Part I

Seattle wore the morning like a fog-softened secret, the skyline peeking through wisps of silver as though the cranes and towers were shy. Scott Kramer adjusted his tie in the window’s reflection and caught his own eyes—tired but steady. Thirty-eight and the owner of Kramer & Associates, he had made a career out of anticipating how forces travel through steel and concrete, how a miscalculation today becomes a catastrophe tomorrow. He knew the language of load paths and lateral bracing, ground motion and failure modes. He knew how to keep buildings standing.

He’d been less successful at keeping his marriage from collapsing.

The phone buzzed across his desk. “Dad?” came the small voice that rerouted his bloodstream every time. Ten-year-old Lily—straight black hair she refused to tame, a dimple that showed up like a sunrise when she laughed.

“Hey, sweetheart. How’s the weekend with Grandma and Grandpa Spears?”

A pause. “It’s…it’s okay. When are you picking me up?”

“Tomorrow. Two o’clock, like always.” He heard something brittle under her “okay,” something that made his coffee taste like guilt. “Everything all right?”

“Yeah.” Another pause. “I just miss you.”

The line clicked off and left a quiet that pressed at his sternum. Since the divorce five years ago, weekends had become a grid on a calendar: color-coded blocks that pretended time was cooperative. Candy—Candace back when they met in grad school; Candy after she learned lipstick could be armor—had remarried quickly to a man named Lawrence Winn. Lawrence came with two eight-year-old twins from a first marriage that had ended with a drunk driver and a funeral no one liked to talk about. He also came with a father, technically a stepfather, named Jeffrey Petty, a construction magnate whose name was affixed to hard hats and yanked free from indictments.

Scott’s assistant knocked. “Mr. Kramer, your ex-wife is here.”

The click of Candy’s heels on hardwood never failed to make him think of verdicts. Auburn hair pinned like a strategy, green eyes that had once looked at him like a future and now looked past him like an obstacle. Marriage to Lawrence had added an edge—polished and sharp enough to cut.

“We need to talk,” she said, closing the door.

“About Lily?” he asked, because that’s what all his questions collapsed into now.

“About the custody arrangement,” she said, careful. “Lawrence thinks—”

“Lawrence thinks what, exactly?” His voice stayed even; his jaw did not. “Last I checked, Lawrence isn’t Lily’s father.”

Candy’s cheeks flooded. “He’s my husband, and he’s trying to build a family with his own children. It’s complicated. The twins…they need stability, routine. Lily disrupts that.”

“She’s ten,” Scott said. “Disruption is part of the job description.”

“You don’t understand the pressure he’s under.” Candy folded her arms; the diamond on her left hand flashed like an apology. “His father—Jeffrey—has very specific ideas about family. About bloodlines.”

The word sat on the table between them like a weapon. Bloodlines.

“Maybe,” she continued, eyes sliding away, “maybe Lily should spend more time with you. For a while.”

Relief flared, uninvited. More time with his daughter. More breakfasts with cartoon pancakes. More bedtime chapters, a flashlight tented under the quilt. But the relief faltered when he caught the flicker of panic in Candy’s eyes. She wasn’t offering him a gift. She was operating triage.

“What aren’t you telling me?”

Candy stood too quickly, the chair’s legs scuffing the floor like an accusation. “Nothing. Just—think about it.” She hesitated with her hand on the knob. “And Scott? It’s better if Lily doesn’t mention this conversation to Lawrence’s family. They’re…traditional.”

When the door closed, he watched his city through glass and tried to name the pressure he felt in his bones. In his line of work, he knew when a structure was under stress and the façade hadn’t caught up. He recognized hairline fractures before the cracks showed.

He picked up his phone and scrolled to a number he’d hoped he wouldn’t need again. “James? Scott Kramer. I need you to look into someone for me.”

James Jang’s voice, a quiet baritone: “Send me what you’ve got.”

The doorbell rang an hour early the next night. Scott wiped graphite from his thumbs—he’d been red-lining a set of seismic details—and peered through the peephole. Lily stood on the porch, backpack clutched to her chest like a parachute.

“Lily?” He pulled the door open, dropped to his knees, and felt the floor drop out from under him. A bruise spread from her left temple across her cheekbone, violet and ugly, partially hidden by hair someone had tried to arrange like a secret. He reached a shaking hand. “Sweetheart…what happened?”

She flinched and then stood very still, as if deciding whether to be brave now or later. “Nothing,” she said, the word small and unconvincing. “I just…I fell.”

“This isn’t from a fall.” He’d seen falls. He’d signed incident reports on a dozen sites: men walking backward into rebar cages, wrists bent under the laws of physics. He had learned to read injuries like blueprints. This one was deliberate. Fingers. A palm.

“I can’t,” she whispered, tears sliding, and the sight of them hurled him back to a delivery room ten years earlier where he’d held a newborn and promised a universe of things he had every intention of keeping.

“You’re safe,” Scott said, leading her to the kitchen. “You’re home. Are you hungry? Grilled cheese?”

She nodded, and he moved through familiar motions, butter and bread and a pan that hissed like a boundary. While she picked at the triangles with small, precise bites, he stepped into the hall and called the Spears’ house.

Lawrence answered on the third ring. “Winn residence.”

“Lawrence. It’s Scott.” He kept his voice low, the kind of calm that makes men admit things. “What happened to Lily tonight?”

A pause. “What do you mean?”

“She has a black eye. A bad one.”

“Kids get hurt,” Lawrence said. “That’s what happens when they don’t listen.”

“What exactly are you saying?” Scott asked, standing very still, as if motion could trigger a collapse.

“I’m saying your daughter needs to learn her place in this house,” Lawrence said, tone tightening. “My father was very clear about expectations.”

Scott’s grip whitened on the phone. “Your father, who is not your biological father, and has a last name that belongs on a hard hat more than a birth certificate, does not get to set expectations for my daughter.”

“He does in my home,” Lawrence snapped. “He doesn’t tolerate disrespect. Especially from children who aren’t blood family.”

The words found the center of Scott’s chest and detonated. “Did you just admit to hitting my daughter?”

“So what if I did?” Lawrence said, a smirk audible. “She ate dinner with my real children. She needed to understand the hierarchy.”

For a heartbeat, all Scott heard was air. He considered every way to end the call and choose violence. Instead, he let the chill flood back in. Cold was useful. Cold made things precise.

