Part I

When the elevator doors slid shut on Emma’s face, I allowed myself the kind of smile you keep hidden in a pocket: small, private, undesigned for witnesses. She was still standing in the lobby, marble under her heels, surprise still warring with rage in the angles of her mouth. She had wanted me to plead. She had wanted the scene everyone whispers about for years.

Instead, I said, “Goodbye, Emma. I hope you find what you’re looking for,” and pressed the close-door button with a thumb that didn’t tremble.

Phase one was complete.

For the next few weeks, I curated a version of myself with a precision that would have impressed any museum registrar. I moved my things into my brother’s old hunting cabin on the edge of town—though publicly, I told people I’d taken his spare room for a while. The cabin was pine and quiet and smelled like dry leaves and memory. It had a porch that faced a skinny slice of sky and a woodstove that clicked as it cooled at night. In the mornings, birds argued in the pines while I drank coffee from a chipped mug and reminded myself: patience is a tool.

I parked my old backup truck in the gravel—a sun-faded, rust-licked pickup with manual windows and a radio that only found stations if you begged it. I let my beard grow in patchy and unbothered. I wore jeans with honest fray and boots with scuffed toes. I became, in the visible ways, a man who had lost everything and didn’t much care.

People notice even when they pretend not to. In the East High hallways, students whispered as they passed. Mr. Reed’s got a beard now. Mr. Reed looks tired. I shrugged and talked Reconstruction and the Harlem Renaissance and the way history never really leaves, it just changes jackets.

At a discount grocery store one Saturday, I was loading paper bags into my truck—eggs, coffee, apples—when a white BMW turned into the lot and paused like a cat considering a bird. Emma. Large sunglasses. Silk scarf. The practiced carelessness of someone trying very hard not to be seen.

Our eyes met. I nodded once, a gesture so small it was almost a flinch. Then I slid into the truck and drove away with the windows down and the radio static pretending to be a song.

That evening, my phone buzzed. Lucas, are you doing okay for money? I can help if you need it. The irony made me laugh out loud in the cabin, the sound bouncing off knotty pine like a stray ball in a small gym. I didn’t reply.

On Monday, the principal called me into her office. Dr. Martinez was the sort of leader who could correct you without shrinking you. She gestured toward the chair opposite her desk. “Close the door, Lucas.”

I did. The office smelled like dry erase markers and peppermint tea.

“I’ve noticed some changes,” she said. “And so have other people. If you’re going through personal difficulties, the school can offer resources—counseling, flexible time, whatever you need.”

“Emma and I are getting divorced,” I said. The truth wasn’t heavy on my tongue. “It’s amicable.” A lie small enough to pass undetected. “I’ve moved out while things get settled.”

She nodded, her expression sympathetic but never pitying. It’s a talent, that line she walked. “Understood. Just know your work hasn’t suffered. In fact, if anything, you’ve been—” she thought for a second “—even more engaged. Your students feel it.”

There was a sort of relief in the classroom now that my evenings were no longer spent bracing for Emma’s comparisons to people who lived their lives in filtered squares and choreographed stories. In the classroom, I could be wholly present. I could be the person I liked being.

“Teaching’s been my anchor,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “The school community is here for you. Don’t forget that.”

I thanked her and walked back into the hallway with that strange mixture of guilt and gratitude I’d been hauling around lately. The divorce was real. So was the devastation it left in its wake. But the rest—the truck, the cabin, the tiredness I wore like a sweater—was theater. Necessary, and not entirely comfortable.

Because behind the scenes, a machine older than Emma and more patient than love was finally ready to run.

Two days after we signed, my phone rang with a number I knew as well as my own name. “Mr. Hines,” I said.

“It’s time, Mr. Morgan,” he replied, precision in every syllable. “The waiting period has elapsed. The divorce will be final soon. Your grandfather’s instructions can now be followed.”

I drove to the old private bank where Morgans had been greeted by name since before the Depression. Marble floors that clicked under shoes. Dark wood that drank the light. A vault that looked like a movie set and was more dangerous than one.

He was waiting in a private conference room with a leather portfolio the color of good coffee. “Lucas,” he said, standing. “You look very much like your grandfather.”

“People always said that,” I answered, shaking his hand. “I never heard it until lately.”

“Discretion,” he said as he sat, opening the portfolio, “has always been the Morgan way. Your grandfather was specific about the terms of his estate. He wanted to ensure the family legacy was protected. And the name change…”

“Was his idea,” I finished. “A precautionary measure.”

“Exactly.” He slid papers across the table. “Reverting to your mother’s maiden name was a way to protect assets until they could be secured. You executed that change two years ago. It proved wise.”

I thought of the afternoon five years earlier when I’d sat in my grandfather’s study, the rain tapping the lakehouse windows, and told him I was worried. I had been married a year and already felt the tremors—Emma’s restlessness, her hunger that felt like a moving target, her jaw tight with envy at other people’s vacations and countertops. He’d listened, eyes on the water. Then he’d suggested the name. Not a lie. A restoration.

