Part One — The Text

The merger contract blurred before my eyes at the exact second my phone buzzed.

Brooklyn: i think maybe we need to break up.

Five years of marriage reduced to a casual suggestion, sent while I sat under the cold breath of my law office’s air conditioning and reviewed a seven-figure acquisition like it was just another Tuesday. The hum in the vents became a tunnel of silence. My fingers went numb.

I watched the blinking cursor in our message thread like a flatline. Thirty seconds. Exactly thirty. Then I typed: I agree. Your stuff will be on the porch in an hour.

The three dots—their own brand of heartbeat—appeared, vanished, reappeared.

Brooklyn: wait i was joking. wtf ethan call me.

I didn’t call. I stood, closed the Caldwell v. Newford folder with a steady hand, shut down my monitor, and walked out of Conference B without a backward glance. I nodded to Angela at reception—“client call,” I lied—and took the elevator down, the mirror in the brushed-steel panel reflecting a man I recognized only because I’d shaved him that morning. Thirty-two years old, corporate attorney, decently tailored suit, face like a door someone had just slammed.

What Brooklyn didn’t know was that her “joke” had just tripped a wire I’d strung weeks ago. I wasn’t improvising. I had a plan.

Lincoln Park was the same as always: dog-walkers, strollers, a runner with neon shoes ticking down a pace only he cared about. I parked in the garage and walked into a house I had bought with cash from my bonus four months before our wedding and titled, very deliberately, to Ethan Caldwell, an unmarried man. Illinois doesn’t play games with premarital assets. My wife had never asked about the deed because paperwork bored her. She preferred the story of the house to the structure of it.

I went to our bedroom. Brooklyn kept her clothes color-coordinated, a mini department store curated by a woman who believed presentation was proof. I started pulling hangers, laying dresses in neat stacks on the bed, the way I organize discovery—methodical, precise, emotionless. Then garbage bags, thick ones from the garage, the kind contractors use. Her shoes fit like soldiers along the wall of the hallway for a moment and then disappeared into plastic. Perfume bottles, makeup kits, a jewelry travel case she never traveled with but liked to show to friends.

My phone lit up and lit up and lit up. Messages, calls, more messages. The screen, the world, the echo of the air conditioner—noise I used to mistake for calm.

For six nights straight she’d been “working late.” Either Brooklyn had discovered fusion or she’d discovered someone else’s cologne. Three weeks earlier, I hired Daniel Reed, a private investigator recommended by a client with a divorce so clean it should have been bottled and sold. Former Chicago PD, good at documentation and not easily spooked. I didn’t ask him to catch an affair. I asked him to verify or disprove a pattern.

He verified.

Photos: Brooklyn stepping through the revolving doors of the Palmer House Hilton on a Tuesday night with Garrett Whitfield, CEO of Whitfield Luxury Properties, chin angled like his own billboard. Married. Publicly. Successfully. To Sloane Whitfield—former federal prosecutor and daughter of appellate judge Harrison Blackwood. The pictures continued: a Gibson’s dinner, his hand grazing the small of her back; a phone log thick with late-night calls; a grainy parking lot shot of a Bentley behind a warehouse, windows tinted but the story not.

At 54 minutes in, I had the bags on the porch, the door propped with a paint can, the loop of a trash bag drawstring cinched around my wrist like a tourniquet. That was when Brooklyn’s BMW F30 slid into our driveway and braked too fast. She got out like the car was burning, blonde hair perfect because perfection is its own religion. She took in the bags, then me, and I watched surprise try on other faces: denial, anger, fear, calculation.

“Ethan, what the heck? I was kidding.” Her voice pitched upward on kidding, an actress begging the director for another take.

“Was it a joke when you were with your boss last Tuesday?” I asked.

She blinked. “I don’t know what you’re talking—”

I held up my phone. Photo: the steakhouse booth, her hand on his forearm, his eyes pinned to her mouth. “Daniel Reed is thorough.”

“You had me followed,” she said, chin lifting, offense like armor.

“I had my suspicions confirmed. There’s a difference.”

She tried to shoulder past me. “This is my house too.”

“Actually, it’s not,” I said, calm enough to scare myself. “Check the Cook County Recorder. Caldwell, Ethan—owner. Purchased before we married. Illinois is clear on premarital assets. You have thirty days to find alternative arrangements.”

Something purple drained from her cheeks. She hadn’t read the closing documents because she had nails.

“You can’t just—”

“I can and I am.” I turned as my phone rang. Unknown number.

“Hello?”

A voice I recognized from business channels: smooth, coddled by microphones. “This is Garrett Whitfield. I think we need to talk.”

Brooklyn lurched for the phone. I stepped back. “Mr. Whitfield, I was wondering when you’d call.”

“You’re making a mistake here, Caldwell. This doesn’t have to get ugly.”

“You’re absolutely right,” I said, meeting my wife’s eyes. “It doesn’t have to get ugly.”

I hung up.

“Ethan, please—” Brooklyn started.

I opened the door, stepped inside, and closed it gently. The law taught me the thing that grief never will: emotion is the enemy of outcome. Anger makes you sloppy. Hurt makes you stupid. But cold calculation? Cold calculation wins summary judgment.

In the quiet that followed, I worked. I built a list. I started a file. I moved through a house that had just shifted its gravity.

Brooklyn’s behavior hadn’t changed with a bang; it had eroded. The late nights began in March. Then came new clothes that outpaced a marketing manager’s paycheck. The sudden, pathological attachment to her phone. The showers the moment she got home, even when she hadn’t sweated. Alone, each item was domestic trivia. Together, they were a narrative.

Daniel’s file collected the facts. Hotel receipts charged to a corporate card. Security footage that couldn’t be explained by “we were just talking.” Calls that hopped towers at midnight. And the photograph that sealed it: the Bentley, the warehouse, the universal language of bodies in the back seat.

Brooklyn texted me at 10:37 p.m. that night: please let me explain. it’s not what you think. It was exactly what I thought. The only surprise was how ordinary it was. The cliché isn’t the betrayal. The cliché is their lack of imagination.

What wasn’t predictable was what I intended to do about it.

