Part I

I was twenty-eight, wrapped in white satin and a dozen years of borrowed dreams, standing in a Denver ballroom that looked like the inside of a champagne flute. Chandeliers threw constellations over the tables; votives lined the centerpieces like tiny, obedient suns. The room smelled faintly of roses and ganache, and every time I inhaled, I imagined my lungs filling with light. For an hour—maybe two—the night was exactly what a girl in Colorado might have imagined at twelve, staring at bridal magazines at the grocery store: music like warm wind, relatives radiant with opinions, a gold thread pulling the future right toward me.

David looked the way a photographer loves: tall, polished, an easy smile that moved through rooms like a key. He greeted guests as if he’d practiced it in mirrors, and maybe he had—he was that kind of man, the kind who learns a room by route. When his palm found the small of my back, I let myself believe I had chosen my safe place. To the outside, we were aspirational: the coordinated couple, the generous bar, the storybook.

Megan cut through a circle of bridesmaids like a kindly meteor. She smelled faintly of vanilla and lavender and wore her joy like a bright scarf. “Don’t move,” she whispered, her eyes dancing. “I brought you something you are absolutely using tonight.”

From a tote dressed in white ribbon, she lifted a long velvet box and set it beside the cake—four tiers of buttercream that rose like a well-behaved mountain. Bridesmaids leaned in; someone actually gasped. Megan flipped the brass clasps. Inside, on satin, lay a cake knife so beautiful it turned conversation into a hum. The blade, polished to a mirror, ran a clean foot; the handle twisted in silver, weighty in both hands. Along the spine, an engraver had etched: Amanda & David — Denver, Colorado and our date. Tiny crystals winked along the guard like patient stars.

“It’s… heavy,” I breathed, lifting it with both hands. It sat in my palms like a promise—the kind you present, not just hold.

“That’s the point,” Megan said, grinning. “Custom-made so your photos don’t look like every other couple’s. You two will hold it together.” She mimed the pose: one hand beneath mine, the other guiding the hilt. “Classic. Dramatic. You’ll thank me when People Magazine calls.”

Emotion tightened my throat in a way mascara hates. “You did all this for—”

“For you,” she said. “For a memory you want to keep forever.” Then, softer: “It anchors you.”

I squeezed, feeling the balance. The photographer drifted over, asked us to angle the blade toward the chandelier, and laughed when reflected prisms ran like confetti across the ceiling. Aunties whispered. Strangers smiled. Even my nerves softened, temporarily willing to be charmed into order.

Across the hall, Susan watched the way a museum guard watches a child—polite, poised, unwilling to step in until it’s too late. Her posture was theater; her smile stopped at the border of her eyes. She tilted her head as if the velvet box amused her and turned to a couple I didn’t recognize. I tried not to care. It was my moment; her face had no right to it.

“How’s she doing?” Megan murmured, meaning Susan without saying her name.

“Perfect,” I said, and we both heard not.

“I told the maître d’ to keep the knife on the display until the first dance,” Megan went on, brisk and bright. “It takes two hands to lift cleanly. They know it’s yours.”

“You thought of everything.”

“That’s my job: official maid of honor, unofficial fixer of all things. If anything feels off, look for me.”

The band slipped into Motown. Glasses chimed against stems. David reappeared at my side and kissed my temple, complimenting the knife with a practiced charm that made the bridesmaids giggle. I wanted to believe in that warmth. I wanted, desperately, to believe in the version of us the room had agreed to admire.

We posed for more photos. Time ribboned itself: toast, laughter, six separate embraces that smelled like perfume and champagne. When I set the knife back into its satin cradle, Megan closed the box with a click and slid it beneath the display’s overhang.

“Ready?” she asked, eyes bright.

“For everything,” I said, and for a heartbeat, I was.

Near the bar, a glass kissed stone in a way that made a crack more audible than it should have been. A tremor ran up from my shoes like the floor had inhaled. I shook it off. The DJ announced the first dance, and the guests opened like lace so we could step into the circle they made.

David knows how to move. He dipped me with ease, smiled just enough to reach row three, and whispered the right compliments at the right moments. Vanilla drifted from the cake; the chandeliers were patient constellations. I counted beats and blessings. When I came up from a spin, I found Susan at the edge of the floor, her lips curved for the camera, her eyes two neat knives. She stood like someone waiting for a cue.

We ended in applause. David kissed my cheek. We returned to our table surrounded by bubbles and flash. I pretended the world fit, that the day’s edges were smooth. The whisper I’d been ignoring—the one that said night can splice joy with something else—curled somewhere I refused to look.

Susan didn’t make a scene. She created one. A tilt of the head; a polite call to come closer. “Emma,” she started, then corrected, so neatly the cut hardly bled. “Amanda, dear, could you come here a moment?” Her tone was sugar you can’t swallow. I glanced at Megan. You okay? she mouthed. I nodded because denial is a beautiful drug.

I stopped a foot away, my gown whispering the polished floor.

“What is it, Susan?” I asked, evenly.

“It’s about the way you look at me,” she said. “Don’t pretend. I can see it in your eyes. Disdain. Contempt. You may fool others, but not me.”

My mouth dried. “I think you’ve misunderstood. I have nothing but respect for—”

“Respect?” She scoffed—just enough volume to turn three heads. “I hear the sighs. I see the eyes. You’ve turned my son against me. On his wedding day, you couldn’t hide it.”

A murmur moved the way wind moves wheat. I felt eyes tilt toward us, hungry. David arrived like a line in a play.

“Mom, what’s going on?” he asked, brow creased in concern that felt borrowed.

Susan clutched his arm. “Your wife has been nothing but disrespectful. She humiliates me even tonight. I won’t be treated like this.”

“Amanda?” David said, my name a test he hoped I’d fail.

“No,” I said, heat climbing my chest, a careful fire. “I haven’t—”

“I am your mother,” Susan whispered, tears arriving on schedule. “Would I lie to you?”

Something in David closed. The room held its breath. He looked from her face to mine, then across the space where the cake stood sculpted in patience, and there—half-hidden beneath the table’s skirting—the velvet box threw back chandelier light like a wink.

“No,” I said again, my voice smaller this time, the word evaporating between us.

David moved before the gasp could form. He strode to the cake, slid the box free, cracked it open, and lifted the knife Megan had chosen to be a safeguard against ordinary. The blade, so handsome in our photographs, turned the air colder.

“David,” I said. The room became a dark river. “This isn’t you. Please.”