“The trust is substantial,” Mr. Hines said, businesslike, the word “substantial” doing more work than it appeared. “Properties across the Northeast. Significant stock holdings. The foundation, of course. Your grandfather continued to invest wisely until his final days.”

The numbers on the page didn’t look real, which is something rich people say when they’re trying to appear humble, but in this case, it was true. Eight figures. The kind of sum that could undo a city if you weren’t careful. The kind that could build one if you were.

“And the condition?” I asked, though we both knew the answer.

“Met,” he said. “The trust activates fully after the divorce is final. Mrs. Reed has no legal claim to anything bearing the Morgan name.” He slid a small envelope across the table. “He left this for you.”

The handwriting on the front was the steady script I’d seen on Christmas cards since I was six. Inside: a key, heavy and old; a note short enough to memorize.

Lucas, if you’re reading this, you’ve shown the patience and foresight that a Morgan requires. The key opens the lakehouse study. What you find there is your true inheritance. Use it wisely. With pride—Grandfather.

I folded the paper, the way he had taught me to fold good paper, and put it back in the envelope. “What happens now?”

“Now you decide how to proceed,” Mr. Hines said. “The foundation requires attention. Board meetings, investment decisions. Nothing urgent. Your grandfather ensured a smooth transition. One matter, however—” he slid a heavy card toward me “—the annual gala. Next month. Your presence is expected.”

I looked down at the invitation and had to bite back a laugh. The Morgan Cultural Heritage Foundation Black-Tie Gala. Politicians, business leaders, socialites. The exact sort of evening Emma would have curated on her dream boards. “I’ll be there,” I said. “But until then—”

“Confidential,” he said, nodding. “Of course. There may be some press. Business journals. Local news.”

“That’s fine,” I said. “By then, it won’t matter.”

On the drive north, the sky unclenched and widened into copper. The lakehouse rose out of the trees the way all childhood places do—smaller and somehow bigger than you remembered. Cedar and stone, the porch facing water, the air that particular mixed scent of pine and old books. I walked through rooms I could have navigated blind—the living room with its mammoth fireplace; the kitchen where my grandmother taught me to crimp a pie edge with my thumb; the sunroom where my grandfather and I had played chess and he had let me win only twice.

Then the study. The key turned like a story finding its ending. The room was as it had been: shelves to the ceiling, the oak desk, the window framing the lake like a painting that moved.

I opened drawers. Photographs. Journals with his looping hand that somehow looked like mine. A tray with watches—leather bands worn smooth, metal faces that had counted hours of decisions I hadn’t been alive to see.

My phone buzzed and kept buzzing. I ignored it until curiosity won. Unknown numbers. A text from an old friend: Dude. Is this you? A link from Mr. Hines.

Mysterious Millionaire Philanthropist Lucas Morgan, the New Face of Cultural Heritage.

The article was thorough in the way only local press can be when they’ve been waiting for a story for years. The Morgan family’s history. Their contributions. The foundation’s role in the city. A mention—dry as a martini—that I would be taking the helm. A photo from my grandfather’s funeral: me at twenty-eight, clean-shaven, a suit that fit like inheritance, grief making me look temporarily older. No one who knew me as Lucas Reed would put that image with the man with a beard in worn jeans who taught juniors about Jim Crow laws and built side tables for fun.

The phone rang again. I didn’t need to check the caller ID to know.

“Hello, Emma.”

Breathing. A small hitch, then the voice I had heard in the kitchen, in the car, from the other pillow. “Lucas, is this… is this really you?”

“It is.”

“This article about Lucas Morgan. That’s you.”

“Yes.”

She made a sound that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be a laugh or a sob. “But you’re— you’re Lucas Reed. A history teacher. You make furniture in your garage.”

“I was Lucas Reed. I changed my name back to Morgan after my grandfather died. I still teach history. I still make furniture. I also happen to be the heir to the Morgan estate.”

Silence that stretched long enough to read a paragraph and a half. “Why didn’t you tell me?” she whispered.

“Tell you what? That my grandfather had money? That my last name used to be Morgan?”

“That you were—” she groped for the right insult and the right compliment “—this. All these years, you let me believe—”

“That you married a simple teacher with no prospects?” I said. “That’s exactly who I was. The money was his, not mine.”

“You must have known you would inherit.”

“I knew there was a trust,” I said, choosing the version of the truth that was less complicated. “I didn’t know the details until recently.” Which had the advantage of being a half-lie that didn’t make me feel dirty. “Not that it would have mattered to you, right? You didn’t leave because I was poor. You left because I was ordinary.”

Another silence. Then: “Can we meet?” Her voice steadier, the actor finding her mark. “To talk. There’s so much I need to say.”

I should have said no. Curiosity is a sloppy lawyer. “Fine. Main Street coffee shop. Tomorrow. Noon.”

“Thank you, Lucas. I—”

I hung up before she could finish the sentence with something that would make me angry or sad.

On the desk, beneath the journals, a manila folder with label-maker precision: Emma Reed — Background.

I sat very still. Then I opened it.

