Night pressed down on the French woodland like a wet wool blanket.

Fog drifted low across the forest floor, a thin, pale current that curled around shattered trunks and jagged stumps. The trees had once been tall and proud; now they stood as blackened spears, blasted by artillery, their branches sheared off like limbs. Somewhere in the distance, a shell rumbled, its echo a slow, hollow boom rolling through the mist.

Captain Arthur Hail moved forward one measured step at a time.

He was thirty-one, British Army—uniform darkened by damp, helmet rim slick with cold sweat and mist. His leather gloves were wet. The cold had crept through the seams of his greatcoat hours ago; now it gnawed at his shoulders and spine, settling somewhere behind his sternum like a stone.

His men fanned out behind him, ghosts in khaki, boots sinking silently into the spongy ground. The only sounds were the soft shuffle of gear and the occasional muted sniffle against the cold.

“Sir,” one of them whispered. “You hear that?”

Hail raised a fist.

They froze as one. Boots stopped mid-step. A breath caught in the dark.

Then he heard it.

A sound that did not belong to wind or artillery or the distant clank of armor—a thin, rasping noise, almost like someone dragging sandpaper over wood. Almost like breathing. Almost like…pleading.

“Hold,” he murmured. His voice was low, but in the quiet, it carried.

They waited.

The sound came again.

Hail signaled with two fingers, moving forward alone. The men stayed back, rifles up, watching his silhouette slide into the open space ahead.

The clearing looked wrong.

Artillery had chewed up most of the undergrowth. A single wooden post stood near the center, half-charred, leaning slightly, surrounded by the ghosts of what had once been an outpost—splintered planks, twisted wire, an overturned crate with German letters burned into its side.

Ropes hung from the post like dead vines.

Something—no, someone—was slumped against it.

Hail’s heart kicked once, hard.

He stepped closer, boots squelching in the mud. The smell hit him next: pine needles crushed underfoot, smoke from burnt timber, a faint copper edge of blood gone stale.

It was a woman.

She was bound against the post, arms drawn behind her, wrists lashed so tight the rope had cut skin. Her ankles were tied together, and the coarse hemp had sliced through socks and into flesh. Her uniform, once crisp medical white, hung in grimy tatters. A heavy winter coat had been thrown over her shoulders, half slid off one side to reveal a bruised collarbone and a patch of clammy, exposed skin.

Her hair had been braided at some point, neat and orderly, the way nurses wore it. Now it was tangled with dead leaves and mud, stray strands glued to her cheek by dried blood. From her temple to her jaw, a dark streak marked where something—rifle butt? fist? stone?—had torn skin.

Around her neck hung a wooden sign, crudely cut, the letters gouged in with something sharp and angry.

Verräterin.

Traitor.

Hail felt his throat tighten. He’d seen plenty of dead and dying men in this war—British, German, French, anonymous bodies that no longer belonged to anyone. But there was something about the stillness of this woman’s figure, the way her head drooped forward, the rope biting into her pale wrists, that twisted deeper than the usual dull numbness.

“Captain?” one of his men whispered from the tree line. “Sir, what do you see?”

Hail didn’t answer.

The wind shifted. The woman’s head lolled to one side.

Her eyes fluttered open.

They were startlingly blue, ringed with red veins of exhaustion. For a second, she looked straight through him, pupils unfocused, like someone surfacing from deep underwater and not yet noticing the sky. Then her gaze locked onto his face, onto the shape of his helmet, the foreign cut of his uniform.

Her lips moved.

“Bitte…” Her voice cracked, then she tried again in halting, accented English. “Please. Don’t shoot.”

The sound of it—a plea so raw, so small—cut through the cold and the fog and the distance between them more sharply than any bullet.

Hail stepped forward, slowly, hands visible.

“Easy,” he said quietly. “You’re safe now.”

The words felt flimsy, almost dishonest under the circumstances. Safety, out here, in this shredded corner of France, was always temporary.

But her breath hitched anyway. Relief and disbelief tangled in her chest, visible even under the heavy coat.

