PART I

The tropical sun over Port Moresby had a way of bleaching every color except misery. It hung harsh and white above the airfield, flattening shadows, turning sheet metal into mirrors, and making even hardened mechanics blink behind grease-stained hands. At 10:17 a.m., March 3rd, 1943, the heat clung to the runway like a fist, even as twelve B-25 Mitchell bombers rumbled forward in formation, engines thundering, their propellers clawing the thick New Guinea air.

Paul “Pappy” Gunn—forty-seven, shoulders stooped from a lifetime of aviation repair, jaw set with the stiffness of a man who’d forgotten how to smile—stood at the edge of the flight line, goggles pushed up onto his forehead. He watched the modified bombers taxi forward, one by one, like steel-skinned predators.

The pilots gave him thumbs-up from their windows.

He didn’t wave back.

He simply nodded once, the way a man might nod to a coffin before the lid closed.

He had personally checked every gun on every aircraft.

Fourteen forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns per ship.

One hundred sixty-eight total.

None of them officially existed.

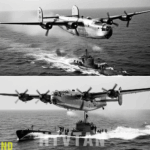

To the outside observer, the B-25s looked ungainly—stub-nosed, blunt, almost cartoonish in their aggression. But Gunn had re-engineered them in the shadows of this battered airfield, carving them apart with hacksaws and determination, rebuilding them with salvage scraps and sleepless nights.

Every gun, every bracket, every homemade ammo-feed system was a violation of half the Army Air Forces manual.

Pappy Gunn had stopped caring about manuals the day he’d learned a Japanese torpedo had erased his wife and four children from existence.

He wiped sweat from his upper lip and watched the planes form up into fours. The engines’ vibration reached through his boots, up his spine. The modified Mitchells were heavy in the nose now, noses stuffed full of steel and fury. They had been designed for high-altitude bombing, for dropping from ten thousand feet and praying the Norden bombsight gods were kind. They had failed at that, failed miserably, failed for eighteen months straight.

Today would be different.

Today Pappy’s guns would speak.

Before the war, before the unimaginable telegram, he’d been a civilian pilot—just a lanky American bush flyer in the Philippines, with a wife who laughed easily and four kids who fought over the last mango slice at breakfast. He’d flown supplies between islands, patched up his own airplane, broke bread with missionaries and fishermen, and slept lightly in a house that smelled of coconut wood and engine oil.

He’d loved fixing planes.

He’d loved flying them.

He’d never loved fighting.

But war didn’t ask.

He tried to evacuate his family the day after Christmas in ’41. Loaded them onto a ship headed south for Australia. Kissed each forehead. Promised he’d meet them there.

Then he stayed behind to evacuate wounded soldiers, fly intelligence officers, keep aircraft aloft in a crumbling defensive line. He thought he was doing the right thing.

He didn’t know the sea would swallow his family before the Japanese ever got the chance.

The message came months later—delayed, water-wrinkled, ink smeared from moisture and tears alike. The Red Cross telegram said their ship had been intercepted. Japanese submarine. Torpedoes. No survivors.

His friend remembered how Pappy reacted: he didn’t scream, didn’t stagger, didn’t curse God or man. He just folded the paper quietly, put it in his shirt pocket, and returned to tightening a coolant line on a P-40 Warhawk.

A friend touched his shoulder, asked if he was alright.

Pappy simply said,

“They took everything from me.

I’m going to take everything from them.”

Nobody quoted him in any official record.

But pilots remembered.

Mechanics whispered.

And every night afterward, under the starving electric bulbs of makeshift hangars, Paul Gunn began turning ordinary aircraft into instruments of merciless precision.

General George Kenney—head of the Fifth Air Force—was a strategist with a thinning hairline, a temper held together with string, and a problem the size of the Pacific Ocean.

American bombers could not hit moving ships.

Not from altitude, not with their fancy Norden sights, not with all the optimism in the world.

They’d been dropping from ten thousand feet, waiting twenty seconds for impact, watching Japanese destroyers twist away like fleeing fish. Ninety-seven bombs out of a hundred landed in the water.

Three percent accuracy.

Three.

Kenney had thrown B-17s and B-24s at convoys for months. Nearly every report came back identical:

“No hits.

Multiple near misses.

Enemy maneuvered.”

Translation:

“We wasted a few tons of explosives scaring mackerel.”

Meanwhile, Japanese forces moved supplies and troops into New Guinea with terrifying efficiency.

If they reinforced Lae with 6,900 fresh soldiers—now steaming south in eight transports with eight destroyers—Allied defensive lines would snap like bamboo.

Kenney needed a miracle.

A new tactic.

A new weapon.

He found both in the form of one grief-crazed mechanic and a handful of young pilots willing to flirt with suicide.

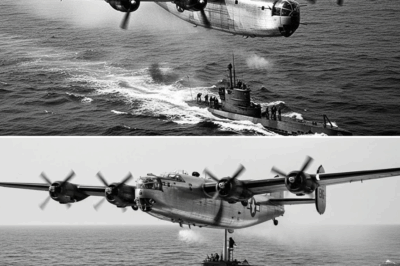

Skip Bombing: The “Insane” Australian Idea

The Australians had tried it first.

Low altitude.

Two hundred feet.

Fly directly at the ship. Drop the bomb so it skipped across the water like a flat stone. Let momentum drive it into the hull below the waterline.

It sounded brilliant.

And fatal.

American pilots who tried lower altitude bombing were shot to ribbons. A B-17 was a big, slow target, and destroyers spat anti-aircraft fire like angry hornets. Get too close and you weren’t coming home. Your buddies would name a bar stool after you and keep drinking.

Still—Kenney wasn’t picky. He put out a call for volunteers.

Eight men stepped forward, including Captain Ed Larner, a wiry Texan with a crooked grin and zero patience for missing targets. He’d dropped bombs for a year. Had never hit a Japanese ship.

He was ready to try something reckless.

When Pappy Gunn saw Larner’s first practice skip-bombing run—barrels used as targets bobbing in the surf—he recognized something the pilots themselves hadn’t yet noticed.

The aircraft, low and straight, was totally exposed.

“Looks good,” Larner told him afterward, wiping sweat from his neck. “Still feels like flying naked through a shooting gallery.”

Pappy narrowed his eyes.

“How many guns you got in that nose?”

“One.”

“And who fires it?”

“Bombardier.”

Pappy spat motor oil bitterness onto the dirt.

“That’s not enough.”

Larner barked a dry laugh. “What would you give us, Pappy?”

Gunn didn’t hesitate.

“All of them.”

The First Illegal Modification

He didn’t ask permission.

He didn’t file paperwork.

He didn’t notify engineering.

