Stop acting like a nurse.

That’s what my brother hissed in my ear, his lips barely moving, his voice pitched at that perfect, poisonous level where only I could hear the words—but the officers around us could hear the contempt.

The chandelier above the ballroom flickered, crystal catching in the light of a hundred uniform ribbons and medals. The gold spilled across his dress blues, turned his captain’s bars and badges into something metallic and sharp, like the smirk he was wearing.

I felt it then—the old heat along my spine. Shame. Anger. Restraint.

Three ghosts that had lived rent-free in my body for most of my career.

I wrapped my fingers a little tighter around the stem of my champagne flute. I didn’t trust my hands to stay steady otherwise. The champagne tasted like nothing. Noise blurred around us—laughter, clinking glass, the soft swell of the orchestra in the far corner.

“Seriously, Lena,” my brother murmured, still looking forward, not at me. “You patch up cuts. You’re not a hero. Stop pretending.”

The words slid under my skin like a cold blade. Familiar. Precise. The kind of blade he’d once used to carve apart everything I trusted about myself.

I didn’t look at him.

I looked past him, over his shoulder, across the crowded ballroom.

Past colonels and majors and their wives in silk, past young lieutenants with stiff backs and wide eyes, past reporters pretending not to be reporters with their little notebooks and discreet cameras.

To the far corner of the room, near the exit, half in shadow.

Where David sat alone in his wheelchair, half shrunk into his dress blues like a boy trying to disappear. The wheelchair had been polished for the gala; the chrome edges shone. The man in it did not.

His shoulders were hunched, his hands folded loosely in his lap, the brim of his service cap low enough to shadow his eyes. People skimmed around him like he was furniture. They didn’t stare—they were too well-trained for that—but they avoided him with the unconscious flinch people reserve for reminders of mortality.

My brother snorted softly at my wandering attention.

“You still doing it,” he said. “Still collecting broken toys.”

I set my champagne on the nearest tray without drinking, turned, and walked away from him.

Not quickly. Not dramatically. Just… away. Out of his shadow, out of the little orbit of officers who’d gathered around him like satellites around a rising star.

The music shifted key, strings drawing out into something slow and dignified. The air smelled like cologne and polished wood, like expensive perfume trying to mask the sweat of men who’d once lived in sand and diesel.

I crossed the ballroom toward the corner.

David didn’t look up until I was almost there. When he did, his eyes startled the way I’ve seen soldiers startle when you touch them gently in a field hospital—like they’d forgotten what gentleness feels like and it takes them a second to recognize it.

“Colonel,” he said. His voice was quiet, his posture trying to curl smaller. “You don’t have to—”

“David,” I said, stopping beside him. “May I have this dance?”

He blinked. I could read the thoughts swirling behind his eyes as clearly as I can read a triage chart. Panic. Embarrassment. Disbelief.

“I—” he stammered. “I can’t.”

“You can,” I said. “With me.”

I didn’t ask again. I didn’t apologize. I simply moved behind his chair, thumbed off the brakes, and began to roll him gently toward the dance floor.

The nearest couple broke apart, caught off guard. Then the next. A narrow path opened in front of us, the crowd parting like a tide, faces turning, curiosity rising like static.

Someone snickered. Someone else whispered. Someone’s camera phone appeared and then disappeared just as fast when they remembered the four-star general in the room.

At the edge of the parquet dance floor, I swung around to face David again.

“Put your hand here,” I said, placing his right hand on my forearm, my left hand resting lightly on his shoulder. “We’ll improvise the rest.”

“I’m going to crush your toes,” he muttered, but there was a hint of a smile in it.

“I trust my reflexes,” I said.

The orchestra, professional enough not to miss a beat for anything shy of a fire alarm, slid into the second verse of some old standard every military ball seems required by law to play. The tempo was slow, forgiving.

I guided his chair onto the floor, my heels clicking. He moved with me, tentative at first, then more sure as he realized the wheels weren’t going to betray him.

We turned.

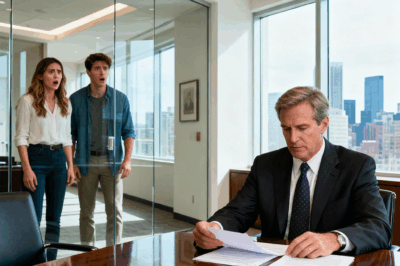

And that’s when I saw the general.