She grew up in a suburb I knew well—split-level houses and chain-link fences and a neighborhood pool that closed every August for a mysterious “chlorine shock” that we all knew was a euphemism for a Saturday night party gone too far. Nursing degree abandoned after the wedding. The Instagram ghost that began to possess her two years later. The affair with Caleb Stewart, documented in photographs that made me feel simultaneously vindicated and unwell.

I closed the folder and stared at the wall until the books looked like a city from a distance.

There is no triumph in being right about betrayal. There is only the dull ache of a wound you can’t tell anyone about without sounding smug or pathetic.

The coffee shop was busy the way small-town coffee shops are at noon—strollers bumping chairs, laptops claiming outlets, the smell of espresso and cinnamon dominating the air. I chose it for its publicness. A place where no one would cry loudly.

She was already there at a table by the window. New dress. New earrings. New face, somehow, though the bones were the same. She stood halfway and then sank back down like the floor had tilted.

“Lucas,” she said.

“Emma,” I answered, sitting across from her. Two mugs were already on the table, steam curling. “You remembered.”

“Black with one sugar,” she said, as if reciting a line. “Some things you don’t forget after eight years.”

We looked at each other over the rims of cups like we were going to be graded on it. She was nervous—her fingers tapped the ceramic, her eyes flicked between me and the window where two teenagers were taking a selfie.

“You look good,” she offered.

“Thank you,” I said. “What did you want to talk about?”

She flinched at the precision of the question. “I wanted to apologize for how things ended. For what I said about you. About us.”

“Apology accepted,” I said. “Is that all?”

She blinked. “Lucas, please. I made a terrible mistake. I didn’t know—” she gestured vaguely toward the ceiling and, by extension, the newspaper and the foundations of the city “—all this.”

“That’s your mistake?” I asked. “Not the lying. Not the hotel with Caleb. Not the years of making me feel like I was a consolation prize. Your mistake is not realizing there was money.”

Her face went white in the way that looks like stage makeup. “You knew about Caleb?”

“I suspected. Now I know.”

“It wasn’t serious,” she said quickly, the way someone backpedals on ice. “He made me feel—special. Wanted. And I didn’t—” she swallowed “—I didn’t feel that way with you anymore.”

“Because I loved my job. Because I built furniture in the garage. Because our countertops weren’t marble,” I said. “Say it plain.”

She sucked in a breath, then let it out. “Because you were content. And I wanted more.”

“And now?”

“And now I realize what I threw away,” she said, meeting my eyes with a sudden ferocity that looked a lot like hunger. “Not the money. You. Your steadiness. Your kindness. The way you believed in me even when I didn’t deserve it.”

There was a time when that speech would have opened a door in me so wide the wind would have knocked down lamps. Today, it moved nothing.

“The divorce is final,” I said. “We’ve both moved on.”

“Have we?” she asked, reaching, fingers inching toward my hand like a vine toward sun. I pulled mine back into my lap.

“We can start over,” she said. “You and me. A fresh beginning.”

“What we had,” I said, “was a fantasy. Yours of who you wanted to be. Mine of who I thought you were.”

“I loved you,” she said. “I still—”

“Do you love me,” I asked, not unkindly, “or the idea of being Mrs. Morgan?”

She flinched as if she’d burned herself on the mug. “That’s not fair.”

“Two weeks ago, you couldn’t wait to be rid of me,” I said. “Nothing has changed except a newspaper headline.”

“Everything has changed.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and for once, I meant the words exactly as they are defined. “The answer is no.”

“Is there someone else?” she asked, desperate now, as if jealousy could do what regret could not.

“No,” I said. “This isn’t about anyone else. It’s about us. It’s about trust. You broke something that doesn’t glue.”

“Anything glues,” she said, leaning forward like she might sew us back together with her eyelashes. “If both people try hard enough.”

“I don’t want to try,” I said, and stood. “Goodbye, Emma. I wish you well.”

I left half a cup and the weight of ten years on the table and walked outside into the kind of spring air that makes even old towns smell like first drafts. For the first time in months, the horizon didn’t feel like a wall. It felt like a road.

I drove straight to school and graded essays until my eyes ached. There is grace in the mundane: circling comma splices, writing Good insight here in margins, telling a kid named Andre that his comparison of Frederick Douglass to modern activists made me think new thoughts. By the time the bell rang for last period, I had found the center of myself again.

After the final student wandered out, Dr. Martinez appeared in my doorway. “Got a minute?”

“Always,” I said, setting the red pen down like it might stain the conversation.

“I just got a call from the Morgan Cultural Heritage Foundation,” she said, watching me like a hawk that has no intention of swooping. “They’re offering to fund a new history program—resources, guest speakers, field trips. The works.” She paused. “Funny thing is, they specifically mentioned you as the teacher who would head it.”

“Interesting,” I said, keeping my face as smooth as a sheet of copy paper.

“I don’t know anyone there,” she added, the corners of her mouth twitching.

“Neither do I,” I said.

She smiled, satisfied she’d made her point. “I told them we’d be delighted to accept.”

“The kids will benefit enormously,” I said.

She reached for the doorknob, then stopped. “Whatever’s going on in your life, Lucas,” she said, “I hope it keeps going in the direction it is.”

