The snow started as a rumor.

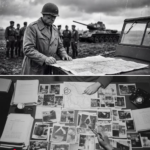

You could feel it more than see it at first—a thin, metallic chill in the air that crept under uniforms and into bones. Outside the canvas walls of the war room somewhere in eastern France, November 1944 was turning from mud to frost. Inside, under bad light and worse coffee, a different kind of weather system was forming over paper.

Maps covered everything.

They lay across sawhorse tables, pinned to rough plaster, clipped to stands. Thick blue arrows marked Third Army’s spearheads driving toward the German border. Thin red symbols showed known enemy formations, like dried blood spots on an old bandage. Dotted chains traced supply routes and phase lines, those delicate lifelines that turned fuel and food into movement and victory.

The room smelled of cigarette smoke and wet wool drying near a little iron stove. The air hummed with the low, constant murmur of staff officers doing what staff officers do—writing, erasing, calculating, re-checking.

At the center of it all, like a storm in human form, stood George S. Patton.

Fifty-nine years old, lean as a blade, he hovered over the main map table, fingers splayed on paper Europe as if he could push the blue arrows forward by hand. Light from a naked bulb caught in the polished curve of his helmet and the ivory-handled pistols at his hips. His voice, when he spoke, cut through every other sound—sharp, impatient, driven by a single direction:

East.

He wanted Germany. He wanted to kick the door in and keep going until there was nothing left to shoot at. He wanted, God help him, to end the war by Christmas.

“Forward,” he snapped to nobody in particular, tapping the map near the German border. “We keep hitting them here, here, and here. Don’t give the sons of bitches time to dig in. We press. We don’t stop.”

Around him, officers nodded, made notes, traded quick glances. They knew the general’s mood. Patton in November 1944 was a man in a hurry. The papers back home called him “Old Blood and Guts.” The GIs had their own version of that nickname, more cynical, but even they couldn’t deny the simple truth: when Patton’s columns moved, the front moved with them.

In one corner of the war room, away from the noise and the swagger, a man sat at a smaller desk.

He did not look like a man about to alter the course of a battle that hadn’t started yet.

Colonel Oscar Koch—Patton’s G-2, his chief intelligence officer—was a thin, precise figure in wire-rimmed glasses and a uniform that somehow always looked neat even when everyone else was leaking mud. His corner was crowded not with maps of sweeping arrows but with paper: typed summaries, prisoner interrogation transcripts, radio intercepts, aerial reconnaissance photos, unit identification logs, logistics reports.

Koch’s battlefield was sentences and numbers, dots on film and rumors that might be nothing—or everything.

He turned another page, tapped his pencil twice against the edge of the desk, and frowned.

Something was wrong.

Not in a dramatic, cinematic way. There was no single captured document titled “Hitler’s Last Gamble,” no prisoner who blurted out the entire plan. Intelligence work almost never handed you answers in one piece.

It was in the little things.

A prisoner from a Volksgrenadier division, picked up in a skirmish, insisting his unit had been refitted and sent west. Except, according to official Allied records, that division was supposed to be spent, scattered, or on the Eastern Front.

Radio intercepts—short, tight bursts of German signals traffic—spiking in sectors that, on paper, held only worn-out enemy remnants.

Aerial photographs showing rail yards in western Germany far busier than they should have been, trains moving west instead of east. Tank transporters. Covered wagons.

Logistics reports: signs of fuel and ammunition being stockpiled near the Ardennes, that forested, hilly region between Belgium and Germany where the American line was thin, held by tired infantry divisions on what everyone liked to call “a quiet sector.”

None of it, taken alone, screamed disaster.

Taken together, it formed a pattern, the way a handful of stars suddenly become a constellation once someone draws the lines.

Koch had trained himself over years to see those lines.

He’d learned—North Africa, Sicily, France—that the most dangerous phrase in any headquarters wasn’t “we’re outnumbered.” It was “they can’t possibly.”

Can’t possibly attack there.

Can’t possibly have that many tanks left.

Can’t possibly be that foolish, that bold, that desperate.

The enemy always could. The enemy sometimes did. And when they did, men died because someone had chosen comfort over accuracy.

Koch put down his pencil and reached for a fresh map.

He began to mark it.

Here, a newly identified regiment. There, a logistics dump where nothing should have been. Here, increased radio traffic. There, railway movement. A sprinkling of dots and arrows, each small on its own. Then he stepped back.

On the paper, the westward shift of German strength looked like a shadow creeping toward the Ardennes.

