Part I: Night Shift

The silence in Room 1219 wasn’t really silence. It was a quilt of soft, mechanical assurances—steady beeps from a cardiac monitor, the whisper-sigh of the ventilator like someone sleeping on purpose, the gentle burble of IV fluid as it counted out time in drops. In the dark glass of the window, the lights of Saint Mary’s Hospital floated like distant ships, and beyond them the city hummed at a polite distance, as if the whole world were trying not to wake the girl in the bed.

“Evening, Miss Montgomery,” Marcus Williams whispered, easing his cleaning cart through the door and letting it settle in the corner the way a father settles a sleeping child. “It’s just me.”

He said it every time he came, and every time the words landed in the same place inside his throat—a ritual, like the cross some people make, or the way he always kissed his fingers and touched the photograph of his daughter taped inside the cart lid. Amy at seven, front teeth gapped, hair escaping from its braids, a sticker from the respiratory clinic proudly stuck to her sweater: You did a great job breathing.

Six months. That’s how long Elena Montgomery had been here. Six months of nurses with voices pitched low and certain. Six months of doctors wearing their names like armor: Johns Hopkins. Mayo Clinic. Harvard. Specialists who could point to every ridge and river of a brain and still have to say, gently, we don’t know.

Six months of billionaire heiress turned question mark.

Marcus rolled the microfiber mop into the corner by the window and paused to listen. You learned to hear the hospital if you stayed long enough. Not just its alarms and pages, but its moods—the way the surgical floor brightened its voice in the morning; the way pediatrics sang to itself after dinner. The ICU held its breath. And neurology, where Miss Montgomery lay, had a habit of sounding like it was thinking.

He took in the room like he always did—bed, monitors, the sterile artistry of tubing. Fresh bouquet on the side table, cream roses with a hand-lettered card: We miss you at the office. Photographs propped beneath it: Elena in a black suit, chin up in a way that said she enjoyed winning; Elena laughing in a candid that had probably cost a magazine a small fortune; Elena between two men in tuxedos, one of whom belonged to her father, the other to the Forbes list.

Her eyes now looked at nothing. Not rolled back, not frantic under lid. Just open and vacant, like their owner had stepped into another room and left them behind to hold her place.

“Gonna be quick,” Marcus told her, because he always told her the plan. “And I won’t move your plant, because I know you like the sun on it.”

He worked the room in his steady pattern—disinfect high-touch first, light sweep, wipe surfaces, mop last—hands moving with the practiced grace of a man who has learned to trust his routines because so many other things in his life refused to hold still. He’d taken the night shift the year Amy started using inhalers more often than crayons, after Sarah died and grief became a second job. Night shifts paid better. Night shifts made morning school drop-offs possible if he slept fast. Night shifts were how you kept a child’s lungs open and the rent paid.

When he finished, he nudged the cart to the window to lift the blind an inch. He liked the way dawn sneaked up on the hospital, softening it. His elbow knocked the ceramic pot of the little snake plant on the sill. It toppled and hit the floor with a small, damp thud; the kind of sound that draws no attention in a city, but in a quiet room becomes a thunderclap in miniature.

Elena’s head moved.

Not much. Not the hard jerk of a startle. Just a fraction, a tilt toward the sound that could have been accident, could have been nothing at all.

Marcus froze, breath perched precariously in his throat. He looked at her face. The eyes—still unfocused—hung a beat to the right, near the window. He felt something too old to call hope and too young to call reason scrape against the cage of his ribs.

“Sorry,” he whispered, crouching to right the plant. “My bad.”

He stayed down there, heartbeat in his ears, and let his rag slide to the tile. It landed with a quiet splat on the other side of the bed.

Elena’s eyes slid left.

He stood so fast his knee popped. He was alone with a girl worth more than a small country and suddenly felt like a boy in a church, afraid to move.

“Okay,” he whispered, because occupants always did better when you gave them an okay to hold onto. He walked around the bed to the chair and pulled it a few inches. The feet whispered against the floor. Her gaze tracked, barely, like a compass needle yawing a degree.

He did it again. Drop. Scrape. Shift. The tiny ballet of sound and the subtle choreography of her eyes began to align like two stars finally finding each other.

