Part I

Kurt Kaminsky slammed the truck door so hard the cab rattled like an old soda machine coughing up change. He stood in the rust-blond light of evening and stared at the one-story house that had never kept its promises—stucco scabbed in patches, the porch sagging into a frown, a rectangle of lawn he’d refused to water all summer now crackled brown and brittle as burned toast. Fourteen years under that roof, and all it had sheltered lately was the sound of two people learning new ways to hate.

“Get in here already,” Jenna barked from the doorway, her figure a narrow slice against the glow. “It’s almost dinner. I’m not cooking extra if you’re skulking like a stray dog.”

Kurt felt the old gear engage—the one that turned his jaw into a vise and his voice into a weapon. He took two stiff steps toward her, rehearsing a sneer he’d worn smooth over the years, but something caught in him, like a bad tooth. He brushed past her without a word, keeping his eyes on the floorboards because he had learned the hard way that looking at Jenna and not saying anything was somehow worse than saying the wrong thing.

“Kurt, you’re tracking mud,” she hissed at his back. “Same argument every time.”

“Don’t start,” he said, not turning. “I’ve had a long day.”

“You always have a long day. And then you dump your attitude on me. You want me to greet you with a smile, give me a reason.”

They locked in the doorway to the kitchen like two rams on a mountain—breath tight, eyes glassed. Jenna’s bleached hair, pinned back in a hurry last week, showed a defiant stripe of dark at the roots. The condescension in her eyes could have polished stainless steel. His shoulders, pumped up by pride and a lifetime of lifting cars on jacks, bulged in a sweat-stained button-up that had never fit right and never would.

He broke first. He always did when Carrie was within earshot.

Their daughter sat at the table, phone face-up beside the plate, earbuds half in as if she wanted the option to hear and not hear them simultaneously. Thirteen—a concrete age poured in equal parts sarcasm and uncertainty—she glanced up with eyes so hollow with practiced boredom they made Kurt angrier than any insult.

“Dad’s home,” she muttered, rolling her eyes so hard it looked like effort. “We can all pretend to be happy now.”

“Don’t you have homework, kid?” Kurt said, too quickly, using the word to swat away the sting.

“I’ve got it under control,” she said, thumbs flicking a phantom message. “I’ll do it later.”

Jenna circled the table and yanked out a chair, the legs scraping a sound that had always set Kurt’s teeth on edge. “I’m not dealing with you both rolling your eyes all night,” she said. “Sit down, Kurt.”

He hovered, palms on the chair back. The casserole on the table oozed a red-orange sludge around pasta that had given up. He could smell the char under the sauce. He could smell the day on himself. “Headache,” he said, which was true. “I’m not hungry.”

“Always an excuse,” Jenna said flat. “Fine. Suit yourself. Carrie, eat before it congeals.”

Carrie pushed noodles around without enthusiasm. Kurt turned on his heel and drifted back into the living room, letting the bitter music of their muttering fill in behind him. He snatched his keys from the bowl by the couch.

“You’re leaving again?” Jenna called, the contempt baked to a crisp. “Why’d you bother coming home if you’re just going to slink off somewhere?”

“I need to clear my head,” he said, and stepped into the hardening light.

He stood in the yard and lit a cigarette. The first drag burned like an apology he owed his lungs. Smoke curled around his face and into his eyes, which was fine; he’d been making himself cry by accident for years.

He heard footsteps. Jenna leaned in the doorway, arms folded like a gate. “You want a divorce?” she asked, cold as old coins. “Because if you threaten to leave me, you better go through with it this time.”

“Why would I divorce you?” he said, sarcasm greasing the words. “We’re a picture-perfect family.”

“Don’t act like a victim,” she said. “You always do. You like stirring the pot. Then blaming everyone else when it boils over.”

“You make it easy,” he said, stepping closer so the smoke drifted into her face. “I go work all day at the lot, and I come home to your whining. That’s not a marriage. That’s a prison.”

“Prison?” She laughed without humor. “Look at this dump. I asked for a better house years ago, but you wouldn’t let go of a single penny. We could’ve upgraded, but no—had to hold on to your precious money. Funny you call it a prison. You’re the warden.”

Heat climbed his neck. He hated the house too. He’d bought it when he was still young enough to think flipping property was a personality. It had become, like too many things in his life, a symbol he wore like a weight. “You want a fancy place?” he said. “Go earn the down payment. Don’t expect me to pluck it from the air.”

“I do earn money,” she said. “All those hours at the bookstore. That’s not enough for you? God, you’re pathetic. A used car lot that’s barely afloat and you strut like some hot shot businessman.”

“Stop acting like you know my business,” he said, fists clenching. “I make enough to put food on the table when I feel like it.”

She shoved his shoulder. “Badge of honor? You do the bare minimum and expect applause.”

“Don’t touch me,” he snapped, batting her hand away. “The day you appreciate what I do is the day hell freezes over.”

“Fine,” she said, stepping back. “I’ll never appreciate a man who shows me nothing but scorn.”

He tossed his cigarette into the dead grass and crushed it under his boot with a little more force than necessary. “I’m done,” he said.

“Good riddance.”

The door slammed like a period at the end of a sentence they’d been writing for years. He got in the truck, turned the key, and let the engine’s familiar cough steady him. He didn’t look back.

The bar was the only one that still hung onto a neon sign the color of Gatorade. It buzzed in the humid dark like a cheap halo. The whiskey burned like he wanted it to. The second glass fell down his throat without him tasting it. Voices in the booth behind him snickered about bosses and wives and stupid luck. Someone told a Polish joke and the laughter went up in a cheap pop. His last name had always been a word people thought they could use to do a thing. He stared at his phone until the screen got greasy.

Carrie: Mom’s furious. She says you won’t come home. Is that true?

Kurt’s thumb hovered over the keyboard like it could type an entire explanation—how sometimes not coming home is the only way to keep from turning into a thing everyone would regret. He put the phone face-down and let the whiskey do the work instead.

He woke in a motel that had learned to stop pretending it was anything else. The room smelled like other people’s breath. His mouth tasted like old pennies. He had a voicemail from Anna at the lot, her voice practical with a soft edge he didn’t welcome: Boss, auction’s tomorrow. How many? Also George came by to check the transmissions—couldn’t find you. Everything okay?

He told her yes because that was easier than describing a house as a mouth full of broken teeth. He told her he’d handle George.

George. Tall, oil-stained, with that grin like he didn’t understand shame the same way other people did. Kurt had known him long enough to remember when they were friends. Somewhere between then and now, every “buddy” out of George’s mouth had started to sound like a dare.

The lot sat on the corner of two streets that had stopped asking where they were going. A string of angle-parked sedans flashed “Like New!” signs in the windows like lies with exclamation points. The chain-link fence’s gate shrieked, because of course it did. Anna looked up from behind the glass and gave him that look—worried, then smoothed into professional in less than a second.

“Kurt,” she said, “you look like twenty-seven hours.”

“I’m fine,” he lied. “Auction cars—ten, you said?”

“Ten slated,” she said, flipping her clipboard. “If we snag the Civic and the F-150, that’s twelve. George can do full inspections by week’s end.”

