I was standing in our kitchen in Palo Alto, six months pregnant, holding the note I’d just written for my husband.

The pen was still warm from my fingers. The paper trembled as if it had its own pulse.

That was how Richard and I communicated—how we’d always communicated. Notes. Sign language. The quiet, deliberate choreography of hands and glances. Touches that lingered. Expressions that carried what voices usually did.

I held the note up over my shoulder the way I always did, angled so he could read it without making me turn around.

White or red? I’d written, even though I couldn’t drink.

I heard him step in behind me. Close. Close enough that I felt the shape of him like a shadow with heat. Close enough that his breath grazed the back of my neck.

Then he said, perfectly clearly, in a voice I had never heard before:

“Margaret, I need to tell you something.”

The paper slipped from my fingers.

It fluttered down between us like a dying bird, and I watched it fall as if the kitchen had turned into water and I was sinking through it.

Because my deaf husband had just spoken.

Let me go back.

Some stories don’t start where you wish they did. Some start where the crack first forms, invisible under the surface, the way thin ice looks safe until you place your weight on it.

I’m sixty-eight now. I’ve lived long enough to understand that the beginning is usually where the truth was trying to warn you.

It was 1991, and I was thirty-two years old.

Still single. Still working as a junior architect at a firm in San Francisco. Still living in a cramped studio apartment that swallowed most of my paycheck. The kind of place where the radiator hissed like it had opinions, and the neighbor’s music leaked through the walls like cigarette smoke.

Every Sunday my mother called.

Every Sunday she found a new way to tell me I was running out of time.

“Your sister Catherine just told me she’s expecting again,” she said one afternoon, like she was casually commenting on the weather. “That’ll be three grandchildren she’s given me.”

“Margaret,” she always said my name like a sigh. “Three.”

“That’s wonderful, Mom.”

“And the Johnsons’ daughter just got engaged. Remember Amy? You two used to play together. She’s twenty-six.”

I stared out my window at the fog rolling in over the bay, painting everything the color of old pearls.

“I’m happy for Amy.”

“I just don’t understand what you’re waiting for,” my mother continued, her voice tightening with that familiar blend of worry and accusation. “You’re not getting any younger. Men don’t want to marry women in their thirties who…”

“Mom,” I cut in, gripping the phone harder. “I have to go. I have work to finish.”

She always let me hang up, but she never truly stopped.

And if I’m being honest now, after decades of marriage and raising two children, I can admit that her calls landed where I was already sore.

I was lonely.

I was tired of coming home to an empty room where the silence didn’t feel peaceful—it felt like judgment.

Tired of watching my colleagues leave early for their kids’ soccer games while I stayed late to meet deadlines.

Tired of being the only single person at every family gathering, the one everyone tried not to look at too long, as if singleness were contagious.

So when my mother told me about Richard Hayes, I listened.

“He’s Dorothy Hayes’s son,” she said. “You remember Dorothy. She was in my book club.”

“I remember.”

“Her son started some kind of computer company. Very successful,” she added quickly, like that was the most important part. “Very handsome. And he’s ready to settle down.”

I groaned. “Mom, I’m not going on another one of your blind dates.”

“This is different.”

It wasn’t just her tone. It was the pause that came after, like she was choosing the least ugly way to present something.

“He’s… special, Margaret.”

I sat down on the edge of my bed.

“What do you mean, special?”

“He had an accident a few years ago. A motorcycle accident,” she said, softer now. “He lost his hearing.”

I blinked, surprised into stillness.

“He’s deaf?”

“Completely,” she said. “But he’s learned to adapt. He reads lips beautifully, and he knows sign language. Dorothy says he’s the same charming man he always was—just quieter.”

Then, like she couldn’t resist twisting the knife into the world, my mother added, “A lot of women don’t want to deal with that, you know.”

I heard what she wanted me to hear: You’re lucky to have a chance.

