Part I

The night the semi came barreling down the hill into the high, dark shoulder of the cul-de-sac, everything smelled like ozone, hot rubber, and the bitter edge of endings.

I’d known this corner since I was six—since before I knew that Charles and Margaret Barrett weren’t my parents by blood, and that the girl they’d loved, a poised ballerina with porcelain ankles and swan-neck grace, wasn’t their daughter either. That story had reached me in middle school with all the tactlessness of a bus-stop rumor. When the DNA re-test came—the kind of thing usually kept quiet, but in our town even secrets wore neon—the Barretts drove out to the county Home and found me. They brought me back. They gave me a room, a wardrobe, a last name, and a list of ways I did things wrong.

I learned to move small. I learned to tuck my elbows in so they wouldn’t thump doorframes, to smile with my lips closed so my teeth didn’t look like a dare. The girl in the house—Vivian—whose fingers bled prettily in satin shoes, had more authority over my life in a glance than I had in a poem. Their son—Ethan—was the family’s northern star. Captain of the tennis team, first chair violin, honor-society golden boy. He had cheekbones that could cut twine, and he liked things that stayed in their assigned places.

The first time I died, it was for him.

In that life, I saw the headlights veer and I stepped in front of Ethan, and then there was a crack like the sky snapping in half, and my legs turned into wet paper. Ethan survived. Vivian cried on the asphalt, mascara pattering black raindrops on her cheeks. The Barretts told me I was ungrateful for interfering. They left me in a patch of county woods—because rich people have imaginations that are worse than movies—and when the wild dogs padded out with eyes like marbles, I went as quietly as I could. I thought I was supposed to. I thought maybe I owed them a dignified exit.

And then—impossible—there came the second chance. Same curb. Same air. Same electrical storm crackling at the edges. Same panic in Vivian’s throat, a pinched squeal as she bolted into the road. Same thunder in Ethan’s voice: “Why stop me from saving her?” he roared, grabbing my wrist so hard I felt my bones ring like tuning forks. It was a line perfect in its self-mythology: he as hero, me as obstruction, her as prize. I could smell the iron in his adrenaline. He surged forward.

But not this time, I thought.

Reborn, I stepped aside.

I watched the semi—not a “lorry,” as the old storybooks would have it, but a long-nosed American semi with a chrome grin and dead-eyed running lights—thunder past the stop sign. It weighed more than ten tons; it had all the momentum of bad decisions with mechanical advantage. Ethan sprinted into its wake as if he could body-check inevitability. He reached Vivian’s shoulders. He shoved her toward safety, twisted to keep her from the brunt, and in that partial triumph—the way a seasoned player returns a wicked serve—the semi’s grill kissed his arms and took them.

There are screams you don’t forget. I didn’t forget the wild dogs. I didn’t forget my own. I won’t forget Ethan’s, a sound torn out of him like scaffolding pulled from a building under construction. The driver—mid-50s, pallid, his jaw working like he had citrus rind in his teeth—swore and braked and started shouting about blind corners. The Barretts’ floodlights popped on. Vivian fell to her knees, her streaming ponytail slapping her cheeks like a wet flag. The Barretts came running.

I had a choice, right then. Old me—good me, orphan-me who memorized the Home’s rules and learned to point her toes in borrowed slippers—would have given up her body to the triage. New me slid into a role I learned from the Barretts: triage of reputation.

“Ethan!” I cried, a pitch-perfect sister’s panic. “Hang on, okay? I called nine-one-one. The paramedics are two minutes away.”

He blinked up at me, white as smoke. His breathing came in ragged freight bursts; I could almost see the ghosts of both his arms, fingers flexing to a music they’d never play again. His eyes, prickling with hot male fury and awful tenderness, searched for Vivian. She scooted—on all fours—toward him, but I caught her shoulder and pushed hard. It didn’t take much; she was all delicate muscle and stagecraft.

“You ran into the road,” I said, my voice cracking in a way I made sure everyone would hear. “I get it, Viv. You’re mad at me for being back. You’re tired of sharing. Fine, hit me, scream at me, tell your friends I’m a charity case. But don’t you ever sprint into traffic again. Look what you did to Ethan.”

It is a thing to watch a family recalibrate, to see a constellation flicker and redraw itself as though an unseen astronomer moved a star with his thumb.

Vivian fell back on the gravel. Her tights snagged; her shins glistened red. In the Barrett house, her ankles were sacred, wrapped, elevated, iced at the first whisper of strain. Tonight, nobody glanced down. Margaret crumpled to Ethan with a sob so raw it felt like someone tearing bedsheets. Charles stooped into a silence that was both flinty and fluttering, his jaw a locked hinge. The paramedics arrived, professional and calm, and I heard the words “bilateral traumatic amputation” and “orthopedic consult” and “no salvageable tissue.”

When they lifted Ethan into the ambulance and his sleeves lay flat as flags at half-mast, the world froze for a long stuttered heartbeat. Vivian reached toward the open doors. “Mom? Dad?” she called, small as a music box melody.

Margaret looked through her.

