By the time Grace Mathers saw the thing in Ellie May’s ear, she’d already broken just about every rule a substitute teacher could break without being marched out of the building.

But none of that mattered when she knelt beside that tiny desk in the corner of her classroom and saw, really saw, what had been done to that child.

Her hands trembled as she leaned closer. The rest of the class hummed in the muffled chaos of crayons and whispers and the whirr of the old ceiling fan. It was health screening day at Roosevelt Elementary, and the school nurse had her cart set up at the front of the room, checking eyes and ears one by one.

Ellie sat where she always sat—tucked into the far corner by the window, as if someone had pushed her there and forgotten her. Small. Still. “Deaf,” they called her. “The deaf one.”

Grace had believed it for exactly three days.

Then a door had slammed, and a tiny shoulder had flinched, and everything had changed.

Now she was close enough to see the faint red marks behind Ellie’s ears, the way the skin was pressed and irritated, and the way something dark and wrong sat just inside the outer curve of the ear canal. Not wax. Not dirt. A packed, grayish plug that shouldn’t be there.

“Donna,” Grace whispered, throat tight. “Look.”

Nurse Donna Krebs glanced up from the boy she’d just finished examining, saw Grace’s face, and crossed the room with her otoscope in hand.

“Ellie, sweetheart,” Donna said gently, putting on a bright, practiced smile. “I’m just going to look in your ears. It won’t hurt at all.”

The little girl stared straight ahead, blank as always. But Grace could see the faint tension in her jaw.

Donna positioned the otoscope at Ellie’s left ear, angled it, and peered inside.

Her entire face changed.

The color drained. Her mouth fell open. She pulled back, checked the otoscope, then bent in again, this time more carefully.

“Oh my God,” she breathed.

Grace’s heart lurched. “What is it?”

Donna didn’t answer right away. She moved around to the right side, looking in Ellie’s other ear. Her hand shook.

“Grace,” she said, voice barely audible. “There’s something blocking both ear canals. Completely. It’s… this isn’t normal wax. It looks like—like packed debris. Years’ worth. I don’t even know how she’s been functioning.”

Grace looked closer.

Inside the outer edge of Ellie’s left ear, just visible without the scope, was that grayish plug she’d noticed. It was flush with the skin, as if something had been jammed in and never removed. The skin around it was red and raw.

“Can you get it out?” Grace whispered.

Donna hesitated only a second before reaching for a pair of sterile tweezers from her kit.

“Ellie, sweetie,” she said softly. “If anything hurts, you squeeze my arm, okay?”

Ellie’s eyes flicked to Donna’s face—just for a second, quick as a bird—and then back to the wall.

Donna braced herself, angled the tweezers, and grasped the visible edge of the plug.

Grace held her breath.

It didn’t come free easily. It resisted, then broke loose with a wet, awful sound that made Grace’s stomach twist. Donna pulled a wad the size of a grape out of the ear canal—a compacted mass of wax, dirt, and filthy cotton, mottled gray and yellow.

The smell hit them a second later. Rancid. Rotting.

Donna’s hand flew to her mouth. “Jesus.”

Ellie flinched, eyes widening. One small hand went to her ear.

Grace stared at the thing in Donna’s tweezers, horror turning into a cold, pure fury.

That was the moment everything snapped into perfect, terrible focus.

Whatever had been done to this child hadn’t been an accident.

Someone had let this happen. Someone had wanted this.

“Call 911,” Donna said hoarsely. “Now.”

Grace was already reaching for the classroom phone.

To understand how Grace got to that moment—to a Tuesday morning in a shabby Louisiana classroom, staring at the cruel truth packed into a five-year-old’s ear—you had to go back three weeks.

Back to the first humid September day she walked into Roosevelt Elementary and thought, This place feels familiar.

Chain-link fences. Cracked sidewalks. A building that smelled like bleach and old paper.

Poor neighborhood, the district office had said. Inclusion class. You’ll be covering for Mrs. Henderson while she’s on medical leave.

At thirty-eight, Grace had been teaching for fifteen years. She’d seen glossy suburban schools with PTA moms carrying monogrammed tumblers. She’d seen underfunded urban schools with leaky roofs and broken air conditioning. Roosevelt was the latter.

She didn’t mind. She’d grown up in places like this. Trailer parks and crappy apartments. Food stamps and hand-me-downs. An alcoholic mother who forgot to show up, and an “aunt” who eventually stepped in and saved her.

These were her kids.

Principal Harmon had met her at the office that first morning. Stern woman in her fifties, sensible shoes, straight skirt, mouth like a line drawn with a ruler.

“You’ll have Mrs. Henderson’s special ed inclusion group,” Harmon said as they walked the hallway. “Mixed abilities, some behavioral. Follow the lesson plans she left. We run tight protocol here, Ms. Mathers. No freelancing.”

“Of course,” Grace said, and meant it at the time.

Room 12 was small but sunny, alphabet posters curling at the edges, faded construction paper art on the walls. Tiny desks arranged in a horseshoe.

When the kids came in, Grace did what she always did—met every pair of eyes with a smile, learned names as fast as she could. Tyler with the dinosaur backpack. Mia with the purple glasses. Jamal who talked too loud because that’s how you talked in a loud house.