Three days later, Brett Donovan, Esq., called while I was hand-sanding the edges of a battered writing desk I’d rescued from a closet at the lakehouse. “Mr. Reed,” he said—then, with a pause, “Or should I say Mr. Morgan?”

“Mr. Morgan is fine,” I said, brushing sawdust off my jeans. “What can I do for you?”

“My client, Mrs. Reed, has concerns about potentially hidden assets. She’s considering legal action to reopen the settlement.”

“I disclosed everything held under the name Reed,” I said. “As required.”

“You were aware of your inheritance,” he pressed.

“I was aware of a trust,” I said. “Not details. Not access. Not control. At the time of our divorce, those assets were not mine to disclose. They became mine after—because—there were no outstanding legal connections to a spouse.” I let the words land. “I suggest you read the trust documents from 1948. Mr. Hines has them color-coded.”

Silence. Then an exhale that sounded like capitulation. “Off the record,” he said, “this won’t go anywhere. Your grandfather’s lawyers were… thorough.”

“They’ve had generations of practice,” I said. “Good day, Mr. Donovan.”

Emma texted that night. You lied to me all those years, pretending to be someone you weren’t. I’m going to fight this. You owe me.

I didn’t respond. There are some fights you win by not showing up.

The morning after, I ordered a new tux. Mr. Hines walked me through a seating chart that was half social map, half minefield. We drafted talking points for people who wanted to be reassured and for people who wanted to be charmed. I wrote a speech. Simple. Sincere. I practiced it to the empty lakehouse until the words sounded less like sentences and more like truth.

The day before the gala, I slid my resignation letter across Dr. Martinez’s desk.

She read it, nodded, and then looked up with that look she uses when a kid tries to pretend he didn’t cheat on a test he very much cheated on. “I had a feeling this was coming,” she said. “The Morgan Foundation’s new education director needs more than a prep period to run field trips.”

“You knew,” I said, equal parts alarmed and relieved.

“I’ve been in education thirty years,” she said, laughing. “You’re not the first person to think a principal doesn’t know how to use Google. Your secret’s safe. My only condition is preferential treatment for East High in future grants.”

“Consider it done,” I said, and meant it.

That night, I sat on the dock and watched a storm gather in the west, the lake wearing the sky’s moods like a shawl. The phone buzzed. Mr. Hines: Board approved your education initiative. Congratulations.

I typed: Thank you. Just the beginning.

The water darkened. The first cool drops found my face. In the distance, thunder rolled like an old engine learning how to run again.

Part II

The Rochester Museum of Art wears its history like a well-tailored suit—clean lines, old money in the bones of the place, plaques that whisper the names of families who believed their fortunes should outlive them. By the time I arrived, the crews had finished polishing the marble floors until they caught the light like a lake at noon. Tables dressed in linen ringed a low stage; strings rehearsed a soft something in the corner; the bar stood ready as a diplomat. The air smelled faintly of wax, lilies, and expectations.

Mr. Hines awaited me beneath a bronze of an American bison that had been donated by a Morgan in 1922. He wore a tuxedo that might have been the same one he’d worn to my grandparents’ fiftieth; men like him keep their wardrobes in a state of perpetual correctness.

“Mr. Morgan,” he said, the old-world courtesy never for show. “Everything is prepared. Board members will want a moment with you. A few remember you from your youth.”

I smiled. “I was the child who tugged on sleeves and asked what they did with all the money.”

“They found it refreshing,” he said, which I suspect was lawyer for it was chaos and we all survived. He led me through the galleries, pausing to note the small plaques: Morgan Foundation, acquisition support; Morgan Conservation Fund, restoration grant. The name felt different now—no longer a myth I’d been born adjacent to but a weight I had chosen to carry.

In the main hall, one of the board members—an arts patroness with hair arranged into a geometry that defied weather—extended both hands. “Lucas. Your grandfather adored you. He would be delighted to see you standing here.”

“He taught me how to stand still,” I said. “Then how to move.”

She laughed. “He taught us all that.”

We were three conversations into the evening when I felt it—the way a room changes temperature without the thermostat moving. I glanced toward the entrance and saw the cause: black silk catching chandelier light, blonde hair smoothed into something formal, eyes scanning for mine like a hunter seeking a particular deer.

Emma was not on the list. Of course she wasn’t. She was, however, a woman who could talk her way into anywhere, especially if she used the word wife in two tenses at once.

Our eyes locked. She offered a tentative smile that would have toppled me a year ago. I tipped my head in the subtlest of do nots and turned back to the museum director, who was telling me about a planned exhibit of WPA photographers. After two minutes of failing to ignore the gravitational pull of drama, I excused myself.

She waited near the doorway, posture composed, desperation haunting the corners. “You look… different,” she managed.

“You shouldn’t be here,” I said softly. “This isn’t your night.”

“I needed to see you,” she replied. “You’ve ignored my calls.”

“Because there’s nothing to say,” I said. “Not here. Not now. Not anymore.”

“Just five minutes,” she pleaded, fingers tightening on her clutch. “Five minutes and I’ll leave.”

