Part I

The day we buried my brother, the sun came out like it had been paid to. It turned the black ribbon on his portrait into a bright slash and warmed the marble steps outside Graceview Chapel until they felt disrespectful under my heels. A breeze lifted the edges of the floral sprays and carried the smell of lilies over the crowd, sweet and heavy in a way that made my throat itch. People like to say funerals are for the living. Sometimes I think they’re for the weather.

Tyler’s colleagues arrived in their scrubs and white coats, the body language of the hospital still on them—pagers clipped, posture ready. They stood in clusters on the lawn and spoke in low tones the way people do when they’re used to bad news arriving in the middle of lunch. Every now and then, one of them would break and laugh—too loud, too sudden—at a story about my brother and a midnight surgery or an inside joke from the break room. I didn’t mind. Tyler would have liked it. He didn’t trust silences that carried the smell of formality.

My mother moved through the crowd with a Kleenex wadded in her fist and a faraway look, pausing every few feet to accept a hug as if each one were a prescription she’d promised to fill. My father—retired accountant, lifelong believer in the gospel of receipts—stood sentinel near the chapel doors, gripping the program until it left ink on his palm. He kept nodding to people, his mouth a line, his eyes a map no one could read.

“Are we ready?” the funeral director murmured, his voice shaped like carpet.

We were not, but the chapel was, and funerals obey schedules. Inside, the air-conditioner hummed. The photo montage—our skinny-kneed childhood, Tyler’s smug med school grin, a blurred shot of him in an OR skullcap with that little smile he wore when a challenge had been properly met—played on loop. The organist, a woman in a navy cardigan who looked like she had opinions about casseroles, hovered over the keys and watched our row as if grief were something she could accompany.

That’s when Selena strutted in.

She wore black, but only technically—in the way a dress from a glossy ad if you squinted could be called black. It had a sheen to it that suggested a party had been going on much longer than it should have. A pair of sunglasses sat on her head like a tiara. She pulled them down with one finger the way actresses do when they want the audience to have the pleasure of noticing them twice. Her mouth was painted the kind of red that announces its own existence.

“Babe,” she said to my brother’s portrait, the vowel long, the syllable shameless. She touched the frame like it might be warm.

I didn’t go to her. I stayed with the family row like a soldier on duty. When she drifted over, it wasn’t to us. She scanned the room until she found her mark—people. She wanted them to notice how she hurt.

“Oh my God,” she said to no one and everyone, dabbing nothing from the corner of her eye. “He promised me we’d be married by the end of the year.”

The nurses, gathered just behind us, shifted as a unit. They were here in little knots, mostly women, hair pulled back with pens tucked behind ears, a few of the men with stubble they hadn’t had time to shave. One of them, a tall guy with a face that looked like it had been assembled with straightforward parts, caught my eye and gave the smallest nod. It steadied me.

The service was beautiful in the way that word gets used at events that last an hour and leave you tired for a week. The chief of surgery told the story about the time my brother fell asleep standing up between cases and left a forehead print on a glass door. A scrub nurse shared how he brought donuts on the third Friday of each month without fail and remembered recipes from their potlucks. I stood and read a paragraph I’d printed on card stock and then held as if it deserved two hands—that he had been a show-off on a tricycle, a terror with a magnifying glass and ants, that he’d taught me to parallel park by having me back up to the curb and then had the nerve to clap like a coach.

What I didn’t mention was the conversation we had three weeks before he died—the one that started as a rant about a cardiovascular device manufacturer and ended with him rubbing his eyes and saying, “You know, sometimes I have to buy things that make it feel like all of this is worth it, even if it’s just for the night.” The way he said buy things, like he was confessing a habit and asking for permission to keep it.

After the benediction, we filed past the portrait the way tradition demands, some people touching the frame the way a person tests a fence. Selena planted herself near the foot of the casket like a greeter. As people peeled off to the reception hall, she stepped into their path one by one the way a fundraiser does at a gala.

“He wanted to marry me,” she repeated to anyone who paused long enough. “We were so in love.”

“He told me he was getting his affairs in order,” she said to Mrs. Ortega from billing, as if that sentence had a one-note melody.

“He took me to Le Cygne last month, the private room,” she said to Dr. Hirsch, who nodded the way men nod when they’re memorizing a story for later.

I moved to go around her. She stepped into my space the way you block someone in a crowded bar. “When do we meet with the lawyer?” she asked, breath sweet and sour, the smell of canned peaches, “I don’t want to sit around while the hospital picks through his estate.”

For a second, I didn’t understand the words. Death lifts people into strange altitudes; the air is thin up there. “I’m sorry?” I said, because I had been raised to say it when I didn’t know what else to do.

“The will,” she said, impatient now. “His money. The house, the car, the accounts. Tyler wouldn’t want me waiting.”

Two of the nurses behind me exchanged a look and didn’t hide their smiles. The tall nurse—later I would learn his name was Miguel—made a soft sound that could have been a cough.

My father stepped forward, his calm like a jacket he’d put on. “Do you truly not know?” he asked Selena, voice steady.

She crossed her arms. “Know what?”

My hand moved on its own, the way heat makes air move over pavement, the way a thought turns into a muscle before you can vote on it. Miguel caught my wrist before it reached her cheek. His grip was firm and there wasn’t a hint of play in it.

“Not here,” he said, quiet, and a nurse a few paces away laughed once—an actual laugh, like someone had said something funny and we had permission.

Selena recoiled like a cat. She looked from my father to me to Miguel and then back to the flowers, needing an audience and not finding one.

“Did the doctor leave any inheritance behind?” another nurse asked from the safety of professional curiosity. “Your family should know.”

I turned toward the voice and found myself looking at three faces—the women who had touched my brother’s hands more hours than I had in the last year. They looked tired and brave and a little wary of Selena’s performance art. It was the kindest attention I’d gotten all day.

My father inhaled and then exhaled like a math problem he could show his work for. “Not in the way you think,” he said.

“Tyler made arrangements,” I said to Selena, because if we were going to do this in a church hallway with a reception table of butter mints and coffee brewing in the distance, we might as well do it clean. “He set aside money for me—ten million yen—for my wedding fund.” I heard someone near us murmur the exchange rate in an American drawl—that’s, what, around seventy grand?—and saw one of the anesthesiologists, a woman in green scrubs, nod like she appreciated arithmetic. “He gave some smaller gifts through the years. He gave… experiences, too.” I let the word sit because it held a lot—hotels that took your breath with their prices, restaurants that made you whisper the names of the dishes like you didn’t want to scare them away. “And the rest—what remained—he donated to the hospital.”

