3,000 Casualties vs 3 – The Deadliest Trap of WW2 Laid By One 19-Year-Old’s Codebreaking and a Midnight Naval Ambush

March 1941. The Mediterranean stretched out like a sheet of burnished glass, shimmering beneath a winter sun that seemed too gentle for a sea preparing for war. The water looked peaceful—placid, even—but beneath that calm silver surface, two vast navies were closing in on each other, their commanders unaware that within forty-eight hours, one of them would walk willingly into the deadliest ambush of the war.

Aboard the Italian flagship Vittorio Veneto, the pride of Mussolini’s navy, Admiral Angelo Iachino stood surrounded by officers, his white-gloved hands resting on the polished edge of the plotting table. The flagship was a masterpiece of naval engineering—nine 15-inch guns mounted in massive triple turrets, armor thick enough to shrug off anything but a direct hit, and engines capable of driving her through the sea at more than thirty knots. To the admiral and his men, Vittorio Veneto was more than a ship; she was a floating embodiment of national pride.

Iachino was in good spirits. His intelligence officers had confirmed that Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, was relaxing in Alexandria, far from the front lines. Reports claimed that Cunningham had spent the last several days entertaining foreign diplomats, attending luncheons, and even—according to one informant—playing golf. If that were true, then Britain’s Mediterranean fleet was effectively blind and immobile. The Italian admiral leaned over the chart table, a thin smile forming beneath his mustache. “Cunningham has no idea,” he said quietly. “We will strike before the British even leave their harbors.”

Around him, the atmosphere pulsed with restrained excitement. Officers in crisp uniforms bent over maps, plotting intercept courses, their voices low but confident. The Vittorio Veneto’s operations room smelled faintly of machine oil and salt air, the mingled odors of a ship built for both precision and destruction. Every man aboard could feel it: this would be the moment Italy reclaimed its honor.

For months, the Regia Marina had lived in the shadow of the Royal Navy. Their ships were fast, elegant, and modern, yet time and again they had been thwarted—ambushed by aircraft at Taranto, outmaneuvered by convoys that seemed to know their every move, outsmarted by an enemy that appeared to be everywhere at once. Italian morale was battered. But now, Iachino believed, that would change. The gods of war had finally handed him an opportunity.

At 0600 hours, a radio message crackled through from reconnaissance pilots: British ships had been sighted in the Aegean Sea, heading northwest. The report was clear—four light cruisers and several destroyers, a small force, lightly escorted. The admiral straightened, eyes alight. “Perfect,” he said. “They’re convoy escorts. We will crush them before dawn.”

The order rippled through the fleet. Signal flags unfurled, engines roared to life, and twenty-two Italian warships swung into formation. The Vittorio Veneto surged forward, her massive bow cutting a gleaming white furrow through the water. From above, she looked unstoppable—a moving fortress of steel and gunfire, her flanks shimmering beneath the Mediterranean sun. Sailors cheered from the decks, unaware that the moment they left port, their fate was already sealed.

Because while Iachino believed himself the hunter, in truth, he had already become the hunted.

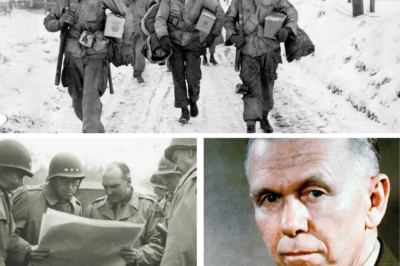

Hundreds of miles away, in the English countryside northwest of London, another kind of battle was being fought—a silent one, waged not with torpedoes or bombs but with pencils, typewriters, and sheer intellect. At Bletchley Park, the British codebreaking center, the air was thick with cigarette smoke and tension. In one corner of a cramped, paper-strewn room, a nineteen-year-old woman named Mavis Batey hunched over a desk piled high with sheets of intercepted Italian naval transmissions.

The messages were long columns of meaningless letters—strings of gibberish encrypted by the Italian version of the Enigma machine. Dozens of cryptanalysts had tried and failed to break them. But Mavis, soft-spoken and self-effacing, possessed a rare intuition. Her professors at University College London had once said she had the kind of mind that saw patterns where others saw chaos. That morning, acting on a hunch, she made a small, unauthorized adjustment to the settings of her decoding wheel. It was an instinctive move, half logic and half faith, and within moments, something extraordinary happened.

The jumble of random characters began to rearrange into words.

Her eyes widened as the letters resolved into a short, chilling message: “Today’s the day minus three.”

For a moment, she simply stared at it, her heart pounding. Then she scribbled it down, calling to a nearby officer. “I think I’ve got something.” Hours later, as more intercepts poured in, the truth emerged. The Italians were preparing a major naval operation—an ambush against British convoys bound for Greece. For the first time, the British command knew not just what the enemy was planning, but when and where they intended to strike.

That knowledge—gained through patience, brilliance, and a teenager’s intuition—would change the course of the war in the Mediterranean.

But intelligence alone would not win the battle. If the Italians suspected their codes were broken, they would change them instantly, cutting off Britain’s advantage. Cunningham could not act in a way that revealed foreknowledge. So the British devised an elaborate deception. A Short Sunderland flying boat, officially on a “routine patrol,” was ordered to pass near the area where the Italian fleet would be.

Its pilot, unaware of any secret plan, was genuinely thrilled when, through a break in the clouds seventy-five miles east of Sicily, he glimpsed a sight that made his heart race—steel hulls glinting in formation far below, twenty-two of them, cutting through the sea like a pack of sharks. He counted them quickly: the battleship Vittorio Veneto, cruisers Zara, Fiume, Pola, Trento, Trieste, Bolzano, Garibaldi, Abruzzi, and thirteen destroyers escorting them. The pilot’s voice shook with excitement as he radioed the sighting.

To the Italians, the message would seem like a chance encounter. To the British, it was the perfect cover story—a convenient “accident” that explained how their fleet would soon be in position to meet the enemy head-on, without betraying Bletchley Park’s secret.