General Henry Markham—four silver stars glittering on his epaulets, jawline carved by forty years of command, shoulders still straight despite everything—stood at the far end of the dance floor, frozen.

His gaze locked on us.

On his son’s wheelchair. On my hand on David’s shoulder.

People around him shifted, whispered, but he didn’t move.

Then he did. Slow at first, then faster, cutting across the floor like a man moving toward something he’d thought was lost.

The air in the room changed. It thickened. Conversations hiccuped and trailed off. Reporters lifted cameras. The orchestra kept playing, because professionals play through anything.

General Markham stopped right beside us.

“Colonel,” he said.

His voice was thick. Not with alcohol. Not with anger.

With something else.

“Sir,” I said. I straightened a fraction, but I didn’t step away from David.

The general’s gaze flicked from me to his son and back again.

“Colonel,” he said quietly, as if the whole room weren’t leaning in. “You’ve just saved my son’s life.”

Behind me, I heard glass clink against marble. Somewhere to my left, my mother gasped. My father’s breath caught. My brother went stone still.

And that was the moment.

The moment my revenge truly bloomed.

I wasn’t born wanting revenge.

I was born wanting to keep my brother alive.

Back before rank and ribbons and pin-perfect uniforms, we were just two kids in a split-level house in Colorado with orange shag carpet and wood paneling that never stopped smelling like stale cigarettes and Lemon Pledge.

He was two years older and six inches taller and never let me forget either. I followed him anyway.

We climbed the same trees, scraped the same knees. When he took a dare and dove off the culvert into the ditch and split his chin on a rock, I was the one who held his face together with Band-Aids and pressure until Mom got home.

When the neighborhood bullies tried to take my bike, he came at them like a thrown brick. He got his nose bloodied and his lip split. I patched those too, sitting on the back steps with a dishcloth and a Dixie cup of water.

We made a pact once, under a blanket with a flashlight, that feels almost laughable now. We linked our pinkies, serious as heart attacks.

“You always got my back,” he said.

“You always got mine,” I replied.

We said it like a prayer. Like a promise we didn’t understand yet.

We grew up on war movies and recruiting posters. Dad had been Army artillery, then spent the rest of his life pretending to be fine about the fact that he never made it past E-6. Mom worked night shifts at the grocery store, day shifts at home smoothing over the rough edges of a man who’d once had people jump at his orders and now jumped at every lost remote.

Our house spoke in acronyms. PCS, TDY, MOS. We saluted the flag in the living room before Dad would let us open Christmas presents. We folded laundry like uniforms before we ever wore them.

So of course we both signed up.

He wanted infantry. Boots in the mud, gun in hand, chest out. He wanted to be the one in the posters.

I wanted medicine.

I’d seen what it did to people when nobody knew how to help. The kid three doors down who stopped breathing when his asthma got bad and our neighbor down the street did chest compressions wrong. The guy at Dad’s worksite who lost three fingers because nobody thought to apply a tourniquet.

Impact, that was what I craved. Not glory. Not whatever passed for fame in the tiny orbit of an Army base.

Impact.

We both got what we wanted, at first.

Basic was hard but not impossibly so. Officer Candidate School was a slog. Commissioning felt like being handed a script and told, Congratulations, you’re one of the principal characters now. His branch insignia was crossed rifles. Mine was a caduceus.

He went to Ranger School. Airborne. All the hard badges that look so pretty on a Class A.

I went to advanced training in trauma, burn care, surgery. Learned how to do impossible things with not enough hands and less sleep. Learned how to give bad news without breaking apart.

Our paths crossed sometimes on the same installations. Holiday block leaves, brief TDYs. We’d meet up in the officers’ club or at some awful bar off post, trade stories we half-believed about our respective worlds.

At first, he respected what I did. Or at least, he pretended to.

“You’re the one who keeps the idiots alive,” he’d say, popping a fry in his mouth. “We break it, you fix it.”

Then he started getting promoted on schedule. “Captain Hart.” Company command. People snapped to when he walked into a room. His voice lowered, got that command edge. He liked it.

I got promoted too. First lieutenant. Captain. Major. My promotions came from nights in ORs and emergency tents, not from passing APFTs by a narrow margin and knowing which colonel preferred Scotch.

At first the distance between us just felt like different branches, different jargon.

Then it felt like something sharper.

The first sign was subtle enough I almost missed it.

A rumor, floating in the background like a bad smell.

“Colonel Hart cut corners on a triage.”

