Part I

It was 3:17 in the morning when she assumed I was asleep. I lay on my right side, facing the wall, the blue digits of the alarm clock painting the ceiling like a cold, precise wound. When the front door gave a faint creak, I slowed my breathing the way a kid slows his steps on creaking stairs. Boots thumped off just inside the threshold—then a softer sound, heels. She carried her shoes like contraband down the carpeted hall. She set them down in the corner of the bedroom with the hush of someone who knew where the squeak lived in every board of this house.

When she leaned over to set her phone on the nightstand, a cloud of cologne reached me. Not mine. Not anything I had ever worn or would wear. It smelled like whoever-it-was wanted to be noticed without ever having to speak.

The mattress dipped as she slid under the covers. A satisfied sigh, the kind that says a night delivered. The sigh didn’t belong here. Not in our room. Not between the lamp she’d insisted on when we crossed the Mall of America like we were doing something permanent and the ring dish that had collected bobby pins for four years. She lay on her back and let the silence drink her. She believed in darkness as cover and my quiet as permission.

But I was awake. I hadn’t slept through a single suspicious change in her schedule for two months. The urgent late meetings that produced nothing but a new lipstick. The text that arrived while she was in the shower, the lock screen lighting like a flare: B: 11 tonight? Same place. The way she started putting her phone face down, then in a drawer, then in her purse as if the world were suddenly made of thieves. The restaurant charge on a Monday at eight-forty-five p.m. when she’d told me she was eating in the office. The hotel receipt under an alias that looked familiar because it had once been part of a joke between us—a nickname from the summer we went to concerts three nights in a row and pretended we’d invented love.

The same tricks she’d used to ignite us were now gasoline for someone else.

I didn’t speak. I didn’t flip the lamp and demand an inventory of her lies. I let the night land. Sometimes silence is a weapon too—a cleaner one. The next morning I made coffee. I poured some for her the way I always had. I kissed the top of her head. She smelled like a hotel hallway. She said thanks without looking away from the sink as she blotted her lipstick and kept blotting until the tissue looked like a confession.

That night, an “emergency networking dinner” popped onto her calendar at 5:12 p.m. She replied “Of course” to the invite with the little champagne emoji she only used when she wanted to signal a mood. Ten minutes later she was stitched into a black dress that knew her body too well for the hour. She pressed a kiss to my cheek, and the cologne nested in my skin like a dare. “Don’t wait up,” she said, smiling in a way that asked me to want her even as she walked away.

As soon as the door sighed shut behind her, I started moving. Not the sort of frantic flailing they put in movies—shoving clothes into trash bags, toppling picture frames as evidence of moral clarity. A different kind of moving: efficient, practiced, as if my body had been planning this walk for weeks. The envelope sat on the desk already addressed, my attorney’s careful printing neat in the corner. I slid the papers out one more time, not because I doubted the plan, but because one last look is a ritual before you leave a place you built. Our names. Our date of marriage. The words that turn vows back into neutral language. Irreconcilable differences. That phrase holds everything and announces nothing.

I signed where my name belonged in a hand that felt like it belonged to me again. I dated the line. I set the envelope on her pillow, the pillow she fluffed every night like it required her blessing to hold her head. I printed a sentence in thick black marker above the flap. The ink bled a little into the paper fibers, fat and final.

I hope he was worth it.

Then I went room by room and pulled myself out of the life we’d spliced. My side of the closet went first, the row of shirts with the same collar shape because I am a creature of habit and she has always mocked that in a way that sounded like love until it didn’t. The lower dresser drawers that held the T-shirts I should have thrown out years ago but didn’t because they felt like an archive—I emptied those next. The safe, where the passports lived next to the cash we didn’t spend because we were responsible. The file box marked BILLS. My name slid off the lease and the utilities with a surprising ease; when the property manager picked up, he said, “I’m sorry to hear that,” the way people say it to the obituaries in their morning paper.

I stood in the living room and turned once, slow. The wedding photo she insisted stay in the middle of the mantle was still there—her head thrown back, me looking a little stunned, the world blurry around the edges because the photographer believed in bokeh more than context. I took the photo down, not to punish, but because I didn’t want my last image of our living room to include a promise that had been turned into a prop.

