Part One

When I showed the tattoo artist the design for my mom’s memorial tattoo, he stared at it for so long I thought maybe he’d fallen asleep standing up.

“You sure about this?” he finally asked, his voice low and uncertain.

“Yeah,” I said, smiling, though it felt forced. “She drew it herself before she died.”

He blinked slowly, still studying the image on the paper — interlocking triangles and spirals that looked kind of like a Celtic knot but sharper somehow, less flowing, more… rigid.

“Okay,” he said finally, voice tight. “If you’re sure.”

I nodded, because of course I was sure. It was Mom’s last sketch before the cancer took her. She’d always been an artist — the kind who filled every scrap of paper in the house with shapes, lines, and strange little doodles she claimed “helped her think.” When she gave me this one in hospice, she’d told me, “It’s protection, sweetheart. For both of us.”

So yeah, I was sure.

The artist, a tall guy named Brandon, worked in silence for the next three hours. No music. No conversation. Just the buzz of the needle and the smell of antiseptic. When he finished, he wrapped my shoulder quickly, avoiding my eyes. I tipped him fifty bucks extra — he’d done good work — and left feeling this strange mix of grief and pride.

That night, I texted my girlfriend, Olivia, that I was finally ready to show her. She’d been supportive through everything — the funeral, the long months of me trying to “move on.” She was the kind of person who brought comfort food without being asked. When I walked into the apartment, she was curled up on the couch with our cat.

“Ready to see it?” I said.

She smiled. “Of course.”

I peeled the bandage back carefully, proud of how sharp the lines were, how clean the ink looked even under the redness.

Olivia’s smile died instantly.

“What is that?” she whispered.

“The tattoo,” I said, laughing nervously. “You don’t like it?”

She backed up a step, her hand over her mouth. “Please tell me this is a joke.”

My stomach dropped. “What are you talking about?”

She didn’t answer. She grabbed her phone and went into the bedroom, shutting the door behind her.

That night she slept on the couch. I heard her whispering on the phone around 2 a.m., saying, “I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do.”

The next morning, she was gone.

I figured she just needed space. Grief made people act weird sometimes. I tried not to think too much about it as I got ready for work at the marketing firm. It was warm out, so I wore a tank top — my shoulder needed to breathe anyway.

When I walked into the office breakroom, my coworker Marissa saw me and dropped her coffee mug. It shattered across the floor.

“Oh my god,” she gasped.

“Sorry,” I said quickly. “Did I startle you?”

She didn’t answer — just stared at my shoulder like she was looking at a spider crawling on my skin.

“What?” I asked. “Is it that bad?”

She shook her head slowly and walked out without cleaning up the mug.

By lunch, HR had called me in.

“Ethan,” said the HR director, a woman named Karen who usually smiled too much. “We’ve had… complaints.”

“Complaints?” I laughed. “About what?”

She folded her hands on her desk. “Your tattoo.”

“My tattoo?”

She nodded. “You’ll need to keep it covered at all times. This is your only warning.”

“Karen, it’s a memorial tattoo for my mom,” I said, my voice cracking. “She drew it herself.”

Her eyes flicked toward the window. “Just keep it covered,” she said. “Please.”

That night, I posted a photo of the tattoo on Instagram with the caption “For you, Mom.” Within an hour, the post was gone. Deleted. Facebook took it down too. When I asked Reddit for help identifying the design, they banned me for “hateful content.”

I stared at my phone, my stomach twisting. What the hell was happening?

When I looked at the tattoo in the mirror, I saw the same thing I’d seen at the shop — just lines, triangles, spirals. Geometric. Beautiful.

What were they seeing that I wasn’t?

Olivia still wasn’t answering my calls, so I drove to her sister’s house. I stood outside the door knocking until she finally answered through the wood.

“Olivia, please. Talk to me.”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” she said, her voice tight.

“I don’t understand what’s happening.”

“The fact that you don’t see the problem is the problem.”

“What problem? It’s a drawing Mom made!”

Silence. Then, softly, “You need to get rid of it.”

“Tell me why!” I shouted. “Please!”

But the only sound that came through was the click of the deadbolt sliding into place.

By the end of the week, HR called me back in.

“I’m sorry, Ethan,” Karen said, eyes downcast. “We’re letting you go. Cultural fit.”

“Cultural fit?” I repeated, incredulous. “This is about the tattoo, isn’t it?”

She didn’t answer.

When I left the building, I felt hollow. I stopped by the grocery store on the way home. At checkout, my sleeve slipped up and a woman grabbed her kid and ran out of the store, leaving a full cart behind.

“Ma’am!” I called. “What do you see?”

But she was gone.

That night, I stared at my reflection in the mirror for hours. Every line of the tattoo looked the same — precise, symmetrical, meaningless. But the longer I looked, the more wrong it felt. Like the shapes were moving. Like something was hiding inside them.

I was exhausted, grieving, and now jobless.

When my dad called the next day, I nearly didn’t answer.

“Son,” he said slowly, his voice heavy. “Where did you get that design?”

“Mom drew it,” I said. “Dad, please, do you know what it means?”

He went quiet for a long time. I thought the call had dropped.

“You need to get that removed,” he said finally.

“What is it, Dad? What did Mom draw?”

His breathing changed — sharp, almost panicked. “She didn’t know what she was drawing. God, what if she did know…”

“Know what?” I demanded.

He paused. Then, softly, “There’s something you need to know about your mother.”

And that was how it began — the unraveling.

