The First Goodbye

I used to think intelligence would save me. That if I stacked the right grades and did the right activities and checked all the right boxes—AP classes, varsity math team, the robotics club with the broken 3D printer—I’d earn something like safety. A seat at the table. A softening in my father’s jaw. A touch of pride in my mother’s voice.

When the acceptance letter from Stonemont University landed in our mailbox—a fat envelope for once instead of the slim little condolences I’d learned to expect—I walked it into the kitchen like a miracle. The paper was creamy, the logo stamped in a shade of blue so rich it looked almost wet. I’d rehearsed the revelation a dozen times on the bus ride home, the way I’d say, I did it. I made it. This is my ticket.

My father sat at the head of the table with his phone propped against a coffee mug, watching a video of a guy lifting a barbell so loaded it looked like a prank. The house smelled like lemon floor cleaner and last night’s garlic bread. Mom rinsed lettuce in the sink, humming something from the eighties. Twelve-year-old Isabella, in a messy bun and sparkle nail polish, scrolled her phone and laughed at something I wasn’t invited to understand.

“I got into Stonemont,” I said, sliding the envelope onto the table like it came from a different world, which it did.

My father glanced up. “What’s that cost?”

“Dad.” My voice broke on the word. I swallowed and tried again. “It’s the top computer science program in the state. The career center put their recent grad salaries right on the website. It’s… it’s good.”

He leaned back, arms crossed. Though the kitchen lights were bright, his eyes stayed shadowed—the way they always did when I asked for anything big. “If you were really smart, you would’ve gotten a full ride.”

“Harold,” my mother warned, still humming, as if that word excused everything. She never fought with him when it was about me.

Isabella smirked over the rim of her phone. It wasn’t some cartoonish sneer—just a tiny twitch, the smallest confirmation that she remained orbit and I remained drift. She knew her place had already been secured with birthday cars and dance recitals and the delicate jewelry Mom “just found” for her at Nordstrom. I knew my place too: the kid who did okay for herself without making a mess.

“I got a partial scholarship,” I said, forcing brightness into my voice. “And there’s federal aid. I did the math. If I work in the lab and—”

Dad made a low sound that wasn’t quite a laugh. “We’re not co-signing on any private loans. People’s kids go to college every day without bankrupting their parents. You’ll figure it out if it’s that important.”

“Harold,” Mom said again, rinsing the lettuce, as if the rinse were for me.

It’s funny what your brain remembers during an impact. I remember the lemon cleaner smell. The hum of the refrigerator. Isabella’s elbow on the table, the way she had drawn a star on the back of her hand in glitter pen. My own pulse in my ears. My mouth was still trying to smile.

“It is important,” I said, but my voice sounded wrong even to me, like it came from too far away. “It’s my chance.”

“Then take it,” Dad said, attention already drifting back to the guy straining under all that weight. “With your own money.”

The only person who looked at me like I was a person was the figure framed in the kitchen doorway—my grandmother, Francis. She lived two blocks away in a white clapboard house with squeaky floors and violets that never seemed to die. She had a dish towel thrown over one shoulder, a little white fluff of hair that defied combs, and hands that looked like they could thread a needle in a thunderstorm.

“Show me that letter,” she said.

I gave it to her and watched her face change as she scanned the lines. Her lips softened. Her eyes shone in a way that made me want to both hide and lean closer. “My girl,” she murmured, chucking my shoulder with the same knuckles that had kneaded a thousand loaves of bread. “You did it.”

Mom set the lettuce in a salad spinner. “We’re very proud,” she said vaguely into the sink, as if the faucet needed to hear it more than I did.

Grandma didn’t say anything to either of them. She folded the acceptance letter, slid it back in the envelope, and pressed it into my hands as if the paper were fragile and holy. “We’ll figure it out,” she said to me, and it sounded like a promise made by someone who had kept many promises and knew exactly what the keeping required.

The figuring it out took place in the library, in financial aid offices with gray carpeting, in lines where the fluorescent lights showed you how scrubbed your face really was. I learned about subsidized versus unsubsidized loans. I learned how to fill out forms until your wrist cramped. I learned that you could be accepted into the world and still stand on the threshold looking for a way in.

I brought my father charts and graphs and a spreadsheet with tabs: tuition breakdown, average starting salaries, job placement rates. I printed a list of alumni who worked at companies even he had heard of. He glanced at the stack the way he’d glance at a local coupon mailer. “I’m not co-signing,” he repeated, like a barbell he could lift easily. “It’s too risky.”