“Colonel Hart discharged a patient too early.”

“Colonel Hart overrode a surgeon’s plan.”

Nothing concrete. Nothing trackable. Grumblings in hallways, half-heard conversations that went quiet when I walked in.

I shrugged it off as the usual resistance to a woman with rank in a field that still thought of nurses as the ones who fetched, not the ones who decided.

Then my promotion packet from Major to Lieutenant Colonel came back “on hold.”

No explanation. No commentary. Just… held.

“Some anonymous concerns were raised,” my CO said, not meeting my eye. “It’s probably nothing. Paperwork. You know how it is.”

I did know. I knew paperwork like I knew the weight of a human heart. It didn’t move without someone pushing.

Then came the hearing.

Not a court-martial. Just an inquiry. Just six officers in a room with folders in front of them and my entire record spread out like a patient on a table.

“Colonel Hart,” the chair said—the first time anyone had called me that; my rank had just pinned on—“there have been several anonymous complaints regarding your clinical judgment.”

Anonymous.

“In one instance,” he went on, “you allegedly discharged a soldier with abdominal pain who was later found to have a ruptured appendix.”

“I discharged him with normal vitals and a normal exam,” I said. “He declined a CT because he didn’t want the radiation and said he had to get back to formation. I documented all of that. When his pain worsened, he came back and we took him straight into surgery. He recovered.”

“In another complaint,” the chair continued, “you allegedly prioritized an officer over an enlisted soldier during mass-casualty triage.”

“That’s a lie,” I said, before I could stop myself.

The room went still.

“Colonel,” the chair said, warning in his tone.

I took a breath. “Sir,” I said more carefully, “that is not an accurate representation of the event. We triaged by injury severity. The officer in question happened to have a penetrating chest wound. The enlisted soldier had a broken wrist.”

“And yet,” another officer said, tapping a paper, “we have these anonymous reports.”

Anonymous. Precise. Written by someone who knew the language, the codes, the little details that gave a lie the taste of truth.

I walked out of that room with my rank intact but something inside me sliced open. Not because they’d questioned my decisions. That came with the job. Because of the anonymity.

I don’t like shadows. I spend my days hauling people out of them.

So I traced the threads.

I pulled at little things. Who had access to which records. Who had reason to resent which decisions. Who used which phrases in their everyday speech.

Each anonymous complaint used the phrase “exhibited quiet arrogance.”

So did my brother.

“You’re so quietly arrogant, Lena,” he’d said once, half a beer in, annoyed that I’d corrected his misquote of a regulation. “Like you think you’re better than the rest of us because you read more.”

In the complaints, they mentioned specific dates, meetings, exchanges in hallways only a handful of people had been present for. My brother had been present for every single one.

You didn’t need to be a detective to see the line.

My brother, the boy who’d held a dishcloth to his busted nose while I cleaned it, the man who’d stood next to me when we pinned on our butter bars, had been carving me open from behind.

I didn’t break.

I didn’t scream. I didn’t storm his quarters and demand answers. I thought about it. More nights than I can count, staring at the ceiling of my BOQ room, hand curled into a fist.

I didn’t.

Instead, I did what I do best.

I assessed.

I planned.

Revenge doesn’t require rage.

It requires patience.

To understand how to dismantle my brother, I needed to understand what he cared about more than hurting me.

Ambition.

He chased it like a dog chases anything that runs. New assignments. New schools. New opportunities to be seen.

By the time I hit colonel, he was a captain with his eyes on major and beyond. He wanted command of troops in combat, sure—but what he really wanted was proximity to power.

Specifically, to General Markham.

Markham was everything Dad had wanted to be and never reached. West Point. Ranger Regiment. Multiple deployments with his name in the papers. Photos on the front page—him in sunglasses, headset, hand over his mouth, pointing at maps.

When Markham took over U.S. Northern Command, my brother started talking about him like he was Moses.

“If I can get on his staff, that’s it,” he said once over coffee in the DFAC, eyes bright. “He only takes the best. A couple years as his aide, and it’s straight to brigade command, easy.”

“That’s not how it works,” I said.

He rolled his eyes. “You wouldn’t understand,” he said. “You’re not in the real Army.”

The “real Army.”

The one with guns and salutes and press conferences. Not the one with scalpels and sutures and chest tubes.

I filed that sting away with the rest.

Then the accident happened.

Not to my brother. Not to me.

To David.

David Markham had never wanted to be his father.