Marcus set his palms on the rail and lowered his head until he was level with her. Up close, she didn’t look like a headline or a magazine cover or a press release. She looked like someone who had been listening to a language everyone else forgot to speak.

“I see you,” he said, voice rough. “You hear me?” Her eyes didn’t flicker at the words, but when he drummed his fingertips softly against the rail—absent-minded as a man waiting on hold—her head came a breath toward the rhythm.

In training, they teach you not to overstep. Scope of duty. Hierarchy. Don’t lose your job trying to be a doctor if you are the man with the mop. But sometimes life fails to arrange itself neatly within policy.

Marcus pushed his cart out into the hall and tracked the name badge of the passing neurologist he saw most mornings. Chen, Rebecca M., MD. She moved like she had a backpack full of patients and a clock running on every one of them. He touched her sleeve the way you touch something fragile.

“Excuse me, Doctor,” he said. “I think I noticed something about Miss Montgomery.”

Her first reaction was the one the white coat teaches you to have without even trying: a polite nod to the layperson coupled with a pivot toward the chart. “Mr. Williams, I appreciate your—”

“She responds to sound,” he said, quietly, because quiet is what gets heard in hospitals. “Not talking. Things.” He gestured. “Dropped rag. Chair feet. Her eyes go to it. Her head.”

That stopped her. Not because the claim was extravagant, but because his tone had no theater in it. He wasn’t here for a story. He was here for the small truth in it.

“Show me,” she said.

Back in the room, Dr. Chen folded her arms, skeptical and open at once. Marcus performed the clumsy miracle—plant, rag, chair. Then he added a new one: the blinds. He raised them a sliver. The plastic slats gave a small clack-clack. Elena’s eye-line swiveled, not much. Enough.

Dr. Chen leaned in. Her shoulders relaxed in a way that looked like somebody loosening a belt. “My god,” she murmured. “We haven’t been testing for this. We’ve been telling her what to do instead of asking her what she can hear.”

Outside, the corridor breathed. People walked by unaware that the floor plan of a life might be redrawing itself behind the door.

“I’ll order auditory mapping,” Dr. Chen said, already half out the door to find someone with electrodes and a portable EEG. She looked back at Marcus and surprised him with the directness in her gaze. “Good catch.”

He looked at Elena. “She caught it,” he said. “I just listened.”

By noon, the room had become a tented city of equipment. A young audiologist with a nose ring and a careful voice explained the tests to Elena as if she could answer, and then to Marcus as if he might need to, and then to Dr. Chen because doctors like to hear the things they ordered putting on their coats of meaning.

Auditory stimuli. Evoked potentials. The hearing pathways were fine; in fact, Elena’s responses to environmental noise were sharper than average. But when the audiologist tried to layer human speech on top, the responses attenuated like radio static under weather.

“She’s not processing voices in the usual pathway,” Dr. Chen said, half to herself, as she watched the live graph twitch and settle. “But incidental sounds? They get through. And she can orient to them. We need to see whether she can choose.”

They set up a simple grid—four speakers in the room corners, four tones of slightly different pitch. The audiologist pinged them in random patterns while Dr. Chen watched Elena’s gaze. Right. Left. Down. Up. It wasn’t perfect. The latency was maddening. But a pattern emerged—the eyes were not just flicking. They were following.

Somebody murmured “locked-in,” and the air changed. That phrase had been floating around the edges of her case for months, but no MRI, no bloodwork, no reflex exam had cared to confirm it. Locked-in was the thing that haunted the residents—the mind you could not reach behind a face the brain had forgotten to animate.

“Not classic,” Dr. Chen corrected, fingers flying over her tablet. “Atypical. Maybe triggered by—what were her supplements?”

A nurse clicked into the chart. “Chronic fatigue—stack of nutraceuticals.”

“Bring me the list.” Dr. Chen’s voice was calm, but her eyes glinted the way they do when a trail you’ve been on for months finally throws off a thread of light. “And page tox.”