“Lawrence,” he said, each syllable like a bracket. “You just made the biggest mistake of your life.” He hung up and dialed again.

“Child Protective Services,” a woman answered.

“This is Scott Kramer,” he said, the words steady because they had to be. “I need to report child abuse.”

An hour later, CPS sat at his kitchen table taking photographs and notes, their camera shutter clicking like a metronome for the most important story he would ever tell. Lily, brave and trembling, whispered the truth to a stranger with a kind face: how Lawrence had slapped her for sitting in the wrong place at the dinner table—a place reserved, apparently, for Jeffrey Petty’s “real grandchildren.”

When the social worker left with a promise that wasn’t good enough for Scott but would have to do for the night, his phone rang again. Lawrence, panicked now. “What have you done? They’re here with badges, with cameras. They’re taking pictures of everything. My father is furious. They’re threatening to remove all the children. Scott—make it stop.”

Scott looked at his daughter on the couch, asleep on her side, an ice pack nested near the bruise like a clumsy moon. “Lawrence,” he said, voice low and final. “I’m just getting started.”

He ended the call and walked back to the couch. Lily stirred. “Dad?” she murmured.

“I’m here,” he said. He meant it like a vow.

He had spent his adult life thinking about foundations—how you dig down until you find something that will hold. Tonight, he discovered he had a deeper footing still: a bedrock under the bedrock. Whatever came next—lawyers, threats, headlines—would break itself against it.

He dimmed the lights, sat vigil, and began to sketch the only plan that mattered: protect Lily, expose the men who thought bloodlines were an excuse for cruelty, and make the consequences stick. Buildings stood because someone had done the math. Monsters fell for the same reason.

Part II

James Jang slid a manila folder across the coffee shop table the next morning. He’d worked through the night. He always did when he smelled rot in a file. Mid-forties, a face that could pass unnoticed on any street, hands that had learned to lift prints off doorknobs and secrets off cell phones without getting caught—James had been Scott’s insurance policy during the divorce. Now he was something else: a lever.

“The Winn family is a tangle,” James said, tapping the folder with a forefinger. “But the root is Petty Construction.”

Scott opened the folder and met a man whose photograph could be used to demonstrate the word “imposing” in a dictionary. Sixties, square jaw, a gray mane no one dared joke about, hands that looked like they liked to squeeze. Jeffrey Petty, CEO of Petty Construction. Scott had seen the logo on job-site banners and cranes. He’d also heard rumors. In construction, rumor is currency.

“What’s the relationship?” Scott asked.

“Not blood,” James said, which was funny and not. “Jeffrey married Lawrence’s mother when Lawrence was a teenager. Adopted him legally. Built a dynasty around a man he can use.”

“And he’s obsessed with—what did Candy call it? Bloodlines?”

James smirked. “The irony is not lost on me.”

Scott flipped pages. Contracts, site photos, filings. “What about the company?”

“Publicly,” James said, “they’re the hardworking backbone of regional development. Privately…” He slid over a second stack—inspection reports, whispers from skip tracers, memos from city staffers who thought their emails were private. “Cut corners to win bids. Substandard materials. Creative friends in planning departments. Unpermitted changes to structural systems. There have been complaints—CPS-style ones, too.”

“CPS?” Scott looked up sharply.

James nodded. “About the household. Three reports in the last four years. Two from neighbors, one from a school nurse. All died quietly. The case numbers exist; the paper behind them doesn’t. Jeffrey has friends everywhere.”

Rage is a poor engineer—too much heat, everything expands and breaks. Scott forced himself back into the discipline that had saved jobsites from earthquakes and egos. “Show me specifics.”

James put a finger on a photo of an Eastside shopping plaza Scott had driven past a hundred times without noticing what held it up. “See that expansion joint? Looks like a decorative reveal, doesn’t it? It isn’t. Beneath it—they used cheaper rebar, thinner slabs, and didn’t tie the diaphragm properly.” Next photo, a mid-rise apartment building along the river: “Seismic retrofit—on paper only. The plates are undersized, the anchors too shallow. You get a five-point quake with a close epicenter, and you’re looking at a pancake stack.”

Scott felt his anger crystallize into something useful. “And Jeffrey’s trying to land the Metro Hospital expansion.”

James nodded. “Two hundred million. Petty Construction is the front-runner. Guess who else is short-listed?” He made a drumroll noise that would have been funny yesterday. “Kramer & Associates.”

Scott sat back. The pieces clicked into place with a violence that felt almost audible. A man who believed bloodlines were more important than safety codes. A business that treated earthquakes like rumors. A household where a ten-year-old’s face told the truth CPS had been asked to look away from.

James looked over his glasses. “What do you want to do?”

“Two tracks,” Scott said. “The one that saves Lily today, and the one that makes sure these men can’t hurt anyone else tomorrow.”

He called his chief structural engineer, Aaron Stone—fifty-something, meticulous, a man who could look at a wall and tell you what held it up, what it hid, and how it would fail if insulted. Within an hour, Aaron stood in the conference room surrounded by blueprints and a whiteboard that was itching for equations.

“Tell me I’m overreacting,” Scott said, pointing to James’s printouts.

Aaron studied them like they were a crossword his father had left him. He traced a finger along a column line, frowned, then circled the connection details. “These are dangerous,” he said, voice flat. “Not just ‘we’ll fix it on punch list’ dangerous—criminally negligent. Foundation depths are shallow in poor soils, seismic joints are decorative, and I’d bet my ACI card the anchorage schedules are a fiction. These are the kinds of shortcuts that don’t fail on sunny Tuesdays. They fail on bad days.”

“How many people work in that Eastside plaza?” Scott asked.

“A thousand, maybe more,” Aaron said. “Shop workers, retirees getting their steps, teenagers pretending not to see each other. They’re all trusting whoever built that place to have done the math.”

Scott’s phone buzzed: Dad, can I stay with you tonight? Mom and Lawrence are fighting again. He swallowed the flood of heat and texted back: Yes. I’m on my way.

“Pull every set of plans Petty has turned in for the last five years,” Scott said. “Find the inspectors we trust—the ones who got moved sideways when they wouldn’t play ball. I want documentation. Photos. Scans. If we’re going to move this slow train, we need weight.”

Aaron nodded. “You’re building a case.”

