Part I

I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile Madison’s mother gave me in our kitchen, or the way her sister kept her face down in her phone like there was an audience in there I wasn’t invited to. It was Madison herself—soft brown eyes, hands sliding across mine on the countertop, voice pitched careful—“They really want you there this time, babe. Dad says he feels like he doesn’t know you. Please. It would mean a lot.”

Three summers running I’d dodged the family’s “annual cabin retreat.” The first year I had a transmission on sawhorses and a deadline that wouldn’t blink. The second, a busted alternator on a neighbor’s truck that turned into a neighborhood rescue and a long night that felt like a win. The third, I pretended the flu and lay on the couch with a blanket over my face while the NFC Championship roared like a party I wasn’t at. I love quiet. They love noise. It’s nobody’s fault until it is.

But a man raised to keep his word doesn’t shrug off a request said soft like that. I nodded. “All right, Mads. I’ll go.”

That’s how you step through a door you think is painted with welcome and find out the paint covers something else.

The ride up told me everything, but I wasn’t listening yet. They’re usually a show: football takes so hot they steam the windows, gossip about the neighbor’s fence line dispute that turns into a closing argument, a chorus of laughter that never once requires an actual joke. This time it was clipped talk about gas prices and the weather, broken by silences you could slice and serve. Her brother, Colt, leaned forward from the back seat more than once and put his mouth to Madison’s ear, and she stifled a laugh like a kid in church. Her sister’s eyes flicked up into the rearview at me—quick, sharp, gone.

“Feels like we packed for an army,” I tried, nodding at the coolers stacked like Tetris in the trunk. I like a joke you can roll like a ball across a room and see if anyone will toss it back.

Her dad, Ray, caught my eyes in the mirror. “You never know how long we’ll be out here,” he said, voice salted with that fake warmth men use when they’re about to tell you something that isn’t advice.

They’d bragged about the forty acres my whole marriage like they’d cleared every tree with their bare hands. The cabin came into view near dusk—a two-story log thing with a porch like a jaw, pines huddled around it as if the land had been told to stand at attention. Wiley orange light in the windows. Silence riding in the car like a fifth passenger.

Cell service cut out five miles back, my phone demoted from lifeline to camera. Inside, the place smelled like cedar and Pine-Sol. The pantry was stocked like a bunker: beans, rice, ramen bricks stacked in towers; bottled water in cases, a whole chord of firewood laid neat out back. The generator sat in the corner like a faithful dog. I knocked a knuckle on the pantry shelf. “What’s the plan, folks? Expecting the world to end while we’re here?”

Elaine, my mother-in-law, smiled the tight church-social smile that didn’t reach her eyes. “Oh, you know your father-in-law. Always overprepared.”

Dinner tasted like something plated for TV—too much garnish, not enough soul. Everyone was too cheerful, insisting I eat more, drink more, relax. Madison sat close, but her thigh never touched mine. She laughed loud at Colt’s stories like he was auditioning for a part I didn’t know existed. Something coiled and low in my gut. Suspicion hums—it doesn’t ring. I swallowed it with beer.

When Ray stood to raise a glass—“To new traditions”—the table clinked mine just a little too hard, like they wanted to see if the crystal would chip.

I forced a smile against teeth that had decided not to join in. Whatever tradition they were building, it wasn’t mine. Out there in the pine hush, the punchline waited.

The morning started polite—sunlight carving hard yellow into the curtains, coffee ghosts in the kitchen air. I heard the thunk of doors and the scrape of coolers, the kind of sounds a house makes when it exhales company. I figured we were packing for a hike. I stepped onto the porch to see bags being hauled into the trunks of both SUVs, hands moving fast like somebody was late for a flight.

“What’s going on?” I asked to the air more than to a person. Madison stood off to the side, arms crossed like she was hugging herself, eyes on the dirt. Colt held his phone out at an angle, a cameraman filming a reality show he was the only subscriber to.

“Oh, he doesn’t know yet,” Colt sing-songed. “This is gold.”

Ray turned toward me wearing a grin too big for his face. I’ve seen game show hosts less delighted by money falling from a ceiling. “You’re staying,” he said. “A little character-building exercise.”

“Excuse me?” I blinked. Like a man waking up to a wrong voice in the bedroom.

“It’s just for a while,” Madison murmured without looking up. “We thought it might be good for you. To prove something.”

Prove what? That I could be humiliated in front of the people who were supposed to be my family? That I’d chase a bumper down the mountain? That’s when I realized the man they’d always wanted me to be lived entirely in their head.

“You’ll thank us someday,” Ray said, smile not budging. “Men are made in solitude. Fire tempers steel.”

“Survivor: Cabin Edition!” Colt laughed, sweeping the camera, zooming in on my face. “Watch him cry in three days when the beans run out.”

I didn’t move. Didn’t rise. Didn’t give them the theater they wanted. I sat down on the top porch step, wood warm from new sun, and let their circus march past. “You can’t be serious,” I said finally, low enough to make a man lean in if he wanted to be sure.

“Oh, we’re serious.” Ray’s grin holden-plated. “We’ll be back to check on you.”

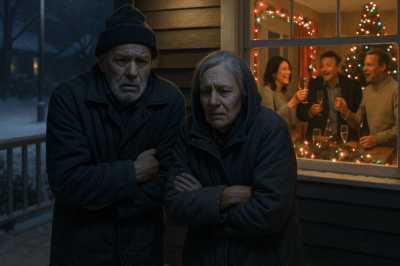

Engines fired. Gravel pinged like little insults under the tires. Madison glanced up once—quick, sharp—like she was fishing for a break in my face she could interpret as a sign. I leaned back on my elbows, crossed my ankles, and watched them shrink down the little ribbon of road. The dust hovered like an afterthought.

If you’ve ever been in a room where the bully leaves, you know the kind of silence I mean. Not peaceful. Heavy. The kind of quiet that expects you to fill it and punishes you if you do. No birdsong yet, like the woods wanted to see how I’d handle it. The faint echo of my own heartbeat in my ears.

Most men would’ve shouted. Run after the SUVs. Demanded answers. Begged. That’s what the camera wanted—Viral Husband Breaks Down, Weekender Edition. I pulled a cigarette from my pocket, lit it, and let the smoke curl up into the still morning like a slow prayer. I wasn’t broken. Not even angry yet. Anger’s a kind of energy you can waste like gasoline left open on a hot day. I needed mine.

