The Box on the Counter

The first time the phone rang, I thought the call had dropped.

It hadn’t.

“You gave them to Ruth,” Ezra said. His voice was different now—sharper, all the warmth scraped off the edges like burnt sugar from a pan.

“Yes,” I said slowly, the mug warm between my palms. “She’s always loved sweets. And I… well, I didn’t know what to do with them.”

He didn’t speak for a long beat. I could hear his breathing—tight, uneven—then the words came quietly at first, growing harder, like ice forming. “You did what?”

I blinked, startled by the slap of it. “I—Ezra, what’s wrong?”

“They weren’t for her,” he snapped. “They were for you. Only you.” His voice cracked—not with sadness, but something meaner. Frustration. Panic. I couldn’t tell.

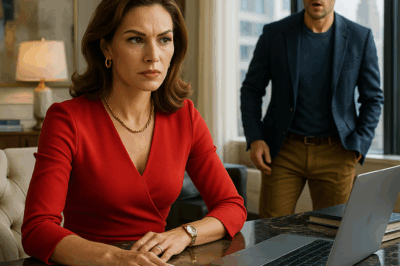

I sat frozen at the kitchen island, the coffee cooling in my hands. Only you. That’s what he’d said.

“I didn’t know,” I managed, my voice small.

“Right,” he hissed. “Of course you didn’t. You never do.”

The line went dead before I could find the next sentence. I lowered the phone to the counter and stared at the laminate pattern until it blurred. My heart thudded, not fast, but deep, like it wanted to be heard over everything else.

Only you.

I stood and walked to the fridge. The small container was still there where I’d left it after dropping the rest of the cookies at Ruth’s—one perfect star-shaped sugar cookie, untouched, nestled like it had been saving itself for me. I closed the door and suddenly felt cold, like the kitchen window had been left open in December.

That’s when the other phone rang—the landline in the hallway. Almost no one used it anymore. Its sound belongs to a different decade, the kind where you actually stood still to speak.

I lifted the receiver. “Hello?”

The line crackled, the way old copper remembers storms. “Marlene? It’s Laya. Ezra’s wife.”

“Yes?”

Her voice was brittle, stretched thin. “It’s Ruth. She’s in the hospital.”

I sat without meaning to, knees finding the chair the way your hand finds the railing in the dark. “What happened?”

“She collapsed this morning.” I heard the hospital behind her—the metronome of monitors, heels on tile, a cart squeaking down a corridor. “Vomiting. Disoriented. I thought it was flu, but it got worse. She couldn’t stand. She got confused. The ER… they can’t find anything definitive. They’re running tests.”

My mouth went dry. “Did she eat anything unusual?”

A pause that felt like it grew teeth. “She mentioned cookies,” Laya said. “Said you brought them over.”

“I did,” I said, the words thickening. “I gave her the box Ezra sent me.”

Silence. The kind that makes rooms tilt.

“Do you think they could have made her sick?” she asked eventually.

“I don’t know.” I looked at the fridge, at the memory of the container waiting in the cold. “I didn’t eat any myself.”

Another pause. “If you think of anything—anything at all—you’ll tell me.”

“Yes,” I whispered. “Of course.”

When I hung up, the house seemed to exhale and then hold its breath again. Late afternoon light had smeared itself across the living room and given up. I didn’t turn on the lamps. I didn’t move. I sat in the half-dark, watching the pattern of shadow on the wall like it had something to say.

After a while—minutes, hours, I couldn’t tell—I drifted back into the kitchen, a sleepwalker looking for a ritual to steady her. I opened a drawer, closed it. Straightened the dish towels. Wiped the already clean counter with a damp cloth because motion was a kind of prayer.

I pulled the trash bin out to empty it and saw something near the bottom—a small, clear plastic bottle, the kind vitamins come in. No label. Just a faint ring of white powder clinging to the inside wall, like frost on a window. I frowned. It wasn’t mine. I hadn’t seen it before.

I screwed the cap off. Nothing on the nose, just the sterile ghost of plastic. I put it down and opened the fridge. The cookie, star-shaped and sugared, sat in its little container like an idea that wouldn’t go away.

My hands shook as I lifted it out. I couldn’t look at the frosting without tasting fear. I carried both—the empty bottle and the lone cookie—into the study and set them on the desk. Under the lamplight, the sugar crystals sparkled. I folded my hands, knuckles white, and stared at them like I was waiting for a blink.

Was I the target?

Was it meant for me?

The questions were too big to touch.

Later, before bed, I called the lab where Janelle Marrow worked. We’d been neighbors once, the kind who exchange emails about package thefts and suggestion lists for better porch lighting. She owed me a small favor for keeping a hold on her Boston fern during a sabbatical year when it threatened to die twice.

“I need something tested quietly,” I said when she picked up.

She didn’t ask for details, just cleared her morning. “Meet me out back. Side entrance.”

When I hung up, the silence returned like a tide. I stood in the middle of the room for a long time and tried to imagine a different version of the last hour—a version where Ezra laughed when I told him I’d given Ruth his cookies, where Laya’s call was about flowers on sale at the market. The fantasy held for a moment and then snapped.

In bed, I didn’t sleep. The cookie stayed in the fridge. The dread stayed with me.

