Part I

The autumn that took my father arrived on the wind in gold and fire, rimmed in the kind of beauty you only notice when you’re twelve and you’re sure the world is built for you. In Riverside, Michigan, leaves fluttered down like lazy applause along the streets of two-story colonials, and our white picket fence stood up straighter than the rest, a smile drawn in boards and nails. I thought that fence meant something. I thought it was a promise.

We lived in the kind of house advertisers dream about—scented with cinnamon and vanilla most days, warmed by an oven that always seemed to have some sweet ambition inside, a place where the floorboards creaked in familiar rhythms and the kitchen table caught every sunbeam that dared to come near. My dad, Robert Carter, would sit across from me at that table with a pencil behind his ear, patient as the lake, promising that fractions had nothing on me. He solved the unsolvable by leaning closer and saying, “Take it one step at a time, kiddo. Everything is just the next little step.”

He worked nights sometimes at the auto plant and had gentle brown eyes that wrinkled like folded paper when he smiled. He smelled like motor oil and Ivory soap, and he would sneak a cookie when Mom wasn’t looking, winking at me like we were co-conspirators in a harmless heist. On weekends, he’d roll the Mustang out like a sleeping dragon, and I’d hand him tools with fingers too small for wrenches. We lived in an orbit that held steady and bright.

My mother, Linda, taught third grade and sang while she cooked. Off-key, loud, unconcerned. She had a knack for pancakes shaped like Mickey Mouse and buying too many tomatoes at the farmers’ market. On Friday nights we watched movies in a tangle on the couch; on Sunday we had pancakes that looked like cartoons; and on any evening in between, there was the sound of my mother’s laugh bouncing off the walls. I believed that laugh could raise the dead.

Then came the Tuesday that split my life clean in two. The principal’s voice called me to the office and I walked a hallway that didn’t seem quite level anymore. A semi jackknifed in the rain on Route 23, they said. The phrase had edges. They promised he didn’t suffer, as if that mattered, as if pain were the only thing to fear. Pain ends. Absence endures.

The funeral was a mosaic of wet grass, black coats, casseroles, and quiet brutality. I remember the taste of metal in the cold air. Mom stood like a person who’d been poured into herself and left to harden—no tears, no sound—until nights came and the walls went thin. Then I heard her sob into Dad’s pillow, calling his name as if she could coax him out of the ground.

What people don’t tell you about grief is that it’s work. It is heavy, repetitive labor. It’s hauling buckets of “do the next thing” up the stairs of your own ruined house. We tried. The house did not help. The house remembered him.

Bills replaced recipes on the kitchen table. Dad’s coffee mug loitered on his desk like a bad ghost. The savings evaporated in neat, official withdrawals. Mom’s melodic life narrowed to a series of small, blurred movements. She took a leave from school that grew and grew. Her body was there, but the pilot light had gone out. I forged permission slips because the world kept asking for signatures and nobody was around to sign. I leaned on the internet to learn how to boil pasta and brown meat and unstop a drain. I found out you can keep a house running from the passenger seat if you memorize the controls.

A guidance counselor—bless those human barometers—smelled the storm and kept pressing, but I lied like a champion. I told her the thing adults wanted to hear: We’re adjusting. It’s been hard. We appreciate your concern. I told her because if I didn’t, the state would come sniffing around with clipboards and flashlights, and I couldn’t lose anyone else. Not again. Not ever.

Two years went by like slow animals dragging broken legs. I turned fourteen in a body that looked like it was still thinking about being a child, confused by its instructions. The soft parts sharpened. My mom returned to her classroom with a dove-gray face and a voice that skimmed the surface of the day. The house became a museum of a family that had gone off to war and never come back. We were a two-person reenactment, slow and careful, going through motions for a crowd that never arrived.

It would have gone on like that—like a plant that lives on dew and nerve—if Mrs. Henderson from next door hadn’t decided our gutters were a scandal. She sent a contractor named Frank to fix what sagged. My mother gave him coffee because she was raised to see a stranger on a ladder and think “Can I get you something?” This is how stories begin: a small kindness. A favor. A man with ice-blue eyes who set a heavy hand in our kitchen and did not take it away.

Frank was broad across the chest, all work boots and flannel, hair dark as a bruise with a line of gray that said he’d had to fight a thing or two. His nose bent left like it had been persuaded by a fist. He laughed the way some men laugh around widows—too hard, too long, the way you laugh when you’re trying to sell a broken truck as “classic.” He smelled like cigarettes and something tangy that I later learned was beer in the afternoon. He had a way of taking space as if the space had been expecting him.

He came back to patch the roof. He came back to fix the fence. He came back to look at the furnace, because it was getting cold and “a man ought to check a furnace for the women.” He brought groceries as if they were the currency of decency. He refused payment because “neighbors help neighbors.” Our living room filled with the heat of his voice, and for the first time in two years, Mom hummed while she folded towels. He gave her the gift of ordinary conversation in a kitchen that only knew silence.

Six months later, he brought a suit to the courthouse and a ring to my mother. I wore a new dress that felt like a lie I wanted to believe. Mom cried quietly in the county clerk’s office and called it joy. Frank slid a hand around her waist and called it love. We drove home in his truck like three people who trusted the bridge.

The honeymoon lasted exactly three weeks. It is a credit to Frank that he didn’t rush it. He let the sweetness cure, like varnish, and then set the furniture of our lives in a new order. He began with small criticisms delivered with a smile—her cooking was too salty, her skirt too long, the mail “poorly organized.” Suggestions turned into rules with the frequency of a light set to a slow strobe.

Dad’s study became his man cave. My father’s glasses disappeared from the nightstand. The coffee mug vanished from the desk. One morning, I came home from school to find a box of my father’s papers shoved into the garage—mildew already licking the edges of the past. When Mom protested, Frank punished the air with silence until it bent around him. Apologies became a new kind of currency, and my mother printed them like money in a panic economy.

He folded himself into our finances with the ease of a man who had read a manual. “We’re married now,” he told Mom, “no sense in keeping your little accounts separate.” He put his name on things because “what’s yours is mine.” He handed out allowances and said it with a smile so the insult sounded like candy. “You can keep your little job,” he said, as if allowing a child to play at work. He had ideas about her friends. He had opinions about mine. His opinions had consequences.

He cranked the thermostat down and the criticism up. He found a way to sound generous while pushing my future off the table. When acceptance letters started arriving, he rerouted them to the trash. I learned to have my mail sent to a friend’s house. Frank learned how to stand on a porch and sell parents a nightmare they hadn’t considered—that their daughter was testing boundaries, that I was bad influence, that it was safer for everyone if I didn’t come around.

He was a chameleon. He was sunshine for company, a storm when the door closed. He could hand a neighbor a beer and call me an ungrateful girl without taking a breath. He told me I should be grateful—a charity case on legs. “No man would take on another man’s kid,” he said, and added “and debts,” because he liked to drape morality over greed like a clean sheet over a stained bed.

Underneath all that theater, there was math: one woman’s grief multiplied by a man’s hunger for control. You can call it charisma. You can call it a gift for reading rooms. You can call it what it is: predation with good posture.

Around the time I learned to fold myself small, Ms. Jacobs—the guidance counselor—offered a ladder. She asked questions that made the walls of my skull echo. She said the word “independence” and let it hang in the air like a rope dropped through a trapdoor. She talked about the Army like a real place where the rules were visible and consistent, where mornings began with a time and a trumpet instead of dread. She slid me a brochure showing a girl who looked strong in a uniform that fit like purpose. I took it home and slept with it in my pillowcase like a talisman. I turned pages in the dark, and each photograph let in a little light.