When the report reached Admiral Cunningham in Alexandria, he read it in silence. Tall, spare, and sharp-eyed, Cunningham was a man of precise habits and unshakable calm. He’d spent decades studying the sea, and he understood instinctively that wars were won not by force alone, but by timing, deception, and nerve. The Italians thought he was idle. Let them think it. He would let them sail straight into a trap of his own design.

In the afternoon, as the Mediterranean sun began to fade, Cunningham did something that would become legend. He arrived at the Alexandria Sporting Club carrying a small suitcase. There, in full view of society’s eyes, he chatted with acquaintances, shook hands, and even exchanged pleasantries with the Japanese consul—a man known to be an informant for Axis intelligence. Cunningham laughed easily, ordering a drink and mentioning casually that he planned to spend the evening at the club. “A quiet night,” he told one of the officers nearby. “No reason to hurry back to the harbor.”

It was a performance worthy of the theater. The consul, eager to deliver fresh intelligence, immediately cabled the information to his contacts. Within hours, German and Italian intelligence were convinced that the British commander was still on shore, far from his fleet, utterly unprepared. The deception was complete.

But when night fell, the illusion crumbled. As the city of Alexandria slept, Cunningham quietly excused himself from the club, slipped through a back entrance, and made his way to the naval base. There were no parties aboard his flagship HMS Warspite—only silence, tension, and purpose.

By 2300 hours, the Mediterranean Fleet was awake and alive. Across the harbor, the great warships stirred. Floodlights dimmed. Dockhands worked in whispers. One by one, the battleships Warspite, Valiant, and Barham eased away from their moorings, followed by the aircraft carrier Formidable and a screen of destroyers. Their wakes glowed faintly in the moonlight as they slipped through the harbor mouth and out into open water.

The sea was black and calm, the sky vast and starless. Engines throbbed deep below decks, steady and rhythmic. Men stood at their posts, faces lit only by the soft glow of instrument panels. In the distance, Alexandria’s shoreline receded into a faint smear of yellow light. The fleet moved in silence—no radio chatter, no signal lamps, no trace of its presence.

And far to the north, Admiral Iachino’s armada steamed forward under the same night sky, unaware that their movements, their formation, and even their timing were already known to the enemy.

Somewhere between the two fleets, the fate of the Mediterranean—and the lives of thousands of sailors—hung in the balance.

The trap was set. The hunters were closing in on each other. And neither side yet understood just how completely one nineteen-year-old woman had rewritten the rules of the war at sea.

Continue below

March 1941. The Mediterranean shimmered beneath the late winter sun, a vast, deceptive mirror stretching between Europe and Africa. The water lay calm, quiet, and cold — but beneath its silver surface, two great fleets were preparing to decide the fate of an empire. In the heart of the Italian command, Admiral Angelo Iachino stood aboard his flagship, the battleship Vittorio Veneto, a vessel as imposing as the nation that built it. The pride of Mussolini’s navy, she was a symbol of fascist power: nine 15-inch guns, armor thick as castle walls, and speed that could outpace any British capital ship afloat. Iachino was confident, even pleased. The latest intelligence reports told him the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean commander, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, was in Alexandria, playing golf. British merchant convoys were moving to Greece, undefended and ripe for destruction.

Iachino smiled thinly as he leaned over the plotting table in the battleship’s operations room. His officers hovered around, crisp uniforms and polished boots gleaming in the reflected light from the sea. “Cunningham has no idea,” he said softly. “We will strike before the British even leave their harbors.” Around him, the atmosphere brimmed with anticipation — the kind that precedes triumph. For months, the Regia Marina had lived in the shadow of the British Royal Navy, their ships fast and modern but too often hesitant, too often beaten back by intelligence leaks or British aircraft. This time, the tables would turn.

Then came even better news. At 0600 hours, Iachino’s reconnaissance pilots reported sighting four British light cruisers and several destroyers in the Aegean Sea, heading northwest. Four cruisers — a small force, perhaps protecting convoys. A perfect target. Iachino’s eyes lit up. “We will destroy them,” he said. “The British will learn what the Italian Navy can do.” His 22-vessel armada — battleships, heavy and light cruisers, and destroyers — turned toward the coordinates. Orders were shouted, flags hoisted, and engines roared to life. As Vittorio Veneto cut through the water at thirty knots, white spray erupted from her bow like smoke from a charging bull.

But while the Italian admiral believed he was the hunter, he was, in truth, already the prey.

Hundreds of miles away, in a quiet countryside mansion northwest of London, a young woman named Mavis Batey sat hunched over a cluttered desk at Bletchley Park, the British codebreaking center. The room was thick with cigarette smoke and the rhythmic clicking of typewriters. Sheets of intercepted Italian naval traffic lay before her — long columns of meaningless letters, encrypted by the Italian variant of the Enigma machine. The best cryptanalysts in Britain had failed to break it. But Mavis, barely nineteen years old, possessed an unshakable intuition and a mind sharpened by patience. That morning, acting on a hunch, she made a tiny adjustment to her search pattern. It was a guess — a breach of protocol — but within moments, something miraculous happened. The meaningless letters began to rearrange themselves into words.

She stared in disbelief. The message was brief and cryptic: “Today’s the day minus three.”

Her pulse quickened. “Minus three… what?” she murmured. Hours later, the meaning clicked into horrifying clarity when another intercepted message arrived: a major Italian naval operation was about to begin — an attack against British convoys carrying troops and supplies to Greece. The Italian fleet would sail from Taranto and head east. For the first time, the Royal Navy had eyes inside the enemy’s mind. The codebreakers had just handed Admiral Cunningham the most precious weapon of war: foreknowledge.