“Let him have them by Monday,” Kurt said.

The door opened on the word, as if summoned. George strolled in with that rolling gait, wiping his hands on a rag that would never be clean again. “Heard you got into it with the old lady,” he said, tone too friendly. “Everything cool?”

“I’m not paying you to snoop,” Kurt said. “Focus on transmissions.”

George put his hands up like the air had asked to frisk him. “Just making conversation.”

Kurt’s jaw worked like it had chew in it. Anna eyeballed the interaction, a quiet ‘this is going to be a problem’ hovering in her posture. George let himself out with a swing of the door that said more than necessary.

Anna waited a beat. “Boss,” she said softly, “you sure you want to keep him on? He’s been pushing.”

“He’s the best in town,” Kurt said. “We don’t fire the best in town because he’s nosy.”

Anna didn’t argue, which was one of the reasons he trusted her. She managed the place with a no-nonsense grace that kept the bills paid and the customers just this side of suspicious.

He worked the rest of the day like work could be a solvent. The cars lined up under the gray sky and tried their best to look honest. He closed early and drove back to the house he hated.

Jenna didn’t look up from the TV when he came in. “So, you’re back?”

“Needed my things,” he said. “Didn’t say I was staying.”

“I don’t care if you stay or go,” she said, eyes still on whatever ugly argument reality TV was staging. “Just stop stomping around like a tantrum-throwing toddler.”

He stepped closer, kept his voice low. “I’m the reason you can pay the cable bill.”

“That’s the old story,” she said, finally flicking her eyes to him. “You wave money to feel big. Meanwhile you barely keep this dump running. You’re always one bad month away from collapse.”

“At least I have a job,” he said.

“A used car dealer,” she said, with a snort. “Real respectable. Don’t blame me if your daughter doesn’t want to brag about it.”

He stiffened. “Carrie said that?”

“She might have,” Jenna said. “Kids talk. You wouldn’t know—you never ask her anything that isn’t an order.”

Carrie stepped into the doorway with the weary posture of someone who had arrived at a war knowing there are no neutral corners. Earbuds in, mascara smudged the way it does when a thirteen-year-old learns that eyes can be weapons. “Mom,” she said. “Dad. Chill. Go to your room.”

“In your room,” Kurt snapped at her, pointing down the hall because pointing felt like control. She exhaled in a way that could have blown him across the yard, spun, and did as told. Jenna stepped into his space, the heat off her like a stovetop.

“Don’t talk to her like that,” she said. “She’s not a doormat.”

“I’m the one paying the mortgage,” he said. “My name on it, not yours.”

Her face went white with anger. “News flash—you walked out. You gave up your say.”

Something animal clawed up his spine. He grabbed her wrist and leaned in until his breath bounced off her cheek. “You watch yourself or you’ll be the one walking,” he said.

“Lay a finger on me and I call the cops,” she said, eyes bright and hard. “Sleep it off in county. See how you like it.”

He dropped her wrist like it had burned him. “You’re not worth it,” he said, sick at the voice coming out of his own mouth.

The week stretched like gum—thin, sticky, sweet only in old memory. He slept in the motel sometimes. He slept in his truck when the motel clerk looked at him like a problem. The lot filled and emptied, and he stood on the asphalt talking APR like none of it mattered and all of it did. He watched George more than he should have. He noticed the way Anna leaned away when George got too close to the counter. He noticed how George ended phone calls when Kurt walked into the garage.

One afternoon when the sun had finally decided to show up like it meant it, Kurt walked in from a burger joint with a bag that had soaked through with grease. George leaned on the office counter, grinning at something that wasn’t funny. Anna’s mouth was a thin line.

“George,” Kurt said. “You want something?”

“What’s it to you?” George drawled.

Kurt put the bag down with more force than strictly necessary. “Anna, you good?”

“Yes, boss,” she said, tone clipped. “George was just leaving.”

George saluted with two fingers and slid toward the garage. “Yes, sir.”

When he was gone, Anna leaned in. “He’s been asking about your home situation,” she murmured. “I told him it’s none of his business.”

Kurt cursed under his breath. “He’s a snake. Next time he asks, send him packing.”

Anna hesitated. “Just so you know—I overheard him on the phone earlier. Something about meeting someone for coffee and your wife’s name came up. I didn’t get details. Just heard him say, ‘All right, Jenna. I’ll see you soon.’ I didn’t realize they were…friends.”

A muscle jumped in Kurt’s cheek. “Thanks,” he said. “Let me handle it.”

The words echoed in his head all evening. Handle it. Like it was a lug nut he could torque down. Like the problem would hold.

He drove by the house after dark, the way a cat circles a yard that used to be his. The living room lamp threw a rectangle of light onto the lawn. Through the slit of the curtain he saw Jenna on the couch in yoga pants and a tank top, her posture postured. He was about to knock when headlights pulled into the driveway and washed the porch in a new color.

A battered pickup. George.

Kurt stepped into the shadows of the twisted shrub near the porch—some bush he’d killed twice now by ignoring it—and watched. Jenna opened the door before George even knocked, pulling her hair into a messy bundle with one hand. George stepped in like he had a key.

Kurt’s jaw ached. The two of them moved like a conversation he didn’t have the script for. Jenna folded her arms and frowned. George talked with his hands, apologetic or selling—two gestures that look the same at the beginning. They sat. George scooted closer. Jenna rubbed her temples, then reached out and touched his arm—the kind of touch you give someone you trust to hear you. He put a hand on her back, a gentle little circle. She didn’t shake it off.

Rage tightened Kurt’s vision. He had to remind himself to breathe like he wasn’t drinking air through a straw. The scene shifted; Jenna rolled her eyes, stood, stalked down the hallway that led to the bedrooms. George followed.

Could they be—

He didn’t finish the thought. He retreated to his truck with a deliberate steadiness. He turned the key and pulled away from the curb so carefully it felt like a mockery of every other time he’d driven angry. He didn’t go back to the bar. He drove out beyond the strip malls, past the last traffic light the town could afford, and let the road unspool until his mind ran out of violent pictures.

Somewhere inside the noise a different suspicion tried to be heard. George was a dog. Jenna was Jenna. But Carrie—

He slammed the brakes too hard in an empty lot behind a shuttered florist. He thought of his kid rolling her eyes and then calling him at midnight when she was scared, voice a child’s again, whispering that Mom was throwing things. He thought of the word Uncle the way it got applied to men like George, not because there was blood but because somebody wanted there to be trust. He thought of cars—Civics and Corollas and the way kids held the idea of a first car in their mouths like candy.

He squeezed the steering wheel until his knuckles taxed the skin for extra color. Then he put the truck back in gear and went home to the motel bed that smelled like other men’s mistakes.

Three nights later, the phone exploded on the nightstand.

“Dad?” Carrie’s voice, high and cracked. “Mom’s throwing stuff around. Screaming about the mortgage. She says you’re threatening to kick us out. George is here and they’re both calling you—” The last word scrambled in static. “I’m scared.”

“Don’t open your door,” he said, already yanking on jeans that had learned to sleep on the chair. “I’m coming.”