But anger feeds on audience. He looked at his mother, at me, back at the room we’d invited. And then—in a motion I will hear in my bones until there are no more sounds to hear—he raised the knife and brought the flat of it down against my temple. The sound was dull, heavy, a book slammed in a quiet library. A cry tore out of me I didn’t know I had.

Heat spread across my scalp like water moving the wrong way. The room reassembled into scream and clatter: chairs skidding, heels scraping, a child crying in a rattle of pearl. I dropped to my knees and the world tilted; my veil caught on a chair leg like a torn sail. The music strangled itself. Photographers let their cameras fall. Somewhere in the static, Susan said something urgent I couldn’t translate.

Megan’s voice cut through. “Amanda! Hey—hey, look at me. Stay with me, babe. Don’t close your eyes. Don’t you dare.”

I tried to answer but my words had marbles in them. Metal crept onto my tongue. The chandeliers sharpened into stars; the ceiling moved farther away. When I turned my head, I saw David still holding the knife, staring down at his own hand like he’d borrowed it from a stranger.

“Call 911!” Megan shouted, suddenly a captain in a ship that had decided to tilt. A man—maybe a cousin—fumbled his phone. A woman—maybe a guest from work—declared our location with the clarity of someone who has practiced saving other people’s days. “Downtown Denver. Bride down. Head trauma. Yes, he’s been disarmed.”

“Drop it!” another voice barked—the maître d’, off-duty cop cadence in his throat.

The knife clattered. So did something in my chest. Megan pressed a napkin—then two—then her hand, firm and apologetic, against the place that hurt. “Look at me,” she said, forehead nearly touching mine, eyes green and unwavering. Her voice smoothed the edges. “You are not alone. Do you hear me? We are not letting this be the end.”

The doors burst open. Officers in dark blue swept in with the briskness of people who have to be the adults in rooms that forgot how. Behind them, paramedics pushed a stretcher, voices clipped into a choreography I trusted without understanding: pupils reactive… pulse thready… O2… c-spine. Two officers moved toward David. “Drop it,” one repeated, though the knife lay on the satin box like a truth you couldn’t un-see. Susan grabbed David’s arm, whispering, “Say it was an accident. Say—”

“Ma’am, step back,” the officer warned, voice a line with teeth.

David flinched. For a terrible second, he looked like a boy who wanted to hand someone a broken thing and ask them to fix it. Then they cuffed him, read him a script that had no room for wedding toasts, and guided him out as guests made a quiet aisle no one clapped for.

“Ride with us,” a paramedic told Megan without looking up. “Keep talking to her.”

They lifted me; the ceiling tiles became a scroll. The night air hit like truth. Cameras flashed—phones or reporters, I couldn’t tell. Somewhere, sirens braided themselves into the cold.

“You’re going to be okay,” Megan whispered as the ambulance swallowed us. “This is not your ending.”

I shut my eyes—not in surrender, but the way a diver shuts theirs to feel the surface slide past—and let the siren write a different story into the dark.

Part II

Fluorescents hummed overhead like tired bees. The gurney rattled through Denver Health’s automatic doors, metal meeting tile with a rhythm that tried to convince my pulse to cooperate. Hands—gloved, competent—tucked towels around my neck, slid a collar into place, clipped a pulse-ox to my finger. Megan moved with us like a second shadow, her palm threaded through mine no matter how the hallway bent.

“She’s with me,” she told anyone who thought to ask.

“Name?” a nurse asked, already sticking labels to vials she hadn’t filled yet.

“Amanda,” I managed. “Twenty-eight.”

“Event?”

“Wedding,” Megan said when my throat failed. “Head trauma by blunt”—she swallowed—“object.”

In the bay, curtains coughed shut. A doctor with kind eyes and a deliberately boring tie leaned in, penlight bright as a small moon. “Stay awake for me,” he said. “Any nausea? Double vision? Amanda, can you tell me where you are?”

“Denver,” I said. The syllables scraped. “Hospital.”

“Good,” he said, as if we’d achieved something monumental. “We’re going to clean this, then we’re going to scan. It looks like a deep laceration at the hairline. No skull depression palpated.” He softened his voice. “That’s promising. You’ll have a headache worthy of legend.”

Megan squeezed my fingers. “Legends look good on you,” she said, and the joke landed just enough to keep the room from tilting.

They irrigated the wound; the water ran pink down my temple and into the towel like watercolor that refused to dry. An RN braided gauze into my hair with a gentleness that made my eyes sting for a different reason. Somewhere outside the curtain, a phone rang three times and lost its nerve. A monitor beeped in two keys.

“CT’s clear,” the doctor said twenty minutes later, returning with a printout like a prize. “No fracture, no bleed. We’ll close with sutures—your hair will hide most of this—but you’ll be sore. You’ll also be angry, probably in waves. That’s normal. Don’t make any big decisions until you’ve slept and had soup.”

“Doctor,” I said, finding a strip of voice no one had used yet. “I want the report. Every page. Every photo. Everything. Tonight.”

He studied me for a beat and nodded. “We’ve already flagged this for DPD. You’ll receive copies through your case officer. But I’ll have the nurse print what I can now.” He lowered his voice. “Paper helps.”

Paper. The first thing that weighs more than rumor.

When they were done stitching and wrapping and instructing, two officers appeared at the curtain with faces that looked like they’d practiced being calm on worse nights. “Ms. Pierce?” the taller one asked (my own name landing on me like a coat that still fit). “Officer Daniels. This is Officer Grant. If you’re able, we’d like to take a statement while details are fresh.”

Megan shifted, ready to plant herself between me and anything that resembled harm. I tugged her hand instead. “I’m ready,” I said.

Officer Grant clicked a small red button on a recorder. “For the record, please state your full name and age.”

“Amanda Pierce. Twenty-eight.” The bandage tugged as I swallowed. “I was attacked at my wedding reception by my husband, David Brown, with a ceremonial cake knife. He struck me once on the left temple with the flat of the blade. I fell. My friend Megan Hayes applied pressure. Guests called 911.”

They didn’t rush me. They didn’t prod. They asked for detail like cartographers mapping a coastline they intended to defend. I told them about Susan’s tilt of the head, the accusation braided with manners, the way David’s eyes went from tethered to untied in three seconds. I told them what the room smelled like (vanilla, roses, fear), the way Megan’s voice sounded (steel wrapped in velvet). I told them that Susan said, clear as crystal: Say it was an accident.

Officer Daniels wrote that sentence like a nail hammered through wood.