That night I couldn’t sleep. My dad’s words looped in my head. I kept staring at the tattoo until the lines seemed to shift under the bathroom light, the triangles interlocking like teeth. I thought about how Mom used to draw these shapes when she was deep in thought, her pencil moving fast and sure, like she was tracing something from memory.

But what kind of memory looked like this?

By dawn, I’d made up my mind. I was going to find out.

Part Two

My dad sounded different when he called that morning — quieter, older somehow.

“Meet me at the diner on Fletcher Street,” he said. “Two hours.”

“Dad, what’s going on?”

He sighed, the kind of sigh that comes from deep inside a person. “It’s about your mother. Just… come.”

Then he hung up.

The diner hadn’t changed since I was a kid. The same flickering neon sign that said OPEN 24 HOURS, the same smell of burnt coffee and syrup. Dad was already there, sitting in a booth near the back, a cardboard file box beside him.

He looked smaller than I remembered. The years since Mom’s death had carved deep lines into his face. When he saw me, he tried to smile, but it came out crooked.

“Hey, son.”

“Hey,” I said, sliding into the booth. My eyes went to the box. “What’s that?”

He pushed it toward me. “Your mother’s old notebooks. From her work days. I should’ve looked through them before, but…” His voice trailed off. “I guess I didn’t want to know.”

I pulled off the lid. Inside were spiral-bound journals, sketchbooks, and loose papers, all yellowed with age. Mom’s handwriting filled every page — neat, sharp letters, sometimes crowded by quick doodles in the margins.

The same shapes from my tattoo appeared over and over — triangles, spirals, lines that looped and connected like a maze. Sometimes she drew them small, tucked between words. Other times they filled entire pages, layered and overlapping until the paper looked like it was vibrating.

My throat tightened. “She was drawing these for years.”

Dad nodded. “Started after a case she worked in ’98. Child welfare. Some pretty dark stuff.”

“What kind of stuff?”

He rubbed his face. “She never gave me details. Said the kids had been through hell, and she couldn’t stop thinking about what they described. That’s when the drawings started. She said they helped her process the trauma.”

“Process it how?” I asked.

“She said it was like… putting the darkness on paper so it couldn’t stay in her head.”

I turned another page. The patterns got denser the further I went. They weren’t random — they meant something. The repetition was deliberate. Some were shaded in ways that made the triangles look like they were layered in three dimensions. The spirals tightened until they disappeared into black dots.

My stomach twisted. I pulled out my phone and searched geometric triangle spiral symbol meaning.

A few clicks later, I found an FBI awareness page on child exploitation and trafficking symbols.

When I saw the images, my hands went cold.

They weren’t identical, but they were close — close enough that I knew why everyone had reacted the way they did. My tattoo looked like a twisted combination of two symbols on that page, both associated with child predators.

I turned the phone toward Dad. His eyes widened, and he sank back into the booth.

“Oh, God,” he whispered. “I was afraid of that.”

I felt sick. “You knew?”

He shook his head quickly. “Not for sure. I just… I remembered hearing about those symbols when your mom was still working. Some of the kids in those cases described seeing them — carved into walls, drawn on documents. I think your mom started seeing them in her sleep.”

I stared at the notebook in front of me. My mother — the woman who had spent her life protecting kids — had unknowingly drawn the very thing she fought against.

“This was the last thing she drew,” I said quietly. “She gave it to me before she died.”

Dad’s eyes filled. “She didn’t know, Ethan. She couldn’t have known.”

I nodded slowly, though the truth felt like a knife twisting in my chest. “Then why does it feel like everyone else does know?”

That night, I couldn’t stop thinking about the look on Brandon’s face — the tattoo artist — when I’d first shown him the design. He must’ve recognized it. Maybe he hadn’t wanted to say anything, afraid of offending me.

I pulled up his shop’s website. It said Walk-ins welcome.

The next morning, I drove across town, parked outside the brick storefront, and walked in. Brandon was at the counter, talking to a client. When he saw me, he froze.

“I need to talk to you,” I said.

He hesitated, then nodded for the client to wait and stepped aside with me.

“Look, man,” he said quietly, “I don’t want trouble.”

“I’m not here for trouble,” I said. “I just want to know what you saw. You recognized the design, didn’t you?”

He ran a hand through his hair. “I shouldn’t say anything. But yeah. I recognized something. I thought maybe it was coincidence, but…” He lowered his voice. “That pattern — it’s not good, man. I’ve seen people cover up stuff like that before. Didn’t think you’d want to be one of them.”

“What is it?” I asked, even though I already knew.

He shook his head. “You should look up the FBI’s database on trafficking symbols. That’s all I’m gonna say.”

“I did,” I said quietly.

His face softened. “I’m sorry, man. Really. I could tell you weren’t trying to make a statement. You looked like a guy trying to honor his mom. But that symbol… it’s poison.”

I nodded, unable to speak.

“If you want it removed,” he added, “I can recommend a good laser clinic. They’re expensive, but it’s worth it.”

The clinic was called Advanced Dermatology. The receptionist booked me an appointment for Wednesday at 2:00 p.m. with Dr. Sophie Lowour. She sounded calm, professional — no hint of judgment in her voice, which was a relief.

Those three days before the appointment were some of the longest of my life. I couldn’t sleep. Every time I closed my eyes, I saw the pattern glowing faintly against my skin. I started wearing long sleeves even inside my apartment, as if covering it could make it stop existing.

When Wednesday came, I showed up early and sat in my car for twenty minutes, rehearsing what I’d say. It’s just a misunderstanding. I didn’t know what it meant. It was my mom’s last drawing.

When they called my name, my heart was hammering.