The house was a lighthouse, every window blazing, a signal of trouble not comfort. The front door gave under his key in that way that meant Jenna had forgotten to throw the deadbolt again. The place smelled like a party that had given up. Jenna stood in the center of the living room like someone who had found the exact center of a storm and decided to own it. A wine bottle dangled from her hand like punctuation. George paced in the hallway mouth of the house like a bouncer at a bad club.

“You bastard,” Jenna said, pointing the bottle like a wand that could only do one trick. “You sneak in here like you own the place.”

“I do own it,” he said, and even to his own ears he sounded like a jerk. “Put the bottle down.”

“Don’t bark at her,” George said, stepping forward. “You left. You walked.”

“Family?” Kurt sneered. “She’s no family of mine if she’s—”

“How dare you,” Jenna spat. “Even if it were true, you abandoned us.”

He opened his mouth to say something unforgivable and saw, out of the corner of his vision, Carrie in the hallway in her oldest T-shirt, phone clutched, eyes wide enough you could see the child swimming behind the teenager trying to look tough.

“I’m sick of this,” she said, voice small-big. “Mom, Dad, end it. It’s obvious you hate each other. So do something.”

“Don’t you talk like that,” Jenna snapped. “He’s the villain here. Not me.”

“You’re both worthless,” Kurt hissed, the poison hitting the air before he could stop it. “Should’ve left years ago. You’re an arrogant— and Carrie’s turning out no better.”

“Dad,” Carrie said, shock and hurt in the one syllable like a lifetime of bitten lips. “Shut up.”

He flinched, regret pushing up for half a beat before anger shoved it under. George lunged. Fists. Elbow. A scuffle that felt like two high-school boys in grown-up bodies replaying a fight they’d lost years ago. Jenna shrieked. The wine bottle hit the carpet and sloshed a stain that looked like a wound.

“Carrie!” Kurt yelled, as if she belonged to him by volume.

“I’m here,” she said, crying quietly. “Please stop.”

He grabbed a stack of mail because his hand always reached for paper when he didn’t know what else to control. Mortgage statements. Receipts. Proof of one kind of manliness he knew how to make. He found what he wanted: the balance. Almost paid off. Leverage. The word tasted like pennies too.

“Perfect,” he muttered. “Now I can finalize the sale and cut you out.”

“You wouldn’t dare,” Jenna said. “This is my home.”

“You wanted a better place,” he snapped. “Find one. I’m done paying.”

Jenna grabbed his jacket. They locked eyes, both of them breathing like runners. “You can’t keep threatening me,” she said. “You’re a monster but you’re not invincible.”

“Watch me,” he said, and tore free.

He slept like a man who had accomplished something.

The week that followed was a blur of deeds and signatures and the kind of conversations men have with men about women that make the air worse. A friend-of-a-friend put him in touch with a lawyer whose office smelled like dust and bad advice. Paperwork appeared as if conjured. Kurt sold the lot to a shell whose articles of incorporation listed an address in a state he’d never been to. The bank didn’t so much nod as refuse to frown. He told himself it was smart. He told himself Jenna would never find the edges of the game.

One evening he unlocked the door to a cheap apartment that had at least the virtue of being entirely his and stepped into a small, square quiet. He might have enjoyed it if the footsteps in the hallway hadn’t been in someone else’s rhythm.

“How’d you find me?” he snapped when Jenna appeared, hair undone, eyes lit with a fire you can only carry for so long before it burns you too.

“I’m not an idiot,” she said. “I asked around.”

He wedged an arm against the doorframe when she tried to push past. “Get lost.”

“I need money,” she said, voice tight. “For me and Carrie. You selling the business, listing the house—you’re leaving us with nothing.”

He laughed, ugly. “You got your buddy George. Let him pay your bills.”

“He’s broke, you bastard,” she said, shoving him with a desperation that had nothing to do with romance and everything to do with survival. “This is your fault.”

“Stop blaming me for your choices,” he said. “You love me most when I’m a wallet.”

She tried to lunge again. He blocked. Her wrist in his hand felt like trespass and ownership both. He pushed her, not hard, but harder than he should have, and she stumbled against the corridor wall, eyes flaring and then flattening like she’d shelved something she’d come to say.

“You’ll regret this,” she said, voice trembling.

“No,” he said. “I won’t.”

She left with her shoulders squared like a soldier who has learned how to retreat without surrendering.

He shut the door, leaned his forehead against the cheap wood, and told himself he was unstoppable.

He believed it long enough to turn on the TV. Long enough to pour a drink he pretended was victory.

Long enough not to hear the house on the other side of town whispering to his daughter in a voice that wasn’t his.

It was three days later when he heard it himself.

He’d gone for the mail he’d pretended to ignore. He stood in the shrubs again, the cheap little spy who had slowly made spying his job, and peered through the slit in the curtain because he couldn’t not.

Jenna’s voice, a whisper like fabric scuffing on tile: “If you want Uncle Stevie to buy you a new car—”

The rest of the sentence slid under the clatter of a dish in the sink, under the pulse he could hear in his own neck, under the sudden and complete silence that falls when a choice offers itself like a hand.

He didn’t know whether he wanted to break the window or run.

He did neither.

He stood very still in his own dead garden and realized, with the slow horror of a man watching a train approach, that there are a hundred ways to lose a family. He had been practicing all of them.

Part II — The Whisper and the Wrecking Bar

He didn’t sleep that night. He sat on the edge of the motel bed staring at a TV that sold knives at two in the morning, and he held the sentence in his mouth like a nail.

If you want Uncle Stevie to buy you a new car—

He said it aloud once in the empty room, to hear how stupid it sounded, how cheap. He tried to swap variables: Uncle for your mom’s brother, new for fresh coat of paint on something that used to be on fire. It didn’t make it better. It made it worse.

By nine a.m. he’d wrapped the excuse of work around himself like armor and headed to the lot. The sky was washed and colorless, and the flag by the service bay snapped like it was trying to get someone’s attention. Anna was at her desk, hair in its tight bun like a dare to the day.

“You look like you wrestled the night and the night won,” she said.

“Who’s Uncle Stevie?” he asked.

Her face did that thing where a woman’s eyes flick to a point just left of the man she’s talking to because she’s loading words carefully. “Jenna’s half-brother,” she said. “Steven Krawiec. Runs Krawiec Auto Salvage out on County Line. He’s… flashy.”

“Shady,” Kurt said.

“He shows up at charity auctions with a checkbook,” she said. “Buys raffle baskets nobody wants and takes selfies with the principal. People call him generous because he’s loud about it.”

“Does he buy ‘new cars’ for thirteen-year-olds?” Kurt asked, voice flat. He could hear the skeptic in it, the mechanic, the man who had watched too many bent frames get Bondo’d into acting like bones.

“He lines up salvage titles, flips them,” Anna said carefully. “Paint, a VIN that checks out from a distance, and a buyer who wants to believe. I don’t know about thirteen-year-olds.”

Kurt looked toward the shop bay. George wasn’t in yet. The concrete floor was clean in a way that said someone wanted to impress him. He didn’t feel impressed.