The lab was tucked behind a medical complex on the edge of town, the kind of low building that vanishes into parking lots. Janelle met me at the service door in a lab coat too crisp for the hour.

“This the kind of favor I’ll regret?” she asked with a half-smile that didn’t quite reach her eyes.

“Just tell me what’s in it,” I said. My voice didn’t sound like mine.

She nodded and disappeared with the container.

I sat in my car with the engine running and the radio off. My hands couldn’t get warm. I didn’t drive away. I watched the door swallow people and spit them back out—delivery drivers, a woman in scrubs, a man carrying a box labeled Reagents like it was a sleeping infant.

Memories seeped in like water under a door.

Ezra at eight, folding napkins at the dinner table into sharp triangles, then tighter triangles, then perfect geometric birds. Ezra at ten, erupting when I rearranged the pantry by color instead of size. Ezra at twelve, refusing to speak to me for a week after I bought the wrong brand of ketchup and not telling me why. Back then I called it “quirky,” “particular,” “sensitive.” Teachers called him brilliant. Other parents called him polite. On paper he was a model child.

I remembered, too, how he watched people eat. Not with hunger, but with attention. That time I accidentally baked with walnuts—he bit down, spat into the trash, and scrubbed his mouth until his lips went pink-raw. The stillness he mastered when he was disappointed, like he was storing the feeling for later.

My phone rang midmorning. A nurse from the hospital. Ruth’s condition hadn’t improved. They were escalating her case to Internal Medicine. Still no diagnosis. Still no timeline. No one mentioned the cookies, and I didn’t volunteer the idea. I promised to come later. I hung up and sat with a cup of tea I didn’t drink, the mug growing cold in my hands as the house made its familiar old-house sounds—settling, sighing, listening.

Ezra had always been good at the long game. He didn’t explode like some kids. He planned. He held. He looked at life like a chessboard and remembered where every piece had been.

When the phone finally rang again just after noon, I answered before the first chime finished.

“It’s Janelle,” she said. “We ran the standard panels, then… I told them to go deeper.”

I stopped breathing.

“There’s something in the cookie,” she said carefully. “Traces of a compound related to aconitum. Monkshood.”

I closed my eyes. My thumb found the edge of the desk and pressed hard.

“It’s highly toxic,” she continued. “Rare to find in food. This wasn’t an accident.”

“Someone ate these,” she added more softly, as if she could feel the crack forming across my chest from her side of the line.

I couldn’t answer.

“I’ll write it up quietly,” she said. “Do you want me to pass a note to a contact at the department? Off the record?”

I didn’t trust my voice. I hummed something that could be consent. We hung up.

My son had sent me poison wrapped with a birthday card.

Dusk came early and mean that day, laying a bruise across the sky. I paced the front walk with my coat open and no real reason to be outside. The wind carried a breath of cinnamon—or maybe that was the ghost of habit from years of baking snickerdoodles on Sundays when Ezra was small and forgivable.

Unknown number. My phone vibrated.

“This is Detective Fallon Reyes,” a calm voice said when I answered. “Are you Marlene Greaves?”

“Y-yes.”

“I was referred by Dr. Janelle Marrow. She said you requested a toxicology analysis on a food item and asked that any concerning results be shared with authorities. Is that correct?”

I wanted to say no, to pretend this was all a misunderstanding—that I was protecting something sacred and not rotten. But the word that came out was “Yes.”

A professional pause. Not unkind. “Would you be willing to meet to discuss the results and your concerns?”

Agreeing felt like signing a form I hadn’t read. “Okay,” I said.

The meeting wasn’t dramatic. No two-way mirror, no spotlight. Just a small office behind the station, four walls the color of oatmeal, a yellow legal pad, and a detective who looked too young for everything he already knew.

Reyes started soft. How long since Ezra and I had grown apart. How often we spoke. When the package arrived, how it was labeled, what it contained. How Ruth Langford came into the picture. I answered plainly, counting my breaths, measuring truth like medicine so I didn’t overdose.

He listened, eyes on me and the page both, and then asked the harder question.

“Do you believe your son meant to harm you?”

I looked at my hands—older than I remembered, a map of every year I had spent loving a person I didn’t fully know. “I don’t want to believe it,” I said. “But the cookie had poison in it. Ruth didn’t bake it. I didn’t bake it. He sent it.” I swallowed. “And the bottle I found in the trash—it wasn’t mine. The timing fits.”

“Any reason he’d want to harm you? Financial motives? Family tension?”

I flinched. “He resents me. Always has, I think. Blames me for things I couldn’t fix.”

Reyes nodded, but there was space between his eyes where doubt lived. All I had was a poisoned cookie and a mother’s instinct. No prints, no witness, no confession. When he leaned forward, his voice softened to match the place he was asking me to go.

“Would you be willing to submit the cookie and the bottle as evidence? Let us open a formal case.”

It felt like betrayal—even though betrayal had brought me here. Motherhood is muscle memory; it doesn’t forget the weight of a newborn because the boy got heavier. But memory isn’t justice.

“Yes,” I said finally. “If there’s any chance he’s done this before—or would do it again—I can’t ignore it.”

He stood. “We’ll log the items and keep you informed. If anything changes, call me directly.”