Dr. Lowour was in her 40s, dark hair pulled back neatly, expression composed. She asked me to remove my shirt, and I did, feeling the weight of her gaze as she studied my shoulder.

She didn’t flinch. Didn’t look disgusted. Just clinical.

“How long have you had it?” she asked.

“Three weeks,” I said.

“Any allergic reactions or complications?”

“No.”

She nodded, taking photos from different angles with her tablet. Then she explained how laser removal worked — how light would break up the ink particles, how the body would absorb them over time. Eight sessions minimum. $400 each.

I did the math and felt sick. $3,200. Minimum.

But she didn’t judge me. Not once.

“I can start today if you’re ready,” she said.

I nodded. “Do it.”

The first pulse of the laser felt like someone flicking hot grease onto my shoulder. The smell — burning ink mixed with something sharp and chemical — made my stomach churn. I clenched my fists and focused on breathing while Dr. Lowour worked in short bursts.

After twenty minutes, she switched off the machine and applied a cooling gel. “All done for today,” she said. “Keep it covered for forty-eight hours. Avoid sunlight and swimming.”

When I walked out to my car, my shoulder throbbed under the gauze. I caught sight of a woman getting out of her car two spaces over. She glanced at me, and for a split second, my chest tightened — that irrational fear that she somehow knew.

I drove home fast, hands trembling on the wheel.

That night, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I needed to understand more — not just about the tattoo, but about why Mom had drawn it. What she’d seen. What she’d lived through.

I opened my laptop and typed her name into Google: Claire Henley Child Welfare Services.

Pages of old newspaper clippings popped up — dated between 1996 and 2001.

“Local Social Worker Testifies in Trafficking Case.”

“Recovered Children Linked to National Investigation.”

“Henley’s Dedication Praised in Difficult Case.”

My mother’s name appeared over and over. She’d been one of the lead caseworkers in a series of high-profile child exploitation cases in the late ’90s.

I clicked article after article, my stomach turning.

One mentioned “disturbing symbols” recovered at the scenes.

Another said: Children described recurring geometric patterns used as identifiers by their abusers.

And there it was again — those same words, that same description.

Triangles. Spirals. Interlocking lines.

Mom had spent years listening to children describe those shapes — over and over. And when the cases ended, she’d started drawing them herself.

The next morning, I called Dad.

“She saw them,” I said flatly.

He was silent for a moment. “Saw what?”

“The symbols. The ones the kids talked about in those cases. She must’ve seen them so many times she started recreating them without realizing.”

He exhaled heavily. “I was afraid of that.”

“Why didn’t she tell me?”

“She was trying to protect you,” he said. “She didn’t want you to know the kind of evil she dealt with every day.”

“Well, now I do know,” I said, my voice breaking. “And I have it burned into my skin.”

He didn’t respond right away. Then, quietly, “I should’ve warned you, son. I should’ve gone through her things.”

“Yeah,” I said softly. “You should’ve.”

That night, I sat in my room surrounded by Mom’s notebooks, flipping through page after page of the same haunting geometry. I tried to make sense of them — to decode some message she might have left behind — but all I felt was this crushing sadness.

She’d drawn to cope. I’d tattooed one of those drawings to honor her. And somehow, I’d ended up carrying the symbol of the very monsters she’d fought to expose.

I picked up my phone again and searched lawyer wrongful termination cultural fit.

Because if I was going to lose everything over this, I wasn’t going down quietly.

The next morning, I found a lawyer named Jared Baker, who specialized in wrongful termination. His website said Free Consultations.

I emailed him my story. He responded within hours.

When I met him, Jared was younger than I expected — maybe late thirties, sandy hair, sleeves rolled up. His office was small but neat.

He listened without interrupting, occasionally jotting notes.

When I finished, he leaned back in his chair. “This is… complicated,” he said. “Cultural fit terminations are tough. Employers can argue they’re protecting other employees from discomfort.”

“Even if the discomfort is based on a misunderstanding?”

He shrugged. “Legally, intent doesn’t always matter. But public perception might. If we can show they acted out of panic without proper investigation, we might push for a settlement. Two or three months’ severance, maybe neutral references.”

It wasn’t much, but it was something.

I signed the papers that afternoon.

When I got home that night, my shoulder burned from the healing laser treatment. I sat on the bed staring at the mirror again. The tattoo looked faintly blistered, swollen around the edges — like it was trying to crawl out of my skin.

For the first time since Mom died, I cried.

Not for her.

For me.

For everything she’d carried in silence — and everything I was paying for now.

I didn’t know it yet, but that box of notebooks wasn’t finished with me.

Because buried in the bottom — under all those spirals and triangles — was something that would change everything I thought I knew about my mother.

Part Three

The box sat on my kitchen table like a live bomb.

I hadn’t opened it since that night at the diner. Every time I walked by, I felt it — the weight of it — like something waiting for me to dig deeper.

Three days after I met with the lawyer, I finally gave in. I pulled the notebooks out one by one until I hit the bottom, where a smaller folder was wedged underneath. It was labeled in my mom’s handwriting: “C.R. 98–B / Closed.”

The paper smelled faintly of mildew and something older, like dust and regret. Inside were newspaper clippings, copies of court transcripts, and typed reports stamped CONFIDENTIAL.

The first page started with the words “Child Recovery Unit – Case Report.”

I froze.

Mom had worked in social services, but I’d never known she was involved in recovery operations. I thought she just handled foster placements and home evaluations.

I kept reading.

The report detailed an investigation involving multiple missing children recovered from an abandoned property outside Sacramento. I skimmed line after line of bureaucratic jargon — multi-agency coordination, psychological debriefings, protective custody.