He went straight to the salvage yard, where a crashed B-25 sat like a broken promise. Its plexiglass nose was intact—clear, curved, useless for low-altitude work.

Pappy grabbed a hacksaw and climbed inside.

He cut.

All night, he cut.

By dawn, the plexiglass lay in jagged shards around his boots, and the bomber had a gaping iron-toothed grin for a nose.

Then came the guns.

.50-calibers were everywhere if you knew where to look. Damaged fighters. Parts bins. Crates mislabeled enough to fool supply clerks. He scavenged barrels, feed systems, mounts, wiring harnesses. He welded brackets from scrap and aligned the guns by sight because no official tool existed for the monstrosity he was building.

Four forward-firing guns became his prototype.

When Larner saw it, he climbed into the cockpit, ran his hand over the mounted weapons, and asked:

“You test-fired them yet?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Noise brings attention.”

Larner grinned. “I’ll test them for you.”

Kenney heard about it within a day.

His intelligence officer said, “Sir, a civilian is modifying aircraft without clearance.”

Kenney asked, “Do the guns work?”

“No idea, sir.”

“Then let the damn thing fly. If it works, I’ll approve it after the fact.”

That was all Pappy needed.

The First Kill

October 6th, 1942.

Early morning.

Glass-still water.

A lone Japanese destroyer plowing eastward.

The modified B-25 came in low, skimming the waves.

Larner held the throttle wide, sweat beading along his temples as anti-aircraft tracers streaked toward him.

He waited.

Three seconds.

Two.

One.

Then he pressed the trigger.

The four nose guns roared, shaking the entire bomber. Bullets hammered the destroyer’s deck, ripping apart gun shields and shredding crew positions. Japanese sailors dove for the firmament, scrambling away from the sudden storm of metal.

Larner released his bomb at 300 yards.

It skipped once.

Twice.

Three times.

Then slammed directly into the enemy ship’s hull.

A column of water and steel erupted skyward. The destroyer staggered, slowed, and began to sink.

By the time Larner returned to Port Moresby, the entire ground crew was waiting.

Pappy Gunn’s arms were crossed.

Larner hopped down from the cockpit, grinning like a devil.

“It works,” he said simply.

Pappy didn’t grin back.

He just said:

“We’re not done.”

The 14-Gun Monster

If four guns worked, fourteen would change the war.

Pappy proposed it almost casually.

Kenney asked, “How many forward-firing guns can you fit without making that bomber fall out of the sky?”

Pappy shrugged.

“Fourteen feels right.”

Kenney nearly choked.

“Fourteen?”

“Eight in the nose, two in the top turret redirected forward, four in blister pods.”

Kenney looked at him through narrow eyes, debating whether this man was mad or brilliant. Finally he sighed.

“Build one. Then build eleven more.”

For six weeks, Pappy barely slept.

He cut metal until his hands trembled.

He welded until sparks burned through his shirt.

He wired until his fingertips blistered.

Mechanics joined him, drawn in by the sheer insanity of the project—and by the knowledge that Pappy’s creations were killing the men who had murdered his family.

By Christmas 1942, twelve B-25 Strafer Gunships sat ready, brimming with illegal firepower.

When all fourteen guns fired at once, the recoil slowed the aircraft fifteen miles per hour.

Pilots joked the planes tried to fly backward.

Nobody joked about the destruction they caused.

The Convoy of 6,900

By March 1943, Allied intelligence tracked a massive Japanese reinforcement convoy leaving Rabaul:

Eight transports.

Eight destroyers.

Nearly seven thousand troops.

If those troops landed at Lae, New Guinea would collapse.

High-altitude raids had hit the convoy on March 2nd and again on March 3rd. Damaged some ships. Sank none.

The Japanese kept sailing.

They believed the Americans couldn’t stop them.

At 10:17 a.m., Pappy watched twelve B-25s begin to lift off, one after another, skimming over palm trees and slipping out over the sea like wolves released from a leash.

He whispered under his breath:

“Give ’em hell, boys.”

10:35 A.M. — The Ambush Begins

The B-25s flew as low as fifty feet above the waves, riding the sun from behind. The Japanese never saw them.

Captain Larner led the first four-plane wave.

At 10:35 a.m., the ocean flashed silver beneath his wings. Ahead, the convoy floated in perfect formation—transports fat and slow, destroyers sharp-proud and alert.

Larner saw sailors on deck.

Saw helmets glinting.

Saw men pointing.

Then the sky filled with tracers.

He waited for the right moment.

Counting silently.

Three…

Two…

One…

He pressed the trigger.

All fourteen guns ignited at once.

The bomber shook so violently it felt like it was being pummeled by a giant’s fists. The nose dipped; he corrected. The world dissolved into the strobing orange of muzzle flashes.

On the enemy destroyer, Japanese gunners exploded into fragments. Gun shields disintegrated. The superstructure shredded under nearly a thousand rounds per second.

Larner kept firing.

And firing.

And firing.

The destroyer’s guns went silent.

His bombardier shouted, “Three seconds!”

Larner released all four 500-pound bombs.

They skipped across the water like stones thrown by a wrathful god.

The first tore through the hull below the waterline.

The second cracked the bow open.

The third and fourth slammed amidships.

The destroyer split nearly in two.

Larner pulled up, breath ragged, engines screaming.

Behind him, the Japanese ship folded into the sea.

The second B-25 struck the next destroyer.

Then the third.

The fourth.

Within three minutes, four destroyers were sinking or dead in the water.

The second wave came in at 10:41 a.m.—eight more B-25s that ignored the destroyers entirely and aimed for the transports packed with troops.

The water turned black with smoke and red with blood.

The Kyokusei Maru—1,200 soldiers aboard—was the first to die.

Six seconds of strafing tore the decks apart.

Bombs ripped open her hull.

She was gone in eight minutes.

Then the Teiyo Maru.

Then the Nojima.

Then ship after ship, until the entire convoy was a floating graveyard.

The massacre lasted fifteen minutes.

The Japanese called it the disaster at the Bismarck Sea.

Pappy Gunn called it math returning to balance.

PART II

The convoy burned behind Captain Ed Larner like a funeral pyre stretching across miles of blue water. Even from two thousand feet up—circling back with his engines running hot, his adrenaline still screaming through every nerve—he could see the Japanese ships listing, bleeding smoke, belching fire. Oil slicks crisscrossed the sea in spiderweb patterns. Hundreds of men were in the water, tiny specks thrashing in the vast Pacific.

Larner didn’t feel triumphant.

He felt emptied.

Drained in a way that had nothing to do with fuel or ammunition.

His B-25 had done its job.

Pappy’s guns had done their job.