“We’ve already secured the knife,” he said when I finished. “Collected guest videos. The maître d’ provided names for a dozen staff witnesses. Based on the evidence, Mr. Brown is being charged with aggravated assault and felony menacing. Ms. Cartwright—”

“Susan,” I said.

“—is being held on suspicion of incitement and obstruction. There will be a restraining order in place before dawn. Bail hearing within forty-eight hours. We’ll keep you informed.”

I exhaled and only then realized I’d been holding my breath since the chandelier broke into stars. “Do they get out?” I asked.

“That’s a judge’s call,” Officer Grant said. “But the facts are… unfavorable to them.”

Megan tucked a stray curl under my bandage with the reverence people use on altar cloths. “They won’t own a single minute of your air again,” she whispered.

As if summoned by the promise, my phone buzzed in a tray with the insistence of people who weren’t invited to this room. Unknown numbers. A cluster of texts from contacts saved under last names like Cousin Mark and Work Kirsten and Hair Aly. Headlines began to congeal online—someone in our ballroom had pressed upload as easily as they once pressed toast. The words Bride, Knife, Denver married themselves into a sentence that had nothing to do with vows.

“Don’t read it,” Megan said, catching my eyes in the reflection of the phone. “Not tonight.”

“I won’t,” I lied, knowing I would, later, in the kind of dark that makes rooms feel like caves.

The nurse returned with a stapled packet and a patient discharge sheet highlighted in kindergarten yellow. “We’ll call with suture removal in seven to ten days,” she said. “Avoid alcohol tonight, avoid stairs if you can help it, avoid men named David.”

I snorted on a breath that ached. “Working on it.”

By morning, the temporary restraining order lived in my email and on paper in a manila envelope thick enough to be a doorstop. I slept in a guest room at Megan’s—with her old cat posted like a sentry—and woke to sunlight on walls the color of a soft peach. I brushed my teeth left-handed and stared at my face. The bandage made me look like a war photo. Maybe I was. Megan brewed coffee and pretended she didn’t watch me cross the kitchen like a fawn learning asphalt.

“What’s today?” I asked.

“Today is soup and a lawyer,” she said. “Victoria Reed. Friend of a friend. She bites like a good dog.”

“Do I need a divorce lawyer already?” I tried for wry. It landed crooked.

“You need someone who can turn ‘what happened’ into ‘what they can’t wiggle out of.’” Megan slid a bowl of chicken noodle to my side and set a glass of water down like a contract. “Eat. Then we dress you like a person who knows her name.”

Victoria’s office smelled like paper and purpose. Her hair was steel-gray, her eyes matched, and her handshake said: I’m on your side, and also I will move this mountain. She listened to my story like a surgeon reading films.

“We’ll file for permanent protection orders immediately,” she said. “And we’ll coordinate with the DA. Your case is clean. There are witnesses, video, medical. You didn’t start a fight; you were the target of one. We’ll also initiate dissolution of marriage on grounds of irreconcilable differences, supported by documented domestic violence. We move quickly to define the narrative on paper.”

“What can he do?” I asked. “From jail?”

“Plead,” she said. “Post. Perform.” Her mouth tightened. “Men like this often have a second script. He may try to say he was provoked, that it was an ‘accident,’ that he ‘blacked out,’ that he was ‘defending’ his mother’s honor. The facts do not support him. The venue—the public nature of the assault—hurts him in ways juries understand.”

“And Susan?”

“She’s an accessory to the harm, if not in law then in the hearts of twelve citizens. Her whisper is on record. It will land.”

I nodded. My head throbbed in agreement and in protest. “I want… all of it,” I said, surprising myself. “Not just safety. Consequences.”

“You’ll get both,” Victoria said. “We’ll keep you off socials. If press calls, you decline or read from one sentence: I’m cooperating fully with law enforcement and focusing on my recovery. That’s it. No candor, no color. Save your voice for court.”

“I have—” I stopped, felt the embarrassment rise, pushed through it. “I have a business card. Not a business. A card. For event planning. I made it months ago. For fun. It feels… obscene to say out loud right now.”

“It’s not obscene,” Victoria said. “It’s a map. Keep it somewhere you can see. We’ll build you back a life that hasn’t been touched by their hands.”

On the drive home, Denver wore a bright December sun that made even bad things feel temporary. Billboards hawked injury lawyers and ski passes. The mountains sat like old gods minding their business. My phone buzzed with a new number. DPD Victim Services. Would I like an advocate to attend the bail hearing? Would I like a safety plan? I said yes so many times the word lost consonants.

That afternoon, the bail hearing slid past like an unpleasant commercial we were forced to watch. The judge’s voice was even; the clerk’s hands moved quick. David appeared on a video screen, orange against cinderblock, jaw set in a way that used to charm donors at his firm’s galas and now only made him look smaller. Susan’s lawyer filled her chair with sky-blue sincerity. The DA laid out the facts without flourish: public assault, weaponized object, injury requiring emergent care, attempt to manipulate narrative in the immediate aftermath. The judge read the room, the law, and the tea leaves.

“Bail denied,” she said for David. For Susan: “Released to home confinement with conditions, pending arraignment.” A GPS ankle bracelet might as well have beeped in between the words.

When the screen blinked black, I realized I hadn’t breathed for at least thirty seconds. Megan tapped the back of my hand, a Morse code for In. Out. We keep going.

Outside, a reporter angled a mic toward my bandage. “Amanda, do you feel safe? What do you want to see happen?”

Megan stepped between us like a well-dressed linebacker. “No comments,” she said, her voice the firm edge of polite. “Give her space.”

I could have kept walking. I didn’t. I turned, careful, and let the camera catch my eyes. “I feel grateful for the people who did their jobs last night,” I said. “The maître d’ who intervened. The guests who called. The officers. The paramedics. The nurses. My friend. That’s my statement.”

The mic lowered another inch. The reporter blinked. It wasn’t what the reel wanted. It was what I had.

“Unexpected,” Megan murmured when we were out of range.

“It’s the only thing I can say that’s not about them,” I said.

That night became three, then five. Sleep came in halves. I woke to phantom weight above my eyebrow, to the specific sound a knife makes hitting satin. Megan set timers to make me sip water and swallow Advil. Victoria emailed filings in PDFs dense as fruitcake. Officer Daniels called to update: arraignment set, DA confident, a hundred things moving when I was allowed to be still.

