I was still numb when I pushed open the door to Cheryl’s office. The call had come that morning—the kind of call you can never prepare for. My dad was gone. Heart failure. No warning, no time to say goodbye. Just silence where his voice used to be. I stood there with the weight of that truth pressing down on me, already knowing that asking Cheryl for time off would feel less like a request and more like begging for air from someone who didn’t care if you drowned.

She was there as always, hunched behind her massive desk, fingers hammering her keyboard like she was trying to break it. I cleared my throat. “I need some time. Four days. My dad passed this morning. The funeral’s in Indiana.”

Her eyes didn’t leave the screen. “You can have two,” she said, voice flat, clipped. Like she was handing me a favor instead of taking away my last chance to bury my father properly. I blinked, thinking I must’ve misheard. “It’s a nine-hour drive each way,” I reminded her. That finally made her look at me, and the lack of anything in her face was worse than open cruelty. “Then attend virtually.”

My chest tightened. “Virtually? This is my dad. He raised me alone since I was ten. I’m not watching his funeral on Zoom.”

Cheryl leaned back, sighing like I’d asked her to donate a kidney. “Then you’ll have to choose. We’re in the middle of the Norland migration. Everyone’s expected to be here.”

Her words hit harder than I thought possible. Three years I’d given this place. Three years of building their systems, fixing other people’s mistakes, staying late, coming in sick, carrying weight that wasn’t mine. “Seriously?” My voice cracked, caught between grief and disbelief. “I’ve never asked for anything. Not once.”

She shrugged, like it was nothing. “This is business. We all make sacrifices.”

I looked down at my hands, and they were trembling—not from grief, but from rage that sat low and heavy in my chest. “Fine,” I muttered. “Two days.”

She turned back to her monitor like I had vanished from existence. I left without another word, but my head was ringing, buzzing with every late night, every moment I gave to people who wouldn’t give me four days to say goodbye to the only parent I had left.

Halfway down the hallway, past those dull cubicles where I’d spent over a thousand days, something inside me snapped—not with noise, but with finality. I looked back, just once, and the place I had given so much to looked different. The fake smiles. The lifeless stares. The motivational posters curling at the edges. It wasn’t an office—it was a coffin I’d been climbing into every morning.

I didn’t stop at my desk. I walked out. Straight through the doors. Straight into the night.

In my car, under the flickering lights of the lot, I sat for a long time, letting the anger simmer until it was calm, sharp, and clear. I still had a choice. Or maybe I didn’t—not really. Because deep down, I already knew what I was going to do.

When I finally made it home, the apartment was still, almost too still. I dropped my bag, kicked off my shoes, and stood in the dark as the silence wrapped itself around me. The stove clock glowed 11:47 p.m. I didn’t turn on the lights. I didn’t move much at all. Just walked to my room, stretched out flat on my back, and stared at the ceiling.

Dad was gone. And not one person from that office—those people I had sacrificed for—would be there when we laid him to rest. And that was the moment I decided.

Continue in the c0mment

I was still in shock when I walked into Cheryl’s office. The hospital had called that morning. My dad was gone. Heart failure, no warning, just gone. I stepped through the doorway, already knowing I was going to have to ask for something she wouldn’t want to give. Cheryl sat behind her oversized desk like always, typing like her keyboard owed her money.

“Hey,” I said, clearing my throat. “I need a few days off. My dad passed this morning. The funeral’s in Indiana, so I’d need 4 days. She didn’t look at me, just kept typing. You can have two, she said flatly. I blinked. It’s a 9-hour drive each way. She finally glanced up. Not a hint of sympathy. You can attend virtually. I stared at her, not sure I heard that right. This is my dad.

He raised me by himself since I was 10. I’m not watching it on Zoom. Cheryl leaned back in her chair and sighed like I was inconveniencing her. Then you’ll have to choose. We’re in the middle of the Norland migration. Everyone’s expected to be here. That hit harder than I thought it would. I’d given 3 years to this place.

Built every process they ran on. Worked late. Came in sick. Covered for other people’s screw-ups. Seriously? I said, voice tightening. I’ve never taken a sick day. Never asked for anything. She just shrugged. “This is business. We all make sacrifices.” I looked down at my hands. They were shaking. Not from sadness, from rage. “Fine,” I said quietly. “2 days.