I didn’t want a scene that would force Mr. Hines to deploy discreet security. I stepped with her into a side corridor where portraits watched from gilt frames. “Say what you came to say.”

“I made the biggest mistake of my life,” she said. “I know that now. I keep trying to go back to the moment at the elevator and stop the doors from closing.” Her eyes flicked to mine, a dare and a prayer. “You once told me forgiveness is a discipline, not a feeling. Can’t you try? Just… try?”

My grandfather had said that. I had repeated it dutifully. The thing we never say is that discipline is spent on something we value. “This isn’t about forgiveness,” I said. “It’s about consequences.”

Her mouth tightened. “So you get to play wounded saint, inherit a fortune, and leave me with scraps after eight years? Where’s the justice?”

“You got what you demanded in the settlement,” I said. “The house. The car. The furniture. You insisted on the terms. You wore triumph like a perfume.”

“I wanted security,” she snapped. “I didn’t want to be poor with a man who refused to try.”

I thought of the cabinet I had built in our garage on summer evenings, the shavings curling like pale commas, Emma staring at a screen that glowed blue on her face. “I did try,” I said. “I just didn’t try at what you thought mattered.”

“And now it turns out the only thing that mattered to you was your secrets,” she fired back. “Your money. Your old family games. You set me up.”

“No,” I said. “I protected what wasn’t yours.”

Her jaw worked. For a moment, we were two people on opposite riverbanks shouting you don’t understand at the water. Mr. Hines’ voice drifted from the hall: “Mr. Morgan—they’re ready.”

I inclined my head. “I have to go.”

“And me?” she asked, panic bleeding into the question.

“You promised five minutes,” I said. “Please leave. You don’t want to be escorted out.”

Anger flared then guttered in her eyes. She looked over my shoulder at a portrait of a woman in a high collar who had survived some century’s worth of disappointments and carried on anyway. “Goodbye, Lucas,” she said. “I hope the money keeps you warm.”

“I hope the truth does the same for you,” I replied, and stepped back into the room where my past and future had decided to meet.

I ascended the small stage and stood behind the podium. The strings quieted; conversations softened to a murmur; forks paused in midair. I looked briefly at the door. Black silk vanished down a corridor. Then I looked at the audience, at the faces that had known my grandfather as a force of nature and me as the boy who knocked over a tray of canapés at age nine and apologized for a week.

“Good evening,” I said. The mic carried it cleanly to the furthest table. “Thank you for being here to honor a legacy that is larger than a name and older than any of us.”

I spoke of my grandfather’s beliefs—how art and history are not ornament but infrastructure for a city’s soul. I promised continuity where it mattered, change where it would make us more honest. I spoke of East High without naming it, of teachers who create miracles out of scarcity, of twenty-five teenagers in a room discovering that Frederick Douglass once walked the streets we do and insisted on a country that keeps its word. I proposed an initiative: embedded historians in public schools; primary-source kits; field trips funded without bake sales. I made an ask that was less than we could afford and more than most would give without being asked well. I kept it brief, the way my grandfather had taught me: “Leave them with appetite, not indigestion.”

The applause surprised me in its warmth. After, hands, hands, so many hands—politicians who smelled faintly of optimism; donors who wanted to recall how they had danced at my grandparents’ anniversary; an artist who pressed a small catalog into my hands and whispered, “Your grandfather bought my first piece and saved my life.”

The rest of the night was the hum of a party that knows it has done the ritual properly. Near midnight, the crowd thinned. I found a quiet pane of glass and looked out at the museum garden—sculptures rising from shadow, hydrangeas ghost-pale. Mr. Hines appeared as if the building had conjured him.

“She won’t trouble you again,” he said, meaning Emma. “Security knows her face.”

“Thank you,” I said. “I doubt she’ll try a second time.”

“She is a woman who reads weather,” he agreed. He clasped his hands behind his back and regarded me in profile the way he might a painting he’d already decided to admire. “You did well.”

“I didn’t trip,” I said. “Grandfather would call that high marks.”

“He would call it exactly right,” Mr. Hines said, and patted my shoulder in the smallest, most Victorian of blessings.

The letter arrived a week later by courier. The envelope was expensive, the kind stationers put under glass, her handwriting still the same composition-class flourish. I considered handing it back unread. I slit it with my grandfather’s letter opener, the one shaped like a heron’s beak.

Lucas,

I won’t bother you again after this. I needed to say things that didn’t come out right when we spoke.

I am sorry—not just for leaving, but for how I treated you while I stayed. You deserved better than my endless comparisons and my appetite for a life we never agreed on. You gave me patience I called passivity and steadiness I called small. I called your kindness a lack of ambition because it wasn’t ambition I could post. I was wrong.

Caleb is gone. Not that it matters now. He left the second your article appeared. His big investments were more story than fact. I suppose we both fell for men who were not who we thought they were.

My mother says I’ve learned my lesson. Perhaps I have. The worst part is the nights. Not because I miss your money—though you won’t believe that—but because I miss the person I was when you thought well of me. I miss your laugh in the kitchen when you burned the pancakes and refused to throw them out “on principle.” I miss the way you looked when a student surprised you with a thought you hadn’t had yet. I miss the you I couldn’t see because I kept looking at the horizon.