The doors clapped shut. The night swallowed the siren. Vivian stood in the blue strobe wash, hands open, posture collapsing in on itself. When she finally turned, I saw how young she was—how young I had been—when an audience decided the value of your body.

I took the Barretts coffee and pretended it was the most generous thing I’d done in years. Charles’s eyes caught mine with a flinty respect that belonged to a subordinate who drafted clean memos. “Thank you, Jenna,” he said. The way he said my name sounded like we were halfway to a truce we’d never actually declare.

The words I’d heard in another life—viper, ungrateful, not our daughter—did not appear that night. They would come later, in a different shape, under different lighting. Hatred rarely repeats itself verbatim; it loves new costumes.

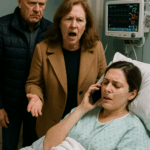

At the hospital, a surgeon with hands like quiet birds told us there was nothing to be done for Ethan’s arms. Margaret fainted for the second time. Somebody poured water. Someone else adjusted a thermostat that didn’t need adjusting. Vivian hovered in the doorway, her ankle turning a shade of disappointment. I offered granola bars I had no intention of eating. I ferried tissues. I played the part of the girl who had learned the Barretts’ grammar and could recite it back to them.

Before dawn, Margaret turned those damp, unfocused eyes on me. “You should—eat,” she said, as if discovering new verbs. Charles only nodded. The wi-fi password blinked on a whiteboard. The fluorescent lights hummed the pitch that made teeth hurt.

I smiled in the milky, exhausted way that the kind caregiving girls do, and did not look at Vivian in the doorway when she whispered, “Dad? Mom?”

They didn’t hear her. Or they chose not to. That’s the thing about this family: they’d call it triage. I call it premeditation.

The second life had begun with an ending. I felt nothing like sorry.

I felt present.

And presence, I’d learned, was a kind of blade.

Three weeks later, when the hospital discharged Ethan into a home with new railings and rounded doorways and a bench added to the shower, I brought my textbooks home with me and studied in the lamplight. The A-levels—though here in Carolina, people just said senior year exams—loomed. Vivian tip-toed through the house with restaurant shifts and rehearsal fatigue. Margaret whispered about caregivers in a voice that carried the brittle iridescence of pearl earrings. Charles paced through conversations about contingencies.

In the early evenings, I visited Ethan’s room. I learned the choreography of small kindnesses. I positioned a glass at the corner of his lips and tilted just enough. I used a washcloth to clean red wine off his scalp after a boy named Ryan at a party poured it over his head to prove a point about cruelty. I said “I’m sorry” in a voice that made it sound like I meant the world, and in my head I noted who stayed, who watched, who sneered, who stood aside.

This time I did not save Ethan.

This time I saved my memory of myself.

And I kept a ledger that would become a plan.

Part II

The Barrett home sat on a bluff above a double-laned road, a white-brick Georgian with black shutters and an American flag that had seen more weather than wars. It was a house that believed in discipline: library ladders, index cards in the pantry for inventory, a mudroom where shoes lined up like obedient soldiers waiting for inspection. It had a music room for Ethan and a mirrored studio for Vivian. My room had a small window that faced the oak, and a closet rod half-empty, as if the house hadn’t decided yet whether I was staying.

In a country that swore its love for second chances, there’s a quiet cruelty for those returning from the margins: you’re supposed to be grateful, charming, tidy, and never, ever noisy. I was reborn into that assignment the way a recruit is issued a uniform. But this time, I wore it like a costume.

Ethan came home with his gauze-wrapped stumps tucked into soft, oversized hoodies. In the mirror over the mantel, his posture made him look like a boy with an illness that mispronounced his name. He wouldn’t let a soul help him unless that soul was hired. The caregiver—a woman named Ms. Lockwood, with forearms you’d trust with a newborn or a chainsaw—learned his rhythms. She did not look away when he spilled down his jeans trying to make it to the bathroom alone. Vivian did. That moment—a flinch, barely there, the backward tilt of a pretty girl’s chin—registered inside Ethan like a hot nail hammered into wood. He said nothing, which is how hatred starts in certain families. It doesn’t arrive loud; it collects interest quietly and compounds.

The first week, it was just logistics: ramps like tongues on the front stoop, an occupational therapist who taught Ethan to nod his head to turn pages on a tablet, a social worker rattling off numbers and terms like “SSI” and “short-term disability.” Margaret cried in rooms I wasn’t in and smiled in rooms I was. Charles said “We’ll figure it out” with a businessman’s certainty that there’s always already a plan on a whiteboard somewhere if you look hard enough.

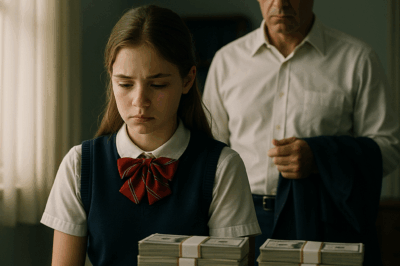

I offered Margaret tea and Charles strong coffee at exactly the right moments—just before the tremor in their hands revealed itself. I placed myself in the camera’s frame, in the kind of invisible way that reads as dependable. When Charles took calls from the office, I listened. Not obviously. Just enough. The company—Barrett & Co., a blend of logistics and regional warehousing—had a sliver of national footprint and a local reputation like an oak: old, generous shade, and roots you didn’t disturb.