I thought back to all the little digs I’d filed under “They don’t mean it”—Elaine’s helpful comments about how “some men are meant for handwork, and thank God for that, even if the pay is… what it is.” Her sister Lacey’s jabs about my being too quiet at family dinners—“It’s like eating with a very polite ghost.” Madison rolling her eyes when I’d rather stay home and fix what needed fixing than go drinking with her friends. They thought they were shaping me. What they were chiseling at was their own mask.

The cigarette burned down to the filter. I flicked it into the dirt, stood up, and looked at the cabin. Solid. Stocked. A roof that didn’t leak. Water that came up clean and cold from the pump. Firewood stacked like a promise. They thought they’d strand me. Standing there in the silence, I realized the strangest thing: I wasn’t stranded.

They were. They were stranded in a shallow game where the prize was belonging to people who needed you smaller to feel taller. They were stranded in a house of laughter that turns mean if you don’t clap on cue. They were stranded in the need to control a man so they didn’t have to look at the ways they’d failed to control themselves.

I went inside and shut the door. The quiet settled over me like good armor—weight in the right places, room in the shoulders to move.

The first night alone, I thought sleep might fight me. I expected the walls to scoot in, to press on my ribs the way rules do when they’re written by someone else. Instead, I sat by the fireplace with a dented pot warming a can of chili and a glass of well water sweating beside it. In the desk drawer I’d found a leather-bound journal brittle at the edges, the kind of thing you can’t buy made, only made by time. A hand—man or woman, it doesn’t matter—had filled it forty years back with notes on planting times, hunting luck, weather that told a story if you watched it. No philosophy, just the stubborn facts that keep a life standing upright.

I read the notes about pea shoots and late frost like scripture. I felt more kinship with that writer than with anyone who shared my last name through marriage. A simple thought sat down with me and refused to leave: A man who writes down when to plant and when to harvest isn’t trying to impress anyone. He’s trying to leave the world in a shape someone else can work with.

I slept like I’d been poured into the couch. Woke with the kind of hunger that felt like a reset. There’s a rhythm to work that I’ve always understood better than conversation. I took an axe to the rounds stacked out back and let my body remember what honest tired is. The bite of steel, the twist of the wrists, the grunt of wood giving up—every swing a note in a song men have been singing since kindling learned how to listen. Sweat rolled down my back. My hands stung. The stack grew. Nothing about it felt like punishment.

The second day tasted like coffee boiled wrong and bread toasted on cast iron. There’s a difference between quiet that’s a punishment and quiet that’s a gift. By midday I could hear the birds again, little test balloons of sound. The creek somewhere down the slope threw its voice through the trees. The cabin creaked in the afternoon heat like it was whispering to itself, bones settling deeper into the earth.

On the third morning I wandered up an old skid road just to stretch my legs and found the one spot where trees pulled back like curtains to let a bar of satellite through. My pocket buzzed like a hive waking. I held the phone up and watched a new world fall in: texts from Madison—Hope you’re not mad. This is for fun. Don’t take it so seriously. Are you OK? Dad says this is good for you—the words shrunk and grayed in chains. Two missed calls from Elaine. A handful of notifications from Colt’s social—“Season premiere,” selfies of him in reflective sunglasses with captions that dared people to laugh along or admit they were the kind of person no one invited anywhere.

I stared at the screen until the letters blurred. That’s the problem with people who make humiliation a hobby: they never admit they’re playing a game you never agreed to. Hope you’re not mad, like she’d spilled a beer on my jeans. Not left me alone three hours up a mountain miles AWAY from my life as a joke.

I put the phone back in my pocket, the buzzing like a mosquito I’d outlast. Walked back down to the cabin. Stirred beans. Mended a drawer. Read three pages of a journal written by a stranger who might as well have been my teacher. Slept.

Day bled into day and instead of feeling wild and loose, time got specific. Morning had a sound (jays arguing; the pump handle squealing itself awake). Noon had a taste (the first tomato out of a can on bread with salt). Evening had a color (firelight leaking out between my fingers when I held my hands up to the glow like a kid). I hadn’t checked a clock since the SUVs vanished. No deadlines. No meetings. No compulsory laughter. The silence wasn’t hollow; it was full.

And then, under the sun-bleached tarp behind the shed held down by two tasteful stones, I found the thing that made all the difference. A Honda motorcycle, early eighties by the look, paint faded to a color you can’t buy, tires sagged, a mouse nest under the seat. But the bones were good—steel frame, lines that spoke a language I knew. Most folks would’ve pointed, said “junk,” and snapped a photo. I saw the opposite. Possibility.

I wiped dust off the tank with my shirt like a man blessing a baby. Pulled the plug. Checked for spark. Siphoned the varnish-smelling gas, rinsed the tank, poured in fresh, shook it like a cocktail, drained again, refilled. Cleaned the carb jets with a bristle, a trick I’ll take to my grave. Greased the chain. Tightened bolts until the whole thing felt more like itself.

At dusk I kicked it. Once. Twice. The third time the engine coughed like an old smoker clearing his throat and then settled into a throaty chatter that made my chest hum. I revved it, revved it again, and grinned so big it felt like my face might remember this expression as normal again.

Madison’s family had thought I’d be rationing beans and talking to the walls by day three. Instead, I had a machine that could eat miles.

The next morning I rolled down the dirt track like a kid sneaking out of a house where bedtime was a suggestion he didn’t care for. Gravel chirped. Pine needles made their hush. The wind woke my skin. Fifteen miles of forest road and then the trees fell back to reveal a strip of town you could miss if you blinked wrong: a diner with a neon coffee cup, a general store that sold worms and bread and toothpaste and gas, a station with one pump forever over the line and yet somehow exactly whatever you needed.

The diner bell jingled like a laugh that didn’t judge. The air smelled like bacon grease and coffee. Truth smells like that. The woman behind the counter had a red bandana in her hair and an expression that said she’d seen every version of a man coming in from the woods and knew which ones to trust. “Coffee?” she asked.

“Strong as you got,” I said.

She poured, slid the mug. “You from up at the cabin?”

I raised an eyebrow. “News travels.”

“Town that small.” She leaned a hip against the counter. “You look like a man who knows his way around a grill. Mornings we could use a hand. Breakfast rush. Short order. Not glamorous, but it’s a paycheck and the crew doesn’t talk just to hear the sound bounce off the walls.”