My mother didn’t ask why I started spending extra time at school. She had learned not to ask questions that could turn into fights. I learned to forge her signature, a skill already polished by necessity. Sergeant Williams—the recruiter with eyes that kept their promises—looked at me like she could see the outline of my future on my face. “Why?” she asked, and I offered patriotism because it sounded better than “I want a life where no one controls the light switch but me.” She smiled, a line of mercy in a hard world. “That’s a real answer,” she said.

I built my exit like a bridge in the fog: step by step, test by test, lie by necessary lie. The date circled itself in my calendar—July fifteenth—and I started measuring time in quiet triumphs. Frank sensed the change the way animals sense weather. He went through my room and found a bus ticket that wasn’t supposed to exist. He cornered me in the kitchen and tried to make the air go thin. “You’re not going to the military,” he said, as if the word “not” had magical power. I told him a truth that tasted like copper. “I am leaving.”

He turned to my mother and asked her to choose. She chose him. It was the kind of cut that doesn’t bleed until later, when you’re alone, and you touch it and say there’s nothing really wrong. I pretended I didn’t feel it. I learned to pretend like a professional.

On July fifteenth I left before dawn. I left without notes or explanations. The house watched me go the way houses do—doors and windows holding their breath. I pulled an old promise around me like armor: never again. It was a child’s oath. It was mine.

Basic training met me like a wall and then taught me to climb it. The Army took the trembling at the center of me and gave it a job. Four a.m. wakeups and shouted orders were a choir compared to Frank’s arbitrary storms. I learned to stack tools inside my body—discipline, endurance, the ability to live inside the next breath and not negotiate with pain. I learned that I could look someone in the eye and say “No” and the world would not end.

There’s a moment in every new life when you understand you are no longer who you were. Mine came with a drill sergeant’s voice in my ear—“Two minutes, Carter, fix it”—and hands that moved faster than fear. I folded sheets so tight they hummed, and somewhere in the middle of all that precision, I found a part of myself that Frank had never laid a finger on.

I didn’t know it then, but the war I thought I’d left behind had not finished with me. You can leave a house. A house can follow you. Some ghosts get on planes. Some promises boomerang. And sometimes the fight you ran from waits in a basement for your return with a smile so wrong it could freeze the air.

But before all that, before the crack of metal on bone and the hiss of gas and the rattle of a lock sliding home, there was the quiet, clean happiness of a girl learning she could build herself stronger than her fear. For a while, that was enough.

For a while, it was everything.

Part II

Fort Jackson was a furnace that burned weakness into smoke. My body joined the assembly line that turns civilians into soldiers—shaved time into units of discipline, stacked days like ammo. I learned the names of new muscles because they talked back each morning. I learned what fear feels like when it doesn’t win.

During combatives, a redhead from Texas named Sarah Bennett put me on the mat so fast I thought I’d slipped. “You fight like you’re trying not to hurt anyone,” she said, offering a hand. “That’s a great way to get dead.” The ring lights made circles in her eyes. I told her I didn’t want to hurt anyone. “Sometimes you hurt people so you can keep breathing,” she told me like it was a basic fact, like the sky is blue and a chokehold is a method of persuasion. “Want me to show you?” She taught me balance and leverage and the art of making space where there wasn’t any—on the mat and in my life.

We graduated and moved to Fort Gordon for intelligence training. I had the ASVAB scores to point me toward the rooms where maps float and screens glow in the soft blue that says secrets are being kept. My brain loved the puzzles—patterns that didn’t show themselves until you ran them again at an angle, sideways, through another data set. I learned to see the world like the back of a tapestry. Threads that looked random on a surface made a threat or a solution when viewed from behind.

Sarah went communication. We met at chow and compared notes like kids comparing scars. When we could, we split cheap pizza and planned out loud like two people who believed the future would hold still long enough for our hands. “Germany,” she said, doodling a little castle on a napkin. “Or Hawaii,” I said, but really I meant “anywhere not Michigan.” We got Fort Campbell, Kentucky. I took it like a lottery win.

As a junior analyst, I built threat models and learned the new grammar of war. I counted things and told other people what they meant. The job was numbers and nuance and quiet—the silence inside headphones broken by the occasional “copy” when you guessed right. In my off hours I took online classes, shredding gen ed requirements like paper and stacking credits like bricks in a new house I was building inside my head. If I had to walk away from everything, I wanted to be carrying something.

Money piled up the way money does when you’ve never had any and the Army feeds you, houses you, and pays you to wake up. I didn’t buy anything I couldn’t fit into a duffel. The idea of owning furniture felt like tying myself to the ground with ropes. I bought a good pair of running shoes. I sent no money home. I checked my bank balance like a person checking a fever—am I safe yet?

At first, my mother’s emails were polite little weather reports. “Hope you’re well. The dogwood bloomed. I baked cookies for the bake sale.” Then they came less often and hurt more. “Frank lost his job. He’s stressed,” and “We’re fine, we’re fine,” and “The roof is leaking again,” in case I’d forgotten what roofs do. Occasionally she called. She would ring late, quick, always when Frank was at work or at a bar or gone in that way men go when they want to make you ask questions. She kept the calls short, her breath shallow in my ear. “How are you?” “Busy.” “Are you eating?” “Yes.” There was no real vocabulary for what we had become to each other: a pair of women with a cliff between them.

The lies she told to keep from drowning became a second skin; sometimes I thought she wore them to bed. Once, I caught a sound in the background of a call—a noise that was all sharp corners—and then Frank’s voice: “Who are you on the phone with?” The line went dead. I stared at the wall and felt my throat go tight. In the gym, I beat a heavy bag until the wraps went red and a sergeant told me to knock it off or he’d write me up for bleeding on equipment.

Sarah slid into the quiet next to me like a practiced habit. “What’s the weather in Riverside?” she asked without asking. “Storms,” I said. “Well,” she answered, “you’re the one who reads radar for a living.” That’s the thing about friends who become your family: they say impossible things and expect you to make them true.

Then Mrs. Henderson—our book-club neighbor with a surveillance talent—sent photos through a mutual friend’s Facebook. My mother in July, wearing long sleeves and an expression that looked like a bruise. A whisper of purple at her collar. I did something I was trained not to do: I called the enemy directly. Frank answered. “She doesn’t want to talk to you,” he said, and hung up the world.

I put my phone through a wall. The next morning, I wrote the check to replace government quarters with a cheap off-base apartment so I could hang drywall at my own pace.

When you are a soldier, you deal in contingencies. When you are a daughter, you deal in hope. I thought I could graft one over the other: contingency hope, hope with a plan, hope that had weight. For months I kept a bag packed under my bed, sat at the edge of sleep like a sentinel waiting for a text that said, “Come.” None came.

The knock came at two a.m. instead.

I woke to the sound of someone trying to pound my door off its hinges. My hand went for my service pistol as if a string had tugged it. Through the peephole, I saw him—older, thicker, angrier—and my mother behind him like a smudge. I opened the door not because I wanted him in my space but because I knew how to stage a scene when you might need witnesses, how to make a report clean. “Military police are on their way,” I lied. The wind swung in behind them and scrolled the curtains across my living room like ghosts.

Frank paced like something had borrowed his skin. “You poisoned her,” he said, jerking a thumb at my mother. “You come around here, fill her head with leaving, and look what happens. She gets ideas.” The word “ideas” with a clenched jaw is a kind of confession. He didn’t want a wife. He wanted a congregation.

I looked at my mother and said her name. Her eyes were wet glass, reflecting someone she didn’t recognize. “Do you want to go home?” I asked. Frank answered for her. “She’s my wife.” I asked again, the voice I use to read coordinates. She blinked twice, slow, like a secret code on a sinking ship. I stepped between them and saw the bulge under his jacket—the familiar outline of a bad decision.