“Board wants a succession plan,” Charles muttered one night, not to me. He said it to the room, to the HVAC murmur, to that portrait over the fireplace where his own father stared down like a saint of quarterly earnings. Ethan was the named heir. Ethan without arms was still the named heir on paper. Paper had a way of pretending nothing had happened if it made the numbers less complicated.

I grocery-shopped, line-edited margins in my notebooks, and waited.

At dinner the following week, Vivian tried to bring back the old set. “Ethan, you should come to the graduation ceremony tomorrow. You’ll feel better,” she chirped, all treble and optimism, which plays well on middle-school stages and poorly in rooms lit by the ache of recovery.

Ethan looked at his plate like it had wronged him. “No,” he said. Then, seeing Margaret’s eyes begin their watery tremble, he amended: “Fine. I’ll come.”

I watched the conversation drift to meteorology and mocktails, the way families turn the volume down on hard news and turn it up on weather. Under the table, I rested my heel on the floor and took a breath that tasted like varnish and old leather.

There’s a strange joy in a plan that writes itself with the logic of an avalanche. You nudge this snow. That one falls by habit. Gravity handles the rest.

At graduation the next night, the auditorium lights made everyone look a little jaundiced and a little seventeen. Vivian danced a modern piece that turned the air into ribbons; when she finished, the applause fell like confetti. Ethan clapped his thighs together in a rhythm no one else could hear. Then the principal announced the duet: “Please welcome our juniors, Lena Foster and Ryan Scott.” Vivian’s gaze flicked to Ethan. She knew. He had loved Lena since spring of freshman year and hated Ryan for two of those years with an intensity that improved his tennis serve.

Ethan’s face closed like a fist. Lena and Ryan moved well together; they’d been moving well together for months. The rumor mill had made rings around it. When the last note trembled out, Ethan asked Ms. Lockwood to take him home. Vivian stopped him, planting herself between his wheelchair and the aisle. “Edward—” she began, and caught herself. “Ethan, just stay a little longer. There’s a mixer. You can talk to her. Ask. Don’t let rumors eat you alive.”

The mixer smelled like Sprite and cologne. Ethan rolled toward Lena and tried to stand on a tide of willpower that had no physics beneath it. Ryan blocked him with a smile too white to be honest. The first splash of wine hit Ethan’s hair like a punchline. The second made the onlookers laugh the way teenagers laugh when they don’t know the cost of a thing.

“Apologize to my brother,” I said behind a phone held high, my thumb riding the braided edge of the emergency-dial button. “Or I press this and campus cops will get a recording of you committing an assault. A-levels start in eight days. Enjoy county lockup.”

“Who do you think you are?” Ryan spat.

“Someone who knows the handbook,” I replied, and kept my face bored because the law loves bored witnesses.

He muttered a sorry designed to be escaped from. They left. The crowd dissolved. Vivian arrived two minutes too late with the flustered breath of someone who’d ducked out for a rumor that didn’t pan out and had returned to a war movie.

Ethan told her to get out in a voice so flat it could have been concrete.

Back home, Ethan locked himself in his room and punted the baseboard so hard we found a half-moon shoe scuff the next morning. The maid put out a bowl of tomato soup on a tray. There is a kind of boyhood that believes a mother’s soup is a sovereign cure. Ethan kicked it over and the red spread across the floor like a fairy-tale map of blood.

Charles shouted, with the impotent rage of men who know how to fix broken spreadsheets but not broken sons. Margaret knocked in a rhythm that had soothed him when he was three. Vivian stood in the hall with her fingers crushing themselves in her palms and whispered, “I’m sorry,” like a habit. The word landed like a moth on the wrong lampshade. It fluttered a little, then died.

For a week, the staff rotated, and Ethan burned through eighteen caregivers. The nineteenth—Ms. Lockwood—came back with a jaw like a lifeguard’s and refused to flinch. He accepted her the way men like him accept facts they can’t change: he grimaced, then he got used to it.

But the house changed. Gravity changed. Viv’s laughter—once something you could set a clock by, bubbling in at 4 p.m. after rehearsal—stopped. She moved like a person waiting for the strike. The maids were meaner to her. Not openly. Just that little extra roughness with folded laundry, that little delay in answering her call for water. That’s how cruelty travels in households: downhill, from master to staff to the calf at the bottom.

When Ethan beat Vivian the first time, it happened behind a closed door. Margaret found her later, eyes glassy, lip split, saying she’d tripped over a duffel bag. Charles found a broken tennis racket out back where the practice wall used to be. The strings splayed like snapped violin bow hairs. He didn’t pick it up. He stared at it until his jaw set, then he went inside and poured himself bourbon he wasn’t supposed to be drinking on a Tuesday. I watched him through the doorway’s crooked rectangle and decided that men like Charles believe their love for a son and their love for a company are the same category of fidelity.

They are not.