And then the little girl who walked straight to the corner, sat down at the desk by the window, and didn’t look at anyone.

She was tiny. Couldn’t have been more than five. Shoulder-length brown hair that needed washing. Clothes that hung off her narrow frame. Dark eyes that looked at everything and nothing at the same time.

“That’s Ellie May,” the teaching assistant, a tired-looking woman named Rhonda, whispered. “She’s deaf. Has been since she came here. We mostly just let her color while the others work.”

“Does she sign?” Grace asked.

Rhonda shrugged. “She doesn’t really do anything. School psychologist says severe hearing impairment, maybe cognitive delays. We’ve got documentation. Don’t worry. Just give her crayons.”

So that’s what Grace did, at first.

She slid a coloring sheet in front of Ellie. The little girl picked up a crayon without looking up and began to fill in a cartoon apple with slow, careful strokes.

Over the next few days, Grace watched her.

While the others did sight words and counting games, Ellie sat in her corner, silent, head down, coloring. At recess, while the rest of the kids ran screaming after a soccer ball or swung from the rusty monkey bars, Ellie stood by the fence, staring through the chain links at the street beyond, as if waiting for something that never came.

No one talked to her. No one sat with her at lunch. The teachers’ eyes slid past her like she was part of the furniture.

Deaf, Grace reminded herself. The school had medical records. There was a notation in her file, stamped and official: “Hearing impairment, nonverbal.”

And yet…

On Wednesday, during a music activity, Grace clapped her hands to get the kids’ attention. A loud, sharp crack.

Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Ellie flinch.

Just a small jerk of the shoulders, like someone had walked over her grave.

On Thursday, a classroom door down the hall slammed. Grace saw Ellie’s head turn toward the sound.

On Friday on the playground, Coach Brown blew his whistle three times, sharp and shrill. Ellie, standing by the fence, turned her head.

Grace’s stomach clenched.

She told herself it could be coincidence. Kids responded to movement, to vibrations, to the reactions of others.

But that night, in her tiny apartment a few miles from the school, she pulled Ellie’s thin file and spread it across her kitchen table.

The medical records were vague. One note from 2020: “Hearing impairment. Nonverbal.” No audiologist report. No follow-up. No recent evaluations.

No parent signatures, either. Just a shaky scrawl that was supposed to be her grandmother’s.

Ellie lived with a seventy-three-year-old grandmother and a forty-one-year-old uncle, according to the enrollment forms. No cell numbers. A landline that went straight to a disconnected message.

Three years in the system, and not one guardian had shown up for a parent-teacher conference. Teachers had ticked boxes and written “deaf, nonverbal” and moved on.

Grace stared at the papers until the words blurred.

Her instincts—honed over years of working with vulnerable kids—were screaming at her.

Something wasn’t just off.

Something was wrong.

On Monday, she decided to test it.

During quiet reading time, when the class was scattered at their desks with picture books and early readers, Grace walked slowly to Ellie’s corner.

Her heart hammered. She felt ridiculous, like she was about to stick her hand in a hornet’s nest just to see if they stung.

She knelt beside Ellie’s desk, close enough to smell the sourness of unwashed hair and skin.

The little girl’s eyes stayed on her coloring page.

Grace leaned in until her lips were inches from Ellie’s ear, and in a voice barely louder than a breath, she said, “Ellie, can you hear me?”

For a fraction of a second, Ellie’s entire body went rigid. Her eyes widened just a hair. Then, as if she’d caught herself, her face smoothed back into that empty, practiced blankness.

It was subtle. If Grace hadn’t been watching for it, she might have missed it.

But she saw it.

She sat back slowly, her own breath coming short.

“You heard me,” she whispered, to herself as much as to the child.

Ellie’s gaze flicked to her face, just once, and then dropped again.

Grace didn’t sleep that night.

Every time she closed her eyes, she saw that little flinch. That flicker of awareness. The way Ellie had slammed a curtain down over it, the way kids did when they learned that being seen was dangerous.

By morning, Grace had made up her mind.

She wasn’t going to let this go.

Principal Harmon was not pleased.

“Ms. Mathers,” she said, sitting behind her crowded desk, fingers steepled. “You’ve been here… what? One week?”

“Eight days,” Grace said. Her palms were damp. She wiped them on her skirt under the desk.

“And in that time you’ve decided that our medical classification of a student is wrong?” Harmon’s voice was flat, her eyes hard. “That you, as a substitute, know better than licensed professionals?”

Grace wanted to flinch. She didn’t.

“I’m saying,” she said carefully, “that I’ve observed Ellie reacting to sounds. The door slamming, the whistle on the yard. Yesterday, I whispered in her ear and she responded. I don’t think she’s deaf, at least not completely. I think something else is going on.”

Across from her, the district social worker, Linda Voss, adjusted her glasses. She was in her forties, tired eyes behind her lenses, a chain dangling from the frames like jewelry.

“You whispered in a hearing-impaired child’s ear to see if she ‘responded’?” Linda said, voice sharp. “Do you understand how that sounds, Ms. Mathers?”