Marcus stepped back toward the window, to where his cart sat like a friend waiting. He let his fingers rest for a second on the smudged handle and thought of Amy asleep in the car seat on nights he’d parked under the ER canopy to run in a janitor application while Sarah’s cough hacked holes in the future in the passenger seat. He thought of Mrs. Chen down the hall with the neat stack of unread mail he’d broken down for recycling after she admitted her glasses weren’t cutting it. He thought of Elena’s eyes—vacant until they weren’t, a shape in a fog coming toward shore.

The door opened again and a man stepped in wearing a suit that looked like a yes. His face had the careful over-smoothness of skin cultivated by expensive creams and the deeply lined mouth of someone who had been saying do whatever it takes for half a year. His hair was the kind that looks normal on magazine covers and ridiculous in parking lots. He wasn’t ridiculous. He was terrified.

“Mr. Montgomery,” Dr. Chen said, straightening, offering a hand. “I’m Dr. Chen. We think we may be making some progress.”

He took her hand, looked at Elena, and nodded in a way that tried to be gracious under the weight of grief. Then he saw Marcus in the corner and did a double take—the kind you see when a person realizes they have been watched by the sort of person they are trained not to see.

“Are you—the one who noticed?” he said.

Marcus cleared his throat. He had never spoken to a billionaire before—even the word felt silly in his mouth, too big and shiny to fit. “Just noticed she turned her head when something fell,” he said. “That’s all.”

“That’s not all,” Dr. Chen said, quick as a correction can be gentle. “It may be the difference between months of nothing and starting now.”

Mr. Montgomery’s eyes did a strange thing: they filled but did not fall. He looked at his daughter and then at the man with the mop and then at the doctor and something like humility, not so different from panic if you squint, crossed his face. “Thank you,” he said, and his voice was the rough of a road. “I have said that sentence to a hundred doctors while meaning less than I mean it now.”

Marcus looked down at his shoes, which desperately needed polish he could not afford. “You’re welcome,” he said. “I’m sorry for knocking over her plant.”

The slightest hitch in the air told him he’d said something odd in a room where odd things were usually expensive tests. Dr. Chen smiled with only half her mouth. “Sometimes accidents open doors,” she said. “Mr. Montgomery, may we have permission to trial an auditory-evoked protocol? And to consult toxicology regarding a possible supplement-induced syndrome?”

“Whatever it takes,” he said, because sometimes you say the thing your mouth knows is true before your checkbook gets its say. “Whatever she needs. Whatever you need.”

They got to work.

For three hours, the room was a study in chosen sound. Dr. Chen orchestrated like a conductor who’d grown sentimental about hearing the world come back to life. Tonal patterns. Environmental noises cataloged like museum pieces—a chair scrape, a glass chime, a hand on a rail. Elena’s eyes learned and relearned their own circuitry. When Dr. Chen told her, “Follow the bell,” and the audiologist held the bell and did nothing, Elena’s eyes did nothing. When the bell rang from the left, the eyes slid left. The tiniest flutter at the corner of her mouth—a muscle Dr. Chen later showed the team on a slow-motion video, rewound and replayed as if it were a moon landing—began to show up when a task was completed.

“It’s not random,” Dr. Chen said, face flushed with the joy of someone allowed to replace a theory with a patient. “It’s preference. She’s saying yes like that.”

“Like how?” Mr. Montgomery asked, eyes on his daughter like a drowning man on a board.

Dr. Chen pointed to the corner of Elena’s right eye. “That flutter,” she said. “We’re going to make a map out of that.”

Toxicology arrived with a stack of literature and a lugubrious fellow who looked like he had been born with nouns like beta-adrenergic in his mouth. He listened, nodding, streamlined the supplement list, and then perked at two in combination—one a “natural energy booster” with dubious sourcing, the other a high-dose nootropic that had been making the rounds in the tech circles that talked loudly about focus and quietly about consequences.

“In rare cases,” he said, tapping a paper, “this concoction creates a neuromodulatory interference—locks executive response pathways while sparing perceptual input. It presents like an atypical locked-in. It is… unusual.”

Dr. Chen’s eyes flicked to Elena and back. “Can it be reversed?”

“Slowly,” he said. “Carefully. With a taper, with adjunct neurorehabilitation. It won’t be elegant.”