I hope you find a woman who loves the man you are. I wish it could still be me. It can’t. I know that now.

With regret,

Emma

I placed the letter in the bottom drawer of my grandfather’s desk, next to the folder labeled with her name. A story needs a spine and a back cover. This was both.

That afternoon, I drove into the city and parked in front of East High. It felt right to go there after closings. The building has the slightly defeated grandeur of American public education—big windows with chipped paint, banners declaring values no budget can fully fund, a lobby bulletin board with flyers for tutoring and a picture of the chess club captain holding a trophy like a baby.

I found Dr. Martinez in her office working through a mountain of paperwork. “You free?” I asked, peeking around the door.

“For the man who just endowed my dream?” she said, smiling. “Always.”

We walked the hallways like citizens revisiting a revolution site. At the end of the old wing, a door stood closed that had been a dark closet for decades. She pulled a shiny new key from her pocket and turned it. The room glowed. Shelves. Archival boxes. Tables. A glass case with white gloves inside. A poster on the wall: History Lab—Hands On, Minds On.

“You work fast,” I said, throat suddenly full.

“Grants with strings attached move quickly,” she said dryly. “The string being ‘we’ll send you more if you spend it well.’”

We stepped inside. She ran her palm over a clean tabletop like it might purr. “You know, when I started teaching, we had a set of textbooks that still said ‘Soviet Union’ and a map missing three countries. This—” she gestured “—is a cathedral.”

I laughed. “It’s shelves and tables.”

“It’s a place that says to a kid, your questions deserve furniture,” she said.

I nodded. “We’ll launch publicly next month. The foundation’s press team will want a photo. You, me, a student with a primary source in her hands.”

“Primary source,” she repeated, savoring it. “My favorite phrase.”

We stood there breathing the smell of new wood and possibility. On the drive back to the lake, I realized how light I felt in the parts of me that used to be heavy.

At the lakehouse, I found a crate in the study labeled Foundation — Education in my grandfather’s hand. Inside: his notes from meetings thirty years ago, outlines for ideas he never got to build, program names he’d tested and scratched out, budgets written in pencil and then retired for ideas that brought more joy than ROI.

One loose page, at the bottom, with a line that hit me in the sternum: Money does the work only if character points it in the right direction.

I took the page down to the dock as the day dropped its color into the water. A loon called. Pine needles whispered. My phone buzzed. Mr. Hines again: Board unanimously approved the first tranche for the History Lab. Also, a reporter from the Business Journal wants a quote about the foundation’s direction.

I typed: “We’re investing in teachers as if they’re infrastructure—because they are.”

He responded with a thumbs-up, which looked funny coming from a man who writes letters with a fountain pen.

The sky bruised in that beautiful way it does before a storm. I stayed until a heavy drop hit the page. I folded the note and slid it into my pocket and went inside, closing the study window against the weather.

Two mornings later, I walked into the coffee shop on Main Street and felt twenty heads swivel. Fame is very small in cities like ours; it isn’t really fame so much as proof that people read the paper. I ordered a black coffee with one sugar and carried it to a table by the window. I opened my laptop to notes for a meeting with a local district and answered three emails from teachers writing sentences that started with I can’t believe I’m asking this and ended with miracles they wanted to try.

A man stopped at my table, hesitant. He was fifty, maybe, with ink on his fingers that didn’t wash off the way it used to. “Mr. Morgan?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, bracing for a pitch.

“I wanted to say thank you,” he said. “Your grandfather gave my dad a job at the factory when he got out of the service. Paid for my clarinet lessons when the factory closed. I play in the symphony now.” He looked down, embarrassed by his own gratitude. “I heard your speech. He’d be proud.”

I swallowed the ball in my throat that rises when kindness hits you unprepared. “Thank you,” I said. “He’d be prouder that you kept playing when the roof caved in.”

He smiled, nodded, and left me with my coffee and the odd sensation that you can inherit more than cash and chairs. You can inherit a way of being that people remember in their bones.

My phone buzzed on the table. A new text, a new name: Caleb Stewart.

Meet? Man to man. You owe me that much.

The audacity made me laugh. Then another buzz: Emma gave me your number.

I typed: No. Do not contact me again.

He responded with a shrug emoji and the words: Your loss. I put my phone face down and thought about appetites again, how some people treat other people as courses in a meal that never ends.

The door chimed. Theo—no, that was a different life; I smiled at the ghost of a thought and shook it off. My life wasn’t a cross-over novel. It was mine.

Mr. Hines called as I stood. “A quick note,” he said. “The Business Journal is running a follow-up. They want to know your ‘vision statement.’”

“Is ‘good teachers without panic’ a vision?” I asked.

“It is,” he said. “But perhaps expand to three sentences.”

I crafted something about dignity and access and the importance of a city knowing its own story. He approved it with an amused hm. “Your grandfather struggled to speak in anything other than plain, useful English unless he was quoting Thoreau,” he said. “You inherited that.”

“I’ll take it,” I said.