The bed looked wrong with only one side stripped: my side. The empty mattress showed the divot where I slept, proof that bodies leave a record of their faithfulness. I tucked the envelope into the depression her head would make when she reached for sleep believing the night was an accomplice. I dimmed the lamp to the level she liked when she came in late and said, with mock-dramatic flair, “I need low light and strong tea.” Then I left.

I backed the car down the street and parked under the maple with the split trunk. From there I could see the bedroom window, the blinds slatted but never closed the way I had asked for a hundred times. At 11:58, the headlights ghosted across our living room walls. At 12:04, the bedroom light snapped on. Her silhouette froze. Risk cracked open her night. I watched her hand reach for the envelope because you can tell the arc of a person’s arm even in darkness. Her shoulders rose, stopped rising. A minute, maybe two. She sat on the edge of the bed the way you sit on the edge of terrible news.

I didn’t go in. I wanted to see her face. I’d pictured it a hundred times, the way a person reenacts an accident to prove he remembers. But sometimes mercy is not giving yourself what you’re hungry for. I let the moment play through a pane of glass and twenty-seven feet. Then I turned the key, checked the rearview, and drove away.

Her calls started at 3:41—first one, then five, then thirty by dawn. I watched them stack on my screen like bad math: Where are you, Pick up, This is crazy, Don’t be like this, We can fix it, Who told you, You’re scaring me. The voicemails built their little narratives: panic, then bargaining, then anger she thought she had the right to. I let them sit. I didn’t listen to the end of any of them. There was nothing in those messages I needed to hear to understand what I already knew.

By sunrise I was two towns away at a guest house tucked behind a tire shop that had been there since 1956, if the sign could be believed. The owner, a woman with forearms that said she moved furniture by herself, handed me a key without asking why my eyes were the way they were. The room smelled like cedar and old towels, and the window framed a slice of sky that knew how to reveal a morning without asking for applause.

I slept. Like a person. Like a person who had been trying to sleep next to a lie and finally found a bed that did not ask him to perform rest.

The first morning there, I did something that felt illegal: I took my coffee to the window and watched the sun clear a row of low buildings and thought about nothing. No narrative. No “what if.” No “how could she.” Just steam, birds, and the tint in the sky that says you still get days no matter what you did to the last one.

Freedom arrived with an ache. That first night in the guest house, I cried into a pillow that didn’t care who I was to it. I shouted once—not a word, just the throat-sound a person makes when he recognizes the shape of his own grief. I mourned the marriage and the man who had stayed to tend its illusions long after the plants had died. I admitted out loud for the first time that I had known longer than I claimed I had. The knowing had been a drip, not a flood, and I’d kept moving a bucket to catch it instead of fixing the roof.

Two weeks passed. I did not pick up. I called my attorney. I called the bank. I walked the small downtown like I was learning a language everyone else had been born into. A diner with four stools and a waitress who called me honey without making a theater of it. A bookstore that smelled like patience. A hardware store where the owner wore an apron like it was a credential.

Friends texted in cautious bursts. You okay? We heard…? Is this a fight or a real thing? I answered them the same way every time: Ask her. If you want the story, ask the person who gave it its plot. I refused to audition for sympathy.

Word traveled. It always does, especially when people want to cast themselves in some benevolent role. She didn’t confess a betrayal. Of course she didn’t. She told a different story about a man who left without warning, cruelly, who “shut down” and “wouldn’t talk,” which is the kind of sentence people admire because it sounds like therapy and discipline at once. She told them I had become cold overnight. She left out the part where heat had been redirected toward newer rooms.

I listened to none of it firsthand. I learned what she said from the tilt in people’s questions. Are you sure you don’t want to try to work it out? She’s really struggling. Everyone makes mistakes. That’s the thing about “Everyone makes mistakes”—it’s always said by someone who is not suffering yours.

On a gray Thursday morning the sky snapped into a blue so blatant it felt personal, and I opened the cabin door with a coffee mug in my hand and there she was: no makeup, hair tied back, eyes swollen in the way sleep makes people honest. She looked smaller. Not because I needed her to. Because that’s what regret does to bone.

“Please,” she whispered, voice threaded with a thousand what-ifs and three thousand what-now. “Can we talk?”

I stepped aside. Not because I owed. Because I wanted to be done.