Grace felt her face heat. “I wasn’t trying to… antagonize her. I’m trying to help her. Her file—”

“Her file has official documentation,” Harmon cut in. “She was classified three years ago. That classification has been reviewed at the district level. You are not qualified to overturn it based on a week of anecdotal observations.”

“She reacts to sounds,” Grace insisted. “She’s completely isolated. No one has re-evaluated her in years. Don’t you think—”

“What I think,” Linda said crisply, “is that you are dangerously close to harassing a vulnerable family. We have protocols. If the Thornhills felt Ellie needed further assessment, they’d request it.”

“Have they ever answered the phone?” Grace shot back. “Have they ever come to a conference? I’ve tried calling. The number is disconnected.”

Linda’s mouth thinned. “You’re a temporary substitute teacher, Ms. Mathers. You were hired to maintain continuity in the classroom. Not to play detective. Ellie’s case is closed.”

“Closed?” Grace repeated. “She’s five.”

“That’s enough,” Harmon said. “Do I make myself clear?”

Grace walked out of the office feeling like someone had shoved cotton into her ears.

But the message came through loud and clear.

Back off, or we’ll make you regret it.

She didn’t back off.

Her next ally was the school nurse.

Donna had been at Roosevelt for years. Gray hair in a practical bun. Comfortable shoes. A cabinet full of inhalers and ADHD meds and bandages for scraped knees.

“Do you believe she’s deaf?” Grace asked one afternoon in the clinic, watching Donna line up little paper cups of lunchtime pills.

Donna glanced at the closed door, then back at Grace.

“I’ve… wondered,” she admitted. “Sometimes when I drop something metal, she jerks. Sometimes when I call another kid’s name, I swear I see her head move.”

“So why hasn’t anyone done anything?” Grace demanded.

Donna’s shoulders sagged.

“Because wondering isn’t enough,” she said softly. “Because to challenge an official diagnosis you need a paper trail a mile long and administrators who don’t see you as a troublemaker. Because the last time I raised my voice about a child here, I almost lost this job.”

“Help me,” Grace said. “Please. Just… watch her. If I’m wrong, I’ll drop it. But if I’m right—”

Donna looked at her for a long moment, eyes searching Grace’s face.

“You could lose your position over this,” she said. “Harmon doesn’t like waves.”

“I know,” Grace said. “But I keep seeing myself in that corner. Waiting for someone to notice.”

Something in Donna’s expression softened.

“I’ll observe quietly,” she said. “But, Grace? Be careful.”

The next strange thing Grace noticed was the red marks.

During art time, she knelt beside Ellie’s desk, watching her carefully grip a crayon in her small hand. Ellie’s hair was tucked behind her ears, and for the first time Grace saw the faint, raw lines just behind each one.

Not bruises. Not fingerprints.

Pressure marks.

As if something tight had been there for a long time. Headphones? Band? Devices?

Ellie’s file mentioned no hearing aids. No cochlear implants.

Grace’s blood went cold.

“Ellie,” she said softly, not expecting a response. “You’re safe here. You hear me?”

Ellie didn’t look up. Her crayon moved carefully within the lines.

But her fingers trembled, just a little.

That night, Grace pulled every sheet of paper out of Ellie’s file again.

Buried in the paperwork was a scribbled note from two years earlier, initialed by some social worker Grace didn’t know: “Concern re: possible benefit fraud. Family receiving disability payments. Recommend follow-up investigation.”

Below it, in a different hand: “Case closed. Family provided documentation. No evidence of fraud.”

No details. No follow-up. No visits.

Grace closed her eyes.

She knew enough about government benefits to know that families caring for disabled children could get help. There were forms, and hoops, and evaluations. But there were also checks.

And people who knew how to game the system.

The next day, Grace cornered Harold, the custodian, in the hallway.

“You okay, Ms. M?” he asked, seeing her face.

“Harold,” she said, lowering her voice, “what do you know about the Thornhills?”

He blinked. He’d been at Roosevelt for forty years. He knew more than most principals.

“You mean that little girl,” he said. “Ellie May.”

“You’ve noticed,” Grace said.

“I’ve been changing her trash and mopping around her desk for three years,” he said quietly. “Hard not to notice when a kid never talks, never laughs, never has anybody show up for them.”

“You live near them, right?” she asked. “On Cypress?”

“Two blocks down,” he said. “House is falling apart. Grandma—Darlene—barely comes out. When she does, she looks… lost. Like she doesn’t know where she is.”

“And the uncle?” Grace asked.

Harold’s mouth tightened.

“Boyd,” he said. “Keeps odd hours. Neighbors don’t like him much. Drinks. Shouts a lot. Folks hear things sometimes. But in that neighborhood?” He shrugged. “People got their own troubles. They mind their business.”

“Have you ever seen Ellie outside?” Grace asked.

“Once or twice,” he said. “Always in clothes too big, shoes flapping. Holding onto Grandma’s sleeve like a little ghost.”

That afternoon, Grace talked to Mrs. Chen, the art teacher.

“I remember when Ellie first came,” Mrs. Chen said, eyes sad. “She was two. Her mother brought her—young, overwhelmed. Then one day the mom just… stopped coming. The grandmother started dropping Ellie off instead. And then, right around the time the mom disappeared, suddenly Ellie was deaf. Just like that. No fuss. No questions.”

