned to jelly. Soldiers wrapped burlap around their boots and stuffed newspapers under their jackets. Yet still they moved.

Sergeant Joe Pyle of the 26th Infantry later wrote, “We didn’t sleep. We didn’t talk. We just marched and rode. Every time a truck stopped, another started. It was like the whole world was headed north.”

The German commanders, meanwhile, were congratulating themselves. In the villa that served as their forward headquarters, Field Marshal von Rundstedt studied his own maps. He knew Patton was to the south, but by his calculations it would take at least two weeks to disengage and reposition. “We have the initiative,” he told his staff. “The Americans will need time to react. By then it will be too late.” They raised glasses of schnapps to celebrate. Outside, the snow kept falling.

They had no idea that the sound in the distance—the low, steady rumble they heard at night—was the Third Army on the move.

The key to Patton’s miracle was not magic but organization. Every division had been pre-assigned road routes, timing intervals, fuel stops, and alternate paths in case of blockage. Quartermasters established temporary depots along the highways using whatever they could find—barns, schoolyards, church courtyards—filled with jerry cans and crates of ammunition. Broken vehicles were stripped for parts on the spot. There was no time to repair; replacement was faster.

Patton’s orders were blunt: If it moves, drive it north. If it doesn’t, push it until it does.

By December 22, the lead elements of the 4th Armored Division had reached the outskirts of Arlon. The men were filthy, unshaven, half-frozen, but their morale was electric. They knew they were racing against time to relieve Bastogne, and every mile gained was another slap in the face to the Germans who thought them incapable of such speed.

That night, Patton called a meeting of his corps commanders in a small Luxembourg farmhouse. The fire in the hearth barely warmed the room. Maps covered the table. Outside, the wind howled against the shutters. Patton pointed his riding crop toward Bastogne. “Gentlemen, the 101st is holding by their fingernails. We’re going to break that ring in forty-eight hours. If any of you think that can’t be done, I don’t want to hear it. I only want to hear how it will be done.”

No one argued. They knew better.

Then he turned to his chaplain, Colonel James O’Neill. “Chaplain,” he said, “I want you to write me a prayer for good weather.”

O’Neill hesitated, unsure he had heard correctly. “A prayer for weather, sir?”

“Good weather,” Patton repeated. “For killing Germans.”

The next morning, thousands of copies of that prayer were distributed to the troops:

Almighty and most merciful Father, grant us fair weather for battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies.

Men read it aloud in foxholes and trucks. Some laughed. Some tucked it into their helmets. But the words traveled with them as they drove north through the storm.

The weather, for the moment, was merciless.

By December 23, six more inches of snow had fallen. Visibility was near zero. Convoys crawled at five miles per hour. Radio lines failed; batteries froze solid. Yet the army kept its timetable. The forward command post shifted to Luxembourg City, from which Patton directed the assault like a conductor leading an orchestra only he could hear. He barely slept. His staff saw him pacing outside his tent long before dawn, coat flapping in the wind, muttering calculations. “If the 4th Armored reaches Martelange by nightfall, Bastogne by the 25th,” he said to no one in particular, “then we’ve beaten every prediction the Germans ever made.”

That afternoon, the clouds began to thin. Shafts of sunlight pierced the gray, glinting off the endless line of tanks on the road. Then, around 1600 hours, the sky opened. The snow stopped. Blue spread across the horizon like a promise. Allied pilots, grounded for a week, scrambled to their planes. Within hours, Thunderbolts and Typhoons were sweeping over the battlefield, strafing German columns caught in the open. The men on the ground cheered. “The weather broke!” someone shouted. “The chaplain did it!”

For the Germans, the change was catastrophic. Their supply lines, already stretched, now lay exposed to relentless air attacks. Fuel convoys went up in flames. Columns of Panzers, unable to move on the icy roads, became stationary targets. The same snow that had hidden them now trapped them.

That night, as Patton studied reports by lantern light, his operations officer handed him a message from the 101st Airborne. The Germans had sent a surrender demand to Bastogne. Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe’s reply had been one word: “Nuts.”

Patton laughed so hard the lantern shook. “A man after my own heart,” he said. “Now let’s go get those boys.”

The next day, Christmas Eve, the 4th Armored Division reached the village of Chaumont, twenty miles from Bastogne. The road ahead was mined and defended by German armor, but the column pressed forward through the night, the roar of engines echoing through the frozen forest. At dawn on the 26th, Lieutenant Charles Boggess of the 37th Tank Battalion spotted the church spire of Bastogne in the distance. He keyed his radio: “We’re coming through!”

Minutes later, his lead tank broke the last German roadblock and rolled into the town. Soldiers of the 101st, gaunt and weary, emerged from cellars and foxholes to meet them. Boggess climbed out of his Sherman and shouted, “Come here, this is the Fourth Armored!”

The siege was broken. The men of Bastogne were saved.