I should say this: I wasn’t surprised. I’d been in this family long enough to understand our economy. Love in my house was like a municipal service that worked fine so long as nothing broke and nobody asked for nights and weekends. Isabella’s needs could cancel plans. Mine were… inspirational. Good for newsletter copy. But in emergencies, I was my own ambulance.

The day I left for Stonemont, the air had a high, hard shine. I had packed the Honda with milk crates of folded shirts, two mugs, a blanket, a thrift-store lamp that flickered when you breathed near it. Mom was making a grocery list. Dad was half absorbed by the sports section. Isabella was in the hallway mirror trying on three shades of lip gloss without taking any of them off, so her mouth looked like a stack of shellacked petals.

I stood in the doorway, holding my keys in both hands as if the metal might run away. “I’m leaving,” I said.

“Drive safe,” Mom answered, already scratching “eggs” in loopy handwriting.

No hug. No photo on the front steps, Mom’s cheek against mine, Dad pretending to be stoic. I don’t know why I expected any of it. Expectations are funny—they linger even after you’ve fed them nothing.

I walked out and there she was: Francis, on the porch with her sweater sleeves pushed up like a boxer. She smelled like lavender and the faintest whisper of Wint-O-Green mints. “Hold out your hands,” she said softly.

I did, and she placed an envelope in them. It wasn’t fancy—no logo, no seal. Just a small bulging rectangle already softened by her grip.

“For emergencies,” she said. “You hear me? Not for lattes. Not for some trendy thing you’ll regret in six months.”

I laughed because she wanted me to, and also because I wanted to cry. “Okay.”

She hugged me then, but not gently. She hugged me like she wanted to push something into me through my ribs: certainty, maybe, or a little courage to last the first winter. “They’re fools,” she whispered into my hair. “They don’t know what they’re throwing away. Go anyway.”

I promised I would call. I promised to eat vegetables. I promised to sleep, which we both knew was a lie we could forgive. Then I got into my car and drove toward the interstate, the merest tremor in my fingers, the envelope on the passenger seat like a glowing coal. At the first rest stop, I pulled over and opened it. Two crisp hundreds. The maple leaves on the bills looked almost red in the afternoon light. It felt like more than money. It felt like someone had told me I was worth breaking their budget for.

College nearly broke me anyway.

The campus was beautiful in the brochure way: lawns shaved to velvet, brick buildings with names like Caldwell and Strickson that hinted at endowments and secret handshakes. My dorm room was a rectangle with cinderblock walls painted a color that tried and failed to be cheerful. When my new roommate arrived—with parents who rolled a full IKEA experience through the door and a hug that winded her—I pretended to be very interested in where to place the thrift-lamp.

I sat in the first row of every lecture, the sort of student professors notice if they’re looking. I learned the squeak in Dr. Patel’s shoe meant he was about to ask a question; the way Professor Ullman rubbed his forehead when the class got close to an answer but not quite there; how the lab smelled like solder and dust and the faint metallic tang of ambition.

And I worked. The campus computer lab hired me for twenty hours a week, which is to say I learned what fluorescent light feels like at midnight and how the keyboard keys get greasy under your fingertips after a while. I reset passwords for guys who insisted they never forgot passwords. I helped first-years print a syllabus that jammed the same machine every Wednesday morning. I learned to eat in sprints: a microwave burrito between tutoring sessions; pizza at a club meeting I didn’t have time to join.

On Sundays, my phone would ring and it would be Francis, asking in her brisk voice about classes and friends and whether I’d found anyone worth my time. She didn’t fill silences with her own stories to make mine smaller. She let me talk until I was empty and then she filled me back up. And each month, a card would arrive with a cartoon cat doing something ridiculous and a fifty-dollar bill tucked inside. Sometimes a hundred. “For emergencies,” her careful handwriting would remind me. When I called to say I didn’t need it, she’d snort so loud you could hear it through the receiver. “You’re twenty. Everything’s an emergency.”

I called home for birthdays and holidays like a person who keeps appointments.

“Hi, Mom,” I’d say, balancing the phone between my ear and shoulder while I scraped a plate in the dorm sink. “Happy birthday.”

“Oh, Julia,” she would say, pleasantly surprised to be remembered. “Thanks for calling. How’s school?”

“It’s going well,” I’d say. “I made the dean’s list.”

“That’s nice. Isabella made student council vice-president. She’s so mature for her age. Harold! Julia’s on the phone,” she would shout into the other room. Dad would answer with a distracted “Uh-huh,” and then we would all say we loved each other as if it were a line in a script and hang up before the ads started.