His stomach tightened. He took off his glasses, rubbed the bridge of his nose, and for a moment simply listened to the murmur of the war room—the general’s bark, the clatter of cups in a corner, the scratch of pens.

They had been fighting for months, and the talk, officially and unofficially, was that the war was nearly done.

Germany was running out of fuel. Her armies were shattered. Her cities were in ruins. Every intelligence estimate from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force—SHAEF—painted the same picture: the Wehrmacht in the West was a spent force, capable of only limited local counterattacks.

And yet…

Yet the enemy was bringing divisions west. Yet the shells were being stacked. Yet the roads in the wrong places were being repaired in the snow.

Koch’s job was not to snap to the prevailing mood like a flag in the wind. His job was to say, quietly and clearly, what the evidence showed—even if nobody wanted to hear it.

He reassembled his papers into a lean stack. He checked his notes one more time. Then he pushed back his chair and stood.

The decision weighed more than his rank.

He crossed the war room, feeling the quick sideways glances of junior officers who barely knew his name. To them, he was just another colonel in a headquarters full of colonels. They saw Patton when they looked at history.

Koch knew better. History was made as often at the margins of maps as at the center of them.

He reached the big table.

“Sir,” he said.

Patton didn’t turn at once. He traced a finger along a blue arrow pushing toward Saarbrücken, lips moving around thoughts he didn’t say out loud.

“Sir,” Koch repeated, a little louder but still calm.

Patton straightened and looked at him. The general’s eyes were a startling blue, bright with impatience and something else—a kind of hungry curiosity. For all his bluster, he liked information. He liked to know.

“Yes, Oscar?” he said, and just the fact that he used the first name told everyone else in the room to shut up and listen.

Koch set the stack of reports down and placed his hand on the corner of the main map, near the Ardennes.

“I believe the Germans are preparing a major counteroffensive,” he said, his voice steady. “Possibly through the Ardennes. Soon.”

The room went still.

Someone near the stove gave a short, nervous laugh that died fast.

One of the operations officers shook his head faintly, as if brushing away a fly.

The Ardennes? That was the “ghost front,” the place you sent worn-out divisions to rest, refit, and curse the winter weather. Forests, hills, bad roads, lousy tank country. The idea of a major German offensive there, in winter, with American armies already on German soil and the Luftwaffe all but broken… it sounded like an anxiety dream, not a staff briefing.

But Patton did not laugh.

He leaned over the map, hands on either side of the Ardennes sector, and said simply, “Show me.”

Koch began to talk.

He was not a dramatic speaker. There were no sweeping gestures, no table-pounding. He took Patton through it piece by piece—prisoner reports, radio intercepts, aerial photos, logistics summaries. He pointed out divisions that were supposed to be elsewhere but had been identified near the Ardennes. He pointed to rail lines that had suddenly grown busy. He noted that the sectors opposite the thin American line had gone quiet—too quiet.

He explained, as he always did, in terms of capability, not crystal-ball predictions.

“The question isn’t whether Hitler is crazy enough to try something,” Koch said. “We know he is. The question is: can he? Does he have enough men, tanks, artillery, and fuel to mount one more large operation?”

He tapped the pattern of symbols with a knuckle.

“Based on what we’re seeing,” he said, “I believe the answer is yes. He can mass enough force for a substantial blow. A winter offensive aimed at splitting our armies, perhaps driving to the coast, is within his capabilities.”

He straightened.

“I cannot tell you exactly when,” he added. “I cannot give you an attack hour. But I can tell you the conditions are favorable. Weather that could ground our air support. A weak section of our line. Enemy movement into that sector. Sir, in my judgment, a major attack through the Ardennes is a significant risk.”

He stopped there.

The war room felt even smaller than before. The only sounds were the creak of the stove and someone clearing a throat in the back.

An operations officer spoke up, careful but dismissive.

“General, with respect, G-2 may be overinterpreting limited data,” he said. “SHAEF headquarters does not share this assessment. Their latest estimate says the Germans are incapable of sustained offensive operations in the West. These could be spoiling attacks at most.”

Another officer chimed in, “We’ve been moving so fast they’re bound to try something local. But a major attack? Through the Ardennes? In winter? It doesn’t make sense, sir.”

Patton raised one hand.

The objections dried up.

He turned his head, looked at Koch, and asked the only question that mattered.

“How sure are you?”

Koch did not pretend.