But there was a danger. If the Italians realized their codes had been broken, they would change the system instantly, erasing Britain’s advantage. Cunningham could not act in a way that revealed he already knew of the attack. So British intelligence devised a deception. A Short Sunderland flying boat, disguised as if on a routine patrol, was ordered to “discover” the Italian fleet — purely by chance. Its pilot, unaware of the greater plan, genuinely believed he’d stumbled upon the sighting of a lifetime when, seventy-five miles east of Sicily, he looked down through the clouds and saw steel glinting like silver fish in formation: the Vittorio Veneto and her escorts — Zara, Fiume, Pola, Trento, Trieste, Bolzano, Garibaldi, and Abruzzi, plus thirteen destroyers. Twenty-two ships in all.

The pilot’s excited report reached British headquarters as though it were random reconnaissance. In reality, it was a perfect smokescreen — one that protected the secret of Bletchley Park’s success and set in motion the deadliest trap of the Mediterranean war.

In Alexandria, Cunningham received the decrypted intelligence in silence. A thin, hawk-faced man, he studied the situation with methodical calm. He knew the Italians believed him idle. That was part of the deception. “If they think I’m playing golf,” he muttered, “let them think it.” But in private, orders flashed across the harbor. Crews were recalled, engines fired up, and ammunition loaded. The Mediterranean Fleet was preparing to sail. Cunningham understood that this operation would require flawless coordination and absolute secrecy.

To make the illusion perfect, he went to extraordinary lengths. On the afternoon of March 27th, he arrived at the Alexandria Sporting Club carrying a suitcase, making sure to be seen by the Japanese consul — an unofficial German ally and habitual informant. Cunningham smiled, chatted with acquaintances, and loudly announced he would be staying overnight. He even booked a party aboard his flagship HMS Warspite for that evening. The consul dutifully reported everything. By dusk, the Germans — and through them, the Italians — were convinced the British admiral was still on shore, playing golf, oblivious to the Mediterranean’s unfolding drama.

But when night fell, the masquerade ended. Cunningham quietly left the club and slipped into the naval base under cover of darkness. No parties awaited aboard Warspite — only war. By 2300 hours, the great ships of the Royal Navy began sliding silently from their moorings, one after another. The battleships Warspite, Valiant, and Barham, the aircraft carrier Formidable, and their destroyer escorts all turned their prows toward the open sea. In the black Mediterranean night, their engines throbbed like heartbeats of steel. The world above slept; below, history was moving.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, Admiral Iachino’s fleet steamed eastward, unaware of the invisible eyes tracking every movement. The Italians were confident. The Vittorio Veneto was the most powerful battleship in the Mediterranean — faster and more heavily armed than anything the British could field. But for all her power, she was blind. Italian ships lacked radar. Their gunners fired by eye and instinct, guided by rangefinders that were all but useless in darkness or haze. Worse, the air cover promised by the German Luftwaffe never materialized. Only two Junkers Ju 88 bombers circled overhead — a pitiful escort for an entire armada.

Still, Iachino pressed on. He had no choice. The Germans were pressuring Mussolini to support the coming invasion of Greece, and a decisive naval victory was essential to Italy’s prestige. The admiral stood on Vittorio Veneto’s bridge, his cap gleaming under the Mediterranean light, as his fleet sliced through the sea at thirty knots. “We will destroy their convoys,” he told his officers, unaware that Cunningham had already diverted those convoys to safety. The British merchant ships were long gone. Only warships now remained in the area — bait, floating in open water, waiting to be found.

At dawn on March 28th, the trap began to close. Admiral Cunningham had dispatched Vice Admiral Henry Pridham-Wippell ahead with a decoy force: four light cruisers — Ajax, Orion, Gloucester, and the Australian HMAS Perth — accompanied by four destroyers. Their mission was to find the Italians and then run, drawing them southward into the waiting jaws of the British battle line approaching from Alexandria. It was a dangerous job, and Pridham-Wippell knew it. His ships were outgunned and outnumbered, but their role was not to fight — it was to lure.

At 6:35 a.m., the first Italian reconnaissance plane spotted the British cruisers. The report reached Vittorio Veneto swiftly. Iachino’s reaction was immediate. “An unexpected gift,” he said. “A handful of British cruisers — alone, exposed. We will crush them before they escape.” He ordered his 3rd Cruiser Division — Trieste, Trento, and Bolzano — to intercept. At 8:12 a.m., their 8-inch guns opened fire from 24,000 yards, thunder rolling across the sea.

The British returned fire, smaller guns flashing defiantly. Shells splashed between the ships, columns of water rising like pillars. Though the Italians had superior range, their gunnery was inconsistent, shells falling short or wide. The British, agile and precise, zigzagged under the barrage. Their radio operators calmly reported positions back to Cunningham, who by now was racing north with his battleships. Every minute the Italians spent chasing, every round they fired, brought them closer to destruction.

Then, at 10:55 a.m., a shadow appeared on the horizon. On the bridge of HMS Orion, an officer spotted it first. “What’s that battleship over there?” he asked. “I thought ours were miles away.” It was not a British ship. It was Vittorio Veneto. Iachino’s flagship had maneuvered into position to cut off the retreat. The British cruisers were trapped between her and the oncoming Italian cruisers — a deadly pincer.

Vittorio Veneto’s guns thundered to life, each shell nearly a ton of steel and explosive. In twenty-nine salvos, she fired ninety-four rounds. The sea erupted in chaos. Massive water spouts engulfed Orion and Gloucester, shrapnel ripping across their decks. Men were thrown from their posts, radios shattered, splinters slicing through steel. It seemed impossible that they could survive another hour. But then came the sound that changed the battle — the low hum of engines in the sky.

At 11:00 a.m., six Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers from HMS Formidable appeared over the horizon. They dived through anti-aircraft fire, their slow wings glinting in the sunlight. Italian gunners opened up, the sky turning into a storm of tracers. The Albacores released their torpedoes — none hit their mark, but the attack forced Vittorio Veneto into violent evasive maneuvers, throwing off her aim and breaking the rhythm of her fire. The British cruisers escaped southward, smoke trailing from their funnels.