The silence that followed wasn’t prayerful. It was the sound of a machine shutting down.

“You’re lying,” Selena said, too fast.

“Tyler wasn’t a hoarder of money,” Miguel said. His hand released my wrist. “He worked. He spent. He shared.”

“He had a talent for giving people a night,” another nurse—Sophie, I’d learn—said, and her voice softened with a memory I wanted to borrow.

Selena’s mouth worked like an engine that had been promised gasoline and was getting water. “But the mansion,” she said, halfway to sobbing now. “The condo. The car. The… the watch.”

“Leased, sublet, financed,” my father said, matching the rhythm of each word to an invisible ledger. “Debt alongside assets. Inheritance includes liabilities.”

A nervous laugh rippled through the ring of hospital friends—it’s a line someone makes when they’re trying to lighten the moment and it lands because the punch has already been thrown.

“His last act of giving was here,” the chief of surgery said, stepping up like a chorus finally arrived. “He created a fund. Research. Patient care. It will carry his name and then not have to. It will keep working when none of us are on call. It was the kindest kind of arrogance—believing your money can do more than your one pair of hands.”

Miguel bent toward me. “He told me—” he said, voice pitched just for my ear. “If anything ever happens, make sure my sister gets home before the storm starts. He made a list. Your name was first.”

The storm had started without rain. Out in the reception hall, someone clinked a glass for toasts. Inside the chapel, the organist had started practicing something that sounded like dust. The flowers didn’t wilt; they looked like they were planning it.

Selena’s face went through colors human skin usually avoids. Blue at the mouth. White at the cheekbones. Red in the eyes. “He said he loved me,” she whispered to the floor.

“He did,” I said, because that was true in its way. “He loved a lot of things. He loved big. He loved fast.” I looked at the nurses and then at my parents. “He burned hot.”

“And when he did,” Sophie said, “we were there with water.”

In the days that followed, there were letters. The hospital sent us one printed on paper that felt like a lie—too thick, too clean—thanking us for “conversations that made it possible.” We had not been in those rooms. Tyler had. His lawyer’s letter came in an envelope that knew how to behave. It listed numbers and titles and reminded us of deadlines. It named the fund—The Tyler Okada Patient Compassion Fund—and promised that someone would always explain a bill as many times as needed without using words that make people feel small. It said phrases like restricted gift and endowed and fiscally prudent that made my father’s eyes relax for the first time since the day Tyler’s heart stopped turning the color of blood into something professional.

Selena called me two months later. I was in the grocery store staring at a pyramid of tomatoes that dared me to find one without bruises.

“You have to help me,” she said, skipping hello and sorry and anything shaped like a human entrance.

“I don’t have to,” I said. “But go on.”

“They’re saying I have to take the debts,” she said, breath hitching. “No one told me—no one told me inheritance is… like that.”

“It’s like that,” I said. “Within three months of being informed, you can renounce. If you don’t, you get the house keys and the bills.”

“But the jewelry,” she said, stubborn, childish. “The pieces he gave me.”

“Sell them,” I said. “If you love them more than the man who gave them, they’ll serve you better on a pawn slip.”

She cried then, messy. I looked at the tomatoes and saw nothing but red.

“You cared for what he gave you,” I said when she paused to inhale. “You didn’t care for him. That’s the difference.”

“I did,” she said, reflexively. It sounded weak even to her.

“We postponed the wedding,” I told her. “A year. I can’t walk down an aisle with pictures of him in every room of my head.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, and for a moment it sounded real, like someone in there had pulled the right string.

“Live with the truth,” I said. “It will cost less than pretending.”

I hung up. The tomatoes were all bruised anyway.

In the year that stretched and then finally relented, I learned to move through grief without tripping over it. My fiancé learned to sit with me in silence without trying to sweep. My in-laws brought food and didn’t blink when I didn’t eat. I went to the hospital every Thursday afternoon and sat in a little room with a plaque that held my brother’s name and listened to stories from people who could finally pay for something without choosing between humiliation and chemo. The nurses became my people in the way that family happens after paperwork: slowly, with jokes, with text threads that share photos of toddlers and dogs and overnight doughs that rise under damp tea towels. Miguel sent me a video of a rainstorm from the roof of the parking deck with the caption: Your storm. Different, but here. I saved it.

On our wedding day—exactly a year and a week after the funeral—the sun attempted another performance. It lit the church steps like it didn’t feel redundant. Tyler’s colleagues—fewer this time because hospitals do not run on sentiment—stopped by the grave before the ceremony and set small things on the grass. A donut with sprinkles. A glove. A card that said You were the one who backed up my med math at 3 a.m. when I couldn’t see straight. At the reception, the band played a song my brother used to butcher on guitar when we were kids, and I laughed so hard the cake nearly fell.

People had warned me about “users,” about “hang-ons,” the kind of the-world-owes-me folks who treat kindness like a leak in the roof. They didn’t show up. Maybe the nurses had scared them off with competence. Maybe people can sense when generosity is coming from a place that doesn’t want payment. Maybe there’s a line between generosity and gullibility and Tyler’s fund had drawn it without being a jerk about it. Maybe my brother’s life was a warning and a map and a dare. Maybe. I didn’t need to know.

Someone told me, months later, that Selena had sold the mansion. The jewelry, too. The ring she’d shown off in the hospital corridor was listed on an auction site beside rugs and art and a watch that used to make a tiny chime at the top of every hour. She moved into an apartment with a view of a brick wall and a rent she could afford. The jewelry industry—a world that feeds on stories and stones—made her name into a cautionary tale about lifestyle creep, about living on tomorrow’s hype, about mistaking a gift for a contract. Someone else said she was trying to go back to school. I hoped that part was true.

When I lay in bed at night, I sometimes rewrote the hallway scene. Sometimes I let my hand connect with her cheek. It felt good in those versions. But the one that matters has Miguel’s fingers around my wrist and my father’s voice asking a question and the nurses’ laughter like a window opening. The one that matters ends with a quiet that isn’t silence; it’s a place to sit.