He came fast, faster than I remembered, and the next thirty seconds were a math problem: solve for X where X is the distance between your throat and his hands. The coffee table exploded. The knife appeared like a trick of light, then made its case across my forearm. I found his wrist and bent it until gravity did the rest. A chokehold was a story with a clear ending. Part of me wanted to write it to the last period. Sirens put punctuation on the night. I let him go.

Base hospital. Twelve stitches. Forms on a clipboard. My mother refusing to press charges for anything that had happened inside that house back home. It is an art to refuse to save yourself so beautifully the police almost applaud. “He didn’t hurt me,” she told a patient female officer in a tone that made truth call to say it wasn’t feeling well. “He never has.” The officer didn’t argue. You don’t argue with people who’ve rearranged reality so it sits comfortably on the couch.

The next day, my CO sat me down and spoke the language of chain of command and liability. “If he returns,” he said, with a kind of careful emphasis that meant, please do not make me have this conversation again, “the Army will handle it.” He slid a paper across the desk that looked like a restraining order. The ink smelled new. “Don’t give him a second act,” he said.

From my apartment window that afternoon, I watched my mother load a man into a car like he was fragile cargo. He turned his head and found my eyes and smiled—so small and private it might have been a twitch. Sarah sat on the edge of my coffee table like someone willing it back together with posture. “He’s going to escalate,” she said. “Abusers always do when someone turns on the light.” I told her I was done playing defense. She asked me if I understood what offense costs.

The preliminary hearing came like a buzzsaw and left like one, too. Frank wore respectability like a rental suit and let a lawyer earn his money. My mother’s testimony cut me seventeen different ways and salted every cut. She lied so gracefully I almost stood up to applaud. The charges got small enough to carry and the judge put them in Frank’s pocket along with a restraining order that twisted toward me. If irony were a person, it would’ve clapped me on the back and bought me a drink.

Frank’s parting line in the courthouse hallway was scripture delivered to a congregation of one. “You came after my family,” he said, meaning himself in the plural as men like him do. “Now I’m coming after yours.” I didn’t think about who “yours” meant until the email came two weeks later, neat as a postcard, sent from my mother’s account: I’m leaving him. Come help me pack. Tonight at ten. Come in the back. Don’t tell anyone. He has people watching.

It read like a man had written it on his way out the door. But what if. What if this was the crack in the wall. What if this was the ladder lowered down the well. Sarah found me staring at the screen. “It’s a trap,” she said, the way she might say “it’s raining,” or “that road is out.” I told her about the one-percent chance that changes everything. We agreed to go—but we didn’t agree to be stupid.

We told the MPs where we were heading. We documented what could be documented. We put spare batteries in the flashlights and gas in the car of the friend who had become the kind of family you earn. We drove toward a house that had once smelled like cinnamon and now smelled like something else entirely: a plan.

By the time we rolled past the white picket fence, the night had the wrong temperature. The only light glowing came from the small basement window in back. Sarah asked the question I should have asked first: “Why would she be in the basement?”

Because that’s where the story ended the first time. Because that’s where he was strongest. Because predators return to the scene for the same reason saints return to altars.

I heard my mother’s voice—the frayed ribbon of it—asking for help. It sounded like a miracle until you noticed the timing. I ran anyway, because daughters run toward mothers calling for help, even when they are soldiers, even when they have read the script. The back door opened without a key. The stairs down smelled like that dream where you’re underwater and you remember you never learned to swim. The bulb was a single failing star. My mother stood in the corner smiling the way a mask smiles.

The door closed behind us. The lock slid home. Frank stepped from behind the water heater holding a bat like a baseball game with no crowd. I smelled it then: the hiss and whisper of natural gas flooding a room.

Some nights don’t ask for a plan. They demand an exit.

Part III

You never notice how loud silence is until you’re locked in with it. The basement in Riverside was cinder block and memory, a low ceiling that made even breathing feel tall. The single bulb hung on a frayed cord that had seen a dozen Christmases, and the air, God, the air—sweet and wrong with the metallic edge of something meant to heat a house now rehearsing for a tragedy.

Frank’s smile curled like old paint. He didn’t bother with a speech at first. He didn’t need one. The room was talking for him—the hiss behind his shoulder, the sharpened light, the way my mother sat aside like a piece of furniture that regretted being in the picture. When he did speak, his words were practical, like a foreman explaining a safety protocol. “You’re going to attack,” he said, weighing the bat in his hands. “I’m going to defend my home. We’re all going to be real sorry about the gas line. Shame about old houses. Faulty ventilation. There will be… condolences.”

“We’ll die too,” I said, just to draw a line on the map. He laughed and gestured toward the stairs like a maître d’—the door already shut, the lock already set. “We’re leaving,” he said. “We’ll be next door when the explosion takes what little is left of you.” He put a hand on my mother’s elbow, and she followed a step behind like a planet in a bad orbit. “Mom,” I said. It came out on a breath already heavy with gas. She looked back, the smile briefly cracking to show a seam of fear, then snapped shut on command. They left. The bolt stuttered into place.

I turned to Sarah. Her face, ordinarily bright with a kind of battle cheer, had gone pale. She lifted her phone and tapped. The bars at the top sulked at zero. “Text anyway,” I said. “Sometimes the god of weak signals likes a challenge.” I typed the address and the words gas leak basement locked with fingers that already felt dumb. I sent it to my CO, to a number at the Fort Campbell desk, to 911, to a neighbor whose last name I didn’t remember, to three people who owed me favors and one who didn’t. The messages blinked out with the lazy air of travelers who weren’t sure they’d get where they were going.

The window a foot below the ceiling had been painted shut since I was eight. I told myself this like it was useful information, then grabbed a wrench off my father’s workbench and flung my phone at the glass with a violence that surprised me. A hairline crack reached across the pane like an idea getting brave. Sarah followed with a hammer. We took turns until we weren’t taking turns anymore but swinging in a rhythm that felt like prayer. Paint flaked into our hair. The glass buckled. Then the pane broke with a little cry of freedom and we were breathing winter air in a Michigan fall, which is to say air with a memory of cold.

The gas still poured. The air refreshed at the window. The math stayed bad.

“Door,” Sarah coughed. We both stared up at old oak, thick as a judge. The hinges were on the other side. The lock sat back there too, smug and invisible. We shoved a bookcase across the floor and leaned it against the door from below, braced ourselves, and pushed. The frame held. Our shoulders lit up like protests.

I laughed, the hysterical kind that comes when your body’s telling you jokes so you don’t notice you’re drowning. “We need a fairy tale,” I told her. “A helpful animal. A sudden axe.” Sarah’s eyes had narrowed to slits, a soldier’s version of prayer. “We need time,” she said, and the word swallowed itself.

I climbed onto the workbench and hauled myself up to the window, ignoring the bite of leftover glass. Outside, night had the blue of an old bruise. The backyard where I’d once learned cartwheels looked smaller, like someone had washed it in hot water and it had shrunk. In the neighbor’s yard, my mother’s silhouette stood against the house like a stain. Beside her, Frank scratched at his beard and checked a watch that probably told him what time it was for people who thought they had time.

Then, a color I had prayed for since the lock: red and blue hopped the corner. I let myself feel one inch of relief, then bit it back. Sirens in the distance are not sirens at the door. Sarah’s hand reached up and I grabbed it, hauling her toward the breath of outdoors. She scraped an elbow, swore softly, and laughed into the fresh air the way you laugh at a punchline that lands after a long setup.

Firefighters eat danger for breakfast. They hauled the door like an insult and popped it from the hinges with a tool shaped like the end of an argument. The sound the lock made as it gave up—cheap metal failing its own promise—will be with me until my last hour. The first wave of clean air hit me hard enough to make me dizzy. Hands guided us upstairs like the hands of people who move other people for a living.