“I’m building a collapse,” Scott said. “Scheduled, controlled, and entirely legal.”

An hour after Aaron left, Scott’s receptionist buzzed. “There’s a Mr. Petty here to see you.”

Scott glanced at James, who simply raised an eyebrow. “Send him in.”

Jeffrey Petty entered the room like a man who assumes rooms have been waiting. He was larger than his photo suggested; wealth has a way of adding inches. He offered a smile that felt the way cold metal tastes.

“Mr. Kramer,” he said, taking in the team, the prints, the whiteboard math. “I think we need to have a conversation about your daughter.”

“My daughter,” Scott said, standing. “Is not your business.”

“That,” Jeffrey chuckled, “is where you’re wrong.” He spread his hands, magnanimous. “Family is my business. Preserving its order. Its lines. Your daughter is confusing my grandchildren about their place in the hierarchy. Lawrence has been patient.”

“Children don’t need hierarchies,” Scott said. “They need protection.”

“You architects.” Jeffrey leaned on the back of a chair like it was a lectern. “You think the world is built on codes and drawings. The real world is built on allegiance. On knowing who you answer to. Blood comes first.”

Scott stepped closer until he could smell the cologne crafted to smell like authority in a bottle. “If anyone in your family touches my daughter again,” he said, voice dropping, “I will destroy everything you built.”

Jeffrey’s eyes narrowed. “Is that a threat?”

“It’s a promise,” Scott said.

“You have no idea who you’re dealing with, boy,” Jeffrey said, the last word heavy with the disdain some men carry like a family heirloom. “I have friends in every planning office in this city. Every courthouse in this state.”

“Then you should have built better friends,” Scott replied.

For a flicker of a second, something like surprise crossed Jeffrey’s face. The eyes recalculated. The mouth resumed its smile. “Be careful, Mr. Kramer,” he said, and left a smell in the room that wasn’t cologne but the memory of arrogance.

James exhaled. “Well,” he said. “Diplomacy’s over.”

“Good,” Scott said. He pulled out his phone. “Let’s accelerate.”

That night, he picked up Lily from school instead of letting the usual shuttle deliver her to the Spears’ house. She climbed in with relief all over her face. “Dad, are you and Mom going to court again?”

“Maybe,” he said. He wanted to give her a world without courtrooms and the words “my client” and “your honor.” He wanted to build her a house where the only noise was laughter and the occasional pan dropped by a man who thought he could cook. “But no matter what happens, you’re safe with me.”

“Lawrence says you’re trying to steal me,” she said, tracing the seam of the car seat with a fingertip.

“Lily.” He pulled over and faced her. “Look at me.” She did, eyes big, bruise fading but present. “You are my real family. You’re my blood and my heart. No one—and I mean no one—gets to hurt you.”

She nodded, the brave little okay that broke him and built him all at once. “I love you, Dad.”

“I love you too, Lily Bear.” He pulled back into traffic, a new plan sitting next to the old ones in his head. Foundations, failure modes, bloodlines. Whatever language men like Jeffrey used to justify their cruelty would not save them from the math.

Part III

The Seattle Planning Commission rarely entertained drama beyond the occasional developer who thought floor area ratios were negotiable if your handshake was firm enough. But that Tuesday, the room buzzed with a frequency that made pencils vibrate. Petty Construction’s bid for the Metro Hospital expansion was on the agenda.

Jeffrey stood at the lectern, slides queued to show sunrise-lit renderings and bullet points about “safety culture.” He delivered his opening line like a man who believed gravity took direction. “Petty Construction has a proud history of delivering complex projects on time and under budget.”

Scott sat in the back row with a leather briefcase full of lightning. Anonymous packages had found their way to commission members’ mail slots that morning—courtesy of James’s route that avoided cameras and curiosity. Inside the envelopes: independent structural analyses, photos of spalled concrete and cracked slabs, copies of material specifications that didn’t match deliveries. The kind of evidence that makes inspectors sit up straighter.

Commissioner Donna Johnston raised her hand. “Mr. Petty,” she said, voice professional as a scalpel. “We’ve received concerning reports about the structural integrity of several of your recent projects: the Eastside Plaza, the Riverside Apartments.” She slid a packet across to the city attorney. “These reports indicate substandard seismic retrofitting, inadequate foundation work, and the use of materials that don’t meet current standards.”

Jeffrey’s confident face flickered. “I’m not sure what reports you’re referring to, Commissioner,” he said. Men who live in penthouses often forget the basement exists.

“Independent analyses,” she said. “Verified by our inspectors.”

Scott stood. “Commissioners,” he said, carrying the weight of his name to the front. “Scott Kramer, principal at Kramer & Associates.”

If looks could pour concrete, Jeffrey’s would have set. “What the hell are you doing here?”

“Exercising my right as a citizen to address public safety,” Scott said. He clicked the remote. The screen filled with a photo of a foundation crack that looked like a map of a bad decision. “Over the last month, my firm has conducted a comprehensive analysis of Petty Construction’s recent work. What we found is criminally negligent.”

He flipped through slides: seismic joints painted to look thicker than they were, rebar tied too far apart, anchorage details that would pull out like loose stitches when the earth rolled. He spoke in the language of engineers and of fathers. “In a moderate seismic event, the Eastside Plaza could experience a progressive collapse. That’s not a line on a slide—it’s a Tuesday afternoon where a thousand families wait for texts from people who won’t send them.”

The murmurs gathered and spread. Someone in the third row whispered the word “indictment” like it could be conjured. Jeffrey stood, breath hardening. “This is a vendetta,” he barked. “This man has a personal issue with my family.”

“The evidence is in the buildings,” Scott said, and handed USB drives to each commissioner. “Independent lab tests, photos, the original submittals, and the actual invoices. We’ve also filed with the State Building Commission and Labor & Industries.”

Commissioner Johnston nodded, face grave. “Given the severity of these allegations, we are suspending consideration of Petty Construction’s bid pending a full investigation.”

Jeffrey surged to his feet again, caught between roar and retreat. Scott stepped close enough to lower his voice to a whisper that would bruise. “Did you think I was going to stop with your business?” he asked. “Check your email when you get home. The IRS is very interested in under-the-table adjustments and cash ‘consultant fees.’”

“You’re bluffing,” Jeffrey hissed.