On the nights the lab was quiet and the screensaver galaxies drifted across rows of idle monitors, I would pull up spreadsheets of my loans. Numbers anchor me when nothing else will. I would add new columns labeled “principal” and “interest” and “extra payment” and toy with scenarios the way other girls toyed with shoes. If I worked summer and winter breaks. If I got a better-paying gig second year. If I earned a research stipend. If if if.

The thing about being busy enough is it keeps you from thinking about wanting things. You don’t long for big embraces when your eyes are burning from code and your floor meeting starts in seven minutes and you have laundry tumbling in a machine that eats quarters like a slot. That didn’t make the wanting disappear. It just made it flicker at the edge of the screen like a notification you never opened.

By the time senior year rose up out of the fog, I had a capstone project I was proud of and a reputation as the person who could take someone else’s messy class notes and find the structure hidden inside. I had interviews scheduled with three companies—names my father would recognize not because he tracked the tech sector, but because their commercials ran during football. Professors wrote me recommendation letters that made me blush when I read them in the financial aid office because I didn’t have a printer that week.

Graduation approached like a finish line you can’t quite see but know is there because everyone is running harder than usual. Families descended in packs. They wore polo shirts and summer dresses; they carried balloon bouquets tied to koalas in caps; they cried without trying to hide it. I watched the crowds from the edge of the lawn, in that liminal space where you’re both in the picture and not. I kept scanning for Mom’s red hair that had faded to copper or Dad’s broad shoulders, for Isabella’s easy bounce, but it was like looking for birds in a storm.

The night before, Mom called.

“Hi, honey,” she said, and I could hear cutlery and chatter in the background, the soundtrack of a restaurant you went to for occasions.

“Hi, Mom.” I kept my voice light. “Big day tomorrow.”

“About that.” She hesitated—one of those pauses that act like a trapdoor. “I’m so sorry, but we can’t make it. We booked a cruise for Isabella’s spring break months ago. It’s hard to reschedule those things once you’ve paid.”

“It’s okay,” I said, and I meant it in the sense that I’d survive, not in the sense that anything about it was okay. I stared at the ceiling and pictured the pattern of dead bugs in the overhead light. “Don’t worry about it.”

They didn’t.

Francis drove four hours by herself, wearing a cardigan with little embroidered violets because she said “a woman should be dressed for her granddaughter’s day.” She sat through the entire ceremony, applauding like she’d paid for the whole show, and she took photos on a phone that always had the volume turned up, so each click sounded like a firecracker. Later, she took me to a restaurant with a menu that didn’t list prices. When the waiter poured water in tall thin glasses, I felt like I was playing a part in the life of a richer girl. But it turns out the only thing you need to belong in a place like that is someone who looks at you like you belong.

Three weeks after graduation, I accepted an offer from Blue Tax Solutions. It wasn’t some social media rocket ship with bean bag chairs and kombucha on tap; it was a steady company with an overfull backlog and an IT team that needed somebody who could sweep the corners. They offered sixty-five thousand dollars to start. The number didn’t feel real until I saw the first paycheck and realized I could actually make the rent and have extra. I moved into my grandmother’s spare room while I hunted for my own apartment. The wallpaper was a faded rose pattern; the floor squeaked three steps from the door. I slept like I hadn’t in years.

During those six months under Francis’s roof, my parents came by twice. They admired the azaleas. They asked perfunctory questions. “So you’re working now?” Dad said, as if this was a rumor he’d heard and wanted to see if it held up under pressure.

“At a software firm downtown,” I said.

“That’s good,” he said. “That’s steady.”

They spent the rest of the visit talking to Francis about Isabella—how she’d been accepted to State with a generous package, how she was thinking about marketing and maybe law later if she didn’t like marketing, how she needed a new laptop that could “handle college.”

I got my own place six months in: a decent one-bedroom with peeling crown molding and a view of a brick wall I pretended was art. I bought a secondhand couch that sagged in the middle. I threw every extra dollar at my loans. Friends sent photos from beaches and mountain cabins and weekend jaunts to cities where the taxis were yellow. I didn’t resent them. I had a plan, and plans make even small rooms feel like seed vaults.

Francis kept me informed whether I wanted to be informed or not. “They took a second mortgage for Isabella’s tuition,” she told me one Sunday, her voice half scandal and half “of course.” “They call it an investment.”