I looked at the chalkboard menu. At the old man in the corner reading last week’s paper like it was hot. At my hands wrapped around a mug that said World’s Okayest Dad though I am no one’s father. I thought of the texts I wasn’t answering and the way silence tastes when it’s chosen. “When do I start?”

“Tomorrow,” she said, no ceremony. “Apron’s clean. Flat top’s grumpy until she warms up.”

When I rode back to the cabin, gas on my breath and bacon under my fingernails, my phone lit up like Times Square. Seventeen new messages. Ready to come home? Bet you’re tired of beans by now. Call me. Call me. Call me. I stood with the phone in my hand for a long minute, thumb hovering like a man about to push an apology across a bar he doesn’t actually owe.

I pressed and held. Click. The thread disappeared. The air in the room changed like the house had just learned a new language.

I set the phone face down on the table. Lit a fire. Sat with the journal and the kind of tired you get when the work you did that day and the man you are at night line up. They’d left me miles away from home as a joke. The punchline had found a different target.

The next ten sunrises I woke before the birds and rode the Honda into town to flip eggs and wrestle bacon while the flat top grumped its way from cold to ready. I learned the orders of people by their boots. I learned small talk that doesn’t lie. I learned that when you put toast on the plate so the butter melts instead of skates, a man will look at you like you’ve done him a favor that counts.

Every buzz of the phone those ten days was a test I let go unanswered, a lure I let pass. On the eleventh night, by the fire with the journal open to a page about when the snow usually gives up, I answered when her name lit the screen—not because I owed Madison anything, but because I wanted to hear the shape of her voice when the joke stopped laughing.

“Finally,” she breathed, relief like a rope she threw toward the line. “You scared me half to death. Are you okay?”

“I’m better than okay.” I leaned back, watched flame lift and lay down. “Got a job. Sleeping. Eating. Thinking.”

Silence like glass. “Wait. What? You’re supposed to be at the cabin.”

“I am. I’m not stuck.”

“You’re acting like a child,” she snapped, that switch-flip I’d known and named and excused for years. “This was never meant to be permanent.”

“Madison,” I said, letting the word find its own weight, “that’s the problem. With you, it was never meant to be anything I chose.”

She inhaled, the long way in a fight where someone realizes the rules are different than they remembered. “You need to come home. This is embarrassing.”

I laughed once—low, not cruel, just done. “Maybe you never knew me well enough to decide who I am.”

The line went quiet like a stage where the actors forgot their lines at the same time.

“I’m thinking clearer than I ever have,” I said. “And I’m not walking back into a room where the only way for you to feel tall is for me to make myself small.”

Some truths don’t need to be shouted. They hang in the space like a quilt you just finished and realize you’ll sleep under for years. When we hung up—not because either of us slammed anything, but because the conversation ran out of places to go—the weight slid off my chest the way chains do when someone cuts the lock they told you was protection.

The mountain was the same. The trees. The cabin. The road. I was not.

Part II

The mountain taught me two kinds of quiet. There’s the hush you fight—glaring, punitive, the kind that dares you to fill it with noise just to feel alive. And then there’s the quiet that holds you like a big hand on your back: breathe, son. I lived in the second one until the gravel announced trouble.

It was a Saturday. The kind of clear morning that makes pine needles smell like a bar of soap. The flat top at the diner had tightened my forearms and smoothed my mind, and I’d ridden back early with a brown bag of biscuits and the kind of bacon that reconsiders a man’s tongue. I poured coffee. I sat on the porch rail with my feet on the step like a boy at recess.

That’s when I heard them—tires grinding their teeth, not the easy roll of a neighbor easing through. Intent has a weight; their SUV carried it like a full trunk. They turned in hard, dust lifting like a theater curtain. Ray climbed out first, wearing his sheriff-in-his-head stance. Colt unfolded from the passenger seat, phone already clearing its throat.

“Morning,” I said, sipping. The coffee was too hot, bit my lip. I didn’t spit. Pain tells the truth; you don’t have to.

“Pack your things,” Ray said, hands on hips. “We’re taking you home.”

I leaned against the porch post and admired the part of the sky that didn’t care who we were. “Funny,” I said. “I thought I was home.”

He stepped closer, lowering his voice the way men do when they want to call control compassion. “Enough games, son. Madison’s worried sick. This stunt—” he gestured at the trees, at me “—has gone on long enough.”

Colt laughed under his breath and aimed the phone. “Season two,” he whispered like advertising to himself. “The Rescue Arc.”

“Put the phone away,” I said. Not loud. Not kind. The kind of flat a floor makes when you drop a wrench on it.

He froze. People freeze when reality doesn’t match their choreography. Then, cheeks pinking like a boy caught stealing gum, he slid the phone into his pocket. The crows in the nearest pine shuffled and muttered like critics.

“You’re not well,” Ray tried again. “Isolation does things to a man. We talked to someone in town—a social worker. Maybe a therapist. Folks want to help.”

I laughed, and it wasn’t mean. It was surprised. Imagine a man burning a house down and then offering you a glass of water. “Now I’m crazy because I didn’t break the way you wanted?” I said. “That’s rich.”

He opened his mouth. I went inside and returned with a leather folder, the edges warm from my hands, the paper inside crisp as pie crust. I’d asked Jules—the diner woman with the red bandana—to point me at a notary and the kind of lawyer who files clean, and she’d sent me to a storefront between the laundromat and a tax preparer that closes on Wednesdays. The woman there listened without blinking and slid forms across like a dealer. I signed my name until my hand remembered it.

I held the folder out to Ray like a man offering proof he doesn’t owe in a world that won’t take his word. “Statement of mental fitness,” I said. “Right to residency—tenancy established, utilities in my name. Proof of employment.” I tapped the diner letter on letterhead that smelled faintly of coffee. “You don’t get to spin this as a breakdown. Not today. Not to me. Not to a camera.”

He flipped through the pages. A vein in his temple wagged its finger. Control men don’t quit; they fray. Colt shifted from foot to foot, eyes flicking to the treeline like he might spot a better script hiding there.

“Listen,” Ray said finally, voice sanded down to the wood. “This isn’t what we wanted for you.”