She crossed the room like a person who didn’t trust the floorboards in a strange house. She glanced at the bare wooden walls, the small sink with the mismatched bowl drying beside it, the twin bed I had been making every morning as if order could convince sorrow to leave. We sat in two chairs that didn’t belong to either of us. She folded her hands. For a minute, we were quiet in the way people get quiet when they remember their throats can hold hurt and breath at the same time.

“It wasn’t supposed to happen like this,” she said. “I don’t even know how to tell it in a way that makes sense.”

“You don’t owe me a story,” I said, and surprised us both.

She laughed without humor. “I owe you a hundred stories. I feel like something was missing in me. He—” she swallowed “—he made me feel alive. Like I could still surprise myself.” She wiped at her eyes, impatient with her own tears. “I kept telling myself I’d tell you. And then I kept not telling you. I didn’t want to be the person who blew up a good marriage.”

“You didn’t blow it up,” I said. “You flooded it. Then you waited for me to learn how to swim in it and call the water a spa.”

She flinched. “You’re cruel when you’re right.”

“I’m not trying to be.”

“I thought—” She stared at the table for so long I thought she’d changed her mind about speaking. “I thought maybe you didn’t want that part of me anymore. The part that wants… heat. Risk. I thought you were happy with routine.”

“I was,” I said. “Happy with it. I thought you were too.”

She nodded like that was a confession in itself. “I wish I could tell you it meant nothing. But it did. And that’s the worst part. It meant something, and it still wasn’t worth what it cost.”

The guest house was quiet enough to hear the highway in the far distance and the occasional fly trying to break its own neck against the window. I hadn’t rehearsed forgiveness. I hadn’t rehearsed rage either. I had rehearsed only one sentence. Seven words. I’d been weighing it in my mouth for two weeks to be sure it fit.

“You lost me the moment you lied.”

She looked up as if I’d flicked a light. There was no drama in her face—no hands to the throat or gasp. Just the collapse that happens when a person’s body recognizes truth before her mind wants to admit it.

She reached for my hand the way people reach for doorknobs in the dark—habit, hope. Her fingers hovered in the air because my hand didn’t move. The space between our palms was full of every promise we had ever tilted toward and missed.

I stood. She followed my rising without thinking, the way people stand in courtrooms when a judge enters. I walked to the door and opened it. The morning air came in like a new rule.

“Goodbye,” I said. That’s all. No You did this. No I’ll be okay. No But remember. I didn’t give her the comfort of making me big in her leaving. I didn’t give myself the thrill of an eloquent exit.

She didn’t plead. She didn’t throw herself at my knees. She just stepped out onto the small porch and into the cold. Her arms crossed over her chest like a person realizing the only coat she had was the one she forgot to bring. She stood there for three seconds longer than was dignified and then she walked to her car without looking back.

When the door clicked shut behind her, the room took a deep breath. So did I.

I poured my coffee out in the sink and watched the final dark ribbon run down the porcelain. Out of habit, I turned to tell someone to pick up the milk on their way home.

There was no one to tell. I stood in the silence, and for the first time in months it belonged to me.

Part III

Ruth said the bread would keep me honest, and she was right. Living above a bakery rewires your mornings. The mixer starts at 3:10 and sounds like stubborn hope. Flour sighs. A bell rings whenever Luis opens the back door, no matter how gently he tries to catch it. At 6:00, the first loaves come out, and the whole street remembers what warm smells like.

I learned the sound of my own steps on the stairs. The second riser clicked under my heel. The landing held chill longer than the rest. I kept my place clean the way people keep something they were told not to touch. I built a habit of putting my phone face-down and walking away from it. My days grew bones.

Mendez called to say the final filings had been stamped and accepted. “You’re legally single,” he said, like announcing weather.

“Feels like being legally vertical,” I said.

He chuckled. “I tell people there’s no such thing as closure,” he said. “Turns out there is. It looks like a clerk who eats almonds at her desk and doesn’t care who you loved.”

I went downstairs and bought a loaf I didn’t need. Luis slid it across the counter with a conspirator’s nod. “On the house,” he said. “For your divorce.”

“How did you—”

“You look taller,” he said, and then grinned. “Ruth told me.”