When I stepped back into evening, the parking lot lights had clicked on, cold moons in metal cages. I locked my car doors out of habit and sat with my hands on the wheel. It wasn’t guilt exactly, what I felt. It was something older and deeper—the knowledge that motherhood doesn’t end just because the child changes shape.

The part of me that had cut Ezra’s sandwiches into triangles now sat quiet and stunned, trying to square the boy with the box on my counter.

That night, I left the hallway light on and didn’t sleep. Every creak in the house pulled me upright. By morning, I had decided.

If Ezra didn’t want me to know what he was capable of, he should have been more careful. I would go to him—not as his mother, but as the woman he underestimated. And I would bring a recorder.

He answered the door with a smile that fit like a borrowed suit. “Mom,” he said, stepping aside. “This is a surprise.”

“Laya called,” I said, shrugging out of my coat. “I heard about Ruth. I wanted to check in.”

He nodded. “She’s still at St. Luke’s. They think it’s a virus.” He turned his face just enough to hide his eyes. “Laya’s with her.”

The phone in my pocket had been recording since I parked. His kitchen was the same altar to order it had always been: everything in its place, even the angle of the knife block. A home designed by a person who wants things to behave.

“I’m sorry we didn’t get to talk more the other day,” I said lightly, letting my gaze drift, counting. The plant on the sill was new. The spice rack wasn’t. “The cookies were lovely.”

He raised an eyebrow. “Were they?”

“I didn’t try them, actually. Ruth was thrilled. She said the star-shaped one was her favorite.”

There it was—the flicker. Barely a pause, but enough. His eyes narrowed, almost imperceptibly. His voice softened to something he thought sounded like sorrow.

“Ruth picked the stars.”

I hadn’t said what shape she ate, only that she liked one.

“Yes,” I said evenly. “She mentioned it.”

He turned to the sink and rinsed a clean glass. “Always did go for anything pretty,” he murmured. “More concerned with aesthetics than what’s underneath.”

I watched the line of his shoulders and thought of eight-year-old Ezra folding napkins into birds. “You never told me you’d started baking.”

He laughed. It rang wrong. “New hobby. Good way to unwind.”

“Where’d you learn to use monkshood?”

He didn’t freeze, not outwardly. But something shifted in his spine. A pause you could only hear if you’d taught him to tie his shoes.

“I don’t know what that is,” he said too quickly.

“Dr. Marrow does,” I replied. “She ran the test.”

He put the glass down carefully. “You went to Janelle.”

“She found it in the cookie.”

His mouth made a small shape. “Accusations like that…” He spread his hands. “They don’t end well without proof.”

“I think you’ve already given me enough,” I said quietly.

He stared at me for a long time. His face didn’t move. Behind his eyes, something did—a calculation I recognized from small-boy Ezra counting marbles, deciding which ones to keep.

“You’ve always misunderstood me,” he said finally.

“No.” I reached for my purse, keeping my hand steady while my heart pounded so loudly I was sure he could hear it. “I think I finally understand you completely.”

As I turned to go, my gaze snagged on the counter behind him. Half-covered by a tea towel sat another small bottle, identical to the one I’d found in my trash. Ezra saw the direction of my eyes and shifted his body casually, stretching to block the view as if boredom had taken him just then.

“I should go,” I said. “I’ve already taken up enough of your time.”

“Give Ruth my best,” he answered, voice light, false.

Cold air hit my face on the porch and shocked me into movement. I walked fast to the car. I didn’t stop the recorder until the doors were locked and the engine was running. I sent the audio to Detective Reyes before I could change my mind. Then I drove straight to St. Luke’s.

Ruth was unconscious. Laya sat vigil, eyes red-rimmed, body folded into the vinyl chair like a prayer. I told her what I had to. Everything. She didn’t ask for the details that would split her open; I didn’t offer them. We waited together in a silence heavy with beeping.

When I left, the sky had broken into a hundred shades of gray. That night, I made a pallet on the couch with a blanket and left the hallway light on. I slept in minutes, not hours. Every noise was a footstep. Every footstep was Ezra.

At 3:17 a.m., the phone rang. I was upright before the second tone.

Detective Reyes called just after sunrise. The audio was enough—paired with toxicology and Ruth’s chart—to convince a judge. They got the warrant. They took Ezra quietly before noon. He went like a man who’d rehearsed it.

I didn’t go to the station. There was nothing left to say that hadn’t already done its damage.

Ruth woke slowly, surfacing with confusion that melted into gratitude and then into a silence that knew more than it asked. I sat with her when Laya couldn’t. One afternoon, I took her hand and said, “I’m sorry.” She squeezed once. It was enough.

Later, in my kitchen, Laya cried. She said she should have known. Ezra had grown distant, strange. She’d found notebooks filled with precise notations—Latin names, dosages, solvent ratios. Mason jars of dried plants she didn’t recognize. She’d thought it was a hobby to keep his mind busy while work was slow. She’d been wrong.

Detectives would later show me printouts of Ezra’s posts on obscure herbalist forums under a false name—academic in tone, careful with his commas, clinical about extraction methods and interactions. Some of the phrasing matched Ruth’s bloodwork exactly. He’d been building this language for years like a second house behind ours, door locked, lights always off.

It all came down to one decision: one cookie I hadn’t eaten.