I go to the hospital on Thursdays still. Sometimes I stand outside the fund’s door and listen to voices—care coordinators explaining lines on a bill in simple sentences, a mother saying I didn’t know we could ask for that, a son crying in a way that has nothing to do with money and everything to do with power. I bring donuts on third Fridays. The nurses pretend they don’t know who did it. We all pretend a lot of things to keep going. That’s not the same as lying.

Tyler didn’t leave a fortune for a woman who thought she could spend it better than pain. He left something messier. He left a line in my life between the people who clap for themselves and the people who clap for the work. He left me a fund I don’t have my hands on and a memory I can hold. He left me ten million yen for a dress and a photographer and a hall with sticky floors and a band that covered half the eighties catalogue and stayed for a final set because the drummer liked our friends. He left a party I’ll keep throwing for as long as there are people who need a night where they don’t have to count anything but dances.

On our first anniversary, my husband and I took flowers to the grave. The bouquet was lopsided because that’s how my hands work when I try to make something pretty. We set it down and then didn’t say anything for a while. The sky was exactly as blue as the day we’d lowered Tyler down.

“I’m trying,” I said finally, because it’s a prayer that doesn’t ask for a return receipt.

“I know,” my husband said. He took my hand. We left the churchyard and walked to the hospital. The fund’s door was open. The room was full.

Part II

Two weeks after the funeral, the hospital invited us to a dedication. It wasn’t grand—no velvet ropes, no podium, just a small room near the financial counseling office where the carpet had seen more tears than coffee. A rectangle of frosted glass with my brother’s name etched into it leaned against the wall, waiting for two screws and a steady hand. The head of philanthropy—hair sprayed into a helmet that could hold off weather—shook our hands and thanked us for “conversations” we hadn’t participated in. My father smiled in that way that says, If it helps, let it be yours.

They didn’t unveil a check. They didn’t list an amount. They didn’t need to. The first family to sit under the plaque arrived late, looking dazed. The mother’s hair was still damp like she’d been interrupted mid-shower by a call she’d hoped would not come. The father’s jaw was set in that way men do when they have decided the only thing they can control is their posture. A counselor with a clipboard introduced herself, glanced at us, and said, “Would you prefer another room?” We said no. We stood. We left. We listened in the hallway, not to the details—those belong to no one but the people living them—but to the sound of the counselor’s voice keeping a woman from breaking in half.

That night I dreamed of journals. Not Tyler’s; he didn’t keep any. The leather one from the cabin in that other story people tell about brothers. Pages filled with planting times and weather notes and simple sentences that admit the sky can be kind and cruel in the same afternoon. I woke up before dawn and wrote two words on a sticky note: Keep steady. I stuck it to the bathroom mirror. Some days it looked like advice. Some days a dare.

Selena called the next morning. I was in the office of Tyler’s attorney, a paneled room that smelled like paper and dust and patience. Ms. Kline, a woman in her fifties with a silver streak through her hair and a way of speaking that made calendars behave, had just finished explaining that “insolvent estate” wasn’t a curse, it was a category, and that distribution works different when assets can’t outrun obligations.

My phone buzzed on the desk between us. Ms. Kline moved one finger as if to say take it or don’t; your life is your own. I answered.

“You owe me an explanation,” Selena began, skipping hello and vaulting over how are you like it had been lowered for her at a high jump.

“I don’t,” I said. “But go on.”

“They’re saying I have to decide in three months whether to renounce,” she said, breath hitching. “Three months from when you told me? Or when I found out? Which is it?”

“From when you were informed,” I said. “Ms. Kline can explain in smaller words if that helps.”

Selena bristled. “Don’t be cruel.”

Cruel. I looked around the lawyer’s office, at the law degrees in frames you couldn’t buy at Target, at the pen Ms. Kline had set down between us like a ceasefire line. “You left outline bullets in a hospital hallway about the mansion,” I said. “We’re past the part where insults work. Listen: inheritance includes liabilities. If you accept, the mortgage company meets you before the door does. The car isn’t a gift, it’s a payment plan. The watch is real and so are the taxes. You can sell jewelry; you can’t sell a loan back to the bank because you don’t like the feel of it.”

Ms. Kline cleared her throat in a way that said I’m here. “Ms. Ohata,” she said when I put the phone on speaker, “you have options. A disclaimer within three months is the cleanest. If you miss that, you may be able to petition—but courts don’t smile on people who confuse calendars with feelings. I’m happy to refer you to counsel.”

“I’m not paying for a lawyer,” Selena snapped.

“You’ll pay,” Ms. Kline said, serene as a lake. “One way or another.”

After the call, we went back to nouns and numbers. The will looked nothing like the movies. No violins. No reading aloud to a room of expectant faces. Ms. Kline summarized: a wedding fund for me, the gifts already given, the hospital endowment. Zero to Selena and a paragraph that said the absence was “intentional.” Lawyers never say what they don’t mean. Ms. Kline asked if we had questions; my father raised a hand like he was back in class.

“He bought dinners,” Dad said, not accusatory. “He rented places with views. Did it help?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “Sometimes buying a view is the only way to see past your day.”

He nodded. His eyes looked older than they had at the chapel.

The hospital asked me to say a few words at a staff meeting, fifteen minutes on a Tuesday morning before the surgeons scattered and the nurses changed out at the nurses’ station and the respiratory therapists refilled their carts. I prepared sentences about “impact” and “compassion” and “keeping promises to patients.” When I stood in front of the lunch-and-learn crowd with their branded water bottles and their silence shaped like attention, I said none of it.

“He used to call me on his drive home,” I said. “He would list the facts and then say, ‘I bought a bottle of wine that costs too much, come over,’ and I would say, ‘No, go to bed, drink water.’ He wanted to spend everything—money, time, himself—to make the day not so sharp. I don’t enjoy admitting this part, but I will: I was tired of him sometimes. Tired of his abundance. This fund is what it looks like when abundance goes where it belongs.”

They didn’t clap. They put their hands back on their jobs.