Outside, the world resumed its usual sizes. I collapsed onto the grass that had grown wild around the pickets. My lungs felt like paper bags. An EMT put oxygen on me with a neat efficiency that made me want to weep. Across the gap of yards, police officers asked Frank questions. He performed for them like a man who’d rehearsed. “They broke in,” he said. “They attacked us.” My mother stood beside him in a long-sleeve shirt in September, arms already patterned with fresh, theatrical bruises. Her mouth was a line stretched too thin to hold.

I had my phone. I had the email. I had the metadata. A cop with forearms that knew their work glanced through my cracked screen while a firefighter jogged a wrench along the gas line and turned the hiss into blessed quiet. The cop asked me if he could take the handset for a second, and I let him, because sometimes you win by giving up a thing you love to someone who’s stronger than you are.

Frank’s eyes found me across the distance, and what I saw there was not fury but a kind of cosmic disappointment, like a man robbed of an ending he wanted to tell for the rest of his life. The smile that replaced it was smaller than he was used to, and therefore truer. The cuffs went on like punctuation. My mother’s breath finally hitched and entered the world as sound. You would’ve recognized the noise if you’ve ever heard a dam fail.

In the ambulance, two oxygen masks made a small cottage of plastic around Sarah and me. I felt my chest loosen with each hiss, like someone was greasing a hinge. Sarah’s knuckles brushed mine on the gurney—an accidental touch turned ritual. She tilted her head toward the open doors and the wide night. “Still think you can save her?” she asked. I watched my mother fold down in the back of a patrol car, the line of her shoulders a signature I had known all my life. “No,” I said. “Saving is not the verb anymore.”

The prosecution loved the story of a woman soldier returning home to a trap. They were less keen on the story of a mother who smiled while the gas rose. Juries are built to cradle mothers gently. We had the email, the timing, the unambiguous lock, the firefighters’ statements, the photos Mrs. Henderson had sent before, the audio of Frank in my apartment threatening like a man who thinks threats are a spice you add to a meal. Evidence stacks itself willingly if you lay out a neat table.

In the days before the hearings, I discovered a strange new kind of tired—the tired of someone who has been right too long. I sleepwalked through debriefs. I told the Army the truth in a voice that wasn’t mine, a register borrowed from a woman who had practiced in a mirror. The JAG officer assigned to me was young, careful, and fond of the phrase “let me be clear.” He drew a map of the possible outcomes with a pen that tapped. “Frank will try to turn this into a thing about you,” he said. “Military. PTSD. Temper. He will imagine a version of you he can beat in a story. We will bring facts.”

The preliminary hearing was theater in miniature. Frank wore a suit that fit like a grudge. His lawyer referred to him as “Mr. Dalton,” as if respect could be conjured by syllables. My mother sat behind him in a blouse with a soft little bow at the neck like someone had told her that softness could perform miracles. When she spoke, her voice was steady, and each word felt machined. “He never touched me,” she said, as if reading from a hymnbook. “Emily has always had a problem with Frank.” The judge listened like a man listening for the small feet of truth and hearing only rats.

But truth is patient. It watches your mouth lie and then walks in wearing evidence.

The felony charges took. The conspiracy language landed like a hammer. “Attempted murder” is a phrase that changes the weather in a courtroom. The judge’s face took on the set of a man who has read enough stories to know the ending before you do. Frank wasn’t good at being small in a room. Under the prosecutor’s bright lights, he got tall and dangerous and careless. When asked if he considered himself the head of the household, he said “somebody has to be.” When asked whether anyone had ever been afraid of him, he laughed. That sound wrote footnotes in all the right places.

My mother’s deal materialized when her story snapped. The email, the fake bruises, the gas turned up by a hand that wasn’t mine. She turned and saw the ledge and the drop beyond, and something in her face changed like a light that had finally decided what color it wanted to be. She agreed to cooperate in exchange for a smaller sentence. I did not cheer. Sometimes justice is a person standing still while someone else opens a door and says, “Go on.”

In the hallway after the hearing, I leaned against a tile wall and felt the weight of everything I’d carried since Route 23 had changed the shape of my life. Sarah slid down beside me like a coin in a slot. “How are you?” she asked, the question people ask because they want an answer and not because they expect one. “Like I’m at the edge of the map,” I said. She put her head back and stared up at the fluorescents. “Then we draw more map,” she said, “or we fold the corner and say here there be dragons.”

I laughed, not because it was funny, but because it was a way to put two hands on the problem and lift. We drove back to the hotel that night, the highway quiet in the way highways get when they’ve absorbed too much noise during daylight. I dreamed of flooded rooms and doors that open like mercy. I woke with the desert taste of oxygen on my tongue, turned toward the window, and watched day begin. It is the one trick day knows: it begins.

The trial waited. The story had an ending somewhere ahead. It didn’t have the ending I wanted when I was twelve—nothing in the world does—but it had an ending that would let me breathe. Sometimes, survivors must settle for air.

Part IV

The courthouse in our county was a three-story barge of brick that looked like it had been moored there since the river ran backward. I showed up in dress blues the morning of my testimony, the cloth holding its shape the way I held mine. On the chest, the Purple Heart glinted like something earned in a different book, but I set it there anyway. Not for theater. For truth: I had been in rooms where noise went far past anything a bat in a basement intended.

The gallery filled with neighbors hungry for spectacle, with soldiers from Fort Campbell who understood chain of command better than family, with local reporters fanning themselves with legal pads and hopes of a lead. I was sworn in and sat in a witness chair that knew more about human weakness than any priest’s confessional. The prosecutor—a woman with the temper of a schoolteacher and the patience of a tollbooth—asked me to tell the story. I told it straight. When I got to the part about the smile on my mother’s face in the basement—the smile like a misprinted prayer—the room made a little noise, a stifled gasp that dressed itself quickly in silence.

Frank’s attorney went at me like a man looking for a path through a crowd with his elbows. “Isn’t it true you’ve harbored resentment since adolescence?” he asked, smoothing his tie, trying to put me there again—fourteen, small, seething. I told him the truth he wasn’t expecting: “Yes. I resented a man who installed himself over my father’s ghost and treated us like furniture, who isolated my mother and tried to keep me from school and work and air. I resented that. I grew up.” It’s hard to cross-examine a person who walks you to your own question.

He tried the veteran angle. “PTSD?” he asked it like a charm he could mutter to turn gold into straw. I said, “I have a therapist and a duty station, a rank and a record, and a wound that was stitched at a base hospital with Frank’s fingerprints on the form. If you want to make me a caricature, you’re going to have to draw better.” The judge hid a smile in his sleeve.

Then my mother took the stand and the room rearranged itself around her like rooms do around women who’ve been told to be the center since how to bake was considered a political act. The deal had changed her posture. She looked ten years older but stood straighter, as if a body can inherit dignity from a confession. She took a breath and let the line of her life spool out in front of strangers—grief in October, the slide into fog, the man who built himself into our kitchen, the way she had learned to measure out her days in apologies. She said the thing I needed her to say and the thing I didn’t want to hear: that she had, at times, wished the target were my back instead of hers. I heard a few chairs creak behind me as human beings flinched in unison.

I watched her mouth shape the word sorry and watched how the jury weighed it. “I became a monster,” she said—five words that fit in your palm, heavy as lead. The prosecutor let the sentence hang like laundry on a line, the breeze doing the work.