“No,” I said, and looked him in the eyes long enough to watch something move behind them. “It’s what you wanted for yourselves. You wanted a story where you were the heroes who forged me in the wilderness. You wanted a laugh to pass around your table. You wanted to prove I was weak so you could rest easy believing you were strong. But I didn’t do the scene you wrote.” I tapped the folder. “I did this one.”

The silence that followed felt different than the mountain’s. This was the sound drywall makes when water has been wicking up from the baseboard for a long time and you finally touch a finger to it and it gives. He shoved the folder back, harder than necessary. “You’ll regret this,” he muttered, the way men do when their god fails.

“The only thing I regret,” I called after him as he turned, “is ever mistaking your approval for permission.”

The SUV spat gravel like curses and took the mountain downhill too hot. The dust took its time settling. I stood there and let it. My hands shook a little—adrenaline, not fear. A man can be steady and still note the tremor; knowing the difference is half of knowing himself.

They didn’t come back. But a thing like that doesn’t end with gravel and dust. The phone rang a week later. Not Ray. Not Colt. Madison.

Her voice was brittle, stretched thin over something hard. “Why are you doing this?” she said, not bothering with hello.

“Doing what?” I tucked the phone under my chin and wiped my hands on a rag because you should never let someone else’s panic stain your tools.

“Humiliating me,” she snapped. “People are talking.”

“Funny,” I said. “I thought that was your specialty.”

Silence like a dropped plate. Then, softer, the wound bleeding through: “It wasn’t supposed to go this way.”

“How was it supposed to go?” I asked, not unkind. Sometimes the most merciful thing you can do is ask the question someone has been answering with their life and never with their mouth.

“You were supposed to see yourself clearly,” she said. “You were supposed to… to get better.”

“Better than what?” I let the word turn in the air like a coin. “Better than not laughing when your brother points a camera at me? Better than not needing your father to declare me a man? Better than being quiet when the room requires cruelty before it passes the salt?”

She inhaled the way a person does when they realize they have been walking around with a borrowed spine. “We did it because you’re boring,” she said all at once, like ripping a bandage off a stubborn wound. “Embarrassing. You never speak up, you never take charge. Dad says—” She stopped. The way a car stops when the light switches from green to a kind of red that is not about traffic at all.

“Dad says I’m dead weight,” I finished for her. The knife sounded like a butter knife scraping toast. And here’s the thing about knives that dull: they leave grooves you can see long after the bread’s gone. “You don’t get to make a bonfire out of me because you forgot to build one of your own.”

“I love you,” she tried, and for a second the old muscle memory tugged—the part of me that wanted to fix, to soothe, to make it easy for everyone but myself. It’s a noble part if you use it right. It’s a leash if you don’t.

“Love doesn’t humiliate,” I said. “Love doesn’t conspire. Love doesn’t abandon a man in the woods and call it growth.”

The porch boards creaked under my boots as I paced. The cabin behind me breathed like an animal asleep. “I’m done,” I said. “Done being your project. Done being the punchline. Done shrinking so you can pretend your living room is big.”

“So that’s it?” she said. “You’re walking away?”

“No.” I looked at the line where trees meet sky and the sky doesn’t notice. “I’m walking back to myself. That happens to be in the opposite direction.”

The line died. Not a slam. Just the end of a cord I no longer needed to hold.

Six months is nothing in tree years. It’s a lifetime in a man’s. The diner turned into mornings stacked like plates—hot, honest, repeat. Word traveled faster than the crow with opinions that roosted in the east pine: the guy from the cabin could fix a hinge without cussing, frame a door so it didn’t sag, tile a bathroom floor without leaving a wobble underfoot. My phone started to ring for reasons that had nothing to do with apology. I said yes when I could, no when I should, and watched a line of jobs turn into a column of invoices and, eventually, a pile of cash no bank could misplace.

When the landlord of the diner decided the best use of a building was nostalgia and a sign that said Closed, Thanks for All the Memories, Jules slid me the key across the counter and said, “You want the bones?” The flat top felt like a friend whose back finally gave out. I ran my hand over the steel and said, “I’ll hang your coffee cup on the wall.” Then I ripped out the booths and built a shop. Tools on pegboard like a language. Workbenches at the right height. A radio that plays one station and doesn’t care to learn another. I hired two high school boys—Evan and Tino—who thought a miter saw was magic and listened like it might be contagious.

I sold the house in town—the one with my name on the mortgage but their laughter in the walls. I drove paperwork down the mountain and signed in rooms where pens are chained to counters as if the ink might run off and make a mess. The money, plus what I’d saved, bought me the cabin outright. The deed came in the mail like a birth certificate. I held it like a photograph of my grandfather’s hands.

Neighbors—real ones, not the kind who only knock when they need sugar—started showing up on Saturdays. We cut a new trail to the creek and built a small footbridge with a handrail that fit an old woman’s palm. We gathered under a string of lights the first night it was done and christened it with cans of beer and a pie Jules pretended she hadn’t baked because “it’s just flour and time, honey.” We named it the Not-So-Boring Bridge because Tino said if I was walking across it, the name ought to tell the truth.

Respect arrived like weather you notice only when it changes. It was the nod from Hank, the sawmill man, when I squared a board without checking twice. It was the extra cup of coffee sliding across the counter at the gas station because “I know you been swinging since sunup.” It was the way people began using my name in the same sentence as reliable and not flinching.

On the anniversary of the day they left me like a dog at the side of a highway, I lit a fire in the pit out back and texted the only list that mattered: neighbors, the boys, Jules, Hank and his wife, a couple who’d moved up from the city and learned to breathe with their mouths closed. “Bring meat if you like it. Bring nothing if you don’t. Chairs optional.”

We ate. We told stories that didn’t require a villain. The stars did what stars do—show up for free and humble everyone. About ten, my pocket buzzed. Unknown number.

I hope you’re happy, the text said.

I could have ignored it. I could have typed out a sermon and sent it on a digital road trip. Instead, I tilted the screen so the firelight glowed on it and typed two words.

I am.

The thing about truth is it doesn’t need context to sit up straight.

After midnight the coals were a red eye winking. The last chair scraped. The last bottle clinked into the recycling bag the way hope should—mundane, responsible, unglamorous. I sat in the rocker under a sky so busy with stars it looked like someone had spilled a jar of nails on black velvet. The cabin creaked once, considering its joints. I thought about the man I’d been—that polite ghost at a table that fed him laughter and called it dinner. I thought about the difference between patience and self-erasure. I thought about anger, and how the best thing it can be is fuel for a road that doesn’t circle back.