Three weeks in, the gossip column that masqueraded as a lifestyle blog posted a blind item. A certain surgical prince left a certain social butterfly out of his last dance and now she’s spinning a web of woe. The comment section did what comment sections do: divided itself into camps called Pitiful and Predators and Then Why Was She Wearing That Dress. I typed three versions of a paragraph defending Tyler and deleted them all. Ms. Kline liked to say never wrestle with a pig; you both get dirty and the pig likes it. I closed my laptop and baked something from a recipe that demanded attention at unnecessary intervals. When it came out of the oven, the lemon bars tasted like surrender but in a way that could be carried on a paper plate to the nurses’ station.

Selena missed the deadline by a week.

I found out because she called me sobbing from the steps of my parents’ old condo, as if the porch had magic that could deliver her back into grace. “I filed,” she said, “but they said it was late.”

“Courts like clocks,” I said. “They don’t go by hearts.”

“They can make exceptions,” she said, righteous suddenly.

“Sometimes,” I conceded. “Usually not because someone wanted to go shopping instead of read mail.”

Her anger burned hot enough to warp the air. “You hate me,” she said. “You’ve always hated me.”

“I’ve always wished you liked my brother as much as you liked his receipts,” I said. “It’s not the same thing.”

She hung up. It was petty to be grateful for the silence. It was also true.

Collections are a language of their own. They speak in numbers and in insistence and in paper that arrives with red stripes and immediate attention required. Selena didn’t understand the dialect. She started pawn–shop poor, not because those shops are poor—some of them have more money than their clients, just wrapped up in diamonds that used to mean something—but because the rate on a quick loan is not a friend unless you’re trying to escape a fire and it’s your only door. She offloaded the watch. The ring went next, the one she’d shown to anyone who made the mistake of asking about her weekend. The smallest diamonds on the dog-collar necklace brought in less than the boutique had suggested because retail prices float and secondhand sinks.

She called my mother with the kind of voice that rearranges guilt. My mother drove across town with a casserole and three envelopes of cash she had labeled emergency. Selena cried on her shoulder and then on her blouse and left mascara cheap and black and stubborn in the pleats. I was tempted to be angry. Then I remembered Selena had been an orphan before she became a performance piece. You don’t unlearn hunger just because you put on a dress.

“We can’t fix her,” my mother said, wringing out the blouse over the sink with a little laugh to keep from drowning in it. “But I can stand in a kitchen and pretend to be a wall.”

I wrote down resources in a text and sent them without commentary: a legal aid clinic with someone who knew how to talk to creditors; a phone number for a financial counselor at the hospital whose job it was to say let’s see what we can do when people whispered we can’t; a link explaining bankruptcy in gentle sentences that didn’t use the word failure.

She didn’t respond. A week later she did. I’m sorry, she wrote, and for the first time, the syllables didn’t come with a price tag. I didn’t know.

Now you do, I wrote back. Act like it.

In the middle of all of this, a rumor started that the hospital had misused funds—that what Tyler had intended for “people” had been spent on “programming,” a word that sounds wholesome to donors and suspicious to everyone else. A local reporter called me for comment. I asked Ms. Kline; she raised one eyebrow high enough to gather rain.

“Say nothing,” she advised.

I asked Miguel; he said, “Say what helps.”

So I said a sentence into a microphone. “My brother trusted the people who do the work,” I said. “So do I.”

It printed two days later between a yoga studio ad and a story about a dog that had found its way home across three counties. I clipped it and taped it to the fridge next to the county’s thank–you letter. It looked ridiculous. It also looked exactly right.

At the six–month mark, the hospital held a proper event with chairs and a podium and a ribbon the color of dignity. People came. Press intruded gently. A mother told the story of a bill explained, a yard sale avoided, a son who got to keep his trumpet instead of learning what it feels like to trade art for antibiotics. My father cried silently, his face doing nothing except letting water fall. When he hugged me after, his shoulders shook like a boy’s.

After the speeches, a resident in wrinkled slacks and gratitude too big for his chest found me near the coffee urn. “He taught me to tie the knot one–handed,” he said, eyes bright. “He said, ‘You’ll need it when the other hand knows what to do and you just have to catch up.’”

“I believe it,” I said.

“Sometimes I buy a donut on third Fridays and leave it in the OR lounge, even if I’m broke,” he admitted, flushing. “Is that— I mean, does that count?”

“It counts,” I said. “But also—eat the donut.”

We laughed. Someone’s baby shrieked and then calmed. The plaque on the wall didn’t shine any brighter for the attention. It stayed the same. That’s the job of a plaque.

A year felt both too long and exactly right. We got married. We danced to a song that was objectively bad and personally perfect. I didn’t see Selena at the church, but a friend told me she had been hired at a jewelry store across town. Rumor said she had a boss who didn’t allow staff to wear merchandise on lunch. Another rumor said she’d enrolled in a night class. A third said she had moved into a studio apartment above a florist and gone to sleep each night smelling like other people’s celebrations. I hoped that part was true too.

Grief likes to show up when the good things do. On our honeymoon my husband woke to find me sitting up in bed at four a.m., the kind of awake that makes you ashamed of your own brain. “I know,” he said, and I realized I hadn’t said anything out loud.

“We should visit,” I said. “The fund. The nurses.”

“You like to say thank you,” he said, kissing my shoulder. “Let’s go Thursday.”

We did. Sophie told me she had applied to a graduate program and gotten in despite a personal statement that read like a grocery list. Miguel confessed he had started taking night shifts again because “the heart does things at night it won’t admit in daylight.” One of the financial counselors brought a paper chain—the kind kids make in classrooms before the winter break—each link a bill reduced by the fund, names blacked out but numbers legible. She draped it over the back of a chair and said, “When it touches the floor, we’re taking a photo.”

“That’s tacky,” I said.

“That’s the point,” she said.

My father started volunteering once a week, sitting at the information desk with an ancient clip–on tie and the patience of a man who had been an accountant long enough to know where the lost forms hide. People brought him questions he couldn’t answer and he answered them anyway with directions to someone who could. My mother baked. Of course she did. Banana bread mostly. She left loaves with notes that said for whoever needs a slice and didn’t sign them in case the person who needed it was shy.

In year two, the hospital’s newsletter ran a feature on “Donor Stories,” and slipped Tyler’s name into a paragraph that pretended to be about “corporate partnerships.” I wrote an email nicer than I felt, asking them to either use his name properly or not at all. They apologized with a basket and a page two correction. It still counts.

Selena texted once in the fall. I saw his picture in the paper, she wrote. I bought the paper so I could cut it out.