But what I felt—what I truly felt—was something more complicated.

A man who wouldn’t judge me for being thirty-two and unmarried.

A man who might be grateful for someone willing to step into his world.

A man who—because of his disability—might actually see me for who I was instead of what I wasn’t.

“Okay,” I said finally. “One dinner.”

Richard Hayes was everything my mother had promised and more.

Tall, with dark hair beginning to gray at the temples. Sharp brown eyes that watched my mouth when I spoke. Expensive suit, perfectly tailored. The kind of man who looked like he belonged in a magazine article about Silicon Valley’s rising stars.

Our first dinner was at an upscale Italian restaurant in San Jose. Candlelight, white linens, the kind of place where the waiters looked like they’d been trained to float.

I’d spent two weeks learning basic sign language from a book, practicing in my bathroom mirror until my hands cramped.

Richard made it easy.

He brought a small notepad and pen. When my clumsy signing failed, we wrote back and forth like teenagers passing notes in class.

Your mother talks about you constantly, he wrote. The brilliant architect daughter. The stubborn one who won’t settle down.

I laughed, embarrassed.

She makes me sound like a prize mare she’s trying to sell, I wrote back.

He smiled, and when he wrote his next message, I felt something shift inside my chest.

She undersold you.

It was simple. It was flattering. It was also—looking back—exactly the kind of line a man like Richard would know how to deliver.

We started dating, if you could call it that.

Dinners. Walks. Movies where we sat side by side in the dark and I forgot he couldn’t hear dialogue. He read subtitles when they appeared. Sometimes he squeezed my hand during romantic scenes, and I told myself that was how love sounded in his world.

I enrolled in a real sign language class after work.

Richard was patient with me, correcting my hand positions gently, guiding my fingers into the right shapes with warm hands and a careful smile. He showed me how to sign love, tomorrow, beautiful.

I thought I was learning his language.

I thought I was learning him.

His mother, Dorothy, was thrilled.

She invited us to Sunday dinners at her enormous house in Los Gatos. She watched us sign across the table with tears in her eyes like she was witnessing something holy.

“I was so worried he’d never find anyone,” she told me one evening when Richard stepped outside—supposedly to take a call. “After the accident, he withdrew so much. Stopped seeing friends. Broke up with his girlfriend.”

“Girlfriend?” I signed, then spoke, still learning how to blend the two worlds.

Dorothy’s expression tightened in a way that looked like pain but felt like judgment.

“Julia,” she said, with the kind of disdain women reserve for other women who threaten their stories. “She said she couldn’t handle being with someone who was deaf. Can you imagine the cruelty?”

I couldn’t.

I pictured Julia as shallow, selfish, small.

I thought: What kind of person abandons someone they love because of a disability?

I thought: I would never.

Eight months into our relationship, Richard proposed.

Not with spoken words—of course not—but with something that felt perfect in its quietness.

He took me to the beach at sunset. He wrote in the sand in enormous letters:

WILL YOU MARRY ME, MARGARET?

I cried so hard I couldn’t see. I signed yes over and over until my hands shook with it.

He slid a diamond ring onto my finger. It was beautiful. Expensive. The kind of ring that made my coworkers widen their eyes and my mother make a sound like she’d just won something.

I felt chosen.

We got married three months later in a small chapel in Napa Valley. Just immediate family and a few friends. The ceremony was conducted with a sign language interpreter.

When I signed my vows, tears streamed down my face.

I believed I had found my person: a man who valued patience and kindness over small talk and charm. A man who communicated intentionally. Every word written or signed with purpose.

Our wedding night, I expected something like magic.

Isn’t that what happens in stories? The curse breaks. The barrier disappears. The man speaks.

But Richard stayed silent.

He communicated with his hands—in sign language, and in other ways I won’t describe—and I fell asleep feeling cherished and complete.

We moved into a house in Palo Alto.