I should have slept like a man who’d finally put his tools down. Instead, I kept thinking about the title I’d give the story if I were the kind of man who posted online instead of living. We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny… That’s how Madison would sell it. That’s how Colt would cut it. That’s how Ray would nod through it, playing wise in the comments.

But here’s what nobody in their house would understand: I did return. Not to their driveway or their living room or their table set like a trap with place cards that say be small. I returned to a thing a man is supposed to be: the kind who can live inside his own skin without pausing to ask permission. That’s not funny. That’s plain.

A week later, an envelope arrived with the kind of legal breath a document uses when it knows it will change something. Petition. A box to check for abandonment. Another for mental cruelty, which would have made me laugh if I hadn’t already learned to save laughter for people who earn it.

I drove to the county seat in a truck that rattled the way old friends complain and parked under a maple that had been standing there long enough to watch men come and promise the same things under different haircuts. I filed my own papers—faults listed plainly, not because the court cares, but because my story does. I slid my wedding band into the little plastic envelope the clerk offered like a favor. She didn’t know she was asking for an artifact and a promise back.

On the way out of town, I stopped at the feed store for nails and at the dollar store for notepads because while everyone else argues big, life still wants a list. Back at the cabin, I laid the nails in a row like soldiers and the notepads in a stack like possibilities and breathed a long breath that reached my toes.

If Madison wanted to tell a version with caps—NOT FUNNY—she could have the comments. I had the bridge and the boys and a half-finished bookshelf for the family two ridges over who had more paperbacks than places to set them. I had the journal with the planting times and my own entries now about the day the creek rose and a covey of quail that likes the lower meadow and the fact that if you set a pie on the windowsill, raccoons will absolutely interview it for a job.

I had the mountain quiet that didn’t punish. I had the town noise that didn’t perform. And I had a folder in a drawer that said I didn’t owe anybody the version of me they laughed at. The one I owed was the one who swings the hammer straight.

I slept like a man who knows where his tools are. In the morning the light came in blunt and honest, the way I like it. The Honda ticked in the cool like a dog wagging a tail. The phone lay dark and obedient, a tool too, finally. I put on coffee, the good beans. The cup steamed. The day waited without tapping its foot.

I walked out onto the porch, looked at the spot where the SUVs once spat dust, and smiled a small, private smile a camera would never notice. I had work. I had bacon. I had a bridge that could hold the weight of a man and then another and then another, each surprised when the rail fit their hand.

That’s the day the joke died. Not with a punchline. With a life.

Part III — The Hearing, the Auction, and the Bridge That Held (≈1,750 words)

The petition came with neat boxes and big words, but the story it tried to tell was the same old one: I was the problem. Abandonment. Instability. Emotional cruelty. The digital filing had cost them a fee and some keystrokes. The real cost would be the parts of the truth they’d have to look at to make any of it stick.

Martin—my lawyer with an office between the laundromat and the tax place—pushed his glasses up his nose and read the petition twice like it might change on the second pass. “They’re tossing spaghetti,” he said finally. “Hope something clings.”

“Let ’em,” I said. “I’ve got a mop.”

He smiled the way men do when they’ve decided to like you because you don’t talk in circles. “We’ll counter with the obvious,” he said. “Documented abandonment. The video’s their own rope.” He tapped his pen on the page. “How attached are you to your house in town?”

“Not at all,” I said, and meant it. “You can carve ‘For Sale’ in the front door if it speeds things up.”

“Good,” he said. “Two things are true at once: you build clean, and they spend dirty. Keep it that way.”

The Dillon County courthouse is a box that’s seen better paint. A fan slices the air in the hallway like a lazy propeller. People go there to split themselves in two and discover which half they want to keep. The morning of the hearing, I wore clean jeans and a shirt with buttons, because respect doesn’t need a tie to stand up straight.

Madison arrived in heels that turned the tile into a metronome. Colt wore the look of a man who believed in the power of an audience but had somehow left his backstage pass at home. Ray held a folder like it could be used as a weapon. Elaine’s pearls looked like apologies you rent by the hour.

Judge Barrow read through the file with the purposeful boredom of a man who has seen every plot twist and still insists on reading the whole script. He looked up at me. “Mr. Harlan,” he said, “tell me—in your own words—how you ended up at a mountain cabin without a ride.”

I kept it short. “I agreed to a family trip. They agreed to go home with me. They left anyway.”

Barrow turned to Madison. “Mrs. Harlan?”

She tried on a laugh that didn’t fit her anymore. “It was a joke,” she said. “A… tradition. A nudge. We thought it might—”

“Temper the steel?” he finished, deadpan. The courtroom waited for laughter that didn’t arrive. “I’ve heard men use that line to excuse everything from fistfights to firings. It always sounds better to the person saying it than to the person bleeding.”

He flipped to a page. “This video,” he said, tapping a printed still of Colt’s smug phone-holding face, “makes it hard to argue surprise. You left him intentionally. You recorded his reaction. You intended an audience.”

Colt shifted, then did the thing men do when they’re out of rope. “He’s… boring,” he said to the ceiling tile. “He doesn’t… talk.”

Barrow set the paper down and blinked once. “Son,” he said, “boring doesn’t get you deserted in the woods.”

He turned to Ray. “And you, sir. You say you were worried later and consulted a social worker. That worry would have served you better one day earlier.”

Ray swallowed.

“Mr. Harlan,” Barrow said, “there’s a property issue tangled in here. Tell me how the cabin came into your name.”

“County auction,” I said. “An LLC owned the land. Taxes went unpaid. The county published notice like they do. I bid. No one from the family did.” I didn’t add: because Ray believed cheap victories last forever and taxes pay themselves if you smile wide enough.

Barrow glanced at the clerk, who nodded. “Record confirms the chain of title,” he said. “LLC dissolved. Property transferred. Deed recorded.”

Madison’s head snapped toward Ray so hard the pearls rattled. “You said—”

He didn’t look at her. Control men don’t share blame; they share looks that say later.

Barrow folded his hands. “Here’s what we are not going to do,” he said. “We are not going to pretend a man is less married because he is less noisy. We are not going to pretend ‘tradition’ is a magic word that blesses cruelty. We are not going to pretend a camera turns an insult into an intervention.”