On the sixth day, I woke to quiet in my head. The cat had decided I belonged and snored into my ribs. I made coffee and watched light lace the kitchen. My phone lit with a text from an unknown number I knew bodily: Susan. We should talk. Families resolve things. My son is remorseful. You could help him. I didn’t reply. I forwarded it to Victoria, who forwarded it to the DA, who forwarded it to Daniels, who called me within ten minutes and said, “Good catch. Do not engage.”

At noon, I stood in front of a mirror without a bandage and met the jag of a new scar. It wasn’t large. It wasn’t apocalyptic. Hair would hide most of it. But it tilted my face just enough that I would never not know it was there. I traced it with a fingertip, then reached for Megan’s velvet box—empty now, evidence tagged and locked in some municipal cabinet—and slid the lid closed on nothing.

“Let’s give that day new weight,” I told my reflection. “Let’s make it hold something else.”

I opened my laptop and dragged a folder from the digital junk drawer to my desktop: Studio Wildflower. Inside: a moodboard, a rate sheet, the beginnings of a website that looked like it wanted permission to breathe. I renamed a tab: About. I wrote: We believe celebrations should feel like safety and joy in equal measure. We design for the moments that anchor you. We plan the logistics so love can be loud. I sat back, surprised by the steadiness in my fingers. Megan padded in, reading over my shoulder.

“That’s you,” she said.

“It could be.”

“Then make it true.”

“I will.” I swallowed. “But first, court.”

“Court,” she echoed, and kissed the top of my head where the skin had learned how to be skin again.

The arraignment was simply the world agreeing on words. The trial would be the world agreeing what those words meant. In the weeks between, I built a routine that felt like a scaffold: therapy on Tuesdays, PT on Thursdays for the jaw that decided to be interesting about chewing, calls with Victim Services on Fridays to rehearse what happens when you sit in a room with the person who chose to be your harm.

Victoria prepped me like a coach. “Answer only what’s asked,” she said, “and sit with silence like it’s a friend. It’s their job to make you fill it with something they can use. Don’t.”

“What about forgiveness?” I asked once, the word tasting braver than I felt. “People will want it from me.”

“You owe the world safety,” she said. “You do not owe it closure.”

“What do I owe myself?”

“Truth,” she said. “And a future.”

On an ordinary Wednesday, a courier delivered a cardboard evidence box to Victoria’s office; she invited me in because she knows the power of seeing where a story lives when it’s not haunting you. Inside, sealed and bagged, lay the knife. It looked different without the chandelier’s complicity. Smaller. Sadder. A tool that had agreed to play villain because a hand commanded it.

“We’ll give it back to you after,” Victoria said, reading my mind. “If you want it.”

“I don’t,” I said. Then: “Maybe I will. Not to keep. To make into something else.”

Megan squeezed my shoulder. “Unexpected,” she said again, and smiled like she was glad she didn’t know the end of me yet.

The trial date landed on the calendar like thunder with a time stamp. I circled it anyway, a red ring around a day I refused to fear. I placed the Studio Wildflower card on my nightstand where my phone used to sleep, and I let it be the last thing I saw before turning off the lamp.

Part III

On the morning trial began, Denver felt scrubbed. The sky did that January thing where it looks like it could crack if a plane pressed too hard, and the air bit just enough to make you feel awake whether you wanted to or not. Megan parked two blocks from the courthouse because the press had turned the front steps into a coral reef of tripods. She handed me gloves, then took them back and warmed them between her palms before giving them to me again.

“You ready?” she asked.

“No,” I said, and smiled because the truth felt like a superstition that might protect me. “But I’m steady.”

Victoria met us by the metal detectors, her coat immaculate, her briefcase the kind of leather that already knows how trials end. “We do two things today,” she said. “We tell the truth. We don’t let theirs rush us.” She looked at Megan. “You sit behind her left shoulder, aisle seat. That way, when she looks at me, she also catches you at the edge of her eye.”

Inside, the courtroom smelled like wood polish and paper. The ceiling was coffered, the flags behaved, the seal glared down like an old coin. A bailiff told us to take our seats with the voice of someone who knows where quiet lives. The jury filed in, twelve people with lives that had nothing to do with me until suddenly they did. I watched them do the quick math we all do: who has kids, who has a book in their bag, who looks like they wish they’d remembered to feed the cat.

David sat at the defense table in a suit that fit him less than it used to. The orange had been traded for navy by grace of a pre-trial clothing loaner service and a defense attorney who liked optics. He glanced up once, and for a flick of a second I saw the man I’d chosen—charming and straight-backed, the kind of man who talks to servers like they’re people on first dates and says “of course” to aunties who hug too long. Then his eyes hardened into the person who had chosen me for harm. Susan sat behind him, a pale blouse, a delicate necklace, a posture that suggested an apology practicing at the corners of her mouth. When she caught my eye, she tilted her head a fraction. It used to be a cue. Today, it meant nothing.

“All rise,” the bailiff said, and the judge took her bench—black robe, sensible glasses, hair pulled back like clarity itself. She read the case name, confirmed the charges, nodded at the attorneys. The DA stood, a woman in her forties with a voice like a well-tuned instrument.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” she began, “this is a simple case the defense will try to make complicated. You will see a room filled with celebration turn in an instant because of choices. You will hear words that matter. You will watch a video where the defendant chooses a weaponized object and uses it. You will hear a mother attempt to rewrite the moment as an ‘accident’ before there was even time to define it. And you will see Ms. Pierce, who did not choose any of it, do the next right thing over and over: call for help, cooperate, recover, and tell the truth.”

The defense followed with a story I recognized from a thousand dinner fights in other people’s houses: provocation, misunderstanding, “blacking out,” “overwhelmed by emotion,” “pressure of the day,” “a son caught between the two women he loves.” He said the word accident so many times it started to sound like a brand of gum.

Witnesses began like dominoes. The maître d’—measured, precise—described the knife protocol and the moment he heard me fall. The DJ testified about the music that cut mid-bar. A bridesmaid cried, then apologized to the jury for crying, then cried harder. Two servers described my blood in terms that were unpoetic and therefore useful. An aunt who used to like me more than she liked Susan described the tilt of a head and the way David’s hand found the knife with intention, not surprise. The video played twice—once from a guest’s phone, once from a camera the venue had installed to show cake-cuttings on a monitor. The room watched as if rehearsing how to breathe and then remembering.

When it was my turn, the world narrowed to the path from the wooden pew to the witness chair. The oath tasted like ice. Victoria’s questions landed like stones laid into a creek to help you cross: name, age, wedding date, the sequence of ordinary joys, the tilt of a head, the escalation, the knife.