For Iachino, the brief triumph had turned sour. He had nearly destroyed four British cruisers, but his fleet was scattered and vulnerable, and now, he suspected, under air surveillance. “We are walking into a trap,” he muttered. He gave the order to turn west, to retreat. Vittorio Veneto’s engines roared to full power. The Italians began their desperate flight home.

But the British were not done. In the skies above, another wave of Albacores from Formidable prepared for a second strike, their torpedoes gleaming like silver spears. Among them was Lieutenant Commander John Dalyell-Stead, leading his men in what would become one of the most daring attacks of the Mediterranean war.

As his aircraft descended through flak and smoke, Dalyell-Stead saw the Italian flagship below him — immense, majestic, and unaware of the doom streaking toward her through the waves. He pressed in to point-blank range, releasing his torpedo barely a thousand yards from Vittorio Veneto’s hull. Seconds later, a deafening explosion ripped through the battleship’s side. Water rushed in. The ship shuddered, her port propeller shaft jammed, and she lurched to a stop, dead in the water.

But victory came at a price. Dalyell-Stead’s Albacore, riddled with shrapnel, spiraled downward, crashing into the sea. He and his crew were killed instantly.

Aboard Vittorio Veneto, engineers fought desperately to save her. Pumps roared. Bulkheads sealed. After agonizing minutes, they managed to restart the engines. The ship moved again — but slower, wounded, bleeding oil into the sea. The British had struck deep. Now, Cunningham was closing in.

As the sun began to fade behind the western horizon, the battle had shifted from daylight pursuit to nocturnal reckoning. The Italians raced for home, unaware that the night itself now favored their enemy — an enemy armed not only with battleships and courage, but with the cold precision of radar and a plan born from a young woman’s mind at a desk in Bletchley Park.

And in that approaching darkness, the deadliest trap of the Mediterranean was about to spring shut.

The Mediterranean night descended like a black curtain, swallowing the horizon as if the sea itself wished to erase the day’s violence. The Italian fleet, once so confident, now fled westward in a column of steel and desperation. The great Vittorio Veneto, once the pride of Mussolini’s navy, steamed at reduced speed — her engines groaning from the torpedo wound inflicted by Lieutenant Commander John Dalyell-Stead’s final act of courage. Oil bled into the sea from her damaged hull, spreading across the surface like a dark shroud. Admiral Angelo Iachino stood rigid on the bridge, hands clasped behind his back, his face pale beneath the red glow of the chart lamps. The admiral knew the British were pursuing, but he clung to hope. If his fleet could reach Taranto by dawn, safety awaited.

But the trap had already been sprung. Miles to the south and east, the British Mediterranean Fleet surged forward under cover of darkness. Warspite, Valiant, and Barham plowed through the rolling black waves, their bow waves shimmering faintly under the dim light of the moon. The carrier Formidable sailed astern, her flight deck empty now — the torpedo bombers were gone, many damaged, some destroyed. Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell’s cruiser force had rejoined the main fleet, their mission of baiting the Italians complete. In the darkened flag bridge of Warspite, Admiral Andrew Cunningham leaned over a plotting table, his voice calm but resolute. “They’ve taken the hook,” he said quietly. “Now let’s see if we can reel them in.”

Cunningham was not a man given to emotion. His officers often said his strength lay in the steadiness of his hand — the ability to make decisions under crushing uncertainty. But even he could not deny the thrill coursing through his veins. The operation had unfolded exactly as planned: the codebreakers at Bletchley Park had given him knowledge of every Italian movement; his cruisers had drawn the enemy into pursuit; and now, radar — Britain’s new invisible weapon — was about to finish what intelligence and courage had begun. The enemy had no idea that in this new kind of war, darkness no longer offered safety.

As midnight approached, the situation aboard Vittorio Veneto deteriorated. Her crew had managed to restore partial power, but the great ship could no longer maintain full speed. Engineers in the engine rooms worked waist-deep in oily water, the air choking with smoke and steam. Pumps clattered, men shouted, and all the while, the sound of distant thunder — the reverberation of British propellers — grew faintly louder. “Increase speed to nineteen knots,” Iachino ordered. “We must make Taranto by dawn.” His officers obeyed without hesitation, though many now doubted whether they would ever see home again.

Behind them, the Italian cruisers and destroyers followed in loose formation. The heavy cruiser Pola lagged behind, still crippled by an earlier torpedo strike that had left her dead in the water. On her decks, Captain Manlio De Pisa faced an impossible choice. He gathered his officers and spoke plainly. “Gentlemen, we are adrift. If the enemy finds us, we cannot fight, and we cannot flee. Those who wish to die as heroes may remain aboard. Those who wish to see their families again, take to the boats. Long live Italy.” His voice, weary yet steady, carried over the crackling of flames and the hiss of escaping steam. Some men stayed at their stations, gripping rifles and machine guns; others climbed into lifeboats, pushing away into the dark, the phosphorescent glow of the water trailing behind them like ghosts.

Aboard Vittorio Veneto, Iachino received word of Pola’s condition. His jaw tightened. Leaving her meant condemning nearly a thousand sailors to death or capture. But sending help could expose the rescuers to enemy attack. After a long pause, he made the decision that would doom his fleet. “We do not abandon our own,” he said firmly. “Order Admiral Cattaneo to turn back. He will take Zara, Fiume, and four destroyers. They will tow Pola to safety.” The signal was sent. Aboard Zara, Admiral Carlo Cattaneo acknowledged the message and immediately altered course. His squadron turned east, steaming directly toward the stationary Pola — and into the jaws of the British fleet.

By 10:00 p.m., the British had closed to within striking distance. In the radar room of HMS Valiant, a young operator watched the green glow of the screen pulse rhythmically. Then he saw it — a faint echo, six miles off the port bow. He leaned toward his commanding officer. “Contact bearing zero-eight-five, sir. Large surface vessel, stationary.” The officer nodded and relayed the information up the chain of command. Within minutes, the entire British line knew: they had found Pola. Cunningham smiled grimly. “Right where we expected her.”