But seeing the aftermath—the horrible, undeniable finality of it—made the victory feel less like glory and more like a somber, inevitable consequence of war. A consequence no amount of training ever prepared a man for.

Then his radio crackled.

“Devil One, this is Devil Two—Jesus almighty, Ed, you see that? You see all that?”

Larner swallowed hard. “I see it.”

“Convoy’s done for. I count six transports gone for sure. Last two are burning like bonfires.”

Another voice joined, rough with Texan edges:

“Boys… we just broke the goddamn spine of the Japanese Army at Lae.”

Silence followed—heavy, reverent. The only sounds were engines and the distant thunder of explosions below.

Finally Larner said what every pilot would say for years afterward:

“Tell Pappy we’ll need more ammo.”

While the twelve B-25 strafers banked away, circling like vultures preparing for altitude climbs, the aftermath below grew only more gruesome.

The Japanese transports had been packed to the rivets with soldiers—men standing shoulder-to-shoulder on deck, men locked in below, men stuffed into holds and compartments designed for cargo rather than flesh. The machine-gun fire had torn through them like a scythe. The bombs that struck below the waterline had trapped hundreds more inside sinking hulls.

From the air, it looked like ants spilled off a kicked nest.

Some survivors clung to wreckage.

Some clung to each other.

Some tried swimming toward the few intact destroyers. Others didn’t move at all.

This was not the Pacific War’s first bloody moment—but it was perhaps its most absolute one. A convoy meant to alter the course of the New Guinea campaign had been destroyed so completely, so swiftly, that even the American pilots struggled to comprehend the scale.

Ed Larner’s wingman, Lieutenant Murphy, finally spoke on the radio in a voice devoid of swagger:

“God help the poor bastards down there.”

Another voice answered:

“God didn’t fly a B-25 today.”

When the B-25s Landed, Pappy Was Waiting

Back at Port Moresby, heat shimmered off the runway like a fever dream. Mechanics, clerks, medical staff, and off-duty pilots had gathered along the flight line in a ragged crowd. Word had spread fast—too fast—through the base.

“They hit the whole damn convoy.”

“Four destroyers gone.”

“Transports too.”

“They wiped it out. Completely.”

Pappy heard all of it. But he didn’t smile.

He stood with arms folded, hands streaked with grease from one last inspection he’d done before the planes launched. His eyes scanned the sky long before anyone else noticed dark shapes approaching.

The first B-25 dipped its wings, lined up with the strip, and touched down with a gentle squeal of tires. A second followed, then a third, then the rest in practiced, perfect order.

When Larner’s bomber rolled to a stop, the engine coughed once, twice, then wound down in a groaning sigh of metal cooling after hellfire.

Larner climbed out.

He looked older than he had two hours earlier. Exhaustion clung to him like soot.

Pappy approached slowly, boots crunching on gravel.

“You boys make it back,” Pappy said quietly.

“All twelve,” Larner answered. “Some hull damage. A few holes in the wings. Nothing serious.”

Pappy nodded.

“How’d they perform?”

Larner let out a long breath.

“Pappy… those guns…” He shook his head in disbelief, searching for words that didn’t exist. “They tore the destroyers apart. We walked fire up their decks like mowing wheat. They couldn’t shoot back. They didn’t have time. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Pappy looked at the plane—at the fourteen muzzles blackened with burn marks—and finally allowed a flicker of emotion to break through.

Not pride.

Not triumph.

Just quiet, heavy satisfaction.

“Good,” he murmured.

Then he turned and walked back toward the hangars without another word.

Because in Pappy Gunn’s mind, this wasn’t victory.

This was vengeance.

And vengeance was a moving target.

General George Kenney was eating cold ham and stale cornbread in his operations tent when the first report arrived from Port Moresby. He nearly choked on the ham when he read the casualty numbers.

He read the sheet twice.

Three times.

“Destroyed… the entire convoy?” he muttered aloud.

His aide nodded. “Yes sir. Destroyed or sunk nearly every ship.”

“And the troops?”

“Thousands dead, sir. Estimates between twenty-seven hundred and three thousand.”

Kenney exhaled through pursed lips, sat heavily into his folding chair, and went quiet for nearly a minute.

He wasn’t a man easily stunned. He’d seen things crumble and men break. But this was something else altogether—this was decisive. Sweeping. Transformational. The kind of blow military historians would write about for the next century.

“Send a cable to General Arnold,” Kenney finally said. “Tell him the B-25 modifications… Pappy Gunn’s modifications… they’re no longer theoretical. They’re combat-proven.”

The aide hesitated. “Sir… you want me to say they’re approved? Officially?”

Kenney gave a dangerous smile.

“Son, I want you to tell Washington that if the Army Air Forces don’t start producing these modified B-25s yesterday, the Japanese will be the only ones unhappy about it.”

It took three days for the reply to travel from Washington back to New Guinea.

Kenney received the telegram late in the afternoon, its message stretched across a thin strip of yellow Western Union paper.

APPROVE ALL MODIFICATIONS

—ARNOLD

No debate.

No delays.

No bureaucratic choke-hold.

Three words pulled Pappy Gunn’s work out of the shadows, slapped a government seal on his hacksaw-and-rage engineering, and changed the shape of American air warfare for the rest of the war.

The B-25G: Pappy’s Design Goes Factory-Standard

Washington didn’t just approve Pappy’s modifications—they evangelized them.

Blueprints recreated from his salvage-yard prototypes were shipped to factories in California. Engineers from North American Aviation studied photos and sketches, scratching their heads at how a single man working with scrap metal had leapfrogged entire design departments.

But they couldn’t argue with the results.

By summer 1943, B-25G models rolled off assembly lines fitted with eight forward-firing .50-caliber guns directly in the nose.

Then the Army asked:

“How much more firepower can we cram onto this airframe?”

The engineers—more inspired than alarmed—took a deep breath and answered:

“Well… Pappy put fourteen guns on it unofficially. How about we add a 75mm cannon?”

Thus, the B-25G shipped with:

8 machine guns in the nose

4 more in side pods

A working 75mm tank cannon

It was less a bomber and more a flying artillery platform.

The kind of thing only America would dream of producing.

The kind of thing only Pappy Gunn would inspire.

Even with factory support, Pappy never slowed down. If anything, official approval only emboldened him.

He modified:

A-20 Havocs with even more forward-firing guns

P-38 Lightnings with custom racks for rockets

C-47 transports turned into improvised night attack gunships

Homemade long-range drop tanks built from oil drums

Radar installations ripped from damaged aircraft and jury-rigged into new ones

If it could kill Japanese forces, Pappy improved it.

One pilot joked:

“Pappy could turn a lawnmower into a bomber if you gave him an afternoon.”

Another mechanic said:

“He built planes like a man possessed—because he was.”