I sat at my dining table under the soft light of a lamp we picked out together and researched Garrett Whitfield like he was a target company. Open-source. Public records. Business filings. Court dockets. He was impressive on paper: Whitfield Luxury Properties—half a billion in revenue. But the filings whispered other songs. Unusual turnover in marketing and event roles—young, attractive. Two HR complaints settled without litigation and scrubbed by a crisis PR firm that specializes in de-escalating narratives. A personal life curated for men’s magazines: fast cars, philanthropic galas, black-tie smiles with Sloane. He thought money made him stormproof.

He was about to learn otherwise.

Brooklyn arrived the next morning at 8:09 with croissants and coffee and an expression engineered by mirrors. She stepped into the kitchen like a peace treaty and set down the bag like it was an offering at a temple.

“Can we at least talk?” she asked, voice soft. “Five years deserves a conversation.”

I took the coffee and remained standing. “Talk.”

“This thing with Garrett—it just happened. It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Which thing?” I asked. “His office? His car? The Palmer House last Tuesday?”

The act slipped for an instant and I glimpsed the person beneath—the one who always believes she can turn a judge with a smile. “You really did have me followed.”

“I had facts verified,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

She tried tears next, because tears had currency in our house long after the gold standard fell. “I love you, Ethan. This was just a mistake.”

“A mistake is forgetting to pick up dry cleaning,” I said. “This was a series of decisions strung together like a necklace you wanted me to admire.”

Her jaw tightened. “You’re being cruel.”

“I’m being accurate.” I pulled up the Bentley shot. Her eyes flinched. “Does Sloane Whitfield know about her husband’s hobbies?”

A sound left her that wasn’t a word.

“You wouldn’t,” she said.

“Why wouldn’t I?”

My phone rang. Daniel Reed.

“You need to see something,” he said. “Can you meet me in an hour?”

I left Brooklyn in the driveway, holding a bag of pastries like an apology. She finally understood that her life’s choreography had encountered an uncooperative stage.

Daniel picked a diner in Uptown with red vinyl booths and the kind of coffee that can shine a badge. He sat in a corner with his back to the wall, a habit no retirement can shake, a manila folder already open.

“Your timing,” he said, nodding at my tie—still straight, though I didn’t remember tying it—“could be better, but we work with what we get.”

“What am I looking at?”

He slid me a page with clipped emails. Company addresses. [email protected] to [email protected]—my wife. And another thread that introduced a private Gmail address for more “flexible comms.”

“And this,” he said, tapping another sheet. A screenshot of calendar entries. Palmer House—Board dinner followed by Post-dinner debrief in an innocuous gray block. “Security footage lines up.”

“Anyone else?” I asked.

He considered. “There’s someone who wants to be. A junior at Whitfield—events coordinator. Kept her out of the frame. But if this goes public she’ll be the one burned and she knows it. She’s willing to talk to the right person. Not press. The wife.”

The wife.

I stirred the diner coffee and watched an oily shimmer catch the fluorescent light. “What do you have on Sloane?”

“Public stuff?” Daniel said. “Former AUSA. Smart. Married ten years. Her father likes the sound of his own gavel. Not someone who misses much. Which suggests either she hasn’t had reason to look—or she has and chose to contain it. What she didn’t have before is this.” He tapped the file. “Documentation you could teach a CLE course off of.”

I nodded. My mind mapped procedural paths the way it does when a negotiation turns: what’s admissible, what’s leverage, what’s dynamite.

“Ethan,” Daniel said, lowering his voice, “how far are you willing to go?”

“As far as I need to,” I said. “Not to punish. To clarify.”

“Clarify,” he repeated, as if testing the shape of the word between his teeth. “All right. Then you need to think like a prosecutor and a PR firm at the same time. You don’t file this. You hand it. You hand it to the one person with both motive and means to end this without splatter. You hand it to Sloane.”

I looked at a photograph of my wife in a lobby I’d walked through to attend fundraisers where I shook hands with men who never learned my name. I thought about Garrett’s voice on my phone—This doesn’t have to get ugly—and the way he had said ugly like it meant public.

“No leaks,” I said. “No scorched earth. Just… place the truth in the right hands.”

“Exactly.” Daniel pushed a thumb drive across the table. “You do it today. Before they circle wagons.”

I paid for the coffee and left a twenty because the waitress looked like she’d break you like a stack of plates if you didn’t respect the house. Outside, the city had become a stage again—cars, horns, a siren somewhere near Lawrence, a kid on a scooter cutting a too-tight turn. I slid the drive into my pocket and felt the weight of something that shouldn’t weigh anything at all.

On my way back to Lincoln Park, I called the number I’d pulled from a bar exam alumni database—not Sloane’s direct line at the firm (too monitored), not her assistant (too gossipy). Her pro bono intake clinic number. It routed to her cell twice a week. If I was lucky, I’d catch it.

“Whitfield Legal Outreach,” a woman’s voice said, clipped, efficient, cordial enough to treat strangers like humans. “Sloane speaking.”

“Ms. Whitfield,” I said, “my name is Ethan Caldwell. I believe your husband is endangering your career, your family, and your father’s reputation. I have documentation. I’d like to give it to you privately.”

There was a beat. You could feel a prosecutor measuring variables in the silence.

“What kind of documentation?” she asked.

“Dates, times, hotel receipts, security footage logs, call transcripts—and a junior employee who will speak to you off the record.”

Another beat. A scrape; she’d set down a pen or stood up or both. “Where?”

“Somewhere without windows,” I said, because I wanted her to understand the scale.

She exhaled, a decision leaving her mouth. “There’s a conference room at the clinic. 4 p.m. Ask for Room Three. If you’re playing games with me, Mr. Caldwell, you will regret it.”

“I know,” I said, and I meant it. “And I’m not.”

I hung up and turned left on Damen. In the rearview, a familiar BMW shadowed two blocks back. Brooklyn had always been the kind of person who mistook a tail for a plan. She turned when I turned and then peeled off because the performance only works if the audience is watching.

Back home, I found a suitcase in the hall. Brooklyn had packed quickly, which meant carelessly. A long silk robe peeked out under a rolled blazer, and a textbook-thick flat iron sat in a tote like a brick. She stood in the living room holding a cup of coffee she hadn’t drunk and a face that had practiced heartbreak since she was sixteen.

“Daniel?” she asked, eyes flicking to the drive-sized bulge in my pocket.

“Daniel,” I said.

“Ethan, please don’t do this.”