Behind that victory lay the true miracle: 250,000 men, six divisions, turned and thrown into battle in less than two days. No modern army had ever moved so far, so fast, under such conditions. Patton had promised forty-eight hours. He had delivered.

In the German headquarters, disbelief replaced triumph. Rundstedt demanded explanations. How had the Americans moved so quickly? How had they attacked from a direction no one had thought possible? His operations chief could only stammer: “It should have taken two weeks, sir. We have no idea how they did it.”

They never would understand.

Patton’s secret was simple: he had refused to wait for orders, refused to fear failure, and refused to let reason stand in the way of necessity. To him, war was not a matter of perfect plans. It was motion, will, and speed—and those were things the Third Army possessed in abundance.

By the time the last tank of his column rolled into Bastogne, the myth was complete.

The man the Germans feared most had done what even his allies thought impossible.

December 26, 1944.

The Ardennes, Belgium.

Snow fell again, light and silent, over a battlefield littered with the wreckage of tanks, trucks, and shattered trees. Smoke rose from smoldering villages. The air reeked of oil and cordite. But in the center of that frozen hell, inside the battered town of Bastogne, a miracle had taken place.

American tanks had arrived.

At 16:50 hours, Lieutenant Charles Boggess and the lead platoon of the 37th Tank Battalion had smashed through the last German barricade. The men of the 101st Airborne—filthy, frostbitten, eyes sunken from days without sleep—watched in disbelief as olive-drab Shermans rolled into the town square. They had held out for a week under constant artillery fire and freezing cold, surrounded on all sides, food and ammunition nearly gone. Now, at last, relief had come.

The soldiers of the 4th Armored Division were just as stunned. They’d driven for nearly forty-eight hours through blizzards and enemy fire, averaging barely five miles an hour, sleeping in their tanks, subsisting on cold rations. When the two groups met, there were no speeches, just laughter, shouts, and the kind of exhausted joy that only comes after surviving the impossible. A paratrooper slapped the side of a tank and yelled, “You took your damn time getting here!” The tanker grinned back. “We got lost in the snow.”

The siege of Bastogne was broken, but the Battle of the Bulge was far from over.

Thirty miles south, in a commandeered chateau serving as the Third Army’s forward headquarters, George S. Patton studied his maps under the yellow light of an oil lamp. His face was gaunt from lack of sleep, his uniform spattered with mud, his gloves stiff with frost. Outside, the wind moaned through the shutters like a wounded animal. Reports were coming in every few minutes—German withdrawals, supply shortages, counterattacks that fizzled and died in the snow.

He leaned back in his chair, exhaustion tugging at his eyelids. Across the room, his chief of staff, General Hobart Gay, poured two cups of coffee and handed one to him. “Congratulations, George,” Gay said quietly. “You did it in forty-eight hours. Bastogne’s free.”

Patton nodded but didn’t smile. “We’re not finished yet,” he said. “Not until we crush what’s left of that damn bulge.”

Gay studied him for a moment. “They said it couldn’t be done.”

Patton stared at the map, where red arrows showed the German advance still curving westward. “That’s because they think in straight lines,” he said. “I think in circles. Always have.”

Outside, the sounds of an army on the move filled the night—engines starting, trucks grinding gears, soldiers shouting orders through the snow. Patton stood, walked to the window, and watched the faint glow of headlights moving along the distant road. “Every one of those men is the reason we broke through,” he said softly. “They’re the ones who did the impossible.”

Over the next week, the German offensive collapsed under its own weight.

Fuel—the lifeblood of mechanized war—had run out. Hitler’s plan had depended on capturing Allied supply depots, but the depots had been destroyed or moved before his tanks arrived. The mighty armored spearheads, once racing west, now stood frozen in place, their engines silent, their crews shivering in the cold. Many abandoned their vehicles and tried to escape on foot.

Patton’s counterattack pressed relentlessly northward, squeezing the bulge from below as British forces moved down from the north. Towns that had been lost in the first days of the offensive—Ettelbruck, Houffalize, Neufchâteau—were retaken one by one. Each was a ruin of blackened stone and snow, each paid for in blood.

In one captured German command post, Patton’s officers found detailed maps showing the German expectations: Third Army – immobilized until early January. Von Rundstedt’s staff had written in pencil beside the note, Estimated delay: 14 days minimum.

Patton read it and smiled grimly. “They were only off by twelve,” he said.

The irony was brutal. The same industrial power the Germans had mocked as “clumsy” and “mechanized” had out-marched and out-fought the most disciplined army in Europe. American logistics, decentralized and adaptive, had turned the tide. Fuel and ammunition arrived wherever Patton’s men went. Wrecked tanks were replaced faster than they could burn out. And the skies, now clear, belonged entirely to the Allies. Fighter-bombers strafed retreating German convoys with impunity. The Luftwaffe was finished.

On December 28th, Patton radioed General Omar Bradley: “Brad, the Kraut stuck his head in a meat grinder, and I’ve got hold of the handle.”

Bradley’s reply crackled through the static. “Then turn it.”