The admiral’s plan crystallized. Pola was the bait; the rest of the Italian squadron would soon come to rescue her, unaware that three British battleships — each bristling with fifteen-inch guns — waited in ambush. The sea was perfectly still, the night utterly black. Radar gave the British eyes; the Italians, blind and trusting in the darkness, advanced straight into annihilation.

“Maintain silence,” Cunningham ordered. The British ships glided through the water like shadows. Below decks, gun crews stood ready, hands on shell hoists, every muscle tense. The battleships’ engines throbbed low and steady. In the flag bridge of Warspite, the tension was so thick that no one spoke above a whisper. They all knew what was coming.

At 10:25 p.m., Valiant’s radar picked up new contacts — multiple ships approaching from the northwest. The operator called out distances as they closed: eight miles… seven… six… five. It was Cattaneo’s rescue force — Zara, Fiume, and four destroyers — steaming in perfect line ahead, their searchlights dark, their crews unaware. Cunningham’s destroyer captains requested permission to attack first with torpedoes, as doctrine demanded. But visibility was poor, and the exact positions of the Italian ships uncertain. Cunningham made his decision instantly. “No,” he said. “The battleships will open fire. Range is close enough for direct hits.”

At 10:30 p.m., the order was given. The British battle line turned slightly to starboard, bringing all main guns to bear. The crews stood by, hearts pounding. Searchlights snapped on, blazing through the night, and in that instant, the Italian ships were revealed — enormous, elegant silhouettes suddenly trapped in blinding light. Aboard Valiant, one of the men operating the searchlights was a 19-year-old royal navy midshipman: Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, the future Duke of Edinburgh. His beam caught Fiume square amidships, illuminating her from bow to stern.

For a heartbeat, there was silence. Then the Italians, believing the lights came from friendly ships, fired recognition flares. A few even waved. The illusion lasted only seconds.

“Open fire,” Cunningham commanded.

The Mediterranean exploded.

Warspite’s six 15-inch guns thundered as one, spitting flame and smoke that lit the sky for miles. Valiant and Barham followed, their broadsides tearing through the night like rolling thunder. Each shell weighed nearly a ton, and at point-blank range — less than 3,000 yards — every hit was catastrophic. The first salvo struck Zara, smashing her forward turrets and ripping open her decks. A second hit ignited her fuel stores, sending a tower of flame hundreds of feet high. Fiume took the next barrage — one shell punched through her bridge, killing Admiral Cattaneo instantly, another hit her ammunition magazines. The explosion was so violent that witnesses aboard Warspite described the cruiser as “disappearing into a mane of shearing flame.”

Within minutes, both heavy cruisers were crippled, burning from stem to stern. The destroyers Alfieri and Carducci, charging forward in a desperate attempt to retaliate, were shredded by secondary gunfire. One destroyer’s torpedoes detonated prematurely, engulfing her in fire. The other broke apart under the sheer concussive force of the British barrage. The sea turned orange with reflected firelight.

Aboard Warspite, Cunningham stood motionless, watching the destruction through his binoculars. His officers, hardened by years of naval combat, were stunned. “Never in my life,” Cunningham later wrote, “have I experienced a more thrilling moment.” Yet even amid the triumph, the admiral felt no joy — only awe at the sheer devastation wrought in so few minutes.

The British battleships fired 100 rounds in less than five minutes. When the smoke began to clear, only twisted, flaming wrecks remained where proud Italian cruisers had sailed. Some ships were still afloat, their crews leaping into the sea to escape the inferno. Oil spread across the water, igniting into patches of fire that drifted with the current. The cries of hundreds of sailors echoed through the darkness.

Even in victory, Cunningham’s instincts as a seaman — and as a human being — took over. “Signal the destroyers,” he ordered quietly. “Begin rescue operations.” Orders rippled through the fleet, and British sailors lowered boats into the water, risking their lives to save their enemies. One survivor, Giuseppe Anzevino from Pola, later described the surreal kindness he received: “I was given a cup of hot tea. It was a great help because there was no meal aboard, but I was also given a piece of white bread — as white as milk — and it was the first time I saw it.”

By 2:00 a.m., the shooting had stopped. The sea was littered with debris, flames, and hundreds of men struggling to stay alive. The British destroyers moved among them, hauling the wounded aboard, offering blankets and water. Then, at dawn, the sound of approaching aircraft reached their ears — German dive bombers, dispatched too late to save the Italian fleet but soon enough to threaten its destroyers. Cunningham, unwilling to risk his ships further, reluctantly gave the order to withdraw.

Before leaving, he did something extraordinary. Over open international radio frequencies, he transmitted a message in clear Italian: “Have been endeavoring to pick up your survivors from last night’s action, but forced to abandon them due to heavy bombing attacks. If you send fast hospital ship… it will be given safe conduct.” It was an act of compassion rare in modern war. Hours later, the Italian hospital ship Gradisca arrived, her white hull gleaming in the sunlight, and rescued another 160 men from the wreckage of their fleet.

By daybreak, the scale of the disaster was clear. Two heavy cruisers — Zara and Fiume — lay at the bottom of the sea. Pola would soon follow, scuttled by British torpedoes before dawn. Two destroyers were gone. Over 2,300 Italian sailors were dead or missing. In contrast, the British losses amounted to three airmen — Lieutenant Commander Dalyell-Stead and his crew, who had died striking the first blow against Vittorio Veneto.

The Battle of Cape Matapan, as it would later be known, was more than a tactical victory. It was a turning point — a demonstration that the age of radar, codebreaking, and night fighting had begun. For Italy, it was humiliation; for Britain, vindication. Cunningham’s daring, combined with Bletchley Park’s brilliance, had turned the Mediterranean from a battleground into a British lake.

In the aftermath, Mussolini raged, the Italian navy retreated to its ports, and the balance of the war at sea began to tilt irreversibly toward the Allies.

And in the quiet rooms of Bletchley Park, far from the gunfire and the flames, Mavis Batey folded her decoded sheets into a file, unaware that her small act of defiance — one line of adjustment on a machine — had just reshaped the course of naval history.