That’s what he’d told me, the first time we really talked. Not the first time we met—that had been weeks earlier when I’d saluted the general and nodded politely at the son wheeling himself behind him like a shadow.

The first time we talked was in the PT gym.

I was there because old habits die hard. You don’t keep up with combat medics half your age if you let yourself slack. The Army physical fitness test wasn’t going to crush me at forty-two. I’d seen too many colonels let rank replace muscle. I had no interest in becoming one of them.

He was there because his father had finally bullied him into showing up.

He sat by the parallel bars, hands clenched on the wheels of his chair, jaw set. His PT, a cheerful sergeant with a clipboard, tried to coax him into a transfer.

“You’ve done this before, sir,” she said. “You can do it again.”

“I’m not your sir,” he muttered. “I’m your cautionary tale.”

I’d been on the treadmill, headphones in, pretending not to listen. You learn to give people privacy even in public spaces when your entire job is watching them at their worst.

But something about the way he said it snapped a wire in me.

I hit stop, pulled the headphones down, and walked over.

“Mind if I cut in?” I asked the PT.

She blinked, then nodded and stepped back. “Yes, ma’am.”

David glanced up, surprised. “Colonel,” he said stiffly. “You don’t have to—”

“I know,” I said. “But I want to.”

He scowled. “Why?”

“Because you’re hogging the bars,” I said. “And if you’re going to sit here feeling sorry for yourself, you might as well move three feet to the left.”

It was a calculated provocation. Not cruel. Just sharp enough to pierce the sulk.

His eyes flashed. “You don’t know anything about—”

“About waking up in a hospital not sure what parts of you still work?” I said. “About having your life plan ripped up in front of you? About people treating you like a symbol instead of a person? You’re right. I know nothing.”

He stared at me. His PT hid a smile behind her clipboard.

“You used to run track,” I said. I’d seen the photos in the base paper when his father took command. Young man, state champion, in a uniform two sizes too big, proud as hell. He looked shorter now. Smaller.

“Yeah,” he said cautiously.

“How many miles a week?” I asked.

“Forty,” he said. “Sometimes fifty.”

“Then you know how this works,” I said. “You put in the reps. You don’t get those legs back, but you get something else. Shoulders, arms, lungs. Or—or you stay in the chair and let it eat you.”

He swallowed.

“Your call,” I said. “I’ve got time to spot you.”

He glared at me for a full ten seconds. Then he blew out a breath.

“Fine,” he said. “But I’m doing it myself. No pity lifts.”

“Good,” I said. “I hate pity.”

He transferred to the bars like his life depended on it. His arms shook. Sweat beaded on his forehead. The PT hovered. I stood close enough to catch him but not so close he’d feel trapped.

He made it three steps the first day.

The second, he made it five.

The third week, he made it to the end of the bars and back, collapsed into his chair, and laughed—a rusty sound like someone trying out joy for the first time in a while.

We talked. Not about the accident itself—that was still a raw wound—but about everything around it.

About how everyone started calling him “brave” for going to the commissary, like he’d climbed Everest. About how strangers put their hands on his wheelchair handles without asking, like they owned him. About how his father’s eyes stabbed him with guilt every time they met, even when the general didn’t say a word.

“They treat me like a symbol,” he said once, staring at his hands. “The Resilient Warrior. The Inspirational Story. I’m still me in here. I’m just… less useful.”

“Bullshit,” I said.

He looked up, startled.

“You’re not less useful,” I said. “You’re differently useful. And if anyone can’t see that, that’s their limitation, not yours.”

“You sound like a recruiting poster,” he said, but there was no bite in it.

“I sound like someone who’s watched guys with half their intestines gone learn how to dance at their daughter’s weddings,” I said. “You’re not the first person to lose something important, David. You’re just the one everyone’s staring at right now.”

He swallowed hard.

“Why do you do this?” he asked once, weeks later, when we were spotting him on a rowing machine instead of the bars. “You’re a colonel. Don’t you have better things to do than babysit a broken staff sergeant?”

“First,” I said, “you were a staff sergeant. Now you’re the general’s son. People would kill for that kind of access.”

He snorted.

“Second,” I went on, “I’m not babysitting. I’m training. There’s a difference.”

“Training me for what?” he asked.

“Life after impact,” I said.

He frowned. “What does that even mean?”

“Everything hits you at some point,” I said. “A bullet, a bomb, a drunk driver, a diagnosis, a betrayal. The impact isn’t the end. It’s what you do after that counts.”