I sat down on my sagging couch and stared at the crack in the ceiling I’d come to know like the curve of a hand. An investment. The same two people who told me the smartest move was to go to community college to “get my feet under me” had taken out a second mortgage the minute the golden child shined up a plan. The revelation didn’t hurt the way you’d think. It arrived like the confirmation of a diagnosis you’d suspected for years.

Time accumulated small indignities like lint: the brand-new Honda for Isabella’s twenty-first; the celebratory Hawaii trip after State because “she worked so hard, poor thing”; the way my parents told those stories with a wet glow in their voices, the way you talk when you remember your own wedding day. I said “that’s nice” so many times the words lost meaning.

And then one afternoon, twelve years of sacrifice dissolved into a single line of digits: $0.00. I stared at the student loan balance on my laptop while the blinking cursor waited patiently to become the next thing I typed. I could feel the absence the way you can feel the ocean when you take off wet socks: a sudden weightlessness, the room buoyant around me.

I called Francis before the emotion could talk me out of the simple fact of it.

“Grandma,” I said. “I did it. They’re gone.”

“My girl,” she said, voice cracking like a porch step. “We’re going to celebrate right.”

Saturday night at her place smelled like pot roast and potatoes roasted until their edges went sharp. She hauled the china from the cabinet like a magician revealing a flash of white doves. I showed up with cheap wine and a tuna casserole from the fancy deli that never tasted like her casserole but was good anyway. We clinked our glasses and ate until the only thing left on our plates was a sheen of gravy.

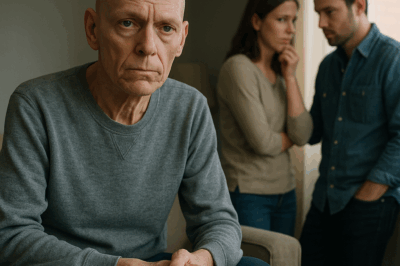

Twenty minutes into that sweet little glow, there was a knock. I was still laughing about something Francis had said—her story about the mailman who’d confided in her about his bowling league drama—when she opened the door. The air in the room changed the way air does before a storm.

“Julia,” Mom said as she swept in, eyes flicking over the table, the china, the wine. Dad loomed behind her, face closed. They had been invited by absolutely no one.

“What’s the occasion?” Mom asked, as if she hadn’t already inventoried it. “Looks like a celebration.”

I swallowed the defensiveness and said the thing plainly. “I paid off my student loans.”

Mom’s lips shaped an oh and then flattened into a practiced smile. Dad’s eyebrows shot up and then settled. There was a look that flickered between them—the kind of look married couples exchange when a new variable enters the budget.

“How’d you do that so fast?” Dad asked, which was funny because twelve years hadn’t felt fast in my body.

Francis jumped in with a cheerfulness that had iron beneath it. “She works at a very respectable firm,” she said, putting her hand on my shoulder. “She’s doing just fine for herself.”

Another look passed. Nods. Then forks scraping plates, polite noises, no more questions. I didn’t know it yet, but that was the moment a new plan began to root in the soil of their minds.

When the dishes were stacked and the leftovers tucked in foil, when I’d kissed Francis’s cheek and promised to call tomorrow, I drove home through the neighborhood that had shaped me. The streetlights blinked on one by one like a row of tired eyes. I parked, climbed the narrow staircase to my apartment, and sat on my couch with my hands folded in my lap like a kid waiting for roll call. Something had shifted. I pressed my palm flat against my chest and felt for the change, but as usual, my body was the last to know.

The Golden Child’s Shadow

The invitation came a week later, sliding into my life with the unnatural cheer of a telemarketer.

“Julia,” Mom said on the phone, her voice pitched just a little too high, “your father and I realized we haven’t seen you much lately. We’d love to have you over for dinner this weekend. You know… to chat and reconnect.”

I nearly dropped the spatula I was holding. In thirty years, my parents had never once invited me specifically to “reconnect.” Birthdays, sure. Holidays, yes—though even then it was mostly because Francis insisted we all gather in her dining room with the lace tablecloth she ironed flat. But this? This was new.

“Uh, sure,” I said slowly. “Saturday?”

“Perfect,” she replied quickly, as though afraid I might back out.

When the call ended, I stood in my tiny kitchen staring at the cabinets that had warped a little from the last tenant’s steam. I could still hear her tone. Bright, determined, rehearsed. Something was up.

Saturday arrived with a sky so clear it made the cracked sidewalks seem sharper. I pulled on jeans from Target and a simple sweater, the kind of outfit I wore when I wanted to disappear. Driving to the beige-sided house I’d grown up in felt like slipping into an old skin I’d outgrown. The hedges were still overgrown, the siding dull from years of half-hearted upkeep. I parked at the curb and sat for a moment, gripping the steering wheel, bracing myself.