I learned the company’s books by osmosis. I learned that over-leveraged warehouses groan at the seams. I learned that drivers hate routes designed by people who never drove. I learned that a well-timed email with the right ratio of empathy to iron makes men twice my age call me “kiddo” with affection rather than condescension. I learned that the board meets on Wednesdays and that the conference room where they meet has a weird acoustic flutter that makes angry voices sound like doves. I learned—and this mattered most—that Charles had begun to admire me.

“You think clearly,” he said one night, after I gave him a two-sentence solution to a six-page problem. “You’re my daughter.”

He had never said it that way. He had said it like a social form, not like a blood oath. He said it that night like it mattered beyond the tax benefits.

I smiled and said something appropriately demure and did not tell him that the word “daughter” fits me like a coat I stole, altered, and now wore better than the original owner.

I did not tell him I would not save Ethan.

I would save the ledger.

Because one day I would collect.

Part III

It’s moral algebra, what happened next, and people who’ve never had to solve for survival will call it cruelty and say it slow so they can hear themselves being righteous. I call it repayment in a currency the Barretts understood.

After the graduation party broke Ethan’s pride in half, the house turned on an axis no one could see. There’s an old phrase—long illness, no dutiful children—that maps neatly onto wealth’s inverse: long humiliation, no loyal parents. At first, the Barretts tried the equations they knew. They hired a psychiatrist who collected payments from both the family and the county by coding Ethan’s treatment under three different billing trees. They secured an appointment schedule: SSRIs in the morning, atypical antipsychotics after lunch, a benzo to rock him to sleep. For a week, it worked. He quieted. He slept. He ate. And then at three in the morning, he launched himself out of his bedroom window and shattered the small bones in his foot like chalk.

At the hospital, under bleached lights, he raved about Vivian and revenge. The attending wrote “acute agitation” and “suicidal ideation” and used a marker that squeaked on the whiteboard. Margaret cried softly, like a metronome. Charles rubbed his temple like he was negotiating with a foreign minister who had a nuclear headache.

Three words floated down the hallway like a paper airplane: mental. health. facility.

Charles didn’t say them. Margaret didn’t either. I did, gently. “Long-term care could be good,” I murmured, and then I folded the moment up and put it away in a drawer for later.

Vivian, that week, floated through the house like a ghost allergic to light. If she heard Ethan bark her name, she fled. If she heard his door slam, she jumped. The staff had taken the temperature of the house the way staff do; the warmth radiated from me now, which meant the heat was hers for the taking, too, if she stood in my shadow. She didn’t. Pride is a dancer’s friend on stage and her bully at home. It had her in a chokehold.

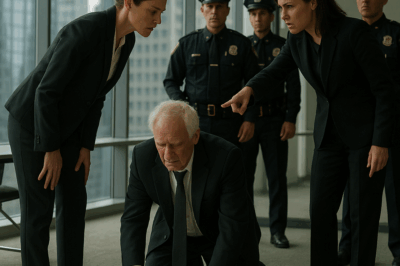

When the call came from the police station—Ethan popped for possession with intent, the kind of charge a DA loves for its clean upward mobility—I was the one who answered the phone. “We’ll be right there,” I said, as if my life hadn’t already raced near that corner a hundred times. Margaret and Charles posted bail at an hour that made decent people slur. We brought Ethan home smelling like sweat and denial. He took one look at me on the sofa next to Vivian and exploded toward her with the gracelessness of a man who forgets that legs are weapons even if arms are not.

“You ruined my life!” he shouted, the vowels slashed, the consonants knotted. He kicked her. Vivian is faster than she looks. She caught his shin between her calves, twisted, and took him down. She straddled him and punched like a girl who’d practiced on a bag secreted behind the studio mirrors. Tears and spit made a glitter on her face.

“I never asked you to save me!” she yelled, and the sentence ricocheted around the double-height living room like a bullet that never quite struck flesh.

Margaret slapped her and delivered the kind of maternal verdict that would read as biblical if it weren’t so petty. “Blood is thicker than water,” she hissed. “You can never raise someone else’s child.”

Vivian went very still. Then something in her—an axis, a fulcrum—tilted. “You kept me because I looked good in your Christmas cards,” she said in a low, steady voice that would have made the town’s holiest pew-renters cross themselves. “You despise honesty because it’s unphotogenic. You don’t get to throw me away and look righteous doing it. I’m not your charity. I’m not your scapegoat. I’m leaving.”

She grabbed a duffel and a windbreaker and a bag of toiletries and walked out. Charles lunged. Vivian turned with a flinty look that matched his. “Touch me,” she said, “and I go to the press. I tell them everything.” The everything didn’t exist, or not exactly, but the threat did. Wealth hates mess more than it hates crime. Charles let her go.

After the door closed, the house sighed, a long, old breath.

Margaret tried to draw me into her new orbit. “Honey,” she said, the word soft but the angle selfish. “You’re good to us. You’ve always been. Your studies. I worry for you.”

I rested my hand on her knuckles—the kind of gentleness that looks like love in photographs. “I’ll be fine.”