Frank took the stand because men like Frank think the last word belongs to them the way they think rooms do. He attempted to be reasonable the way a man attempts a language he didn’t take time to learn. It lasted five minutes. The prosecutor asked about control and he sang a small hymn to it. She asked about fear and he called fear “womanly.” He used the phrase “firm hand” without irony and then wondered why the air cooled. He referred to my mother as “my wife” so many times it stopped sounding like human speech and started sounding like a misplaced deed.

When the verdict came, it was quick—not because the jurors didn’t care, but because caring made them efficient. Guilty stepped into the room like a person. The numbers attached to it—twenty years without parole—flashed in the fluorescent light and then settled around Frank like a suit looped over a chair. He raged as if rage could push time over. The bailiffs shepherded him out like men moving a bull. I watched him go because witnesses owe themselves that.

My mother stood to hear her own sentence. Five years, likely two, maybe less, for cooperation that had turned the lock from the inside. She looked at me as the deputy touched her elbow, and in her eyes I saw a room with a single chair and no windows. “I know you won’t forgive me,” she said when she passed near enough to make the air vibrate between us. “I wouldn’t forgive me either.” The deputy took her away and the door swallowed them both.

Outside, the air was rude with sunlight. The reporters asked questions like crows—loud, eager, unembarrassed. Sarah glided between them as if parting reeds, putting a hand on my shoulder not to steer me, but to make sure I remembered there was a body attached to the name they were saying. She led me down the steps and into a pocket of shade. When she produced a bottle and two paper cups from her tote like a magician doing a small trick after a funeral, I loved her more purely than I had loved anyone who wasn’t my father. “To survival,” she said, and the whiskey told me the truth about my throat.

“How do you feel?” she asked, which was our way of setting stakes into ground that moved. “Like I can breathe,” I said, and meant it. “Like I can walk into a room and it’s not a trap.” We sat and watched Riverside drift by: minivans with soccer stickers, the mailman limping slightly, a girl on a bike who didn’t know she was crossing a battlefield.

That night, lying in a borrowed bed at a friend’s house, I tried to think of the right word for what had been done. Not justice exactly. Justice implies a balance we rarely achieve. Not closure. Only neat stories close. Maybe simply end. The thing had an end. It would not surprise me at the grocery store anymore. It would not sit heavy on my chest at midnight and tell me to be smaller. It would not change the colors of rooms.

I dreamed of the kitchen table in our house with the good light. I dreamed Dad sitting across from me, pencil in his hair, tapping out a rhythm with the eraser that meant “you know this,” and me looking down at a fraction that wanted to ruin me and hearing his voice: Everything is just the next little step. In the morning, eyes open, I said it out loud into the quiet: the next little step.

The next little step was home. Not the one on Maple Street that had lost the right to that word. The home I’d built with habits and paychecks and rank. The home with four a.m. wakeups and jokes you only understand if you’ve crawled under a thing and pushed. The home with Sarah’s boots in the hall and a coffee mug that said World’s Okayest Soldier because she knew I hated striving and loved honesty. The Army can’t be everything, but for a while it was enough.

The Army had one last conversation for me, though. My CO called me in and stood like a person who’s rehearsed for a delicate talk, then decided to go off book. “Carter,” he said, “when you’re ready, take a long weekend. Take two. I’m filing the paperwork so you don’t have to. Go somewhere quiet that doesn’t smell like paperwork or court.” He cleared his throat. “You did good.” I nodded, which is sometimes all the ceremony a compliment needs.

We packed up Sarah’s car the next Saturday and pointed it south. The radio found stations that hadn’t been invented the last time I’d driven those roads. In a diner with cracked red booths halfway to Tennessee, I ate eggs and thought about how grief and rage had once taught me to starve. We got sticky buns for the road because we were alive.

On the base, I hung the uniform in the closet like stowing a flag after a parade. I took a shower so hot it felt like cell walls opening, and when I stepped out, I found Sarah on the couch pointing to her phone. “Henderson,” she said, and tapped play. My neighbor’s voice came small and close. She’d called to say the house on Maple had been sold—an investor, a man with plans for rentals. To say that there would be new paint soon, a new fence maybe, renters with different troubles. The world keeps moving its furniture.

I stood in the doorway between the kitchen and the living room while the water dried on my shoulders and decided—with as much ceremony as a soldier turning to face a flag—that I would not go back to a zip code that had built a trap around my name. Not for at least a long time. Not until the word “mother” stopped being a blade and started sounding like hope again. I could do that for myself, and not because I was hard. Because I had learned how to be soft without being broken.

Sarah patted the cushion next to her. I sat. She handed me a bowl of something green and virtuous. I took it and balanced it on my knee. “So,” she said, mouth tilting, “about Germany.” I laughed. “About a house,” I said, “with a yard and a fence that means nothing except ‘the dog can’t get out.’ About a kitchen where cinnamon means cookies and not trying to cover a smell.” She nodded. “About a family we choose.” We said it together and we said it like an oath.

The phone buzzed on the table later, a low insect sound. It was a number from a county office, some square of the state still tasked with handling my mother. A woman with a pleasant phone voice told me the basics: placement, visitation rules if I wanted them, the mechanics of incarceration in a place that still called itself a correctional facility even when it only managed containment. “Is there anything you’d like us to pass along?” she asked like this was a natural and reasonable thing.

I swallowed. I did not trust my voice. “Tell her…” I began, then stopped. The sentence I wanted to say—tell her I love her—felt like sugar poured into a machine that hadn’t earned sweetness. The sentence I did say felt like lifting something both heavy and light. “Tell her I’m okay,” I said. “Tell her I’m strong.” It was kinder than she deserved and exactly what I needed to say.

I went to my desk and pulled out a sheet of paper. My handwriting had grown sharper in the Army. I wrote: Mom, I hope you use the time to find the person you were before grief turned you cruel and fear turned you loyal to the wrong things. I won’t visit for a while. That’s not punishment. That’s healing. You taught me to bake cookies and sing off-key. Frank taught me to fight. I’m choosing the first lessons now. —Emily

I did not put it in the mail that night. It sat on the desk like a small animal waiting to be fed. I would mail it when my hand didn’t shake. The next little step.

Outside, the base quieted into a night that sounded like safety. The war I had been fighting since I was twelve was over. Not because a judge said a number. Not because a gavel knocked wood. Because I said so. Because I could set down a weight and not pick it back up as a habit.

My name is Emily Carter. I have been prey and I have been a soldier, and now I am a person who wakes to alarms and coffee and chosen family. There is nothing ordinary about that. There is everything.

Part V

Time leaves fingerprints even when you’re not looking. Seasons ran their loop around Fort Campbell while I learned the new choreography of a life with less fear. I found myself trusting ordinary things again—a lock that clicked, a shower that steamed, a pair of keys always where I set them. I bought a couch with my own money and fell asleep on it with a book across my chest like a cliché I’d earned. On Saturdays, Sarah and I ran the greenways and called cadence just to hear our voices bounce off trees. Sometimes at mile three I felt my chest go light in a way that had nothing to do with breath.

Work was work. Intelligence doesn’t care about your past; it cares about patterns. I sat in rooms where maps throbbed with red dots, where we named storms overseas and tried to steer people around them. The language of risk analysis dovetailed too neatly with my own history, and sometimes I needed to step out into a corridor and put my head against the cool paint until the world steadied. Then I went back in and did my job because I am good at my job. Survival is a skill set. The Army pays for those.

On a Wednesday with rain on the forecast and an exercise on the calendar, I received a letter forwarded through the official system from a prison two counties north of Riverside. The envelope was institutional—yellowed and thin, the kind of thing that looks apologetic before you open it. I took it to the small square of grass behind my building and sat on a step that let my feet find dirt. I read my mother’s handwriting, which had learned neatness from a teacher’s grade book and cruelty from a bad marriage.