Then I saw Mom’s name in the witness list. Claire Henley, Case Worker.

Her written statement followed:

“The children repeatedly drew similar geometric patterns when asked to describe the environment. Triangles interlocked within circles. Spiral motifs. The same symbol appeared carved into the basement walls and drawn on documents recovered from the site.”

I read that paragraph three times.

The symbol she’d described was my tattoo.

I turned the page and found black-and-white photos attached with paperclips. Most were blurred or redacted — crime scene images I wasn’t supposed to see. But in the corner of one, faint but visible, was a shape scratched into a concrete wall.

Three interlocking triangles surrounded by spirals.

My breath caught.

Mom hadn’t invented that drawing. She’d seen it — over and over, burned into her memory through her work.

No wonder she couldn’t stop sketching it. No wonder it ended up on her deathbed drawing.

And no wonder everyone who saw it now reacted with horror.

It wasn’t just a hate symbol. It was something far older, darker — the mark of the worst kind of human cruelty.

I shut the folder and pressed my palms against my eyes until stars bloomed behind them.

She must’ve drawn it to process the trauma, the way soldiers write journals or addicts make art in recovery. She was trying to take power away from it. But I’d taken that same drawing and inked it permanently into my skin.

I didn’t sleep that night. I sat in the dark, reading the rest of her notes. Between the case files were personal journal entries — written in her careful cursive.

“The children describe voices. Symbols on walls. They say the symbols mean ownership. I told myself it’s superstition, trauma manifesting as pattern recognition. But I keep seeing them when I close my eyes.”

Another entry, written months later:

“Nightmares again. Always the same. The symbols turning. The triangles opening like mouths.”

That one made my skin crawl.

I kept reading until dawn, then shut the folder and just sat there, numb.

Dad called that morning.

“You okay?” he asked.

I hesitated. “She kept her case files.”

His sigh was long, weary. “I figured you’d find them eventually.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

He paused. “Because I didn’t want you to see what she saw. I thought if I kept that part buried, you could remember her for who she was before the work broke her.”

“Too late,” I said. “I’ve already seen it. And now I’m living it.”

“I’m sorry, son.”

“Sorry doesn’t remove a tattoo.”

Silence stretched between us until Dad said quietly, “There’s one more person you should talk to. Her old supervisor, Nia Robinson. She retired a few years back. She might still have records.”

“Do you have a number?”

“I’ve got her email somewhere. I’ll text it to you.”

When I emailed Nia that afternoon, I didn’t expect a reply. But she wrote back within hours:

Ethan, I remember your mother well. She was one of the strongest advocates I’ve ever worked with. I’m sorry you’re learning all this now. Yes, I recognize the symbol in your photo. It appeared in several trafficking cases in the late ’90s. I can share what I know, but you should prepare yourself. It’s unpleasant history.

She attached links to archived news articles and a few PDF documents.

I clicked one labeled “Recovered Symbols: Correlation Study.”

The document listed dozens of geometric patterns — triangles, spirals, circles — used as coded identifiers by abusers and traffickers. They weren’t just drawings; they were language.

The pattern on my shoulder had a name.

The Spiral Triad.

According to the document, it represented a “multi-generational network” — a group so large and organized that several symbols had been cataloged to track its hierarchy.

My tattoo was listed as a core emblem, associated with “ownership and initiation.”

I dropped my phone. My stomach churned so hard I thought I might vomit.

Ownership. Initiation.

I’d branded myself with that.

Nia’s email ended with an invitation to talk by phone. She said she’d explain how my mother became involved with those cases and why she’d probably started drawing the symbols.

I stared at my phone for an hour before calling.

She answered on the second ring. “Ethan?”

“Yes.”

Her voice was calm, practiced — the tone of someone who’d spent decades talking people through hard things.

“I know this must be difficult,” she said. “Your mother worked some of the worst cases we ever saw. She was assigned to interview several children who’d been recovered from a property connected to a larger trafficking operation. The patterns you’re describing — she saw them constantly. The children drew them in therapy sessions. They were carved into the walls where the kids were kept. Some had been tattooed onto the perpetrators.”

I felt a chill spread through my body.

“She started drawing them too,” Nia continued, “not because she wanted to, but because they got stuck in her head. It’s something we understand better now — vicarious trauma. She internalized the imagery. Her mind replayed it even when she wasn’t working. Those drawings were her way of externalizing it.”

I swallowed hard. “So she wasn’t part of it.”

“God, no,” Nia said quickly. “Claire was one of the good ones. But she carried more than she could handle. I tried to get her to take a leave of absence, but she insisted on seeing those cases through. When it was over, she transferred to adult services. That’s when the drawings really started — after she’d stopped seeing the kids.”

“So the symbol,” I said, my voice shaking. “It’s real. Recognized.”

“Yes. It’s real.” Her voice softened. “And I understand why people reacted the way they did. The FBI still uses that image in training materials. It’s instantly recognizable to anyone who’s worked in the field.”

I rubbed my shoulder, suddenly aware of every line burned into my skin. “I didn’t know,” I whispered.

“I believe you,” she said. “Your mother would too.”

We were both quiet for a while before she spoke again.

“You’re not the only one who’s carried fallout from that case, Ethan. None of us walked away untouched. But you have a chance to make peace with it — to do what your mother never got to do.”

“What’s that?”

“Let it go.”

After we hung up, I sat staring at the tattoo in the mirror. It was already fading from the laser treatment — patches of ink breaking apart under the skin — but the shape was still clear enough to make me sick.