A real house. Backyard. Guest room. An office where I could spread out my blueprints instead of balancing them on a studio apartment table that also served as my desk and my dining room.

Richard’s company was doing well. Very well.

His business partners talked about going public within a year. IPO, they signed—or rather, they spoke around him, and he followed along.

Dorothy suggested I cut back my hours at the architecture firm.

Richard agreed enthusiastically in his silent way.

“You’ll want to be home more once the baby’s come,” Dorothy said over dinner, patting my hand like she was blessing me. “Now you can focus on what really matters. Being a wife and mother. That’s a woman’s true calling.”

I smiled politely because I didn’t yet know how to draw lines without guilt.

Four months after the wedding, I got pregnant.

We weren’t preventing it.

When the two pink lines appeared, I ran to Richard’s home office, crying and laughing and trying to sign through shaking hands. Finally I just shoved the test toward him like a confession.

His face lit up.

He pulled me into his lap, kissed me, held me so tight I could barely breathe.

Then he signed slowly and clearly:

YOU’LL BE AN AMAZING MOTHER.

The pregnancy was harder than I expected.

Morning sickness that lasted all day. Exhaustion that made it difficult to work. By five months, I quit the firm.

The commute, the long hours, the physical demands—it felt impossible with my body changing and my world narrowing to the shape of what Dorothy praised.

Richard was supportive.

We had money. We had comfort. We had the kind of life my mother used to describe like it was salvation.

But that day in the nursery—folding tiny onesies while the baby kicked inside me—I looked at Dorothy and asked, “Did you work after you had Richard?”

Her laugh was sharp, like a tiny slap.

“Oh, of course not. Richard’s father wouldn’t have allowed it.”

She always called him Richard’s father, never his name.

They’d divorced when Richard was in college, a scandal she rarely discussed. That day she mentioned him with a bitterness that made my skin prickle.

“Well, Richard and I discussed it,” I said firmly, though we hadn’t—not truly.

We’d written about it. We’d signed about it. But was that the same as a real conversation?

Could you have a real conversation in sign language with someone you’d only known for a year?

Six months pregnant, exhausted, hormonal, trying to be a good wife.

That’s when it happened.

That’s how I ended up in the kitchen with grilled chicken burning on the stove and a note in my hand.

White or red?

Richard walked in behind me.

I held the note up over my shoulder.

And he spoke.

“Margaret, I need to tell you something.”

The note fell.

Time stopped.

I turned slowly, my belly bumping the counter. Richard stood there looking at me with those sharp brown eyes, mouth moving, sound spilling out as if it had always belonged to him.

“I’m not deaf,” he said.

For a moment, I didn’t understand. The words didn’t have a place to land.

“I never was.”

My knees softened. I grabbed the counter.

The baby kicked hard, as if my body’s panic had become hers.

“What?” I whispered.

I wasn’t even sure sound came out.

Richard lifted his hands, palms out—a gesture that used to mean gentleness.

Now it looked like surrender.

“Let me explain.”

“Explain what?” My voice rose, strange and unfamiliar in my own throat. “What did you just say?”

He swallowed.

“I can hear you perfectly,” he said. “I’ve been able to hear everything this whole time.”

The kitchen tilted.

I pressed a hand to my belly, grounding myself in the only reality that still felt certain.

“You’ve been lying to me,” I said. “For almost two years.”

“It wasn’t lying exactly,” he said quickly, as if speed could make it less disgusting. “It was… more like a test.”

“A test.” The word tasted like poison. “A test?”

He hesitated, then nodded.

“My mother’s idea, actually,” he said. “After Julia left me, I was devastated. I thought we were going to get married and then she just left.”

He spoke faster now, words tumbling out like he’d been storing them up behind his teeth.

“She said I needed someone who would love me for who I really was, not for my money or my status. Someone patient. Someone kind. Someone who would stick around even when things were difficult.”

My hands clenched at my sides.