“Did you strike Ms. Cartwright?” she asked.

“No,” I said, because the truth sometimes lets you be brief.

“Did you say anything to provoke Ms. Cartwright?”

“No.”

“Did you hear what she said to the defendant after the strike?”

I nodded once. “She said, ‘Say it was an accident.’ Twice.”

The courtroom took that in like a lung.

“Do you see the person who hit you?” Victoria asked.

I didn’t look at him. I looked at the table in front of me, at the little carved nick in the wood where other trials had snagged their stories. “Yes,” I said.

“Can you identify him for the record?”

“The defendant, David Brown.”

Victoria nodded, then surprised me. “Amanda, how is your head today?”

The defense objected. The judge overruled with a small cut of her hand.

“Scar,” I said, voice steady. “Headaches that come by appointment. Sleep that isn’t a straight line yet. A hesitant jaw if I get cocky with crusty bread.”

“How is your life?”

There was a universe of objection inside that question. None came. Maybe the judge wanted to know, too.

“I go to therapy,” I said. “I make coffee. I work with my lawyer. I practice saying my name like it belongs to me. I founded a company on my kitchen table. I try not to hate my own wedding photos. I’m learning where to put that day in the story.”

“What’s your company called?” Victoria asked, as if we were in a friend’s living room and not a courtroom where a dozen people would measure my grief against a statute.

“Studio Wildflower.”

“What do you do?”

“Events,” I said. “I make celebrations feel like safety and joy in equal parts. I design logistics so love can be loud without having to be brave.”

The defense objected there, late and half-hearted. The judge let it stand. Maybe because she knew juries like to know who they’re deciding about. Maybe because she liked the idea of love not having to be brave.

Cross-examination came in dressed like concern. The defense attorney had a fatherly face he’d probably weaponized his whole career.

“Ms. Pierce,” he began, “is it possible you misread your mother-in-law’s tone after a long, emotional day?”

“No,” I said.

“Is it possible,” he tried again, “that the defendant believed he was… deflecting? That he used the flat of the blade in an attempt to—”

“Protect someone from embarrassment?” I finished for him. “By hitting his wife in front of three hundred people?”

He frowned as if I’d failed to understand a math problem. “Emotions were running high.”

“Mine were,” I said. “So were my guests’. His were choices.”

He shifted to the old reliables. “Have you ever raised your voice to Ms. Cartwright?”

“I’ve raised it to my mirror,” I said. “And to an empty room when I was practicing saying the words ‘your honor’ without crying. To her? No.”

“Did you provoke the defendant?”

“No.”

“Did you belittle him?”

“No.”

He held up a print of a still frame from the video where my mouth is open in a shape that could be misread as disgust but was, in fact, pain. “Is this the face you made at Ms. Cartwright?”

“That’s the face I made when my skull met a knife,” I said. A juror winced. The defense attorney lowered the print as if it had suddenly become heavy.

When they let me step down, my legs remembered how to bend. Megan’s hand met mine before the pew did. “Steady,” she whispered. “Unexpected,” she added, like a benediction.

The DA called the doctor. He said what he needed to with a diagram and a calm that made the jury lean forward. The officer played the audio of Susan’s whisper captured by three different phones: same sentence, same instruction to manufacture story before the blood had dried. Susan’s attorney attempted a salvage—grief, shock, mother’s panic—but grief and shock and panic don’t usually sound like coaching.

The defense put David on the stand on day three. Victoria sat up in a way that told me she’d expected this and also wouldn’t have recommended it if it were her case. He looked at the jury with the face he’d used at charity dinners, the one that says, I, too, donate to the idea of goodness. He told a story about pressure and noise and the way a brain can tilt under lights. He said he reached for the knife without thinking, that he meant to “tap” me, to “stop the moment,” to “defuse.” He used the word “accident” the way a drowning man uses “help.”

The DA’s cross dismantled him with questions that sounded like simple household tools. “You walked to the cake. You selected the box. You opened it. You lifted the knife. You raised your arm. You struck. Your mother did not tell you to put it down. She told you what to say. Correct?”

He faltered on the last word. “I… don’t recall.”

She pressed play on the audio. His mother’s whisper filled the courtroom: Say it was an accident.

He closed his eyes like sound could be a storm you could choose not to get wet in.

“Nothing further,” the DA said.

When closing arguments came, I felt something in the room click into place—not triumph, not relief, but alignment. The DA asked the jury to believe their own eyes and ears and the ordinary laws that keep rooms from turning violent when someone is embarrassed. The defense asked the jury to invent a law in which it was a wedding could be a statute.

The judge’s instructions were careful. She sent them out with a binder of law and a room with coffee. We waited. Waiting is a sport no one trains for. Megan rattled off three trivia facts about Denver’s tunnels. Victoria refreshed her email every five minutes with the restraint of a person you want on your side. I stared at the corner of a framed print, the only crooked thing in the courthouse.

The jury came back before lunch.

“All rise,” the bailiff said, and the jurors looked like people who had taken something seriously and wanted to do it right.

“On the charge of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon,” the foreperson read, “we find the defendant, David Brown, guilty.” The word rang against the wood and returned softer. “On the charge of felony menacing, guilty.” On the misdemeanor count for Susan—incitement and obstruction—guilty.

David’s shoulders did a thing I can’t describe without feeling it in my own. Susan’s hand found his back, then dropped like she’d touched a stove. The judge thanked the jury with sincerity that made me want to bake them all pies. She set sentencing for a month out to give probation time for reports and counsel time for arguments.

“Victim impact statements may be presented at sentencing,” the judge said, looking at me. “If you choose.”

Out on the steps, microphones waited like open mouths. I didn’t stop this time. I did something I had practiced in the mirror when I was supposed to be sleeping: I pulled a small envelope from my coat.

“I have nothing to say about the defendants today,” I said. “I have something to say to the city that held me.” I unfolded a single sheet. “Thank you to the maître d’ who moved when no one knew what to do. To the guests who called. To Officers Daniels and Grant for asking questions that made room for a whole answer. To the paramedics. To the nurses whose hands were kinder than the night. To Dr. Kind-Eyes. To Victoria. To the DA. To the jury. To my friend who is steel wrapped in velvet. This is not a story about a cake knife. It is a story about a room that chose to believe what it saw.”

A reporter blinked like I’d spoken a language that didn’t help ratings. Another whispered “unexpected” to her cameraman and then smiled at me anyway.