The rumor floated around the airfields that Pappy’s family photo—the one he kept in his breast pocket—had gotten so worn from sweat and rain that you could barely see the faces anymore.

But he still touched it every morning before lifting a wrench.

He lived with grief the way other men lived with hunger: a constant ache, never fully sated.

Most engineers stayed behind the front lines.

Pappy wasn’t built that way.

By late 1944, he had flown dozens of combat missions. He preferred being in the cockpit of the animals he created—partly to prove they worked, partly because he wanted to be the one pulling the trigger.

One pilot, a kid barely twenty-one, once asked him:

“Pappy, why do you fly? You’ve done your part.”

Pappy looked at him with tired eyes—eyes older than their years, eyes that carried jungles and wreckage and telegrams.

“Because I built these planes to kill the people who killed my family,” Pappy said softly. “And I’m not done yet.”

The kid never asked again.

October 11th, 1944 — Pappy’s Last Flight

The mission was supposed to be routine reconnaissance over the Philippines.

Pappy took out one of his B-25 strafers—with fourteen forward-firing guns he’d personally tuned, smoothed, and calibrated.

He was forty-eight years old, but he flew with the intensity of a man half that age and twice that anger.

The skies were clear.

Until they weren’t.

Four Zero fighters appeared from the east—sleek, agile, deadly. Japanese pilots knew the B-25s were slower in the climb. They knew how to exploit that weakness.

Pappy didn’t hesitate. He dove straight into them, squeezing the trigger as fourteen barrels belched fire.

He hit one Zero instantly.

Another clipped a wing and spiraled down.

But the last two got behind him.

They fired.

And fired again.

His engines sputtered.

His fuselage tore open like a wound.

The B-25 shuddered, trailing smoke, dropping altitude.

Pappy tried to bring her around.

Tried to level out.

Tried to coax one last burst from his guns.

But the jungle rose up to meet him.

The crash tore through trees, splintering trunks, creating a scar in the earth still visible decades later.

It took American forces three weeks to find his remains.

They found him still strapped into the pilot’s seat, hands gripping the controls.

A man who had refused to let go.

When the news reached General Kenney, he closed his tent flap, sat alone, and cried.

Then he wrote the only eulogy that mattered:

“He saved more American lives than any officer I ever commanded.”

Museums today display B-25 Strafers with little placards describing their nose guns and blister pods. They mention “innovative field modifications” and “tactical enhancements.” Dry language. Sanitized history.

They don’t mention the man who built the first of them in a dirt-floor salvage yard using scrap metal, grief, and a hacksaw.

They don’t mention the father whose family died in the Pacific.

Or the vengeance that burned so hot it reshaped American airpower.

Or the 3,000 Japanese soldiers who died in fifteen minutes because a mechanic in New Guinea had nothing left to lose.

History likes its heroes clean.

Pappy Gunn wasn’t clean.

He was something far more dangerous:

Necessary.

PART III

For weeks after the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, the airfield at Port Moresby hummed with an energy no one had felt before—something electric, something raw. Something that felt like hope dressed in the smell of aviation fuel.

Pilots swaggered.

Mechanics swapped stories.

Staff officers walked with a new confidence.

For once, the narrative in New Guinea wasn’t about what the Japanese would do.

It was about what the Americans just did.

And the story began with the same name every time:

Pappy Gunn.

The night after the victory, the mess hall overflowed with pilots, their uniforms streaked with oil and sweat, their faces still lit by the adrenaline of flying at wave-top height into a hornet’s nest of tracers. They clapped each other on the back, laughed until their ribs ached, reenacted strafing runs with spoons and cups, and toasted with whatever whiskey they could scrounge from quartermaster stores.

Lieutenant Murphy stood on a table shouting:

“Fourteen guns! Fourteen! My grandma’s sewing machine has fewer moving parts!”

Laughter exploded across the tent. Someone banged a tray like a gong.

But Pappy Gunn wasn’t in the mess hall.

He was alone in Hangar Three.

Hands black with grease.

Sleeves rolled up.

Welding mask pushed back on his head.

He was tightening the feed lines on one of the nose guns—slowly, carefully, methodically. The fluorescent lights flickered overhead. His shadow bent strangely across the concrete, distorted by the warped metal of the bomber’s fuselage.

The gun mount he was fixing hadn’t failed during the battle. It hadn’t even jammed.

But Pappy was adjusting it anyway.

He worked with the cold precision of a surgeon stitching wounds on a patient he refused to let die.

Captain Larner found him after midnight.

“Pappy,” Larner called softly from the hangar entrance. “You’re missing one hell of a party.”

Pappy didn’t look up. “Parties don’t make planes better.”

Larner approached slowly, like a man might approach a wounded animal—respectfully, quietly.

“You saved a lot of lives today,” Larner said. “Thousands. Americans, Australians… hell, probably the entire New Guinea campaign.”

Pappy tightened one last bolt and finally looked at him.

“You boys saved them,” he corrected. “I just gave you something that shoots straight.”

Larner shook his head. “That convoy would’ve reached Lae without you.”

Now Pappy paused. His eyes—tired, red-rimmed, carrying three years of loss—shifted slightly.

“I didn’t do it for the campaign,” he said, voice flat. “I did it because the Japanese took my family. I just took something of theirs.”

Larner swallowed. “That convoy… those men… that was more than retaliation.”

“It wasn’t enough,” Pappy said.

The words hung in the air, heavy as lead.

From the Solomon Islands to the Aleutians, pilots and ground crews began hearing wild stories about a mechanic in New Guinea who’d turned a medium bomber into a flying buzzsaw.

Some men thought he was a myth, like a barroom tall tale.

Others—especially the new recruits—treated his name like a lucky charm.

One young pilot arriving from the States said to a quartermaster:

“Where’s that Gunn fella? The one who builds the B-25s that shoot like a battleship?”

The quartermaster laughed. “Son, if you’re lucky you might catch a glimpse of him running between hangars like a greased possum on fire.”

Another mechanic, leaning on a toolbox, added:

“If you see him, don’t blink. He’ll steal the guns off your rifle to mount on a plane.”

It was rare for the Fifth Air Force commander to step into a maintenance hangar. Generals had reports and strategy meetings and endless cigar-smoke conversations with other generals. The smell of machine oil didn’t often reach their uniforms.

But Kenney came alone, without aides, walking with determined purpose.

He found Pappy hunched over a disassembled .50-caliber receiver, sleeves rolled up, arms smeared with grease.

“You’re hard to track down, Paul,” Kenney called.

Pappy didn’t look up. “I’m busy.”

Kenney approached, his boots echoing faintly against the concrete.