“I can’t be certain,” he said. “Intelligence never is. But the capability is there, and the indicators are pulling in the same direction. In my professional judgment, the risk is real.”

Patton stared at the map, jaw working.

He lived for aggression. His whole theory of war boiled down to movement, shock, speed. He believed hesitation cost more lives than boldness. The correct instinct, as he saw it, was always to attack.

But this—this was about being attacked.

“Let’s say you’re wrong,” he said slowly. “Let’s say this is smoke and noise and nothing comes of it.”

He glanced around at the faces watching him.

“What do we lose if we prepare?” he asked.

“Staff time. Some fuel on contingency planning,” Koch replied. “We’d draw up movement orders we might never execute.”

“And if you’re right,” Patton said, eyes back on the Ardennes, “and we do nothing?”

Koch didn’t look at the map when he answered. He’d been looking at that future in his head for days.

“Then we lose men,” he said. “A lot of them.”

The silence that followed wasn’t confusion.

It was a choice forming.

Patton’s fingers drummed once on the table. Then he nodded, a sharp, decisive motion.

“All right,” he said. “Draw up contingency plans. If the Germans hit the Ardennes, I want Third Army ready to pivot north and strike into their flank. Not in a damn week. In days. In hours, if we can manage it.”

Several staff officers blinked, as if the general had just suggested they turn the moon.

“Sir, an army-sized ninety-degree turn in winter…” one of them began.

“Get it done,” Patton snapped. “That’s not a suggestion. That’s an order. Fuel, routes, assembly areas. I want it all on paper. When those Krauts stick their necks out, I want to be in position to cut the bastards’ heads off.”

He looked back at Koch.

“And Oscar?”

“Yes, sir?”

“Good work,” Patton said. “I’d rather look like a fool for preparing than a murderer for being surprised.”

Koch just nodded.

That was all he’d wanted—to be heard.

The days that followed didn’t feel like anything was about to explode.

Winter thickened its grip. The more obvious enemy was the weather.

Convoys slipped on ice. Engines coughed to life in the morning like old men clearing their throats. At Third Army headquarters, typewriters clacked late into the night as operations officers did what Patton had demanded: they bent the entire east-facing geometry of the army into hypothetical northward arrows.

They identified units that could be pulled out of line quickly. They calculated how much fuel three armored and infantry divisions would need to march a hundred miles in snow on short notice. They marked assembly areas, checked bridges, traced possible routes through towns whose names nobody had paid much attention to until suddenly they mattered.

Many of them thought it was an exercise.

Patton was known for demanding the improbable. He liked to ask for things nobody else believed could be done, then watch his men scramble and, more often than not, do them. This might be just another churn of the Patton machine: build a plan, never use it, file it away alongside a dozen other wild schemes.

But the plan was written.

And the calendar rolled toward December.

In the early hours of December 16, 1944, the forest woke up.

Along an eighty-mile stretch of the Ardennes front, German artillery opened up with a suddenness and ferocity that felt, to the men on the receiving end, like the sky itself was cracking.

Shells screamed down into thinly held American positions—foxholes dug in hard, frozen ground, command posts nestled in little Belgian villages lit by Christmas candles, supply dumps, road junctions. Communications lines snapped like twigs. Trees exploded, sending splinters and snow and shrapnel in every direction. Entire companies were shredded before they understood they were in a battle.

Then the infantry came.

In the darkness and fog that clung to the hills, German Volksgrenadiers and paratroopers moved forward behind the barrage. Tanks and assault guns rumbled along narrow roads. Skies too low and thick for Allied fighter-bombers gave them cover.

They hit the seams—those points on any front where one American division’s sector ended and another’s began, always a little softer, always a little fuzzier than a map line suggested.

They also hit units on “quiet” duty—tired divisions spread thin, meant to be resting after earlier fights, men who’d been told this was where you waited out the winter with a little luck and a lot of boredom.

By midday, the front in the Ardennes was no longer a line.

It was a set of question marks.

Reports began to pour into SHAEF like cold water into a ship.

Enemy breakthrough at LXXX.

Enemy armor sighted near XXX.

Unit cut off.

Unit overrun.

Command post lost.

Radio out.

Request instructions.

At Supreme Headquarters, where official estimates had insisted Germany lacked the strength for precisely this kind of operation, the reaction was shock shading into disbelief.

This wasn’t a spoiling attack. This wasn’t a local counterblow to tidy up a salient.

This was a full-scale offensive—the biggest German attack in the West since 1940.

Later, historians would call it an intelligence failure.