“No one wondered?” Grace asked.

“Oh, we wondered,” Mrs. Chen said. “But wondering isn’t enough.”

Grace was so tired of hearing that line she could scream.

Two days later, she did something the rule book would have called absolutely unacceptable.

She drove to 1847 Cypress Street.

It was worse than she’d imagined.

Sagging porch. Roof patched with mismatched shingles. Yard choked with weeds and litter. A screen door half off its hinges.

She parked across the street, heart pounding, and walked up the cracked concrete.

When she knocked, nothing happened at first. She was about to knock again when she heard movement inside—the slow, shuffling drag-step of an old person.

The door opened a few inches, held on a chain.

An elderly woman peered out. Wisps of white hair, watery blue eyes, skin like tissue.

“Y-yes?” she said, voice uncertain, as if she’d forgotten what doors were for.

“Mrs. Thornhill?” Grace asked. “I’m… I’m Grace Mathers. I’m Ellie’s teacher at Roosevelt.”

The old woman blinked slowly.

“Ellie,” she repeated, like testing the name on her tongue. “She’s… she’s a good girl. Very quiet.”

“I’d love to talk to you about how she’s doing,” Grace said gently. “See how we can help her at school.”

The woman’s eyes darted behind her, into the house. Her shoulders hunched.

“Boyd handles that,” she said quickly. “Boyd says Ellie’s fine. We got papers. Doctor papers. Says she’s deaf. Always been deaf.”

“Mrs. Thornhill,” Grace began, “I don’t think—”

“Who’s at the damn door?” a man’s voice barked from inside. Harsh. Angry.

The woman flinched.

“It’s—it’s just a teacher,” she said over her shoulder. “She was just leaving—”

Footsteps. Heavy, fast. The chain rattled. The door slammed shut inches from Grace’s face.

She stood there on the porch, stunned.

Through the thin wood, she heard muffled shouting.

“I told you no more people coming around here asking questions! You wanna lose everything?”

“I’m sorry, Boyd, I—”

Grace backed away, her pulse hammering. Every instinct told her to run. To get the hell away from that house.

She did.

Back in her car, hands shaking, she sat and stared at the sagging blue house.

The curtain in the front window shifted.

For just a second, Grace saw a small face pressed to the glass. Dark eyes. Brown hair.

Ellie.

Then the curtain dropped back into place.

Grace drove home with her jaw clenched so tight it hurt.

That night, she called the number on the Louisiana Child Protective Services website.

And hung up before it connected.

Because she knew how these things went. Form letters. Overworked caseworkers. Files marked “unfounded” and shoved in cabinets.

She didn’t want to be another voice shouting into a void.

She wanted proof.

Proof came on hearing screening day.

It came in the form of a filthy gray plug pulled from a child’s ear and the smell of rot in a classroom full of five-year-olds.

“Call 911,” Donna said again, more sharply, the mass of debris trembling in her tweezers.

Grace didn’t hesitate.

She grabbed the wall phone, punched in the numbers.

“911, what’s your emergency?”

“This is Roosevelt Elementary School,” Grace said, fighting to keep her voice level. “We have a five-year-old with a severe ear blockage. Our nurse just removed… something. There’s significant neglect. We need an ambulance.”

As she spoke, she watched Ellie.

The little girl’s hand was still on her ear, eyes wide. She looked… stunned. Like the world had gotten suddenly louder.

“Ma’am, is the child conscious?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yes,” Grace said. “But there’s visible infection, and we suspect long-term medical neglect.”

“We’re sending paramedics,” the dispatcher said. “Stay on the line.”

The classroom door swung open before Grace could respond.

Principal Harmon stood there, face crimson, Linda Voss at her shoulder.

“Ms. Mathers,” Harmon snapped, taking in the scene. “Nurse Krebs. What do you think you’re doing?”

Donna held up the tweezers, the wad of filth still clamped in the tips.

“What we are doing,” she said, her voice shaking with fury, “is treating an emergency that has been ignored for years.”

Harmon’s mouth opened, then closed.

“This is a routine screening,” Linda said quickly. “You had no authority to perform any invasive procedure—”

“Invasive?” Donna repeated. “I removed a foreign body blocking this child’s ear canal. Both ears are impacted. This is not optional. This is abuse.”

The phone still dangled in Grace’s hand.

“The paramedics are on their way,” the dispatcher reminded her. “They’ll be there in under ten minutes.”

“We have an ambulance coming,” Grace said, almost daring Harmon to argue with 911.

Harmon’s nostrils flared.

“You will document this as an incomplete screening,” she said to Donna. “And you,” she pointed at Grace, “will step away from that child immediately.”

“No,” Grace said.

The word surprised even her.

“Excuse me?” Harmon said.

“I said no,” Grace repeated, more firmly. “We called 911. This is now an emergency medical situation. You don’t get to make this go away.”

“Ms. Voss,” Harmon said sharply, “call central office. Inform them—”

“I already have,” Linda said, eyes cold. “And I’ll be documenting both of your unauthorized actions in my report.”

Sirens wailed in the distance.

Ellie flinched again, her eyes flying to the door. For the first time, she looked like a child, not a hollow shell.