That’s fine, I wrote back. Use good scissors. Don’t tear.

She sent a photo an hour later: the clipping taped above a kitchen counter with a chipped laminate edge. Two mugs hung from hooks. A kettle sat on the burner like someone intended to use it. In the picture’s corner, the edge of a textbook glowed blue. Payroll Accounting. I stared at the title until the letters blurred into shapes. I wrote back: Good choice.

She didn’t reply. She didn’t need to.

At Christmas, my husband and I went to the cemetery with mittens and a shovel because the ground freezes in a way that makes flowers pointless. We brushed snow off the stone and stood there looking at our own breath as if we could read something in it. I wanted to tell Tyler about the fund’s latest story, a family who kept their apartment because a woman with a clipboard had pulled a number from a file and said, “We can make this part go away.” I wanted to tell him that gifts get smarter when you let the people who are already doing the work decide where to put them. I wanted to tell him that his capacity for spending had been a rehearsal for generosity disguised as dopamine.

Mostly, I wanted to tell him I am trying to keep the part of him that wasn’t for show. I am trying to defend legacy without becoming a bouncer. I am trying to accept gratitude without keeping score.

On the way back to the car, I stopped and pressed my ear to the cold air. People like to say “money can’t buy happiness” in that smug way that means the speaker has had their share. It can buy relief. It can buy time. It can buy a Thursday afternoon without fear. That’s not happiness. It’s a floor strong enough to dance on. I’ll take it.

The night before New Year’s, a final card came, addressed in a messy hand I didn’t recognize. Inside, a note: He bought me dinner once when I thought I couldn’t do another nurse manager meeting. He told me a story about a knot you tie one–handed. I’ve used it every week since. I’m writing this because you should know the knot holds. —M.

Miguel refuses to admit he wrote it. That’s fine. I like my stories unsigned.

Part III

The summer the rain refused to stop, the river forgot where its banks were. It crept over sidewalks and into basements, swallowed a parking lot we’d always thought was high ground, and sneaked up the back stairs of the hospital like a burglar who knew the codes. The meteorologist said “one hundred–year flood” in the tone they save for trivia that ruins weekends. We stacked sandbags until our lower backs sent messages to our better judgment and then kept stacking.

By noon on the second day, the emergency room looked like a bus station during a snowstorm: bodies everywhere, bags of clothing, a dog or two that had convinced their humans they were service animals, the smell of wet wool and old fear. The hospital had a plan for this. They’d practiced. Plans are good until weather laughs.

I emailed my boss and got back a one–line reply—Go, we’ll cover—and drove to Graceview with the trunk full of bottled water and protein bars like I was a suburban relief convoy. The cafeteria had given up on menu boards and was ladling hot things into paper bowls for anyone with a wristband and anyone without one who looked like they’d forgotten how to swallow.

Miguel had pulled a double and then somehow pulled another. He met me by the vending machines with a smile that had stopped asking permission to exist. “You look like logistics,” he said, taking the water from my arms before I pretended it wasn’t heavy.

“I brought snacks,” I said. “And a willingness to stand where you point me.”

He pointed. “Family room. The fund’s counselor is triaging people who need hotel vouchers and dry clothes and a lecture about carbon monoxide.”

“Paper chain?” I asked, meaning the garland of bills reduced, the thing we’d promised ourselves we’d photograph when it grew long enough to be embarrassing.

“Broke it last night to make signs,” he said. “We’ll celebrate later.”

The family room smelled like crayons and panic. The counselor—Paula, small, efficient, hair in a bun that looked built for speed—had turned the Tyler Okada Compassion Fund office into a kind of triage desk for everything money could fix fast. People lined up with forms that were already damp before the rain touched them. A volunteer handed out socks and a speech about how dry feet are not a luxury. A maintenance guy pushed a squeegee down the hall in that resigned way that says he has dedicated his life to redirecting water and periodically fails.

“We’re using the fund to book hotels,” Paula said, sliding a stack of receipts into a shoebox someone had labeled tonight. “Shelters are full. Folks need a door that locks, a working shower, and a place to cry without someone’s toddler watching.”

“What do you need?” I asked.

“A person who can do quick math under stress and doesn’t cry when someone yells,” she said.

“I can do the first part,” I said. “I’ll work on the second.”

People came. People told small stories that contained large ones: I can’t find my cat. I’ve been nursing my husband at home and the power went out. My mother thinks she’s in 1982 when the lights go off, and 1982 was a bad year. We booked rooms. We printed maps. We taught three different grandfathers how to scan a QR code by telling them it was like taking a picture of a menu that was too shy to show you its face.

Just before dark, I recognized a voice at the back of the line. It had an edge that used to be my trigger. It sounded different, like it had been filed down by weather. I looked up.

Selena stood there holding a plastic grocery bag that was attempting to be a purse. She wore a raincoat that had not been bought for photographs. Her hair was pulled back with a drugstore clip, and the only jewelry on her fingers was a ring that turned her skin green. She saw me seeing her and something like relief and dread fought each other across her face.

“I’m not cutting,” she said, preemptively defensive. “I’ve been in line forty minutes like everybody else.”

“You want a room?” I asked, because if we were going to do this, we weren’t going to do it via subtext.

She swallowed. “My building’s boiler is underwater,” she said. “The landlord says the hot water will be back when the river remembers how to mind its business. I’m not asking for— I just— I have class in the morning.” She lifted the grocery bag a few inches, and a textbook showed blue at the edge—Payroll Accounting, the same one from the photo she’d sent months ago. It wasn’t a prop. It had been in the rain.

“Name?” Paula asked, pen ready.

“Selena Ohata,” she said, and the sound of her own last name seemed to hit her, the syllables landing like a bird that had finally decided to stop flying in circles.

Paula wrote, nodded, turned to me. “Two nights?” she asked.

“Do three,” I said. “We can always cut it if the boiler behaves.”

Paula’s pen moved like a blade that knew where to cut. “ID?” she asked.

Selena fished in her bag and produced a wallet that had been nice once and now was simply honest. Paula photocopied, stapled, slid a form for signature across the desk.

Selena looked at me. “Thank you,” she said, no performance. The words were thin, but they stood.

“Dry socks,” I said, handing her a pair from the pile. “You’ll think me sentimental, but you’ll cry when you put them on.”