Behind him, a twig snapped. One of his men shifted, boot slipping a fraction.

The Germans were gone—the abandoned post, the burned supplies, the sign around her neck all pointed to a hasty withdrawal. They could have shot her. They hadn’t. Instead, they’d tied her here, a message to whoever found her: this is what we do to our own when they break.

It could’ve been a trap.

It wasn’t.

Hail saw enough fear in her eyes to know this wasn’t performance.

“Cut her down,” he ordered.

Two men broke cover, staying low, rifles still half raised just in case. They saw her clearly now—a German nurse, uniform white under the grime, coat standard Wehrmacht issue. The sign around her neck rocked slightly as she breathed.

Private Jacobs hesitated a half-second before putting his bayonet to the rope.

“Sir,” he muttered, “you sure about—”

“Cut her down,” Hail repeated, more quietly this time. “That’s an order.”

The rope parted with a rough snap. Tension vanished from her body all at once. Her legs, long past numb, buckled. She crumpled like sent cloth.

Hail caught her by instinct.

She weighed almost nothing. Under the coat and dirty dress, her frame felt all bone and angle. Hunger had been carving at her for months; he could tell that just by the way her shoulder fit into his hand, sharp and fragile.

Her head tipped against his chest for a heartbeat.

“Name?” he asked, because regulation clung to him like his wet coat, even here.

She swallowed, throat working, words slow. “Leisel…Brandt,” she managed. “Krankenschwester. Field nurse.”

Her English hung on the German syllables.

He nodded. “Leisel,” he repeated. “We’re taking you out of here.”

She flinched at the word taking, but didn’t resist. She didn’t have the strength to.

They moved her to the truck.

The ride back to the British lines was a slow, swaying journey through black trees and deeper fog. The engine hummed low; the canvas cover flapped with every bump.

Leisel sat pressed against the wooden wall of the truck bed, coat pulled tight. Every jolt made her wince. She had the look of someone who’d spent too long bracing for impact—muscles coiled even in rest, eyes snapping to every noise.

Hail sat across from her, boots planted, holding onto a strap to keep from sliding as they hit ruts.

He handed her a canteen.

She stared at it like it might bite.

“It’s just water,” he said.

She hesitated another second—conditioning battling instinct—then took it with both hands. Her fingers shook so violently the metal rattled. She brought it to her lips and drank in cautious, tiny sips, as if expecting the taste to turn sour at any second.

The soldier next to Hail leaned in and muttered under his breath, “Looks like she hasn’t seen a proper drink in days, sir.”

Hail didn’t respond. He could see it for himself.

When she finally lowered the canteen, a small line of water traced her chin. She wiped it away self-consciously, eyes already darting toward the truck’s opening, as if counting trees, memorizing route, searching for ways to escape or attack.

She was here, but her mind was still somewhere between no-man’s land and a German ward full of wounded boys.

A small leather book had slipped out of her pocket when they’d lifted her into the truck.

Jacobs picked it up, turned it over, and handed it to Hail. “Found this, sir.”

A diary.

It felt like an intrusion. It also might be their only glimpse into the twisted logic that had left her tied to a post with the word traitor around her neck.

Hail opened it carefully.

The pages were packed with cramped handwriting, ink pressed hard into paper. Some lines were smudged, as if written in a hurry or with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking. Others were stained with something brownish-red.

He skimmed.

The officers say retreat is treason. Anyone who speaks of surrender is enemy to the Reich. Today, three nurses were taken for questioning. They did not return.

He turned the page.

We heard Allied leaflets say: “Captured nurses are treated well.” Lies. They want us to surrender like cowards.

Another entry.

I told the doctor I saw children dead in the snow. He said, “Compassion is weakness.” Perhaps I am weak.

The last one was short, words sloping down as if written while standing or running.

They know. They know I helped the wounded villagers. God forgive me.

Hail closed the book slowly.

He looked up at Leisel.

Her eyes were fixed on the diary in his hand, pupils huge and scared.

“Why?” he asked quietly. “Why did they do this to you?”

She flinched, then pulled her coat tighter, as if she could stuff the answer back inside herself.