“So you pretended to be deaf.”

“Yes,” he said, and the ease of the confession made me nauseous. “Any woman who couldn’t handle that—who wouldn’t learn sign language, who got frustrated—she wasn’t right for me.”

My mouth went dry.

“And you found her,” I said, my voice flat. “Your special someone.”

Richard’s face softened, and I hated him for it.

“You,” he said.

The word should have been romantic.

It sounded like ownership.

“Does your mother know?” I demanded.

He blinked.

Just a moment. A pause so small it could have been nothing.

But it was everything.

“Oh my God,” I breathed, backing away. “Your mother knows.”

He didn’t deny it.

My chest tightened until breathing felt like dragging air through a straw.

“She’s known this whole time,” I said, louder now. “The tears at dinner. The gratitude that I accepted you despite your disability. That was all part of it.”

“Margaret—”

“You made me learn an entire language,” I said, voice rising, cracking. “You watched me struggle. You watched me quit my job. You let your mother pat my hand and tell me my calling was to be a wife and mother. You let me believe I was doing something noble.”

His face paled.

“You chose to learn sign language,” he said, as if that made it mine.

“I chose to learn sign language because I thought my husband was deaf,” I shot back. “I thought you needed me to meet you halfway. I thought I was being supportive. I thought I was being a good wife.”

My voice broke on wife, because the word suddenly felt like a costume I’d been tricked into wearing.

“You don’t have a disability,” I said, shaking. “You have a sociopath for a mother and apparently no moral compass of your own.”

“That’s not fair,” he said, wounded, as if fairness still lived in our kitchen.

“Fair?” I laughed, a harsh sound. “I learned an entire language. I quit my career. I’m carrying your child. And you’ve been lying to my face for two years.”

He flinched.

“I wasn’t lying to your face,” he muttered, and in another life that might’ve been a joke.

In my life it was a knife.

“Get out,” I said.

“Margaret, please—”

“Get out of my house.”

“It’s our house.”

“I don’t care,” I snapped. “Go stay with your mother. Since you two are apparently best friends and partners in fraud.”

He left.

He actually left.

He grabbed his keys and walked out the door, leaving me alone with smoke rising from the stove and my whole world collapsing in silence that no longer felt deliberate or loving.

It felt abandoned.

That night is blurred in my memory, as if my mind tried to protect me by smearing it.

I know I called my sister Catherine. I know I sobbed so hard she couldn’t understand me at first.

She drove over immediately.

She found me sitting on the kitchen floor, surrounded by sign language books, tearing pages out one by one like I could erase the last two years.

“He’s not deaf,” I kept saying. “He was never deaf. It was all fake.”

Catherine dropped beside me, arms wrapping around my shoulders.

“Oh, Maggie,” she whispered.

That was what she called me when we were kids.

No one else did.

Not Richard—who had only ever signed my full name, precise and formal.

Not Dorothy.

Not our mother.

Just Catherine.

“What am I going to do?” I whispered. “I’m six months pregnant. I quit my job. All my savings went into this house. I can’t just—”

I couldn’t finish, because I didn’t know what I couldn’t do.

Leave. Stay. Start over. Survive.

“Don’t call Mom tonight,” Catherine said gently.

But I did.

I dialed with shaking fingers, fury making me reckless.

My mother answered on the third ring, cheerful.

“Margaret! I wasn’t expecting to hear from you tonight. How’s my son-in-law?”

“Did you know?” I asked.

Silence.

“Did I know what, dear?”

“That Richard isn’t deaf,” I said, voice sharp. “That he’s been pretending the whole time. That he and Dorothy cooked up this scheme to test whether I was worthy.”

More silence.

Then—quietly, carefully—my mother said, “Dorothy mentioned they wanted to make sure any woman Richard married would be committed for the right reasons.”

The room went cold.

My mother knew.

Maybe not every detail, maybe not the cruelty of watching me quit my job and learn a language under false pretenses, but she knew enough.