He was quiet for a long moment.

“Somebody do that for you?” he asked.

I thought about my brother. About anonymous complaints and quiet knives.

“No,” I said. “But I wish they had.”

The general noticed.

He always noticed everything, even when he pretended not to.

He noticed when David started showing up to PT on his own instead of being dragged. He noticed the new calluses on his son’s palms, the way his shoulders filled out again, the less-fake smile at dinner.

He noticed the way I talked to his son like a soldier, not a mascot.

“Colonel Hart,” he said one day, catching me outside the gym. “Walk with me.”

We walked.

He was a head taller than me, his stride measured, hands clasped behind his back. The hallway smelled like floor wax and institutional coffee.

“I appreciate what you’re doing for David,” he said without preamble.

“I’m doing my job, sir,” I said.

“Don’t give me that,” he said. “Your job is to run a hospital. This is… extra.”

“I don’t do anything halfway,” I said.

He looked at me sideways. “I’ve read your file,” he said. “Anonymous complaints and all.”

My stomach tightened. “Yes, sir,” I said carefully.

“They were… interesting,” he said.

“Sir?” I asked.

“Interesting in how they didn’t line up with anything else in your record,” he said. “Interesting in how they were written.”

I swallowed.

“And interesting in who wrote them,” he said.

He stopped walking. Turned to face me.

“I’ve been in this business a long time, Colonel,” he said. “I’ve seen officers kneecap each other for less than a parking space. I know how to read writing patterns.”

“Sir—” I began.

He held up a hand.

“You don’t need to say anything,” he said. “I already know.”

He didn’t say my brother’s name. He didn’t have to.

“You could have filed counter-complaints,” he went on. “You didn’t. You could have gone to IG. You didn’t. You just kept doing your job. Kept showing up for my son.”

He looked toward the gym door where David’s laugh echoed faintly.

“That matters,” he said simply.

“Thank you, sir,” I said.

He nodded once. “We have a gala coming up,” he said. “You’ll be there.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

He looked back at me, eyes sharp and oddly soft at the same time.

“Wear your dress blues,” he said. “With every ribbon you’ve earned. Let people see what quiet impact looks like.”

The gala wasn’t for me. Not officially.

On paper, it was a fundraiser and awards ceremony. The general would give a speech about readiness and resilience. Some big donors would get their pictures taken. A handful of officers would get coins and plaques.

There would be music, fancy food, enough alcohol to loosen tongues just past protocol.

My brother would be there.

He’d finagled his way onto one of Markham’s working groups, orbiting the general’s staff like an anxious planet. He loved events like this. Opportunities to be seen. To shake hands. To slip into photos that would look good on his next promotion packet.

We hadn’t spoken much since the anonymous complaints surfaced.

He’d texted once, after the hearing.

Don’t take it personally, he’d written. It’s just how the game is played.

I hadn’t replied.

I spent the week before the gala preparing.

Not just my uniform—though that mattered. I had my blues pressed, my ribbons rechecked. Combat Medical Badge. Meritorious Service Medals. NATO ribbon. The little things most people’s eyes skated over while they counted the shiny things on combat arms uniforms.

I prepared David.

“Why would I go?” he asked when I brought it up. “So everyone can stare and whisper, ‘oh, there he is, the tragic cripple son’?”

“Because it’s your father’s event,” I said. “Because he’s proud of you. Because hiding in your room for the rest of your life isn’t a strategy, it’s surrender.”

He glared.

“Also,” I added, “because there will be good food, and you can run over at least three people’s toes and I’ll blame it on your brakes.”

He snorted. “That’s evil, Colonel.”

“I’m a medical officer,” I said. “We’re all a little evil. Comes with the job.”

In the end, he agreed.

We went over the plan. Where he’d sit. When he’d take his meds. How long he’d stay before he bailed if it was too much.

The one part I didn’t tell him about was the dance.

Not because it was staged—not exactly. Because I didn’t want him to feel like a prop.

I didn’t want anyone to be a prop, not even in my revenge.

Even my revenge had to be… clean.

The night of the gala, the ballroom glittered.

Crystal chandeliers. Floor-length tablecloths. White-gloved servers navigating through clusters of officers like they were running a combat obstacle course in reverse.

The band in the corner played Sinatra-standard-adjacent jazz. The air hummed with the layered noise of people who all knew they were being watched.