” She turned back to her monitor like I was already gone. I walked out of her office without another word, but my head was buzzing. My chest felt tight. I made it halfway down the hallway toward my desk, past the same gray cubicles I’d sat in for over a thousand days. And that’s when something in me cracked.

Not loud, not dramatic, just final. Quick note before we start. How’s your day going? And where are you joining from? I didn’t mean to look back, but I did. I turned and stared down that hallway like I was seeing it for the first time. The fake smiles, the half dead eyes, the posters about teamwork peeling off the walls.

I kept walking, but not back to my desk. straight out the door. I sat in my car for a while before going inside. The parking lot lights buzzed overhead like they were trying to remind me I still had a choice, but I didn’t. Not really. I already knew what I was going to do. Inside my apartment, everything was still.

I dropped my bag, kicked off my shoes, and just stood there in the dark. The clock on the stove read 11:47 p.m. I didn’t even sit down right away. I just walked to my room, laid flat on my back, and stared at the ceiling like it could tell me what the hell just happened. Dad was gone, and not one person from that office would be there when we put him in the ground.

At 2:30 in the morning, I got up and opened my laptop, logged in remotely. I’d done it a 100 times before, during holidays, weekends, nights when other people were too lazy to fix their own mess. But this time was different. I went straight to my folders, not the company junk. I didn’t touch client data or project files that weren’t mine.

I had my own stash, stuff I’d built from scratch just to keep the machine running when no one else gave a damn. Integration manuals, client specific troubleshooting sheets, API call structures I documented myself because no one else knew how they worked. Notes from failed attempts, fixed versions, cleaned up code snippets, config backups.

Most of it I built on my own time. the rest while covering gaps no one else bothered to fill. And now I was taking it back. While I was working, I remembered Cheryl telling me I had to choose. Yeah, I chose. I started zipping files, encrypting folders, running check some scripts. My fingers moved on muscle memory, but my head was somewhere else.

I thought about dad standing in the garage showing me how to use a power drill the right way. If you’re going to build something, he’d say, build it like it’s got to outlive you. That’s what I’d done at work, and none of them gave a By 6:00 a.m., I’d scrubbed every last version off the shared drives. Gone.

Wiped from the system, replaced with a single text file. Documentation removed by original author. No backup available. Then I opened a new email. Subject line. Formal resignation. Effective immediately. No long speech. No thanks for the opportunity. Just two short paragraphs. I attached my resignation letter, hit send, shut the laptop, and pack my bag.

I didn’t even look at my phone. It started buzzing around 6:30, probably the morning crew noticing the missing files. I turned it off. At 8:10, I was at the airport, standing in line, hoodie up, backpack slung over one shoulder, ticket to Indianapolis in my pocket. The gate agent barely looked at me.

I didn’t care. For the first time in three years, I felt like I wasn’t pretending. While boarding, someone behind me in line was complaining about their seat assignment. I wanted to turn around and say, “At least your dad’s still breathing, but I didn’t. I just kept walking. Middle seat, tight row, no leg room.

Didn’t matter. I was going home.” I stared out the window as we took off, not thinking about the job or Cheryl or Hal or any of them. My mind was on the chapel in Bloomington. The coffee can my dad kept bolts in. The smell of wood stain. The way he used to whistle while he worked. Like the world was a little less broken if you just stayed busy enough.

I had no clue what was waiting for me out there. But I wasn’t scared. We touched down just after 2 p.m. The second the wheels hit the runway, I turned my phone back on. It lit up like a damn Christmas tree. 19 missed calls, mostly from Hal and Cheryl. Voicemails started rolling in before the lock screen even loaded.

I played the first one. Hey, it’s Hal. Uh, we noticed some files are missing. Could you give me a call when you land? Second one. Cheryl clipped tone. We’re escalating this internally. If this was accidental, please clarify immediately. Third one, pure gold. How again? This isn’t how professionals handle things.

I snorted and slid the phone back into my pocket. That was rich coming from a guy who once forgot to tell a client their contract autorenewed for double the rate. I picked up my rental, a dusty blue Ford Focus that smelled like fast food and sadness, and drove south toward Bloomington.

The farther I got from the city, the easier it was to breathe. Dad’s house was just how I remembered it. Low brick, sloping roof, porch light that flickered when the wind hit right. I stepped inside and got hit with the smell of sawdust, old books, and black coffee. Like time hadn’t touched it. His boots were still by the door.