“You did it,” I said. “I’m just describing it to the necessary parties.”

“Garrett will bury you,” she said, and there it was—the old Brooklyn, the one who believed men like Whitfield could call down storms. “He has lawyers—”

“So do I,” I said, because the simplest sentences were best. “And so does Sloane.”

She stepped forward, took my wrist with fingers that used to feel like home. “I made a mistake.”

“Multiple,” I said. “Over multiple months.”

Her hand fell away. Her eyes cooled. “You’ll be alone forever,” she said, which is what people who never sit with themselves say when you refuse their narrative.

“Maybe,” I said. “But I’ll be honest.”

At 3:41 p.m., I walked into a clinic conference room with no windows. Sloane Whitfield was already there, hair back, suit dark, expression like a judge reading a file she knew she would sign. She didn’t stand. She didn’t offer a hand. She didn’t waste my time or hers.

“Put it on the table,” she said.

I did. The drive. The printouts. The names. The photo of the Bentley like a confession on glossy paper.

She looked at the first page for three seconds, then at me for one.

“Why are you doing this?” she asked.

“Because my wife sent me a joke,” I said, and felt how ridiculous that sounded. “Because your husband thinks the world is a room he can redecorate. Because some truths belong in the hands of people who can act on them.”

Her mouth made the shape of a non-smile. “You could have gone to the press.”

“I don’t want clicks,” I said. “I want a conclusion.”

Something like respect flickered. “Then you called the right number.”

She turned the page. The clock in the corner ticked. Somewhere a siren was unspooling into the afternoon. I sat across from a woman whose life I was about to break with the gentlest tool I owned: evidence.

There’s a point in every deposition when you realize what the answer is going to be before you ask the question. In that room, that point arrived silently. Sloane closed the folder, lifted her eyes, and made a phone call without leaving the table.

“Judge Blackwood, it’s me,” she said. “We need to talk. Now.”

The fuse had been lit.

Part Two — Chain of Custody

Room Three had no windows and no softness. A clock ticked in the corner like a witness. Sloane Whitfield turned pages without flinching, as if each sheet were a rung on a ladder she already knew how to climb. When she finished, she rested her fingertips on the folder, a pianist above the keys.

“Who else has this?” she asked.

“Me,” I said. “My investigator. And now you.”

“Not the press?”

“No.”

She studied my face, looking for performative righteousness. “And your motive?”

“Clarity,” I said. “I’m not looking for money. I’m not looking for headlines. My wife detonated our marriage by text and your husband thinks he can expense the blast. That’s my motive.”

A tiny muscle in her jaw jumped once, then went still. “You’re a lawyer.”

“Yes.”

“Then you know what I’m going to ask for next.”

“Chain of custody.”

She slid a legal pad across the table. “Dates. When you obtained each item. From whom. Under what authority. Your PI’s credentials. His methods. If any of this was acquired illegally, it dies before it’s born.”

“It wasn’t,” I said, and started writing. She called in a clinic administrator to notarize my affidavit. Daniel met us twenty minutes later with his own, clean and tight, cop neat. He brought the junior events coordinator, too—nervous, mid-twenties, clutching a tote bag like a shield. Sloane didn’t interrogate her; she invited her to sit and offered water, then led her through a statement with the soft precision of a surgeon. The young woman spoke of “inappropriate comments,” “after-hours strategy sessions,” and a “mentor relationship” that everyone understood for what it was. No camera. No recorder. Just notes in Sloane’s brutal shorthand and a notary seal at the end.

“Thank you,” Sloane said to her, voice human again. “We will protect you. Starting now.”

The woman nodded, tears wobbling but not falling, and left with Daniel, who promised to drive her home.

Sloane closed the folder and breathed out, not like a sigh but like the calm a runner finds at mile four.

“I’m going to ask you to do three things,” she said to me. “First, do not contact my husband again. Second, send a litigation hold letter to Whitfield Luxury Properties’ general counsel—tonight—regarding spoliation of evidence related to expense reporting, travel logs, internal messaging platforms, and HR complaints. You will CC me, my firm, and opposing counsel if and when a divorce becomes formal. Third, file whatever you intend to file tomorrow at 9:01 a.m. and keep your filings dry. No adjectives. Facts only.”

“You don’t want a courtesy heads-up to Garrett before I send the hold?”

Her eyes flashed something like amusement. “I believe I just gave him one by calling my father.” She tilted her head toward the hall, where a tall man with silver hair and a face like a granite coin had appeared, reading the room in a single sweep.

“Judge Blackwood,” she said, “Mr. Caldwell. Mr. Caldwell—my father.”

We shook. His hand was cool and dry, the handshake version of a bench ruling: efficient, final.

“Mr. Caldwell,” he said, “my daughter tells me your documentation is… robust.”

“It’s careful,” I said.

“Good.” He turned to Sloane. “General counsel?”

“Already scheduled,” she said. “7 p.m., our place. You’ll be there.”

“Always,” he said, and left, his phone already at his ear.

Sloane slid her card across the table. “You’ll get an email with the exact language for the hold notice and a template for your separation letter. Modify as you see fit. But Ethan—keep it surgical.”

“Understood.”

She paused. “You did the right thing coming to me.”

“I didn’t come for absolution,” I said.

“Good,” she said, standing. “Because you won’t get any here. You’ll get an outcome.”

On the drive home, my phone lit up with a voicemail from Garrett. His tone had shifted from velvet to concrete.

“Caldwell,” he said, “we can do this the easy way or the hard way. You’re angry—that’s clear. Take a week. Think about what you’re doing to your wife. Think about her future employment, her reputation. I’d hate to see a person with your potential crippled by a personal vendetta.”

He ended with a lawyer’s smile I could hear through the wire. I didn’t call back.

At a red light on Diversey, a text from an unknown number came through: We should talk. Woman-to-woman. —S. Sloane was already moving pieces I couldn’t see.

Brooklyn was sitting on the front steps when I pulled in, her suitcase beside her, a coffee gone cold in her hands. She stood as I approached, eyes red but dry, the performance spent.

“I told my boss I’m taking a leave,” she said. “I told my mother I’m staying with a friend.”

“Are you?”

“No,” she said, a strangled laugh catching. “Apparently my friends like stable husbands.”

We stood there, neighbors walking dogs, the world politely ignoring our implosion.