“I…” Her voice wavered. “I gave bandages to…French child. Villagers. Not soldiers.” She swallowed. “Doctor say…helping enemy. Say I…betray Fatherland.”

Her lips trembled around the last word.

“Betrayal,” Jacobs scoffed under his breath. “For bandages.”

Hail shot him a look that shut him up.

Outside, the artillery finally quieted. For a brief moment, the only sound was the engine and the faint rattle of something in the truck bed.

Inside, a different war—quieter, uglier—lingered around the edges of the canvas.

The British field camp bloomed out of the night like a small, stubborn island of warmth.

Lanterns hung from tent poles, their light golden against canvas walls. Medical tents stood in orderly rows, guy lines crisscrossing. Fires burned in steel drums, men huddled around them for smoke and comfort.

They took Leisel straight to the medical tent, not to a cage.

That alone seemed to confuse her.

She stiffened the moment they crossed the threshold, shoulders drawing up under the weight of the coat. The smell inside—a mix of disinfectant, sweat, iodine, and boiled wool—was familiar. The layout of the cots, the low shelves of supplies, the clink of sterilized metal—these were her world.

The uniforms were not.

She moved instinctively toward the edge of the room, not trusting the open space. Hail guided her gently to an empty cot, but she perched on the very edge of it, feet drawn under, like a bird ready to bolt.

A British medic—a corporal with round glasses and ink stains on his fingers—approached with a basin and a roll of bandages.

“Name’s Thompson,” he said softly, voice carrying the lilting edges of Manchester. “I’m going to check those wrists, all right?”

Leisel’s entire body recoiled.

She slammed back into the cot frame, eyes wide, breath a fast, shallow flutter. Hands went up reflexively, as far as the torn skin would allow, as if to block a blow.

Hail came around, dropping to one knee beside her.

“It’s all right,” he said. “He’s a medic. Like you.”

“Interrogation?” she whispered. The word came out raw. “Questions?”

“No interrogations,” Hail said, meeting her gaze. “Not tonight. Just treatment.”

She blinked, disoriented. This did not match anything she’d been told.

Thompson moved slowly, telegraphing every step.

“May I?” he asked, reaching toward her wrist.

She nodded once, jerky, like someone giving permission under duress. But she didn’t pull away this time.

He lifted her arm with the kind of care reserved for rare porcelain. The rope had burned deep grooves into her skin, edges darkened, flesh swollen and angry. He cleaned the wounds with warm saline, his touch steady, not careless or punishing. She winced, but he murmured apologies she didn’t understand and wrapped soft gauze around her wrists, then her ankles.

No shouting.

No slap when she flinched.

No sneered words about weakness.

Just hands doing their work.

“Warum?” she whispered finally, the German slipping out before she could catch it. “Why…kind?”

Hail answered in English, keeping his tone low.

“Because you’re a human being,” he said simply.

Her gaze flickered away, tears prickling at the edges.

She had been told the enemy were monsters.

It was easier to hate monsters.

Monsters didn’t wipe mud off your face with a clean cloth.

Monsters didn’t tuck blankets around your shoulders.

The first meal nearly broke her.

It was nothing fancy by British ration standards—a bowl of vegetable stew, thick with carrots and potato and barley; a hunk of bread still warm from the makeshift camp oven; a tin mug of tea that steamed in the cool tent air.

She sat up slowly, blanket wrapped around her shoulders, watching as Thompson placed the bowl on the crate beside her bed.

“Here you are, miss,” he said. “Careful, it’s hot.”

She stared.

She stared so long that Hail, sitting on a stool nearby with his own chipped mug, finally said, “Is there a problem?”

“In…Germany,” she said without looking up, “sugar…is for officers only.”

She lifted the mug to her lips.

The tea was sweetened. Not by much—a single lump, maybe—but enough for the unexpected taste to wash over her tongue and drag something up from the back of her throat that felt suspiciously like a sob.

She swallowed it down.

Her hands shook so hard she almost spilled the stew.

She began eating slowly, mechanically.

Then faster.