Scott didn’t blink. “And Jeffrey? Those court-mandated anger management classes Lawrence is taking?” He smiled without joy. “Funny thing about mandated therapy. Confessions have consequences.”

He walked out into a Seattle afternoon that felt new. The skyline hadn’t changed, but the way it stood did. His phone buzzed every few minutes. James: IRS audit scheduled. His lawyer, Kenneth Thao: Emergency custody hearing moved up—tomorrow. Opposing counsel is rattled. Detective Ro Murphy: SPD opening a file—threat assessment. Need to talk.

Murphy’s suit was the color of an overcast day; his questions the color of a gun barrel. He sat in Scott’s conference room two hours later, hat on the table like a promise to be honest.

“We’ve been sniffing around Petty Construction for months,” Murphy said, flipping open a folder thick with redactions. “The IRS got there faster. Your submissions to the Commission help. But that’s not why I’m here.”

Scott waited.

“Lawrence Winn is unraveling,” Murphy said. “He’s made statements—public ones, unfortunately—about what he’s going to do to you. To your daughter.”

“Is my daughter in danger?” Scott asked, already knowing the answer but needing the formality of the question in the air.

“We’re issuing a restraining order, and we’ll have patrol cars near your house and her school,” Murphy said. “But Mr. Kramer—desperate men do unpredictable things.”

“The men threatening us aren’t unpredictable,” Scott said, heartbeat deliberately slow. “They are very predictable. They think might defines right, and they’re enraged to discover the opposite.”

Murphy closed the folder. “I hope you’re as good at protecting people as you are at demolishing reputations,” he said.

“I design buildings that dance and don’t fall,” Scott said. “I can do two things at once.”

That night, he upgraded his home security system with a kind of joyless efficiency that felt like tying rebar in a storm. A second lock on Lily’s window. Two more cameras. A panic button near the bed. He drove Lily to school in the morning himself, watched her walk inside with a backpack too big for her shoulders and courage just big enough. In the rearview, Jeffrey’s threat echoed. In the side mirror, his own promise did too.

Candy called during lunch, her voice tight as piano wire. “He’s furious,” she said without names. “He blames Lawrence for being sloppy, says you’re going to regret dragging the family through the mud.”

“Blood doesn’t make a family,” Scott said. “Behavior does.”

“Please don’t do this,” she said, and he could hear the Candy he’d married swimming beneath the Candy who had agreed to be a Petty. “Please. There are jobs at stake.”

“There are lives,” he said. “There’s Lily’s life.”

She was silent long enough to convince him she’d hung up. “He hit her because she sat at the wrong part of the table,” she whispered finally. “Jeffrey told him the head of the table is for ‘blood.’ Lawrence told her—told me—that Lily needed to learn. I thought…he wouldn’t really—” Her voice broke. “I was wrong.”

Scott didn’t say “yes.” He didn’t say “I told you.” He said, “Tomorrow. Court. Bring whatever courage you’ve got left.”

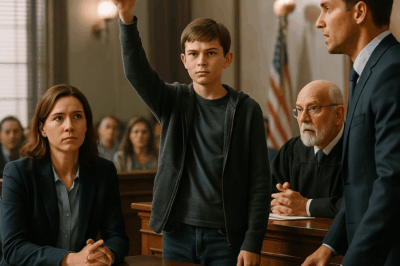

The hearing began with a gavel and the culture-shock of family law: men who spend their days reading seismic design manuals do not belong in rooms where your capacity is measured in tears. Judge Miriam Shelton looked at Scott over half-moons. She looked at Candy and saw what Scott saw: a woman who had set herself on fire to keep a bad man warm.

Before testimony began, commotion rippled through the hallway like a rumor. A shout; the sharp commands of security; a voice Scott recognized saying his full name like a curse.

Lawrence.

Detective Murphy materialized at Scott’s shoulder, earpiece glinting. “We’re handling it,” he said, but the word “handling” couldn’t hold what spilled through the glass. Lawrence, unshaven, eyes lit with something that wasn’t sanity, struggling against two deputies. “You destroyed my life!” he screamed, and the cameras did what cameras do—took a tragedy and made it public.

Inside, the judge’s voice carried steel. “Mr. Winn has been arrested for making criminal threats and violating a restraining order,” she said into the record. “This court considers that behavior in evaluating the safety of the child.”

Candy testified like a person at the bottom of a well. “I thought he’d be good,” she said. “I was wrong.”

Scott spoke last. He kept his voice steady, his gaze on the judge instead of the woman he had loved and the men he loathed. “Your honor, I don’t want to punish my ex-wife,” he said. “I want to protect my daughter. She came home with a black eye because a man who married into her life decided that blood buys the right to hurt. The family behind him believes the same. I build things that stand because I build them to stand. I want to build her a life that won’t fall when bad men push.”

The judge left and returned like a quick storm. “Full legal and physical custody to the father,” she said. “Supervised visitation to the mother in a neutral location.” The gavel fell. Ten minutes later, Detective Murphy pulled Scott aside again—eyes new serious.

“Lawrence posted bail,” he said. “Jeffrey still has cash. We’re keeping an eye. But…Mr. Kramer? Tighten your perimeter.”

Scott nodded once, a motion as small as a trigger squeeze. “I’ve got one more foundation to pour,” he said.

“What does that mean?” Murphy asked.

“It means I’m done reacting,” Scott said. “It’s time to control the load path.”

That evening he wrote an open letter and sent it to the Seattle Times. Architects don’t bluff about math. Fathers don’t bluff about daughters. The letter read like a blueprint for a trap.

To Lawrence Winn and the Petty Family.

You have threatened a child and called it honor. If you want to threaten me, do it to my face. I will be in my office tonight at 8 p.m., alone. Leave my daughter out of it. Bring whatever courage you can find. You’re going to need it.

He hit send, locked his desk, and waited for the weight to move where he wanted it.

Part IV

He hit “send” on the open letter at 2:17 p.m. and felt the city tilt a fraction, like a building settling onto its piers. Architects believe in cause and effect even when the inputs are made of people. You set loads, align your members, check your drift limits—and then you trust the math.

He did not trust men like Lawrence with anything, so he layered redundancy into the plan the way he would into a hospital: fail-safe upon fail-safe.