By the time the sun rose over the Aegean on March 29, 1941, the blue waters of the Mediterranean were still streaked with the soot and oil of battle. The sea was eerily calm, as if exhausted by the violence of the night before. Smoke hung low across the horizon, drifting over the remains of what had been one of Italy’s proudest naval formations. Lifeboats bobbed among debris—splintered wood, half-submerged lifebuoys, and twisted metal torn from ships that had once embodied Mussolini’s dreams of maritime glory.

Admiral Angelo Iachino stood at the railing of Vittorio Veneto, staring into the gray dawn. His great battleship was alive but limping, her hull still leaking oil, her crew bone-tired. The reports from his rear guard had stopped coming hours ago. No word from Admiral Cattaneo. No confirmation that Zara, Fiume, or Pola had escaped. The silence told its own story. He didn’t need confirmation to know the truth. The 1st Cruiser Division was gone. Destroyed. Thousands of sailors lost in one night.

He removed his cap and rubbed his temples, the weight of failure pressing like a stone on his chest. “How could it happen?” he murmured, his voice barely audible over the hum of the engines. Around him, his officers said nothing. They had all seen the flashes of distant explosions during the night, the flickering horizon that told of a massacre. None dared speak the words that hung in every mind: the Royal Navy had found them, struck without warning, and annihilated an entire division before they could fire a single effective shot.

Aboard Vittorio Veneto, the mood was somber, even funereal. Sailors moved quietly through the corridors, repairing damage where they could, cleaning away soot, tending to wounded men. Every clang of metal and hiss of steam carried an undertone of disbelief. How had their modern fleet—fast, powerful, beautifully engineered—been reduced to this? They had trained for daylight gunnery duels, for battles fought under the sun with clear visibility and honor. But last night had been something else entirely. The enemy had attacked from the dark, unseen and unstoppable. The British had fought a different kind of war—one guided by machines, radar, and uncanny foresight.

As the fleet limped home, the full scope of the disaster became clear. Zara, Fiume, Pola, Alfieri, and Carducci—gone. Over 2,300 men killed. Admiral Cattaneo, dead with his ships. Only a handful of survivors would live to tell what happened. The battle would later be called the Tragedy of Matapan, and it would haunt the Italian navy for the rest of the war.

Far to the south, aboard the British flagship HMS Warspite, the contrast could not have been greater. The men were exhausted, but the mood was electric. They had witnessed something no naval crew had seen since the days of Nelson—a perfect ambush, a one-sided victory so absolute it was almost difficult to comprehend. The sea, now calm and blue once more, hid the scale of what had occurred beneath its surface. Admiral Andrew Cunningham stood on the bridge, hands clasped behind his back, staring toward the east where smoke still hung faintly in the sky.

Around him, the deck was alive with murmurs of awe. Officers spoke in hushed tones, almost reverently, about what they had seen. Some were exhilarated, others shaken by the sheer destruction they had unleashed. Cunningham, though, remained composed. He had seen enough war to know that triumph and tragedy were often separated by a razor’s edge. He turned to his chief of staff, Captain Power, and said quietly, “It’s over. We’ve done what we came to do. Signal all ships—well done, and withdraw.”

Moments later, a signalman hoisted flags into the breeze: ‘Operation complete. Return to base.’ Across the fleet, weary sailors cheered, their relief echoing over the waves. Many had fought for hours in near darkness, their faces smeared with soot and salt. Some leaned against the rails, staring into the water as if trying to make sense of what they had survived.

But Cunningham’s satisfaction was tempered by the images still vivid in his mind: the burning hulks, the cries of drowning men, the brief flash of recognition on the faces of Italian sailors who had realized, too late, what was happening. For all his professionalism, Cunningham was not immune to reflection. “I would rather sink ships than men,” he said quietly to his adjutant that morning. “But the two are rarely separate in war.”

Back in Alexandria, word of the victory spread quickly through the fleet headquarters. Telegraph operators barely kept up with the flood of coded messages coming in from Warspite. The Mediterranean Fleet had done the impossible—it had annihilated a superior Italian force with minimal losses. But it was not brute strength or luck that had carried the day; it was intelligence, coordination, and nerve. The operation had been built on deception, secrecy, and a single moment of insight by a young woman in a country estate thousands of miles away.

At Bletchley Park, Mavis Batey was still awake when the telegram arrived. The message was brief but unmistakable: ‘Enemy fleet destroyed. Matapan success complete.’ She read it three times before setting it down, her heart pounding. Around her, the other codebreakers in Hut 4 exchanged tired smiles and quiet congratulations. They all knew what it meant. Their work—painstaking, invisible, and secret—had just saved thousands of British lives and secured the Mediterranean.

Mavis leaned back in her chair, rubbing her eyes. She could picture the map of the sea she had studied for weeks, the routes of convoys and fleets, the coded signals she had helped decipher. Each letter, each number, had been part of a chain leading to that night’s victory. She thought of the Italian sailors who had gone down with their ships, men she had never met, whose deaths had been sealed by her own discovery. The feeling was complex—pride, relief, and a deep, quiet sadness. “We won,” she said softly. “But they’ll never know how.”

Three weeks later, Admiral Cunningham visited Bletchley Park in person. The visit was unannounced and classified. Mavis and the others were gathered in a narrow corridor when the tall, broad-shouldered admiral walked in, his uniform immaculate, his face weathered but kind. He thanked each of them personally. “You gave us the key,” he told Mavis, shaking her hand. “Without your work, we’d have walked into their trap. Instead, we turned it on them.”

She smiled nervously, unsure what to say. The admiral’s voice softened. “Remember this, Miss Batey—battles may be won at sea, but wars are won in rooms like this.” Then he was gone, leaving behind an office of stunned silence. For a brief moment, the men and women of Bletchley Park allowed themselves a rare moment of pride.