A mug sat on the kitchen counter half full like he just stepped outside for a second. I just stood there, hand on the doorframe, breathing it all in. That night, I stayed up in the garage, sat at the workbench while the heater hummed in the corner. I started digging through old drawers, clamps, chisels, tiny screwdrivers.

In the bottom cabinet, I found a metal tin packed with baseball cards, rubber banded in groups, just like he used to keep them. He never collected for money. Said stats told better stories than faces ever could. My phone vibrated again. I didn’t even have to look. Emails now. First one from Cheryl. Subject line. Urgent documentation access required client disruption.

Second one followup needed migration incomplete. The third came from Hal hours later. Can we schedule a quick call tomorrow? Want to discuss your situation and your father’s funeral plans. Funny how fast they learned his name. I clicked reply. Typed tomorrow at 2 p.m. Eastern Standard Time works. I’ll send the invite. No sign off.

No emotion, just business. I set it for exactly 2:00 p.m., right in the heart of their Norland migration deadline. I knew what that hour meant to them. I closed my laptop and looked around. The whole garage was quiet, except for the soft hum of that heater and the occasional creek from the old rafters.

It felt more alive than any office I’d ever worked in. I leaned back in dad’s old chair, kick my feet up on the workbench, and watched my phone buzz again. They were panicking. good. Now they could feel what it’s like to lose the one person holding everything together. The next morning, I brewed a pot of coffee and dad’s chipped Mr.

Fixit mug and set my laptop on the kitchen table. Same table I’d eat and toast at before school. Same view of the backyard where dad taught me to mow in straight lines. At exactly 1:59 p.m., I clicked the meeting link. Hal’s face popped up first, redeyed, collar crooked like he hadn’t slept. Cheryl joined next, hair pinned up tight like always, mouth already tense.

Then came a third window, some lady in glasses with legal written all over her face. First, Hal said, voice slow and practiced. We’re very sorry about your father. I didn’t respond. He waited, then glanced at Cheryl. She jumped in. We need access to your documentation. The migration is falling apart without it. I tilted my head.

My documentation? You built it on company time. The legal woman chimed in. It’s considered work product. I laughed once, short and cold. You mean the scripts I made after hours? The guides I built because no one approved a training budget? The notes I wrote just so I wouldn’t get blamed when Hal forgot a meeting doesn’t change the fact that it’s proprietary.

Legal said, “No, I said it’s not. It doesn’t contain any client data, source code, or internal IP. It’s tools. My tools built because I was left to sink or swim, and I chose not to drown. Cheryl leaned forward. Norland’s team can’t complete the migration. Reporting functions are dead. Clients are asking where their dashboards are. I sip my coffee.

Sounds like a staffing issue. Hal rubbed his forehead. Look, I understand you’re grieving, but we really need a solution here. I nodded. I have one. I’m not rejoining the team. I’m not reinstating anything, but I’ll consult Cheryl’s eyes narrowed. Excuse me? 300 an hour, 20our minimum, paid upfront.

I’ll walk your people through what they need, answer questions, and help you hit the finish line. That’s extortion, Cheryl snapped. I shrugged. It’s supply and demand. Hal spoke up. We can’t approve that kind of spend without going through finance. Then talk to finance, I said. because the clock’s ticking and Norland’s not going to sit around while you fumble through backups that don’t exist.

Legal stayed quiet typing. Also, I added, I won’t be working around your schedule. I’m handling my father’s estate this week. Calls are limited to 2 hours per day. You’ll get the window I give you. Silence. Cheryl looked ready to snap, but Hal was already nodding. Can you send over a formal agreement? He asked. I’ll send terms.

Once I see the funds, we’ll schedule the first call. Howal nodded again like this was hurting him physically. We’ll expedite it. Legal spoke for the first time since typing. Please don’t delete any additional company related material. There’s nothing left to delete. I said you’re already standing in the crater. I ended the call, felt no guilt, no second guessing, just calm.

The kind of calm you get when you stop explaining yourself to people who never cared. Thursday morning came hard. I pulled on a wrinkled black button-up, still faintly smelling like dad’s garage. I didn’t bother ironing it. He wouldn’t have. The chapel was the same one we buried mom in. Same stained glass, same creaky pews, same carpet that always felt just slightly damp, no matter the weather. Now it was dad’s turn.

I stood near the front, hands shoved in my pockets while people filtered in. old neighbors, his buddies from the community college, a couple guys from the VFW. They weren’t dressed fancy, but every one of them showed up. “Your dad helped me fix my water heater during a snowstorm,” one man said, clapping my shoulder.