That night, I did something that felt daring in the small way that matters: I texted six people and told them to come for dinner. Ruth came first with a jar of pickled something that looked like it could start a fight and win. Cliff followed carrying a folding chair like it was a violin. Mel appeared from nowhere wearing a Bayside Storage T-shirt and holding beer as an apology for every grunt he’d given me. Nia drove in with a dessert and three opinions. Luis arrived last, late, with flour in his hair and a pot of beans that smelled like a story.

We ate around my grandmother’s table under a lamp that tried its best. The headboard I’d made leaned against the wall like a quiet achievement. When the plates scraped empty, Ruth raised her jar.

“To bread,” she said.

“To bread,” we said.

“And to the man,” Mel added, “who learned how to sit in his own room.”

“Fine,” Ruth said. “To rooms with doors we own.”

We clinked and laughed, and the sounds hit the glass and came back gentle. The table took our elbows and didn’t complain. I looked around at the faces of people who would not have been in a photo of my life a year ago and felt the kind of presence that doesn’t need Instagram to prove it happened.

Halfway through the beans, a text lit my phone face-down, and I didn’t flip it over. Later, when the dishes were stacked and the air had gone comfortable, I checked it. Adrienne.

HR closed it, she wrote. He’s out. She’s suspended—six months without pay and a demotion. I’m not sending this so you can gloat. I’m sending it because I told myself if there were consequences, I would tell the truth to everyone I lied to. Consider this me being consistent.

I stared at the words long enough to feel compassion move through me like a slow animal. I didn’t feel triumph. I didn’t feel vindication with its cheap glitter. I felt relief on behalf of the part of the world that works better when lies cost something.

Thank you, I typed. For telling me. I’m sorry for what it took to get there.

Me too, she wrote. I bought myself a ceramic mug today. Bright yellow. Felt like a ceremony.

Bread helps, I wrote, and sent her the address anyway, in case she ever needed to be an adult within striking distance of sugar.

After midnight, the table looked like a battlefield that had happened to good people: crumbs, a fork under a chair, a napkin folded the way women fold things when they know hands can make order out of anything. I set the plates to soak and stood in the window, city doing its neon impression of Orion.

There was one thing left. I’d avoided it so completely the avoidance had weight. The storage unit still held a small stack labeled BEDROOM. Her mother had offered to pick up the rest and had done it with the quiet grace of a person who knows her voice can wound without volume. The box remained because the release form required both signatures, and because Ruth had said, “You should be the one to close your own door.”

The next morning, I texted her mother. I’m coming by the apartment at noon for the last box. I don’t want to run into her.

She answered a minute later. I’ll make sure she’s gone. Gate code hasn’t changed. I’ll leave the door open. The bedroom light is finicky—tap twice.

At 11:58, I parked under the maple with the split trunk. The slot of sidewalk between the buildings still held the same oil stain. The stairs still bowed inward where people carried groceries with one hand and opinion with the other. I walked up them like a tourist in a ruin.

The door was cracked, as promised. The apartment smelled like citrus and a candle trying too hard. The living room had been rearranged into a new story. The couch belonged to someone else. The mantle held a new photo of a beach that could have been any beach, and a plant trying not to die. The ring dish on the nightstand was gone. The lamp I’d dimmed that last night had a new shade that pretended history can be softened by fabric.

The box sat on the bed. The quilt—her grandmother’s—was gone, and I was glad for it. Some things should be kept out of arbitration. I lifted the lid and saw what the box wanted me to see: my last shirts, a book I thought I’d lost, the playbill from a concert we’d both lied to our bosses about to attend. Underneath, flat as paper tends to be, lay the envelope. The one I’d left on her pillow. I recognized the corner where the ink had bled into the pulp. I recognized my own handwriting, big and blunt, I hope he was worth it.

For a second I couldn’t move. One step into our bedroom changed me again—not back, not forward, but sideways, into a place where pity and clarity stood on either side of me like bouncers. She had kept the envelope. Not thrown it away in rage, not shredded it in a domestic ritual, not mailed it back to me with curses. She had kept it, flat and quiet, in a box that waited.

I picked it up. It wasn’t heavy, but my hand learned something about weight anyway. I slid a thumb under the flap and found nothing inside. Whatever rupture had been announced there had done its work and moved on. I folded the flap closed again, not to save it—there are some things that cannot be saved, only acknowledged. I set it on the dresser for her to find again, if she needed to. A relic, not a relic to me.