She’d known I was being manipulated, and she’d let it happen because it fit her story: her spinster daughter finally married off.

I hung up.

I threw the phone across the room. It shattered against the wall like something finally breaking outside my body too.

“She knew,” I told Catherine, my voice small now. “My own mother knew.”

Catherine’s eyes filled with tears.

“That’s not—God, Maggie. That’s not okay.”

Richard called repeatedly.

I didn’t answer.

He showed up at the house. I locked the door and told him through the wood that if he didn’t leave, I would call the police.

He left letters—long handwritten letters explaining his reasoning, apologizing, begging me to understand.

I burned them without reading.

Dorothy came by too.

I didn’t let her in either.

“Margaret, please be reasonable,” she called through the door. “You’re carrying my grandchild. We need to discuss this like adults.”

“You lied to me for almost two years,” I shouted back. “You watched me struggle. You watched me give up my career. You cried at our wedding like you were grateful someone would accept your damaged son. All while knowing it was fake.”

“We were trying to protect Richard,” she insisted.

“No,” I snapped. “You were trying to control him. Control who he married. Make sure she was submissive enough, grateful enough, patient enough to take whatever you decided to dish out.”

She left, but she kept calling.

Richard kept calling.

My mother kept calling, though I stopped answering her too.

I was alone with my growing belly and my rage and my grief.

Because it was grief.

The man I’d married didn’t exist.

The relationship I’d built was with a fiction.

Every signed conversation, every note, every moment I’d treasured because it felt so intentional—tainted now.

Had he laughed at me when I practiced signing?

Did he find it amusing when I worked so hard?

Did he think I was stupid?

And worse—did I even know him at all?

What else had he lied about?

Catherine worried about me.

“You’re not eating enough,” she said. “You’re not sleeping. This stress isn’t good for the baby.”

“You want me to talk to him,” she added carefully, one evening as she watched me pick at food like a bird.

“I don’t even know if I want to be married to him anymore,” I said.

The words hovered between us.

Catherine looked stricken.

“Maggie, you don’t mean that.”

But I did.

Or I thought I did.

I didn’t know what I meant anymore.

Dr. Patricia Chen was the therapist Catherine found for me.

She was in her fifties, calm, with eyes that didn’t flinch when people brought her their ugliest truths.

In our first session she said, “Tell me what happened.”

So I did.

The whole story poured out: my loneliness, my mother’s pressure, the blind date, learning sign language, the wedding, quitting my job, the pregnancy, the reveal.

When I finished, Dr. Chen nodded slowly.

“That’s quite a betrayal,” she said.

I started crying again. It felt like I’d been crying for weeks.

“He says it was a test,” I choked out. “To find someone who would love him for himself.”

“And how do you feel about that?” Dr. Chen asked.

“I feel like I was a contestant on some sick game show,” I said. “And I didn’t even know I was competing.”

Dr. Chen’s voice stayed steady. “Your consent was violated. You entered a relationship under false pretenses.”

Finally—someone naming it.

But then she leaned forward slightly and said, “I need to ask you something, Margaret, and I want you to really think before you answer.”

I wiped my face.

“In those eight months before you married Richard—when you were dating him—did you love him?”

“Of course,” I said, offended by the question. “That’s why I married him.”

“Why did you love him?”

I opened my mouth, ready with a list.

Because he was kind. Thoughtful. Patient.

And because he was deaf.

I stopped.

“No,” I said quickly. “Of course not.”

“Are you sure?” Dr. Chen’s voice wasn’t accusing. It was gentle, which somehow made it harder.

“From what you described,” she continued, “the deaf man Richard pretended to be had very specific qualities. He was quiet. He communicated deliberately. He couldn’t interrupt you. He couldn’t talk over you. Every exchange required thought. He seemed patient because he had no choice but to be.”

My stomach tightened.