“Wouldn’t let me pay him,” another added. “Even his barber came, holding a little box of sugar cookies.” “He hated getting haircuts,” she laughed. “But he always brought me pie in July.” I didn’t speak much, just nodded, hugged a few folks, took it all in. Then I saw Mister Banner, my high school shop teacher, coming down the aisle.

Same thick glasses, same stiff walk. He pulled me into a hug like I was still 17. “Your dad never stopped bragging about you,” he said, voice thick. “Every time I saw him, it was my kid built that whole damn system by himself. You were his whole world.” My throat clenched. I just nodded. Couldn’t get a word out. The service was simple. Few prayers. A hymn dad liked.

Some guy from the college gave a short eulogy about how dad always fixed the vending machines when facilities wouldn’t. It wasn’t flowery. It wasn’t long, but it was real. Afterward, I stepped outside, pulled out my phone, and saw the number. 27 missed calls. I slid it back into my pocket without even reading the names.

I walked around back to the shed. On the bench sat a small wooden pendant. Still rough on the edges, half sanded, loophole not drilled yet. There in the center was a small wooden pendant. Still rough on the edges, half sanded, loophole not drilled yet. I picked it up, turned it over in my hand. He’d been making it for me.

I remembered him showing me the design a month ago. Said it was walnut from a tree he’d cut down in Aunt June’s yard. I grabbed some sandpaper and got to work. Not fast, not careful, just steady. I didn’t feel proud or smug or justified. I just felt clear. Friday morning, I was back at dad’s kitchen table.

Coffee in one hand, laptop open, earbuds in. The Norland call started at 9:00 sharp. Their whole team was there, plus Hal, Cheryl, and some guy I didn’t recognize, who looked like he hadn’t seen sleep in 3 days. Howal cleared his throat. We had to delay the presentation. Norland wasn’t happy. I sip my coffee. That sounds like a problem. Cheryl jumped in.

We need to get this fixed now. They’re threatening to pull out. I nodded. Then let’s get started. I shared my screen and walked them through everything line by line, error by error. Broken API links, failed queries, dead-end report scripts they tried to patch with copypaste fixes. One process had been misconfigured for three months. I flagged it in January.

No one touched it. Hal tried to move things along. Can we skip the background and just No. I cut in. You’re paying for clarity. You’ll get clarity, not shortcuts. He shut up. I kept going, answering their questions one by one. I didn’t sugarcoat it. Didn’t soften the tone. This part broke because someone deleted the fallback logic.

This report fails because the database connection times out every third run. I told you that in December, this is what happens when you rely on duct tape and in turns. By the halfway point, no one argued. They just nodded, typing furiously, looking like people trying to rebuild a plane midair. An hour and 47 minutes later, I closed the session.

Howal leaned in. We appreciate your help. That was necessary, Cheryl added. We’ll need you back on Monday to finalize the rest. I shook my head. Not in our contract. But we still have questions. She said, “Norland, then put them in writing.” “Wait,” Hal said. “Are you saying you’re not available Monday? I’ll be at my dad’s lawyer’s office Monday morning.

Priorities.” They both looked stunned, like they forgot this was all happening because they couldn’t spare me four damn days in the first place. Cheryl tried to salvage it. Well, just let us know when you’re available. I clicked leave meeting. That was the beauty of being prepaid.

I didn’t know them a single second more. Tuesday afternoon, I logged into what was supposed to be the final call. No greetings, no small talk. Just their faces staring back at me like they just walked out of a car crash. Howal looked wrecked, hair uncomed, tie loosened, voice low. The demo went badly. Norland’s pissed Cheryl didn’t even try to hide it.

They’re giving us two more weeks to fix it. After that, they’re walking. I nodded once. Understood. We went through the last batch of questions, script adjustments, data sync issues, a report that somehow kept pulling March figures for every month. I kept my tone level, calm, clear, professional. They asked, I answered, nothing more.

At the end, Hal glanced off screen, then back at me. Before we wrap, there’s one more thing. Here it comes. He cleared his throat. We’ve been talking internally, and we’d like to make you an offer. A real one, Cheryl jumped in before I could respond. Director level remote. You’d oversee your own team.