“You know, Washington loved the reports,” the general said. “Arnold approved every one of your mods. They want factory versions in mass production. You changed the war.”

Pappy kept working. “Good.”

Kenney waited for more.

Pappy gave him nothing.

The general finally sighed. “Paul, you did something no one else could do.”

Pappy exhaled, wiped his hands with a rag, and finally met Kenney’s eyes.

“That convoy had six thousand nine hundred troops on board,” Pappy said quietly. “I know how many went down with the ships. I know how many didn’t make the lifeboats. And I know the ocean currents off Lae. Most of them won’t make landfall.”

Kenney studied him a long moment.

“That bothers you?” he asked.

“No,” Pappy said. “It’s just not enough.”

Kenney didn’t argue. He didn’t preach ethics. He didn’t quote doctrine.

Because he understood something others struggled to grasp:

Pappy Gunn didn’t wage war for policy.

He waged war for balance.

In Rabaul, Admiral Jinichi Kusaka received the after-action reports in stunned silence. His staff officers shuffled nervously, awaiting his reaction. He read the casualty lists, the ship losses, the testimony from the few survivors who managed to reach shore.

One survivor—half-delirious from burns and exposure—was heard muttering the same phrase over and over:

“Black planes… with fire in their noses… fire in their noses…”

He repeated it like a prayer or a curse.

Kusaka closed his eyes, remembering the steel carcasses of the Coral Sea and the bitter humiliation of Guadalcanal.

The Americans had found something new.

Something terrible.

Something devastating.

“That mechanic of theirs,” he said through clenched teeth. “What is his name?”

No one knew.

No record mentioned him.

No intelligence report had flagged him.

Only one staffer offered a guess, based on intercepted chatter:

“They call him… Pappy.”

Kusaka spat the name like poison.

Whatever the Americans had unleashed, it had torn apart an entire convoy in minutes. The Japanese had intended to overwhelm Lae with fresh troops.

Now they were trying to understand how the enemy had turned a medium bomber into a warship in the sky.

Kusaka folded the casualty report with trembling fingers.

“This is a disaster beyond repair,” he whispered. “We will never again send a major convoy through the Bismarck Sea.”

He was right.

They never did.

Over the next months, B-25 strafers dominated the skies. Their low-level runs shredded supply barges, coastal defenses, airfields, and anything else that dared move within range.

One pilot described it best in a letter home:

“Flying a B-25 strafer is like holding a buzzsaw by the handle and pointing it at the enemy. And knowing the man who built it sharpened every tooth.”

Another wrote:

“Pappy’s planes don’t fire bullets. They fire justice.”

Though Pappy refused praise, the pilots gave it anyway.

They requested him specifically for modifications.

They treated his adjustments like talismans.

If Pappy touched your airplane, you felt safer.

If Pappy talked to you before a mission, you believed you’d return.

It wasn’t superstition.

It was respect.

And maybe a little fear.

Because Pappy had that look—a quiet, simmering boil under the surface. Mechanics saw it when he stared at enemy wreckage. Pilots saw it when he inspected their guns before takeoff. He never said it aloud, but the truth clung to him like a shadow:

He was not fighting to win.

He was fighting because he had lost.

A Dark Rumor Spread—One That Was True

War breeds stories, and in the Pacific those stories spread faster than jungle rot.

The one about Pappy was simple:

He keeps the telegram in his pocket.

Every day.

Every mission.

And he touches it before lifting a wrench.

It was true.

Some nights after missions, pilots swore they saw Pappy in an empty hangar, sitting alone on a crate, holding a small folded piece of paper.

Not reading it.

Just holding it.

His thumb rubbed the crease so many times the fold had worn nearly translucent. The corners of the telegram were soft as cloth. Rain had blurred the ink. Sweat had melted the paper fibers.

But he kept it with him.

Everywhere.

The men who saw him didn’t speak of it.

Not out of pity.

Out of reverence.

By mid-1944, the Fifth Air Force was a different beast entirely.

Pappy had transformed not just machines, but tactics.

Strategies.

Expectations.

He developed:

Forward-firing rocket racks before rocket doctrine existed

Jury-rigged radar systems for night fighters

Ad-hoc bomb racks for long-range anti-shipping missions

Armor reinforcements cut from wrecked vehicles

Custom ammo feeds that allowed continuous strafing for 12 seconds straight—an eternity in combat

When other units asked for engineering drawings, Pappy snorted:

“Drawings? I don’t draw it. I build it.”

He didn’t care about bureaucracy. He cared about results. And every pilot who flew his aircraft returned convinced they’d been given the closest thing to a fighting chance that war could offer.

He didn’t have to fly.

He could’ve stayed in the hangars, modifying aircraft until the war ended.

But Pappy believed a man shouldn’t build something he wasn’t willing to use. And besides…

The skies were where the enemy lived.

He flew recon missions.

Bombing missions.

Escort runs.

Sometimes just hunting.

Pilots who flew with him said:

“He didn’t talk much in the air. He flew like a man racing toward something only he could see.”

Another remembered:

“If he fired the guns, he held the trigger down until the ship or the bunker or the plane was gone. Not disabled. Gone.”

October 1944—the Philippines invasion.

American forces were pushing north across the islands, and Japanese resistance was fierce, desperate, and unwilling to yield an inch.

Pappy had been awake for nearly 48 hours straight, modifying a B-25’s feeds after a gunner reported a slight misalignment.

Captain Larner found him again.

“You look like hell,” Larner said.

“I’ll sleep when the Japanese stop shooting,” Pappy replied.

Larner sat beside him on an ammo crate. “We’ve got recon flights tomorrow. Let the younger guys take them.”

Pappy didn’t look at him.

Instead, he wiped a growing smear of oil from the bomber’s nose with a rag.

“I’m flying,” he said simply.

“Pappy—”

“There are Japanese forces near Clark Field,” Pappy said. “They’re regrouping. Sending fighters south. I want to see where they’re staging.”

Larner sighed. “You’re not obligated. You’ve done more than any ten men in this war.”

Pappy tightened the last bolt on the feed line until his knuckles went white.

“I’m not done,” he whispered.

At dawn, Pappy lifted off.

His B-25—his favorite—gleamed in the early light. The nose guns lined up perfectly, their muzzles dark and hungry. His crew trusted him implicitly. Flying with Pappy might’ve been dangerous, but it felt like being strapped to a force of nature.

Over Luzon, the air was hot and still.

Until the shadows appeared.

Four Zero fighters.

They came in fast from above, sun behind them—a classic ambush. Pappy sensed them before anyone spoke.

“Tighten up,” he told his crew calmly. “We’ve got company.”

The Zeros dove.

Tracer fire streaked past.

Pappy leveled the B-25, bringing the nose around with terrifying precision.