“Lucas,” he added, his voice softening in the smallest possible way. “You’re doing well. You didn’t need his money to be this person. But it does allow the person you are to do more of what he would have liked. He understood that equation.”

“I’m beginning to,” I said.

We hung up. I stepped into the morning’s chill and thought, with a clarity that felt like the sky after rain: Phase two is complete.

Phase three wasn’t about Emma, or Caleb, or a gala, or a headline. It wasn’t even about the Morgan name, not really. It was about cabinets and classrooms and the sound a teacher’s voice makes when a grant comes through at the right time. It was about building something that would function without a newspaper story to justify it and without a family myth to sanctify it. It was about taking off masks and finding your own face tolerable.

On my way out of town, I passed the discount grocery store where Emma had seen me weeks ago. A woman in a nurse’s scrubs loaded bags into a toddler-cluttered trunk while a teenager argued with his mother about cereal. Regular life doesn’t pause because someone you loved learned they were wrong about you. The world keeps asking you to be useful or get out of the way.

I drove north, windows down despite the cold. The pine smell met me a mile out. The lake lay ahead, the color of slate, honest as a ledger. I parked beneath the old sugar maple that turns crimson in October, and as I climbed the porch steps I thought about the simplest of the truths my grandfather had pressed into my teenage hands like a contraband note:

Be the person you would have wanted to inherit from.

I unlocked the door and went inside to begin.

Part III

The History Lab launched on a Tuesday morning in April.

East High’s auditorium, usually a place for dusty assemblies and rainy-day gym classes, had been scrubbed and strung with banners. The new shelves gleamed, stocked with archival kits and replicas: Revolutionary-era newspapers, Civil Rights posters, even a few carefully protected original letters. Students filed in, wide-eyed, phones raised like periscopes.

Dr. Martinez opened the ceremony with the grace of someone who had balanced thirty years of budgets with chewing gum and miracles.

“Education is often spoken of in terms of scarcity,” she said into the mic. “Today, we speak of abundance.”

Then she gestured toward me.

“And now, Mr. Morgan—though to us, he’ll always be Mr. Reed.”

Applause. Whistles. A few shouts from the juniors in the back. I stepped up, tugging my jacket straight, and looked out at faces that reminded me why I’d stayed in a classroom long after my bank account could have excused me from it.

“Good morning,” I began.

“You know me as your teacher. That part hasn’t changed. What has changed is the size of the toolbox I get to bring to you.”

I told them about the initiative—about field trips to archives, guest historians, the chance to handle real artifacts instead of seeing pixelated scans. I reminded them that history isn’t just names in boldface, but people like them who once thought their choices were too small to echo.

“Your questions deserve furniture,” I said, stealing Dr. Martinez’s line. “Now you have it.”

The room erupted in claps. A few kids stomped their feet. The sound reverberated through the floor like a promise.

The next morning, I opened my email to a name that had been a shadow for months: Caleb Stewart.

Subject line: Man to man.

The message was smug in its brevity:

We should talk. Public’s confused. Emma’s confused. Maybe we can sort this like adults.

I deleted it without reply. An hour later, as if the universe wanted to test my resolve, I spotted him outside the museum café where I’d scheduled a board lunch. He leaned against a car too shiny for his means, sunglasses perched on his head, the practiced swagger of a man who believed every room was waiting for his entrance.

“Lucas!” he called, loud enough for pedestrians to turn. “Or should I say Mr. Morgan?”

I paused, holding my briefcase like an anchor. “Mr. Stewart.”

“Come on, don’t be cold. We’re practically family.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Family leaves when the checks stop, doesn’t it?”

His grin faltered. “She told me you’d say something like that. You’re bitter, man. Why hang onto it? We all moved on.”

I let the silence stretch until his bravado wobbled. Then I stepped closer, lowering my voice so only he could hear.

“I am not your stage. Whatever story you’re selling now, sell it without my name. If you use it, you’ll regret it.”

The sharpness in my tone cracked his mask. He laughed, too loud, and backed toward his car.

“Your loss,” he muttered, climbing in.

I watched him drive away, exhaust sputtering. He was already a footnote, and he didn’t even know it.

Two weeks later, a courier arrived at the lakehouse carrying another envelope in handwriting I knew like muscle memory. I thought about tossing it into the fireplace, but the weight of unfinished things pressed against me. I opened it.

Lucas,

This will be the last time you hear from me. I promise. I’ve embarrassed myself enough, chasing ghosts and headlines. I wanted to leave you with honesty—the kind I never managed in person.

You were a good husband. Better than I deserved at the time. I let voices—my mother’s, Caleb’s, even the ones on my phone screen—convince me that contentment was failure. I mistook your steadiness for stagnation. I see now that I mistook a foundation for a cage.

I don’t expect forgiveness. I just hope that one day, when you think of me, it won’t always taste like betrayal. Maybe just regret.

Take care of the legacy you carry. You were always more Morgan in character than in name. Now you’re both.

—Emma

I folded the letter and placed it in the drawer with the first. A matched set of closure. Then I locked the drawer. Not out of anger—out of completion.