I thought about all the people who’d seen it — Olivia, my coworkers, strangers — and how their fear had been justified.

It wasn’t superstition or prejudice.

They’d recognized the mark of evil, and I hadn’t.

I emailed Jared, my lawyer, updating him about what I’d discovered. He wrote back within minutes:

“Do not post or share that symbol anywhere. The more you distance yourself publicly, the better. Focus on removal and settlement. The facts are on your side, but public opinion isn’t.”

He was right.

I drafted a statement with Nia’s help — one that explained the situation without making excuses.

I wrote that my mother had been a child welfare worker, that the design came from her trauma, that I hadn’t known its meaning, and that I was undergoing full removal.

Nia reviewed it and edited my tone — cutting words like victim and unfair and replacing them with phrases like accountability and understanding the impact of unintended harm.

When it was done, it read like something a person could believe.

I posted it to social media with comments disabled.

Within an hour, it was everywhere — shared, discussed, dissected. Some believed me. Others called it damage control.

But I didn’t care. I wasn’t posting to win people back. I just wanted the truth out there.

The following week, Jared called with news.

My former employer had agreed to mediation.

We met in a sterile conference room downtown. The HR director avoided my eyes the entire time. Her lawyer said they were prepared to offer three months’ severance and a neutral reference letter.

It wasn’t justice, but it was closure.

After signing the papers, I walked out into the sunlight feeling lighter for the first time in weeks. I still had the mark, but at least I wasn’t jobless anymore.

That night, I celebrated with frozen pizza and cheap beer, sitting in my apartment surrounded by the notebooks that had destroyed and explained my life all at once.

When I was halfway through my second beer, my phone buzzed.

A new email.

From Nia.

Ethan, one last thing. You asked what your mother might have meant when she told you the design was “protection.” I think I can explain that now.

I clicked.

In the interviews, several of the children said they believed the symbols had power — that if they drew them, they could keep “the bad men” away. Your mother might have absorbed that belief subconsciously. She probably thought if she drew the symbol herself, it would lose its power over her. When she gave it to you, she might have truly believed she was passing along protection — not harm.

I stared at the words until they blurred.

Protection.

That’s what she’d said to me on her deathbed.

“It’s protection, sweetheart. For both of us.”

I didn’t sleep that night either.

Because I couldn’t stop wondering — what if, in her mind, she had been protecting me?

And what if, somehow, in trying to do that, she’d passed along something else entirely?

The idea settled in my brain like a splinter I couldn’t dig out.

The next morning, I woke up to find a faint rash forming around the edges of the tattoo — small red dots that burned under my skin. Dr. Lowour had warned me about irritation after the first session, but this looked different. The redness wasn’t random — it traced the lines of the fading design.

Almost like the pattern was trying to come back.

I called the clinic, but the receptionist said it was normal healing. She told me to apply the cream and keep the area clean.

I followed the instructions, but that night, I woke up sweating. My shoulder burned like fire. I stumbled to the bathroom mirror, pulled off the bandage, and froze.

The lines that had faded were darker again — raised, inflamed, forming the symbol like it had never been touched.

My breath came fast. “No,” I whispered. “No, no, no.”

I grabbed my phone and called Dr. Lowour’s emergency number. She answered groggily.

“It’s spreading,” I said, voice trembling.

“Ethan, calm down. That’s impossible. The laser breaks down pigment; it doesn’t—”

“It’s darker! I’m looking at it!”

She hesitated. “Send me a photo.”

I did. The read receipt appeared. Then three dots. Then nothing.

She didn’t reply.

I barely slept after that. Every shadow looked like triangles. Every sound made me flinch.

By morning, the inflammation had faded — almost like nothing happened. But the lines were definitely darker again.

I told myself it was an illusion, maybe scabbing, maybe swelling. But deep down, something colder whispered that it wasn’t.

That this mark didn’t just live under my skin.

It lived in me.

And my mother had known that — or at least, feared it.

That night, I sat at my desk staring at her old notebook again. On the last page was a line written in block letters:

SOME SYMBOLS ARE DOORS.

Underneath it, she’d drawn the design again — same triangles, same spirals — but this time, one of the triangles was open, like a keyhole.

I don’t know how long I sat there staring at it before whispering out loud:

“Mom… what did you open?”

Part Four

The morning after the rash, I woke up drenched in sweat. The room felt heavier somehow, the air thick like I’d been sleeping underwater.

For a second, I didn’t remember where I was — just the faint hum of my air conditioner and the ache in my shoulder. When I finally got up and turned toward the mirror, I froze.

The tattoo looked different again.

The lines were darker. Sharper. Cleaner than before the laser treatment — like it had healed in reverse overnight.

That wasn’t possible.

I touched it, half expecting the skin to be hot or blistered, but it felt normal. My fingers trembled.

I snapped a photo with my phone and zoomed in. The edges looked raised, like the ink was sitting on the skin instead of under it.

I tried to tell myself it was just swelling, a bad reaction, maybe pigment migration. But deep down, I knew what I was seeing wasn’t medical. It was intentional.

Something had changed.

I called the clinic again. The receptionist sounded calm, rehearsed — like she’d said the same line a thousand times.

“Ethan, it’s probably inflammation. Give it 48 hours.”

“No,” I said. “You don’t understand. The ink is back. It’s like it reappeared.”

She hesitated. “You should come in.”

“I’ll be there in an hour.”

Dr. Sophie Lowour met me in the exam room wearing the same blue scrubs, her expression professional but tight. She looked at the tattoo under the white light, leaning in close.