Em, it began. The nickname made the edges of my vision go fuzzy. I don’t expect you to read this, but I hope you do. There is a class here on rebuilding your life, and I have learned how to tell the truth. I am sorry in a way that does not ask you to lift any part of my apology. I was weak when strength was required, and then I was worse: I was willing. I will not ask you to forgive me. I will ask you to spend your days on joy and the family you’ve chosen and work that feeds you. When I picture you, I try to picture you twelve, at the kitchen table, with your father’s pencil in your hair. It is the only picture I can stand that doesn’t drown me. I love you. That is not a request. It is a fact. —Mom

I held the letter in hands that had stitched and choked and saluted. The wind caught a corner and tried to take it away, but I put a palm flat and kept it. I didn’t write back right then. I didn’t throw it away either. Not everything requires an immediate answer. Not everything grants one.

The house on Maple became a rental and then a starter home for a couple no one on the block knew. Mrs. Henderson sent a photo at Christmas: the new owners hung lights and a wreath. The fence looked freshly painted. If I let my eyes go soft, I could see my kid-self in the upstairs window practicing scales she would never be good at on a piano that smelled like lemon oil. I closed the message and went to the range and put holes in paper and pretended I was making lace.

On a Sunday morning in spring, Sarah and I drove to the dog shelter and adopted a mutt with the grin of an unrepentant thief. We named him Mustang because we are sentimental and because names can rewrite the past if you whisper them enough. He chewed two shoes and an NCO Academy study guide and then settled into being loved like it was a job he was born for. He herded us from room to room, keeping his flock in order, and learned the route of our runs so precisely he’d pull us left three seconds before we needed to turn. Chaos redeemed is comedy. We laughed a lot.

A year after the trial, the Army sent me downrange. Afghanistan held heat like a grudge. The work was the work, and I won’t dress it up for you. Some days I sat in a room with air that tasted recycled and told people where they could walk and where they couldn’t. Some days the phone rang and the voice at the other end had a tone that meant the worst thing had just happened to someone with a name. I did my job. I watched helicopters draw lines across the sky like children’s scribbles, and sometimes when the wind shifted, I smelled dust so fine it became a taste. In the evenings, we sat on a low gabion and passed a bottle that probably wasn’t there and told jokes that definitely were. I came home with the same number of pieces I left with. That’s a kind of luck that can bruise you to consider.

Back at Campbell, they pinned on a new rank with a ceremony that lasted precisely as long as it needed to. The sergeant major said a few words about leadership that made me look at the floor because sometimes praise sits heavy as punishment, and then we ate cake so sweet it hurt. I licked frosting off my thumb and looked around at a room full of people who would walk into burning buildings if I asked and knew I would never ask that lightly. The Army has many flaws, but it is good at giving you a tribe.

Near the end of my enlistment, an offer came that would have made earlier versions of me weep: a slot at the warrant officer course with a follow-on to a unit that did work I can’t write here, and wouldn’t if I could. Another offer came in quiet tones from the civilian world: an analyst position with a private firm that paid in ways the Army doesn’t even pretend to. And then there was the thing Sarah suggested while we ate pho in a strip mall with a linoleum floor: “What about school,” she said, as if the word meant sanctuary and not debt. “What about you at a desk in a classroom where no one barks, where your intelligence gets to feed instead of fight?”

I went home and pulled out a box I hadn’t opened since basic, the one with the brochure a guidance counselor had slid across a desk. I had become the girl on that cover. The question was, did I want to be her forever. I slept on it. Mustang snored like a tiny engine. In the morning, I said the thing that surprised me most. “I want to sit at a kitchen table again,” I told the room. “I want to study something that isn’t war.”

I ended up taking the private firm’s offer with a compromise plan that felt like a bridge: classes at night, tuition paid because the Army had decided to be generous for once and because I had bled for that generosity, and a job that let me learn a new vocabulary of threat that didn’t always involve the sound of rotors. I moved off post into a small bungalow with a yard exactly the size of a Sunday afternoon. I painted the walls a color that can only be described as hope watered down with practical sense. I bought a second mug and left it in the cabinet for guests I hadn’t met yet.

On the anniversary of the trial—and it’s a choice to count that kind of time—I wrote my mother a letter that did not tremble. “I’m okay,” I told her again because repetition is a kind of healing. “I have a dog who thinks he owns the sun. I have a friend who is my sister. I have a job that respects me, and I respect it back. I don’t forgive you yet. I don’t know if I ever will. But I am spending my days on joy, like you told me to. It’s working.”

She wrote back in small, careful sentences. She told me about books she was reading with other women who had learned how to breathe like a task. She told me about a class where they made bread and the feel of dough waking under her hands. She wrote about singing badly in a chapel with other voices, and how nothing we do can ever make music less holy. She did not ask for anything. She said thank you for the letter. She said I love you once, like placing a coin in a dish you don’t expect to get back.

When she came up for parole, I did not go. I sent a letter that said I would not object. I signed a document. I kept my promise to myself and did not bend the world out of shape. She was released to a room above a church that had seen worse. Mrs. Henderson texted me a photo because of course she did—my mother on a bench under a maple that hadn’t dropped its leaves yet, looking at nothing in a way that suggested she might choose to look at something soon. I put my phone face down on the table and pressed my palm to the wood that had been mine long enough to know me. I asked the air if it thought I should call. The air said nothing.

On a Tuesday that had finally given back what the first Tuesday had taken, I sat at my own kitchen table—books open, pencil tucked behind my ear like a spell I could cast. The afternoon light slid across the surface the same way it had in the house of my childhood, a slash of mercy. I was working derivatives for a class that would lead to statistics that would lead to a degree that would lead to, who knows, maybe a chair at a table where other women sat, high windows, good coffee. Mustang lay belly-up in a sun square. Somewhere in the living room, Sarah laughed at a show that always ended with someone learning to tell the truth.

I heard it then—the sound of my father’s voice, not as a ghost, but as a habit I had kept. Everything is just the next little step. I had taken a thousand small steps since the night the gas hissed in the basement and my mother’s smile froze. Some were ugly. Some were beautiful. None of them were simple. All of them were mine.

At the end of the day, when the light faded and the cool came on, I stood in my yard and looked up. The sky above Kentucky has the same unbothered blue as the sky above Michigan on a good day. I thought about forgiveness like a road I didn’t have to drive today. I thought about the girl I was, the soldier I became, the woman I am, and how all three deserve a seat at this table. I said their names, softly: Emily at twelve. Emily at twenty. Emily at twenty-eight. They all looked up inside me. They all nodded.

The ending of this story is not a clap of thunder or a door slamming shut. It is a field at dusk, a dog putting his head in your hand because he knows you’re thinking too hard, a friend calling from the doorway to ask if you want tea, and you saying yes because yes is a word that makes rooms brighter. It is a letter in a drawer that you might answer someday. It is the kind of quiet that tastes like clean water.

When people ask now—because they do, because I told the story and asked them to tell me theirs—if I forgave my mother, I tell them the truth: forgiveness is not a trick I owe anyone and not a field I have to cross to get to the rest of my life. Some days I stand at the fence and look at it. Some days I turn around and go back into my bright kitchen and stir cinnamon into batter and sing off-key and laugh, because the child who believed laughter could raise the dead was right about some things.

My name is Emily Carter. The basement is behind me. The door is open. The air is sweet and ordinary. The war is over. I won—not with violence, though I used it when I had to, not with rage, though I let it lift me when I needed a tide. I won by walking out of rooms that wanted to make me small, by building new rooms with better light, by choosing a family that would rather hand me a rag to help with the mess than a story about why the mess is my fault.

If this found you somewhere hard, consider this a hand on your back and a voice in your ear: the next little step. That’s all. That’s everything.