She laughed, a startled sound. “Who are you?”

“Someone who has learned about socks.”

She moved toward the door. Then she turned. “Do you—” She paused. “Do you need help? I can… add numbers.” She lifted the book again like proof.

We did. We needed someone to add numbers and not make them about themselves. For three hours, Selena sat at the end of the table and checked that rooms matched rates, that names matched IDs, that the addresses on the forms weren’t something a person had invented because they were tired and thought a lie would make a door open faster. When the printer jammed, she didn’t kick it. When a man raised his voice, she didn’t cry. When Paula asked for someone to run down to the lobby and pick up a delivery of towels, she went without announcing that she had gone.

At ten, the rain took a breath. The river decided to flirt instead of commit. We packed receipts into the shoebox and cords into a drawer and bodies into elevators. Paula, who by then had eaten two granola bars and twelve sunflower seeds, sat down on the carpet and leaned her head against the desk.

“Tomorrow again,” she said. “Bring coffee. Don’t bring muffins. I hate muffins.”

“Noted,” I said.

Selena slid her textbook into the bag. She looked at me like she wanted to say something big and had decided to go small instead. “I didn’t know what he did would matter like this,” she said, meaning Tyler, meaning money that isn’t yours.

“That’s the trick,” I said. “It matters most when you do it right and least when you try to prove it does.”

She nodded. “Tell your mom I’m sorry about her blouse,” she said, random and true.

“I think she forgave you about four casseroles ago,” I said.

On the way out, we passed a bulletin board with a flyer half–torn: VOLUNTEERS NEEDED — SANDBAGGING AT RIVERFRONT. Selena paused, took a photo. “I’ll go,” she said without checking if I approved.

“Wear gloves,” I said.

“I have two pairs,” she said, and for a moment I remembered the woman in the hospital hallway and the way she had said mansion like it was a birthright. This was not that woman. This was someone who had finally figured out how to hold weight without breaking her nails.

The storm pulled back after three days like a person who had made its point and wanted to be thanked for not making it harder. The water receded, but not gracefully. We found mud in places it had no business being and learned that basements keep secrets you only find when they smell. The hospital bleached everything. The counselors slept and then came back and then slept and then came back again because relief is a rotating door, not a finish line.

The fund’s shoebox turned into a folder turned into a file cabinet turned into a spreadsheet we argued about until we agreed we hated it equally. The numbers were stupid and beautiful. When the chief financial officer asked for “reconciliation,” Paula sent a one–line email—we reconciled humans; the numbers match as well as they need to—and copied Ms. Kline for sport. Ms. Kline replied with a link to a policy that both protected us and made us cuss. That’s governance.

A week after the river climbed back into its pajamas, the hospital held a town–hall meeting. Rumors had begun their own flood—whispers that “the donor family” had influenced who got help, that the fund had paid for “frivolities” like hotel rooms near the hospital for nurses who couldn’t drive home. The comments on the neighborhood Facebook page had gone from thank–you hearts to sentences that smelled like envy. Transparency is a word nonprofits use when they mean we’ll show you enough to keep you from writing letters to the editor.

We gathered in the auditorium. The CFO walked through bar charts that looked like Tetris. The head of philanthropy spoke in nouns you could count. Paula took the mic and did a thing you can’t put in a PowerPoint.

“We booked rooms,” she said. “We bought gas cards. We paid one overdue electric bill because otherwise the NICU nurse who hasn’t slept in thirty hours would have had to go home to a dark apartment after holding other people’s babies alive. If you want me to apologize for that, you’ll wait a long time.”

The room exhaled. It wasn’t applause. It was permission.

Someone in the fifth row stood. It was Selena. She had a bandage on her palm and river mud still in the tread of her sneakers. “The hotel rooms kept me from choosing between a midterm and a migraine,” she said. “I am not special. I was a person who needed a shower and a door that locked. We didn’t game anything. We stood in line.”

The CFO blinked as if he’d never factored stood in line into a model. He wrote it down anyway.

After the meeting, the blog that had written about “the social butterfly” posted an update: Sometimes a door that locks is the only extravagance a person needs. The comments did their division and their petty and their ok but still. The hospital didn’t respond. The work did.

At the end of that month, my mother found a box in my parents’ storage room labeled WEDDING. Inside were napkins with a date we’d postponed and a cake topper that looked like a joke people make at showers when they’re trying to be clever and a sealed envelope with my name in Tyler’s handwriting.

We sat at the kitchen table. The dog put his head on my knee and exhaled a smell like river. My father tore the envelope along the edge like he had done this before and respected paper. He slid the letter to me and then looked away like it was a medical procedure I would prefer to do in private.

It wasn’t long. Tyler didn’t do long unless it was dinner. If I’m not there, it said, do the thing anyway. Buy the good wine. Invite the person who always cries when the band plays “September.” Make Dad dance. Tell Mom to sit down. And if you ever worry that the money was stupid—remember: you can’t take it with you, but you can send it ahead.

He had underlined that part. Twice. It was smug and perfect and made my chest hurt. I folded the letter and put it back in the envelope because I am sentimental and hate repetition.

The hospital sent a thank–you note to the volunteers who had sandbagged. It used clip art and too many exclamation points and a font that belongs on bake sale flyers. It made me grin. Selena posted a photo of her bandaged hand with the caption learned how to lift without my back and then, below that, a quote from an accountant in her class that read like scripture—Assets equal liabilities plus equity—and someone in the comments wrote amen in all caps and then lol and then left it alone.

I walked to the bridge that afternoon—the one we didn’t bounce. The creek had climbed up its sides and then backed down, leaving a line of sticks and a smell like newness. The bench at the overlook had held under rain heavier than any we remembered. The burned letters in the backrest—STILL–HERE SEAT—looked smug. A good bench should.

I sat. The dog leaned against my leg and sighed like elderly men do when they lower themselves into recliners. Below me, a boy in a too–large life jacket splashed like someone who has never not trusted water. A woman in a blue raincoat and a drugstore hair clip walked the path in careful steps and then sped up, because careful is a habit you can unlearn if you try. At the hospital, the fund bought a bus pass and a night’s sleep and six pairs of socks and the right to stop explaining long enough to breathe. That’s not all of it. It’s enough.