“I’m filing at 9:01,” I said. “You’ll get served at work to avoid a scene here. You have thirty days to move out. The house is mine. You know that now. We’ll divide the joint accounts equitably minus dissipation—I’ll attach the math. I will not disparage you publicly. You will not disparage me. You will seek employment separate from Whitfield Luxury Properties.”

Her face jerked at that last line. “He said he’d—”

“Of course he did,” I said. “You were always a story for him.”

She swallowed. “Is there anything I can say that changes this?”

“Only the truth,” I said. “But truth doesn’t undo choices.”

She nodded once, small, and picked up her suitcase. “Goodbye, Ethan.”

“Goodbye, Brooklyn.”

She walked to her BMW, shoulders squared like a woman going to a job she no longer held.

Inside, I drafted the litigation hold letter with hands that had returned to steady. I kept it clean:

Dear General Counsel,

Please be advised that litigation is reasonably anticipated regarding misuse of corporate funds, hostile work environment complaints, and related marital dissolution proceedings. Demand is hereby made that your organization preserve, without alteration or destruction, all documents and ESI relating to: (a) corporate credit card expenditures for lodging, meals, and transportation attributable to Mr. Garrett Whitfield from March 1 to present; (b) access logs for company messaging systems; (c) HR complaints pertaining to Mr. Whitfield; (d) any communications between Mr. Whitfield and Ms. Brooklyn McKay. This notice triggers your duty to preserve. Failure to do so will result in sanctions.

I CC’d Sloane, her firm’s general address, and my personal attorney, a no-drama partner named Patel who had shepherded a dozen executives through divorce without a single tabloid mention. Sloane replied in under two minutes: Received. Thank you. —S Then, a second later: If Whitfield GC calls you, do not engage. Forward to me.

At 6:58 p.m., a calendar ding flashed: Emergency Meeting — Whitfield Penthouse. I wasn’t invited, of course. But in my mind’s eye, I saw the cast: Sloane, posture like a metronome; Judge Blackwood, a quiet storm; Whitfield’s general counsel, the color of ash; the board chair, a man who counts numbers instead of sheep; and Garrett, in a shirt that cost more than a rent check, walking in late and trying to own the room.

I went for a run along the lake. The air tasted like metal and memory. I clocked miles, not because I’ve ever been fast but because I needed to turn thought into breath and then into nothing. When I got home, I showered in hot water long enough to peel away the day, then chopped vegetables and made a skillet of food I could eat standing up. My house was quiet in a way that wasn’t empty. It was what quiet is supposed to be: not the absence of noise, but the absence of threat.

At 9:13 p.m., my phone vibrated. A text from Sloane: Handled. Do not contact him. File at 9:01. —S

I thumbed back one word: Understood.

The next morning at 8:59, I stood outside the clerk’s office with Patel. She’s shorter than me, stronger than most men I know, and speaks in sentences that leave no place to hide.

“You’re sure you want to keep it clean?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “No adjectives.”

She smiled. “My favorite kind of petition.” We filed: dissolution, equitable division, acknowledgment of premarital property, claim for dissipation of marital assets post-March 1. We requested exclusive possession of the residence, temporary restraining order against harassment, and mutual non-disparagement. Dry as chalk. Devastating as winter.

By 10:30, the process server had texted a photo of a stunned Brooklyn receiving the envelope at her office door, then turning on her heel and walking to a stairwell like a diver seeking air. It felt cruel in the way surgery feels cruel. Necessary. Bloody. Clean.

Around noon, Whitfield Luxury’s general counsel responded to my hold letter with the world’s blandest acknowledgement: We are aware of our obligations. Preservation protocols have been initiated. I forwarded it to Sloane without comment.

At 2:15, a reporter called from a business weekly. “Mr. Caldwell,” she chirped, “we’re hearing whispers of unrest at Whitfield Luxury. Off the record?”

“Nothing to add,” I said, and meant it. She tried twice more before giving up with a polite, irritated sigh. I hung up and turned my phone facedown like a boundary.

At 3:02, Brooklyn texted: I got served. I’ll be out in thirty days. I’m sorry.

I typed nothing. There is a mercy in silence that people who’ve weaponized words never comprehend.

That evening, Sloane called. Not text. Not email. Voice.

“I thought you might want to know the immediate outcomes,” she said, businesslike.

“I appreciate it.”

“The board convened. General counsel presented your hold notice and our documentation. Your PI’s chain-of-custody would make a first-year weep. We confronted Garrett. He denied. Then minimized. Then attempted to reframe. It was… instructive.”

“I can imagine.”

“You don’t have to,” she said. “Here are the facts. He will step down as CEO pending an internal investigation and external audit. He will be placed on paid leave through the end of the quarter with limited access to company systems. HR will conduct interviews. The junior events coordinator will be offered a transfer and a raise. And, as for my marriage—” She stopped. When she spoke again, the steel had warmed but not softened. “I spoke to my father as a daughter, not as a former AUSA. I will file for divorce. Quietly. Efficiently. Without adjectives.”

“Understood,” I said. We were two people on opposite ends of the same machine.

“One more thing,” she said. “Your wife texted me.”

Of course she did. “What did she say?”

“That she was sorry. That she was manipulated. That she didn’t want to lose her job.” Sloane’s pause wasn’t cruel; it was careful. “I told her employment decisions rest with Whitfield Luxury’s HR, not the CEO’s wife. Then I told HR to evaluate her on merit, not scandal. We don’t destroy women for men’s lies if we can help it.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it in a way that surprised me.

“This doesn’t make you a hero,” she said, as if reading a thought I wasn’t having. “It makes you useful.”

“I’ll take useful,” I said.

“Goodnight, Mr. Caldwell.”

“Goodnight, Ms. Whitfield.”

I hung up and stood in my kitchen in the soft orange of a Chicago dusk sliding down the sky like a curtain. I thought about all the words I hadn’t said in the last forty-eight hours: the curses I didn’t throw, the accusations I didn’t blast across feeds, the monologues I didn’t deliver to an audience of friends hungry for drama. I thought about how much of the law is simply restraint, and how much of love should have been.

At 10:22, an email arrived from Patel: Draft Separation Terms. I read them once, then again, and made three edits: a line protecting Detective—the cat I’d rescued and Brooklyn tolerated; a clause requiring return of any physical or digital property belonging to me or my LLC; and a sentence that felt like a benediction and a boundary: The parties agree to live as though the other no longer exists in the public square.