“That’s… unusual,” she said softly.

“You think?” I snapped.

She didn’t rise to it. “There’s no physiological mechanism for laser-treated pigment to reconstitute itself. The particles are broken down and absorbed by the lymphatic system. Once they’re gone, they’re gone.”

“Then how do you explain this?” I demanded.

She stepped back. “I can’t. Maybe the laser didn’t penetrate evenly.”

“It was gone.”

She looked up at me then, eyes sharp behind her glasses. “Ethan, has anyone else touched this? Applied anything to it besides the ointment I prescribed?”

“No.”

“Have you had any unusual symptoms? Fever, chills, hallucinations—”

“Hallucinations?” I laughed harshly. “You think I’m crazy?”

She didn’t answer. She just wrote something down on her tablet and said, “I’d like to run some tests. Skin biopsy, blood panel.”

I shook my head. “No needles. Not until I understand what’s happening.”

She hesitated, then handed me a card. “At least talk to someone. A trauma counselor. You’ve been under stress. Sometimes the brain…”

“I’m not imagining this,” I said, grabbing my shirt and leaving before she could finish.

I drove home in silence, gripping the steering wheel until my hands ached. The city looked normal — cars, sunlight, people walking dogs — but I felt completely detached, like I was watching through glass.

When I got back to my apartment, I locked the door and turned off the lights. The quiet felt safer.

I sat on the couch and opened one of Mom’s notebooks again. The pages fluttered in the breeze from the ceiling fan until one stopped halfway open.

The design on that page was different from the others.

Three triangles like always, but in the center she’d written a single word:

“LISTEN.”

I stared at it until my eyes blurred.

Then — faintly, so faintly I thought I was losing it — I heard something.

A sound like whispering.

Not words, exactly. Just murmurs. Soft. Urgent.

It seemed to come from behind me, but when I turned, there was nothing there.

The whispering stopped.

My heart hammered in my chest.

I didn’t tell anyone about the whispering. Not Dad. Not Nia. Not Dr. Lowour.

It came back that night — louder, closer. I tried blasting music, but it only seemed to hide underneath it, like static under a radio song.

When I finally fell asleep, I dreamed of triangles. Spinning. Interlocking.

In the dream, I stood in a concrete basement. The walls were covered in the same pattern. The spirals moved — turning slowly, pulling inward like drains.

And there was something inside them.

Something breathing.

When I woke, my shoulder burned like fire.

The tattoo glowed faintly blue in the dark.

The next morning, I called Dad.

“Can I come by?” I asked.

“Of course. Everything okay?”

“No,” I said, voice cracking. “I don’t think so.”

When I arrived, he was sitting at the kitchen table surrounded by Mom’s photo albums. He looked up, startled by how pale I must’ve looked.

“Jesus, Ethan. You all right?”

I pulled off my jacket and showed him my shoulder. “It came back.”

He stared, eyes wide. “That’s impossible.”

“Apparently not.”

He reached out, fingertips hovering over the lines but not touching. “God help us,” he whispered. “She used to talk in her sleep, you know. Said she saw things when she closed her eyes. Faces in the spirals.”

I sank into a chair. “Dad, do you think she… brought something back with her? From those cases?”

He shook his head. “I don’t know. But she was never the same after that last one. Always sketching, like she was trying to trap something on paper.”

“Trap something?”

He nodded. “She said the drawings kept it quiet.”

My blood ran cold. “Kept what quiet?”

He didn’t answer.

That night, I slept at Dad’s house. Or tried to. Every creak made me flinch. Around 3 a.m., I felt something cold brush my neck.

I sat up fast, heart pounding.

Nothing. Just moonlight spilling through the blinds.

But when I looked down at my shoulder, I froze.

The tattoo was moving.

The spirals were shifting — slow, liquid, almost imperceptible — but definitely moving.

“Dad!” I yelled.

He stumbled in, bleary-eyed. “What is it?”

I pointed at my shoulder. “Look!”

He leaned closer. His face went pale. “Dear God…”

We both watched as one of the lines twitched — a slow pulse, like a heartbeat.

He stumbled back. “That’s not possible.”

“I told you something’s wrong.”

He looked at me, fear cutting through his expression. “We need to destroy it.”

“How?”

He hesitated. “There’s a bonfire pit out back.”

I almost laughed. “You can’t burn a tattoo, Dad.”

He ran a hand through his hair. “Then we burn what started it.”

We went to the garage. He brought out the box of notebooks, the folder, everything.

“I can’t look at these again,” he said. “They’re poison.”

We carried them outside. The night was cold, the sky clear. Crickets buzzed faintly in the distance.

He doused the pile with lighter fluid and handed me the matchbook.

“You do it,” he said quietly.

My hands shook as I struck a match. The flame flared bright, warm against the wind.

For a second, I hesitated. These were the last pieces of her. The only tangible connection to her mind.

Then I thought of the whispering, the glowing lines, the way the ink seemed alive.

I dropped the match.

The fire whooshed up fast. Pages curled, ink blackened. The smell was acrid, thick.

Dad and I stood there in silence, watching the paper crumble to ash.

When the flames died down, I thought I felt something shift — not in the air, but in me.

The whispering stopped.

For the first time in days, the world felt still.

But peace didn’t last long.

Two nights later, I woke up with my shoulder burning again.

When I turned on the light, I saw fresh lines on my arm — smaller versions of the tattoo, faint but spreading downward, branching toward my elbow.

Like roots.

I nearly threw up.

I ran to the bathroom sink and scrubbed until the skin bled, but the marks didn’t budge.