By 6:00 p.m., the 23rd floor of the Jackson Tower had been quietly repurposed from “principal’s suite” to “controlled environment.” James had seeded small pinhole cameras in the elevator vestibule and above the stairwell door, lenses the size of sesame seeds. The office’s own cameras—black domes in the corners—were integrated to a recorder that fed two encrypted clouds and a third drive in a locked drawer that could survive a fire. Murphy’s team staged two floors down, plainclothes and patient, a pair in the lobby nursing paper cups.

Scott did the only thing he knew how to do with time: he prepared. He walked the space like a superintendent before a concrete pour. He checked sightlines, tested the intercom, made sure the receptionist had gone home, checked the lock on the back stairwell twice. He texted Emma from three numbers she could verify without asking: Lily is at your place?

Fed, bathed, braiding her hair, Emma replied. She beat me at Connect 4 again, which I feel is evidence of a rigged system.

He smiled at the screen, real and brief. Read her an extra chapter. Tell her the building dances, but it won’t fall.

Copy. Go build the right kind of trap.

He stood at the window for a moment and looked out at the scaffold of his city. The Space Needle poked the sky like a joke that had aged well. Ferries drew chalk lines across the water. A crane two blocks over slewed, heeling like a ship, its hook a pendulum over a pit that would become condos or dreams. He could have sworn the skyline breathed.

At 7:52 p.m., James’s text: He’s in the garage. Dark hoodie. Alone.

Scott’s heart did what hearts do—forgot the math and leapt. He exhaled with practice. Breath in for four, hold for four, out for four, the way a therapist had once taught him when the divorce turned his nights into sirens.

The building’s security interface chimed. A badge had been used at the street door—a badge that wasn’t a badge at all but a quick piggyback behind a tenant who didn’t look. The lobby camera showed him in silver-gray: lank hair, the set of a jaw that promised ruin, eyes that were in the wrong room. He carried something under the hoodie that wasn’t a firearm but wanted to be bad news.

Murphy’s earbud twitched. “We see him,” he said into his sleeve, voice a calm river. “Let him ride.”

Lawrence stepped into the elevator like he was boarding a ferry to a better life. He pressed 23. The doors closed with soft regret.

Scott hit the intercom. “Come on up, Lawrence,” he said. “No detours.”

There’s a particular minute that lives between the twenty-second and the twenty-third floor—a minute long enough to make bad decisions or the right ones. Scott used it to press a recessed button under his desk; the button arced a signal to four devices that began to record independently. He took off his jacket, rolled his sleeves once—not to look casual, but because if blood was going to be let tonight, it wasn’t going to be his.

Ding.

The doors parted and the man who had slapped a ten-year-old child for sitting in the wrong place walked into the lobby of the man who drew lines for a living. Lawrence was not the polished version he wore for charity events and Instagram’s curated lies. He was unshaven, bruise-blue hollows under his eyes, a bat held not quite out of sight like he wanted someone to be fooled.

Scott stayed behind his desk, hands in view, a posture negotiated between calm and readiness. “Lawrence,” he said. “On time. I appreciate punctuality.”

Lawrence glanced at the corners, the ceiling, the glass. Paranoia is what you feel when you’ve finally come looking for a mirror. “You think you’re clever,” he said, the bat’s taped handle flexing under his grip. “You think you can take my family, my job, my father—”

“Your father?” Scott tilted his head. “The man who adopted you because you fit his idea of ‘son’ the way rebar fits a pour? The one who cuts corners in buildings and people?”

“He made me,” Lawrence spit, stepping forward. “He made all of this. He made me a man.”

“He made you a man who hits children,” Scott said, the drip of disgust calibrated. “That’s not making anything. That’s failing.”

“My real children,” Lawrence said, neck tendons like cables. “My blood. Your…your brat sat at their place. At my father’s table. She needed to learn.”

Every camera caught the sentence. Language has mass; that one landed like a beam. Scott had never been so grateful for physics.

“You came here to recite the same catechism?” Scott asked. “Or did you come to make the mistake that keeps men like you off the street for a very long time?”

Lawrence raised the bat an inch. A warning. A prophecy. “You took everything from me.”

“I turned on the lights,” Scott said. “You didn’t like what was in the room.”

“You destroyed my life,” Lawrence said, voice cracking with that particular blend of self-pity and rage that comes when power goes missing. “You’re going to pay for what you did. And then I’m going to find your daughter—”

“Stop.” Scott’s voice carried the weight of a beam settling. Not loud, not dramatic. Final. “The moment you make that threat, every judge, every juror, every cop in this city stops seeing you as a poor, misunderstood man and starts seeing you as what you are: a danger.”

“What are you going to do?” Lawrence sneered. “Call your cop friend? Hide behind paper?”

Scott pressed a key. The wall screen bloomed to life and showed Lawrence from four angles: the elevator vestibule, the office doorway, the camera over the reception desk, the one tucked into the soffit. Lawrence’s bat hung in the frame like an exclamation point.

“Here’s what I’ve done,” Scott said, the even tone of a man explaining shear walls to a city council. “Those cameras have recorded you since you came into the building with a weapon. They recorded you making criminal threats, including a threat against a child. They recorded you trespassing, violating a restraining order, and they recorded you saying the quiet part out loud about bloodlines. Every byte is mirrored to three places you can’t reach, and a copy of this feed is on its way to a judge who didn’t like you when you were clean-shaven.”

Lawrence’s eyes darted to the corners, to the screen, to the glass. His brain clawed at retreat, at reframe, at “we were just talking.” In its absence came the old song: violence.

He swung.

Bats don’t whistle in real life. They thud. The first hit took the edge of the desk and exploded a monitor. Scott stayed behind the desk, learned muscle memory kicking in: crouch, hinge, align, like setting a heavy vault door. The second blow he ducked by the width of a file folder. The third he didn’t let land, stepping in and trapping the bat’s handle under his forearm the way his krav maga instructor had drummed into him in a sweaty studio after the divorce. He twisted, not breaking, but making nice with pain. Lawrence made a sound like a stripped screw and let go.

“This isn’t over,” Lawrence said. He always needed to give last lines to bad scenes. “Family protects family.”

Scott heard the soft thud of fists on doors behind him—the entry team stepping into their blocking. Murphy’s voice, now in the room and not the ether: “Police! Drop it! Hands where we can see them!”

Lawrence looked at the gun muzzles leveled like horizontals in a frame and understood, finally, that this building had been designed to stand and he had been designed to fall. The bat clanged on tile. His knees hit carpet. Cuffs clicked, not unkind but unambiguous.