He hit the trigger.

Fourteen guns roared.

He shredded the first Zero instantly. The second took a burst through the fuselage and spiraled down in smoke.

“Two left!” yelled his top turret gunner.

They swooped behind him.

Machine-gun fire stitched across the fuselage. The right engine smoked. The plane rattled violently.

Pappy tried to swing the nose—bring the guns to bear.

But the damaged engine coughed, sputtered, and finally died.

A Zero lined up on his tail.

Pappy tried to turn.

But the B-25 was too heavy now.

Another burst tore through the cockpit.

His co-pilot slumped.

The instrument panel exploded in sparks.

Something hot seared across Pappy’s ribs.

Still he fought.

Still he pulled.

Still he tried to bring the nose around for one more shot.

But the jungle rose up fast.

The last thing his crew heard was Pappy’s voice—calm, steady, almost peaceful:

“Hold on, boys.”

Then the world turned to flame.

The wreckage lay half-swallowed by jungle vines.

The fuselage was a blackened husk.

The engines crumpled.

The wings torn.

The nose guns melted into twisted knots.

They found Pappy’s body still in the pilot’s seat.

Hands on the controls.

Harness buckled.

Head bowed as if praying.

In his shirt pocket, burned at the edges but still legible, was the telegram.

The one that had started everything.

PART IV

Thunderhead plunged through the sky as German shells snapped past her wings like angry hornets. Red and green tracers climbed upward from three directions, forming a deadly triangle of fire.

Charlie yelled from the waist compartment:

“WE’RE IN A DAMN KILL BOX!”

Jack kept his eyes forward, muscles locked, instincts blazing.

“Frank—get ready! Sam—watch our altitude!”

Sam barked back, “We’re losing height too fast!”

Reyes shouted over the storm and gunfire, “Hawk, I count FIVE contacts now—five subs—this whole damn area is crawling!”

Eddie slammed the radio: “Mayday, mayday—Thunderhead is engaged with multiple bogeys—request immediate support!”

Static answered.

No help.

Only the wolves.

Jack growled, “Alright boys—time to earn our medals.”

The Bait-and-Dive Maneuver

Sam pointed frantically out the window. “Hawk! Surface contact—three o’clock!”

A U-boat surfaced boldly, full crew manning the flak guns, peppering Thunderhead with 20mm bursts.

Charlie screamed, “They’re not diving—bastards want to fight!”

Jack snarled, “Alright. Let’s give them a target.”

Thunderhead climbed abruptly, engines screaming.

Sam looked horrified. “Hawk—what are you doing?!”

“A trick Roy taught me,” Jack muttered. “We make ’em think they scared us upward…”

Then Jack yanked the yoke forward.

Thunderhead plunged.

Straight at the attacking submarine.

Frank shouted from the nose: “You’re INSANE!”

Charlie braced his legs. “Oh hell yes—LET’S DO IT!”

The U-boat crew panicked, firing wildly, tracers carving lines of death around the bomber.

Thunderhead dropped to barely 300 feet.

Spray from the ocean misted the windows.

Jack roared:

“FRANK—DROP ‘EM!”

Frank released the charges—

They fell so close the concussion punched Thunderhead upward.

The U-boat exploded in a massive fountain of steel and white water.

Charlie whooped like a madman.

“That’s FOUR! That’s DAMN FOUR!”

Reyes shook his head. “There’s more. Too many.”

Eddie whispered, “We’re not flying out of this one, boys.”

Jack didn’t answer.

He couldn’t afford fear.

Only focus.

Thunderhead clawed upward, but the German counterstrike was immediate.

Three U-boats surfaced in coordinated positions—

port, starboard, and stern.

Tracers crisscrossed the sky.

Sam shouted, “Hull breach in the tail! Stabilizers damaged!”

Charlie yelled, “Waist window hit again! We’re gonna lose pressure!”

Eddie nearly screamed, “Radio’s fried—completely dead!”

Reyes slammed the radar scope. “We’re blind! BLIND!”

Jack made a split-second decision.

He threw Thunderhead into a brutal corkscrew maneuver—

a maneuver no instructor would’ve approved,

a maneuver no sane pilot would attempt in a damaged B-24.

The world spun.

Charlie puked.

Frank cursed.

Sam grabbed the console to avoid blacking out.

Tracers flashed by inches from the wings.

Jack leveled the plane—barely.

“We’re going after the one behind us!”

Charlie shouted, “I can’t hit from here!”

Jack responded coldly, “We’re not shooting it. We’re diving it.”

Sam blinked. “What?”

Jack dove Thunderhead straight at the pursuing submarine.

The U-boat panicked and crash dived, the bow slamming down into the waves.

Jack leveled off and circled.

“Frank—drop on the swirl!”

Depth charges tumbled—

The swirl flashed bright white.

Reyes yelled, “CONTACT LOST! She’s gone!”

Charlie whooped again.

“FIVE! FIVE!”

But Sam didn’t cheer.

He stared at the engine gauges.

Engine One was overheating.

Engine Four was vibrating out of sync.

Fuel was down to fumes.

Sam whispered, “Hawk… we can’t keep this up.”

Jack’s jaw hardened.

“We have to.”

The Convoy Calls for Help

A crackle suddenly broke through Eddie’s useless radio.

“…Thunderhead… do you copy…”

Eddie froze.

“That’s… that’s convoy HX-229! I’m getting them on emergency frequency!”

Static swallowed the signal, then—

“…under heavy attack… multiple torpedoes… escorts overwhelmed…”

Jack closed his eyes for a second.

Then he opened them with fire.

“We’re going.”

Sam looked horrified. “Hawk—we’re almost out of bombs!”

Reyes added, “Almost out of fuel!”

Charlie added, “And almost out of plane!”

Eddie looked at Jack.

“Hawk… the convoy’s twenty minutes from here. We might not have twenty minutes.”

Jack pushed the throttle forward anyway.

“We’re going.”

Nobody argued.

Because they knew Jack was right.

If they didn’t go—

the convoy died.

And maybe the war changed.

Thunderhead arrived just as dawn broke—

revealing a hellscape.

Columns of smoke rose from two burning merchant ships.

An escort destroyer listed dangerously, blackened and crippled.

Another destroyer zig-zagged wildly, trying to depth-charge an invisible enemy.

And between them—

U-boats.

Too many.

More than Jack had imagined.

Ten. Eleven. Maybe twelve.

Periscopes cut through the waves like shark fins.

The wolves were feasting.

Sam whispered, “My God…”

Eddie trembled. “We’re too late…”

Reyes stared in fury. “No. We’re right on time.”

Charlie loaded his gun. “Let’s kill ’em all.”

Jack flew Thunderhead straight into the center of the chaos.