Then with a desperate edge, as if the food might vanish mid-bite.

No one stopped her. No one reached for her bowl halfway through and told her she’d had enough.

A private with freckles walked by, saw her shivering despite the blanket, and unwound his scarf without comment. He laid it beside her cot.

“If you need anything, miss,” he said softly, “just holler. We’re not far.”

She couldn’t meet his eyes.

Kindness was a sharper weapon than any blade. It slipped past armor propaganda had built and cut directly into the soft, unprotected parts.

That night, she lay under layers of wool, listening to the muted camp noises—the distant laughter around a fire, someone tuning a harmonica, a low curse as someone tripped on a tent guy line.

She couldn’t sleep.

Her body was warm. Her stomach was full. Her wounds no longer burned. But her mind replayed the sounds of Dresden under siren wail, of children crying in basements, of officers barking orders with spittle at the corners of their mouths.

Her diary lay on the crate beside her. She reached for it, fingers trembling.

She wrote by lantern light, cramped script digging into the paper:

They look at me, not with hatred or disgust, but with something worse. Pity. As if I am the one abandoned. As if Germany left me on that post long before the rope burned my skin.

She paused, pen hovering.

Are they lying?

She didn’t know anymore.

Hail didn’t spend every waking moment near the medical tent. He still had a company to run, patrols to coordinate, maps to study. But he found himself drifting back more often than not, under the pretense of checking on the wounded.

He’d always believed in war as a series of choices in inconvenient circumstances. You did what had to be done, you lived with it, you moved on. There was no space in that calculus for mercy beyond what regulations allowed.

But Leisel complicated the math.

He’d seen German POWs before—some defiant, some broken, some just tired. He had a certain compartment for them in his head.

She did not fit.

She spent the first few days curled inward, eyes tracking every movement, body primed for invisible blows. When someone laughed, even gently, she flinched. When a door flap snapped in the wind, she jerked, heart racing.

Then, slowly, something shifted.

It happened the first time a British nurse—Captain Claire Adams, all crisp efficiency and sharp tongue—dumped a tray of bandages at the foot of Leisel’s bed.

“You’re wasting perfectly good skills sitting there like a ghost,” Claire said briskly. “Either you help, or you get out of my tent.”

Leisel stared. The words were harsh, but Claire’s eyes were kind. Frustrated, but kind.

“I…” Leisel glanced at Hail, as if seeking permission.

He shrugged. “Up to you.”

Her fingers twitched.

Work was safe. Work was familiar. Work meant she didn’t have to think.

She slid off the cot.

Her ankles protested, but she ignored them. She took the bandages, began folding, wrapping, sorting by size and type. The motions came back like muscle memory.

Soon, she was at a wounded soldier’s bedside, hands steady as she changed a dressing under Claire’s watchful eye.

The soldier—Private Evans, shrapnel in the thigh—winced.

“Sorry,” Leisel said softly, German lilt thickening her English. “I try be gentle.”

Evans blinked at her for a second, recognition flaring.

“You’re…German,” he said.

She tensed.

“Yes,” she whispered.

He looked down at his bandaged leg, then back at her.

“Well,” he muttered, “you do better than Thompson. He’s got hands like sandpaper.”

Thompson, on the other side of the tent, snorted. “Oi!”

A ripple of laughter ran through the cots.

Leisel’s shoulders dropped a fraction. A tiny smile pulled at the corner of her mouth before she wiped it away, almost guilty.

Work became her refuge.

She disinfected instruments, rolled bandages, took temperatures, fetched water. Under Claire’s guidance, she assisted with sutures, bracing herself when men screamed, holding their hands as the needle bit into flesh.

Each time she leaned over a British uniform, each time she pressed a pad of gauze to a wound caused by a German bullet or shell, the word on the sign around her neck—Verräterin—echoed in her head.

Traitor.

To whom?

To what?

One afternoon, a courier brought a canvas bag full of intercepted German mail. Most of it was routine—reports, requisitions, official nonsense. At the very bottom, someone had tossed a handful of civilian letters.