Murphy glanced at Scott, quick professional check: you good? Scott nodded. “Thank you for coming when the letter said ‘alone,’” Murphy murmured, dry as old plans.

“I program for redundancy,” Scott said, the adrenaline making his tongue lighter than it had any right to be.

“Winn,” Murphy said louder, addressing the kneeling man, “you are under arrest for felony harassment, making threats to kill, criminal trespass, and violation of a court order. You have the right to remain silent—”

Lawrence couldn’t help himself. “You can’t do this,” he said over the script. “You don’t understand who my father is.”

Murphy finished the Miranda like a prayer he’d said too often. “You have a right to an attorney. If you can’t afford one—”

“Jeffrey isn’t your father,” Scott said, too softly for the camera but not for the man on the carpet. “He’s your maker, and you mistook that for meaning.”

They took Lawrence away past the receptionist’s tulips, past the elevators with mirrored steel that caught a reflection that would follow him to arraignment and into the fluorescent life that awaited him. The doors swallowed him whole.

Murphy holstered his sidearm with a motion that looked like the period at the end of a sentence. “You’re going to get heat for that letter,” he said.

“I wrote it for the record,” Scott said. The monitor smoked gently. The room smelled like ozone and bad ideas. “And for my daughter. So she knows how men who love her behave when someone comes looking to hurt her.”

“How’s your perimeter?” Murphy asked out of habit, out of friendship, out of a cop’s ancient need to count walls.

“Buttoned,” Scott said. “But I’m not home until the man who gave Lawrence permission to be a monster is under a heavier roof.”

Murphy’s phone vibrated. He read the screen and let out a low whistle. “Huh,” he said. “The heavier roof might be on its way. IRS just served Petty Construction. FBI’s white-collar team says hello. You poked the bear; the bear’s accountants have entered the chat.”

“Good,” Scott said. He looked at the broken monitor—glass a scatter of glitter over the plans for the new emergency wing. “Let’s make sure the next building we put our name on teaches this city the difference between ‘on time and under budget’ and ‘built to stand.’”

The next morning’s Seattle Times didn’t have to invent a headline; it wrote itself.

CONSTRUCTION HEIR ARRESTED AFTER THREATS AT ARCHITECT’S OFFICE; FEDERAL AGENTS RAID PETTY CONSTRUCTION

The internet ate it like pancakes. A photo of Lawrence in cuffs—cheeks gray, eyes unfocused—sat above a second photo of men in windbreakers hauling bankers’ boxes out of Petty’s headquarters. Talking heads on morning shows used the word “accountability” like they’d just met it. Someone photoshopped “BLOODLINES” onto a cracked concrete beam.

Scott read none of it. He buttered toast for Lily, poured her orange juice, and kissed her hair. “Extra chapter tonight,” he said. “We’ll see if the building learns a new dance.”

“Can we read the part where the windows make ‘shoosh’ noises?” she asked, approving of onomatopoeia as a technology.

“We can make our own,” he said, sliding the toast across. “We can make all of it.”

He drove her to school past the courthouse where, later that day, cameras would take pictures of a man named Petty entering a building that did not belong to him and exiting much smaller. He made three calls at stoplights—Aaron, to check the status of the safety reports going out; Kenneth, to confirm the afternoon hearing details; James, to say thank you without saying thank you.

By ten, he was in Judge Shelton’s courtroom again, tie a little looser, relief held at bay until it was earned.

Candy was there, too, hair down for once, face five years younger now that sleep and remorse had finally called a truce. She didn’t sit near Jeffrey’s counsel. She sat in the row behind Scott, where Lily would be able to see her when supervised visitation started next week at the city family center with murals of animals who never yelled.

When the case was called, opposing counsel made noises about “overreaction” and “privacy” and “vendetta.” Judge Shelton let them finish the aria and then moved onto the work. “Mr. Kramer,” she said. “Any updates relevant to the safety of the minor child?”

Scott stood. “Yes, your honor. Mr. Winn was arrested last night for making threats against me and my daughter. Federal authorities executed search warrants at Petty Construction this morning. CPS has reopened prior files on the Petty/Winn household.”

She nodded. “The temporary orders stand. Ms. Winn, your supervised visitation schedule will be filed this afternoon. Mr. Winn, once arraigned, will have no contact whatsoever.”

The gavel made one sound and the scaffolding of a safer life slid into place another two inches.

In the hallway, Jeffrey waited with a face that had been carved by men who didn’t like him. The cameras didn’t love him anymore; they were bored by his suits. He stepped into Scott’s path because men like him can’t help themselves.

“You think you’ve won,” he said, that old sneer trying to find home.

Scott didn’t stop. “I know what I’ve won,” he said. “A table where my daughter can sit anywhere she wants.”

Jeffrey blinked, one beat late, then hung his mouth on the kind of sentence that ends careers. “Family protects family,” he said.

Scott let himself smile. “We agree,” he said, and walked past him to a day that had finally chosen a different script.

That night, when Lily fell asleep with a stuffed animal under each arm and the fan making the ceiling perform its lazy rotation, Scott sat at the kitchen table with a legal pad and wrote a list with two columns. On the left: what had been taken. On the right: what had been built.

The left column had its entries—sleep, ease, the soft belief that the world was gentler than it is. The right column filled like a permit board: custody orders, case numbers, inspectors’ reports, the text from Murphy that came in at 9:13 p.m., short and almost sheepish.

Winn remanded, no bail—flight risk. Petty indicted by feds on tax fraud + conspiracy. CPS closing the loop. Get some rest.

He stared at the words and let a thing he had not allowed since Lily had knocked on his door finally happen: he cried. Quietly, the way men who were taught to build their own bridges cry. He put his face in his hands and let the last week leave his body.

Then he stood, rinsed his glass, checked the locks—twice—and wrote one more line on the right, in ink:

We stood.

Part V

Three months later, Seattle’s winter light came down clean and decisive, like a layer of fresh primer on a wall that had seen things. The rain had learned to be polite; it stood in the street like a queue instead of a riot. The cranes were still at work, but their movement felt less like a gamble and more like choreography.