We’d hire three under you to start. You’d report directly to Hal. And she hesitated. 50% raise. Also, Hal added, “You’d be on the executive planning calls going forward.” Full seat at the table. The line went quiet. I could hear my own heartbeat. Not because I was nervous, just pissed it took this long. I looked at them both.

Their faces said it all. This wasn’t gratitude. This was desperation. I leaned back in the chair. “You’re not offering that because I earned it. You’re offering it because you’re scared.” Hal tried to protest. That’s not I held up a hand. Don’t. You had 3 years. I was useful to you the entire time, but you never once treated me like I was valued until things blew up. Cheryl looked down, silent.

I buried my father last week, I said. And your first reaction was to demand access to my work, not ask if I was okay. Now you want to promote me? Hal exhaled slowly. We’re trying to do right by you now. I gave a half smile. Too late. Is there any version of this offer you’d consider? He asked. No, I said. Because it’s not about the title or the money.

It’s about the fact that I had to take everything away from you just to get noticed. Cheryl whispered. We didn’t realize. You didn’t care to realize. I cut in. And that’s the difference. Another long silence. I let it hang. Then I clicked leave meeting. Clean. Final. Dad used to say people only show their cards when they feel the pressure.

Turns out he was right. Two weeks later, I got an email from Cameron in finance. Subject line re update on Norland. I clicked it without much thought. Norland pulled out. Three other clients are re-evaluating. Just thought you’d want to know. No. Hello. No signature. Just that. I stared at the screen for a second. Didn’t feel smug.

didn’t feel sorry either, just right. They’d gambled on pretending I was replaceable. And now the bill had come due. A month later, I joined a smaller firm out in Columbus. 10 people total. No layers of On the second call, the CEO asked, “How are you holding up after losing your dad?” Not, “What can you do for us? Not how fast can you start.” Just that.

I took my time on boarding. They told me, “Family first. Work comes second or it’ll ruin both.” It felt like breathing fresh air after years of sucking dust. 6 months passed. I was settled in, finally sleeping full nights. Garage cleaned. Dad’s shop reorganized. That’s when I saw it. A message on LinkedIn from Hal.

I know I handled things wrong. I’m trying to change. You were right about all of it. Your dad sounded like a remarkable man. I stared at it for a while, not because I didn’t know what to say, just deciding if it was worth it. I finally typed back, “He was remarkable. Thanks for recognizing it.” That was it.

No grudges, no second round, just closure. That night, I set the wooden pendant on my desk. Walnut smooth now. I’d finished sanding it two months ago, just like he would have done. Not perfect, but solid like him. Sometimes the strongest move isn’t burning the place down. It’s walking away with everything they didn’t realize they needed and letting them sit in the silence you left behind.

News

“They said love would conquer everything, but even love has limits” – Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s marriage COLLAPSES after a private confrontation where Keith allegedly called her out, leaving the actress shaken and friends stunned by the truth they never expected to surface

“They said love would conquer everything, but even love has limits” – Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban’s marriage COLLAPSES after…

A newborn was left to die in the snow – But A cowboy with no family found her.CH2

A newborn left to die in the snow. A cowboy with no family finds her. What begins as mercy turns…

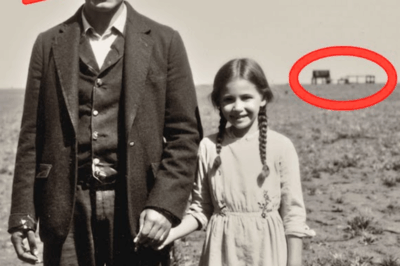

In The Photo: A Father Leads His Daughter On A Trail In 1909 — But Hunger Already Marked That Look…CH2

Have you ever wondered what it feels like to look into a photograph and realize it hides a tragedy no…

When June’s father discovered she was pregnant, he didn’t ask who the father was. He just dragged her into the wilderness and gave her away like livestock.CH2

When June’s father discovered she was pregnant, he didn’t ask who the father was. He just dragged her into the…

I RETURNED FROM MY TOUR TO FIND MY 9-YEAR-OLD SON ON THE FLOOR. HIS CUSTOM WHEELCHAIR WAS…CH2

The first thing I saw when I stepped through the door wasn’t my wife. It was my boy—nine years old,…

“Your daughter is still alive” – Homeless black boy ran to the coffin and revealed a secret that shocked the billionaire…CH2

“Your daughter is still alive” – Homeless black boy ran to the coffin and revealed a secret that shocked the…

End of content

No more pages to load