Part VI:

There’s a kind of quiet that happens in late summer where crickets stitch the dark together and you can hear your own thoughts walking around. On one of those nights, a year and change after the verdict, I sat at my kitchen table with the window open and Mustang snoring at my feet and a breeze stroking the curtains like a hand that knows you. The table was covered with homework—my homework—stats problems blooming like constellations across a legal pad, a textbook bulldozed open to a page with too many Greek letters, a coffee mug I’d forgotten to rinse. Sarah was out of town for a comms exercise; the bungalow had that hollow echo of a voice you miss because it’s not there to answer back. I’d spent an hour pretending to study and ten minutes actually doing it, the way you do when the mind wants anywhere but the page.

The letter from my mother lay by the salt shaker, opened and re-sealed so many times the envelope had the fatigue lines of a face. I’d stopped keeping it in a drawer; I didn’t need to hide my history from myself anymore. This one was shorter than the last: I’m working in the church kitchen. We make soup on Thursdays for anyone who needs it. I peel a lot of carrots. I think of you when I cut an onion and don’t cry. I sing when no one is in the sanctuary. Off-key. I remember it made you laugh. If you ever want to meet somewhere public, I’m ready to listen. —Mom.

Public. Ready to listen. It read like someone who had been tutored in the language of boundaries and was trying to pass the test. I traced the indentations of the writing with my thumb and sat with the weight of a question I had been carrying since I was twelve without having the words for it: what do you owe the people who made you and broke you in the same breath?

I stood up, because some questions can only be answered on your feet. I leashed Mustang and walked the warm streets until the base lights winked in the distance and the smell of cut grass gave way to the smell of hot pavement. Big decisions sometimes like company; the rhythm of a dog pulling gently toward whatever interesting thing the nose finds is decent company. I practiced my answer to no one. I can meet you. I can listen. I can leave if I need to. I am not a girl. I am not prey. I am a woman who can walk out of any room. The words sounded like a cadence call in my head; the step felt steady.

I chose a diner two towns over where the waitress called everyone “hon” and the coffee refills were automatic. I wrote the time and place on a simple postcard—no florals, no sentiment—and dropped it in the mail before my body could change its mind. The card was new. The decision had taken years.

On the day, I wore civvies that made me feel like a person who chooses her own weather: jeans soft from use, a white shirt with sleeves I could roll, boots that didn’t announce themselves. I left my uniform and my medals and my training at home—not because I was ashamed of them, but because I wanted this meeting to be about the person under the armor. Sarah offered to come and sit at the counter like backup; I said no and meant it. The point wasn’t to prove I didn’t need protection. The point was to decide what I needed in real time and honor that decision.

Mom was already there when I walked in, in a corner booth by the window. She’d cut her hair short; it framed her face in a way that made the bones look honest. She wore a simple blue blouse and no bow. The waitress had set water and coffee between them like a peace offering. My mother’s hands lay palms-down on the table, fingers unclenched. She didn’t touch me when I slid into the seat across from her; I didn’t offer my hand. We just looked, two people inventorying the damage and the repair.

“Hi,” she said, and it was the voice from my childhood, the one before grief got its teeth into the throat of our house. “Hi,” I said back. The word felt like a small boat pushed off into water.

We ordered pancakes because pancakes are what you order when you’re trying to remember how to be a family. For a minute, we did small talk badly—the weather, the church kitchen, the way Mustang had recently learned to open the trash and throw his own party. Then the waitress gave us a blessed island of silence and I took it.

“If we do this,” I said, and my voice didn’t shake, “we do it by rules I set. No minimization. No excuses. No retelling the same story until it becomes prettier. If I ask for a pause, we pause. If I need to go, I go.” I expected argument or at least an offer to bargain. She nodded. She didn’t reach for anything—not the sugar, not my hand, not a justification. She said the words that are a skeleton key in most rooms: “I hear you.”

We started in the before, because that was the only place we could both breathe. She asked about Dad. I told her the way he tapped a pencil when he thought. She told me about the first time she saw him, at a hardware store, blushing over screwdriver sizes like romance had a shy cousin. We built a small shelter out of those stories. It wasn’t enough to live in. It was enough to stand under while the next part came.

“I hate the basement,” I said finally, the words a weight put down on the table between us. “Not just for the gas. For the smile.” She closed her eyes. When she opened them, there was no fog there, only the kind of clear that comes after rain. “I know,” she said. The waitress set pancakes down and we ignored them. “I smiled,” she said, and I watched her make herself say it. “Because he told me I looked ugly when I cried. Because I thought if I could be what he wanted, I could control the explosion. Because cruelty had replaced sense. Because I was angry at you for leaving me alone with him, which was not really anger at you at all, but at myself for not leaving with you. Because I had become someone who mistook compliance for survival. Because I was wrong.”

There are apologies that try to tap-dance the listener into forgiving. This wasn’t that. This was standing in the middle of the stage without music. I let the silence have a minute. I cut into a pancake and watched butter shine. “I don’t know if I can forgive you,” I said. “Not because I like holding a grudge. Because I would have to build a bridge to reach you, and bridges that long take time I might want to spend elsewhere.” She nodded. “I’m not asking,” she said. “I know the cost of bridges. I’m just… here. On my side of the river.”

We ate some and talked more. She asked about the Army like someone asking about a foreign country she might visit in her next life: what’s the food like, the holidays, the words they use for love. I told her about Sarah without giving too much away; I told her about Mustang because dogs allow you to be soft without bargaining with your pride. I talked about the degree program and the way my professor wore bow ties and threw chalk like confetti when someone got a proof right. She laughed, a small trial version of the old laugh. It came out of her and seemed to surprise her before it pleased her. I let it be. We didn’t need to push good things. We could let them arrive on their own feet.

Finally, when the coffee was cooling and the pancakes looked like maps someone had torn, she reached into her purse and pulled out a small, carefully wrapped bundle. She slid it to me without commentary. I peeled back the paper and found Dad’s pencil—the same yellow, the eraser worn to a nub, the metal ferrule dented in places he’d worried it while thinking. I had not known it was still in the world. My breath hitched and made a new sound. “I kept it,” she said, answering the question I couldn’t shape. “Even when I let everything else go. I thought you should have it. I thought maybe you already did, inside your head, and this could be the proof.”

I put the pencil down next to my plate like an heirloom in a museum. The urge to steal it back into my pocket and run was so strong it almost felt funny. “Thank you,” I said, and the words did the work of grace without promising anything else.

We paid. We stepped outside. The afternoon had turned stormy; somewhere, thunder cleared its throat. We stood on the sidewalk like people at the end of a good movie who don’t want to move first and ruin the spell. “I can do this again,” I said, meaning meet, talk, eat breakfast in mid-afternoon. “Not soon,” I added. “But again.” She took a breath like somebody handing herself a gift. “Again,” she said, and did not try to make it more than it was.

We hugged awkwardly, the way you do when boundaries and longing crash into each other in public. It wasn’t a reconciliation; it was a cautious handshake between past and present. It was enough for now.

In the weeks after, life kept being life. Sarah came home and tossed her ruck on the floor and told me a long story about a comms blackout that ended in triumph and pizza. Mustang learned to drop the trash lid on his paw and yelped, then milked the injury for all the couch privileges it was worth. I passed a midterm that had been beating me to death with Bayesian theorems and walked out of class feeling taller than I am.

Work took me to D.C. for a two-week project, and in the evenings, I walked the Mall and let monuments lecture me about courage and contradictions. I stood in front of a wall of names and thought about the ecological truth of surviving—how it’s not a merit badge but a bruise you learn to wear until it stops hurting and becomes a story you tell when you need to remind yourself of your size.