But where Patton stood, back in that war room whose maps he’d already had redrawn with northward arrows, nobody shouted.

Koch spread the fresh reports beside his old markers and watched the enemy do what he had expected them to do.

There was no satisfaction in it. No “I told you so” to be savored.

There were too many men in too much trouble for that.

He went to Patton.

“They’ve hit the Ardennes,” he said, voice as quiet as ever. “On a broad front.”

Patton didn’t ask how it was possible.

He asked, “How bad?”

“Bad,” Koch answered. “They’ve punched a deep hole. Units are cut off. The road net is congested. They’re driving for key junctions. If they reach the Meuse in strength…”

He didn’t finish the sentence. He didn’t need to.

Patton had read the same maps, drawn his own arrows. He knew as well as any German planner what such an offensive could do if it went unchecked.

He picked up the phone.

Eisenhower’s staff, several steps removed from the panic in the foxholes but close enough now to feel the outlines of catastrophe, were already scrambling to patch together a response. They were talking about reserves, about moving British units, about shifting air assets if the weather cleared.

Then Patton’s gravelly voice cut onto the line.

“This is Patton,” he said. “I can disengage part of Third Army from our current front and turn north into the German flank.”

There was a pause. Someone on the other end—Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, or Eisenhower himself—asked the question.

“How soon?”

Patton hardly hesitated.

“Forty-eight hours,” he said. “Three divisions.”

The thing hung there in the line hum.

Armies didn’t move like that.

They were vast organisms of metal and flesh and fragile roads. They required planning, fuel, bridges, traffic control. They took time to unstick from one battle and march toward another.

“You mean you can start in forty-eight hours,” someone said.

“No,” Patton snapped. “I mean I can be attacking in forty-eight hours. We’ve already done the planning. All I need is the word.”

He got it.

And the plan in the drawer—the one most of his staff had quietly assumed would stay there—became reality.

If you were a private in one of those divisions, you didn’t see the planning.

You saw a sergeant shaking you awake in the dark.

You’d been hoping, maybe, for a few nights in a barn without artillery. You’d been thinking about coffee that didn’t taste like boiled mud, about clean socks, about Christmas somewhere that didn’t smell like cordite.

Instead, you got orders.

“Pack it up. We’re moving.”

“Where?”

“North.”

“Why?”

The sergeant shrugged. “They’ll tell us when we get there.”

You climbed into the back of a truck with your rifle and your pack and your friends, the canvas flaps snapping in the wind.

The cold was a living thing.

It crawled through gloves, bit at cheeks, turned breath into frost on the inside of the canvas. The trucks’ engines growled and whined, tires slipping on ice and packed snow. Headlights stayed off; blackout discipline turned the convoy into a ghost snake stretching for miles, guided by cat’s eyes on the roadside and the dim shapes of the vehicles ahead.

The road signs—when you could see them—had names that meant nothing.

Bastogne. Ettelbruck. Longvilly.

You didn’t know that somewhere ahead, men of the 101st Airborne and other units were dug into frozen foxholes around Bastogne, surrounded, outnumbered, shells coming in day and night. You didn’t know that German tanks were stalled on roads because of fuel shortages and traffic jams, buying you precious hours. You didn’t know that two weeks earlier, a quiet colonel in a headquarters you’d never see had stared at a map until his eyes hurt and decided this would happen.

You just knew you were moving. That was enough.

Men dozed sitting upright, heads bumping against wooden slats, waking with curses when the truck hit a rut.

Drivers hunched over wheels, feeling the road as much as seeing it, coaxing their vehicles around curves that suddenly held sheer drops into blackness.

Tanks rode transporters, clanking and groaning, or crawled under their own power, treads squealing on ice. Fuel trucks spent as much time getting pulled out of ditches as they did moving forward. Engineers sweated under layers of wool and steel as they threw up makeshift bridges over streams and repaired blown culverts.

Nobody had to tell them why this mattered.

Somewhere in the snow, Americans were cut off.

That was reason enough.

It was brutal, exhausting, miserable.

But it worked.

In less than three days, Third Army swung ninety degrees and drove more than a hundred miles through winter to smash into the southern flank of Hitler’s last gamble.

On December 26th, lead elements of Patton’s columns broke through to Bastogne.

For the men inside that Belgian town— paratroopers who’d been told they were on rest, clerks handed rifles, tankers whose vehicles had been picked off one by one—the sound of those engines coming up the road was like hearing the future arrive.

Relief didn’t look like angels.