Charles began inviting me to the office. The first day, he introduced me to the CFO and three operations managers whose faces all looked like a weather map for different climates: one sunny, one perpetually overcast, one heavy with inland thunderstorms. He asked my opinion about warehouse slotting and driver retention. I had thoughts. I framed them with the respect that makes older men feel safe and the precision that makes them feel impressed. In two days I was a guest. In two weeks a fixture. In a month, Charles stopped saying, “We’ll see,” and started saying, “Let’s do that.”

At home, Ethan slid toward his private apocalypse. He destroyed his violin with his heel. He tore love letters in his teeth. He had the maid hold a Zippo to a pile of trophies and watched them warp and slump into a mythology’s spoils. “Burn it all,” he said. “Burn me.” She didn’t. But she learned his cadence. Rage, ruin, weep, sleep. Repeat.

The second time the police called, it wasn’t for drugs; it was because Ethan had tried to climb the fence at Vivian’s apartment complex. A security guard intercepted him, and Ethan told him that boys with no arms are still men, still sharp, still shivs, still something to fear. The guard did his job and called the cops. We pulled strings before a report got filed. Margaret begged me to take the lead; Charles authorized a lawyer in a suit that looked more expensive than sanity.

“Jenna,” Charles said that night, after we averted yet another public relations meteor. “I don’t know what we’d do without you.”

“Sleep less,” I said with a little smile, and he laughed the grateful laugh of a man who thinks gratitude can prevent what’s coming.

A week later, the boardroom became my stage. I presented a compact, data-bright plan that rebalanced routes, renegotiated insurance, and turned two money-losing depots into one profitable hub. Somewhere in the third slide, Charles stopped blinking. Somewhere in the fifth, the CFO’s pen stilled. Somewhere in the seventh, the senior independent director nodded once, the nod of an old man who had made more enemies than I could count and knew a fellow player when he saw one.

They voted to institute the plan as a “pilot.” We all knew what that meant: when the numbers bloomed, so would my title. Charles didn’t say it out loud that day; pride makes men slow to gratitude when gratitude has to share a table with concession.

The night the first report came in—a green line lifting where a red one had dipped for months—Charles poured me bourbon he didn’t pour for his son. “You’re a Barrett,” he said again, like he was casting a spell and trying to persuade an indifferent god.

I let the moment sit in my palm like a coin I could spend later.

Upstairs, Ethan had an episode. He bit himself. He hit his forehead against the wall hard enough to leave a pale, obscene kiss of plaster on his skin. The staff restrained him, the doctor sedated him, the psychiatrist adjusted dosages. For a week, again, it looked like we might plateau. At 3 a.m. three days later, Ethan jumped from the second-floor landing and bashed his head on the tile. The ER staff stitched him back together. He woke uncured and furious.

“I’m killing her,” he insisted, spitting out the words like laughing gas gone moldy. “Vivian took my arms. I’ll take her life.” The restraint straps creaked. Margaret’s cheeks were gray. Charles’s mouth was a straight ruler.

They broke that night in a quiet, affluent way. “We can’t,” Margaret whispered. “I can’t.”

“We send him away,” Charles said, the “we” doing a lot of the work and none of the penance. He didn’t look at me. He knew I’d agree. He knew I already had a brochure in my inbox.

I sent it.

And then, as if the gods were embarrassed by how easy it had gotten, Ethan called me himself. “Sister,” he said, and the word snaked over my skin like a freezing ribbon. “You coming by with my meds?”

I took the tray from the maid like an offering. When he swallowed the pills from my hand, I smiled the way a good sister should, told him I would be his assistant at the company someday, and shut his door with a gentleness that I think read as love.

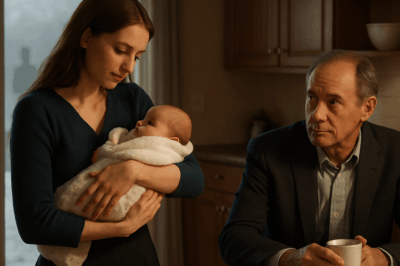

In the morning, I took Vivian to coffee.

He wants to kill you, I told her.

I pressed a debit card into her palm. A million dollars is a lot of leverage in a small town and just enough escape velocity in a big country. “Go,” I said, and meant it. “You deserve a life that isn’t this house’s echo.”

She blinked saltwater and pride. “Why?”

“Because you once danced a piece so beautiful it made me forget all of this,” I said, lying only in the direction of poetry.

She ran. Good for her. I needed the space.

When the kidnappers called—Ethan’s voice higher than usual, new and slick with practiced menace—I used my best telephone smile to soothe him and my worst memory of the woods to guide me. “I don’t have a hundred million,” I said. “I can bring fifty.” He hissed. In the background, Charles stammered bank-passwords. Margaret cried like a broken faucet.

Three days later, he told me where to bring the money: a pier that didn’t look like a crime scene yet.

I wore red lipstick so bright it looked like war paint and went to sea.