I texted Miguel a photo of the creek and wrote: Your storm. Different, but here. He sent back a picture of a donut in the OR lounge. Sprinkles. The caption: Third Friday. Some traditions survive weather.

I went home and started a pot of soup. I used the good broth. I put in too much garlic. I set three bowls on the counter—mine, my husband’s, and the empty one we always set now, without saying why. It wasn’t a shrine. It was a place to keep the part of him that had finally learned to go where it was needed.

Part IV

The letter from the court came in an envelope that had learned how to be heavy. ESTATE: CLOSED. No violins this time either, just a stamped page and a line that said insolvent, distributed per statute. Ms. Kline sent a copy with a sticky note in her tidy hand: We did it right. I slid the letter into the same drawer as Tyler’s, the county’s thank-you, and the clipping about third Fridays. There is a strange kind of peace in the administrative finality of grief. It gives you permission to get on with the parts that don’t care about stamps.

The hospital’s fund did what good ideas do when you stop worrying about how they look—it crept everywhere. The compassion office moved to a larger room with a window that pretended to be a view, and someone had finally replaced the carpet that had seen more tears than coffee. The paper chain—rebuilt after the flood—touched the floor and kept going until Paula insisted we drape it once around the door frame “for architectural interest” and the CFO insisted we count again “for audit integrity.” We did both. Governance can be playful if you let it.

Five years is enough time for a rumor to become a routine. The third-Friday donuts stopped being “a mysterious kindness” and turned into “who’s doing it this month?” Miguel learned to sleep on a couch that hated him and to tie the one-handed knot without looking, then taught it to a resident with hair that defied hospital caps. The resident cried in an elevator and then laughed about it the next day in a voice that didn’t apologize. Sophie finished her program and returned to the ward with new initials and the same walk. Paula kept vouchers in a shoebox and an eye on every policy update like it was a dog she’d agreed to sit for but didn’t entirely trust.

On our fifth anniversary, my husband took me to a restaurant that wanted us to whisper and then to a dive bar that wanted us to shout. Somewhere between the two, I said, “I still bring the empty bowl,” and he said, “We know,” and we left the conversation there because sometimes marriage is agreeing to stop explaining a thing you both understand.

Selena showed up at the hospital on a Tuesday afternoon with a manila envelope under her arm and a haircut that didn’t ask permission. She had the briskness of someone who now walks with purpose because her shoes have learned her routes.

“Got a minute?” she asked, peeking into the compassion office. Paula looked up from a stack of forms and said, “Always,” in the tone of a woman who recognizes paperwork in others the way dogs recognize squirrels.

Selena sat and took a breath and took another. “I finished,” she said, and slid a certificate across the desk like it might land wrong if she pushed too hard. Accounting Principles—Certificate of Achievement, stamped, signed, real. “I passed the payroll exam last week.”

“Congratulations,” I said, because easy words need to be said out loud.

She nodded once, brisk, then reached back into the envelope. “I also brought this.” A single sheet of paper, a statement with a zero. ACCOUNT: PAID IN FULL. It had taken five years of nights and noodles and saying no to things that didn’t come with receipts. She had kept the apartment above the florist. She had kept the mug hooks. She had converted the bruised blue textbook into a credential and the credential into a job: billing clerk at a clinic that treated the uninsured on Tuesdays and Thursday nights. She had learned how to tell people they owed money without making them feel like thieves.

“Sometimes I tell them about the fund,” she said, looking at the carpet like the story lived there. “I say, ‘There are people who know this hurts. Let’s call.’”

“You don’t have to—” I started.

“I know,” she said, a little smile. “I want to.”

She pulled out one more thing—a check, modest, folded. “This is… not much. It’s one hotel room, or half of one if it’s near the hospital. It doesn’t have a name attached. I don’t want a plaque. I don’t want a ribbon. I don’t deserve either. But I want to spend a little, the right way.”

Paula took it with two fingers like it was fragile and holy. “We’ll put it where the day needs it,” she said. “That’s what money wishes it could do.”

Selena stood. She looked older and better for it. “I’m going to tell your mom I’m sorry. To her face,” she said. “Not because I want anything. Because I owe it.”

“She’ll feed you,” I warned.

“I’m counting on it,” she said, and left with a wave that did not beg to be seen.

The hospital dedicated the new family resource room the next spring. It had taken three capital campaigns to get the holes out of the roof and the ghosts out of the budget, but someone with good taste and bad funding had found a way to make the space both pretty and stubborn. There were lamps that made the light warm and chairs that made backs forgive. There were computers whose home screens explained where to click without making you feel dumb. There was a closet with puzzles and socks and two strollers whose wheels actually worked.

The head of philanthropy wanted to call it The Okada Center and hang a portrait. I said no. I said yes instead to a little brass plate by the door with six words: KEEP STEADY — TYLER OKADA — THURSDAYS. People will ask, I knew. Paula will tell them if they need to know. The rest of the time, it can be something people pass and don’t register except in a muscle they can’t name. We cut the ribbon without a ribbon because I argued we should spend the ribbon money on three bus passes, and the head of philanthropy said, “You’re impossible,” and then bought bus passes out of her own pocket because she’s not the villain in this story.

I gave a speech that wasn’t a speech. “We’re not cutting a ribbon,” I said. “We’re opening a door.” The crowd did a little noise that wasn’t applause and wasn’t cough. It was relief. We walked through together. Sometimes the right ending for a sentence is the door it opens.

The fund kept being a floor, not a ceiling. We paid a thousand little bills and said a thousand little no’s and a hundred quiet yes-es that never made newsletters and never will. People brought stories into the room with the socks and the computers and left some of them there. We learned to accept the ones we could carry and set down the ones we couldn’t without making the person who told them feel like they had become too heavy.

Miguel sent an email the week after the dedication. Subject line: Knot. Body: a photo of a hand—older now, still his—tying the loop one-handed over a tube. Caption: Still holds. I printed it and taped it inside the closet door where the socks live. Some truths don’t belong in frames; they belong in places you find by accident.

Selena came to dinner on a Tuesday, at my mother’s request. She brought her own fork because she’d been raised by people who taught her to assume nothing. My mother cried and then laughed and then fed her until she was a person again instead of a guest. Selena said, “I’m sorry,” messy and full and without a pitch. My mother said, “You were hungry,” and “you are not now,” and “here, take this,” and slid Tupperware across the table like a sacrament.