On a Saturday between assignments, Sarah and I pointed the car north and kept driving until the Mackinac Bridge rose up, a rib cage laid over water. We stopped on the island where my father used to take us and rented bicycles with gears that didn’t believe in us. We pedaled past fudge shops and horses with tails like metronomes, and found a patch of shoreline where the rocks are honest and the lake gives you permission to be quiet. I took the pencil out of my pocket and set it on a flat stone, not to leave it, but to let it see the water. I told Dad out loud the thing I didn’t know how to fit into a prayer. “I made it,” I said. “It wasn’t pretty. But I made it.” Sarah squeezed my hand and pretended she didn’t hear, which is to say she heard it exactly right.

When we got home, a card waited in the mailbox from my mother, one of those blank ones you buy at the drugstore because the picture looks like it might carry some of the meaning for you. It was a photograph of a field at dusk, the sky the pink-blue of the inside of a shell. Inside, she wrote: I’m planting tomatoes next spring in a community plot behind the church. Too many, probably. Some habits are harder to break than others. If you want any, I’ll bring them to the diner. If you don’t, I’ll give them to somebody else. Either way, I’ll plant them thinking of you.

I set the card on the fridge under a magnet shaped like Kentucky and left it there like a promise to decide later. Not everything demands an immediate yes or no. Some things want you to stand in front of the answer for a while and just breathe.

The fall slid toward winter the way a hand slides into a coat pocket. I took a job interview I hadn’t planned on taking and got an offer I wasn’t sure I wanted and said yes because I had learned how to say yes like a tool and not like surrender. The firm would have me work a project in Detroit for six months—data, risk models, boring to anyone who hasn’t had their life rearranged by numbers and red flags. The map said I’d be within a few hours of Riverside. The past raised an eyebrow; the present said we’re good.

On my first weekend in Michigan, I didn’t drive south. I drove west to the lake and sat in a coffee shop that didn’t exist when I was a kid, watching college students argue over nonsense that felt beautiful because it wasn’t life or death. I wrote a paper. I watched snow begin in the air and end as water on the sidewalk. I let the state be itself without climbing inside the old house in my head.

The next weekend, I texted my mother: soup on Thursday? She sent back a spoon emoji and a time and, somehow, a sense of relief that fit into those characters. I went to the church and stood behind a line of men and women who knew more about hunger than I would ever learn in a classroom. My mother ladled soup and handed out bread. When I got to the front, she didn’t say “this is my daughter” to the woman beside her. She said, simply, “this is Emily,” and put an extra scoop in my bowl. We ate at a plastic table with a nick in it shaped like Michigan and then we washed pots in a kitchen that smelled like onions and mercy.

It wasn’t forgiveness. It was living.

Two months later, I sat in a courtroom again, this time not as witness or victim but as a citizen bored out of her skull on jury duty, reading a paperback between voir dire questions and looking up when a judge cleared his throat to keep the room disciplined. I watched the theater of it all and felt the old electricity in my skin, then felt it leave like weather moving east. On a break, I stood at a window and looked out over a city that had taught itself new tricks to survive. The skyline had scars and new growth. It reminded me of me.

When my stint in Detroit ended, I drove south with the trunk packed in a way that said small life, big enough. I stopped at the diner on the way and left a brown paper bag with tomatoes at the counter because I had accepted her offer and now it was my turn to give back without ceremony. I wrote for anyone on the bag and smiled when the waitress said, “these look good, hon.” I didn’t leave a note. Not every kindness needs a signature.

Back at the bungalow, the grass had done its unruly best. Mustang ran the fence line as if greeting each blade by name. Sarah sat on the porch steps with two beers and a look that said welcome home without making it a speech. We sat until the sky remembered how to be stars. We talked about nothing important. We talked about everything.

That night, I put Dad’s pencil on the kitchen table and tucked it behind my ear while I worked another problem set. I thought about a basement that would never have power over me again, and about a woman who was learning how to make soup and plant tomatoes and sing off-key in a place with stained glass. I thought about a man in a prison who had lost the power to define the temperature in any room I entered. I thought about a girl who had promised never again and a soldier who had kept that promise and a woman who had learned that sometimes the bravest thing is to lay your weapons down and pick up a whisk.

The ending of my story is ordinary on purpose. It is the sound of a dog dropping his ball at my feet. It is the ping of a text from Sarah that says you up? and a reply that says always. It is a kitchen that smells like cinnamon because there are cookies in the oven and not because anyone is trying to cover anything. It is a field at dusk, the sky the pink-blue of the inside of a shell, and me standing with my hands in my pockets, letting the air do what air does best.

If you need a moral, make it this: survival is not a single victory. It is a practice. It is the way you turn toward the next little step even when the last one hurt. It is the way you learn to forgive yourself for the seconds you were small and the minutes you were cruel and the hours you were afraid. It is the way you decide that love will mean boundaries and not bargains, and that family is a verb you can conjugate with people who earned it.

I keep the pencil on the table. I roll it between my fingers when a problem won’t yield and hear Dad’s laugh under the hum of the fridge. I write my name—Emily Carter—at the top of a page, and the letters look steady. When the night gets too quiet, I open the window and let the crickets stitch me back together. I don’t wait for thunder. I am not worried about storms.

The war is over. I don’t need a flag. I need a kitchen, a friend, a dog, a job that uses my brain, and a sky that remembers me. I need a mother who plants tomatoes and doesn’t ask for more than I can give. I need a field I can cross when I’m ready, and the knowledge that I can stop halfway and sit in the grass and still call it progress.

My stepfather beat me in the basement once, and my mother smiled while I fought to stay conscious. Once. That’s important. The rest of my life is the opposite of that moment. Sometimes, even now, when the house is still and the pencil is warm from my ear, I say it out loud so the air can hold it with me: Once. Not always.

Then I turn the page and take the next little step.

THE END

News

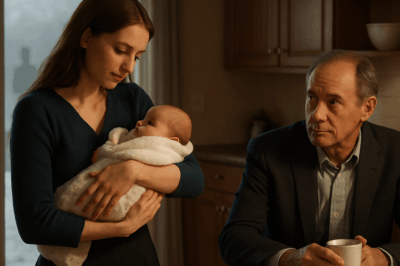

That Summer Day, Routine Shattered: Nancy Walked Into the Kitchen, Eyes Downcast, Cradling a Dark-Skinned Baby—Unaware of the Storm About to Break CH2

That summer day, the routine shattered. Emily walked into the kitchen, eyes downcast, a baby cradled in her arms. A…

Shut up while I give you money,’ my husband smirked, not knowing that in the morning security wouldn’t let him into his office: I would be the one signing the termination order. CH2

“I told you, I’ll handle this myself,” my husband snapped, tossing his coat onto the chair. The smell of expensive…

— Do whatever you want, but by tonight the things your sister stole from me had better be back home! If not… then don’t bother coming home anymore! Go live with your sister! CH2

“Your sister stole from me.” For a few seconds the line filled with a dense, heavy silence in which only…

HOA Karen Poisoned My Lake to Prevent Me From Fishing — Didn’t Know Their Water Supply Depends on It… CH2

I never thought I’d end up in a fight with my homeowners’ association over something as simple as fishing. To…

The Millionaire Came Home Early — And What He Saw His Maid Doing With His Kids Made Him Cry CH2

Adrien Cole was one of the most powerful men in Texas. At forty, he owned skyscrapers, luxury estates, and a…

Just before our guests arrived, my husband sneered at me, calling me a ‘f;at pig.’ I held my tongue—but what I did next left him completely stunned CH2

The Saturday evening had been planned for weeks. Claire Bennett, a 37-year-old marketing manager in Seattle, had spent the entire…

End of content

No more pages to load