I arrived on the early side, checked in, let the photographers take one obligatory picture holding a faux awards plaque for the hospital’s latest performance metrics.

My brother arrived twenty minutes later.

I felt him before I saw him.

There’s a particular energy some officers carry into a room when they’re on the hunt—backs straight, smiles wide, eyes scanning for anyone with more rank. They’re not there to relax. They’re there to network.

He walked in wearing his own dress blues, chest full of badges. His Ranger tab and Airborne wings sat above his left breast pocket like punctuation marks on a story he never stopped telling.

He spotted me. Smiled. Not warmly.

“Lena,” he said, threading through the crowd. “You clean up nice. Almost looks like you belong.”

“Captain,” I said.

He leaned in, his breath warm against my ear.

“Remember,” he murmured, “you’re just a nurse with delusions of grandeur. Try not to embarrass yourself.”

I smiled like his words were a joke.

“Oh, don’t worry,” I said. “I’ve had years of practice not embarrassing you.”

He laughed, slapped my shoulder a little too hard, and moved on, already angling toward a cluster of colonels.

I breathed slowly, counting in and out. One, two, three, four. One, two, three, four.

The general made his entrance with less fanfare than the ballroom wargamers might have expected. No trumpet. No booming announcement. Just a man in four stars walking in with his wife on his arm and his son at his side.

People parted for him without being asked. He nodded, smiled, shook hands.

His eyes found me across the room. A small tilt of his head. A silent acknowledgment.

I nodded back.

I watched David roll himself to a table near the back, angled so he could see but not be in the center of anything. Old habits die hard. Hide in the periphery, stay small, don’t draw fire.

My brother drifted toward the general like smoke toward a vent. He laughed a little louder, smiled a little brighter, made sure his path would intersect Markham’s.

He was almost there when I stepped in.

Not between them. Just… out of his orbit. Away from his line of sight.

That’s when he leaned in and said it.

“Stop acting like a nurse,” he hissed. “You patch up cuts. You’re not a hero. Stop pretending.”

The words landed. The ghosts rose.

Shame, whispering that maybe he was right. Anger, roaring that he was not. Restraint, holding the first two back with steady hands.

I didn’t hit him. I didn’t scream.

I set my drink down.

I turned away.

I walked toward the corner where the general’s son sat alone, shrinking into his uniform.

The dance happened.

The general crossed the floor. He spoke. Cameras flashed. Applause rose like thunder cracked in half.

“Colonel, you’ve just saved my son’s life,” he said, voice thick enough that even the reporters put down their cameras for a second.

He wasn’t talking about the wheelchair. He knew I couldn’t give David back what he’d lost. He was talking about something else. The spark in his son’s eyes. The way his shoulders weren’t curled quite so far inward. The fact that he was on a dance floor in front of people instead of in his room with the door locked.

I felt the weight of the moment settle over my shoulders like a cloak I hadn’t asked for but wouldn’t shrug off.

Behind me, my family froze.

Dad’s face was a study in confusion and reluctant pride and something darker. Mom’s mouth hung open. My brother’s smile flickered.

The general straightened.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, his voice shifting from father to commander. “If I could have your attention for a moment.”

The orchestra faded out. Conversations died. All eyes turned toward the center of the floor.

“I wasn’t planning to speak now,” Markham said. “But I think it’s appropriate.”

He rested a hand on David’s shoulder. His other hand brushed my sleeve for a fraction of a second, steadying me as much as himself.

“Many of you know my son’s story,” he said. “Some of you have read about it in the paper. Fewer of you know the truth of what it is to sit where he sits. Fewer still know what it is to walk beside him.”

He looked at me.

“Colonel Hart has done that,” he said simply. “She has treated my son not like a burden, not like a symbol, but like a soldier. She has pushed him when he wanted to give up, listened to him when he wanted to stay silent, and reminded him that his life did not end the day of his accident.”

He could have stopped there. It would have been more than enough.

He didn’t.

“I’ve also had the occasion,” he went on, his tone cooling, “to review some… anonymous complaints regarding Colonel Hart’s performance.”

You could feel the air change again. Officers shifted. Reporters perked up.

“Those complaints,” he said, “were written by someone who knew just enough about her to be dangerous. They alleged carelessness. Favoritism. Poor clinical judgment. They were lies.”

He let the word hang.

“Lies,” he repeated. “Carefully crafted, malicious lies designed to tarnish the record of one of the finest officers I’ve had the privilege to serve with.”