He slid our proposed agreement back to the clerk. “Dissolution granted,” he said. “No support awarded. Each party keeps property titled in their name. Marital property already disposed of by mutual consent”—he nodded at Martin’s exhibits showing the house sale and the split of the proceeds—“remains disposed.” He looked at Madison, and for a moment his voice softened. “You want a husband who tells louder jokes. You married a man who sets quieter tables. Those are different men. I can’t conjure one from the other.”

Gavel. The sound is duller than in movies. It’s still a door closing.

Outside, the air bit. Madison stopped me on the steps, careful to stand where the light would fall on her like a filter. “You think you won,” she said. Not a question.

“I think I stopped losing,” I said.

“We gave you that cabin,” she snapped.

“No,” I said. “You gave me a long weekend I didn’t ask for. The county sold me a cabin you didn’t care enough to keep.”

That one landed. Her mouth worked. Then she said the thing that had been hovering behind her eyes since the hallway: “You were never enough.”

It didn’t gut me. It freed me, because it told the truth about her preference and my person, and those two things weren’t enemies anymore; they were simply not neighbors. “I’m enough for my own life,” I said. “Turns out that’s the only standard that holds.”

She turned the color a person turns when she isn’t the story anymore. “Someday,” she hissed, “you’ll wish you’d tried harder.”

“Someday,” I said, “you’ll wish you’d tried kinder.”

Colt filmed us from ten steps away, half-hidden behind a pillar, the way a boy hides behind a curtain and thinks he’s invisible because he can’t see his own feet. Ray stared at the horizon like it owed him a different county. Elaine twisted her pearls and looked small for the first time since I’d met her.

I walked to my truck. The seat held my weight like a friend.

The auction had been the strangest day of my year. It happened three months before the hearing in a room you’d use for a church potluck if you didn’t have a church. A county employee read parcel numbers into a microphone that squealed every third line. The LLC that owned the land had stopped paying taxes when the family started paying attention to things that shone and forgot the county requires checks, not charisma.

Jules sat in the back and pretended to fill out crossword puzzles while in fact running reconnaissance like a benevolent spy. Hank leaned in the doorway wearing a cap that said Hank’s Sawmill in white letters the sun had tried to bleach off and failed. Two men with clipboards did the nod math of people who flip houses for fun.

When our parcel came up, my heart did the little rabbit thing and then remembered it had swung an axe all winter and settled. Bidding started low enough to make me feel like I was stealing. The clipboards pushed once, then twice, then looked at me and looked at the room and remembered that cabins are charming until they need a roof and bowed out. I stood alone with my hand up at a number the judge would later call “mercifully affordable” and I would call “everything, but worth it.”

The county stamped the paper with ink that would outlast all of us. Three weeks later, a deed slipped into my mailbox like a secret that had decided to be public. I held it in both hands like a newborn.

“You could’ve told them,” Jules said, meaning Madison’s family.

“They could’ve read the notice,” I said, meaning the paper in the county foyer under the clock where news lives when nobody wants to claim it.

“You keep making sense,” she said. “It’s bad for the ratings.”

The bridge became a joke among us because we needed a name and weren’t sentimental enough to call it Friendship without gagging. So we called it what we’d called it the night we christened it with beer: the Not-So-Boring Bridge. It’s two planks wide with a rail that fits an old hand and a young one. It doesn’t bounce. When you step on it, the creek keeps talking and doesn’t ask you to answer. That’s all a bridge owes anyone.

Evan and Tino hammered with the focused incompetence of boys learning to become men who will not drop a nail and call it fate. I showed them how to measure from the same end twice because a board doesn’t care about your hopes. I showed them how to cut proud and sand back. I showed them how to throw their shoulders away from the saw because you only get one set of hands.

“Why’s it called Not-So-Boring?” Tino asked, squinting down the rail he’d planed. The light caught the curl of wood like a ribbon lifting.

“Because I walk on it,” I said.

He snorted. “You really think you’re boring?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “Like on purpose.”

He made a face that said he was turning that phrase over and trying to decide if any of his friends would ever understand it. “You don’t talk much,” he said. “But you don’t feel… gone.”

“That’s the trick,” I said. “Say less. Mean more.”

He smirked. “You should put that on a T-shirt.”

“Build it into a bridge,” I said. “People will feel it with their feet.”

The last paper to sign was the one that felt the least like an ending and most like permission. Martin slid it across the desk without ceremony. “Final decree,” he said. “The state says so, but you already lived it.”

I signed. He notarized. The stamp thumped. We shook hands like men who know where to put their gratitude.

On the way home, the mountain smelled like hot pine and dust. The Honda rode strapped in the bed of the truck because I’d bought a load of cedar and wasn’t ready to ask it to share space with lumber. When I rounded the last bend, the cabin sat where I’d left it, which sounds simple until you’ve lived a life where people move your chairs when you’re not looking.

I set the cedar planks beside the shop and ran a hand over their ends. “We’re going to be bookshelves,” I said out loud like a fool and a priest. The wind took the blessing and didn’t argue.

My phone buzzed one last time that day. A text from a number I didn’t have saved. Not Colt. Not Madison. Not Ray. The message was a single sentence that contained too much to be short and yet somehow fit in one line: I heard you kept it.

I stared for a second too long. Then my thumbs did the simple work that felt like putting a small stone where it belonged on a grave.

I kept myself.

There was a party a week later, not because the decree needed confetti but because the cedar needed cutting and I’ve learned that men work better with a sandwich at noon and laughter that doesn’t require victims. We grilled meat on a rig Hank insisted was legal because he’d welded it himself and the law respects ingenuity if you don’t invite the sheriff. Jules brought a peach cobbler that would make you forget every pie you’ve ever badmouthed. Evan and Tino argued about music and then shut up when the tall woman with the ranger badge and the braid down her back put on a playlist that made everybody nod.

Her name was Mara. She’d come up to look at the slope after spring runoff and stayed to hold a board while we screwed it down and then to drink a beer and then to lean on the porch rail when the light did its gold thing across the pines and say, “You ever think about a fire break along that north edge?” in a tone that said this is your land and your call.

“Show me,” I said. She did, tracing the invisible line with her hand like she was sketching a blessing.

That night when the last chair clacked, I sat in the rocker with the deed in a drawer and the bridge at my back and the sound of a creek that didn’t need me to answer. Somewhere out there, a man was telling a story that painted me as a punchline. Somewhere else, a woman was turning pearls in a kitchen where regret tasted like dish soap. The county held a piece of paper with my name on a line that meant I owed property tax and nothing else.