“I’m not saying you’re a bad person,” she added. “I’m saying attraction is complicated. Sometimes the things we think we love are what we’ve projected onto someone.”

I sat with that, miserable and angry.

“He still lied,” I said finally.

“Yes,” Dr. Chen agreed. “And that’s not okay. The question isn’t whether what he did was wrong. It was. The question is what you want to do now.”

What did I want to do?

I was seven months pregnant by then. Huge belly, swollen ankles, living off Catherine’s kindness and whatever savings I hadn’t already poured into a life that now felt contaminated.

Richard offered to keep paying the bills.

I refused.

Taking his money felt like accepting the lie.

“I don’t know if I can ever trust him again,” I admitted.

“That’s fair,” Dr. Chen said. “Trust once broken is very difficult to rebuild. But it isn’t impossible—if both people are willing to do the work.”

“What work?” I asked bitterly.

“Brutal honesty,” she said. “Transparency. Accountability. And time. A lot of time.”

I drove home—really to Catherine’s house—and felt the baby kick hard.

“What do you think?” I asked my belly, half-hysterical. “Should we give your father a chance?”

Another kick.

I laughed and cried at the same time.

Richard came to therapy the following week.

It was the first time I’d seen him in a month.

He looked terrible—thinner, gray under his eyes. His suit was wrinkled like he’d slept in it.

When he walked into Dr. Chen’s office, he automatically started to sign something, then caught himself.

“Sorry,” he murmured. “Habit.”

“Don’t,” I said sharply. “Don’t you dare use sign language with me again.”

His hands dropped.

Dr. Chen laid out ground rules.

I could ask any question, and Richard had to answer honestly—no matter what. He couldn’t leave until the session ended. And we both had to commit to coming back.

“Why?” I asked.

Richard looked down at his hands, then up at Dr. Chen, then finally at me.

“Because I’m a coward,” he said.

I hadn’t expected that.

Julia didn’t leave me because I wasn’t romantic enough, he admitted. She left because I’m… boring, Margaret. I’m good with computers and numbers, but I’m terrible with people. Small talk makes me anxious. Social situations exhaust me. I never know what to say.

“So you decided to say nothing at all,” I said.

He nodded.

“Being deaf gave me an excuse,” he said. “I didn’t have to make conversation at parties. I didn’t have to be charming. I could just exist, and people would think I was strong and brave instead of weird and antisocial.”

The shame in his voice sounded real.

It didn’t fix anything.

“And I was what?” I demanded. “Your perfect disabled-husband accessory? Someone to take care of you and make you look good?”

“No,” he said quickly. “You were… you were amazing. Smart and talented and beautiful. You felt out of my league. But as a deaf man, I had a chance. You saw me as someone who needed you—someone you could help—and I took advantage of that because I was selfish and scared.”

He looked at me, eyes wet.

“I didn’t think about how it would affect you,” he whispered. “I should have. I just… I wanted you to stay.”

I wanted to hit him.

I wanted to scream.

Instead I said, coldly, “You stole almost two years of my life.”

“I know.”

“You watched me give up my career.”

“I know.”

“And you can’t fix this with money,” Dr. Chen cut in gently, as if she could see Richard about to offer exactly that.

He swallowed.

“I know,” he said. “But I want to try. If you’ll let me.”

I didn’t answer.

We went to therapy every week.

Sometimes twice.

Richard answered every question, no matter how ugly.

Did he laugh at me? Sometimes, yes—when I messed up signs badly.

Did he read my private journals? No. And he looked genuinely wounded that I would think he would.

Did he love me?

“Yes,” he said, tears in his eyes.

I wanted to believe him.

I didn’t know how.

At eight months pregnant, I moved back into the Palo Alto house—our house.

But I had conditions.

Richard slept in the guest room.

We weren’t together.

We were two people cohabitating until I figured out what I could live with.

“That’s fine,” he said. “Whatever you need.”