My chest tightened.

“I have seen Colonel Hart in the field,” he said. “I have seen her stand knee-deep in blood and mud, hands steady, voice calm, saving men who thought they were already dead. I have seen her log fourteen-hour shifts in the OR and then sit with a private’s wife at three in the morning so she wouldn’t have to hear the word ‘amputation’ alone. Her record is not merely ‘not what those complaints suggest.’ It is immaculate.”

His eyes hardened.

“Unfortunately,” he said, “the same cannot be said for the officer who authored those complaints.”

You could have heard a pin drop.

“Captain Hart,” the general said, turning his gaze across the floor. “Step forward.”

My brother stiffened like someone had poured ice water down his spine. For a heartbeat, I thought he might pretend not to hear. Then he remembered there were cameras. He straightened, plastered a smile over his face, and stepped toward the general.

“Sir,” he said. “It’s an honor—”

“Spare me the pleasantries, Captain,” Markham said.

The cold in his tone could have stopped the orchestra’s heart if it had still been playing.

“I have copies,” the general said, “of every anonymous complaint. Every forged report. Every email you sent under assumed names from on-post servers. Colonel Hart has provided them to me, along with logs from CID and the Inspector General’s office tracing the origin of those messages.”

He glanced at me, just for a fraction of a second, and in that look was the acknowledgment that I had given him the evidence. Quietly. Methodically. Without fanfare.

“I have tolerated many things in my career,” Markham went on. “Incompetence, which can be trained out. Arrogance, which can sometimes be humbled. But I do not tolerate officers who deliberately sabotage their comrades to advance their own careers.”

Color drained from my brother’s face.

“Sir, I think there’s been a misunderstanding,” he began.

Markham lifted his chin.

“The only misunderstanding here, Captain,” he said, “was yours, when you assumed your actions would never see daylight.”

He took a breath.

“Effective immediately,” he said, “you are removed from consideration for any position on my staff. I will be forwarding my findings and the supporting documentation to your chain of command and to the appropriate boards with my recommendation that your fitness for continued service be evaluated.”

He didn’t say “career over.” He didn’t have to.

Everyone in the room heard it.

My brother’s mouth opened and closed. He looked around, searching for someone—anyone—to jump in and save him. Dad took a step forward, then stopped, torn between paternal instinct and fear of a four-star’s glare.

“Sir,” my brother tried again. “With all due respect—”

“You have shown none,” Markham cut in. “Not to your sister. Not to your oath. I suggest you leave before you compound this humiliation with further poor judgment.”

My brother staggered backward. The room seemed to widen around him, people unconsciously edging away as if toxicity were contagious.

For the first time since childhood, he was the one bleeding from cuts he’d carved.

Not physical ones. Deeper.

He turned, shoved his way through the crowd, and vanished toward the exit.

The general looked back at me and David.

“I’m sorry to drag this into your moment,” he murmured.

I shook my head. “It was never mine alone, sir,” I said.

He smiled faintly.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, raising his voice. “I suggest you pick a partner and follow my son’s example. You’re not getting out of dancing that easily.”

The tension in the room broke on a ripple of nervous laughter. The band, sensing the cue, slid back into music. Couples stepped hesitantly onto the floor again.

Life, as it always does, began to flow back in.

Later, when the speeches were done and the donors had drifted away and the reporters had filed their stories, the ballroom emptied.

The chandeliers dimmed. Staff cleared plates, folded chairs. The band packed up.

I stepped out onto the balcony.

The night air was cool, edged with the smell of damp stone and distant traffic. The base lights glittered below like a constellation drawn by someone who believed in order.

I leaned on the railing, dress blues creaking slightly at the seams, breathing in air that felt clean for the first time in years.

I wasn’t triumphant.

People imagine revenge as fireworks, as fist-pumps, as slow-motion walks away from explosions. Maybe it is for some.

For me, it was… release.

Like finally exhaling after holding my breath for a decade. Like unshouldering a ruck after a thirty-mile march and realizing you no longer have to carry what’s inside.

Footsteps sounded behind me.

I turned, half expecting my brother.

It was David.

He rolled his chair out onto the balcony, the small bump of the threshold barely jostling him.

“You disappeared,” he said.

“Occupational hazard,” I said. “I do that in ORs too. Finish the job, slip out the back.”

He snorted softly.

“My dad’s been looking for you,” he said.

“He knows where to find me,” I said. “He has my number.”