“Boss,” Anna said, softer, “don’t go nuclear without facts.”

He nodded because he knew that sentence in his bones and had ignored it so many times he could have stitched it onto a patch. “If he puts my kid in a car that crumples like a beer can,” he said, “I will—”

“You will file for an injunction,” Anna said. “You will not go to County Line with a tire iron.”

He didn’t argue. He went to County Line with his hands empty.

Krawiec Auto Salvage looked exactly like its name: a rectangle of chain-link trying to hold back a tide of crumpled metal, a cinderblock office with a plastic plant in the window, a hand-painted sign that had been corrected three times because the vowels kept sliding off. The yard was a museum of bad days—bumpers with stories, windshields still stippled with spiderwebs.

A kid in a hoodie sat on a milk crate by the office door flipping a socket on and off a ratchet, bored. “You need a part?” he asked without standing.

“I need Stevie,” Kurt said.

The kid jerked his chin toward the far shed. “He’s around back. He don’t come out for everybody.”

“He’ll come out for me,” Kurt said, and he said it the way he used to say “sir” to his father—slightly sarcastic, mostly habit.

He found Stevie behind the shed with a cordless drill in his hand and a cigarette tucked into his bottom lip like punctuation. He was younger than Kurt by three years and had made up for it with a tan that came out of a bottle and a watch the size of a hockey puck. He was working on the back quarter panel of a late-model Corolla that had no business being alive. The panel didn’t quite meet the door. It was the kind of half-inch that gets people killed.

“Well, well,” Stevie said, grinning without warmth when he saw Kurt. “If it isn’t Mr. APR.”

“Don’t call me that,” Kurt said.

“Then what can I do you for, Mr. Almost-Ex-Brother-in-Law?” Stevie asked. He squeezed the drill trigger in a way that made the bit whine. “You want to buy something shiny? We got deals of the century.”

“That for Carrie?” Kurt asked, nodding at the Corolla. “You promising my kid a ‘new car’?”

Stevie rocked back on his heels. “I promised nothing,” he said. “I mentioned the word ‘birthday’ and ‘future’ in the same sentence in a house where the man who allegedly provides cannot be relied upon. Kids get excited.”

“She’s thirteen,” Kurt said.

“Kids get excited earlier,” Stevie said. “You’re welcome that someone’s teaching her to be excited about something that actually moves forward.”

Kurt looked at the weld line, the way the metal had been stitched where it had once split. Slick job, to an untrained eye. To him it looked like a promise that didn’t mean it. He felt heat rise from the base of his neck in the way it did when a salesman tried to pass off a flood car by spraying the vents with new car smell.

“You put my daughter in a stitched-together coffin, I will—”

“File an injunction?” Stevie said, mimicking Anna’s cadence with surprising accuracy. “Or come down here flapping your arms? Jenna says you’re very busy lawyering up and laundering your assets.”

“Jenna’s drunk,” Kurt shot back, even as a part of him winced at the truth that sat too close to that sentence.

Stevie’s grin sharpened. “She’s sober enough to read what certified mail says,” he said. “And sober enough to tell me you’re trying to sell the roof from over your kid’s head out of spite.”

Kurt stepped closer. “My name’s on that roof,” he said.

“Not for long,” Stevie said. “You forget what business I’m in? Titles. Chains of them. Paper can be made to tell the truth you want it to tell—if you know where to push.”

Kurt had known this man a long time. He had seen him slick-talk a county clerk into “finding” a tag that had never existed. He had watched him buy a smashed Honda at a police auction and sell it a month later to a contractor who drove it to a job site and never came home. He had not forgotten any of it.

“You stay away from my kid,” Kurt said. The sentence came out before he could season it. “You stay away from my house.”

Stevie looked down at the quarter panel and then up at Kurt. His eyes were a bright, false blue. “Not your house,” he said. “Not your kid, not the way you live. You walked. We remember that when men like you forget it.”

“You call me a man like me one more time—”

“What,” Stevie said, stepping in until Kurt could smell the sweet, rotten fruit of his cigarette. “You’ll do violence? Right here, in my yard, with my cameras? I don’t think so.”

The moment held like a door that knows it will slam and is just enjoying the anticipation. Kurt saw himself the way he imagined Anna saw him: fists swelling, jaw clamping, a man who mistook force for an argument. He stepped back. It felt like pulling a nail out of his own hand.

“I see that car anywhere near my daughter,” he said, “I’ll make sure the state knows which salvaged VINs got clean on County Line.”

“Good luck,” Stevie said. “The state has terrible hearing when its palm is full.”

Kurt turned away before he did something that would hire a lawyer for his enemies and a priest for his mother.

As he walked back to the truck, he saw the hoodie kid again, the socket now spinning on the ratchet like a little planet. “You got a sister?” Kurt asked.

The kid looked up, surprised. “Yeah.”

“You like her?”

The kid shrugged, teen reflex. “Mostly.”

“Keep her away from men who talk like they’re doing her a favor,” Kurt said.

The kid’s mouth did a quick uncertain tilt. “You too,” he said.

He left County Line and drove without thinking toward the school, because even a man who has given up on a house sometimes wants to pretend he remembers where safety used to be stored. It was lunch hour. The soccer field was empty except for a dog that had figured out how to get off its leash. He parked across the street, texted Carrie three words—You okay, kid?—and put his head back against the seat.

She didn’t answer.

He was halfway through the drive back to the lot when the phone rang. Not a teenager’s quick, impatient ping. A grown man’s ring.

“Kurt,” George said. “You busy?”

“What do you want?”

“Touchy,” George said. “I was at the house last night—Jenna had a leak—”

“Did you fix it with your hands or with your mouth?” Kurt said.

George laughed once, and it sounded wrong. “Stevie stopped by,” he said. “He said you were threatening to make trouble at the salvage yard. Just a heads-up. He doesn’t scare easy.”

“I don’t either,” Kurt said.

“You’re scared of losing,” George said, and hung up.

By the time Kurt walked into the office, Anna had her elbows on her desk and her head in her hands in a way he had never seen. She looked up, pushed her hair back, and said, “You got served.”

He stared at the envelope. It was heavy stock—the kind of paper lawyers use when they want you to feel the weight. He slid a finger under the flap.

Temporary restraining order. From Jenna. Words that read like a spell: harassment, threats, domestic disturbance, risk to minor. Stevie’s name showed up in the affidavit as a “concerned family member.” George’s name appeared as “corroborating witness.”

“She filed this?” he asked, somewhere between disbelief and the dull acceptance of a man who has been expecting rain and feels water on his face.

“She filed something,” Anna said. “A lawyer filed it. Jenna signed it.”

He put the paper down carefully, like if he creased it wrong it would explode. “I grabbed her wrist,” he said. “I did that.”

Anna didn’t say I know. She didn’t say I told you. She said, “Do you want a good lawyer or a loud one?”

“Good,” he said. “One who can read the parts where I’m wrong and not flinch.”

She nodded. “I’ll call Benson,” she said. “He’s expensive. He also tells the truth, even when people don’t like it.”

“Fine,” Kurt said. He rubbed his eyes with the heels of his hands. “I feel like my face is made of sandpaper.”