Megan looped her arm through mine. “You going to write that down?” she asked, already knowing the answer.

“I already did,” I said, tapping the envelope.

Back at the apartment, we closed the curtains and put our phones face down and made grilled cheese because the body needs rituals that aren’t court-related. The evidence custodian emailed Victoria to say the ceremonial knife could be released after sentencing if I wanted it. I stared at the screen, at the sanitized words—property release—and felt something resolve.

“I’m going to take it,” I said.

Megan looked up, surprised but not arguing. “To do what?”

“To make it hold something else,” I said. “Melt it. Hammer it. Turn it into door handles for the shelter kitchen. Into a bracket for a bench in the women’s clinic waiting room. Into something that isn’t a story about harm.”

“Unexpected,” she said for the third time that day.

“At sentencing,” I said, the idea building out loud, “I’m going to ask the court for two things: a permanent protective order—and permission to repurpose the weapon into something that opens instead of shuts.”

Victoria called an hour later. “I like your idea,” she said. “It doesn’t help or hurt the sentencing guidelines, but it tells the room what kind of person you’re building yourself into. Judges remember that sort of thing.”

“Do you think it’s… too soft?” I asked, the old fear creaking like a door I still checked twice.

“I think it’s sharp in a way the law respects,” she said. “We’ll draft a motion. You’ll own the words.”

That night, I set the Studio Wildflower card on my nightstand again, only now I tucked something under it: a photocopy of the docket with the word Guilty circled in red. Two weights. Two kinds of paper. Both true. I turned off the lamp. The scar near my hairline itched where new skin negotiated with old. In the quiet, I heard the judge’s voice again: Victim impact may be presented if you choose.

I chose.

Part IV — Victim, Voice, Verdict (≈1,600 words)

Sentencing day smelled like snow. Denver had worn blue for trial; now it showed up in a clean gray suit, clouds low and patient above the courthouse. Megan parked us in the same lot two blocks away and tucked a hand-warmer into my palm the way mothers tuck lint out of sight before pictures.

“You’ve got your pages?” she asked.

“In triplicate,” I said, patting my bag. My victim impact statement lived in a folder beside a motion Victoria drafted: Petition to Repurpose Seized Evidence for Community Use. We’d attached a letter from Safe Harbor—our local women’s shelter—confirming they would gratefully accept the metal, melted and recast as door handles for their kitchen and family room. A welder had signed on pro bono. We had lined up chain-of-custody logistics as if we were coordinating a small moon landing.

Inside, the courtroom was the same and different. The jury seats were empty; the gallery held a pared-down audience: a couple of reporters, three law clerks, two women I didn’t know who gave me the kind of nod strangers give when they’ve read your name in a story and want to say you’re not a headline to me. Victoria met us with that precise, warming smile she saves for days when the law becomes a human.

“DA’s asking for eight,” she said quietly. “With a mandatory minimum served. For Susan, four—part suspended, the rest in custody and probation with conditions.” She lifted a brow. “You still want to do the repurpose request today?”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s the point. I don’t want the last thing the knife does in this world to be what it already did.”

We sat. The bailiff called the court to order. David was brought in from lock-up in a suit again, thinner than last month, anger tucked away like a weapon he couldn’t get through security. Susan took her place behind him in a modest dress that spoke fluent optics. The judge reviewed pre-sentence reports without performative drama. She called the DA; he spoke in terms I’ve learned to respect: facts, statutes, the way community safety is not just a phrase for editorials.

“Your honor,” he concluded, “this was public violence. The defendant’s mother attempted to shape narrative before aid. The victim’s recovery is ongoing. We ask the court to impose a sentence that reflects harm, deterrence, and protection.”

David’s attorney tried to make a second life for the word remorse. He said pressure one more time, blacked out one more time, then first offense like he was telling a story that could be contained in a file folder. He gestured toward the gallery where exactly three people sat like props.

The judge nodded, then looked at me. “Ms. Pierce, would you like to be heard?”

I stood, pages in hand, and walked to the lectern. The wood had a notch at the edge I hadn’t noticed during trial. I rested my finger there to keep from curling my hand into a fist.

“Thank you, your honor,” I began. My voice sounded like it belonged to me. “I’m not going to re-litigate what happened. You have the video, the medical reports, the testimony. You saw the room choose. I want to tell you what those minutes have done to the hours since.

“I have a scar at my hairline. It’s small. It isn’t the injury that interrupts my days most. The headaches come on their own calendar; sleep keeps a second set of books. For weeks, I couldn’t cross a kitchen with a knife block on the counter without my lungs making a decision I didn’t approve. The first time a champagne cork popped in a restaurant, I was under the table before I realized I’d moved.

“I am also not only a person with a wound. I went to therapy. I accepted help until accepting help felt like strength and not like failure. I founded a small business at my kitchen table with a friend who turned out to be a network of arteries I didn’t know I had. I wrote a sentence that says we design logistics so love can be loud, and I mean it. I am building a life that isn’t a rebuttal—just a life.

“I’m asking for two things today. The first is safety on paper: a permanent protective order that recognizes reality. I should not have to calibrate my mornings around whether I’ll share sidewalk air with the man who raised his hand to me or with the woman who tried to rename what he did. The second is permission to move the story forward in metal. The ceremonial knife was a tool until a hand made it a weapon. I’m asking the court to release it to Victim Services so it can be transferred to a welder who will melt it and recast it into door hardware at Safe Harbor. I’d like to turn the thing that shut something in me into something that opens for someone else.”

I lifted my eyes. David watched with a face that was part confusion, part insulted. Susan stared at the table as if one knot in the grain might take her away.

“I’m not here to forgive,” I finished. “I’m here to live. Sentencing doesn’t change my scar. But the law can change what my city holds me with. Thank you.”

The judge looked at me for the full measure of two breaths. “Thank you, Ms. Pierce.” She turned to the defense table. “Mr. Brown? Ms. Cartwright? Do you wish to be heard?”

David stood, and for a moment I thought he might attempt an apology that sounded like a weather report. He said instead, “I lost my head. I’m sorry she got hurt.” The sentence worked hard to avoid naming the actor in its own clause. The judge’s mouth did a thing I recognized from the faces of women who have to remain professional more than men do.

Susan stood next, gripped the back of David’s chair as if furniture could be character witness, and said, “I was… distraught. I did not intend harm. I am a mother.” The word mother landed in the room like a foreign noun no one had evaluated for meaning.