The thing about the joke dying is this: the room gets quiet after. Not empty. Quiet. That’s when you hear the things that matter.

I slept. The mountain held. The Honda ticked as it cooled. The next morning, work waited without tapping its foot. I told it I was ready.

To be continued…

Part IV

The first scent of smoke that summer arrived like a memory. Not bonfire. Not bacon. Dry, old, far. A wind from the north carried it thin across the ridge and set the crows to complaining, which is how I knew to listen harder.

Mara came up the drive in her state rig at noon, dust painting her bumper. She didn’t waste my time or hers. “Lightning strike north of Timber Ridge,” she said, pulling a paper map from the glove box out of habit, even though her phone could do tricks I still didn’t trust. “Ground fire. Low and slow—for now. If the wind swings east we’ll smell it only. If it swings south, you’ll see it.”

“What do you need?” I asked.

She smiled like a person who hadn’t had to answer that question many times without hidden prices attached. “Clear brush along your north line. I’ve got a crew on the ridge cut, but it’s patchy. If it turns, you’ll have embers and attitude.”

“Boys!” I yelled. Evan and Tino abandoned their argument about whether music with words was actually music and came trotting like eager dogs. “Rakes. Saws. North line.”

We cut for three hours. Dry pine needles hiss when you rake them into compliance. Sweat found its way down our backs and made little burns where old splinters lived. Mara worked with us, not above us, which is how you know somebody wears a badge for purpose, not personality.

By late afternoon the air turned the color of old coins. Smoke pressed down on the ridges like a hand learning the mountain’s face. It stayed out there—menacing, not immediate. We drank long from the hose and didn’t care that it tasted like rubber and county pipes.

Around dusk my phone buzzed. Reception doesn’t care about your opinion. It cares about weather and whim. A text from an unknown number popped in. Evac notice up the road. Any room? The number signed itself: Hanks.

“Bring whoever,” I typed, and before I could hit send, I added, and whatever you love that doesn’t plug in.

They came like a parade of sensible cars. Hank’s truck with a trailer that clanked. His wife with a cat in a carrier that looked like it held a temper. The new couple from two ridges over with their toddler and a suitcase that had seen airports and would now see pines. A woman I knew only as Mrs. Ortega from church-in-the-park Sundays, carrying a framed photo of a man in uniform like a relic.

Jules arrived last with a cooler and a look that said: I will manage you if you need managing and leave you alone if you don’t. “Feed line is shut off up near mile six,” she said, unloading casseroles like a food truck. “They’re keeping roads open for engines. We’ll be here a night, maybe two.”

We didn’t panic. We planned. Tents on the meadow. Cots in the shop. The Not-So-Boring Bridge suddenly mattered more than its name. It offered a path to the creek if we needed water in a hurry, a way to move people without wading, a place to gather if we had to point and count.

At midnight the wind turned its head south and exhaled. The smoke thickened in the tree line and then let go, dragging a low curtain across our faces. I walked the line with a headlamp. Embers can ride a mile on a breeze like little evil birds and decide to nest in your gutter.

That’s why I saw them—headlights crawling up my drive slow, cautious. The SUV idled as if asking permission from the night. I stepped into the beam and raised a hand. The engine cut. The door opened.

Madison got out first. Jeans. A hoodie. Hair not done, face not done. The panic had stripped her to person. Ray climbed out the other side, one hand on a bag like he’d been told to pack by someone who knows how to pack a life in a hurry. Elaine followed, clutching a shoebox. Colt brought up the rear, eyes wide the way boys’ eyes get when the world has stopped clapping on cue.

“We got the alert,” Madison said, voice small. “They said head south or find a place to shelter. I—” She stopped. The sentence couldn’t carry its middle.

“You can stay,” I said. If surprise flickered on her face, it didn’t land long. Fire makes some choices for you.

“Thank you,” Elaine whispered, and put her hand on my arm in a way that didn’t ask me to forgive anything but did ask me to be decent. I let the question stand and answered it with a nod.

We found them places. Not in the house—they didn’t ask, and I didn’t offer. Cots in the shop with everyone else, because everyone else is how you get through nights that smell like matches. Jules pressed bowls into their hands. Mr. Ortega’s widow sat with Elaine and asked about the shoebox, and Elaine showed her—letters, yellowed, tied with string. “My mother’s courtship,” she said, smiling at something that had nothing to do with county lines or videos or judges. For a second the woman she had been—a girl, hopeful—stood in the room and then sat back down in time.

Colt looked at the bridge like it might critique him. “You built that?” he asked.

“With help,” I said. “You want to walk it or make a video?”

He winced. That was new. “Just walk,” he said.

We walked to the creek. Stars were a rumor behind the smoke. The bridge didn’t bounce. He put a hand on the rail and squeezed as if to test whether wood tells lies. “You really bought this place?” he asked, voice small enough to qualify as honest.

“No,” I said. “I bought a deed. Then I kept the place.”

He nodded like he’d touched a sentence he didn’t have the words to read. “I was a jerk,” he said without looking at me.

“Yep,” I said. Forgiveness that arrives too fast is just another performance.

He took air into his lungs and tried again. “I thought the only way to be seen was to be loud. But the loudest thing I ever did was stupid.”

“That’s how you learn,” I said. “If you’re lucky.”

He nodded. “I’d like to be.”

We stood there and listened to the creek talk about gravity and patience. Sometimes that’s all you can do for a boy who’s figured out the difference between laugh-track and life: stand beside him while he learns how to hear.

By dawn the wind lay down. The fire turned its face away like a sulking child. The all-clear rolled through the county phones in a wave of tones that sounded like a choir. People begin a day after a night like that with two kinds of relief: one for what didn’t happen, one for what they learned they could do.

The camp broke easy. Hugs at cars. Sandwiches wrapped in foil like I love yous you can eat later. Hank thumped my back and left a bag of nails as thanks because men like us speak fluent hardware. Mrs. Ortega kissed the air near my cheek and said, “You’ve got a good table,” meaning the life, not the lumber.

Madison’s family lingered. Ray came to me last, hat in hand, humility like a new suit not yet tailored. “I said things,” he began, and I put up a hand.

“So did I,” I said. “Some were true. Some were scared. Let’s keep the true ones and feed the scared ones to the fire.”