“Drink water,” she said. “And stop thinking you can fix this with your shoulders.”

He was about to tell her he didn’t know what that meant when the front door chimed. Carrie stood there in her school hoodie and a ripped backpack, hair in a messy bun that had lost the argument with gravity. She looked younger in the fluorescent light than he’d ever admit to her. She had a hard set to her mouth that he recognized: his own, on a smaller face.

“Hey,” he said, too brightly.

“Can I sit?” she asked, like it was an office she didn’t belong in.

Anna stood up so fast her chair skittered. “You can have my chair,” she said, and slid out of it, retreating to the back with a quick, professional, kind exit.

Carrie perched. She didn’t put her phone down. She looked at it, like a talisman, then up at him. “Mom’s telling people you’re making us homeless,” she said.

“I sent notice,” he said slowly. “We talked about it in that living room you hate. That house is a mouthful of broken glass. It…we were drowning.”

“You don’t drown on carpet,” she said, and he would have laughed if it didn’t hurt.

“Stevie,” he said, unable to keep the acid out of the name.

“Uncle Stevie said if you don’t come to your senses, he’ll make sure we have wheels,” she said, chin up in that way that said she wanted to be proud but was afraid she was borrowing pride with interest. “He said I could pick the color.”

“Color,” he said. The word broke in the middle. “Color doesn’t keep a roof from folding.”

Her eyes flashed. “I don’t know what that means,” she said. “I just know him and Mom say you’re punishing us.”

“I’m trying—” he started, and then stopped, because he had no sentence that didn’t indict him. “I don’t want you in one of his cars.”

“You hate him,” she said.

“He sells chrome on coffins,” he said. “I know the weld when I see it.”

She swallowed. She squared her shoulders the way she had when she was six and learning to stay on a bike: bravado as flotation device. “You can hate him,” she said. “But you don’t get to hate me for talking to him.”

“I don’t,” he said too quickly.

“You called me worthless,” she said. She didn’t make it a question.

“I—” He tried to grab the words back from the air. He saw them, the exact shape of them, and wanted to be a different man than the one who had said them. “I was wrong.”

She looked down at her phone. Her thumb hovered. “I don’t need you to be perfect,” she said, and it sounded like a script she had been given to make a hard scene play better. “I need you to not be this.”

“What is ‘this’?”

“Mean,” she said. “Mean and loud and gone.”

He closed his eyes. When he opened them, she was already up, already halfway to the door, because teenagers are helicopters: landing only long enough to make you feel it.

“Carrie,” he said.

She turned.

“Don’t ride with Stevie,” he said. “Not because I’m mad. Because I’m scared.”

She made a face that looked like agreement and defiance glued together. “We’ll see,” she said, and slipped out.

Benson’s office was three floors up in a building that smelled like old paper and the kind of wood that gets polished more than it gets touched. Benson had a tie that someone liked and a pen that looked like it had written apologies for kings.

“You’ve done yourself no favors,” he said after reading the filing. “But you haven’t hung yourself either.”

“That’s…encouraging?”

“It’s true,” Benson said. “Truth is the only useful kind of encouraging. We’ll contest the order. We’ll offer to set a parenting plan that doesn’t require Carrie to be within earshot of a brawl. We will not sell the house out from under them with thirty days notice because a judge will see that as what it is.”

“Which is?”

“Vindictive,” Benson said. “You will structure the sale as part of the separation. You will let the court apportion equity. You will stop making calls from anonymous LLCs because opposing counsel has eyes.”

Kurt nodded. The paper felt like it had weight in his lap. “Stevie,” he said.

Benson lifted one eyebrow. “The salvage man? Keep him out of this courtroom by keeping yourself out of his yard. You can’t stop your wife’s brother from existing. You can stop giving him your temper like a gift.”

“What if he puts my kid in a death trap?”

“Then you show me the paperwork and the inspection,” Benson said. “You do not show me a video of you swinging a fist, because I will hand you to someone else to represent.”

He left the office with a list that felt like an instruction manual for a machine he had never owned: drink water, sleep, don’t text after ten, stop equating volume with love.

He made it forty-eight hours.

Saturday afternoon, the park smelled like wet dirt and hot plastic. The soccer field was a rectangle of parents pretending not to care as much as they did. Jenna stood near the goal in sunglasses and an attitude. Stevie leaned against a fence post in a shirt two buttons too low. Carrie ran midfield like she owned the grass.

Kurt kept to the far side, hands in his pockets, the restraint itself an exercise. He was doing it. He was not exploding.

That was when Stevie’s tow truck pulled up along the curb with a delivery behind it: a gleaming white Corolla, paint so fresh you could still smell the optimism. A big ribbon the color of a bad idea sat on the hood.

Carrie saw it and blazed with a light Kurt hadn’t seen on her in months. She glanced at him, then quickly away, like she couldn’t afford to fold. The game ended in a cluster of shin guards and red cheeks. Jenna swept her girl into a hug, then pointed toward the ribbon like she was presenting a game show prize.

Kurt crossed the field faster than he knew he could move. “No,” he said, voice barely more than breath. “No. Not like this.”

Carrie put a palm on the hood as if checking a forehead for fever. “Uncle Stevie says—”

“I don’t care what your uncle says,” Kurt said, and the sentence hit the air with more force than his mouth had measured.

“You don’t get to decide,” Jenna said, stepping in, sunglasses lowering to reveal the eyes that had undone him years ago. “You left.”

“Carrie,” he said, lowering himself so he wasn’t towering. “Let me get it inspected. If it passes—a real shop, not Stevie’s yard—then we’ll talk about it. If it doesn’t, he takes it back, and you get something that will not fold when a pickup looks at it angry.”

Stevie laughed, loud enough for half the field to hear. “You calling me crooked in front of witnesses?”

“I’m calling you what you are,” Kurt said.

Stevie took a step. Parents glanced. Someone pulled out a phone because that’s what you do when trouble is about to ask for screen time. Carrie looked between the men and looked exactly like what she was: a kid standing in the crossfire of two pride-wounded grown boys.

“Please,” she said. The word was so small and so heavy in the same breath that all three adults looked at her. “Please don’t do this here.”

Kurt took an inch of air into his lungs. He let it out slow, like a trick. “Fine,” he said. He looked at Stevie. “Inspection, Monday morning. My shop or Benson writes to the DMV.”

Stevie spread his hands. “Bring your magnifying glass,” he said. “We’ll pass.”

Jenna squeezed Carrie’s shoulder. She looked triumphant in a way that made Kurt want to lie down on the grass. “You see?” she murmured to their daughter. “I told you. If you want Uncle Stevie to buy you a new car… sometimes you have to let grown-ups work out their nonsense.”

It was the wrong lesson. It was exactly the lesson. Kurt walked away before the sentence could find his mouth that would ruin it all.

On Monday morning, the Corolla rolled up the shop driveway. George was there, too, leaning with his arms crossed like a man who had built the car with his hands and wanted to dare someone to say otherwise. Anna stood with a clipboard. Kurt met them with a set of keys and a calm he had borrowed from someplace he didn’t recognize.