Three weeks later, the baby came.

A girl.

Ten fingers. Ten toes.

A healthy set of lungs she demonstrated immediately.

When they placed her on my chest, I felt something crack open in me that wasn’t pain.

A kind of fierce love I’d never known existed.

I looked up and saw Richard in the corner of the delivery room, crying.

He looked like a man watching his own life transform in real time.

“Do you want to hold her?” I asked.

He nodded, unable to speak.

Actually unable to speak this time—choked up, stunned.

I handed our daughter to him.

His face changed.

Wonder. Pure, unfiltered wonder.

“She’s perfect,” he whispered.

“She’s ours,” I said.

We named her Clare.

Clare Margaret Hayes.

She changed everything.

Not immediately.

I was still furious. Still hurt. Still waking up some mornings feeling like I’d been tricked into someone else’s nightmare.

But Clare needed both of us.

And in those early exhausted weeks—midnight feedings, diapers, endless crying, hers and mine—Richard was there.

He was steady when I fell apart.

Patient with Clare’s screaming, calm with bottles and burp cloths. Competent in a way that made me realize he wasn’t pretending about everything.

One night at 2:00 a.m., Clare finally asleep after an hour of wailing, Richard and I sat in the nursery too tired to move.

“You’re good at this,” I said quietly.

“I had to be,” he replied. “I knew I’d already messed up with you. I couldn’t mess up with her too.”

We kept going to Dr. Chen.

Sometimes Clare slept in a baby carrier through our sessions.

Slowly, painfully, we started building something new.

Not the relationship we had before—that was dead, built on lies.

But something else.

Something honest.

“I’m still angry,” I told Richard six months after Clare was born.

“I know,” he said.

“I don’t know if that will ever go away completely.”

“I know.”

“And you don’t get to control this,” I said, voice trembling with the force of boundaries I was still learning to claim. “Not the timeline. Not the forgiveness. None of it. You did enough controlling already.”

“I understand,” he said.

And somehow he did.

He gave me space when I needed it.

He showed up when I needed that instead.

He went to therapy on his own, untangling whatever inside him made deception feel like an acceptable way to secure love.

Dorothy was a different story.

I didn’t speak to her for a year.

She called. Left messages. Sent cards.

I ignored them.

Finally, when Clare was fourteen months old, I agreed to meet Dorothy for coffee.

She looked older—more fragile—but her voice was still sharp.

“I owe you an apology,” she said.

“Yes,” I replied. “You do.”

She inhaled like it hurt.

“I thought I was helping Richard,” she admitted. “Protecting him. But I was really trying to control his life the way I couldn’t control my own marriage. And I hurt you terribly.”

“I’m sorry, Margaret.”

It wasn’t enough.

It could never be enough.

But it was something.

“If you want a relationship with your granddaughter,” I said carefully, “you need to understand I’m not the submissive, grateful daughter-in-law you thought you were getting. I have opinions. I have boundaries. And I won’t tolerate manipulation.”

Dorothy blinked, as if she hadn’t expected me to say it out loud.

“I understand,” she said.

“And you need therapy,” I added. “Real therapy. Whatever made you think that test was okay is not something I want around my daughter.”

She looked like I’d slapped her.

Then she nodded.

“I’ll find someone.”

She did.

It didn’t fix everything. Dorothy and I were never close.

But therapy made family gatherings bearable.

My mother was harder.

She still insisted she was “just trying to help,” that she didn’t know the extent of Richard’s deception. Maybe she didn’t. Maybe she did.

Either way, something broke between us.

We became cordial strangers.

Richard and I had another baby three years after Clare.

A boy.

We named him James.

And somehow—somehow—in the chaos of two kids and sleepless nights and laundry that never ended, Richard and I found our way toward something that looked like love.

Real love.

Not the fairy tale I’d imagined when I was thirty-two and lonely.

Something messier.

Harder.

More honest.