He blinked. Then he did something I had not expected and will not forget: he shook my hand not like a test, not like a show, but like a man who had finally discovered the use of the gesture. “You built that bridge,” he said, glancing toward the creek. “We walked it.”

“Then let it do its job,” I said.

After they left, the mountain exhaled. The cabin settled. I lay down for an hour that felt like a full night and dreamed nothing, which is a kind of mercy.

The video came out the next week. Not by Colt. He’d retired from that. By a woman from town who runs the library Instagram with a ruthlessness I admire. It was thirty seconds of still images—the bridge, the shop, the line of cots—and a caption that said: Neighbors took care of neighbors. That’s the whole story. (Also, our fire break looks good, thanks to many.)

Madison texted me the link. I’m glad you were there, she wrote.

So am I, I answered.

A day later, a final envelope arrived from the court. Not a surprise. Just the last stone in the wall. Name change for Madison back to her maiden. I put the envelope in the drawer with the deed and the journal. Paper and paper and paper. They don’t love you back, but they don’t lie either.

Mara came by on a Tuesday with a bag of bagels and a topo map. “You know,” she said, tracing lines with her finger, “this old spur road would make a good trail if you cut the deadfall. People could walk without tearing up the slope. Put a bench halfway where the view hits you in the chest.”

“Bench,” I said, tasting the word. “We can do a bench.”

“Name it something ridiculous,” she said. “People behave better at places that don’t take themselves too seriously.”

“The Still-Here Seat,” I said.

She smiled. “That one’s free.”

We cut the trail in two weekends. The boys learned to stack brush so rabbits could hide and fire would think twice. We hauled up a slab of cedar and planed it in place. Hank burned the name into the back with a branding iron he’d made for his cattle. It read like a promise someone had kept a long time ago and decided to keep again.

On the day we opened it to no one in particular, I sat on the bench with a beer and looked at the ridge where smoke had almost chosen us. The seat didn’t make a speech. It didn’t need to. Two hikers came by accident, sat, took off their hats, and didn’t talk for five minutes. That’s better than applause. That’s respect learning how to sit quietly.

Madison hiked up near dusk. Alone. She stood at the edge of the clearing like someone approaching a church she isn’t sure she’s allowed inside. “Can I?” she asked.

“It’s a bench,” I said. “It doesn’t check IDs.”

We sat. The view did the thing it does: made you feel small in the way that makes room for better things to be big. After a while she said, “We’re moving.”

“Where?”

“South. By the coast. Dad says the air will do him good.” She looked down at her hands. No ring now. “I wanted to say… thank you. For that night.”

“You were neighbors,” I said. “That’s the job.”

She nodded. “I’ve been writing down what I do to hurt people,” she said, and I hid my surprise because that’s a sentence I would’ve bet against ever hearing. “It’s a long list. I’m trying to stop adding to it.”

“That’s a good list,” I said. “Add this: forgive yourself for the things you didn’t know yet.”

She laughed once, not unkindly. “You got that from the journal, didn’t you?”

“Something like that.”

She stood. “I’m sorry,” she said. “For the video. For the cabin. For making you small to sell myself big.” She swallowed. “You weren’t boring. You were steady. I couldn’t tell the difference.”

“I couldn’t either,” I said. “Until I learned to be one on purpose.”

She nodded. “Goodbye, then.”

“Goodbye, Mads,” I said, and meant it without knives.

She walked back down the trail. The brush I’d stacked gave a rabbit a place to pause. The bench held my weight and did not complain.

The ending wasn’t fireworks. It was a door left unlocked because you trust the night. It was a porch light you switch on for yourself because the world’s dark is ordinary, not out to get you. It was a dog that wandered into my shop one morning smelling like creek and stubborn and decided he worked for me now. I named him Biscuit because he showed up at noon and made himself at home like a man with an employee discount.

It was a note from the county that said, “Thank you for the fire break. See you next season.” It was a magnet on my fridge with a list that never empties: sharpen blades, oil the hinge, call Mrs. Ortega about the step, check on the couple with the toddler, buy more screws, don’t forget coffee filters because paper towels make the pot angry.

It was Mara on the porch some evenings with a can of something cold and sensible stories about people who get lost and the ones who find them. It was the boys arguing about music and then learning a waltz rhythm to set their hammer blows because timing is timing whether it’s a radio or a nail.

It was the Not-So-Boring Bridge doing exactly what it was built to do, carrying feet over water without ceremony. It was the Still-Here Seat holding strangers and letting them feel like they’d had an idea.

If you ask Madison about it now, she’ll tell it in a way that plays better at brunch. If you ask Ray, he’ll say a man he misjudged opened a gate on a bad night and then built a bench with his name burned on the back. If you ask Colt, he’ll look at his shoes and say he doesn’t film men who are building.

If you ask me, I’ll tell you the story the way I’ve been telling everything since the mountain taught me the right kind of quiet: simple, straight, with enough nails to hold and enough room to breathe.

They left me miles away from home as a joke.

I came back. Not to them.

To me.

And when I returned, it wasn’t funny.

It was final. And it stayed.

THE END

News

Sister Announced She Was Pregnant With My Husband’s Baby at My Birthday—She Didn’t Know About the Prenup CH2

Part I The florist had crammed the hotel ballroom with white roses because “thirty deserves a thousand blooms,” according to…

I Found My Parents Locked Out With Blue Lips While My In-Laws Partied Inside…So I Made Them Pay CH2

Part I — When Help Knocks and the Locks Change Robert said it like he was reporting the weather. “My…

Parents Chose a Vegas Poker Party Over My Surgery — My 3 Kids Left Alone, and I Finally Cut Them Off CH2

Part I: The Line in the Doorframe I told the bank we were done. That was the sentence that cut…

WRONGFULLY JAILED FOR 2 YEARS – NOW I’M FREE, BUT EVERYTHING I BUILT IS GONE CH2

Part One: The Strip-Mall Law Two years of my life were stolen because I was walking home from school. That’s…

Black Nurse Insulted by Doctor, Turns Out She’s the Chief of Surgery CH2

Part One: Night Shift The night shift in the emergency department had a sound all its own—a layered hum of…

I Joked That Even His Best Friend Tried Me—He Overheard And Filed For Divorce Fast CH2

Part One: The Sound of My Own Laughter The night I said it, the line came out slick and glinting,…

End of content

No more pages to load