On the nightstand, under the pad of paper where she used to write lists that always included call Mom, I found a key. My key. The one I’d given back to the property manager. I picked it up and felt the old muscle memory hum: right, lift, turn, sigh. I put it in my pocket. Not to use. To carry it to Ruth’s house and leave it on her kitchen table and call it a souvenir of the person I used to be when I thought keys opened anything but doors.

On the way out, I stood in the hallway where we had stood hundreds of times: with groceries, with anger, with plans we’d write on napkins and then forget. I tapped the light switch twice. It flickered and then steadied. The bedroom paused in that even light and showed me a room without me in it. I let my eyes adjust to reality.

In the doorway, her mother watched me with a face that could only have been built by time and a thousand small disappointments in people she still loved. “You’re kind,” she said.

“I’m not,” I said. “I’m just done.”

“That’s a kind that should be taught to children,” she said.

She hugged me the way someone hugs family at the end of a funeral—one arm hard, one soft. “Go home,” she said. “Your bread will burn, and I couldn’t live with myself if I made you ruin toast.”

Back upstairs, I set the key on Ruth’s table. “Souvenir,” I said.

She glanced at it, then at me. “You don’t collect those,” she said.

“No,” I said. “I don’t.”

I went next door to the woodshop and put my hands on something that had nothing to do with vows: sanded pine. Cliff watched me for a minute and then handed me a rag with walnut oil.

“Rub it in,” he said. “Not too much. Let the wood drink what it needs. Wipe the rest. Don’t leave it tacky.”

There are entire marriages in that instruction.

That weekend, Adrienne texted again. I’m taking a weekend. A cabin by a lake. No reception. Just me and a yellow mug.

Good, I wrote. Bring bread.

Already packed, she wrote. You know, we don’t have to be friends.

We don’t, I wrote back. But we can be people who know where the other person keeps the spare truth.

She sent a photo: the mug, the lake. Water complicates things, but sometimes it translates.

A week later, under a sky that couldn’t decide between rain and showing off, I walked to the farmer’s market and bought basil because I could. I bought tomatoes that would punish me if I forgot them on the counter. I bought peaches that bruised when I looked at them wrong and let me feel, for a minute, careful.

On the way home, a man stepped out of the hardware store and nearly collided with me. He apologized. I apologized. We did that sideways dance people do when the sidewalk insists on choreography. He grinned, and it was a grin that said he wasn’t trying to be cute so much as he couldn’t help it.

“Sorry,” he said again, as if sorry were a hobby. “You live upstairs?”

“I do,” I said.

“I’m Sam,” he said, holding out a hand that looked like it had known both keyboards and wrenches.

“Hi, Sam,” I said, and shook it. It fit in mine in the way that didn’t predict anything except that hands are designed to meet.

“I’m late to fix a hinge that isn’t going to wait,” he said. “But—welcome to the block. If you need a drill at an odd hour and don’t want to buy one, I have opinions and a toolbox.”

“I have a table that needed legs,” I said, and then caught myself. “It has them now.”

“Good,” he said. “Tables that stand are less likely to become metaphors.”

He jogged across the street and turned into the alley behind the hardware store. A minute later I heard the ratchet click. The sound traveled like a radio station playing something I was finally in the mood to hear.

Back upstairs, I set the basil in a jar of water and the tomatoes on the table and made toast. Butter made a map of the bread. I ate standing at the counter with the window open. Somewhere down the block a child refused to nap with gusto. Somewhere two floors down, sugar became dough. Somewhere across town, a woman I had loved was learning that shame and change are not the same thing.

I put on my shoes—the ones Ruth said didn’t do anything they didn’t have to—and walked back to the storage unit. I opened the roll-up door and looked at the boxes I had labeled with a mixture of optimism and sarcasm. I took out the last one marked NOT A BOMB. JUST HISTORY and opened it. Inside lay the wedding photo I had refused to give to a thrift store because someone else’s vows should not be a stranger’s décor. I held it up to the strip of light and then, carefully, I wrapped it in the Sunday comics from that week. I taped the box shut and wrote one last thing in black marker:

ARCHIVE. OPEN RARELY.