The judge folded her hands. “This court isn’t in the business of adjudicating your identities,” she said. “Only your choices.”

She recited the law, then imposed sentence: eight years for David, with a mandatory minimum served and post-release supervision; four years for Susan, half suspended, the balance in custody and probation with conditions that sounded like the bones of accountability. She granted my permanent protective order without a sermon. Then she did something I hadn’t expected—maybe because I’ve spent too long expecting only the least from rooms like this.

“Regarding the victim’s request,” she said, tapping Victoria’s motion, “the court appreciates the creativity and symbolism. The clerk will coordinate with DPD Property. Upon completion of the appeals window, the court will direct the ceremonial knife, catalog number 23-1947-E, be released to Victim Services for transport to the named fabricator. The court loves a good door.” Laughter moved through the courtroom, surprise-soft and grateful. “Ms. Pierce, when the handles are installed, someone from chambers would like to attend.”

I blinked. “Yes, your honor.”

“Court is adjourned.”

The gavel struck. It didn’t sound like thunder. It sounded like a clean close to a meeting that mattered.

On the steps, cameras waited, but not like a reef. Like a few curious birds. I read the same sentence I’d read after trial and added a new one. “A judge said yes to turning a weapon into a handle,” I said. “That feels like a city deciding what it wants to be.”

Megan hugged me so hard my teeth clicked. “You did that,” she said into my hair.

“We did that,” I said back into hers.

Divorce court plays in grayscale after criminal court’s color. No jury. No exhibits that make a room gasp. Just a judge with sleeves metaphorically rolled, a Zoom monitor where an orange jumpsuit framed David’s face, and Victoria walking me through the ordinary miracle of being untied on paper.

“Do you contest this divorce?” the judge asked David.

He glanced at the camera, then down. “No.”

“Permanent protective order is continued,” the judge said, clicking her pen like punctuation. “This marriage is dissolved. Ms. Pierce, you owe Ms. Cartwright nothing, and Ms. Cartwright owes you nothing except obedience to the orders of this court.”

I walked out of that courtroom lighter by pounds you can’t count. The Denver air tasted like it belonged in my lungs.

The knife moved through the world like contraband and hope. A detective I’d never met signed it out of the property room with a witness present. He carried the evidence case like a violin and set it on the welder’s steel table with reverence that made the metal shop feel like a church. The welder—Jorge Morales, silver hair tucked under a cap, hands like a map of work—nodded to me and then to the detective.

“You sure?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

He set the blade on a bed of flux, dialed the torch, and the room filled with a white roar I felt in my ribs. The knife’s mirror finish turned to orange, then to a soft glowing that made it look almost kind before it slumped. He guided the melt into a mold we’d designed—the curve of a hand, the weight just right. Later he would grind and drill, sand and seal. But in that moment, it was enough to watch what had once been chosen as a tool for harm choose not to be that anymore.

“Want to try?” Jorge asked once the flames were down. He handed me a hammer and pointed to a small tab of still-warm metal destined to become a hidden bracket. I swung. The tap rang high and then low. The sound felt like agency.

“Unexpected,” Megan whispered, eyes wet, and laughed at herself. “I’m going to get this word printed on a plaque.”

Installation day at Safe Harbor landed on a Saturday with sun. Women in maintenance uniforms met us at the back door, cordless drills in holsters like they were finally starring in their own show. The handles gleamed under the porch light, the grain of the newly cast metal catching the morning like a promise. The judge showed up in jeans and a baseball cap. Officer Daniels came off-shift and brought donuts to the kind of ribbon-cutting where the ribbon is a strip of tape you tear with your hand and smile anyway.

We passed the handles around before they went on—cool, substantial, not a bit of their old life left except for the engraving we asked Jorge to set on the underside where only install crew and future curious hands would find it: OPEN.

“You want to do the first door?” a maintenance lead asked. Her name tag read Tai. Her face read No one tells me how strong I am before I do.

“Yes,” I said.

I placed the handle into the bracket, lined up the screw, and tightened until the head sat flush. When I pulled, the door swung open on hinges that didn’t squeal. The room beyond was bright. Someone had already set a stack of plates on the counter as if inviting the metal to have a meal like a citizen.

The judge stepped close. “I meant what I said,” she told me quietly. “Court loves a good door.”

“We do, too,” Tai said, one hand on her hip, the other on a drill. “We love it when they open.”

We ate donuts on the shelter’s back steps. Megan bumped my shoulder. “What’s next?” she asked, eyes aiming past the parking lot into the type of distance you can fold into your pocket and carry.

“Clients,” I said. “Calendars. Flowers. Checklists. A fire marshal on speed-dial. And—” I tapped the handle with one fingertip—“the right kind of hardware.”

“Unexpected,” she said, and we laughed because joy should get to be a running joke.

To be continued…

Part V

Spring found Denver with a sense of humor—snow one morning, sun by lunch, a wind at dinner that flipped patio umbrellas like cards. Studio Wildflower bloomed in a corner of my apartment that I rebranded as an office by adding a plant and a whiteboard. Our first paid event was a corporate dinner in LoDo that wanted something elegant that doesn’t feel like trying too hard. I made candles.

We said yes to everything we could do well: a teacher retirement at a brewery, a fiftieth anniversary under string lights, a baby shower where the mom-to-be cried because we hung photos of everyone in the room at the age of one. When a bride asked me—tentatively, apology already loaded—if I would take on her wedding given, you know, the thing, I told her the truth: “I plan celebrations because I know exactly what they have to hold.”

Word spread the way it does when you do the ordinary things right. Vendors answered our calls on the first ring. Caterers didn’t add a surcharge for last-minute stubbornness. A DJ texted Megan mid-reception to tell her our timeline was chef’s kiss, and she printed it and taped it above the desk like scripture.

The handle project turned into gravity. Photos of the Safe Harbor install made their way onto the shelter’s newsletter, then into an annual report, then into a local paper’s feature on restorative art. A hospital clinic called to ask if we had any metal left. We didn’t—but Jorge had a workshop, and I had a new circle of donors who understood what it looks like when a city decides its symbols should be useful.

On a Tuesday when the sky couldn’t remember what color it wanted to be, I got a text from the courthouse number saved in my phone as Chambers: If you’re free at 10, a new intern is giving her first tour. She wants to include “the door story.” I went. The intern—twenty-two, unstoppable—told a group of high schoolers about evidence and outcomes and how justice sometimes looks like a handle that opens to a kitchen where no one yells. One of the kids raised his hand and asked if the metal remembers. The intern said, “We do.”