“Up on the lift,” he said.

The car rose with a whine that sounded like someone complaining before they’ve been introduced to an actual problem. Kurt slid under. He ran his fingers along the welds. He looked at the crumple zones. He traced the seam where the rear clip had been married to a body that hadn’t asked for a spouse. He set his jaw.

He rolled out on the creeper and wiped his hands. Carrie stood ten feet away, wringing the strap of her bag. Jenna watched with folded arms. Stevie smirked in that way he had. George chewed gum like he wanted it to be someone’s face.

“Well?” Jenna said.

Kurt looked at his daughter. “I won’t sign off on this,” he said.

Stevie sneered. “Because you’re mad,” he said.

“Because the weld’s pretty but the geometry’s wrong,” Kurt said evenly. “You hit an offset barrier at forty and the back seat takes the kiss.”

Carrie blinked. She didn’t like science. She understood kisses. She stepped back from the car like it had whispered something gross.

Jenna’s mouth went tight. “He’s lying,” she said to Stevie, not taking her eyes off Kurt.

Stevie shrugged. “We can take it to my guy.”

“You take it to anyone you want,” Kurt said. “But if Carrie drives it, I go back to Benson and file for emergency relief on the grounds of safety. And the judge reads worse words than ‘vindictive.’”

Carrie looked small in her hoodie and her hope. “So I get nothing,” she said, and it was the precise twelve-year-old cruelty that had come installed in all of them—the one that cuts at the adult who tells the truth.

Kurt swallowed. “You get me,” he said. “And a car that will keep you alive long enough to hate me later.”

No one moved for a heartbeat. Then Anna cleared her throat. “I’ve got a line on a ‘12 Civic,” she said, eyes on Carrie. “Two owners, no record of marriage to a rear clip. If your dad approves, you can pick the color. That part is non-negotiable.”

Carrie’s mouth did the quick, disbelieving lift. “For real?”

“For real,” Anna said. “Within reason. No neon.”

“Neon is a birthright,” Carrie said, managing a smile. It changed Kurt in a place he hadn’t realized could still be moved.

Jenna pivoted toward Stevie like a general who can count casualties. He raised his hands, palms out. “Hey,” he said. “We tried.”

“Yeah,” she said. “We did.”

Kurt watched the ribbon on the hood list sideways in the morning breeze. He felt the urge to gloat, to stick it to Stevie, to say something that would salt the ground. He took a breath and didn’t.

When they were gone—Stevie towing his mistake back to County Line, Jenna walking fast with her jaw set, Carrie hanging back long enough to bump her shoulder lightly against his as if to say okay—Kurt sat on the shop step and let the adrenaline leak out his fingers.

“Benson called,” Anna said, handing him a bottled water. “Temporary hearing is set. We can get the restraining order modified. And if you don’t start sleeping, I’m going to put melatonin in your coffee.”

He laughed. It felt like an engine turning over after a winter you thought had killed it. “You’re good at this,” he said.

“I’m good at not letting grown men ruin themselves when there are children watching,” she said. “It’s my hobby.”

He leaned his head back and stared up at the strip of sky the bay door allowed. It was a blue that didn’t make promises it couldn’t keep. He sipped the water.

Across the street, a robin tugged a worm from a lawn that had decided to forgive April. Somewhere over County Line, a man with a bad idea took off his ribbon and pretended it had never been knotted. Inside the office, a phone rang with a problem that would insist on being solved. And in the space between one heartbeat and the next, Kurt understood that the difference between being a man who breaks things and a man who builds is often just one withheld sentence and one offered hand.

He stood. He had a hearing to prepare for, a daughter to drive to school, and a Civic to inspect like he was deciding whether to bless a spaceship headed for a planet he hadn’t visited in years.

“Color,” he murmured, and smiled in spite of himself. “We’ll let her pick the color.”

Part III

The courthouse wasn’t grand; it was tired. Fluorescent lights hummed like old bees, and the air smelled like paper that had been breathed on too many times. Kurt stood in the hallway outside Family Division and watched other people’s lives get carried past in manila folders. Men in polo shirts with their Sunday jawlines on. Women with purses that looked like mailbags. Two teenagers sharing one set of earbuds because even this kind of morning needed a soundtrack.

Anna pressed a Styrofoam cup of coffee into his hand and made the face that meant sip it for the ritual, not because it’s good. “Benson’s in with the clerk,” she said. “He’ll get us called sooner. Jenna’s counsel is—” She paused, choosing words like stepping stones over a river. “—not an idiot.”

He nodded. He felt like he was wearing the wrong skin. Sleep had finally found him the night before and then, stupidly, left in a hurry. He was surprised to realize he wasn’t angry. He was…alert. Like a man who had been fined points on his license and suddenly remembered to signal every turn.

Jenna arrived with a lawyer who wore a suit like it belonged to him and sunglasses like he wanted to keep a piece of himself private. Stevie didn’t come into the building; Kurt saw him in the slot of window at the end of the hall, leaning against his truck, sunglasses on, phone to his ear, an orbit of stink-eye around him from people who did not appreciate his perfume of swagger. George wasn’t there. The relief was weird and disappointing at the same time. Carrie came last, with a court-appointed social worker who stayed a half step behind her like a bodyguard and a friend. She wore her hoodie zipped to the throat and her hair in a bun she’d decided not to pretend was neat.

“Kaminsky vs. Kaminsky,” the clerk called, in a voice that made even names sound like citations.

The courtroom had a high blue seal on the wall and a clock that no one wanted to see. The judge—Shelton, Benson had said, seasoned by a thousand versions of this—looked like a woman who had read the book and then spent her career living in the footnotes. She eyed the gallery, the counsel tables, the parents, the child, and did what good judges do: established the weather.

“We are here on a temporary restraining order,” she said, “a proposed parenting plan, and a motion to enjoin the immediate sale of the family home. I have read the filings.” Her eyes went from one table to the other like a well-thrown ball. “I will hear from counsel.”

Jenna’s lawyer spoke first. He was smooth without slime. He painted a picture that made sense from his side of the canvas: a husband who left, a mother who was scared, a child who was learning to duck. He said threats softly and safety loudly. He said the word mortgage like it was a throat being squeezed.

Benson waited, because waiting was part of the service he provided. When he stood, he didn’t clear his throat the way fancy lawyers do; he simply began. “Your Honor, Mr. Kaminsky has not been his best self. He grabbed a wrist in a moment everyone in this room wishes had gone differently. He used words he cannot take back. He also did not break the law when he moved out, and he did not lose his right to due process when he decided to restructure his business. We are not asking this court to crown a hero. We are asking it to act in the best interest of a thirteen-year-old who deserves to live in a house where the adults’ fights are not the weather.”

Shelton nodded like she’d been waiting for someone to say that last part in exactly those words. “Mr. Kaminsky,” she said, and the way she said his name made him feel like roll call in fifth grade when you weren’t sure if the teacher knew your last assignment had been your mother’s handwriting. “Did you grab your wife’s wrist?”

“Yes,” he said, because lying would be fatal and because something in Benson’s jaw had communicated that this was the moment you do not perform.