On our ten-year anniversary, we renewed our vows.

Small ceremony. Just us, the kids, a few close friends.

No interpreter.

No signing.

Just words.

Richard’s hands shook when he held mine.

“I promise to never lie to you again,” he said. “Even when the truth is uncomfortable. Even when it makes me look bad. Even when I’m scared.”

My throat tightened.

“I promise to keep choosing you,” I said. “Even when I’m angry. Even when I remember. Even when it would be easier to leave.”

That was twenty-eight years ago.

Now we’re sixty-eight and sixty-five.

Clare is married with two kids of her own.

James just got engaged.

Richard and I are still here—still working on it, still choosing each other.

It hasn’t been easy.

Some days I still feel the ghost of that betrayal, like a cold draft through a door that never quite sealed properly.

Some days I look at him across the breakfast table and remember the kitchen. The note. His voice. My world cracking like thin ice.

Some days I wonder what my life would have been like if I’d left. If I’d started over. If I’d never forgiven him.

But then I think about Clare’s wedding, watching Richard walk our daughter down the aisle with tears streaming down his face.

I think about James calling to ask his dad’s advice on engagement rings.

I think about quiet evenings on our porch, Richard’s hand in mine, talking about nothing and everything—feelings, fears, mistakes, the past, the future, the messy present.

We talk now.

We really talk.

In a way I never did with the silent man I thought I married.

And I realize something that still stings even after all these years:

Maybe Dr. Chen was right.

Maybe I fell in love with the idea of Richard, not the real person.

And maybe he fell in love with the idea of me too—the patient, understanding woman who would accept him as he pretended to be.

But we stayed long enough to meet each other for real.

We stayed long enough for the lies to burn away, leaving two flawed, complicated people standing in the ash, deciding whether to build again.

Was it worth it?

I don’t know.

Some days, yes.

Some days, no.

But it’s my life.

The one I chose.

The one I keep choosing.

And if there’s any truth I’ve earned at sixty-eight, it’s this:

Love that lasts isn’t love that never breaks.

It’s love that survives the breaking—and still finds a way to speak, finally, in its own honest voice.

THE END

News

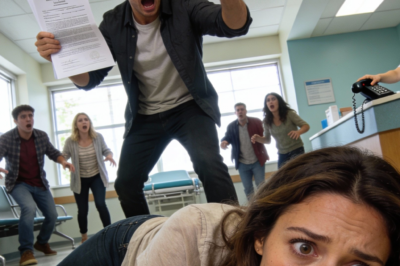

At The Hospital, My STEPBROTHER Yelled “YOU BETTER START…!” — Then Slapped Me So Hard I Did This…

Blood hit the linoleum in thick, slow drops—dark against that pale, speckled hospital-floor pattern they use everywhere in America, the…

CH2 – How a U.S. Sniper’s “Condom Trick” Took Down 48 Germans in 2 Hours

The first time William Edward Jones admitted the trick out loud, it wasn’t in Normandy. It wasn’t even in Europe….

CH2 – The Ghost Shell That Turned Tiger Armor Into Paper — German Commanders Were Left Stunned Silence

The hole was the size of a thumb. That was what got you, standing there in the Maryland winter with…

CH2 – Japanese Metallurgists Examined American Bullet Casings — Then Learned Why Their Own Weapons Jammed

The rain over Tokyo had a way of making the city feel like it was holding its breath. October 27th,…

CH2 – How One Woman Exposed a 6-Submarine Japanese Trap That Could Have Killed 10,000 Americans

At 2:17 a.m. on February 12th, 1944, Station HYPO didn’t feel like the nerve center of the Pacific War. It…

CH2 – The ‘Exploding Dolls Trick’ Fooled 8,000 Germans While Omaha Burned

The first time Captain Sam Keene heard the phrase “exploding dolls”, he thought somebody in Corps had finally cracked from…

End of content

No more pages to load