After dessert—banana bread because my mother does not know how to be anyone else—Selena reached into her bag and pulled out a little velvet thing with the polite stiffness of stores. She opened it. A ring sat inside, not the ring, but a ring—a small stone, a modest band, bought back from a pawn shop for less than the shop had given her five years ago.

“I don’t wear it,” she said. “I keep it in the medicine cabinet. It reminds me that beautiful things are only beautiful if your life can hold them. I thought maybe—” She stopped. “I thought maybe you should hold it for a while.”

I could have said no. I could have given a speech about letting go. Instead, I took the ring and set it on the shelf above my kitchen sink next to the card with Keep steady and a photograph of the bench at the overlook that someone else had taken when the light was kinder than usual.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll hold it. Together.”

She smiled and rolled her eyes at herself like someone who has become allergic to melodrama. “I’ll pick it up in six months,” she said. “Remind me if I forget.”

“I will,” I promised. The ring looked smaller on our shelf. It was a relief.

Five years is long enough for the numbers to turn into people in your head when you fall asleep. It is also long enough for people to turn into numbers when you are tired and need to make a decision that matters more than your feelings. The gift is knowing the difference from the sound they make when they land.

On the fifth third Friday—say it fast and you’ll either grin or curse—we brought donuts and bagels because Miguel had finally admitted some mornings ask for yeast and others for chew. The OR lounge filled with sugar and that flattening fluorescent light that makes even joy look clinical. I left the box and a note that said nothing sentimental because someone would take a photo for Instagram and I refuse to be anyone’s content.

In the afternoon, an elderly couple sat under Tyler’s plate while Paula explained deductible without using obligation. The woman wore lipstick like armor and shoes that didn’t forgive. The man wore a tie that had belonged to someone else first. When Paula finished, the woman said, “So you’re telling me we can pay eighty now and breathe?” and Paula said, “Yes,” and the woman set down her purse and cried like that amount had been a lever holding the rest of the day up. We booked them a ride home in a car that smelled like pine trees and bad math. They held hands in the backseat like teenagers.

I walked outside and stood under the awning and watched a thunderhead pretend and then decide against it. The air felt like a hallway where someone had opened two doors opposite each other. The river minded its business. The hospital did the same. My phone buzzed. A photo from Jules: the boys—no longer boys—standing in their own shop in the old diner space. A new sign over the door: BridgeWorks. A caption: Hank says we almost know what we’re doing. I sent a heart and then a text to Miguel: Your third Friday? He sent back a photo of sprinkles in a plastic bowl and the caption: We innovate.

On the way home I detoured, as I always do when I have a hard day or an easy one, to the trail. Biscuit is older now and therefore, by his own logic, entitled to amble. We crossed the Not-So-Boring Bridge; it still didn’t bounce. The creek laughed anyway. At the overlook, the STILL–HERE SEAT bore a notch we didn’t carve, the kind of scar that means I have lived. Someone had left a pair of kids’ sunglasses with pink frames on the bench back. We didn’t move them. The right people always come back for what they can’t live without.

I sat. Biscuit leaned. The forest did whatever math forests do. I thought about the parts of my brother I will never keep and the parts I owe strangers now—the Thursday afternoons, the donut without a name, the seat that holds weight without asking why.

When we got home, the kitchen smelled like soup because soup is the appropriate ending to most days. I set three bowls on the counter, because habits matter—mine, my husband’s, and the empty one for whatever we owe the hour. I took the ring down from the shelf, held it up to the light, and then set it back where it belonged among the Post-it, the photo, the basil plant I keep forgetting to water.

I do not know what grief becomes next. I know what I owe it: to stay soft exactly where it would be easier to calcify. To guard Tyler’s name without turning it into armor. To keep Thursdays. To keep steady.

Later that evening, a message arrived from a number I didn’t recognize. We just got home from the hospital. Someone explained the bill like we were humans. There was a sign on the door with your brother’s name. I don’t know him. Thank you anyway. It wasn’t signed. It didn’t need to be. I typed two words back, a sentence that used to feel like bragging and now feels like the smallest kind of truth.

We’re here.

The dog snored. The soup cooled. Outside, the wind moved the pines precisely enough to be seen. I turned off the kitchen light and left the porch light on because this is a house that expects company, even when it doesn’t.

Some nights I take out Tyler’s letter and run my finger under that underlined sentence like a child sounding out difficult hymns. You can’t take it with you, but you can send it ahead. What a tidy, arrogant thing to say. What a decent way to live.

The doorbell will ring again. The river will flirt with its banks. The paper chain will need taping. The third Friday will arrive. The bench will hold. The bridge won’t bounce. And when all of it feels both too much and barely enough, I will do the thing in the letter.

I will keep the door open.

The End

News

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

Sister Announced She Was Pregnant With My Husband’s Baby at My Birthday—She Didn’t Know About the Prenup CH2

Part I The florist had crammed the hotel ballroom with white roses because “thirty deserves a thousand blooms,” according to…

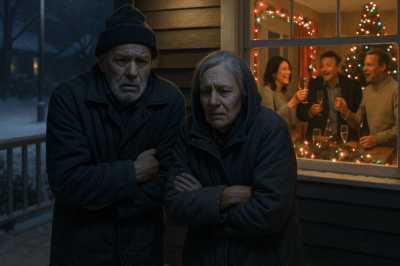

I Found My Parents Locked Out With Blue Lips While My In-Laws Partied Inside…So I Made Them Pay CH2

Part I — When Help Knocks and the Locks Change Robert said it like he was reporting the weather. “My…

Parents Chose a Vegas Poker Party Over My Surgery — My 3 Kids Left Alone, and I Finally Cut Them Off CH2

Part I: The Line in the Doorframe I told the bank we were done. That was the sentence that cut…

WRONGFULLY JAILED FOR 2 YEARS – NOW I’M FREE, BUT EVERYTHING I BUILT IS GONE CH2

Part One: The Strip-Mall Law Two years of my life were stolen because I was walking home from school. That’s…

Black Nurse Insulted by Doctor, Turns Out She’s the Chief of Surgery CH2

Part One: Night Shift The night shift in the emergency department had a sound all its own—a layered hum of…

End of content

No more pages to load