“Are you threatening to sell the house and put them out on thirty days’ notice?”

“I sent notice,” he said. “I am willing to rescind and set a sale within the separation, with distribution of equity per court.”

Jenna had the decency not to gasp. Her lawyer shifted one inch, then shifted back.

“Do you have a plan for your daughter’s residence and visitation that does not require her to choose between which adult’s anger she prefers?” the judge asked.

“Yes,” he said. Benson slid the document forward like a magician’s deck, but the judge looked at Kurt as if the paper were less important than the man holding up the line. “I want primary residential time with a week-on, week-off schedule during the school year with midweek dinners. If—” he glanced at Carrie, who stared at a spot two inches above his shoulder with the focus of a sniper— “—if Carrie would feel safer beginning with a graduated plan, with daytime only for a month and then overnights, I can…we can do that.” The pronoun hurt in a good way. It sounded like a stone you set at the bottom of a wall and then build around.

“Ms. Kaminsky?” Shelton said, turning. “Do you understand that the house will not be sold out from under you with thirty days’ notice, but that it will be handled within these proceedings?”

“I understand,” Jenna said, and her voice had lost some of the brittle that had become her armor. “I am angry. But I understand.”

“Do you understand that the restraining order will be modified to prohibit harassment and for both of you to stay away from each other’s residences unless it is for child exchange—and that any violence going forward will trigger consequences neither of you can bargain with?”

Jenna nodded. “Yes.”

The judge looked at Carrie, not the way adults look at children when they want them to parrot an answer, but the way people look at witnesses. “Ms. Kaminsky,” she said, “do you feel safe?”

Carrie’s lip trembled in a way she would deny for years. “Sometimes,” she said.

“Do you feel safer with economic certainty?”

Carrie looked down at her shoes. They were scuffed; she’d always been hard on shoes. “Yes.”

“And do you understand,” the judge said gently, spiraling the conversation away from spectacle, “that grown-ups with their own problems can be both wrong and loving, and that my job is not to figure out who has the best adjectives but to keep the people in your house alive and housed?”

Carrie nodded. A single, small nod. The kind you give when you’ve just been handed a new way to think.

There was more—there is always more in these rooms. Service addresses. No-contact language that makes lawyers feel like they have hit all the squares on the card. A gentle suggestion from the bench that therapy is not a punishment but a tool. And then the gavel without the gavel, just the court officer’s, “All rise,” and the hum back out into the hallway where people carry their new paper like instructions for a machine they didn’t order but will now be responsible for.

Outside the courthouse, sunlight hit concrete and bounced back like an apology. Stevie had disappeared. Jenna stood with her lawyer, who spoke to her in a tone that suggested he told his own kids not to run near the pool. Benson shook Kurt’s hand. “That went as well as you deserved,” he said. “Better than you might have.”

“Thank you,” Kurt said, and he meant it with his whole sore face.

“Next,” Benson said, “you do the invisible work. It is less satisfying than a public victory. It is also where your daughter will decide who you are.”

Kurt nodded.

Anna appeared with a brown bag that said eat this. “You didn’t faint,” she said. “Good.”

Carrie hung back, as if tethered. The social worker pretended to check her phone and then took three careful steps away. Jenna exhaled and put her fingers to her eyes the way people do when they’re ashamed to cry and smart enough to know they shouldn’t be.

“Carrie,” Kurt said.

“Hey,” she said, offhand, that teenager flick.

“You want to pick a color?” he asked.

Her mouth twitched. “Neon.”

“Compromise,” he said. “Bright but not illegal.”

“Teal,” she said, like a test.

“We’ll see what’s on the lot,” he said. “We will not buy hope with a paint swatch.”

“Okay,” she said. She hesitated like a bird on a wire. “Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“That thing you said before. About me. Worthless.”

He winced. “I hate my mouth, sometimes.”

She nodded. Then, suddenly, with a swiftness that made every adult within earshot pretend they weren’t moved, she leaned two inches closer and bumped her shoulder against his again, as if to say you can keep trying. Then she followed the social worker down the steps, hair catching the sun.

He didn’t burn the shell corporation. He dissolved it, properly, with papers Benson reviewed and the Secretary of State acknowledged. He sat down with Anna in the back office of the lot and pushed a folder across the desk with his name on it and hers below.

“I can’t run this right,” he said, and she narrowed her eyes until he laughed. “I can run a lot of it. But you’ve been running all of it while I learned how not to be a moron. If you want the job title to match the work, be my partner. Real papers. We split. We hire a mechanic who doesn’t ask after my marriage during an oil change.”

She blinked and then did the thing she always did when she was pleased: made no big fuss. “Okay,” she said. “On two conditions.”

“Name them.”

“We close at six,” she said. “People need lives. That includes you. And we do Saturday clinics once a month for single moms who got sold junk on County Line. We teach them what a bad weld looks like.”

“Deal,” he said, and felt the odd lift in his chest that came when you recognized the shape of a good idea.

He posted a job listing that did not say, “No George.” It said, ASE certified, decent human, no drama. A man named Luis showed up with a toolbox that had been organized with care and a photo of two boys taped to the inside like a reminder. He worked three days and then came into the office and said, “Do you care if I take my lunch to the park and throw a ball?” Kurt said, “I care if you don’t.”

When George called two days later to see if there was “any work that didn’t involve ripping collars,” Kurt said, “We’re moving on.” It felt strange and good to not justify anything.

The DMV investigators didn’t need Benson’s letter. The state had terrible hearing when the palm was full; it had excellent hearing when several similar complaints hit the same desk in the same week. A woman whose husband had been T-boned in a “repaired” Sonata, a kid whose airbags deployed with the velocity of confetti, a mechanic who whispered into a hotline because he’d seen his name on a stack of inspection stickers he didn’t stick. When the van with the state crest pulled into County Line, Stevie posted about “harassment” on a social feed. The post got twenty-seven likes and then disappeared.

Kurt didn’t drive by. He didn’t need the spectacle. He had enough to do. He signed a parenting plan that spelled out holidays and homework. He set an alarm for Thursdays to text, You have that math test? How can I help? He stood in a counselor’s office and said, “I don’t know how to speak without breaking things.” The counselor was a woman with sleeves of tattoos and a voice that sounded like good coffee. She said, “We will teach your mouth to wait for your heart.”

He went to a group that met in the basement of a church and didn’t know where to put their hands. The men talked around their hurt like it was a dog they couldn’t name. He said, “I called my kid worthless,” and waited for the stoning that didn’t come. A man with a mustache and a wedding band tan line said, “We carry our fathers into the room and then we put them down,” and the room was quiet in the way rooms get when a sentence hits the nail without smashing the board.

He started watering the little strip of grass outside his apartment. It didn’t deserve it. He did it anyway.

The Civic was a ‘12 in gray—boring, reliable, without a car note or a history. Luis changed the belt, resealed a small leak, rotated tires. The test drive was nothing: all good families are boring up to a point. When they pulled back into the lot, Anna came out with a plastic ring of paint chips like a practical midnight. “If we’re doing this,” she said, “we’re doing it right.”