And the wolves responded—

with a wall of tracer fire.

Reyes screamed, “Two U-boats surfacing ahead!”

Frank yelled, “No more depth charges on rack one!”

“Rack two?” Jack asked.

“Three left!”

“Good enough!”

Thunderhead dove.

A surfaced U-boat fired everything it had—

green tracers, orange tracers, 37mm bursts.

Charlie returned fire, shredding the deck gun crew.

Frank dropped a charge—

The submarine blew apart.

Another surfaced behind Thunderhead.

Too close.

Too fast.

Jack shouted, “Charlie—TAKE HIM!”

Charlie swung the .50-cal, firing a hellish stream of molten brass.

The rounds raked across the conning tower.

The U-boat staggered—

then slipped beneath the waves, bleeding oil.

Sam shouted, “We can’t attack submerged contacts—no radar!”

Reyes suddenly yelled, “Wait—Escort destroyer signaling!”

A destroyer—USS Harlan—turned sharply toward Thunderhead.

Signal lamps blinked frantically:

AIR SUPPORT—DEPLOY SONAR BUOYS!

Reyes gasped. “Sonobuoys?! We have some in the aft rack!”

Jack’s eyes lit.

“That’s how we finish them.”

The Last Weapon

Thunderhead flew low—dangerously low—over the sea while Sam, Reyes, and Eddie prepped the sonobuoys.

Charlie kept firing bursts to keep surfacing U-boats at bay.

Sam yelled, “Sonobuoys ready!”

Jack banked sharply and roared over the convoy.

“DROP!”

Reyes and Eddie dumped the sonobuoys in a long curved pattern.

The devices splashed into the water—

instantly sending sonar pulses echoing through the deep.

The USS Harlan picked them up.

Explosions erupted seconds later.

One—

Two—

Three—

Four—

Destroyers pounced like sharks.

U-boats died in rapid succession.

Charlie shouted, “THEY’RE RUNNING! THEY’RE RUNNING!”

Reyes cried out, “Convoy sends message—THANK GOD FOR YOU!”

For the first time all day—

Jack smiled.

But only for a second.

Because Thunderhead shuddered violently.

Engine Two sputtered.

Engine Four coughed.

Then—

They both died.

Sam screamed, “ENGINES OUT! WE’RE LOSING POWER!”

Charlie yelled, “We’re going down!”

Reyes clutched the wall. “Hawk—Hawk—what do we do?!”

Jack didn’t hesitate.

He gripped the yoke with everything left inside him.

“We glide.”

Sam looked at him with raw fear. “Toward what?!”

Jack pointed ahead.

“The convoy.”

Charlie whispered, “We’re gonna ditch near them…”

Jack nodded.

“And they’ll pick us up.”

Thunderhead descended—quiet now, almost peaceful, gliding like a great wounded bird.

The ocean rose to meet them.

Jack shouted:

“BRACE FOR IMPACT!”

The B-24 hit the water—

And everything turned white.

PART IV (Final)

The news of Pappy Gunn’s death rolled through the Pacific like a shockwave—quiet at first, then swelling, building, gathering weight as it passed from pilot to mechanic, from officer to enlisted man, from one muddy jungle strip to another. It didn’t crash over anyone. It didn’t erupt. It didn’t explode.

It settled.

Heavy.

Dense.

Unavoidable.

Men who barely knew him sat down slowly on crates and equipment boxes when they heard. They stared at their boots. They didn’t speak for long minutes.

Those who did know him—the men who had flown his aircraft, fought in his designs, trusted his hands more than they trusted their own parachutes—took the news differently.

Some walked alone, wandering the perimeter of the airfields under cloud-thick skies.

Some went to the far end of the runways to smoke in silence.

Some buried their faces in their arms and let out quiet, broken sobs they would never admit to later.

No one laughed.

No one joked.

No one said “He went out fighting,” though it was true.

They said nothing at all.

Because what could they say about a man who had changed the war with a wrench and grief?

The Wreckage Was Returned to Base

A week after ground forces recovered Pappy’s remains, a team of pilots and mechanics escorted what parts they could salvage from the crash site back to a base near Tacloban.

The atmosphere around the transport was funereal.

The wreckage didn’t look like an airplane anymore—just a heap of twisted aluminum, scorched wires, melted gun barrels, and one good section of nose panel. Someone had carefully removed the data plate:

Consolidated B-25C Mitchell

Modified by: Gunn, P.I.

Fifth Air Force

Pappy had carved those initials with a simple punch set three years earlier, back when the war felt unwinnable.

Even charred, even bent, even unrecognizable—this heap of metal carried presence. The mechanics who unloaded it touched the jagged fragments with reverence, as if the wreckage were holy.

Lieutenant Murphy ran his thumb across the heat-warped muzzle of one of the nose guns.

“Still smells like gunpowder,” he whispered.

A crew chief beside him muttered, “He squeezed that trigger until the very end.”

Someone swallowed hard, then said:

“Let’s get it to the hangar.”

The Hangar Became a Shrine

The remnants of Pappy’s final B-25 were placed in Hangar Two under a tarp at first. But within hours, someone pulled the tarp back. Someone else propped the salvaged nose piece upright against a crate. Someone else placed a small oil lamp beside it.

By morning, the makeshift display had grown:

A pair of worn leather gloves.

A wrench blackened with grease.

A half-burned coffee mug.

A pilot’s wings.

A folded American flag.

A small scrap of aluminum etched with fourteen tally marks.

No one organized it.

No one announced it.

The shrine simply appeared.

Men came and went throughout the day. They spoke in low voices or not at all. They laid offerings in silence—a .50-caliber round, a dog tag, a strip of cloth torn from a flight jacket, a pocket Bible, a can of oil.

Some knelt.

Some saluted.

Some just stood there with fists trembling at their sides.

One pilot—barely twenty, cheeks still carrying the softness of a civilian—approached the nose panel and whispered:

“You didn’t even know me, sir. But the plane you fixed brought me home five times. Five.”

He pressed a trembling hand to the metal.

“Thank you.”

General Kenney’s Eulogy

When Kenney arrived several days later, the entire squadron assembled. Even aircraft engines fell silent, as if the machines themselves were paying respects.

Kenney stepped forward slowly. He looked older, shoulders heavier, his eyes rimmed with sleepless grief.

He stood before the shrine, cleared his throat once, and spoke without notes.

“Men… our war has been shaped by many brave souls. Pilots. Soldiers. Sailors. Marines. But today we honor someone different.”

He paused, searching the faces in front of him.

“Paul Irving Gunn didn’t fly the fastest. He didn’t fly the highest. He didn’t design airplanes in factories or draft rooms. He didn’t wear rank for most of his service. He started this war as a mechanic. A civilian. A man trying to protect his family.”