Inside, the kitchen smelled of roasted chicken and something buttery. Isabella was at the table, a glossy magazine spread out before her, though she was really focused on her brand-new phone. She glanced up when I entered, eyes sliding over my clothes with the kind of assessment that didn’t need words. Her own outfit screamed designer.

“Hey, Isabella,” I said.

“Hey,” she replied flatly, eyes back on her screen.

Mom bustled from the oven, her voice falsely bright. “Dinner’s almost ready. Julia, tell us about work! How’s the job going?”

What followed was the most interest they had ever shown in my life.

Dad asked about the company’s size, my department, whether I worked with “any major clients.” He nodded like an accountant tallying numbers when I explained my role. “Must be doing well,” he said, watching me closely. “I mean, paying off those loans so fast… that couldn’t have been easy.”

I forced a smile. “I just lived within my means. Put extra money toward the payments.”

They exchanged that look again—the silent conversation I wasn’t supposed to hear. The same one they’d had at Grandma Francis’s table.

Meanwhile, Isabella filled the silence with little barbs disguised as casual observations. “So, you’re still renting that place downtown?” she asked.

“Yeah. It works for me.”

“Isn’t rent kind of expensive there? I mean, you could probably buy something for what you’re paying.” She smirked, as though the thought of me owning property was laughable.

I chewed my chicken slowly, willing myself not to rise to the bait.

A few days later, they showed up unannounced at my apartment. I came home from work to find them standing in the hallway outside my door, Mom with a plastic smile, Dad peering over her shoulder like a building inspector.

“We thought we’d see where you live,” Mom said.

They wandered through my one-bedroom, commenting on the rent, the neighborhood, the utilities. Isabella trailed behind, her tone sugary with sarcasm. “Oh, this place is cute,” she said, running her fingers along my bookshelf. “Cozy. I mean, kind of small, but cozy.”

It felt less like a visit and more like an audit. They asked about my expenses, my savings, the stability of my job. When they left, the walls of my apartment seemed tighter, the air heavier. I stood in the center of the living room, violated and confused.

Why now? Why this sudden interest?

The answer came from Francis.

We were having tea in her kitchen when she put down her cup, her expression unusually serious.

“Julia,” she said, her weathered hands tightening around the porcelain. “I need to tell you something. You’re not going to like it.”

My chest tightened. “What is it, Grandma?”

“My friend Nancy—she lives next door to your parents. She called me yesterday. She overheard them talking on the back porch.” Francis’s mouth twisted, as if even repeating it left a bad taste. “They were discussing how to convince you to buy an apartment for Isabella.”

The words struck like a physical blow. “What?”

She nodded grimly. “Your father said you have no student loans anymore, you make good money, and you don’t have a boyfriend draining your wallet. Your mother agreed—you should help your sister since you have all this extra income.”

I sat back, the pieces clicking into place with sickening clarity. The sudden dinner invitation. The questions about my salary. The inspection of my apartment. They’d been sizing me up, calculating how much they could extract from me.

“I can’t believe this,” I whispered, though deep down, I could. It was the kind of scheme they’d pull without blinking.

Francis reached across the table, her grip fierce. “I’m so sorry, sweetheart. I debated whether to tell you. But you deserve to know.”

“No,” I said firmly, swallowing the lump in my throat. “I’m glad you told me. Now I understand.”

She studied me carefully. “What are you going to do?”

I looked out the window at the neighborhood I’d grown up in, the houses lined up like sentries guarding a childhood that had never truly been mine. My boss’s words came back to me—his casual mention of the new Colorado branch and their need for experienced staff.

“I think,” I said slowly, “it’s time for a change of scenery.”

Francis’s eyes filled with tears. “Colorado?”

I nodded. “I need to get out before they try to rope me into this.”

She squeezed my hand. “Then go. I’ll miss you, but go. And don’t you dare feel guilty.”

For the first time in years, I felt something like freedom pressing against the cage.

The Scam Revealed

The weeks that followed felt like living in two different realities at once.

By day, I went to work, smiling through meetings, debugging code, and drafting proposals. My boss, Marcus, kept hinting about opportunities—bigger projects, maybe a leadership role down the line. He even mentioned again that the new Colorado branch needed people who could hit the ground running. Each time he brought it up, the idea of escape pulled at me like a tide.