While the British celebrated quietly, the reaction in Italy was one of shock and denial. In Rome, the news was suppressed for days before Mussolini finally received the full report. When he did, witnesses later said his fury was volcanic. He raged against his admirals, accusing them of cowardice, incompetence, and betrayal. “How could this happen?” he shouted. “You had the finest ships! The fastest! The most powerful guns! And yet you let them slaughter you like fish in a barrel!”

The truth, though, was simpler and far more devastating. Italy’s fleet had not been destroyed by inferior ships or poor courage—it had been undone by a kind of warfare it did not yet understand. Radar. Codebreaking. Night tactics. Intelligence. The British had fought with foresight while the Italians had fought with tradition, and the difference was fatal.

In Taranto, the surviving sailors of Vittorio Veneto disembarked in silence. Families waited on the docks, searching the faces of returning men for loved ones who would never come home. The wounded were carried ashore on stretchers, the band of the Regia Marina playing softly, as if to drown out the questions no one dared to ask. Iachino submitted his report to the Naval Staff the next day. It was terse and formal, written in the restrained language of military defeat: “Enemy action during night hours resulted in heavy losses. The engagement demonstrated deficiencies in equipment and doctrine.” But privately, he knew the truth: he had sailed into a trap of his own making.

British newspapers, meanwhile, carried the news on their front pages within days. “ITALIAN FLEET SHATTERED—ADMIRAL CUNNINGHAM’S MASTERSTROKE AT CAPE MATAPAN.” The headlines praised the Royal Navy’s daring, the heroism of its sailors, and the ingenuity of its command. But what the public never learned—what would remain secret for decades—was the role of Bletchley Park and the invisible war that had made the victory possible.

In London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill received Cunningham’s full after-action report with deep satisfaction. “This,” he told his aides, tapping the dispatch with a cigar-stained finger, “is what happens when brains and courage fight together.” He ordered that Cunningham’s success be broadcast to every Allied fleet, calling it “a victory worthy of Trafalgar.”

Cunningham, for his part, refused to revel in it. In his private notes, he wrote: “Matapan was a triumph of teamwork—of sailors, airmen, and the unseen men and women of intelligence. It was also a tragedy for the enemy, whose courage deserves our respect. War is not about hate; it is about endurance.”

For the Italian navy, Cape Matapan marked the end of its ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean. Never again would the Regia Marina venture far from its home ports. The psychological wound was as deep as the strategic one. Every admiral knew that the British could now see in the dark, hear in silence, and strike without warning. The fear of radar and codebreaking became an obsession that haunted Italian command rooms until the end of the war.

In Britain, though, the lessons of Matapan were studied intensely. The victory validated every penny spent on radar research and codebreaking. It proved that the future of naval warfare would belong to those who could combine intelligence with speed and precision. No longer would navies fight blindly. Information—not armor, not guns—was now the decisive weapon.

And so, even as the sea returned to calm and the smoke of battle faded into history, the echoes of Cape Matapan continued to ripple across the world. It was not merely a battle; it was the death of one era and the birth of another.

The months following the Battle of Cape Matapan passed quietly, at least on the surface. The Mediterranean seemed to settle into uneasy stillness, the waters deceptively calm, masking the invisible war still raging beneath its waves and across radio frequencies. To the casual observer, it appeared as though the Royal Navy’s dominance had returned unchallenged, but within the command centers of both Britain and Italy, the consequences of that March night continued to unfold in ways that would shape the rest of the Second World War.

For Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the victory was both vindication and burden. He had achieved what many considered impossible: destroying a larger, modern enemy fleet in a single night with minimal British casualties. In his official dispatches, he attributed the success to discipline, training, and the courage of his men. But in private, he knew the truth ran deeper. Without radar, without Bletchley Park, without the invisible hands decoding enemy intentions, Matapan could have easily ended in disaster. It was a triumph of intellect as much as gunnery—a battle not only fought, but foreseen.

In Alexandria, the Mediterranean Fleet resumed its constant rhythm: convoys escorted to Malta, raids on Axis shipping, and long stretches of tense silence at sea. Yet among the sailors, Matapan became legend. They spoke of it in low voices, as if recounting a ghost story—of how, in one moonless night, British ships had crept through the darkness and annihilated an enemy fleet at point-blank range. Many who had seen it with their own eyes struggled to describe the magnitude of the destruction. “It wasn’t a battle,” one petty officer later said. “It was an execution.”

Cunningham, though proud, carried the memory differently. Each time he looked at the Mediterranean horizon, he remembered the cries of men in the water—their faces illuminated by the fire of their sinking ships, the way some had waved, believing the British lights were signals of rescue rather than doom. “We must never take pleasure in slaughter,” he told his flag officers after the battle. “Victory is our duty. Mercy is our measure.”

The admiral’s respect for his adversary only deepened when he read the intercepted Italian reports in the weeks that followed. The dispatches, grim and precise, detailed the loss of life with an almost stoic restraint. In his diary, Cunningham wrote: “The Italians fought bravely, but they were blind in a world that demanded sight. They had courage, but no radar. Discipline, but no knowledge of their enemy’s mind.”

That “knowledge of the enemy’s mind” was what had truly won Matapan—and it came not from admirals or airmen, but from a nineteen-year-old woman working at a wooden desk in Buckinghamshire.

At Bletchley Park, the work never stopped. Mavis Batey and her colleagues in Hut 4 continued decoding Italian and German naval signals, their small victories measured in words and numbers, never in headlines. They were forbidden to speak of their success at Matapan, even to family. But the knowledge of what they had done—what Mavis had helped set in motion—lingered like an ember. Each time a new intercept arrived, each time another Enigma key fell, she remembered the night when their intelligence had turned the tide of an entire theater of war.

She thought often of the Italian sailors who had died, the ones whose orders she had read in code before they even knew them themselves. In her diary, she wrote: “The war at our desks feels bloodless until we hear what becomes of our work. Then it is like a shadow passing through the room. We see the cost, even if we cannot speak of it.”