On the way home, I stopped at the diner. The waitress refilled my coffee without asking, because that’s what she does when you walk in looking like you’ve finally put a decision somewhere it can sleep.

“You look taller,” she said, because people in this town were determined to make it a chorus.

“Must be the shoes,” I said, and smiled, because we both knew better.

The phone buzzed once more that afternoon. A number I still knew, even without a name. The message was short.

I’m leaving the city. New job. Different coast. I’ll make it make sense. Thank you for not making me a villain to everyone.

I stared out the window for a long time at nothing in particular and then typed the last thing I would ever send her.

I hope you become someone you can live with.

No introduction. No sign-off. No weapon. Just a wish I didn’t expect to hear back from. I tapped send and put the phone face-down. It stayed quiet. That felt like the world finally learning the boundary it had been testing.

That evening I carried the basil to the table and called Nia. “Dinner?” I asked.

“Always,” she said. “What’s on?”

“Beans,” I said. “Bread. Tomatoes that will make us apologize for every bad tomato.”

“Sounds like absolution,” she said.

We ate with the window open and the radio on low. The streetlights came on one by one like a patient idea. When the plates were empty and the basil had given up a little of itself to the air, I stood and turned out the lamp. The room held shape in the dark. My bed—my headboard—waited without making demands. The table looked back at me like the solid thing it was.

I brushed my teeth and set my phone on the dresser and didn’t look at it again. I lay down and listened to the mixer downstairs stutter into the night shift and felt my body choose sleep. In the middle distance, a hinge clicked and then settled. Somewhere, a door closed. Somewhere else, another opened. Not because anyone said the right lines, but because wood and gravity and choice, working together, have their own kind of mercy.

In the morning, at 3:17, the mixer started. I woke, rolled over, and went back to sleep.

When I got up at six, the sky had it in mind to be blue. Bread cooled on racks in the window below. I brewed coffee and stood at the table and wrote a list on the back of yesterday’s receipt.

Call Mom.

Oil headboard.

Buy peaches.

Return Mel’s dolly.

Text Sam about drills.

Keep the door closed.

I folded the list into my pocket. I locked my door on the way out, not because I was hiding from anything, but because some rooms you guard for the person you’ve finally let live there.

On the sidewalk, Ruth handed me a loaf without ceremony. “For the hinge,” she said.

“What hinge?”

“The one that’s going to hold,” she said, and turned toward her garden hose as if it had asked for her opinion.

I walked toward the day. It met me halfway.

THE END

News

He Said ‘It’s Just Baby, You’ll Be Fine’ and Went Out With Mistress Next Morning His Boss Called… CH2

Part I The contractions began the way summer storms do—distant at first, a rumor in the sky—then suddenly right on…

His Wife Screamed: “Don’t You Dare lecture my kids”—But His Revenge Left Her Speechless… CH2

Part I: The smell of garlic and butter should have softened the night. The lasagna was still steaming in the…

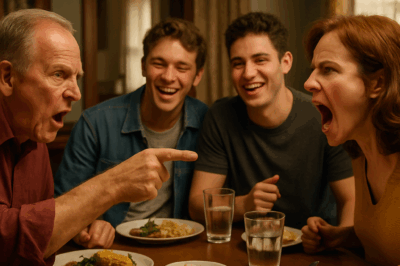

At Family Dinner She Said, “He Means Nothing” — Then Froze When I Put the Photos on the Table… CH2

Part I: The smell of roasted chicken and garlic bread had always meant comfort. For years it was the background…

He faked his disappearance just to play a trick on me, yet I flew to the US with his best friend… CH2

Part I The second month after my boyfriend “went missing,” I saw him. By then, the flyers with his photo…

MY WIFE ABANDONED ME AND OUR NEWLY BORN TO GO AWAY WITH HER LOVER BUT SHOWED UP LATER. NOW SHE… CH2

Part I The room smelled like antiseptic and formula, that sterile sorrow hospitals press into your clothes and send you…

My Sister Tried To Humiliate Me At The Will Reading – Then Froze When The Judge Revealed… CH2

Part I Two days. That’s all the notice I got. A stiff white envelope sat on my doormat in Atlanta,…

End of content

No more pages to load