“Addressed to a hospital unit near Dresden,” the intelligence officer said. “Most of those places are rubble now. Might as well see if any of it’s useful.”

Hail’s hand brushed over one envelope, fingers catching on a familiar name.

An Schwester Leisel Brandt.

To Sister Leisel Brandt.

He hesitated.

Then he took it.

That night, under the glow of a single lantern in the corner of the tent, he approached her.

“This came through,” he said, offering the letter. “I think it’s yours.”

Her hands shook as she took it.

She opened it slowly, as if the paper might crumble. Her eyes moved quickly across the lines.

The hospital in Dresden no longer stands. The children’s ward is gone. We sleep in cellars when the sirens cry. God protect you, Leisel.

Her breath caught.

The letter slipped from her fingers onto the blanket.

She bowed her head, shoulders starting to shake—not with loud, cinematic sobs, but with the silent tremors of someone whose last threads had frayed.

Hail sat on the empty cot next to hers.

He didn’t touch her. Didn’t offer platitudes about ending war or rebuilding cities. He knew better.

It was the contrast that broke people more than the initial trauma.

Warm broth in her hands now, while somewhere in Germany children huddled in basements, sirens wailing.

Clean blankets here, while her colleagues dug splintered wards out of rubble.

Kindness in an enemy camp, while her own had left her on a post to die.

“If my people saw me here,” she whispered eventually, voice ragged, “they would say I betrayed them.”

He thought of the diary in his pocket that said, God forgive me.

“Surviving is not betrayal,” he said.

She didn’t believe him.

Not yet.

Weeks passed.

The front moved.

Lines on maps shifted eastward, arrows pushing deeper into Germany as winter dragged itself across Europe.

Orders came down.

Prisoners—combatants and non-combatants alike—were to be relocated to a more permanent camp farther from the front. The brass wanted consolidation, easier record-keeping, fewer strays.

Hail found Leisel in the medical tent, sorting vials of quinine with clinical focus that barely masked the tension in her jaw.

“We’re moving you,” he said.

Her hands stilled.

“Back?” she choked out. “To Germans?”

“No,” he said quickly. “To a British-run camp. Safer, more…organized.”

She exhaled, shoulders sagging with a mix of relief and fresh fear.

“When?” she asked.

“Tomorrow,” he said. “First light.”

She nodded, then went back to her vials.

That night, she wrote one more diary entry in the tent that had become both sanctuary and torment:

Tomorrow they send me away. I do not know where. I am afraid of leaving this place where the enemy gave me soap and sugar and blankets and a name that is not “traitor.” I am afraid of what waits anywhere else. I do not know which fear is worse.

In the morning, the trucks lined up at the edge of camp.

Hail watched as POWs climbed aboard—men with gray faces and hollow eyes, some defiant, some resigned. A few French villagers rescued from labor battalions moved with them, wrapped in blankets.

Leisel stood near the tailgate, coat buttoned, scarf tucked under her chin. Her wrists still bore faint scars under the gauze, but the cuts had closed.

Claire hugged her briefly, surprising them both.

“Don’t go getting yourself killed out of guilt,” she said gruffly. “You’re better at stitching than most of the orderlies. Would be a waste.”

Leisel managed a small smile.

“I…will try,” she said.

Hail stepped closer.

“This camp you’re going to,” he said, “has proper barracks. Better food. Red Cross oversight. It’s…not here. But it’s not a rope on a post either.”

She nodded.

“Thank you,” she said. The words were simple, but heavy.

“For cutting you down?” he asked.

“For…showing me,” she said, struggling to find the English. “That enemy is not…all monsters.”

He swallowed.

“And that Germans aren’t all monsters either,” he replied.

They looked at each other for a long moment—two people who, in another world, would never have crossed paths.

Then the driver called, “Time!”

Leisel climbed into the truck.

As it pulled away, she watched the camp recede—the tents, the smoky fires, the silhouettes of men she’d bandaged and those she’d never spoken to.

She pressed her hand to the diary tucked inside her coat.

She had entered that place with a sign around her neck declaring her a traitor.

She was leaving with a different label written in the quiet acts of those who’d treated her like something worth saving.