And Patton did.

In the first days of January 1945, the Allied counteroffensive surged. The bulge began to flatten. German casualties mounted beyond recovery—over 100,000 men killed, wounded, or captured, along with hundreds of tanks and artillery pieces. What Hitler had called his Wacht am Rhein, his final gamble in the West, had become a catastrophe. His armored divisions were gutted, his reserves gone, his hopes of negotiating peace with the Western Allies shattered.

For the men of the Third Army, victory came at a terrible price. Thousands had frozen to death in their foxholes. Dozens of tanks lay half-buried in snow, engines burned out, their crews still inside. Yet morale remained fierce. They knew what they had accomplished. They had turned a rout into redemption, and they had done it under the command of a man who refused to acknowledge the word “impossible.”

On January 16th, American forces advancing from the north and south met at the town of Houffalize, closing the pocket. The Battle of the Bulge was over.

When Patton arrived at the front the next day, soldiers cheered as he drove past in his jeep, the famous ivory-handled revolvers glinting at his side. He stood up, saluted the men, and shouted, “You magnificent bastards, you did it!”

The cheers followed him down the road until they faded into the sound of engines and wind.

The victory cemented his legend.

Newsreels showed the Third Army grinding through snow and fire, headlines called it “Patton’s Miracle,” and even Eisenhower—no man easily impressed—called it “one of the finest performances in the history of the U.S. Army.” Churchill would later tell Parliament, “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will be regarded as an ever-famous American victory.”

In the ruins of the Reich, German generals were asked in interrogation what they thought of Patton.

General Günther Blumentritt, who had served under von Rundstedt, answered without hesitation:

“We regarded General Patton extremely highly—as the most modern commander on the battlefield. We did not expect him to react so quickly. We thought we would have at least two weeks before the Third Army could respond. He did it in two days. Extraordinary.”

Another, General Hasso von Manteuffel, put it more simply.

“When we learned Patton was moving north, we knew the attack was over.”

Patton, for his part, took little credit. In his diary on December 27th, he wrote, “The ability to get the Third Army turned and attacking in under three days will probably be considered a masterpiece of logistics and planning. But it is really quite simple when you know what you’re doing.”

He ended the entry with a single line that revealed everything about his philosophy:

“In war, the impossible is often just the difficult that nobody else dares to try.”

The men who had laughed in Verdun when he promised forty-eight hours had stopped laughing long ago.

When the snows of winter finally began to melt in March 1945, the roads that once echoed with retreat now carried the steady thunder of Allied armor rolling eastward toward Germany. Patton led the Third Army across the Rhine, smashing through what remained of Hitler’s defenses. Within months, the war in Europe would be over.

But for Patton, the end came too soon. In December 1945, almost exactly one year after Bastogne, he was killed in a car accident near Mannheim. He was sixty years old. Some said it was a cruel irony—that the man who had survived the bloodiest battles of the century should die on a quiet German road. Others said it was fitting, that Patton had never been built for peace.

He was buried among his soldiers in the Luxembourg American Cemetery, not far from the ground his army had saved. His grave lies in the front row, facing the thousands of white crosses of the men who followed him north that winter. The inscription is simple:

George S. Patton, Jr.

General, Third Army.

Every winter, when the snow falls over the Ardennes, the locals still tell the story of the army that came out of the blizzard like a ghost—250,000 men who turned north in forty-eight hours and changed the course of the war.

And they tell it the way Patton would have liked best—not as a tale of miracles, but of will. Of movement. Of men who refused to stop.

The Germans had thought they had two weeks.

Patton gave them two days.

And by the time they realized their mistake, it was already too late.

The bulge was gone.

The Reich was doomed.

And history had found its storm.

News

CH2 What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time

What Churchill Said When He Saw American Troops Marching Through London for the First Time December 7, 1941. It…

CH2 Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult

Why Patton Refused To Enter Bradley’s Field HQ – The Frontline Insult On the morning of August 3rd, 1943, the…

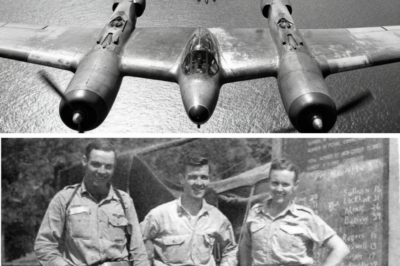

CH2 Japanese Air Force Underestimated The US – They Was Utterly Stunned by America’s Deadly P-38 Lightning Strikes

Japanese Air Force Underestimated The US – They Was Utterly Stunned by America’s Deadly P-38 Lightning Strikes The morning air…

CH2 They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs At 8:44 a.m. on June…

CH2 They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle

They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle July 23, 1943. 0600 hours. The Sicilian…

CH2 What Japanese High Command Said When They Finally Understood American Power Sent Chill Down Their Spines

What Japanese High Command Said When They Finally Understood American Power Sent Chill Down Their Spines August 6, 1945….

End of content

No more pages to load