“He wants to give you a medal or something,” David said. “For tonight.”

“I have enough metal,” I said. “My jacket’s already heavy.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“What he said,” he went on carefully, “about… about your brother. I didn’t know.”

“Most people didn’t,” I said. “By design.”

“Why didn’t you say anything?” he asked. “Before now?”

I looked out over the base lights, the faint outline of the mountains beyond.

“Because if I’d shouted when it first happened,” I said, “everyone would have heard ‘family drama’ instead of ‘professional sabotage.’ Because I needed to be sure. Because I wanted him to have enough rope to hang himself rather than just bruise his neck.”

“That sounds… kind of dark,” he said.

I smiled faintly. “Revenge doesn’t require rage,” I said. “It requires patience.”

He laughed once. “You sound like a villain,” he said.

“I’m a colonel in the medical corps,” I said. “We’re all villains in somebody’s story. Usually the one where they thought they were indestructible.”

He sobered.

“I’m glad you didn’t… you know… leave,” he said. “When they delayed your promotion. When the rumors started. I’ve seen a lot of good people bail over less.”

“Leaving would have given him exactly what he wanted,” I said. “I’m stubborn. Comes from being the younger sibling.”

We stood—or sat—there for a while, listening to the wind.

“Thank you,” he said finally.

“For what?” I asked.

“For dragging me onto that dance floor,” he said. “For making my father see me. For… showing everyone I’m not just a tragic headline.”

“You did that,” I said. “I just unlocked your brakes.”

He huffed a small laugh.

“Will you—” he hesitated. “Will you still come to PT next week? Or are you going to vanish into some high-speed assignment now that you’re the general’s hero?”

I thought about it. About offers that might come. About being on panels and committees. About the way people’s eyes would change when they looked at me now, seeing not just a hospital commander but the woman who’d publicly weathered and exposed a sabotage attempt and gained a four-star’s praise.

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll be there. Six a.m. Don’t be late.”

He smiled, the kind that reached his eyes this time.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

He rolled back inside. The door swished shut.

I stayed another minute.

Thinking about my brother.

I knew he’d come find me eventually. That he’d want to spit venom in private where it was safe. Or beg. Or justify. Or some mixture of all three.

He never did.

He put in for a transfer instead.

I heard through the grapevine that he got shipped to some nowhere post in the middle of the desert with no staff billets, no command track, no path to Markham’s orbit. His promotion to major stalled. The investigation into his complaints simmered in the background, ready to boil if he stepped out of line again.

I didn’t feel joy at that.

I felt… symmetry.

He had mistaken my silence for weakness.

He forgot silence can be strategy.

He forgot quiet hands can still hold power.

He forgot what I will never forget:

Some of us don’t need to raise our voices to be heard.

We just have to choose the exact right moment to speak.

I straightened, adjusted my jacket, and went back inside, my heels clicking against the marble like a drumbeat.

Not marching into a war.

Walking into my own life.

THE END

News

MY SON SAID I WAS “TOO OLD AND BORING” FOR THEIR CRUISE — SO I LET HIM KEEP HIS PRIVATE FAMILY VACATION… WHILE I QUIETLY TOOK BACK EVERYTHING HE THOUGHT HE OWNED.

My son and daughter-in-law wouldn’t let me go on their cruise: “Mom, this trip is just for the three of…

Siblings Excluded Me From Inheritance Meeting – I’m the Sole Trustee of $400M…

The first lie my siblings ever told themselves about me was that I should be grateful. Grateful that our…

My Coworker Tried To Sabotage My Promotion… HR Already Chose ME

When my coworker stood up in the executive meeting and slid that manila folder across the glass conference table, I…

My Sister Said, “No Money, No Party.” I Agreed. Then I Saw Her Facebook And…

My name is Casey Miller, and the night my family finally ran out of chances started with one simple…

Emily had been a teacher for five years, but she was unjustly fired. While looking for a new job, she met a millionaire. He told her, “I have an autistic son who barely speaks. If I pay you $500,000 a year, would you take care of him?” At first, everything went smoothly—until one day, he came home earlier than usual and saw something that brought him to tears…

The email came at 4:37 p.m. on a Tuesday. Emily Carter was still in her classroom, picking dried paint…

CH2 – They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle

On July 23, 1943, at 0600 hours near Gela, Sicily, Private First Class Jacob “Jake” Henderson leaned over the open…

End of content

No more pages to load