Part IV

The boat was a party-barge without the party, all sun-bleached benches and an outboard that coughed when it should have purred. Ethan’s lackey—a scarecrow with a graduate degree in following orders—patted his waistband in a manner meant to telegraph competence. It read as theater. Ethan sat in a camp chair like a dethroned king. The sky was the blistering blue of an American postcard—the kind that pretends the country was always innocent and is only ever angry to protect that innocence.

“Where are they?” I asked, a half-dozen kinds of seriousness in my voice.

Ethan smiled the smile of a man who thinks cruelty is a personality. He tapped his phone. On-screen: two bodies in a basement that could have been anyone’s. I didn’t ask for a timestamp. I already knew. He had been practicing this role—the avenger, the inheritor, the executioner—since he’d told a cop at a fence line that he was still a man, that his legs could do what his hands could not. Killing is a promotion in some boyhood mythologies; he got himself promoted.

“Thank you,” I said, and let the words land like pennies on a grave.

He flinched. “What?”

“Thank you,” I repeated calmly, stepping forward, a little breeze making my coat flutter like a banner. “They were obstacles.”

“You’re sick,” he said, but his eyes searched my face for the old sister who had wanted their love. He couldn’t find her. I had locked her in a box and slid the box off a cliff.

“I didn’t switch your meds,” I said. “I replaced them.”

“What?”

“Placebo, then panic,” I continued, “then the sound of Father’s voice saying what I needed you to hear. I made sure you walked past the study that night. I wanted you to hear them discussing the long-term facility. I wanted you to believe you’d be locked up, leashed, put away. I needed you sloppy. I needed you loud. Do you know why?”

He stared. His lackey shifted his weight in a way that made his weapon clink.

“Because in another life, you broke my legs,” I said. “Because I saved you and you rewarded me with a cage of bones and an audience of dogs.”

Ethan laughed. The sound came out like someone else’s cough. “Reincarnation?” he taunted. “Funny story, sis. Tell it again.”

“I stepped away this time,” I said. “I watched the semi take your arms, and I refused to save you. You called me a monster once for getting in the way of your hero script. I stopped getting in the way.”

In the corner of the deck, the lackey lifted his gun. In that moment, the air sharpened to a point. Time does this little daisy-chain-lace effect when you’re about to do violence: the edges of everything crisp up, and your memory puts bookmarks in places you wouldn’t expect. I remember a gull crying out. I remember the sun throwing knives off the water. I remember the lackey’s finger shaking.

I kicked his wrist the way Vivian had trapped Ethan’s shin—fast, low, decisive. The gun clattered, a stubborn echo. I slid mine from the holster at my back. My aim wasn’t perfect, but it was where it needed to be. He folded, in the quick, graceless way men fold when the muscles that hold their bravado together let go.

Ethan lunged at me with the petulant bravery of the very doomed. He tried to headbutt. I stepped. You move out of the way of trains and heads. My foot found his side with the kind of memory you carry in your bones. In another life, my femurs had splintered like chalk under his heel. I returned the favor across lifetimes.

“You think you can fight me without hands?” I asked softly, the politeness of it a special kind of sin.

He laughed again, a terrible, watery sound. “You did all this,” he said, almost admiringly. Then his face tightened into hatred so pure it looked like prayer. “You should die for what you’ve done.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But not today.”

I raised my gun and shot him. The sound cracked the horizon. For a second, the boat, the water, the sky—all of it—seemed to lean in.

When you kill the past, the present rearranges itself like furniture in a room after a flood. I moved without thinking. I checked pulses out of an abundance of caution that was really theater. I rolled bodies. I opened hatches. The sea is a maw that keeps secrets in a language only storms can read back to you. I fed it.

By the time the gulls settled in to talk about it, I was back on land, calling the detective I paid to disinfect stories. He was efficient, damp-eyed, overworked, and corruptible in exactly the ways I required. He nodded the way men nod when the dollar amount makes the ethics unnecessary.

Back in town, I signed things. I took things. I sold things. The Barretts had spent decades translating love into asset classes. I understood their language; I wrote a new poem in it. When the board asked about Ethan, I told them the facility had admitted him. When the board asked about Charles and Margaret, I told them they were in Geneva, then Florence, then St. Thomas. Wealth is an international dialect. It convinces people you are anywhere but the place where you could be questioned.

In the afternoon, I drove to the old airport, the one with the peeling mural and the coffee that tastes like pen caps. I sat at the gate with sunglasses on and a suitcase at my ankle and watched a child draw pictures of airplanes with a Bic. The mother apologized for the noise. I said I didn’t mind. I really didn’t. The boy drew a plane that looked like a boot and a sun like a flower. He was alive in the way children are before houses teach them which face to wear.

When my plane’s doors opened and the heat hit my face like a prophecy, I smiled. I had done terrible things. Some of those terrible things had names and some had only invoices. I walked toward the kind of life that allows you to become the least plausible version of your history.

In my pocket, my phone vibrated. A message from the detective: Clean.

I texted back a single word: Thanks.

There is a moment, in the shine between wrongdoing and consequence, where the world looks like a catalog: everything glossy, everything for sale, everything yours if you know which name to sign. I signed mine. Jenna Barrett. I said it like a dare, like I was testing a microphone. It rang true enough.