On a quiet Tuesday, I took the container from the fridge. The star had lost its shine, frosting dulled, sugar crystals gone to sleep. Detective Reyes had given me a sealed evidence bag after the arrest—“Not for revenge,” he’d said, “for clarity.” I slid the cookie inside, pressed the seal. It felt heavier than it should have.

I cleared a small fireproof box from the hall closet and placed the bag inside. Beside it, I laid the note Ezra had tucked into the ribboned box: Happy Birthday, Mom. Let’s start over. I locked the latch and set the box on the highest shelf—not to forget, but to remember what I had almost missed.

I stood a long time in the kitchen. The house held its breath with me. Then I turned off the light and walked down the hall, unsure whether it was safe to exhale—or whether it ever had been.

The Long Game

The morning after they took Ezra in, the house woke up before I did. Floorboards sighed. The radiator clanked a tired rhythm. I stood at the kitchen window with my hands wrapped around a mug I hadn’t yet filled and watched the street pretend nothing had changed. A dog tugged its owner; the recycling truck hissed and groaned; a teenager skateboarded past like gravity was a rumor. The ordinary world had the audacity to continue.

Detective Reyes called at 8:11 a.m., precise in a way that comforted me.

“We executed the warrant,” he said. “We found dried plant material, a mortar and pestle, tincture bottles, and notebooks. We also seized a laptop and two external drives.”

I imagined Ezra’s kitchen, the angles, the labels, the order. I imagined the tea towel half hiding the small bottle I’d seen. “What about the bottle on the counter?” I asked.

“Tagged. Same dimensions as the one you turned in.” He paused. “There was residue.”

“Did he… say anything?”

“He asked for a lawyer.” Another pause, a softer one. “That’s his right.”

Of course it was. Rights and wrongs ferry us to the same places sometimes. “What happens now?”

“Arraignment this afternoon,” Reyes said. “You don’t have to come.”

I heard the invitation behind the caution. “I’ll be there.”

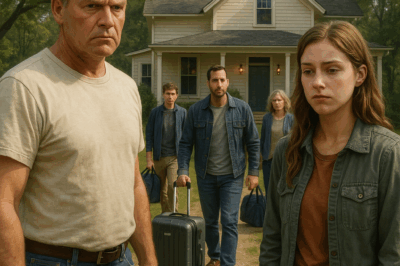

The courthouse smelled like lemon cleaner and old paper. Laya met me at the steps with a look I’d only seen once before—at her mother’s funeral, when the human face becomes a mask of effort. She wore Ezra’s gray scarf. It hung too long around her neck.

“How is Ruth?” I asked.

“Better.” The word carried relief and shame like a coin with two sides. “She’s awake. Foggy, but awake.”

We sat together in the back row. I’d rehearsed what to say, but small talk clatters in rooms like that. The lawyers drifted in with rolling suitcases and clipped voices. Someone dropped a pen; it sounded like a gunshot.

They brought Ezra in through a side door, the chain at his ankles short enough to make the walk awkward, long enough to preserve his dignity if you decided he still had any. He looked thinner under the fluorescent lights, a paleness that started from the inside. He scanned the room, found me, and the muscle in his jaw leapt like a trapped thing.

“State vs. Greaves.” The clerk’s voice turned names into case numbers.

The charges came like stones: Assault in the first degree, poisoning statutes that sounded medieval and current at once, attempted murder contingent on tests that were still at the lab. The prosecutor, a woman with hair so severely parted it looked like a wound, requested remand; the defense asked for supervised release. Words like flight risk and community ties ping-ponged across the room until the judge raised one hand. The gavel is theater; the hand is power.

“Remand,” he said. “No bail at this time.”

Laya’s breath left in a sound she didn’t mean to make. Ezra didn’t look at her. He looked at me. His mouth didn’t move, but I watched him shape the sentence with his eyes. Only you.

I turned away. Outside, the winter sun tried and failed to make warmth.

At the top of the steps, Laya stopped. “I don’t know how to do this,” she said, and the words were less a confession than a map of the air between us.

“You don’t have to know,” I told her. “You just have to keep putting one foot in front of the other.”

She nodded, then shook her head, then nodded again. “Ruth asked for you,” she said. “She thinks… she thinks your voice anchors her.”

I knew what she meant. Sometimes the person who carried the storm to your door is the only person who knows how to hold the door up once it’s blown off its hinges.

Ruth’s room was a box full of hums and beeps. She looked like someone who had been briefly erased and then penciled back in. When I stepped inside, she reached for me with a hand that shook from drugs or fear or both.

“I don’t remember,” she murmured. “I remember stars. And sweetness.”

I squeezed her fingers. “You don’t have to remember. You just have to heal.”

She nodded, then winced. “I was so unkind about your orange bathroom,” she whispered. “Back in July.”

It startled a laugh out of me. “It is very orange.”

“I wanted it to be lemon,” she said. “I wanted everything to be lemon back then. Bright and easy.” She closed her eyes, and for a second I saw the woman she’d been at thirty, hosting book club in a sweater set and pearls that I later learned were glass. “I’m sorry,” she said. “For being small when you needed big.”

“You never owed me big,” I said, and meant it.

On my way out, I ran into a doctor with the careful face of a man who knows the names of every system and still believes in luck. “Her labs are improving,” he said. “We’re lucky her dose wasn’t higher.”