I printed two copies and signed one. Then I stood at the bookshelf, ran a hand along the spines, and slid the signed copy into a plain envelope. I wrote Brooklyn on the front and set it on the hall table next to the bowl where we used to drop our keys.

Garrett didn’t call again. Brooklyn did, twice, then stopped. Sloane sent a curt message the next day: Filed. The business weekly ran a three-paragraph item about “executive transition” at Whitfield Luxury Properties, citing “personal reasons” and “board confidence in the company’s long-term strategy.” No adjectives. A photo of a skyline that meant nothing and everything.

Neighbors waved the way Midwesterners do when they know and are too polite to say it. My mother left a voicemail that said only, “I love you, call me if you want to hear my voice.” I listened to it once and saved it.

On Friday, I came home to find a cardboard box on the porch. Inside: a wedding photo, three coffee mugs, two sweaters that smelled like laundry and a perfume I now associated with conference room lies, and a note in Brooklyn’s round, unsteady hand: I’m sorry I made our life a story I couldn’t keep straight. —B.

I carried the box inside, set the photo aside, and took the mugs to the sink. I washed them one by one and stacked them to dry. When I finished, the house felt the same size as the day I bought it and signed my name, single and sure, on a line that felt like a promise to a future I couldn’t name yet.

That night, Detective jumped on the bed and took the empty half without asking. I laughed out loud in the dark and didn’t apologize to the cat or to the air.

The thing about turning someone’s game against them is that you have to be willing to stop playing when you win. You have to be willing to put the ball down, walk off the court, and go home to a quiet that isn’t a punishment, it’s a practice.

Tomorrow, I would take the signed separation to Patel’s office. Next week, I would tell Angela at reception that I was fine, and I would mean it in the way people who have told the worst truth can mean it. Next month, my house would be fully mine again, not by law but by feeling.

For the first time since the text, I slept through the night.

Part Three — Aftermath, Without Adjectives

The week after we filed, Chicago put on its usual April mood: gray sky, wind that makes a person lean, sun in brief coins through clouds. I went back to court on a merger dispute and said good morning to a judge who had no idea that seventy-two hours earlier I’d dropped a different kind of pleading into a different kind of room. The law is good at pretending every case is just a case. That helps.

Brooklyn moved fast the way people do when they’ve never built anything that could stand still. A “mutual separation” post went up on her Instagram: a photo from somewhere coastal, our hands with rings cropped just so, a caption that said we still have love and respect for each other, please respect our privacy. Comments poured in. Hearts. Prayers. A few passive-aggressive friends who have never lost an argument because they’ve never admitted they were in one. I didn’t like it. I didn’t correct it. Silence traveled farther.

Sloane didn’t text for three days. That was its own message: she was working.

On Thursday morning, Whitfield Luxury Properties filed an 8-K. “Executive transition.” “Personal reasons.” “Independent review.” It was three paragraphs of nothing that told anyone who reads filings everything. A portfolio site picked it up and turned it into a bullet list. A business radio host used “sources familiar with the matter” the way a surgeon uses anesthesia. Still no adjectives.

At 11:06 a.m., Patel forwarded a PDF—Garrett’s lawyer’s letter. It was the kind of cease-and-desist you can buy with a black card and a bad conscience. It accused me of tortious interference, intentional infliction of emotional distress, defamation, and “malicious publication of private facts.” It demanded I retract “all false statements” and “cease communications with Ms. Whitfield,” capitalizing Ms. as if that might obscure the irony. It threatened “immediate legal action” and “aggressive discovery.”

Patel had already drafted the reply before I finished reading.

Counsel—

Your client is on notice of preservation obligations. My client’s statements are true, supported by documentary evidence, and, where communications with Ms. Whitfield are concerned, privileged and protected. Any action you file will be met with counterclaims for abuse of process and sanctions. My client declines to engage further. Kindly direct all future correspondence to our office.

—Patel

I asked if we should include adjectives for once. She smirked—her closest form of laughter. “The court prefers nouns.”

At lunch, Daniel called. “You’ve got a shadow,” he said. “Black Escalade, no plates on the front, tinted to the legal line, loitering on your block the last two evenings. Could be a private firm. Could be Whitfield’s idea of pressure. Stick to your routes. Document. Don’t engage.”

“Copy,” I said. I went to the window and saw nothing. Good PIs make you see even when you can’t.

That night, as I carried groceries in, a man stepped from the shadow near the elm by my stoop. Tall. Clean shoes. An expensive jacket built to look casual. He didn’t introduce himself because men like him think they are the introduction.

“Caldwell,” he said, voice smooth enough to make a room forget the knife. “Walk with me.”

“Who’s asking?”

“Someone with a mandate to solve problems.”

“Mine are solved,” I said, and kept moving. He moved with me.

“We both know that’s not true,” he said. “There are ways to make this easier for everyone. A payment. A nondisclosure. A public statement of regret for—what was the phrase—misinterpretation. You get money. We get quiet.”

“Tell your client,” I said, “that I don’t sell the truth.”

He stepped a half-inch closer. “You sure you can afford not to?”

I lifted my phone. The camera beeped. I didn’t point it at him; I pointed it at his shoes, the curb, the corner of his jaw. Enough to dissuade. Not enough to bait.

“Leave,” I said. “Future contact goes through counsel.”

He held the eye contact a second too long, then peeled off the way a stain comes off good fabric if you don’t rub it. I sent Patel a description, date, time. She replied with a one-sentence email to Whitfield’s counsel: Your client’s agents are to avoid our client’s residence and person. Any further approach will be met with an emergency motion for a protective order. No adjectives.

Brooklyn asked for coffee. Patel didn’t have to tell me that I could say no. I said yes and picked a café two neighborhoods from where either of us lived. A table by the window. Two cups between us like a deposition prop.

She looked smaller without the story around her. Not physically—Brooklyn is the same height she has been since I met her in a bar where she laughed like the room existed to make her laugh—but the kind of small that happens when a person runs out of script.

“I wanted to say it in person,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

“You already did,” I said. “In the note.”

She nodded. Her hands worried the cardboard sleeve. “I thought I could spin this,” she admitted, then winced at her own word choice. “I thought if I controlled the frame, it would hurt less.”