Grace crouched beside her.

“It’s okay,” she murmured. “Those sirens are helpers coming. They’re going to make your ears better. You’re safe.”

Ellie’s hand found Grace’s fingers and curled around them.

Everything moved fast after that.

Paramedics flooded the classroom, bringing a rush of cold autumn air and the smell of antiseptic.

They examined Ellie quickly and efficiently.

“How long has this been like this?” one of them muttered, peering into her ear with a portable otoscope.

“We don’t know,” Donna said. “Years, maybe. Both canals are completely obstructed. There’s infection, swelling. She needs a hospital.”

“We’ll take her to Children’s,” the paramedic said, glancing at his partner. “Page ENT on the way.”

Linda stepped forward. “I’ll ride with her, as district social worker,” she said. “I—”

“No, you won’t,” Donna snapped. “You had your chance to do your job two years ago. You closed her case without even seeing her.”

Linda went pale.

The paramedic looked between them. “We can take one adult,” he said. “Preferably someone the child trusts.”

Ellie’s fingers tightened around Grace’s.

“Please,” she whispered, voice so faint Grace almost didn’t catch it.

It was the first word Grace had ever heard from her.

“Her teacher,” Donna said decisively. “She goes.”

Harmon sputtered. “Absolutely not. Ms. Mathers is—”

“Suspended?” Grace finished bitterly. “Fired? You can do whatever you want to me later. Right now I’m getting in that ambulance.”

The paramedics weren’t interested in school politics.

“We’re going,” one of them said. “Now.”

They lifted Ellie carefully onto the gurney. She kept her eyes on Grace the whole time.

“Stay,” she whispered again, stronger now.

Grace climbed into the back of the ambulance, Donna’s hand briefly squeezing her arm before the doors shut.

As the siren wailed and the ambulance pulled away from the curb, Grace felt fear, rage, and something else thread together in her chest.

Resolve.

Whatever this was—whatever she’d stepped into—there was no going back now.

The emergency department at Children’s Hospital was a blur of bright lights and rapid questions.

Names. Ages. Allergies. Medical history.

“How long has she been deaf?” a resident asked, checking Ellie’s pupils.

“She’s not,” Grace said. “Not really. That’s the problem.”

ENT specialists arrived. Grace sat in a plastic chair just outside the exam room, watching through the narrow window as doctors examined Ellie’s ears more thoroughly than anyone had in years.

Donna arrived twenty minutes later, out of breath. Behind her came a woman with a badge around her neck: LOUISIANA DCFS.

“Ms. Mathers?” she said, extending a hand. “I’m Agent Patricia Drummond. I spoke to the paramedics. Nurse Krebs gave me the quick version on the phone. We need the full story.”

Grace told her.

About the flinches. The turning head. The whispered name. The red marks behind Ellie’s ears. The visit to Cypress Street. The slammed door. The disconnected phone. The mysterious disability benefits in the file. The hearing screening. The plug.

Patricia listened without interrupting, her eyes sharp, her pen moving fast across her notebook.

“Nurse Krebs?” she asked when Grace finished.

Donna handed over her written notes. “There’s your proof,” she said. “Visible obstruction. Evidence of years of neglect. That’s just my professional assessment.”

Patricia read, frowned, and looked toward the exam room.

“I’m going to need everything you have,” she said. “Files. Copies of those medical forms. Any previous notes. We’ll subpoena if we have to.”

“What happens now?” Grace asked. “To Ellie?”

“That depends on what the doctors find,” Patricia said. “But given what I’m hearing already? This child is not going back to that house.”

An ENT surgeon finally emerged after what felt like hours.

She pulled off her gloves, tired lines etched into her face.

“I’m Dr. Patel,” she said. “We’re prepping her for a procedure now. The blockage is severe. Both canals are impacted with what appears to be years of wax, debris, and foreign material. There’s infection, but the inner structures look intact on imaging.”

“Can she hear?” Grace asked.

Dr. Patel’s gaze softened.

“We won’t know the full extent until we clear everything out,” she said. “But my preliminary assessment? There’s a very good chance she’ll regain full or near-full hearing once the swelling resolves. Physically, she was never deaf. Circumstances deafened her.”

“Circumstances,” Grace repeated, the word burning on her tongue.

Neglect. Fraud. Indifference.

Patricia’s jaw tightened.

“We’ll need your full report as soon as possible, Doctor,” she said. “We’re opening a formal abuse and neglect investigation.”

“And I’m calling in a favor from a pediatric psychologist,” Dr. Patel added. “Because whatever happened to her ears is just the part we can see.”

Ellie’s surgery took two hours.

Grace sat in the waiting room with Donna and Patricia, a Styrofoam cup cooling untouched between her palms.

“I’m sorry,” she said suddenly.

Donna frowned. “For what?”

“For dragging you into this,” Grace said. “For making you risk your license, your job.”

Donna snorted softly.

“Grace,” she said, “I’ve been in this clinic for over twenty years. I’ve seen kids come in hungry, bruised, exhausted. I’ve watched administrators tell me to mark it down and keep quiet. I did my time biting my tongue. If I lose this job over helping Ellie, so be it.”

Patricia nodded.