Lucky. A strange word to wear.

Back home, the house felt like a witness. I walked from room to room, reciting a litany of what had happened where: here, the first time Ezra took his first steps between the coffee table and my knees. Here, the night he cried into my blouse because he’d gotten a 97 instead of 100. Here, the phone call in which my son’s voice turned from honey to blade.

I stopped in the hallway outside Ezra’s old room. On the top shelf of the closet sat a shoebox with a cracked lid and a greasy fingerprint on one corner. Inside: index cards with recipes written in my mother’s hand. Star Cookies. Molasses Men. Walnut Bars—I winced at the word—With Real Butter. The cards smelled like nutmeg and old paper. On the back of Star Cookies, in Ezra’s blocky fourth-grade scrawl: ONLY FOR MOM—then smaller, an arrow—(NO WALNUTS).

I sat on the floor and laughed until it turned into something else.

We think we are writing our children; then one day, we realize they’ve been annotating us the whole time.

The DA’s office wanted to prep me. “Not for trial yet,” the assistant district attorney said, “but for the possibility of Grand Jury. Clean timeline. No embellishments.”

“Embellishments are for cake,” I said before I could stop myself.

She didn’t smile. “Tell it to me straight, Ms. Greaves.”

So I did. I told her about the box on the counter and the call that didn’t drop and the word Only. I told her about the landline’s ragged voice and Janelle’s careful science and Reyes’ legal pad. I told her about the bottle in my trash and the bottle under the tea towel and the star cookie that refused to go stale.

When I finished, she closed her folder with an exhalation that sounded like relief. “It won’t be easy,” she said. “But it’s strong.”

Strong. A word with muscle. I wasn’t sure if I owned it yet.

Three nights later, an envelope slid under my front door with a sound like paper deciding to be important. No return address. No stamp. Inside, pressed and taped to a sheet of copy paper, was a purple flower, each petal thin as a whisper. Aconitum napellus, the caption read, in Ezra’s neat hand. Beneath it, three words: ONLY YOU, ALWAYS.

I sat on the steps and let the wall hold my weight. After a moment, I picked up the phone.

“He can’t send me things,” I told Reyes when he answered. “He can’t be in here.”

“He’s not,” Reyes said. “He hasn’t been released or transported.” I could hear his pen scratch. “Who has access to your door?”

“Everyone with legs,” I said. “It’s a house on a street.”

“Camera?”

“No.”

“Do you have the envelope?”

“Yes.”

“Bag it,” he said. “We’ll run it.”

I slid the flower back into its plain wrapping and sealed it in a Ziploc. Then I put the bag in the fireproof box with the cookie and the birthday card and the lock that felt more symbolic than useful.

I didn’t sleep that night. Out the window, the streetlights looked like moons chained to short posts.

In the morning, Laya called. “I found something,” she said without politeness. “In the attic.”

I was at her door in ten minutes. She’d pulled down a suitcase the size of a hope chest and dumped it on the dining table. Inside were notebooks, not delicate journals but cheap composition books with black marbled covers. Each was indexed with strips of tape and Ezra’s angular printing: EXTRACTS 1, EXTRACTS 2, DOSAGES, FAILURES.

“Don’t touch,” I said, then touched anyway—with two fingers, as if that made me cleaner. The handwriting was meticulous. The Latin names read like spells. Aconitum napellus. Atropa belladonna. Ricinus communis. Next to each entry were solvent ratios, temperatures, times, notes about yield.

There were also lists of usernames, login dates, forum threads with titles like Alkaloids in Historic Remedies and Micro-dosing vs. Fatality Thresholds. He’d been building a second language while we were busy trying to correct his first.

“Do you think he meant it for you?” Laya asked. Her eyes were rimmed with the red of someone who’d discovered that the person she married was a person she didn’t know.

“I think he meant for someone to be hurt,” I said. “Whether it was me or the nearest person to hand.”

She nodded and looked down. On the sideboard, a family photo in an oval frame caught the light—Ezra at eighteen in a mortarboard, both of us stiff with effort. I remembered the heat of the gym, the dean mispronouncing his middle name, the way Ezra held the diploma like it was the first piece of paper that had ever weighed something.

“Do you think I made him this way?” I asked before I could stop the question. The room didn’t offer an answer.

Reyes took the notebooks, the suitcase, and the list of usernames. “We’ll get warrants for the accounts,” he said. “If he posted under any of these, we’ll take screenshots, pull server logs if we can. The forums might fight; we’ll fight harder.”

“Someone left a pressed flower on my floor,” I told him. He nodded like he’d already positioned it on a mental board: pawn, knight, rook.

That evening, he called back. “We pulled a partial print off the tape on the flower. Not enough to run against AFIS, but it’s not yours or Laya’s. We also got a hit on a camera down the block. Hooded figure, 2:19 a.m. Waved something at your door. No face.”

“Ezra?”

“He was in custody at the time,” Reyes said. “But someone wanted you to feel seen.”

“I already feel seen,” I said. “I’d like to feel invisible.”

He exhaled softly, one human to another. “We’ll add patrols.”

A week later, the toxicology on the seized bottle came back with words only doctors love. Aconitine derivatives. Quantities that sounded small until you put them in a person. The ADA called to say the charges would be amended. The word attempted in attempted murder might be replaced.