“It does for a while,” I said. “Until it doesn’t.”

She took a breath. “He told me—” She stopped. Corrected. “Garrett told me it was… complicated with Sloane. He said they weren’t… them anymore. He said he loved me.” She let out a humorless sound. “I believed him because I wanted to believe him. That’s not an excuse. It’s me telling you the truth.”

I looked at the girl I’d married—the one who cried during movies where no one else cried, who left the lights on in every room like a runway back to the bed, who made me laugh during a blizzard when the power went out and we ate cereal by flashlight. People don’t vanish when they betray you. They become two people at once, and you’re supposed to pretend you can’t see both.

“You made choices,” I said. “I did too.”

“Do you hate me?”

“No,” I said, and watched her shoulders flinch at the unexpected mercy. “Hate takes more energy than I’m willing to give this.”

She nodded again, then rallied for a question she must have practiced: “Is there any path where we… I don’t know. Not now, but someday—”

“No,” I said, because I owed her the kind of clarity I wished she had owed me. “Someday is a way to keep a person on a string.”

She blinked hard and let it go. “Okay.”

We talked logistics. She’d found a small sublet in Ravenswood. She’d take the Prius, I’d keep the Subaru. She wanted the Dutch oven we’d bought with a wedding gift card. I said yes. She offered to split the cat’s vet bills if I wanted. I said I could handle them. We signed the agreed temporary orders in the courthouse’s beige hallway the next morning, standing apart while a clerk stamped us with a sound like a gavel from a cartoon.

When she left to catch the elevator, she turned back. “You don’t have to be this cold,” she said, and for the first time there was anger in it—not at me, exactly, but at the way her tools had all turned to wood.

“I’m not cold,” I said. “I’m precise.”

She didn’t argue. The doors closed.

News moves like water in a closed system. It finds the path of least resistance and makes it a channel. By the second week, whispers turned to statements you could attribute without losing a source. The board installed an “interim chief restructuring officer.” A small avalanche of “exiting to pursue other opportunities” hit the company page. A long, careful story ran in a weekly under the headline Luxury Developer Faces Culture Questions. It contained exactly one sentence that mattered: A person close to the matter provided documentation of expense irregularities and internal complaints. No names. No adjectives. No lawsuits filed in response.

Sloane texted once: Interviewing. Clean. Then, a day later: Filed petition today. Served. She didn’t attach a smiley. She didn’t need to.

Daniel called to tell me the junior events coordinator had taken the transfer Sloane arranged—to compliance. “She says thank you,” he added, and then, under his breath, “for not making her proof of anything.”

“Tell her I said what you told her,” I said. “That she doesn’t owe me thanks.”

He grunted, his version of approval. “Two more things,” he said. “One, Whitfield hired a different firm to dig on you. They’ll find a clean house and a well-labeled file cabinet. Two, your mother called me.”

“My mother called you?”

“She used the number on my card,” he said, wry. “Said she didn’t want to bother you. Wanted to thank me for keeping you safe from foolishness.”

I laughed despite myself. “She talks like boilers used to be furnaces,” I said. “Tell her she can bother me.”

“Already did,” he said, and hung up.

A week later, I was walking out of the parking garage under my office when a black Bentley slid across the alley like a sentence meant to block a door. Garrett stepped out and did the thing where he pretended he didn’t know he was blocking my way. He wore the kind of suit that calls itself classic while costing two mortgage payments. He didn’t look at me. He looked at my reflection in the chrome.

“You cost a lot of people a lot of money,” he said.

“No,” I said. “You did.”

He turned then, smile just shy of teeth. “You think you won because you made a phone call.”

“I think I did what I had to do because you thought you were the exception to rules you pay other people to enforce.”

He took a step closer, just enough to test it. “You still have to live in this town.”

“So do you,” I said.

We stood like that for a second: two men who hate theatrics pretending not to be in one. Then a garage attendant yelled Sir at the Bentley and Garrett flinched at being called sir by someone who meant move. He slid back behind the wheel and was gone without squeal. His kind never squeal. They glide. It’s the sound they make when the ground finally gets a grade under them that tells you things have changed.

I texted Patel a summary. She responded with a copy-paste she’d prepared the day after we filed: Any attempt to contact my client directly will be considered harassment and reported accordingly. All communications must go through counsel. She already had the email in Whitfield’s lawyer’s inbox before I put my phone away. The system works when the people in it do.

At home on a Sunday, I cleared out the hall closet. Coats we hadn’t worn since a winter before we knew the names of our neighbors’ kids. A purse with a ticket stub in the inner pocket from a band we saw on a summer night when we walked back barefoot because we didn’t want to ruin good shoes in a thunderstorm. A shoebox with letters. I read none of them. I didn’t need the narrative backstory. The facts had been enough.

I set aside what was hers. I kept what was mine. I threw away the rest. Precision masked as minimalism. The house exhaled.

Neighbors kept waving. One, a retired teacher who has watched people move in and out for thirty years, caught me by the hedge with clippers in my hand and said, “People will try to tell you the moral of your own story. Don’t let them.”

“I won’t,” I said.

“Good,” she said, then pointed at the lilac. “Cut that lower. It’ll bloom better.”

I cut it lower.

Two hearings later, temporary orders became permanent orders. No trial. No fireworks. Patel in a navy suit with a folder. Brooklyn with a lawyer who took careful notes and looked tired of seeing this same math. The judge—a different one than I’d seen on my merger matter—reviewed our stipulations and signed. The sound of the stamp was quieter this time. Maybe I was listening differently.

After, in the hallway, Brooklyn approached. No script now. Just something like relief and grief mixed until you can’t tell them apart.

“Thank you for not trying to destroy me,” she said.

“You did that without my help,” I said, regretted the line as soon as it left, then added, “You’re welcome.”

She nodded. “I’m going to stay off social for a while,” she said. “Start over somewhere that isn’t a feed.”

“That’ll help,” I said.

“You really loved me,” she said, not as a question.

“Yes,” I said.

She nodded again, the way people do when the only thing left to do is nod. Then she walked away and didn’t look back, which was its own kind of mercy.

That evening, Sloane texted: Final interim order entered in Whitfield matter. Audit continues. Thank you for your restraint. I wrote back: Likewise. Then: I made a donation to the clinic. She sent a period in reply—a full stop. Perfect punctuation.