On a Thursday, I met with Victim Services to talk about a pilot program: Ritual & Repair. When a case closes, if the survivor wants, we’d help create one tangible transformation—metal to hardware, fabric to quilts, paper to seed bombs you can throw into empty lots and turn into wildflowers. I sketched a logo on a napkin. Megan made it beautiful. The DA promised to convene a working group with more acronyms than sense. It didn’t matter. We had a map. Paper would help.

On a Friday, I drove past the wedding venue for the first time on purpose. The chandeliers were still there; the staff was new. I sat in my car across the street and let my chest do its old routine and then finish it. I texted Megan: I’m okay. She texted back a GIF of a door that opens onto a field of ridiculous tulips. I laughed, alone in my car, and didn’t feel alone.

On a Saturday, we did what Studio Wildflower was built to do: we made a room steady enough for joy to be loud. Emma and Nate wanted a library wedding because their love started between shelves. We built an aisle out of first editions and borrowed paperweights shaped like birds. We wrote the schedule in the same font as old card catalogs. We ran the rehearsal twice because Emma’s dad teared up the first time and got everyone off count.

During setup, I found myself behind the cake table, adjusting the runner so it fell in a clean line. The baker’s assistant slid a knife onto the satin next to the cake. It was ordinary, stainless steel, a rental. My hand hovered, then landed, then moved away. No vertigo. No kaleidoscope behind the eyes. Just a tool on a table in a room that had been entrusted to me.

Emma found me there and took my hand. “You good?” she asked, because good brides know their vendors are humans.

“I am,” I said. “Do you want me to walk you through the cutting? Two hands, slow, look up for the camera every second slice, napkin at your elbow.”

She laughed. “You think of everything.”

“That’s my job,” I said. “Official planner, unofficial fixer of all things.”

She squeezed my fingers. “If anything feels off, I’ll look for you.”

The words landed like an echo from a night that had tried to rename me. I let them be what they were now: trust handed back to the right person.

The ceremony was good on a cellular level—vows you believed and crowd laughter that didn’t need to be prompted. When the moment came, we did the cake tableau like choreography. Emma reached for the handle. Nate covered her hand with his. They cut through buttercream while cameras clicked and everybody cheered. I stood to the side and watched a room be what rooms should be when people gather to say this is us and we mean it.

Later that night, when the DJ hit the lights and the staff rolled out the mops, I sat with Megan on the steps out back and let our feet recover their opinions. The skyline threw back a thousand windows of light. A train horn stitched a straight line through the air.

“What’s our ending?” she asked softly. She doesn’t mean the business. She means the story we’ve been telling with our days.

“This,” I said. “Not the night that cracked open. The one we built to hold.”

She tilted her head. “Unexpected,” she said, because of course she did. “You know you made that word mean something new.”

“So did you,” I said.

We packed the van with the last crates and drove home with the windows cracked because April in Colorado is good at pretending it’s June after midnight. In the apartment, I pinned one more thank-you note on the corkboard—this one with a drawing Emma’s niece had made of two birds holding a tiny banner that said YES. I taped the photo from Safe Harbor next to it—Tai’s hand on the door, her grin aimed at the camera like she’d just dared the world to try to close it again.

Before bed, I stood at the kitchen cabinet and touched the emancipation-within-myself paper I keep taped there: the protective order; the court order authorizing the repurpose; a receipt stamped PAID from the welder that he refused to let me pay and that I insisted on covering anyway because dignity is not a charity. Behind them, a business license for Studio Wildflower. On the shelf, a stack of white envelopes with OPEN stamped in green where a return address would be—thank-you notes we send to vendors when they do the small things that keep the big things together.

My phone buzzed. A number I don’t like but no longer dread. The prison system’s automated line handed me a recorded message: This is a call from an inmate… I let it expire. I do not answer doors that don’t belong to me.

I texted Victoria a picture of the handle with the engraving. If another judge wants a door, we’ll make one, I wrote. She sent back a gavel emoji, then: Court loves a trend.

I turned off the lights. The apartment did the gentle inventory of a place that forgives you for leaving dishes until morning. The scar at my hairline ticked once like a clock resetting itself and went quiet. In the dark, I pictured Safe Harbor’s kitchen—hands on metal that used to harm, now opening their way to coffee and casseroles and the daily work of staying.

There is no music swell and fade-out in real life. There is the sound of your own breath finding its ordinary tempo. There is a front door you lock twice because you’re careful, and a back door you leave propped because your friend is carrying in flowers, and the knowledge that, if smoke ever comes again, you know how to move through it and put it out—and then build where the fire thought it would live.

The headlines shrank. The calls stopped. The handles stayed cool under a hundred hands. Studio Wildflower’s calendar filled in squares that used to be blank. Megan started saying we in emails without a second thought—we can do that; we’ve got you; we’ll be there at nine—and every time she did, something in my ribs sat down where it belonged.

On an evening when the Rockies held the last light like a tablecloth you don’t want to shake just yet, I drove out past the city to a field and watched the sky change its mind six times. I thought about the girl in white counting chandelier stars and the woman who stood beneath courthouse fluorescents and asked a judge for a door. I thought about the people whose names I learned because they stood between me and a worse night. I thought about the way Megan’s voice sounds when she says my name like a reminder. I thought about how I responded when the worst version of love took action: not by playing their scene, but by writing another one and getting enough people to say their lines.

I drove home and parked and let myself in with a key that can’t be revoked. On the kitchen wall, our schedule for the week smiled in dry-erase ink: Tuesday—vendor walkthrough; Wednesday—flowers; Thursday—harbor meeting; Friday—rehearsal; Saturday—wedding; Sunday—rest. I wrote one more word under Sunday in smaller letters, a promise you make to yourself when no one is looking.

Open.

And that’s the whole of it: my wedding day, my mother-in-law’s slander, the moment my husband chose the ugliest action—met not with a matching ugliness, but with a choice they did not expect. I built a door. I walked through it. I hold it for others when their hands shake. The end isn’t thunder. It’s a latch you can lift.

It’s me.

THE END

News

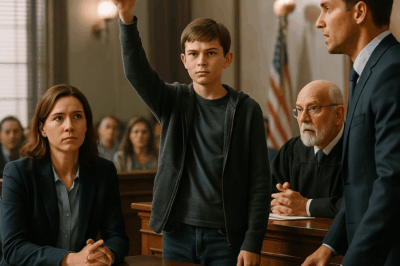

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load