By night, I packed in secret. A box here, a suitcase there. I told my landlord I’d be moving out “for work reasons” and arranged everything with a moving company. The flight to Colorado was booked for the morning after the movers came.

I told no one except Francis. She hugged me so tightly I thought my ribs might crack. “My lips are sealed,” she promised. “But oh, sweetheart… I’ll miss you every day.”

“I’ll miss you too, Grandma. But I can’t stay here—not with them circling like vultures.”

She nodded. “Then go. Start fresh. I’ll visit. We’ll talk every week.”

Her blessing steadied me.

Meanwhile, my parents kept calling, pushing for another dinner. “We have something important to discuss,” Mom insisted, her tone sugared but tight.

I knew exactly what they wanted to discuss, so I played along. “I’ve been busy,” I said lightly, “but maybe soon.”

Finally, Mom’s patience snapped. “Julia, we really need to talk. This weekend. No excuses. It’s important.”

I agreed. Because I wanted to hear it directly from their mouths.

Saturday arrived. My boxes were sealed and stacked neatly in my living room, the moving truck scheduled for Monday, my flight on Tuesday. This dinner would be my final act in their play—the last time I’d sit at that table as the dutiful daughter.

When I walked into the dining room, the air was thick with expectation. Isabella practically vibrated with excitement, bouncing in her chair. My parents sat stiff and serious, eyes fixed on me.

“Julia,” Dad began, “we have something important to ask you.”

I cut my chicken slowly, forcing calm into my voice. “Okay.”

“Isabella’s been looking at apartments,” Dad said.

Isabella jumped in, her voice bubbling with glee. “It’s amazing, Julia. Two bedrooms, granite countertops, a balcony with a city view. The building has a gym, even a rooftop deck! It’s perfect.”

I lifted my glass of water. “Sounds expensive.”

Mom leaned forward, eyes shining with false warmth. “Well, that’s the thing. The apartment costs three hundred and fifty thousand.”

I almost choked on my sip. “Three hundred and fifty…?”

Dad cleared his throat. “We’ve been looking at the finances. We just don’t have the money for a down payment and mortgage right now. But you…” He paused, his gaze sharp. “You’re doing well. No student loans anymore. Steady income. No major expenses.”

Mom smiled like she was offering me a gift. “So we were hoping you might help Isabella. Maybe co-sign the mortgage. Or even handle the payments for her until she’s more established.”

Isabella’s grin stretched ear to ear. “Oh my god, Julia, thank you so much! You’d really do this for me?”

The three of them looked at me like predators watching prey, already tasting the meal.

I set down my fork, folded my hands, and tilted my head thoughtfully. “Three hundred and fifty thousand,” I repeated. “That’s a big responsibility.”

“But you can afford it,” Dad pressed. “Easily.”

They had no idea how tightly I’d budgeted, how many nights I’d gone without sleep to pay off those loans, how much I’d sacrificed. To them, my life was just an untapped bank account.

And yet—I smiled. “You know what? I don’t mind helping Isabella out.”

Their faces lit up like Christmas morning.

“Really?” Isabella squealed. “Oh my god, Julia, you’re the best! When do you want to sign the paperwork?”

“The appointment with the bank is next Friday at ten,” Mom said eagerly. “We’ll meet you there.”

“Perfect,” I said, keeping my smile steady.

We finished dinner with Isabella chattering about paint colors and furniture, my parents glowing with satisfaction. They thanked me over and over, saying how proud they were that I was “stepping up to help family.”

I nodded, laughed, pretended. But inside, my resolve hardened like steel.

Because while they were planning for next Friday, I was already planning my exit.

By Monday, the moving truck would be gone. By Tuesday, I’d be in Colorado, starting a new life they couldn’t control.

Let them wait at that bank, their perfect scheme crumbling. Let them realize, too late, that I was done being their backup plan.

As I drove home that night, the streetlights blurred through my windshield. For the first time in decades, I didn’t feel like a powerless daughter begging for scraps of love. I felt like someone standing on the edge of freedom, ready to leap.

And I couldn’t wait to watch their faces when they finally understood.

The Escape

The morning of the move came faster than I expected.

At eight a.m., the moving truck rumbled down my street, the diesel engine echoing between the buildings like a drumroll announcing freedom. The movers, two guys in blue shirts with sweat already soaking the collars, carried my boxes down the stairs while I hovered, nerves crackling. Each taped-up box felt like a piece of my old life being lifted out of me.

By noon, my apartment was stripped bare. The walls looked naked, the floor scuffed where my couch used to sit. I handed the keys to my landlord with a polite smile. “Heading to Colorado,” I explained vaguely. He wished me luck, then shut the door without a second glance.