“And I’ve been in DCFS for a decade,” she said. “I’ve closed files like Ellie’s because the family waved a piece of paper, and I had fifteen other emergencies on my desk. I’m not proud of that. I’m not proud that she slipped through the cracks. But that ends now.”

Grace looked at both women.

It wasn’t just her anymore.

That helped.

When Dr. Patel finally came back, Grace’s breath caught.

“How—” she began.

“The procedure went well,” Dr. Patel said. “We removed a significant amount of impacted material. I’m not exaggerating when I say it looks like years of neglect. But the eardrums are intact. The inner ear structures look healthy.”

“And…?” Grace pressed.

“And once the swelling goes down,” Dr. Patel said, “she should be able to hear.”

Grace’s knees nearly gave out.

“She’ll need speech therapy,” Dr. Patel continued. “She’s missed years of language input. Sound is overwhelming for her right now. Everything is loud. But children are resilient. With support, with the right environment…” She smiled faintly. “She has a real shot.”

“Thank God,” Donna whispered.

“Can I see her?” Grace asked.

“In a bit,” Dr. Patel said. “We’re monitoring her as she comes out of anesthesia. But I think,” she added, glancing at Patricia, “it would be good for her to wake up to a familiar voice. A safe voice.”

Room 412 was painted a soft blue, clouds stenciled on the wall above the bed.

Ellie lay there, small and pale against the white sheets, bandages wrapped around both ears. An IV dangled from her arm.

Her eyes fluttered.

“Hey, sweetheart,” Grace said softly, stepping closer.

Ellie’s eyes opened.

They focused on Grace’s face.

“Hey,” Grace repeated, barely daring to breathe. “Can you hear me?”

Ellie blinked.

Her mouth moved.

“Stay,” she whispered, voice rough and scratchy.

Grace swallowed past the lump in her throat.

“I’m right here,” she said. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Ellie’s gaze traveled around the room, taking in the beeping monitor, the soft shush of the air vent, the distant echo of footsteps in the hallway.

“It’s loud,” she mumbled.

“I know,” Grace said. “We’ll take it one sound at a time. Okay?”

Ellie’s small hand reached out and grabbed two of Grace’s fingers.

She held on.

The investigation moved fast after that.

Patricia’s team dug into the Thornhills’ records with a fierceness that almost made Grace vindicated.

Ellie’s pediatric records from age two showed normal hearing. Then, six months later, a sudden notation of “severe hearing impairment.” No audiology report. A doctor’s signature that didn’t match any licensed practitioners in the county.

“Forgeries,” Patricia said, sliding the printouts across the coffee shop table a week later. “Boyd’s handiwork. Sloppy, but apparently good enough for overworked clerks.”

Financial records told the rest of the story.

Ellie’s supposed “disability” had qualified the Thornhills for significant federal assistance. Monthly payments. Extra food support. Medical allowances.

Not one receipt showed purchases for hearing aids. Therapy. Specialized equipment.

The money went to liquor stores, payday loan companies, car parts.

“Ellie was a paycheck,” Patricia said grimly. “A way to keep the lights on and Boyd in beer.”

“What about her mother?” Grace asked, voice tight.

Patricia sighed.

“Nineteen when she had Ellie,” she said. “Drug problems. She left the kid with her mother ‘for a few days’ and never came back. We’re still trying to track her. Father’s unknown.”

“And Linda?” Grace asked carefully.

Patricia’s expression chilled.

“Two years ago, a neighbor called in a concern,” she said. “Said they heard shouting, saw Ellie looking neglected. That case landed on Voss’s desk. She made one phone call. Accepted Boyd’s ‘we got doctor papers’ story. Closed the file without ever setting eyes on Ellie.”

Grace squeezed her coffee cup so hard it crumpled.

“She could have stopped this,” she whispered. “Two years ago.”

“She had forty other cases and no backup,” Patricia said. “It’s not an excuse. It’s an explanation. She’s under review. But the system failed Ellie long before Linda Voss put pen to paper.”

The school hadn’t exactly covered itself in glory, either.

Harmon tried to frame Grace and Donna’s actions as “unauthorized” and “unprofessional.” But when DCFS and the hospital reports came in, the district started backing away from Harmon faster than a snail from salt.

Donna got a formal reprimand in her file and quiet apologies in hallways.

Grace got suspended.

When she pushed harder, she got something else.

A choice.

“If you pursue a formal complaint against the school,” Patricia told her, “they’ll make your life hell. They’ll blacklist you from the district. You have to decide what fight matters most.”

Grace didn’t even hesitate.

“The one with Ellie in it,” she said.

Ellie went to Magnolia House when she was discharged.

Temporary foster care.

Big yellow Victorian. Kids’ drawings on the walls. Staff that tried their best with too many small bodies and not enough hands.

Grace went to see her as soon as she was allowed.

She walked into the common room and spotted Ellie immediately—curled up on a beanbag in the corner, book open in her lap.

“Hey, sweetheart,” Grace said.

Ellie looked up.

Then she did something no one had seen her do in years.

She ran.

Across the room, full tilt, small shoe soles thumping on the floor.

She barreled into Grace and wrapped her arms around her waist.

“You came back,” she said, voice wobbly but clear.