“I don’t care about elegant,” Mr. Montgomery said. “I care about her walking out of here.”

“Then we proceed,” Dr. Chen said, and in her voice was the relief of a person finally allowed to move.

“Should I go?” Marcus asked, a hand already on the cart.

Dr. Chen surprised him again. “Stay,” she said. “If you can. She responds to you. Left. Right. Plant. Rag. Chair. We’ll need all the cues we can get.”

Marcus nodded. He thought of Amy’s inhaler and the way her chest sometimes lifted like a fish trying to remember how air works. He thought of the pharmacy hours. He thought of the subway schedule. He thought of the way Elena’s eyes had found his plant on the floor and then, a beat later, his face. He texted his neighbor—Mrs. Chen, not the doctor—to make sure Amy got from her after-school program to the apartment, to pull the frozen lasagna from the freezer. He promised himself he would not become a hero. Heroes don’t make it to breakfast.

He stayed.

They worked until evening disguised itself as afternoon again. At seven, the room breathed with the ghost of a rhythm—the smallest yes, the smallest no. At eight, Elena went still as a screen saver. Dr. Chen declared a halt. Progress was a muscle you could fatigue.

In the hallway, Dr. Chen closed her hand around Marcus’s in a handshake that didn’t make him feel like her equal, but did make him feel like a necessary fact. “Shift over?” she asked.

“In ten,” he said. “I’ll finish my floor.”

“You did a good thing,” she said, and there was no performance in it.

He shrugged. “I just noticed,” he said. “Sometimes that’s all.”

He wheeled his cart away, and for the first time in months, Room 1219 felt less like a tomb and more like a stage being set for something that might yet happen.

By the time Marcus clocked out and stepped into the chill of the hospital’s night, the sky had flattened into the kind of tired blue that makes a man think of hot showers and warm children. He called Amy, who wanted to tell him about a science experiment with baking soda and vinegar and a small eruption she swore had touched the ceiling. He laughed and told her he loved her, and when he hung up, he sat on the low wall by the ambulance bay a minute longer than usual and listened.

Somewhere on the twelfth floor, a nurse laughed. A baby cried in the ER. A siren dopplered past and away. He thought of Elena’s eyes tracking a rag hitting the floor and felt a thousand small things shift—treacherous hope and ordinary fatigue and a bright thread of certainty that caring was not for the credentialed alone.

Behind him, the automatic doors sighed open and closed, letting out a ribbon of warm, antiseptic air.

“Mr. Williams?”

He turned. The man in the expensive suit was there again, tie loosened, the kind of look on his face that made Marcus stand without thinking, as if decorum were a way to keep a man from falling apart.

“Sir,” Marcus said.

“I don’t know how to thank you,” Mr. Montgomery said, voice thick and clumsy around its own earnestness. “My daughter is my life. Since her mother died… I didn’t realize how much the world had felt like it was closing until just now, when Dr. Chen said there was a way out.”

“Doctors said that,” Marcus said quietly. “I just… paid attention.”

“Exactly,” Mr. Montgomery said, like he’d been waiting for those words to find his mouth. “You did. And I want to… we want to… show our gratitude.”

Marcus felt the reflexive no forming—politeness, pride, the need to claim his observation as simply what people do when they are trying to be decent in a world that makes decency feel like an act. He thought of the mason jar on his kitchen counter labeled College with coins making a low clink each time Amy gleefully dropped one in. He thought of Amy scribbling a white coat on a stick-figure drawing of herself, telling him she would be a lung doctor “so kids could be better at air.”

“Sir,” he said, choosing each word like it mattered. “I didn’t do it for a reward. She’s going to get better. That’s enough.” He hesitated, then added, “But if you want to help… my daughter wants to help sick people when she grows up. If you really want to do something, help her get there.”

Mr. Montgomery’s eyes spilled over in a quiet he did not bother to polish away. “Name it,” he said.

Marcus did not name a number. He named a future. And somewhere on the twelfth floor, a young woman in a quiet room registered a soft sound from a hallway and turned her eyes toward it like a person who had decided, against all odds, to come back.