It looked like Shermans and half-tracks grinding through snow, like tired men in different patches but the same flag climbing out of trucks to say, “Merry Christmas, you lucky bastards. Thought we’d join the party.”

For the Germans, the party was over.

The offensive that had bulged the Allied line fifty miles deep began to collapse under pressure from north, south, and west. Fuel shortages, traffic logjams, and the simple reality of American numbers and air power—once the weather cleared—chewed away at their advance.

By late January, the bulge was gone from the map.

On the ground, it was gone in a different way—reduced to wreckage, frozen bodies, spent shells, and stories that would echo for the rest of men’s lives.

Germany had thrown in tanks, men, and fuel she could never replace. The war in Europe still had months of killing left in it, but its outcome was no longer a serious question.

A lot of men came out of that winter alive who otherwise would not have.

They owed their survival to paratroopers who refused to surrender, to tank crews who held crossroads, to riflemen who dug in deeper when everything in them wanted to run.

And also—to something they’d never see.

A conversation in a war room between a loud general and a quiet analyst.

Oscar Koch didn’t appear in the newspaper photographs of the relief of Bastogne.

He wasn’t on the hood of a jeep surrounded by cheering paratroopers. He didn’t pin medals on anyone. He didn’t give speeches.

He was in that same cramped corner of Third Army headquarters, glasses low on his nose, pencil in hand, tracking the shrinking red symbols on his maps as the German units bleeding themselves out in the snow tried and failed to salvage their offensive.

After the war, when historians and commissions and Monday-morning quarterbacks turned their attention to the Battle of the Bulge, they asked the obvious question:

How did we miss this?

How did Allied intelligence, with its codebreakers and reconnaissance planes and interrogators, fail to predict a German offensive that took thousands of lives and nearly split the front?

Reports were written.

Charts were drawn.

“Intelligence failure,” they called it.

Koch knew that wasn’t the whole story.

The information had been there.

The signs were visible—to anyone willing to look across their own assumptions.

The failure was not just in collection. It was in evaluation, in belief, in the willingness to act on an uncomfortable possibility.

The difference between disaster and catastrophe, this time, lay in the fact that one commander had listened.

George Patton was, by any measure, a loud man. He believed in reincarnation, in destiny, in slapping sense into soldiers who showed fear. He swore like a sergeant major and quoted the Bible and Napoleon in the same breath. He loved war in the way only someone who’d studied it his entire life and still believed it was the ultimate test could love it.

But when his intelligence officer told him a story that didn’t fit his plans, he didn’t shout him down.

He asked, “How sure are you?”

He weighed the cost of overpreparing against the cost of being wrong.

And he chose to prepare.

That choice—made in a smoky room over a piece of paper—turned into fuel allocations, truck convoys, and men in frozen trucks heading north in the dark.

After the war ended, Patton’s legend grew even larger. The films and books focused on the obvious things—his speeches, his temper, his dash across France, his controversial statements.

He died in December 1945 in a car accident in Germany, months after the guns fell silent. He was buried among his men, as he would have wanted.

Oscar Koch lived a quieter life.

He retired from the Army. In the late 1960s, he worked with journalist Robert Allen to write a book: G-2: Intelligence for Patton. In it, he laid out his view of those campaigns—North Africa, Sicily, France, and, yes, the weeks before the Bulge. He explained his methods, his insistence on counting enemy capabilities rather than simply assuming enemy intentions. He explained how he’d put together the clues and gone to Patton with a warning.

People called him “Patton’s oracle.”

He didn’t like that.

He didn’t see himself as a prophet.

He saw himself as a man who’d done his job: looking at evidence, judging enemy capabilities honestly, and telling his commander what the numbers said, not what anyone wanted them to say.

In his private reflections, he circled back to the same point.

The tragedy, he thought, was not that intelligence officers failed to see the German buildup.

It was that so few commanders were willing to listen.

Patton, for all his flaws, was the exception.

If this story ended in January 1945, it would be tidy enough.

But stories like this don’t really end.

They repeat.

Not with maps and artillery, necessarily. Not with tanks sliding on Belgian ice or paratroopers in foxholes.

They repeat in quieter rooms.

In boardrooms, where executives stand over financial charts like Patton over his maps, eyes on blue arrows of projected growth, red symbols of competition. In corners of those rooms, analysts sit with spreadsheets and models and quiet frowns, seeing patterns in the numbers: product lines that are failing, risks that are rising, markets that are shifting.