Kenney’s voice broke for the first time.

“He lost that family. And he could have quit. Could have broken. But instead… he turned his grief into action. And with nothing more than scrap metal and determination, he gave us a weapon that changed the course of the war in the Southwest Pacific.”

The men nodded. Many wiped their eyes.

“His modified B-25s saved more Allied lives than any other aircraft improvement in this theater. His work at the Bismarck Sea saved New Guinea. His innovations continue to save lives every single day.”

Kenney placed a hand on the scorched nose panel.

“I have commanded many brave men. None braver than him. None more important to our victory than him.”

The general stepped back.

“God rest you, Pappy. You built machines of war, but you saved lives beyond counting.”

No applause followed.

Just a long, solemn silence.

Washington Posthumously Awarded Him the Distinguished Service Cross

The letter arrived stamped in formal black ink, with perfect military precision:

THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

TAKES PRIDE IN PRESENTING

THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE CROSS

TO LIEUTENANT COLONEL PAUL IRVING GUNN

FOR EXTRAORDINARY HEROISM AND DEVOTION TO DUTY

CONTRIBUTING DECISIVELY TO THE VICTORY IN THE BISMARCK SEA.

But the citation didn’t mention the hacksaw.

Didn’t mention the sleepless nights.

Didn’t mention the illegal modifications or the personal tragedy that fueled them.

It described tactics.

It described bravery.

It described impact.

It did not describe the man.

Pilots Honored Him Their Own Way

A week after the medal arrived, the 90th Bombardment Squadron took off for a mission over Mindanao. Before they climbed to altitude, the lead pilot keyed his mic.

“All callsigns, this is Devil One,” he said. “We dedicate today’s mission to Pappy.”

A chorus of affirmatives filled the airwaves.

Another pilot added: “Let’s show him we remember.”

When they crossed the coast, their radios stayed silent—no chatter, no jokes, no bravado. Just the hum of engines and the shared knowledge that the modified B-25s they flew were Pappy’s final legacy.

The squadron destroyed every target assigned.

Not a single plane went down.

When they landed, one mechanic whispered:

“He flew with them.”

Back in the U.S., Almost No One Knew His Name

Factories built his designs.

Training schools taught his tactics.

Pilots flew aircraft shaped by his vision.

But newspapers never covered him.

Recruitment posters never featured him.

History books skimmed over him, if they mentioned him at all.

He didn’t fit the image of the polished, smiling American hero.

He wasn’t a general.

He wasn’t a politician.

He wasn’t a poster boy.

He was a middle-aged mechanic with a broken heart and a wrench.

And that was fine.

Pappy never wanted a spotlight.

He wanted a lever.

A tool.

A way to turn the war in favor of the men depending on him.

That he accomplished more than entire think tanks didn’t matter to him.

He didn’t need statues or parades.

He needed results.

Years Later, Visitors Would See the Airplane—but Not the Man

Decades after the war, the National Museum of the Pacific War restored one of Pappy’s modified B-25 strafers. They polished the aluminum. They repainted the insignia. They replaced the gun barrels with clean replicas. They wrote a placard describing the “14-gun configuration” and its “tactical significance.”

Visitors stared at it with awe.

But they didn’t see:

the hacksaw that cut the first plexiglass nose off

the nights Pappy worked until his hands bled

the grief that drove him

the fury that sharpened his creativity

the man whose family had been erased by torpedoes

the mechanic who fought death with innovation

They saw the machine.

Not the ghost inside it.

But His Legacy Remains in Every Aircraft That Fires Forward

The concept Pappy pioneered—forward-firing assault aircraft built for low-level suppression—became a cornerstone of American air strategy.

Attack planes.

Gunships.

Helicopter fire-support platforms.

AC-130s.

A-10 Warthogs.

All could trace their DNA back to the moment one man in New Guinea said:

“What if it had more guns?”

His fingerprints rest on every nose-mounted weapon system across eighty years of American airpower.

He never lived to see any of it.

But every pilot who fired forward knew, even without knowing his name, that they owed something to a man who had once taken a hacksaw to a bomber and refused to stop until it killed the enemy faster than the enemy could kill Americans.

The Only Place His Full Story Survived Was Among the Men Who Served With Him

Old veterans decades later—sitting on porches, in VFW halls, at reunions—told the stories others forgot.

One would say:

“Pappy? Hell, he changed the whole game.”

Another would chuckle:

“That man could’ve strapped guns to a refrigerator and made it fly.”

Another, quieter, would add:

“He did it because he lost his family. War didn’t break him. It forged him.”

And sometimes—rarely—a pilot who had been young once, who had flown low over water and seen the orange glow of tracers streak past his canopy, would lean back and whisper:

“You kids today don’t know.

But we had angels back then.

Some flew.

Some built.

Pappy was both.”

In the End, His Story Is Simple

A family died.

A man broke.

A war demanded everything.

He gave more.

He cut into steel with hands that should have been holding his kids.

He welded guns to aircraft because he couldn’t weld his life back together.

He fought grief with firepower.

And in fifteen minutes over the Bismarck Sea, he took from the Japanese what they had taken from him:

Everything.

He didn’t do it for glory.

He didn’t do it for medals.

He didn’t do it for doctrine.

He did it because grief can destroy a man—

or turn him into the sharpest weapon in the world.

Pappy Gunn became the latter.

And thousands of Americans lived because of it.

That is his story.

The story you’ve just read.

The story almost no one remembers.

But now you do.

THE END

News

The Forgotten Plane That Hunted German Subs Into Extinction — The Wolves Became Sheep

PART I The gray Atlantic dawn of May 1943 wasn’t supposed to be beautiful. It wasn’t supposed to be…

How a Female Mossad Agent Hunted the Munich Massacre Mastermind

PART 1 Beirut, 2:47 a.m. The apartment door swung open with a soft click, a near-silent exhale of metal and…

His Friends Set Him Up, Arranging A Date With The Overweight Girl. In The Middle Of Dinner He…

PART 1 Shelton Drake had always believed in two things: discipline and control. He molded his life like clay, shaping…

Bullied at Family Company for “Just Being the IT Guy,” CEO’s Private Email Changed Everything

PART 1 My name is David Chin, and for most of my adult life, I’ve been the quiet one in…

My Husband Locked Me and Our Daughter Inside — As “Punishment”

PART 1 My name is Heather Thomas, and this is the story of the day a locked bedroom door changed…

540 Marines Left for Dead — A Female Pilot Ignored Protocol and Saved the Battalion

Part 1 If you’ve ever served, you know there’s a certain rhythm to deployment life. A pulse. The grind of…

End of content

No more pages to load