“I told you I would,” Grace said, dropping to her knees and hugging her tight. “I always will.”

The foster coordinator, Mrs. Fletcher, smiled from the doorway.

“She’s been waiting for you,” she said. “Hearing’s still overwhelming, but she’s adjusting. She jumps at doorbells. Shuts down when more than one person talks at once. But she’s trying.”

Ellie pulled back and looked up at Grace.

“Miss Grace?” she said.

“Yes, baby?”

“You my teacher?”

Grace swallowed.

“I was,” she said. “But now I’m… something else.”

“What?” Ellie asked.

Grace took a breath.

“How would you feel,” she said slowly, “if I tried to be your family?”

“Like Grandma?” Ellie asked, eyes wide.

“Like… like a mama,” Grace said, the word catching in her throat.

Ellie stared at her.

Then, very quietly, she whispered, “Forever?”

Grace’s eyes filled.

“If they’ll let me,” she said. “That’s what I want.”

Ellie’s answer was immediate.

“Please,” she said. “Please don’t leave me here forever.”

Grace hugged her, felt the small, fierce strength in that tiny body.

“I’m going to try,” she said. “With everything I’ve got.”

The foster parent process was grueling.

Background checks. Home inspections. Training sessions about trauma, attachment, court procedures.

Grace jumped through every hoop.

She scrubbed her one-bedroom apartment until it shone. Harold built a small bookshelf and a twin bed. Donna bought a comforter with little stars on it.

“You think they’ll approve a single substitute teacher?” Grace asked Patricia one afternoon, voice betraying her fear.

“I think,” Patricia said, “they’ll approve someone who has already shown they’ll go to war for this kid.”

Grace did resign from Roosevelt.

She drafted the letter, printed it, signed it, and handed it in without fanfare.

Harmon accepted it with a tight smile and no eye contact.

Grace walked out of that office lighter.

She picked up freelance tutoring gigs. Helped kids from the neighborhood with reading and math. Scraped by on less money than she’d ever made. Cut corners. Skipped dinners out.

Every sacrifice felt worth it.

On a damp October morning, Patricia called.

“You’re approved,” she said. “Home study cleared. Training completed. Now we have to go in front of a judge.”

“Ellie?” Grace asked.

“She wants you,” Patricia said. “She tells everyone you’re ‘her Grace.’ Now we just have to make it official.”

The custody hearing was in a cramped parish courtroom with buzzing fluorescent lights and scuffed wooden benches.

Boyd was there, shackled at the wrists, orange jumpsuit hanging off his frame. If he’d ever been intimidating, prison had stripped that away, leaving something smaller and sadder.

He didn’t look at Grace.

He didn’t look at Ellie.

He stared at the table.

The prosecutor laid out the case: forged medical records, diverted disability payments, neglect documented by hospital records and photographs.

Boyd’s public defender muttered something about stress, about poverty, about “not understanding the consequences.”

The judge listened, impassive.

Then she turned to Grace.

“Ms. Mathers,” she said. “Why do you want to adopt this child? You’re single. You gave up your teaching job. This is no small undertaking.”

Grace stood.

“I know,” she said. “I know I don’t look like the picture in the brochures. I don’t own a house. I don’t have a husband. I don’t have a white picket fence.”

She glanced at Ellie, who sat beside Patricia, small hands folded, eyes fixed on her.

“But I have this,” Grace said. “I have the ability to see her. I saw her when everyone else looked past her. I noticed when she flinched, when she turned her head, when she sat in a corner and disappeared. And I did something about it. I’ll keep doing something about it for as long as I live.”

She took a breath.

“I grew up like her,” she said, voice softer now. “Invisible. Hungry. Waiting for someone to notice. A woman did. She pulled me out. Now it’s my turn to do that for Ellie. I’m not perfect. But I’m here. And I’m not going anywhere.”

The judge studied her for a long moment.

Then she looked at Ellie.

“Ellie,” she said gently. “Do you understand what it would mean for Grace to be your mother?”

Ellie nodded. “It means I don’t have to go back,” she said. “It means I get to stay with her, and she loves me.”

“And how do you feel about that?” the judge asked.

Ellie’s answer was simple.

“Safe,” she said.

The judge’s face softened.

“Mr. Thornhill,” she said, turning back to Boyd. “You have anything you wish to say?”

Boyd shook his head once, dully.

The judge lifted her gavel.

“Then by the power vested in me by the state of Louisiana,” she said, “I terminate the parental rights of Ellie May’s biological guardians and grant full legal custody and adoption to Ms. Grace Elaine Mathers.”

The gavel came down with a crack.

Grace sagged, tears spilling down her cheeks.

Ellie launched herself out of her chair and into Grace’s arms.

“You’re my mama now,” she whispered into Grace’s neck.

“Yeah, baby,” Grace said, holding her tight. “I am.”

A year later, on a bright Louisiana afternoon, the second-graders at Ellison Elementary sat cross-legged on a classroom rug while their teacher adjusted her phone to record.

“Okay,” the teacher said. “Our next student is going to share her ‘All About Me’ project. Ellie?”

Ellie May Mathers stood up, paper in her hand.