The road to the POW camp wound through countryside scarred by shell craters and burnt-out vehicles. Every village they passed bore the marks of war—shattered windows, walls pocked with holes, doors hanging crooked.

At a crossroads, the convoy slowed.

Ahead, a column of British and American soldiers had stopped, traffic jammed by something sprawled across the road.

Hail, riding in the lead jeep as escort, hopped out to see what it was.

It was a truck. German. Upended in a ditch, nose crushed, wheels spinning slowly.

Beside it, on the embankment, lay bodies.

Some wore gray-green uniforms. Others wore striped cloth.

Hail’s stomach dropped.

A work detail. Prisoners. Hit by their own retreating vehicle.

He barked orders to his men, setting up a perimeter, sending for medics. As he approached the nearest figure—a man in stripes, face caked with dried blood—the man’s eyes flickered open weakly.

“Bitte…” he rasped. “Wasser…”

Hail didn’t hesitate.

He shouted to the rear truck, “Nurse! We need hands!”

Leisel heard him through the canvas.

Without thinking, she jumped down.

Her boots landed in mud. The air smelled like petrol and iron.

The scene was chaos—moans, cries, men in all kinds of clothing twisted in unnatural angles. British soldiers moved among them, cutting fabric away, applying field dressings.

Leisel’s training took over.

She dropped to her knees beside the man in stripes, fingers feeling for a pulse even as her mind tried to process his sunken cheeks, the way his ribs showed through his skin.

“Wasser?” she repeated in German, already reaching for a canteen. “Langsam. Slowly.”

His eyes widened at hearing his language. He took a small sip, then another.

She moved from one body to the next, issuing quick commands in German and then in broken English, pointing medics to the worst cases.

“Here—compound fracture. Need splint.”

“This one—not breathing well. Maybe ribs.”

“Pressure here. He bleed too much.”

She didn’t notice the British lieutenant watching her from a few yards away.

He saw a German nurse, POW armband crooked on her sleeve, kneeling in the mud between German guards and half-starved prisoners in stripes. He heard the way she spoke to them, each one, with the same quiet urgency he’d heard in their own nurses’ voices.

He didn’t see a traitor.

He saw a nurse.

By the time the worst of the wounded were loaded into ambulances—British and American, headed toward field hospitals—the convoy had been delayed by hours.

Hail pulled Leisel aside.

“You didn’t have to do that,” he said softly. “You’re not on our roster.”

She looked at him, eyes tired but steadier somehow.

“I am nurse,” she said simply. “War…does not change that.”

He nodded.

“Remember that,” he said. “When someone back home tries to make you feel small using words they carved on a sign.”

She looked down at her wrist, at the faint rope marks.

“I am not…only what they call me,” she said.

“No,” he agreed. “You’re what you choose to be when nobody is watching.”

She climbed back into the POW truck, hands smeared with other people’s blood—German, British, nameless.

Somewhere, in some office, someone still had her marked as Verräterin.

But as the truck pulled away, she opened her diary one more time, scrawling with a blunt pencil:

Today I saw men in stripes, thinner than bones, treated by British medics as if they were their own. I saw enemy and prisoner bleed the same. I do not know what Germany is anymore. I do not know what I am. But I know this: When a man asked for water, I gave it. When a wound gaped, I closed it. When a life flickered, I tried.

Maybe that is my Fatherland now. Not a flag. Not a Führer. A choice.

The war ended months later.

For some, it ended in the rattle of machine guns falling silent, in surrender signed on tables crowded with uniforms. For others, it ended at train stations and docks, in lists of missing that would never turn into lists of found.

For Leisel, it ended in a processing hall where her name was checked against lists, her papers stamped, her status changed from “POW—Nurse” to “Repatriated Civilians.”

She stepped onto German soil again one gray morning.

The ruins of cities greeted her.

So did hunger.

So did shame.

News traveled slowly but inevitably.

Stories of camps. Of gas. Of pits and ash and numbers tattooed into flesh.