I sat at the kitchen table with the index cards still out and wrote down everything I could remember that might matter to a jury who didn’t know us: Ezra’s kindness to the beagle that got loose on our street; the day he held Laya’s hair when she was sick and whispered in circles until she laughed; the fury in him that didn’t look like other people’s fury, the kind that goes quiet and takes notes.

It felt dishonest, trying to explain him without explaining me. So I wrote those things, too: the time I made the walnut cookies because I forgot he hated walnuts; the years I thought “particular” was a synonym for “fine”; the nights I watched him fold napkins too sharply and wondered if I was supposed to say stop.

On a Sunday, I went to the community garden where Ezra had once had a plot in the shade because the sunny ones filled fast. At the edge near the chain-link fence, a cluster of stems rose, purple hoods nodding. A hand-lettered sign read MONKSHOOD — DO NOT TOUCH. A laminated sheet below it warned of toxicity and included a paragraph about historic uses that made my stomach twist. Someone had thought the warning was enough. Someone had brought danger inside the fence and assumed the fence was wisdom.

I stood there longer than made sense. A father knelt nearby, showing his daughter how to pinch basil. The air smelled like chlorophyll and caution.

When I turned to go, a woman from the garden board appeared with a clipboard and concern. “You look pale,” she said. “Are you okay?”

“I am,” I said, and didn’t add: This flower almost made me a ghost.

The Grand Jury returned a true bill. The case moved forward the way rocks roll downhill. Ezra’s attorney filed motions, the judge denied most of them, granted a few that didn’t matter. They offered a plea; the ADA refused. Ruth agreed to testify if it came to it. Laya started seeing a counselor who specialized in what the pamphlet called “complicated betrayal,” which felt like naming a hurricane “wind.”

I waited. Waiting, I learned, is its own verb. It ends the day the thing happens, and then it starts again for the next thing.

One afternoon, the landline rang. I didn’t recognize the number, but I recognized the kind of silence on the other end—expectant, intimate. “Mom,” Ezra said.

“They told me not to take your calls,” I replied.

“You took this one.”

I should have hung up. I didn’t.

“They were for you,” he said. “The stars.”

“I know.”

“You gave them to Ruth.” He sounded like a boy telling on a classmate.

“I did.”

“You always give away what’s mine.” His breath hitched. “You gave away me.”

It took me a moment to find my voice. “That box was never yours, Ezra. It was a weapon.”

He laughed softly, the sound he used to use when I tried to teach him to parallel park. “You still misunderstand me.”

“I wish I did,” I said, and put the receiver back in its cradle like I was laying down a sleeping child.

I stood there a long time, listening to the landline hum. Then I walked to the fridge, opened the door, and stared at the empty spot where the cookie had been before it became evidence and then a story. I closed the door and pressed my forehead to the cool metal like it might bless me.

The house kept standing. The ordinary world kept its appointments.

I made myself a cup of tea with honey. I cleaned the mug I’d left in the sink. I sat at the table and copied my mother’s recipe for Star Cookies in my own hand, making small changes in the margin: less sugar, more lemon zest, no walnuts. I put the card in a new box—the one my granddaughter, if I ever have one, might someday open and ask about.

When she asks, I will tell her: this is how we learned that sweetness is not a synonym for safety.

What We Keep

The trial was still months away, but I had already started living in its gravity. Days felt longer, stretched thin by waiting. Nights were restless, even with the hallway light left on. I told myself I was safe—Ezra was behind bars, the evidence locked in boxes, the courts grinding toward their decision. But safety, I learned, wasn’t about locks or warrants. It was about trust, and trust once broken never stitched back neatly.

One morning, I pulled the fireproof box from the closet and set it on the kitchen table. Inside were the three artifacts that had come to define my new life:

The sealed evidence bag holding the single sugar cookie, star-shaped and dulled with time.

The pressed flower taped to copy paper, Ezra’s neat caption underneath.

The birthday card with its false sweetness: Happy Birthday, Mom. Let’s start over.

I laid them out side by side like a museum exhibit. Proof that the past year hadn’t been a nightmare. Proof that my memory hadn’t exaggerated. Proof that my son—my only child—had turned love into something toxic.

I should have hated him. Some part of me did. But hate was too clean. What I felt was heavier, like wearing wet wool in winter. I hated the silence he left behind, the questions that multiplied like vines. I hated the way I still looked at the phone sometimes, waiting for his name to appear.

That afternoon, I visited Ruth. She was stronger now, walking slowly down the hospital corridor with Laya at her side. She had color in her cheeks again, though her eyes still carried the fragility of someone who’d brushed shoulders with death.

“I remember pieces,” she told me quietly as we sat in her room. “The sweetness. The shape. Then the floor coming up too fast.” She touched her temple with careful fingers. “The doctors say my brain will fill in the rest, but honestly—I’d rather it didn’t.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, the words threadbare from use.

“You didn’t know,” she replied. “That matters.”

But I did know something, at least enough to suspect. And I had chosen silence until I couldn’t anymore. Her forgiveness felt like grace I hadn’t earned.

When I left, Laya followed me into the hall. She looked thinner, shadows etched under her eyes. “I found another notebook,” she said, voice low. “In the garage this time. He kept them everywhere. Like he wanted them to be found after.”