Carrie frowned at the options like a fashion editor. “That one,” she said, tapping a chip the color of the shallow end of a lake. “Teal-ish.”

“You realize this is vinyl wrap and not actual paint,” Kurt said. “It’s like a fancy sticker.”

“Fancy stickers are a birthright,” she said. “Besides, it’s reversible if I change my mind. Or you make me.”

They wrapped the mirrors and the spoiler and a neat line along the rocker panels. It looked just enough like something a kid would love and not enough like something that would embarrass her in front of the sophomores. When they rolled it into the sunlight, she made a noise that had not come out of her since she was nine.

“Rules,” Kurt said, and the word no longer tasted like iron. “Seatbelts. Stops full. Phones down. Friends who vape get dropped at a corner, not my driveway. You text when you get there and when you leave. And you don’t ride in anything Uncle Stevie ‘makes new’ without me putting it on a lift first.”

“Yes, Dad,” she said, and this time it was not a teen ugh but something else. Agreement. Affection. The beginning of trust as a practice, not a feeling.

Jenna came by to see it because she is still Carrie’s mother, and they are still a family even when geography and paper say otherwise. She ran her fingers along the teal like she was smoothing a crease out of the day. “It’s nice,” she said, and the words were small and true. She looked at Kurt and in her eyes was the smallest apology he’d ever seen; he pulled out the smallest one he had. It was enough for the driveway.

Later, when the apartment was quiet and the little patch of grass outside was trying its best despite July, Kurt stood at the sink and washed two plates. He could hear a TV in the apartment next door talking about a storm in another part of the country. He could smell motor oil lingering in his own skin because some things are permanent. He dried his hands and stared at his reflection in the window. He didn’t look unstoppable. Thank God.

His phone buzzed. A text from Benson: Final hearing set. We can finalize the sale as stipulated and allocate. You did the work. Keep doing it.

Another from Anna: Luis says bring your running shoes. Saturday after clinic we’re playing pickup. You’re goalie because you like stopping things.

And one from an unknown number that wasn’t unknown: House on County Line shut. DMV took plates. Tell your guy he was right. — LJ

The hoodie kid. He saved the contact. Let me know where you land, he typed, and hit send.

From Carrie, late but not so late that he had to hold his breath: Home from Sarah’s. Teal looks better under streetlights. Night.

Night, he wrote back. Proud of you. Then, because he was learning, he put the phone face down and went to bed with a book instead of whiskey.

They finalized in September. The leaves had the good sense to start turning only when they were ready. The hearing was quiet. The judge read the stipulation into the record. They sold the house to a teacher with a beard and a woman who wore sensible shoes and had a laugh like a porch light. Jenna took her share and found a duplex near the school with a tree in the front yard that would want lights come December. Kurt made the last payment on the Civic insurance with a check that didn’t bounce not because of luck but because he had planned for it.

George popped up at a different lot two towns over. Kurt wished him no harm and no luck. Stevie pled out to fines, training, and three years of a small gray box on his phone that would ensure he showed up where he said he’d be. He posted about persecution less and photos of his niece’s winter formal dress more. People are complicated. They don’t stop being related just because you want them to.

On a Saturday in October, Kurt stood on a length of chalked grass and watched a ball arc toward him because of course they’d stuck him in goal. Luis whooped somewhere to his left. Anna yelled, “Hands!” the way she yelled “Paperwork!” and he laughed, put his palms out, and took the sting of the shot. He fell backward in the grass and felt, for a second, like a kid who hadn’t yet learned to mistrust the ground.

He drove Carrie home in the Civic, teal flashing in the corners of his eyes like a dare. She told him a story about a teacher who wore mismatched socks on purpose. He told her a story about the first car he ever sold that didn’t deserve to be on the road and the way he still wakes at night sometimes thinking about it and the truck it met at an intersection. He didn’t pretend that telling made it okay. He didn’t pretend anything.

At a red light, she leaned her head against the window and said, “I like this car.”

“I like this driver,” he said.

“You still make me crazy,” she said, then grinned when the light turned green. “That’s not a challenge.”

“I’m learning,” he said.

They rolled through town with the windows down and the radio up because that is what you do when the weather and the day and the company give you permission. He didn’t notice until later that he had taken the long way, past the street where the house used to be, and that it didn’t take anything from him to see it. The porch had a new swing. The lawn looked like it forgave. A kid he didn’t know rode a bike with duct tape on the seat. Good. Let somebody else let it be a house instead of a mouthful of broken teeth.

At the light where they would turn toward Jenna’s duplex and the tree that was already trying on colors, Carrie cleared her throat. “Mom said she’s sorry she taught me to whisper for shortcuts,” she said. “She said sometimes grown-ups get tired and try to get a win the easy way.”

“We did,” he said. “We both did.”

“Uncle Stevie says—”

“Uncle Stevie will always have something to say,” Kurt said. He paused, then added, “Sometimes he’ll be right. Sometimes he won’t. You’ll learn to hear the difference. Listen for the weld under the paint.”

“It’s teal,” she said, smiling.

“Yeah,” he said, and the word was a whole paragraph. “It is.”

They turned. They headed home. Not to the same door, but to places that, finally, felt like shelter. The car hummed like a promise that wasn’t a lie. And for the first time in a long time, Kurt felt the difference between a man who breaks and a man who builds—not as a slogan he could say to impress a judge or a kid or a manager, but as a habit his hands could learn, one quiet, careful day at a time.

The End.

News

I walked to work in rain every day until grandpa said, how’s the car I bought you? I froze…. CH2

Part I The rain in our town never learned moderation. It either spit like a petulant child or poured like…

MY WEDDING DAY, MOTHER-IN-LAW SLANDERED, HUSBAND TAKES ACTION – BUT I RESPONDED IN AN UNEXPECTED WAY… CH2

Part I I was twenty-eight, wrapped in white satin and a dozen years of borrowed dreams, standing in a Denver…

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale… CH2

Part I: The Laugh Track If you’d asked me a year ago to describe my mother-in-law’s dining room, I would’ve…

When sister said she would inherit all of my dad’s estate, I accepted it. Because the inheritance is… CH2

Part I: I was seven the year my biological father vanished like a bad storm—loud, messy, gone by morning. My…

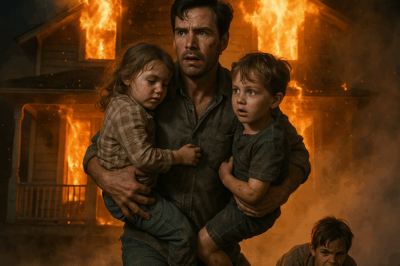

The house caught fire my stepdad carried his kids out — I crawled through the smoke & saved myself… CH2

Part I The smoke hit me first, thick and bitter, the kind that grabs your throat with a greasy hand….

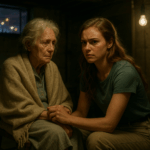

She Sat Alone at the Wedding Then a Stranger Said, Act Like You’re With Me… CH2

Part I: The wedding hall glowed like a snow globe come to life—chandeliers dripping golden light, laughter and clinking glasses…

End of content

No more pages to load