Scott held Lily’s hand as they walked into the new emergency wing of Seattle Children’s, the one his firm had muscled into existence after Petty Construction’s bid collapsed under the weight of its own shortcuts. The lobby smelled like lemon cleaner and new paint and a brand-new kind of relief. Above them, a web of buckling-restrained braces painted the precise red of a fire truck crossed the glass—no attempt to hide the skeleton here. Kids pointed at the diagonals and made “X”s with their arms. Somewhere, an engineer’s heart unclenched.

“Look,” Lily said, tugging him toward the dedication plaque by the elevators. The letters gleamed like a small, stubborn sun: KRAMER & ASSOCIATES EMERGENCY WING — BUILT TO STAND.

He had tried to say no to the naming but lost the argument like you lose to a tide. The hospital needed donors; donors needed plaques. He compromised where it mattered: instead of a list of rich names, a panel a few feet away explained base isolation in plain English with little diagrams of bearings that looked like donuts. A kid in a Spider-Man pajama top traced the arrows with his finger and nodded solemnly, newly fluent in the language of not falling.

Inside the wing, the choices were deliberate. The nurses’ station had sightlines to every bay. The backup generators lived on the roof, not in a basement that could flood. Pipes were hung on seismic springs; shelves had lips so teddy bears and syringes would not become projectiles when the earth decided to dance. The lights were bright without being cruel. Scott watched a nurse crouch to eye level with a child and point to the braces. “See those?” she said. “That’s our building’s superhero costume. Keeps us safe.”

Lily produced the kind of sigh ten-year-olds keep for things that impress them against their will. “Can a building be my friend?” she asked, looking up at him.

“If you treat it right,” he said. “And if the people who built it did the math.”

She nodded, satisfied, and skip-walked down the hall to the children’s room, where a volunteer sat with a stack of picture books and a laugh you wanted to take home. Scott leaned his shoulder against a column and, for the first time in months, let his internal inventory return with more credits than debits. No cameras. No courthouse. No plans to weaponize. Just a space that would do what it promised when a bad day came.

His phone buzzed, and he felt the old tension reach for his spine, but the preview loosened him instead:

MURPHY: SENTENCING IN 10. YOU COMING?

He typed: On my way.

He found Candy in the family lounge tucked near the vending machines, holding a paper cup with both hands like warmth depended on it. The supervised visits had been hard and good and necessary. She came on time, stayed present, never whispered apologies into Lily’s hair when the kid wanted to talk about school or cats or whether French fries counted as a vegetable. She learned to sit with discomfort, which is a kind of graduate degree.

“Hey,” she said, standing as if courts required standing even when they didn’t. She looked different—less lacquer, more person. Therapy had loosened her jaw. Leaving Lawrence had taken the rest of the weight that didn’t belong to her. “Thank you for bringing her here. She loves this place. She told me the braces are like a building’s bones, and I—” She laughed quietly. “I think she’s forgetfully teaching me how to be brave.”

“It’s a good place to practice,” he said. “Lots of proof around that the right choices hold.”

“I got a call,” she said, eyes flicking to the hallway as if a lawyer might materialize. “From the family center. If I keep showing up the way I have been, they’ll petition to transition to semi-supervised visits next month. At the park. With other people around, but—” She took a breath that traveled courage to face. “It felt…possible.”

“Good,” he said, meaning it. “That’s what this is supposed to be. Possible.”

She looked at him like she wanted to put her hand on his. She didn’t. Boundaries had become a language they shared now. “You’re going?” she asked.

“Sentencing,” he said. “I’ll text you.”

She nodded once, grateful without demanding his time. Progress measured in inches.

King County Courtroom 7B had the brittle hum of a place that had learned to host catharsis without indulging it. Rows of faces arranged themselves into teams. On one side, a few men in suits who would still say sir when asked for ID. On the other, union jackets from crews who’d lost jobs and found better ones after Scott had made calls and embarrassed companies into hiring right.

Lawrence sat at the defense table with a public defender who looked like she wanted to be in a different profession on a different day. He had shaved for the occasion or someone had shaved him. It didn’t help. He wore the defeated hunched posture of a man for whom a security door will always buzz. Scott experienced no satisfaction in the sight, which surprised him and then didn’t. Anger had done what it needed to do. The rest belonged to gravity and statutes.

The prosecutor recited the stack of counts like a grocery list—felony harassment, violation of a restraining order, attempted assault, obstruction. Murphy had prepared the court with the language of risk, the psychology report with the language of escalation. The judge, a woman with a patient mouth and impatient eyes, listened without blinking.

When she spoke, she did not perform. “Mr. Winn,” she said, “when a man makes threats against a child, he mistakes himself for a storm and discovers he is only weather.” She looked down at her notes, then up into the room where everyone had ended up who had failed to see the exit. “Twenty-five years. No possibility of parole for fifteen. No-contact order remains in effect at all times. Mr. Winn, you said once that family protects family. Consider this a lesson in what that looks like from the other side.” The gavel made a sound that was not triumph. It was relief wearing a robe.

Jeffrey’s trial happened in a different building with higher ceilings and more marble, because white-collar crimes are allergic to fluorescent lighting. On the first day, he walked in the way men walk when they are used to doors opening, and the camera caught the exact moment that habit fractured. Two weeks later, the jury took four hours to return with guilty on tax evasion, wire fraud, conspiracy, and two counts of witness tampering. The safety violations couldn’t be criminalized the way Scott wanted—statutes and thresholds always complicate justice—but the sentencing memo was laced with language that would make any developer who read it eat breakfast slower.

On the day Jeffrey stood to hear his number, his eyes found Scott’s in the gallery and searched for rage. What he saw instead looked like a building that had been retrofitted—same outline, different insides. The judge gave Jeffrey eighteen years and a fine that would require selling art he had acquired to impress men who would no longer shake his hand. When the bailiff touched his elbow to guide him toward the door that was not the one he’d used for thirty years, Jeffrey did not pull away. Even stubbornness has a weight limit.

Outside, microphones looked hungry, but Scott wasn’t in the market to feed them. He said the only sentence he wanted to live on the six o’clock news. “Family isn’t blood,” he said. “It’s behavior.” Then he walked away.

Work resumed in a way that felt like sleep after a long illness. Aaron brought him problems and solutions in equal measure. The city’s planning office began sending him tricky files—the kind that sat in drawers when inspectors didn’t have backup—and asked for expert letters. James, whose invoices were always an exercise in understatement, came by with coffee one morning and sat on the edge of Scott’s desk, quiet the way men are when they are leaving a room better than they found it.