“After what?”

She shrugged helplessly. “After it worked? After someone died?” Her hand trembled as she held out a ziplock bag with the notebook inside, its cover smudged from years of use.

“Give it to Reyes,” I said, but my voice cracked. “Don’t open it again.”

Detective Reyes met me two days later in his office. He’d grown accustomed to my questions, my habit of folding tissues into smaller and smaller squares while we spoke.

“The new notebook adds to the pattern,” he explained, flipping through photocopies. “Same handwriting. Same compounds. A progression in experimentation—dosage notes becoming more precise, references to case studies. He even tracked news articles about unexplained illnesses. It’s chilling.”

“Was he always planning to use it on me?” I asked.

Reyes set down his pen. “I can’t answer intent. But the evidence shows clear preparation. Whoever the target, it wasn’t random.”

I pressed my palms together. “He wanted me to eat those cookies.”

“Yes,” Reyes said carefully. “And when you didn’t…” He didn’t finish. He didn’t need to.

At night, I found myself sifting through memories with forensic precision. Not the obvious ones—the first steps, the graduations, the smiles captured in photographs—but the small moments where something had been off.

Like the time Ezra, at twelve, watched me eat cake at a neighbor’s party, his eyes locked not on my face but on the fork. Or the day he erupted in fury when I gave away a pie we’d baked together, insisting it was his creation, not mine to share. I had brushed it off as childish possessiveness. Now I saw the early shadow of obsession.

What do we keep of our children? Their laughter, their drawings on the fridge, the curve of their baby fingers. But memory doesn’t let you choose. It keeps everything—the good, the wrong, the dangerous.

Weeks slipped into each other. Court dates were scheduled, postponed, rescheduled. The press sniffed around, hungry for the story of a poisoned cookie. Reporters called, emailed, even knocked on my door. I stayed silent. The only people I spoke to were Ruth, Laya, Detective Reyes, and my own reflection when I forced myself to look in the mirror.

Then one morning, I received a letter from Ezra’s attorney. Not a threat, not a demand. A request.

Ezra would like to see you. In person. At the jail.

I stared at the words until they blurred.

Why? What could he possibly want to say? Part of me recoiled at the idea. Another part—the part that still remembered tucking him into bed, smoothing his hair—ached to look him in the eye and ask the question that had gnawed at me since the box arrived: Why me?

I called Reyes.

“You don’t owe him anything,” he said firmly.

“I know.”

“Then why are you considering it?”

“Because he’s my son.”

Reyes sighed. “If you go, don’t go alone. And don’t go unprepared.”

The visitation room was smaller than I expected. A table bolted to the floor, two chairs, a glass panel dividing the room into mirrored halves. When Ezra walked in, I almost didn’t recognize him. The jail uniform drained the color from his skin. His eyes were darker, not from lack of sleep but from something deeper, like he was sinking inside himself.

“Mom,” he said, sitting down. His voice was softer than I remembered.

I didn’t speak. I waited.

“They weren’t supposed to hurt Ruth,” he said. “That wasn’t the plan.”

My breath caught. “Then who?”

His lips curved, but it wasn’t a smile. “Only you. Always you.”

The words slammed into me, even though I’d already known. Hearing them stripped away the last shred of hope that this had been a mistake, a misunderstanding.

“Why?” I whispered.

“You gave me life,” he said simply. “You should’ve been the one to taste what I made. Not her. Not anyone else.”

I stared at him, searching for remorse, for anything human. There was none. Just the cold logic of someone who believed their obsession was a gift.

“I loved you,” I said. My voice trembled, but it was steady enough to cut. “Even when you made it impossible. Even when you turned that love into poison.”

His jaw tightened. “You never understood me.”

“Maybe not,” I said, standing. “But I understand enough now.”

I turned and left. I didn’t look back.

That night, I opened the fireproof box one more time. The cookie. The flower. The card. Proof, evidence, relics. I thought about destroying them, about freeing myself from their weight. But in the end, I locked them away again.

Because sometimes what we keep isn’t about memory. It’s about warning. A reminder that even the sweetest gift can hide bitterness underneath.

And as long as I lived, I would never forget.

The Verdict

The courthouse was packed on the day the trial began. Reporters clustered on the steps like pigeons, their cameras clicking every time the heavy doors opened. I kept my head down, ignoring the questions lobbed at me: Do you believe your son meant to kill you? Do you have anything to say to Ruth?

Inside, the air smelled like varnish and nerves. Wooden benches creaked as spectators shifted. The jury box filled with men and women whose faces tried to hide the fact that they were already rehearsing how they would tell their families about this case: The one with the poisoned cookies.

When Ezra was brought in, chains clinking softly, I felt the same lurch in my stomach I had the first time I saw him as a newborn—fragile, unfamiliar, mine. Now he was still mine, but in a way I no longer recognized. His face was calm, eyes unreadable, posture straight as if daring the world to prove him wrong.

The Prosecution

The district attorney stood tall, her voice crisp as she laid out the case:

A birthday package sent from Ezra to me.

Cookies that carried not sweetness, but aconitine—monkshood.

The poisoned gift passed on to Ruth Langford, his mother-in-law, who nearly died.