When I looked up, the mirror fogged slightly — and words appeared in the condensation, written backward.

SOME SYMBOLS ARE DOORS.

I stumbled back, slamming into the wall. “No,” I whispered. “No, no, no—”

My phone buzzed then, jolting me. Unknown number.

I almost didn’t answer.

“Ethan?” a voice said — low, female, familiar.

“Nia?”

“Yes. Listen carefully. I’ve been reviewing something from the archives. There was a reason your mother fixated on that symbol. It wasn’t just trauma. There were patterns of behavior — auditory hallucinations, sleep disturbances — same as you’re describing.”

“What are you saying?”

“She believed the symbol wasn’t just a mark. She thought it was an invitation.”

I swallowed. “An invitation to what?”

“Not what,” Nia said quietly. “Who.”

The line crackled.

“She used to say,” Nia continued, “that the children told her the symbol wasn’t drawn — it was copied. That it came from somewhere else. From something that listens when you look at it too long.”

The line went dead.

That night, I tore the gauze off my shoulder and stared into the mirror again.

The tattoo shimmered faintly under the light — not glowing exactly, but reflecting in a way skin shouldn’t.

I thought of Nia’s words. Something that listens.

Against my better judgment, I traced one of the lines with my fingertip.

It felt warm.

And for the briefest second — just a flicker — I heard my mother’s voice.

“It’s protection, sweetheart. For both of us.”

Then something whispered back:

“No. For one of us.”

I stumbled backward, hitting the sink. My knees went weak.

The whispering wasn’t in the room. It was inside me.

I grabbed the first thing I could find — a kitchen knife — and pressed it to the edge of the tattoo, desperate to cut it out.

The second the blade touched skin, a sharp pain exploded through my shoulder and a voice screamed in my head — not human, not words, just a roar of static and fury.

I dropped the knife, gasping.

The reflection in the mirror smiled.

But I wasn’t smiling.

By morning, the new lines had stopped spreading. My shoulder looked raw, inflamed, but stable. I tried to convince myself it was over — a psychotic break, stress hallucinations, anything but what it felt like.

Then an email came in.

From Nia again.

Ethan, I’m sorry for last night. The call cut off suddenly. I need to see you in person. Please meet me tomorrow at 5:00 p.m. at the old county offices on Jefferson Street. Bring any remaining notes or drawings. Do not look at the tattoo in mirrors or reflective surfaces until then.

That last sentence made my stomach turn.

Don’t look at the tattoo in mirrors.

I shut my laptop and turned every mirror in the apartment toward the wall.

Still, I could feel it pulsing beneath the bandage — faint but steady.

Like it was waiting.

The next evening, I went.

The old county building was mostly empty, windows boarded, vines creeping up the sides. A faint “For Lease” sign hung crookedly near the door.

Nia stood by the entrance, bundled in a gray coat. She looked older than I’d expected, but her eyes were sharp.

“Ethan,” she said softly, “thank you for coming.”

“What’s happening to me?” I asked.

She hesitated. “You’re not the first. There were others connected to those cases — investigators, social workers — who started experiencing symptoms after prolonged exposure to the symbols. Nightmares, hallucinations, compulsive drawing.”

“You think it’s contagious?”

“Not in the medical sense,” she said. “In the memetic sense. Like an idea that infects the brain. The children called it The Pattern That Remembers. They believed it marked those who understood it.”

I shook my head. “That sounds insane.”

“I know.” She looked at me sadly. “But tell me you haven’t felt something since you got that tattoo.”

I couldn’t answer.

Nia nodded slowly. “Then you understand.”

“What do I do?”

She looked down at my shoulder. “You finish what your mother started. She tried to contain it — draw it, bind it, pass it to someone who could destroy it. But she didn’t realize the act of giving it to you… passed it on.”

“Passed what on?”

Nia met my eyes. “The memory of what those children saw.”

Before I could respond, a sound echoed through the hallway — a low hum, like air moving through a pipe.

Then the lights flickered.

Nia’s face went pale. “It’s here.”

“What’s here?” I whispered.

“The thing that listens.”

The lights cut out.

Part Five

The lights in the old county building flickered once, twice — then died completely.

The hum in the air grew louder, vibrating through the floorboards. It wasn’t sound exactly, but a feeling — like the moment before thunder, when the air holds its breath.

“Stay close to me,” Nia whispered.

My pulse hammered in my throat. “What’s happening?”

“The pattern,” she said. “It reacts to awareness. The more you see it, the more it sees you.”

I wanted to laugh, but terror froze it in my chest. “That’s insane.”

She didn’t argue. She just turned on her phone’s flashlight, the small beam cutting through the dark. Dust motes danced in the light like ash.

The hallway ahead seemed endless. On the far wall, something was moving — faint geometric lines shimmering under the peeling paint.

Triangles. Spirals. Circles.

The same design as my tattoo.

Only now it covered the wall.

And it was breathing.

I stumbled back, hitting a desk. The flashlight flickered, and for a split second the pattern shifted — the spirals pulsed inward like the surface of water disturbed by a drop.

A low voice murmured through the static of the dark. I couldn’t understand the words, but I felt them — a pull deep in my chest.

Nia grabbed my arm. “Don’t listen to it!”

The voice grew clearer: Ethan…

My name.

The same tone my mother used when I was little.

“Mom?” I whispered.

Nia tightened her grip. “It’s not her.”

But part of me didn’t believe that. I felt her presence in that sound — sorrow, exhaustion, something like apology.

I stepped closer.

Nia tried to stop me, but I shook free. “I have to know what she was trying to do.”