I grilled a steak on the back deck as the sky gave the city a color it doesn’t keep. Detective lay on the warm boards and blinked like someone who lives entirely in the present. I ate standing up, the way I had the night after the first filings. It wasn’t a ritual. It was a habit. Rituals are what you call habits when you want to pretend they’re holy.

When the dishes were done, I opened the box Brooklyn had left weeks ago and took out the wedding photo. Two people in fresh clothes making promises with their mouths open. I didn’t put it back on the shelf. I didn’t smash it. I wrapped it in the paper it came in and slid it into a drawer where I keep tax returns and user manuals. True. Archived. Available if needed. Not for daily use.

I slept. In the morning, I woke before the alarm out of practice, not fear.

This is what I learned by doing the least dramatic thing possible in the most dramatic moment of my life: sometimes the cleanest justice is the kind no one claps for. It is filings and letters and doors closing without slams. It is saying no when maybe would win you sympathy. It is starving the part of you that wants spectacle and feeding the part that wants a life.

There would be a final act. There always is. A board vote. A resignation. A settlement sealed with a confidentiality clause people will speculate about and never read. A divorce decree that enters the record and then recedes. An end that isn’t flames, just a light turned off in a room you no longer need.

That’s what comes next.

If I have anything to say about it, that’s how it ends.

Part Four — Clean Exit

The board met on a Tuesday.

I knew the hour because business filings tend to cluster at certain times the way planes prefer certain runways. At 3:31 p.m., Whitfield Luxury Properties posted a release: Garrett R. Whitfield Resigns as Chief Executive Officer, Effective Immediately. The boilerplate did what boilerplate does—thanked him for his service, praised the company’s “strong fundamentals,” named an interim executive with a résumé built of verbs instead of photos. There was no mention of culture reviews, no acknowledgement of the reasons anyone reading it had already guessed. But the picture on the investor page changed before the minute did.

No adjectives.

Sloane texted exactly seven words. Board vote unanimous. Audit preserved. That’s done. Then another: Decree next.

Brooklyn’s and my divorce proved as uncinematic as we had designed it to be. Patel walked me down a narrow corridor painted the same beige as every courthouse I’ve ever wondered about lunch in. We sat on a bench. A bailiff called cases in a tone that could put out fires without water. When our turn came, the judge read our stipulation with the speed of a person who wants to be right more than she wants to be charming, asked our lawyers two questions to confirm voluntariness and capacity, and signed.

The stamp didn’t sound like thunder anymore. It sounded like a door latch inside a well-built house.

We stepped into the hallway. Brooklyn’s lawyer shook Patel’s hand with professional relief. Brooklyn stood with her back to the window, the light making a halo of a woman who wasn’t an angel and didn’t claim to be. She held out a sheet of paper—her copy of the decree—and managed a smile that had no audience.

“Looks like we actually did it the right way,” she said.

“Looks like,” I said.

“Can I ask one more thing?” she said. “When people ask… do I tell them it was my fault?”

“Tell them it was ours,” I said. “And tell them the rest is none of their business.”

She nodded. “Take care of yourself, Ethan.”

“You too.”

She left before me, the elevator swallowing her, the indicator light ticking down like a goodbye no one needed to speak.

I walked outside into a Chicago that had not paused for us. A bus hissed. A siren slid toward a problem I could not solve. Two bike messengers made a choreography in traffic that would have killed me if I tried it. I put on my sunglasses and stood there long enough to feel foolish and then better.

Patel tapped my shoulder. “Come on,” she said. “I’ve got a summary judgment hearing to win.”

“Go win it,” I said.

She did.

Garrett’s last gambit arrived as a letter couriered by a kid who looked like he should still be in algebra. The envelope was thick the way threats like to be thick. Inside: a proposed “global resolution.” Cash. Mutual non-disparagement expanded to include “any affiliates, family members, or associates.” A retroactive NDA that would have required me to pretend I had never spoken to Sloane or anyone who might be mistaken for Sloane. A clause that made my skin itch: “The parties agree that any violation shall entitle Mr. Whitfield to injunctive relief and liquidated damages.” The number attached to liquidated damages had more zeros than most houses.

Patel’s marginal note in pencil: Absolutely not.

We sent a response limited to one paragraph: Offer rejected. Our client has not defamed your client and will not be party to a contract that seeks to conceal true statements of material fact. Future contact through counsel only.

Two days later, a process server knocked for me. Temporary protective order hearing—my petition. Patel’s work, already drafted. I had forgotten she’d filed it as a prophylactic after the shadow by the elm. We stood before a different judge with a docket of people who needed protection from worse than men in expensive jackets. I felt like an intruder and then remembered that law is a net large enough to catch both bricks and pebbles.

“We’re not suggesting imminence,” Patel said, tone level. “We’re establishing boundaries. There have been approaches. There is money involved. There is motive.”

The judge granted the order without speech and with a pen, which is what orders are, stripped of ceremony. Garrett was barred from direct contact, barred from sending “agents” to my house or office, barred from “surveillance intended to harass,” which is as close as a court ever gets to calling a man petty.

I walked out into the same wind and felt something in my shoulders release that I didn’t know had been clenched.

Sloane asked to meet once more. Not Room Three at the clinic. A conference room on the forty-second floor, glass walls looking over a city that refuses to be impressed by itself. She wore gray. I wore the same navy I’ve worn to every ending that mattered.

“I brought you this,” she said, holding up a small evidence bag with the thumb drive inside. “Chain of custody complete. I don’t need it anymore.”

I took it like a relic, which was ridiculous and true. “And the audit?”

“Ongoing,” she said. “There will be refunds to shareholders masquerading as strategic realignment. There will be HR consultants teaching basic decency for a fee no one should have to pay. There will be noncompetes negotiated down to nothing. There will be depositions. None of that is your problem.”

“And your case?”

She allowed the smallest smile. “A tidy petition and a conscientious judge. Irreconcilable differences. Community property. I’ll keep the house, not because it matters, but because he believes it does.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I was.

“Don’t be,” she said. “Men like my husband count on people being sorry for the mess they made. He is an adult with a wallet and a phone. He used both badly.”

We stood and didn’t shake hands yet. She looked out at the lake, thin and hard against the April light.