“You did the thing,” he said.

“We did,” Scott corrected.

James gave him a look that said accepting credit is not arrogance. “Call me when you need me,” he said, which meant: I’ll be here before you know that you do.

At Kramer & Associates, the staff began joking that the firm had pivoted from architecture to civic immune system. The joke worked because it was true: blueprints can inoculate a city against a certain breed of lie.

Scott put that same ethic into his home—small, ordinary inoculations against the return of bad weather. Lily’s window had new sash locks and a view of a maple that performed a theater of seasons for her. The dinner table, which had once been a battlefield by proxy, became a classroom for inclusion. They rotated the “head” of the table because hierarchies don’t die easily; they need to be replaced with better games. On Tuesdays, Lily sat at the end and declared broccoli legal tender. On Thursdays, Emma sat there and called dibs on the last meatball whether she wanted it or not.

One Sunday, the doorbell rang at noon, and Scott opened the door to find his parents—the ones who had quietly struggled with his divorce, who had loved Lily with an uncomplicated ferocity since the day she arrived, and who had not known what to do with their son when he sharpened himself into something that could fight. His mother carried a pie she had not baked; his father held a toolbox because he never arrived anywhere without one.

“We thought the front gate hinge sounded loose last time,” his father said, which was how older men say we were worried and wanted to see your face.

They fixed the hinge. They ate the pie. Lily taught them how to play a card game where the rules changed midhand, which is a skill set every grandparent should practice. In the afternoon, they all walked to the park for Candy’s semi-supervised visit. Candy brought a kite, and Lily taught her how to run with the right kind of reckless. Scott sat on a bench with his father and watched the kite find a pocket of wind and stay there like a new thought.

“You did good,” his father said, eyes on the sky. It was not the kind of phrase the man used lightly. It landed where Scott needed it.

“I did what I had to,” Scott said.

His father nodded, which is how men agree when they are afraid their voice won’t hold.

On the day the emergency wing opened its doors to its first real patients—the kind who would not remember the ceremony but would remember the kindness—Scott brought Lily back to watch the ribbon cut. There was a podium because there is always a podium. A city council member said the words resilient and community and meant them. The hospital CEO said thank you in seventeen ways. Aaron said nothing and checked the slotted angles on a brace with his eyes because he can’t help himself.

When it was Scott’s turn, he looked at the scissors like they were a dare and then didn’t pick them up. He stepped to the microphone and told a small story instead.

“When my daughter was little,” he said, “she asked if buildings can be your friend. I told her, yes, if you treat them right. We built this wing in the open on purpose so you can see what friendship looks like when the ground moves. The braces out front are not decoration. The bearings under your feet are not indulgence. They are promises made into steel and rubber and bolts. And promises are only good if you keep them. So keep them with each other too. Be the brace. Be the bearing. When someone smaller sits at your table, make a place.”

He stepped back. The applause felt less like a storm and more like rain you can stand in without shivering.

That night, the dinner table at home featured spaghetti and meatballs, a thing Lily insisted was the appropriate meal for champions. Emma spilled a little wine and didn’t apologize. Candy came by after her shift at the nonprofit that had hired her to organize fundraisers; she stayed an hour and left before the conversation moved into zones that would require a map. The cat, who had never expressed an opinion on civic ethics, chose Candy’s lap for a full seven minutes. It felt like a vote.

After the dishes, Lily dragged a chair to the end of the table and climbed onto it with solemn ceremony. “I call this meeting to order,” she announced, because school had taught her parliamentary procedure and she was not afraid to use it. “I move that everyone can sit anywhere they want forever.”

Scott said, “Second.” Emma said, “Aye in the manner of pirates.” Candy said, “Aye,” and blinked the kind of blink that rewires memory. The motion carried, unanimous.

Later, when the apartment settled into the soft creaks that are the sound of wood forgiving weight, an alert rolled across phones and radios: a small tremor registered forty miles south, a shrug of the earth that rattled teacups and nothing else. In the new emergency wing, the bearings did exactly what they were meant to. The braces took the lateral load like professionals. A nurse steadied a cup for a parent and said, “Feel that? That’s the building doing its job.” Somewhere, a kid laughed—half scared, half delighted—at the soft shoosh the windows made. The power didn’t flicker. The lights didn’t swing. No one ran.

In bed, Lily rolled toward the wall, the way she always did when thunder sounded far off. Scott stood in her doorway and watched the ceiling fan keep its consistent lazy orbit. He let the adrenaline settle into a satisfied hum. He thought of the list on his legal pad and the line he’d written at the bottom.

We stood.

He padded to the kitchen, poured water, and paused at the refrigerator. Two photos held by a magnet shaped like a foolish carrot: on the left, Lily at three in overalls, fist closed around a dandelion like it was a wish she could keep if she held tight enough; on the right, Lily last week, mouth open to the rain, braces gleaming, eyes looking directly into the camera like she trusted the person behind it. Between them, a Post-it in his handwriting: Behavior, not blood. A reminder that held even when he was tired.

He returned to the doorway, listened to his daughter breathe, and finally let himself stop scanning the night for footsteps that would not come. Tomorrow would bring drawings and emails and city memos with typos. It might bring another fight in a different shape. But tonight, the math penciled out. The loads found the path he’d designed for them. The men who believed that might made right had discovered a new equation.

Seattle slept. The braces stood under moonlight like permanent applause.

Down the hall, his phone buzzed once, a final text before sleep:

MURPHY: Heard the wing shimmied like a ballerina. Nice job, architect.

Scott typed back: She danced. She didn’t fall.

He put the phone face down, turned out the light, and lay beside the life he had built with his hands and his anger and his love. The city breathed. The house breathed. His daughter breathed. The table would be there in the morning, and anyone could sit anywhere.

Clear as a gavel, quiet as a promise, the thought landed: the foundation held.

News

My Ex Told the Judge Our Son Wanted to Live With Him. Then My Son Pulled Out His Phone… CH2

Part I The courtroom was quiet, but not the kind of quiet that helps. It was the kind that made…

My Son Broke a Bully’s Arm. His Father Came For Me, Then I Said The One Word That Made Him Flee… CH2

Part I On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math. Two eggs, over easy. One travel…

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load