The air around the wall shimmered. The pattern began to rotate, slow and deliberate. My shoulder burned, matching its rhythm.

It was like my tattoo was answering it.

Lines of faint light crawled down my arm, connecting to the shape on the wall — thread-thin beams that pulsed with each heartbeat.

For one horrifying instant, I realized the wall wasn’t solid anymore. The spirals were opening inward, like a hole cut through reality.

Nia’s voice came from far away: “Ethan, she drew it to contain it. That’s why she gave it to you — to trap what she couldn’t destroy.”

I barely heard her. My mother’s voice was louder now, clearer.

“I’m sorry, sweetheart. I needed someone strong enough to finish it.”

The light from the wall spilled across the floor, turning everything silver-blue. My arm trembled as the burning intensified. The triangle shapes on my skin cracked open, bleeding faint light instead of blood.

Nia was shouting something, but her words dissolved into the noise.

I understood, finally, what my mother had meant by “protection.”

It hadn’t been protection from evil.

It had been protection of it.

She had locked something away inside the pattern — and when she died, I released it.

Now, if I didn’t finish what she started, that thing would never stop finding new doors.

I pressed my hand against the wall. The surface was warm, pulsing like skin.

For a second, I saw flashes — a hospital room, my mother sketching frantically; children’s drawings spread across a table; a courtroom full of faces blurred by light.

Then, behind all of it, a shape — tall, shifting, formless — something that looked back.

“Mom,” I said, voice breaking. “What do I do?”

Her voice whispered through the roar: “Close it.”

“How?”

“With what carries it.”

I looked down at my arm — at the symbol glowing through my skin.

Of course.

If it had entered through me, it had to leave the same way.

Nia must’ve realized what I was thinking because she shouted, “Ethan, stop! You don’t know what it’ll do!”

“I know what it’s already done,” I said.

I pressed my palm flat against the center of the spiraling light. The heat was unbearable, burning through to bone. The lines on my arm blazed white, connecting to the wall.

The roar turned into a scream — not from me, not from Nia — from inside the light itself.

Then everything exploded in brightness.

When I woke up, it was dawn.

The building was quiet. Sunlight streamed through broken windows. My shoulder throbbed, raw and bandaged — Nia must’ve wrapped it while I was out.

She was sitting across from me, her face streaked with soot.

“It’s gone,” she said softly. “The wall’s clean. No pattern.”

I looked down at my arm.

The tattoo was gone too — not faded, not burned — gone. Smooth skin where it had been.

“What happened?”

“You closed it,” she said simply. “Whatever your mother sealed, it’s finished now.”

I stared at my bare shoulder, feeling empty and relieved all at once. “Is she…?”

Nia smiled faintly. “I think she can rest now. And so can you.”

A month later, I moved to a small apartment near the coast. I started therapy. Picked up freelance work. Rebuilt what little life I had left.

Sometimes, when I couldn’t sleep, I’d drive down to the water and watch the tide come in. The ocean was all spirals too — endless circles folding back into themselves — but it didn’t scare me anymore.

I got a new tattoo, small and simple, on the opposite shoulder. An oak tree — Mom’s favorite. The artist asked if I wanted any geometric work, and I almost laughed.

“No,” I said. “No more patterns.”

Six weeks later, a letter came in the mail with no return address. Inside was a single page of notebook paper.

Mom’s handwriting.

“Some symbols are doors.”

“Others are locks.”

“Thank you for closing mine.”

I folded the letter carefully and slipped it into my journal.

That night, I dreamed of her — sitting under an oak tree, sunlight on her face, sketchbook closed in her lap. She looked up at me, smiling the way she used to before everything broke.

For the first time in years, there was no fear in her eyes.

And when I woke up, there was peace in mine.

THE END

News

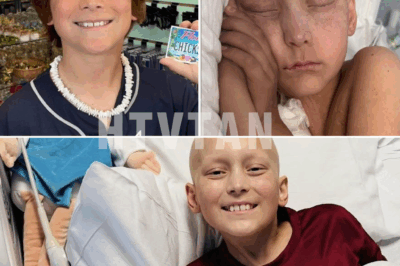

Hazel, a brave little warrior, faced another grueling week… CH2

Hazel’s Brave Battle: A Tiny Warrior Facing Fever, Chemo, and Sleepless Nights. Hazel, a tiny but incredibly brave warrior, faced…

Nichole Blevins has written words no mother should ever have to write. Her brave, hilarious, strong boy — Branson — is nearing the end of his battle with brain cancer… CH2

A Mother’s Final Goodbye — Branson’s Courage in the Face of the Unthinkable. This is a modal window. The media…

It started with a slur in his speech — then confusion, disorientation, and fear. Within hours, Branson could barely form words, his bright eyes clouded with pain… CH2

The Battle Beyond Cancer: Branson’s Struggle to Live Again. Three days ago, everything shifted. What began as a faint slur…

They had just received the kind of news no parent ever wants to hear… CH2

Waiting Between Fear and Faith — Branson’s Fight for Tomorrow. The night was still.Only the steady hum of machines and…

Everett Stephens is a brave little boy whose laughter and hugs bring joy to everyone around him… CH2

A Family United by Love: Everett’s Brave Journey Against Cancer… If you have ever crossed paths with the Stephens family,…

Austin and Aubrey Hall are two brave siblings who have faced incredible heart challenges since birth… CH2

Courage Runs in the Family: Austin & Aubrey’s Heart Journey. Austin and Aubrey Hall are not just siblings—they are warriors,…

End of content

No more pages to load