The thing about second lives is that the first one never shuts up. It mutters in the language of broken things. It says: you’re not this person. It says: you were once small and good. It says: at the Home, you learned how to make friends with people who flinched at thunder. It says: don’t forget the dogs.

I didn’t. I carried them with me like saints’ bones. They didn’t bless me. They just rattled when I walked and reminded me that even miracle stories leave bodies behind.

Part V

Abroad, the sun is the same. It burns through time zones as if clocks are un-American. I landed in a place where the beach smelled like sugar cookies and salt, and the hotel lobby smelled like wood polish and money laundering. I slept for fourteen hours. I woke up ravenous and ate fruit like I didn’t know what a grocery bill was. I raised a glass of sparkling water to my reflection and said, “To the future,” and it felt both cheap and perfect.

The money hit the accounts in drizzles and sheets. Some of it clean. Some of it scuffed. Some of it so filthy it felt like a dare. I put it where smart women do: in real estate that can’t disappear with a president’s tantrum, in art that appreciates when critics sigh, in funds that love an index more than a cowboy, and in a line item simply called “room to run.”

People will say I should have built a foundation. I will say foundations are for men who want their names carved on hospital wings and their sins laundered in a wash cycle labeled Philanthropy. I gave quietly: to the Home, to Vivian’s newly adopted dance kids in a city far from ours, to a shelter that took in women who left houses that made them small. I didn’t ask for plaques. I watched the receipts. I let the good work be their story, not mine.

That first week, I went down to the jetty every afternoon with a paperback and the kind of hat that means you’re tired of cabs slowing down. The sea was loud enough to drown out the memory reel. It tried. The reels play anyway.

In my head, the story insisted on arranging itself into a question that American morality loves: was I justified? I tried resisting the urge to answer the way perpetrators do, by reciting what victims did first. I could list it all: the broken femurs, the woods, the dogs, the names—viper, thief, not-daughter—the ignoring of Vivian when she needed a hand, the absolute worship of Ethan’s cruelty because it performed like masculinity on a stage with favorable lighting.

Then I heard the judge in my head—the kind the country loves to imagine, old and male and wise because he is old and male—ask the question without the moral spice: did you kill your brother? I could answer that one with a clean, unsentimental yes.

On day five, a man with careful shoes and a belt that whispered “consulting” sat down two beach chairs away. He had an American accent with a New England attic where the family heirlooms go. He was the sort of man who starts conversations because silence feels like poverty.

“Heading anywhere interesting next?” he asked, tapping his phone awake to check stocks.

“Anywhere with a good horizon,” I said, and watched the wave line breathe.

He nodded like we’d just shared a life hack. “You alone?” he asked after a beat, not predatory so much as curious in the way of men who assume women are either a wife or an RSVP.

“Yes,” I said.

“Brave,” he said, the way men say it when they mean odd, enviable, or for rent.

I smiled a polite smile that didn’t invite more. He returned to his indices. The market was green enough to earn the adjective healthy for a day and not enough to prevent someone somewhere from losing a house.

I thought of Charles, maybe on a tarmac in a country that allows you to pretend your crimes are just habits with nice shoes. I thought of Margaret, a woman born with gorgeously contained emotions who tried to raise a boy to believe that women exist to clap. I thought of Vivian in some city where she danced sweat into sheet music and remembered to breathe when she closed her eyes. I thought of Ethan not at all. That’s not true. I thought of him the way you think of a splinter you finally dug out. You still feel it for days. Then you don’t.

Two weeks in, I started running on the beach at sunrise. The first morning, my lungs resented me like teenagers. The third morning, they came along quietly. The seventh, they sang. People clapped for sunrises here. They set their iPhones on tiny tripods and introduced the dawn to their followers with breathless commentary. The American impulse to narrate itself never sleeps.

A month in, the detective’s folder arrived at a hotel desk under a name I’d given it: Green Roof. Inside: copies of the provisional death certificates for Charles and Margaret—pulled from an overworked coroner who had seen worse money than ours; a report “confirming” Ethan’s transfer to a long-term psychiatric facility where his name occupied a bed that in real life contained a man who muttered at the ceiling and thought he was a telephone; the kind of photographs that don’t prove anything and cost enough to make juries blink. I tipped the concierge in a quiet way that turned her nod into respect rather than thirst.

I read the folder at the bar under a light that made everything look expensive. The bartender—skinny tie, forearms with a roadmap of veins—made me a drink even though I asked only for tea. “On the house,” he said. Americans love trying out generosity like a hat.

“What’s this?” I asked, and he told me the ingredients with the seriousness of a surgeon.

“Thanks,” I said, and meant it, and didn’t drink it. I took my tea to the terrace and watched the sun lower itself with what people like to call dignity and what is really just gravity doing its reliable, magnificently unsentimental thing.

I dialed a number I’d memorized the way kids memorize locker combos. Vivian answered on the first ring. “Who is this?” she asked, because she’d learned things about numbers that don’t have names attached.

“Jenna,” I said, and braced against whatever sound would come.

She exhaled—relief, fear, a dance move inside a breath. “Are you—are you okay?”