“Sir,” they say. “I believe we’re headed for trouble.”

In families, where one person sees what nobody wants to talk about—a drinking problem, a child’s distress, a marriage fraying under the weight of silence—and clears their throat at a dinner table suddenly too quiet.

“We need to talk,” they say. “Something’s wrong.”

In hospitals, where a nurse notices a subtle change in a patient’s breathing, a lab tech spots an odd result, a junior doctor questions a diagnosis that doesn’t fit the evidence.

“Wait,” they say. “This doesn’t add up.”

Everywhere decisions are made, there are loud voices and quiet ones.

The loud ones drive forward. They set goals, make plans, draw arrows. They believe, as Patton did, that momentum is life.

The quiet ones sift through the debris of reality and say, “Something’s off.”

Wars, companies, families, entire futures turn on what happens next.

Do the loud listen?

Or do they wave it off because the timing is bad, because higher headquarters doesn’t share that assessment, because the idea of catastrophe is simply too uncomfortable to fit into the story they’re telling themselves?

George Patton was a great general for a lot of reasons.

But maybe his greatest single act was not a bold attack or a vulgar speech.

Maybe it was the moment he looked at a quiet colonel with a stack of reports and made the calculation out loud:

“If you’re right and we do nothing, we lose men. If you’re wrong and we prepare, we lose time and effort.”

And then said, “Draw up the plans.”

Oscar Koch’s legacy is not in statues.

It’s in all the men who walked out of the Ardennes alive, who went home, who married, raised kids, grew old. It’s in the ripple effect of thousands of lives not cut short in a forest because one analyst refused to let wishful thinking overwrite what the evidence said.

When the story of the Bulge is told purely as an intelligence failure, it misses that.

There was also an intelligence success—not in predicting the exact hour of the attack, but in seeing the storm coming and convincing one man in the right place to put up sandbags before the first drops fell.

Somewhere today, there’s a quiet voice in a corner of your life doing something similar.

Seeing a pattern you’d rather not see.

Pointing at a map you’d rather not redraw.

Telling you that the comfortable story—“the war is almost over, the enemy is finished, we just have to grind forward”—isn’t the whole truth.

You may be the Patton in that situation, or you may be the Koch.

If you’re the quiet one, the lesson is to speak anyway. To clear your throat in the smoky room and say, “Sir, I believe…”

To risk being wrong, or ignored, in order to avoid being right too late.

If you’re the loud one, the leader, the parent, the boss, the person at the head of the table, the lesson is harder.

It’s to recognize that courage doesn’t only look like charging forward.

Sometimes it looks like stopping. Turning. Admitting that you might be heading the wrong way. Ordering an entire army—real or metaphorical—to pivot north in the snow based on the possibility that the worst-case scenario might be true.

Thousands of men trudged out of a winter forest in 1945 because a loud man listened to a quiet one.

That’s not ancient history.

That’s a pattern.

The maps change. The stakes look different. The uniforms are gone.

But the question this story leaves behind is simple and sharp as a winter wind:

When the quiet analyst in the corner says, “I think danger is coming,” will you be the one who laughs—or the one who leans over the map and says:

“Show me.”

THE END

News

CH2 – Japanese Officer’s Final Note: “Black Montford Marines Made Victory Impossible”

General Tadamichi Kuribayashi did not believe in miracles. By the time he stood on the volcanic rock of Iwo…

CH2 – American Soldiers Were Shocked by the Beauty of Italian Women During the Liberation

They’d heard about Italy long before they ever saw it. In North Africa, when the nights cooled off enough…

CH2 – The Simple Trick One Unknown Pilot Used to Shoot Down 6 Messerschmitts in a Single Day

By the time the war reached its third summer, the sky above Europe had become a kind of machine. Engines,…

CH2 – They Banned His “Upside Down” Radio Wire — Until It Saved an Entire Convoy from U Boats

By the time the war reached its third summer, the sky above Europe had become a kind of machine. Engines,…

CH2 – They Laughed at One Pilot’s “Crash the Runway” — Until He Blocked the Luftwaffe’s Take Off

February 9, 1944. Northern France. The airfield near Bovet lay under a low sheet of frozen mist, as if someone…

CH2 – When 2,700 Japanese Attacked 33 Marines — This Sergeant’s 10-Hour Stand Left Everyone Speechless

At 2:00 a.m. on October 26th, 1942, Platoon Sergeant Mitchell Paige crouched behind a Browning M1917 water-cooled machine gun on…

End of content

No more pages to load