That night, I stayed in a hotel near the airport. A temporary space, a waystation between the life I’d endured and the one waiting for me. I ordered cheap takeout, ate cross-legged on the bed, and stared at my phone lighting up with missed calls.

Mom. Dad. Isabella.

The notifications stacked higher and higher, voicemails piling up like angry debris. I silenced the device, set it face down on the nightstand, and let myself breathe.

Tuesday morning, I boarded a plane to Denver.

As the aircraft lifted from the runway, I looked down at the shrinking city—the beige houses, the cracked sidewalks, the heavy weight of years I was finally leaving behind. My old life disappeared into the clouds. For the first time, the thought of the future didn’t terrify me. It thrilled me.

Colorado was different in every way.

The air was thinner, sharper, like it was meant to wake you up. Mountains loomed on the horizon, jagged and unapologetic. The company put me up in a temporary apartment—sleek, modern, furnished better than anything I’d ever lived in. My new coworkers welcomed me like I was a missing puzzle piece. We ate lunch together at food trucks, swapped jokes over coffee, and treated me like a peer, not a disappointment.

The first night in my new place, I stood at the window and watched the sun sink behind the Rockies, painting the sky in wild shades of orange and purple. My chest tightened, not with fear this time, but with something close to joy.

I was free.

Friday came.

At exactly ten a.m., my phone started buzzing. First Mom. Then Dad. Then Isabella. Over and over, the calls stacked, vibrating against the desk where I’d set it. I ignored them.

At noon, the texts began.

Mom: Where are you? Everyone is here waiting.

Mom: Julia, call us back immediately.

Dad: You’re making us look like idiots. The banker is here.

Isabella: OMG Julia are you seriously doing this to me???

I muted the notifications and went to lunch with my new team, laughing over tacos while my phone lay face down, buzzing itself into a frenzy.

Finally, at one o’clock, I answered.

“WHERE are you?” Mom shrieked the second I picked up. Her voice was sharp enough to draw stares from my coworkers at the next table. “We’re all here waiting!”

I took a slow sip of my soda before replying. “Oh, that. I changed my mind. I’m not paying for Isabella’s apartment.”

The silence on the line lasted a beat, and then Mom exploded. “Julia, you can’t do this to us!”

“Actually,” I said evenly, “I can. And I just did.”

“I’m coming to your apartment right now and dragging you to this bank myself!”

That made me laugh out loud, the sound startling even to me. “Good luck with that, Mom. I moved to Colorado.”

Silence again, this time longer, heavier. Then the fury returned, hotter than before. “You can’t just abandon your family! We NEED you!”

“No,” I corrected, my voice steadier than it had ever been with her. “You need my money. That’s different.”

“That’s not true!” she snapped. “We’ve always cared about you!”

I actually laughed. “Right. That’s why you missed my graduation to take Isabella on vacation. That’s why you refused to help with my tuition but took out a second mortgage for hers. That’s why you’ve never once called me just to ask how I’m doing.”

Her voice faltered. “Julia, please—”

“I’m done,” I cut in firmly. “Don’t call me again.”

And I hung up.

The next few days were a storm of attempts—blocked numbers calling, emails with subject lines like Family comes first! and Don’t do this to your sister! I ignored every single one.

Finally, Francis called.

“How are you settling in, sweetheart?” she asked, her voice warm and steady as always.

“I’m good, Grandma,” I said, smiling despite the tension. “Really good.”

She sighed. “Your parents came to see me yesterday. They wanted me to convince you to come back and help Isabella. I told them this was their own fault—that they ignored you for years, refused to help you when you needed it, and then expected you to hand over hundreds of thousands of dollars like it was nothing. I told them they were delusional.”

“Good for you, Grandma,” I said, tears pricking my eyes.

“They didn’t like that very much,” she chuckled. “Your father even had the nerve to tell me I should cut off contact with you. I kicked them out. Told them not to come back until they were ready to apologize.”

I laughed through my tears. “You’re the only one who ever had my back.”

“And I always will,” she said firmly.

Six months later, Colorado felt like home. I loved my job. I had friends who actually wanted me around. I was saving for a down payment on my own house. Francis visited every few months, and we talked on the phone every week.

She told me Isabella never got the apartment. She was still renting some generic place, whining about how unfair it all was. My parents were still angry, but Francis didn’t care. “Let them stew,” she said. “They’ve made their bed.”

And me? I didn’t miss my old life at all. For the first time, I was living for myself, not for scraps of approval from people who never valued me.