She still flinched sometimes when someone dropped a book. Loud noises made her tense. Crowded rooms overwhelmed her.

But she spoke clearly now.

“My name is Ellie,” she read, her voice steady. “I used to be very quiet. People thought I couldn’t hear. But now my ears are fixed, and I can hear music and birds and my mama’s voice.”

She glanced up.

Grace stood at the back of the room, leaning in the doorway, watching.

“I live in an apartment,” Ellie continued. “It’s small, but it’s warm, and it smells like pancakes. My favorite sound is when my mama laughs. My favorite word is ‘home,’ because now I know what that is.”

When she finished, the class clapped.

After school, with the afternoon sun slanting across the cracked sidewalks, Grace and Ellie walked hand in hand toward their car.

“Can we get ice cream, Mama?” Ellie asked.

Grace laughed, her heart full.

“We can always get ice cream,” she said. “That’s one of the perks of having a mama who’s a pushover.”

Ellie giggled.

“Miss Donna says you’re not a pushover,” she said. “She says you’re a hero.”

Grace shook her head.

“I’m not a hero,” she said. “I just did what someone should have done a long time ago.”

Ellie squeezed her hand.

“You called 911,” she said thoughtfully. “You saw the thing in my ear and you pulled it out and you called. That’s hero stuff.”

Grace remembered the smell, the sight of that packed plug in Donna’s tweezers, the red marks behind tiny ears.

She shivered.

“I called because I love you,” she said. “That’s all.”

Ellie looked up at her, serious.

“Sometimes loving is the same as saving,” she said.

Grace stopped in her tracks, overwhelmed.

“Who told you that?” she asked.

Ellie shrugged.

“Miss Patricia,” she said. “She said you loved me so much you broke all the rules.”

Grace smiled through sudden tears.

“Yeah,” she said. “I guess I did.”

They reached the car. Grace buckled Ellie into her booster seat, then paused, hand on the door.

The world was still full of kids sitting in corners. Full of teachers told to keep their heads down. Full of social workers drowning in files. Full of principal Harmons and Boyd Thornhills.

She couldn’t save them all.

But she’d saved one.

And sometimes, that was enough.

“Hey, Mama?” Ellie called from the back seat.

“Yeah, kiddo?”

“Next time you see a quiet kid,” Ellie said, swinging her feet, “you’re gonna look in their ears too?”

Grace laughed.

“I’ll start with their eyes,” she said. “And I’ll listen. Really listen.”

Ellie nodded, satisfied.

“Good,” she said. “’Cause nobody should be invisible.”

Grace started the car.

As they pulled away from the curb, she caught sight of herself in the rearview mirror—tired eyes, lines at the corners, hair scraped back in a messy bun.

Teacher. Foster parent. Single mom.

Rule breaker.

She didn’t look much like a hero.

She looked exactly like somebody’s answer to a whispered prayer.

“Ready for ice cream?” she asked.

“Ready for everything,” Ellie said.

They drove into the bright, noisy, beautiful world together.

THE END

News

“Where’s the Mercedes we gave you?” my father asked. Before I could answer, my husband smiled and said, “Oh—my mom drives that now.” My father froze… and what he did next made me prouder than I’ve ever been.

If you’d told me a year ago that a conversation about a car in my parents’ driveway would rearrange…

I was nursing the twins when my husband said coldly, “Pack up—we’re moving to my mother’s. My brother gets your apartment. You’ll sleep in the storage room.” My hands shook with rage. Then the doorbell rang… and my husband went pale when he saw my two CEO brothers.

I was nursing the twins on the couch when my husband decided to break my life. The TV was…

I showed up to Christmas dinner on a cast, still limping from when my daughter-in-law had shoved me days earlier. My son just laughed and said, “She taught you a lesson—you had it coming.” Then the doorbell rang. I smiled, opened it, and said, “Come in, officer.”

My name is Sophia Reynolds, I’m sixty-eight, and last Christmas I walked into my own house with my foot in…

My family insisted I was “overreacting” to what they called a harmless joke. But as I lay completely still in the hospital bed, wrapped head-to-toe in gauze like a mummy, they hovered beside me with smug little grins. None of them realized the doctor had just guided them straight into a flawless trap…

If you’d asked me at sixteen what I thought “rock bottom” looked like, I would’ve said something melodramatic—like failing…

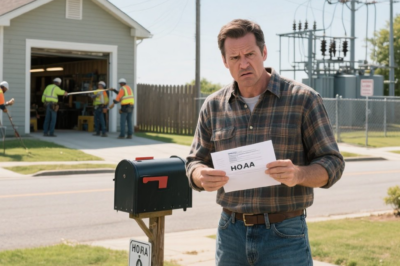

HOA Cut My Power Lines to ‘Enforce Rules’ — But I Own the Substation They Depend On

I remember the letter like it was yesterday. It came folded in thirds, tucked into a glossy HOA envelope that…

I Overheard My Family Planning To Embarrass Me At Christmas. That Night, My Mom Called, Upset: “Where Are You?” I Answered Calmly, “Did You Enjoy My Little Gift?”

I Overheard My Family Plan to Humiliate Me at Christmas—So I Sent Them a ‘Gift’ They’ll Never Forget I never…

End of content

No more pages to load