She read newspapers with trembling hands. She listened to shattered voices in church basements and soup lines. She saw the word Verräter—traitor—applied now to men and women who had once screamed it at others.

At night, under a borrowed blanket in a crowded shelter, she pulled out her diary and turned to the page where she had once written, Propaganda is a shadow that clings long after the voice is gone.

She added:

The shadow begins to lift.

In England, years later, a retired Captain Arthur Hail sat on a park bench, watching his daughter’s children chase pigeons. His left shoulder ached when it rained. The scar on his calf from a piece of French shrapnel twinged when the wind blew cold.

He had a box in his attic labeled “France” that he rarely opened.

Inside it, among the maps and faded letters and a photograph of a muddy camp, was a small leather diary.

Sometimes, on nights when the news showed new wars in places with names he didn’t know how to pronounce, he would lift the lid, thumb through the pages, and read a line or two.

Their kindness is a blade. It cuts me each time they treat me like I deserve to live.

He would close it, exhale, and think of a cold night in a French forest, a sign carved with the word Verräterin, and a voice saying “Bitte, please don’t shoot.”

He had no idea where Leisel Brandt was now.

He liked to imagine her in a small clinic somewhere, hands still steady over the wounds of whatever next conflict the world had conjured up, insisting, in German or English or whatever language the patient spoke, that survival was not betrayal.

He liked to imagine she had found a place where soap and sugar were not luxuries reserved for officers. Where blankets and broth were not weapons.

Where no one hung signs around necks to define a person by their worst fears.

Truth be told, he didn’t know.

The war had scattered them like leaves.

But he did know this:

For one suspended moment in a forest clearing, war had loosened its grip long enough for two enemies to see each other as something else.

Human.

And no amount of propaganda—his or hers—could erase that.

THE END

News

I never told my son that I’m a wealthy CEO who earns millions every month. He’s always assumed I live off a small pension. When he invited me to dinner with his fiancée’s parents, I decided to test them by pretending to be a poor woman who’d lost everything. But the moment I walked through the door, her mother tilted her chin and said, “She looks… so plain! I hope you’re not expecting us to help with the wedding costs.” I said nothing. But her father looked at me for one second—and suddenly stood up in fear…

I never told my son that I’m a wealthy CEO who earns millions every month. He’s always assumed I live…

My Parents Took Me To Court Over A Truck.A 2021 Ford F-150 Lariat That I Bought…

My parents sued me over a truck. Not totaled it. Not crashed it into a church or used it to…

After my husband hit me, I went to sleep without a single word. The next morning, he woke up to the smell of pancakes and a table full of food. He said, “Good, you finally get it.” But the moment he saw who was actually sitting at the table, his face changed instantly…

After my husband hit me, I went to sleep without a single word. The next morning, he woke up to…

At the divorce trial, my husband lounged back confidently and said, “You’re never getting a cent of my money again.” His mistress added, “Exactly, baby.” His mother sneered, “She’s not worth a dime.” The judge opened the letter I’d submitted before the hearing, skimmed it for a few seconds… and suddenly laughed out loud. He leaned forward and murmured, “Well… this just got interesting.” All three of their faces went pale instantly. They had no clue… that letter had already ended everything for them.

At the divorce trial, my husband lounged back confidently and said, “You’re never getting a cent of my money again.”…

CH2 – They Banned His “Hollow Log Sniper Hide” — Until It Dropped 14 Germans…

They Banned His “Hollow Log Sniper Hide” — Until It Dropped 14 Germans At 8:47 a.m. on September 18th, 1944,…

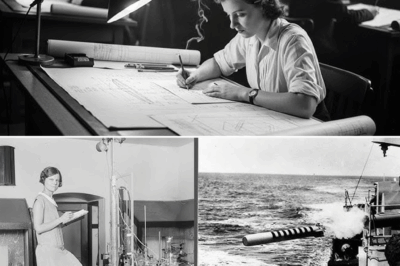

CH2 – The Female Engineer Who Saved 500 Ships With One Line of Code

By the winter of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic sounded like a broken heartbeat. Convoys vanished off the map…

End of content

No more pages to load