Evidence recovered from Ezra’s home: dried plants, tinctures, notebooks detailing dosages.

The audio I had recorded, his slip about the star-shaped cookie.

The pressed flower, labeled in his own hand.

She spoke not with theatrics, but with precision. “The defendant weaponized trust,” she told the jury. “He wrapped poison in sugar, tied it with ribbon, and called it love.”

I watched their faces, saw shock flicker, saw some turn instinctively toward me in sympathy.

The Defense

Ezra’s lawyer, a man whose suits seemed to carry more starch than conviction, argued that it was all misunderstanding. That Ezra had been experimenting with plants for holistic remedies. That the notebooks were academic curiosity, not intent. That the cookie had been cross-contaminated, the poison introduced after the fact.

He gestured toward me once. “This is a tragic family conflict. Miscommunication. Misplaced assumptions. Nothing more.”

But his words floated thin in the heavy room. The evidence weighed more.

Testimony

When Ruth testified, her voice trembled but held. She described eating the cookie, the sweetness turning to nausea, the floor rising too fast. She described the confusion, the fear, the hospital lights. Then she lifted her sleeve to show the scar from the IV line. “I survived,” she said, looking at the jury. “But I will never eat without wondering again.”

Laya testified too, tears sliding down her cheeks as she described finding the notebooks in their attic, the jars of dried plants. “I thought it was a hobby,” she said, voice breaking. “I thought he was eccentric. I didn’t know it was… this.”

When it was my turn, the bailiff swore me in. I took the stand with my hands folded tightly in my lap. The DA guided me through it gently: the package, the call that hadn’t dropped, Ezra’s words—Only you.

“Why did you give the cookies to Ruth?” the DA asked.

I swallowed. “Because I didn’t want them. Because she has a sweet tooth. Because I thought it was harmless.”

“And when your son called you?”

I closed my eyes for a moment. “He sounded… disappointed. Not that Ruth had eaten them, but that I hadn’t.”

“And how did that make you feel?”

I looked at the jury. “Like my love had been turned into a target.”

Ezra Speaks

Against his attorney’s advice, Ezra chose to testify. He walked to the stand like he owned the floor. His voice was calm, his gaze steady.

“They’re painting me as a monster,” he said. “But all I ever wanted was to share something I created. Yes, I studied herbs. Yes, I experimented. But I never intended harm.”

He looked directly at me. “My mother has always misunderstood me. She sees danger where there is none.”

The prosecutor leaned in. “Mr. Greaves, do you deny writing Only you, always beneath a pressed flower of monkshood?”

Ezra hesitated. Just for a fraction of a second—but long enough. “It was metaphor,” he said.

The jury shifted. Doubt hardened into certainty.

The Verdict

The trial lasted two weeks. For me, it felt like years compressed into days.

On the final morning, the jury filed back in. The foreperson stood, paper trembling slightly in her hand.

“On the charge of attempted murder,” she read, “we find the defendant… guilty.”

The word cracked through the room. I felt it land in my chest like a stone and like a release all at once.

Guilty.

Ezra didn’t flinch. His jaw tightened, his eyes found mine, and for a moment I thought he would smile. But he didn’t. He simply sat, as if he had known all along.

The judge sentenced him to twenty years. The words fell like iron. Laya wept. Ruth closed her eyes. I sat still, hands clenched, the world tilting.

Aftermath

Outside, the reporters shouted questions again. I kept walking. What was there to say? That justice felt both too heavy and too light? That a prison sentence couldn’t undo a poisoned cookie? That I had lost a son long before the gavel dropped?

Back home, the fireproof box waited in the closet. I opened it one last time. The cookie, the flower, the card. Artifacts of betrayal. Proof of survival.

I placed the verdict slip inside with them, closed the lid, and locked it.

That night, I sat at my desk and wrote the first line of a new story:

Sometimes love is sugar on the tongue. Sometimes it’s poison. The difference is who you trust to bake.

For the first time in a long time, the words felt like mine again.

✅ THE END

News

I Discovered My Husband Was Planning a Divorce—So I Moved My $500 Million Fortune a Week Later CH2

The Whisper Behind the Door My name is Caroline Whitman, and for most of my thirties I treated happiness like…

My Best Man Slept With My Bride Pregnant the Night Before Our Wedding… I Exposed Them at the Altar CH2

The Eve of the Wedding My name is Scott Baker, and by the time I turned thirty-two, my life had…

My Daughter Took My Country House And Gave It To Her Husband’s Family. When They Arrived I… CH2

The House on the Lake I built my country house with my own hands.Every nail, every board, every stone in…

My Sister Stole My Fiancé—3 Years Later at a Family Dinner, She Froze When My Husband Walked In… CH2

The Moment I Stopped Breathing I used to believe there were two kinds of heartbreak: the kind you could see…

A little girl whispered, “Daddy is under the kitchen floor.” Minutes later, the police raided the house. CH2

In the leafy neighborhood of Maplewood Street, the days passed with serenity and harmony. Children played in their yards, neighbors…

Millionaire Opens Safe to Test Maid’s Daughter, but What He Finds Shocks Him… CH2

James Whitmore, a fifty-seven-year-old real estate magnate from Chicago, was known for two things: his sharp business instincts and his…

End of content

No more pages to load