By summer, the History Lab was running three pilot programs across the district. I sat in classrooms watching students examine facsimile World War I letters, their fingers brushing the paper as if the ink were still drying. One girl whispered, “This looks like my brother’s handwriting.” Another asked, “Did this soldier survive?” When the teacher said no, the boy set the letter down carefully, like laying flowers.

At a board meeting, I proposed expanding the initiative statewide. Some members balked at the cost until Dr. Martinez herself presented data showing attendance spikes, test score improvements, and—her favorite metric—smiles in hallways.

The motion passed. The budget doubled. For the first time in years, teachers emailed me not with desperation but with ideas.

Sometimes, late at night at the lakehouse, I’d look in the mirror and think about the dual names: Reed and Morgan. Emma had loved only one of them. My students had known only the other. Both were me. But neither defined me as much as the work did.

I sanded wood in the garage, the curls falling at my feet, and realized: money can build tables, but hands still have to steady the plane. Legacies are useful only when you choose what to do with them.

At the next annual gala, I walked the same marble floors, this time with no ghosts lurking at the doors. Mr. Hines introduced me not as the “new” head but simply as the steward. Reporters asked about investments; I talked about field trips. They asked about social prestige; I talked about kids who deserved to hold history in their hands.

And when the lights dimmed for dinner, I caught my reflection in the glass. No beard now, no performance of ruin. Just me.

The Ending I Needed

On a September evening, I returned to the dock behind the lakehouse. The air was crisp, the water catching the last flare of sun. I carried my grandfather’s note in one pocket, Emma’s letters sealed in the locked drawer upstairs, and the foundation’s future in a folder on my lap.

I breathed in the pine and the cool and felt something I hadn’t in years: peace without condition.

Emma was gone. Caleb was irrelevant. The masks had been discarded. What remained was the work—students, teachers, history waiting to be handled and understood.

I whispered into the dusk, to the man who had prepared me for all of this:

“I’m using it wisely, Grandfather. Just as you asked.”

The loon called across the lake. The sky deepened into indigo. And I smiled, not a hidden one this time, but the kind you allow the world to see when you know you’ve stepped fully into the life you were meant to inherit.

News

He Walked Away From Our Wedding to Be With My Cousin—But Life Had Other Plans CH2

Part I I used to think silence was empty. That it meant nothing was happening.But on my wedding day, when…

At our wedding, his childhood sweetheart announced that he had helped her shave down there CH2

Part I The first knock wasn’t a knock so much as a drumroll—fast, jittery, the kind of sound you hear…

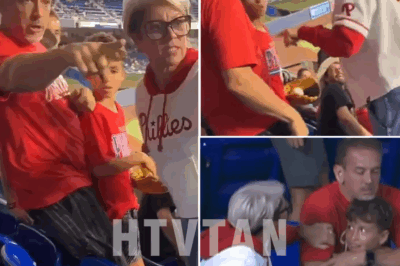

FAMILY SPEAKS OUT AFTER WOMAN IN PHILLIES HOODIE SNATCHES HOME RUN BALL FROM CHILD AT CITIZENS BANK PARK, SPARKING NATIONAL OUTRAGE, INTERNET SLEUTHING, AND DEBATES OVER FAIRNESS AND DECENCY IN AMERICA’S PASTIME

When fans file into Citizens Bank Park to watch the Philadelphia Phillies, they expect a night of excitement, maybe a…

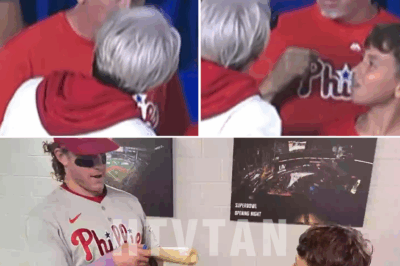

BREAKING: WOMAN DUBBED ‘PHILLIES KAREN’ SPARKS OUTRAGE AFTER SNATCHING HOME RUN BALL FROM CHILD DURING PHILLIES GAME, PROMPTING CALLS FOR CONSEQUENCES AND IGNITING A NATIONWIDE DEBATE OVER FAIRNESS AND DECENCY IN SPORTS CH2

Baseball has long been considered America’s pastime, an arena where family traditions, neighborhood pride, and generational memories converge. It is…

WHO IS THE MYSTERIOUS WOMAN DUBBED ‘PHILLIES KAREN’ WHO SNATCHED A BALL FROM A CHILD AT A PHILLIES GAME, NOW BEING OFFERED $5,000 IF SHE RETURNS IT WITH AN APOLOGY CH2

In a broadcast moment charged with political gravity, Fox News contributor Jessica Tarlov found herself unusually quiet on the day…

SHE GRABBED THE BALL, THE CROWD ERUPTED, AND NOW THE INTERNET IS CHASING THE WRONG WOMAN IN A PHILLIES HOODIE, SPARKING CONFUSION, OUTRAGE, AND A MYSTERY THAT WON’T DI/E CH2

Tarlov Was “Silenced” by Fox News When Trump’s $90 Billion Deal Was Signed On a day when national attention was…

End of content

No more pages to load