Part II:

Elena Montgomery’s case became the pulse of Saint Mary’s.

The day after Marcus showed Dr. Chen the rag and the plant trick, the neurology wing filled with a new kind of energy. Specialists who had already flown in, made their pronouncements, and flown back out were now requesting video feeds of the sessions. Nurses who had previously moved in and out of Room 1219 with the reverent indifference of routine began lingering at her bedside, whispering encouragement as if the girl behind those vacant eyes might catch hold of the sound and pull herself up by it.

And in the middle of it all was Marcus, the janitor with the mop, who suddenly found himself being consulted like he was part of the team.

Dr. Chen wasted no time. “If she can track, we can build,” she told the team.

They began with the basics. Four distinct sounds: a bell, a woodblock, a clicker, and a small hand drum.

“Bell means yes,” Dr. Chen explained. “Clicker means no. Woodblock means stop. Drum means repeat.”

The audiologist pinged each sound in randomized order, while Marcus stood off to the side, watching Elena’s eyes. The subtle flutter at the corner of her right eye confirmed what his gut had known since that first night with the plant: she wasn’t gone. She was waiting.

Within a week, they had established a rudimentary communication system. The bell rang, her eyes fluttered. The clicker tapped, and she deliberately turned her gaze away. Stop. Repeat. Yes. No. The world was opening.

“Most locked-in patients need months to reach this point,” Dr. Chen murmured one night, her exhaustion battling with awe. “She’s moving faster than expected.”

Marcus only nodded. He knew something they didn’t: Elena had been practicing with him for weeks before anyone else believed it.

It didn’t take long for word to spread.

Nurses in the cafeteria whispered about how “the janitor cracked the case.” Orderlies slapped him on the back. Some of the younger residents eyed him with thinly veiled jealousy, while the older doctors gave him the polite nod of inclusion, the kind you give to someone you don’t quite know how to categorize.

“You must feel like a hero,” one respiratory therapist said.

Marcus shook his head. “Heroes are the ones keeping her alive. I just listened.”

But deep down, he knew it was more than that. Listening was something most people didn’t do. Not really.

Three days later, Jonathan Montgomery returned. This time, he wasn’t in a tailored suit but in a cardigan that looked older than his fortune. His face was drawn, but his eyes carried the light of hope, and when he looked at Marcus, it was with a gratitude so raw it was almost uncomfortable.

“Mr. Williams,” he said softly. “You saved my daughter.”

Marcus shook his head. “The doctors saved her, sir. I just… noticed.”

Jonathan stepped closer, his voice thick with emotion. “When the best minds in the world told me to prepare for the worst, you saw what they didn’t. How do I repay that?”

Marcus thought of Amy. Her mason jar of coins. Her wide eyes whenever she walked past the children’s wing and said, I’m going to wear one of those coats someday, Daddy.

“You don’t owe me anything,” Marcus said. Then, after a pause: “But if you really want to help… help Amy get there.”

Jonathan blinked. “Amy?”

“My daughter,” Marcus explained. “She wants to be a doctor. She’s only seven, but she already knows more about inhalers than most grown-ups.”

Jonathan smiled, the first genuine smile Marcus had seen on him. “Then that’s what we’ll do.”

The Montgomery family moved mountains with their money, but they didn’t forget the man with the mop. A week later, Jonathan called Marcus into a quiet office near the neurology wing.

“I’ve spoken with the board of our family foundation,” he said. “We’re establishing the Amy Williams Scholarship Fund. Full tuition support for her education—from grade school through medical school if she chooses. It will exist in perpetuity, so other children like her can follow, too.”

Marcus’s throat tightened. “That’s too much.”

“It’s not enough,” Jonathan replied. His voice cracked. “You gave me back my daughter. There isn’t enough in the world for that.”

Six weeks after the discovery, Elena made her first deliberate sentence.

The team had expanded the sound-code into letters. Slow, painstaking, like trying to type on a keyboard where each key required a drumbeat. It took fifteen minutes to spell out two words.

T-H-A-N-K Y-O-U.

Marcus was in the room when she managed it. Dr. Chen’s eyes brimmed. The nurses clapped quietly, like churchgoers. Jonathan Montgomery wept openly, his hand on his daughter’s shoulder.