“Better than okay,” I said. “How’s school?”

She laughed, the first time I’d heard it in so long the sound embarrassed me. “I’m dancing on a scholarship,” she said. “I’m cleaning at night. I’m sleeping in a place with a lock that works and a window that looks at a street no one we know walks down.”

“Good,” I said, and thought: I will not tell you the rest. She didn’t ask. Maybe she knew. Maybe she decided not to. Maybe she was learning the American art of leaving a story alone before it stains your shirt.

“Thank you,” she said. She put the weight of a life across those two words and didn’t overexplain.

“You’re welcome,” I said.

We didn’t say I love you. We didn’t say we’re sisters. The truth sat between us like a cat. It would come when it wanted. It might never. That was okay.

After we hung up, I walked down to the water where it lapped at the ankles of civilians. A toddler toddled. A woman with a book pretended not to cry. A man tried to sell me a bracelet with my name on it and I told him my name had too many letters. He said, “I can make it work.” I tipped him to leave me alone.

When I finally opened my journal, I wrote, in American English with an orphan’s neat block letters:

Ledger Closed.

Under it, smaller: Or, If Not Closed, Then Balanced Enough to Spend.

Endings in our country like to be tidy. They like bows. They like montage music. Real endings are footnotes that keep mutating. I kept running. I kept eating fruit I didn’t wash well enough. I learned how to order dinner in two other languages. I slept with a man whose kindness wasn’t an affect and whose politics didn’t require me to teach him history. We parted on a Tuesday with coffee on our breath and no regret because adults can do that and be fine.

And sometimes, at four in the afternoon, when the sun hit the water at an angle so sharp it made me squint at the brilliance, I remembered the sound of Ethan’s voice the night of the semi: “Why stop me from saving her?” as if heroism were a birthright instead of a practiced craft, as if women exist to be saved in a way that erases their capacity to run. I remembered stepping aside. I remembered the terrible, electric peace of letting a story rewrite itself and refusing to stand in the part of the plot where my bones were supposed to break.

That peace is not innocence.

It’s something better.

It’s a choice repeated across an ocean and a year and a lifetime, every time a woman in a country like mine refuses the script and writes a newer, meaner, truer one with the pen she stole and then bought and then engraved with her own name:

Jenna Barrett.

I wrote it on hotel stationery and on customs forms and on the back of a diner receipt when I left too much tip because the waitress called me sweetheart without stealing anything else from me. I wrote it in my phone when a bank asked me to verify an identity. I wrote it in my head when a nightmare woke me up with dogs’ breath too close and I had to remind my lungs that we were in a room with air-conditioning and locks.

On my last evening before I moved to a quieter coast, I took a cab to a hill where I could see the entire harbor. The driver asked me if I was married, the way cabbies do when they are trying to triangulate something that isn’t marital status. I said no. He nodded appreciatively, as if my answer were a map to a treasure he hadn’t decided whether to steal.

At the top, I tipped too much again. I stepped into the wind. The horizon did its old trick of pretending to be a line. It never is. It’s a smear if you look closely. So is justice. So is love. So is whatever we call what families do to one another when they’re afraid of who they really are.

I whispered, to no god in particular: “Amen.”

Not because I believed in forgiveness.

Because I believed in punctuation.

Then I went back to the hotel, packed my bag with the speed of someone who can leave anywhere faster than the police can learn a name, and slept the long, easy sleep of a woman who will wake to another airport, another sun, another morning where her bones belong to her and her ledger, for once, doesn’t.

The End.

News

After a passionate night, the American billionaire left the poor college girl one million dollars and disappeared. Seven years later, she finally understood why she was worth that much CH2

Emily Carter was twenty-one, a scholarship student at Columbia University who worked nights at a small Italian restaurant on the…

A Bank Manager Shamed an Elderly Man — Hours Later, She Lost a $3 Billion Deal CH2

On a humid Tuesday morning in Dallas, Henry Whitman, a retired steelworker in his late seventies, shuffled into Crestfield National…

He Threw His Wife and 5 Children Out of the House… BUT WHEN HE CAME BACK HUMILIATED, EVERYTHING HAD CHANGED! CH2

He had everything: a loyal wife, five children who admired him, and a house that looked like a palace, but…

“My hand hurts a lot! Please, stop!” cried little Sophie, shaking as she knelt on the cold floor. Tears ran down her red cheeks as she held her hand, the pain too much to bear. CH2

“My hand hurts so much! Please, stop!” cried little Sophie, trembling as she knelt on the cold floor. Tears flowed…

That Summer Day, Routine Shattered: Nancy Walked Into the Kitchen, Eyes Downcast, Cradling a Dark-Skinned Baby—Unaware of the Storm About to Break CH2

That summer day, the routine shattered. Emily walked into the kitchen, eyes downcast, a baby cradled in her arms. A…

Shut up while I give you money,’ my husband smirked, not knowing that in the morning security wouldn’t let him into his office: I would be the one signing the termination order. CH2

“I told you, I’ll handle this myself,” my husband snapped, tossing his coat onto the chair. The smell of expensive…

End of content

No more pages to load