Sometimes the bravest thing you’ll ever do is simply walk away.

The New Beginning

Six months into Colorado life, I barely recognized myself anymore—and I meant that in the best possible way.

My mornings began with sunlight spilling over the Rockies, turning the peaks into fire-tipped monuments. On weekends, I hiked with coworkers who quickly became friends, our laughter bouncing between the pines. I even bought a secondhand bike and rode it through the city streets, feeling a freedom I hadn’t known since childhood.

Work was thriving. Marcus, my boss, kept giving me bigger projects, the kind that came with visibility and respect. For once, I wasn’t just the girl who worked quietly in the background—I was the one people turned to when things got complicated.

But the best part? For the first time, my life was mine.

Francis called every Sunday evening, her voice crackling through the line but still warm as ever.

“How are you settling in, sweetheart?” she’d ask, and I’d tell her about hikes, projects, new recipes I’d tried (and occasionally burned).

She’d chuckle. “You sound happy.”

“I am,” I’d admit, surprised every time at how true it felt.

She visited in the spring, arriving with her little floral suitcase and a cardigan buttoned all the way up. I met her at the airport, and when she saw me waiting, she spread her arms wide, tears glinting in her eyes.

“Oh, my girl,” she whispered as we hugged. “You look lighter.”

We spent the week exploring farmers’ markets, strolling through mountain towns, eating far too much pie. One evening, sitting on my balcony with tea steaming in our cups, she sighed.

“You know,” she said, “my lease ends next year. I’ve been thinking… maybe I’ll move closer to you.”

My chest tightened with joy. “Grandma, I’d love that. We could see each other all the time.”

Her eyes twinkled. “We’ll see. But it’s nice to think about.”

Meanwhile, back home, my parents’ attempts to reach me dwindled into silence. At first they’d tried everything—calls from blocked numbers, guilt-laden emails, even letters that arrived at my Colorado address like ghosts from another life. I ignored them all.

Eventually, the noise stopped.

Francis updated me occasionally, though she always kept it short. “They’re still angry,” she’d say with a shrug. “Let them be.” She told me Isabella was still renting, still waiting for someone else to hand her the life she thought she deserved. The $350K dream apartment never materialized.

Each time I heard it, I felt lighter. Their schemes had lost their power over me.

One night, nearly a year after my move, I stood in my new apartment—bigger than the old one, with tall windows and a view of the mountains. I’d just gotten off the phone with Francis, who had promised to visit again in the summer.

I looked around the space I’d built—furniture I’d chosen, books stacked neatly on the shelves, photos of hikes and new friends pinned to the fridge. For the first time, the walls didn’t feel temporary.

I thought about the girl I’d been: the one who begged her parents to care, who starved herself of sleep and joy to pay off debts, who waited at graduations for people who never showed.

She was gone.

In her place stood someone stronger. Someone who knew her worth didn’t depend on people who refused to see it. Someone who had learned the hardest, bravest truth: sometimes family isn’t who raises you—it’s who shows up.

For me, that had always been Francis.

I raised my glass of wine that night, alone but not lonely, and whispered to the mountains beyond my window: “I’m free.”

Because I was.

And I always would be.

✅ The End

News

My Husband’s Mistress Moved Into Our House—So I Moved Them Both Into Bankruptcy… CH2

The Morning That Changed Everything It started on a gray Seattle morning, the kind where the air feels wet before…

My Stepfather Beat Me At The Hospital—But He Didn’t Notice Who Was Watching From The Bed… CH2

The Slap You Could Hear Through a Curtain The first time I accused Carl of stealing from my mother, my…

I Was Battling Cancer When My Wife Slept With My Best Friend; It Was the Beginning of Their End CH2

Valentine’s Day, or How to Kill a Man Quietly The thing about dying is that it makes everyone else unbearably…

I Found My Daughter In A Dog Kennel. I Made One Call, Now My Wife’s Boyfriend Is Gone CH2

The Kennel I’ve had nights in the desert where the wind cuts like wire, where the horizon shakes with heat…

Mom Slapped Me For Not Funding Brother’s Divorce—The Recording Went Straight To Five Judges… CH2

The Breaking Point I used to think financial abuse only happened in the headlines. To strangers. To people who didn’t…

My Sister VICIOUSLY Attacked Me And Tried To Steal My Fiancé. Now, My Parents DEMAND I Forgive Her. CH2

Part One: The Afternoon That Broke On the drive over, the sky had that Texas-blue that makes you think nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load