“You did something rare,” she said finally. “You brought me facts and asked for nothing that would embarrass me. You wanted an outcome, not a scene. The world could use more of that.”

“I did want something,” I said. “Silence.”

“That’s not nothing.”

“No,” I said. “It isn’t.”

She extended her hand. I shook it. We were done.

The black Escalade stopped showing up on my block. The Bentley stayed on the other side of town. The junior events coordinator sent Daniel a photo of her new ID badge and a thumbs-up emoji that felt like a thesis on survival. Brooklyn sent a text the day she moved the last box: Keys in mailbox. Thank you for the Dutch oven. —B. I replied with a period, which in our language meant received and goodbye.

I worked. I argued a motion, lost one I should have won, won one I thought I’d lose, wrote a brief that said the contract says what it says and meant it. I ran by the lake and hated mile two and loved mile three and stopped looking over my shoulder at sirens that weren’t for me. I called my mother on Tuesday nights and let her tell me the same story about my grandfather fixing a radio no one believed he could fix as if it were breaking news. I learned to cook one thing well and one thing poorly and served both to a friend who didn’t pretend the second was good. I watched the Bulls lose the way they lose and forgave them faster than I forgive people who make vows they can’t keep.

Detective learned that the half of the bed on the window side was his now. He took it like a conquering army and snored like a grievance. I bought a new set of sheets because fresh fabric is a kind of truce. I replaced a lightbulb in the hall that had been dead since before the text and wondered why I hadn’t done it sooner.

Neighbors kept waving. The retired teacher by the hedge asked me how the lilac was liking the cut. “Blooming,” I said. She nodded like a surgeon who’s seen a thousand stitches and still approves each one.

A month after the board’s press release, Whitfield Luxury filed a document only lawyers read: separation agreement filed as an exhibit to an 8-K. Redacted, of course. But there it was in black squares and white lines: the cost of a man’s personal reasons calculated for markets. A business blogger wrote a piece headlined When the CEO Is the Crisis and filled it with words like governance and fiduciary. No one used love or betrayal because those don’t trade well.

That night, Sloane texted exactly one word: Decree. I thumbed back the same. She added a second message after a minute: Clinic fund got your donation. We’ll put it to work. I wrote: Good. She answered with a period again, perfect punctuation to end a correspondence that never flirted with becoming anything else.

On a Saturday, I took the Blue Line to the end just because I could sit and let a system move me. At O’Hare I didn’t get on a plane. I walked the terminals and watched the choreography of people leaving and returning to lives that would not be improved by my opinion. On the way back, a kid in a Bulls jersey offered me a seat and I felt both old and raised correctly. I declined and held the pole and looked at my reflection in the scratched plastic. I looked like a man whose face had learned new lines quickly and decided to keep them.

At home, I opened the drawer with the manuals and tax returns and took out the wedding photo. I looked at it for sixty seconds, exactly, the way I had stared at the text that started this. Two people young enough to think vows were a spell you cast and not a promise you had to protect with ordinary choices. I put the photo back in the drawer and shut it gently. Not a burial. A filing.

The next morning, I woke before my alarm, not because of anxiety, but because my body had learned a new time. I made coffee, black. I stood at the window and watched the first dog walkers stake out their small territories of routine. I turned on the radio and then turned it off because silence still felt like the most accurate soundtrack.

My phone buzzed. A message from an unknown number.

Unknown: You don’t know me. I’m the compliance analyst who got the transfer. I just wanted to say that when people like me survive, it’s partly because people like you choose outcomes over scenes. Thank you.

I typed and deleted three responses before landing where I try to land.

Me: You did the hard part. Be well.

I set the phone down. Detective head-butted my calf, indignant at the delay in breakfast. I fed him. He ate with the complete concentration of a creature who has never pretended to be anything but hungry.

I laced my shoes and stepped outside. The air had that Chicago trick of pretending at spring while holding winter in its sleeve. I breathed it in like something I might lose.

This is the part where the story ends without fireworks. That’s the point. Garrett resigned. Sloane got her decree and her house and, more importantly, a future she decided. Brooklyn moved out and will build a new script that I hope speaks in honest sentences. I kept the house, not because ownership is victory, but because it was mine before any of this and will be after. We all put down our weapons: the text, the GoPro, the Bentley, the boardroom. We traded them for signatures and stamps and lines in the record that no one but us will ever read.

Five years of marriage ended with a pen, not a speech. A joke text became a border. I turned a game into a process. It wasn’t cathartic. It was clean.

I started running. Not away. Just forward.

News

I FOUND OUT MY BEST FRIEND WAS HELPING MY HUSBAND CHEAT, SO I GAVE THEM BOTH A LESSON THAT MADE THEM CH2

Part One The first time I saw the hotel charge, I told myself a story. It was a Tuesday, ugly…

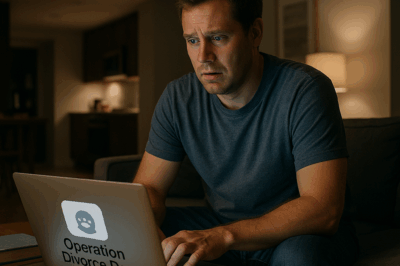

Found My Wife’s Group Chat Called “Operation Divorce Dan” With Her Sisters Planning My “Surprise… CH2

Part One — The Cold Open Three weeks before our tenth anniversary, my wife started humming again. Not a real…

There’s no one to watch my daughter—could she sit quietly in your office?” asked the secretary… CH2

Part One — The Discovery The morning sun broke through the tall windows of the Gran Agency building, spilling pale…

“My brother texted me: “Don’t go home tonight!” I thought it was a joke… until I saw the video at his place — and my whole world collapsed that night! CH2

Ashley’s laugh echoed through the speakers, bright and familiar, yet twisted now into something foreign. The man leaned in, his…

“The Truth at the Wedding” – Rewritten Story in English CH2

On the day of Rareș’s wedding, a woman stood at a distance, watching quietly. Sylwia Pietrowna, his mother, lingered near…

Daughter came to say goodbye to her mother, She notices something strange And stops the Funeral CH2

“Mom, wake up… please don’t leave me.” Nine-year-old Katie Miller pressed her small hands against the casket, tears streaming down her cheeks….

End of content

No more pages to load