In Italy, that cost was everywhere. Taranto’s naval base became a graveyard of silence. Hundreds of widows waited for word that never came, clutching photographs of sons and husbands lost off Cape Matapan. Black flags hung from balconies; chapels filled with the scent of candle wax and grief. The Regia Marina, once proud and defiant, withdrew from open operations in the eastern Mediterranean. Its ships, still formidable on paper, now stayed close to port—anchored under the protection of airfields and coastal guns.

The Italian naval staff convened inquiry after inquiry, but no investigation could explain away the unexplainable. Admiral Iachino submitted his report with professional restraint, but he could not hide his frustration. “Our equipment was obsolete,” he wrote. “Our doctrine, outdated. We fought men who saw through the night.” He had meant it literally and figuratively.

Radar had changed everything.

Within months, the British Admiralty made radar a mandatory installation on all major warships. The lessons of Matapan spread through every fleet, every command room. Night fighting—once considered reckless—was now doctrine. The Royal Navy trained relentlessly, honing tactics that relied not on sight, but on signal. For the first time, battles at sea were being guided by invisible lines of radio energy and invisible hands of cryptographers.

In Germany, the shockwaves reached as far as Berlin. Naval intelligence quickly concluded that the British had possessed uncanny foreknowledge of the Italian fleet’s movements. “It is possible,” one Abwehr report noted, “that the Enigma system has been compromised.” But the claim was dismissed. The Germans believed their version of Enigma—far more complex than the Italian adaptation—was unbreakable. That assumption would cost them dearly before the war’s end.

Back in Rome, Mussolini’s pride was wounded beyond repair. He publicly praised the heroism of the fallen, declaring them “martyrs of Fascist glory,” but in private, his confidence in his admirals evaporated. He tightened German oversight of Italian operations, effectively placing the Regia Marina under the shadow of the Kriegsmarine. Italian officers spoke of “the night of shame,” and younger sailors whispered bitterly that they had been sent to die without eyes or ears.

Yet even amid defeat, there were acts of extraordinary humanity that transcended the bitterness of war. Survivors pulled from the sea by the British told stories that astonished their countrymen. They described being given blankets, hot tea, and bread by the same men who had destroyed their ships. One officer, rescued from the burning wreck of Zara, wrote later in his memoir: “In the face of death, our enemies showed us the decency our own leaders denied us. I realized then that war can destroy ships but not always honor.”

The British, too, were changed by the experience. In the weeks after Matapan, sailors who had taken part in the rescue spoke often of the faces they had seen in the water—the confusion, the disbelief, the humanity of it all. For many, it was the first time they had looked directly into the eyes of the men they were told to hate. “We expected devils,” one seaman recalled. “But they looked just like us—tired, scared, praying for the same mercy we’d want in their place.”

Cunningham never forgot those words. He would later say that Matapan had taught him two things: that courage alone was not enough to win modern war, and that compassion was never weakness. His actions in broadcasting the survivors’ coordinates to the Italians, ensuring the hospital ship Gradisca could reach them safely, would be remembered as one of the most humane decisions of the naval war.

When Cunningham was later promoted to Admiral of the Fleet, Churchill himself commended him for “combining brilliance in victory with decency in its aftermath.” But the admiral always redirected the praise. “If there is credit to be given,” he once told a gathering of officers in London, “it belongs to those who gave us the advantage—the unseen, the unheard, and the uncelebrated.” It was his nod to Bletchley Park, though even then, the name could not be spoken aloud.

The legacy of Cape Matapan rippled far beyond 1941. It marked the end of Italy’s dominance in the Mediterranean, ensuring British control of the sea lanes to Greece, Crete, and North Africa. It allowed the Allies to sustain their campaigns across the Middle East and protect vital supply routes through the Suez Canal. But perhaps more importantly, it marked the dawn of a new kind of warfare—one fought not only with ships and guns, but with signals, codes, and information.

Years later, when the secrets of Bletchley Park were finally revealed, historians would see Matapan as one of the first battles truly won by intelligence. The young codebreakers, the radar technicians, the pilots who braved flak and darkness—all had worked together in ways the world had never seen before. It was the blueprint for the Allied victories that would follow: El Alamein, Midway, Normandy.

And through it all, one lesson endured. The sea may be vast and unfeeling, but wars are still fought—and won—by human hands and human minds.

In her old age, long after the war, Mavis Batey was once asked how she felt knowing that her discovery had led to such loss of life. She paused before answering, her eyes distant, her hands folded in her lap. “It isn’t pride I feel,” she said finally. “It’s gratitude. Gratitude that I was able to save lives on our side, and sorrow for the ones who couldn’t be saved on theirs. That’s war, isn’t it? Every victory is someone else’s heartbreak.”

The Battle of Cape Matapan remained one of the most lopsided naval victories of the Second World War. Three thousand Italian casualties against three British. A single night that silenced the Regia Marina, secured the Mediterranean, and proved once and for all that the era of battleships alone was ending. In its place rose a new empire—an empire of intelligence, of radar screens and radio waves, of minds like Mavis Batey’s and commanders like Andrew Cunningham’s—who understood that foresight, not firepower, would decide the wars of the future.

And so, beneath the still waters off Cape Matapan, where twisted steel now rests under layers of sand and coral, the echoes of that night endure—the thunder of Warspite’s guns, the blazing light of Valiant’s searchlights, the desperate cries of sailors on Zara’s deck, and the quiet hum of a decoding machine in an English country house that changed the course of history forever.

News

CH2 When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When America Outsmarted the Fortress Islands of the Pacific

When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When…

CH2 Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter And Flew Home And Shocked the World – Is It True Or Just A Myth

Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter…

CH2 The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed

The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed By 1944, Europe had…

CH2 The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While Other Allies Took Cover First

The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While…

CH2 ‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a Death Trap

‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a…

CH2 THE FORK-TAILED THUNDER: The Untold Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the P-38 Lightning — America’s Most Misunderstood Fighter of World War II

THE FORK-TAILED THUNDER: The Untold Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the P-38 Lightning — America’s Most Misunderstood Fighter of World…

End of content

No more pages to load