Elena’s eyes fluttered again, insistently. She wanted to keep going.

M-A-R-C-U-S.

The room went silent. Marcus froze, mop handle still in his grip.

“She’s thanking you,” Dr. Chen said softly.

Marcus bowed his head, not trusting himself to speak.

Treatment began. Carefully tapered withdrawal of the supplements. Neuro-rehabilitation. Weeks turned into months. Elena’s muscles re-learned the art of small movements, then larger ones. She transitioned from eye flutters to finger twitches, from sound-code to a communication device that tracked her gaze across letters.

And then, one crisp morning in November, six months after Marcus had knocked over a plant, Elena spoke her first audible word.

“Hi.”

It was raspy, broken, but it was hers.

Jonathan collapsed into a chair, sobbing. Dr. Chen wiped her eyes. Marcus, standing quietly at the back of the room, closed his eyes and whispered, “Welcome back.”

Elena walked out of Saint Mary’s with cameras flashing, microphones crowding. She paused at the podium, the Montgomery family flanking her.

“Sometimes the most important observations,” she told the reporters, her voice strong now, “come not from the most educated eyes, but from the most caring ones. Mr. Marcus Williams didn’t just save my life. He reminded us that healing is about seeing people—really seeing them—and caring enough to notice what others miss.”

She gestured for Marcus to step beside her. Reluctantly, he did, mop nowhere in sight, just a simple man in his best shirt. Amy was in the front row, beaming.

The Montgomery family had already launched the Amy Williams Scholarship, but Elena insisted on making it public. The cameras caught Marcus holding his daughter’s hand, and for the first time, he didn’t feel like an invisible man.

That night, back at their small apartment, Marcus tucked Amy into bed. She clutched her stuffed elephant, eyes bright.

“Daddy,” she whispered, “today they said you’re a hero.”

Marcus smiled, brushing her hair back. “Heroes are just people who care enough to pay attention, sweetheart.”

Amy snuggled into her blanket. “Then I’m going to be a hero too.”

Marcus kissed her forehead. “You already are.”

And in the quiet, he thought of Elena, walking free. He thought of Aunt Mildred’s scholarship in another life, of Sarah’s memory, of Amy’s future. He thought about how sometimes the smallest sounds can change the biggest stories.

And he finally allowed himself to believe it: the janitor’s observation had been worth more than twenty medical degrees combined.

The End.

News

“Get her ready to welcome Skylar home.” “Sir, she’s gone—leaving only the divorce papers.” CH2

Part I: The first time Ethan Cole disappeared after another woman, I told myself it was a phase. The second…

My Sister Slept With My Husband And Got Pregnant, My Parents Sided With Her And Demand I Support… CH2

Part I My name is Lisa Wyn, and I learned early that responsibility wears a face. It looks like the…

They Called My Phone a ‘Brick’—Then I Used It to Buy Their Companies… CH2

Part I: They say the most dangerous person in the room is the one everyone underestimates. I learned that in…

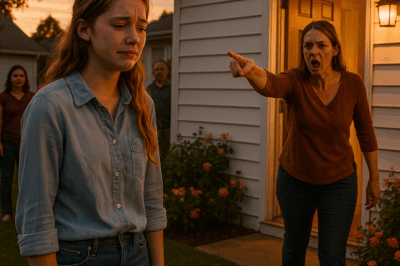

Mom Yelled at Me to “Get Out and Never Come Back” — Weeks Later, Dad Asked Why I Stopped Coming… CH2

Part I: Mom’s voice ricocheted off the doorframe and into the hot July evening. “Get out and never come back.”…

I RETURNED FROM MY TOUR TO FIND MY 9-YEAR-OLD SON ON THE FLOOR. HIS CUSTOM WHEELCHAIR WAS… CH2

Part I: The first thing I saw when I stepped through the door wasn’t my wife. It was my boy—nine…

Husband Moved to Barcelona with Mistress While I Picked Up Our Son—Until He Returned… CH2

Part I: The rain in Portland didn’t fall so much as it insisted. It was the kind of rain that…

End of content

No more pages to load