Part I

On Maple Street, the morning always started with sunlight and simple math.

Two eggs, over easy. One travel mug of coffee. Fifteen minutes to beat traffic on the parkway. At 7:18 a.m., Alexander Landry—Alex to his neighbors, Landry to vendors, “Dad” in the only voice that mattered—tightened his tie in the hallway mirror and watched his reflection catch the calm he’d spent fifteen years practicing. A suburban house, white fence, a rose garden his wife tended like a second son. Perfection was fragile because it had been constructed, and he had constructed it.

“Dad, can you drive me today?” Bradley called from the kitchen. Voice bright, twelve years tall.

“Of course, buddy.” Alex set his briefcase by the door and stepped into a kitchen alive with the hum of a school morning. Meline stood at the counter, auburn hair pinned up, stack of baggies lined like a checklist. She sealed a lunch with the gentle efficiency of someone who had turned care into an art form.

“Don’t forget the conference next week,” she said without looking up. “Mrs. Peterson wants to talk about Bradley’s progress in Advanced Math.”

Alex ruffled his son’s sandy hair. “My boy. Numbers man.”

What none of the people who waved over hedges and said things like You’ve got it all, don’t you? knew was that Alex’s relationship with numbers had not always meant report cards and quarterly forecasts. Once, there had been other kinds of equations. The kind you solved in warehouses and back rooms and cars parked where streetlights didn’t quite reach. The kind that ended with a balance that stopped hearts.

He’d walked away when he met Meline, because some solutions aren’t tenable when a woman smiles at you like she believes your answer could be a life.

The drive to Riverside Middle School was twenty minutes of the easiest noise in the world: Bradley’s chatter about a science fair project that involved wind and a shoebox and a conviction that the word “renewable” could fix every headline.

“Kyle Hunter’s been weird,” Bradley said as they turned into the school drop-off. “Pushing sixth graders near the lockers. Trying to start stuff.”

Alex’s hands kept the wheel steady. “Kyle Hunter. His dad?”

“I don’t know. He says his dad’s scary.” Bradley shrugged the way boys do when they think shrugging makes them look taller. “Don’t worry. I stay away.”

“That’s good,” Alex said, every cell in his body remembering all the times he had chosen not to stay away. “But remember—never let anyone push you around. And if you can help someone smaller, you do it.”

He watched his son disappear into the brick building and filed the name the way he filed everything: carefully, with a folder title you could not read from the outside.

By noon, the consulting firm on the 18th floor of a glass box downtown hummed with a civilized kind of hustle: muted phones, a conference room calendar full of color-coded promises. Alex was reviewing a client’s Q2 misadventures when his phone vibrated. Meline.

He answered. The air around her name tasted like lemon cleaner and sunlight. But the voice was wrong—tight, shaky.

“Alex, something happened at school.” A breath. “Bradley’s in the principal’s office.”

He was in the elevator before the line clicked dead.

Riverside Middle wore institutional beige the way all such buildings do, another layer of paint over cinderblock that had already known more noise than quiet. Principal Janet Ross met him at her door, the kind of woman rumored to have learned patience from a decade of thirteen-year-olds.

“Mr. Landry,” she said, hands clasped like she needed the help. “There was an incident at lunch. Bradley… broke another student’s arm.”

Every old muscle in Alex’s body tightened in exactly the same order it used to when certain names walked into rooms. Calm came—the kind with edges.

“What happened?”

“Kyle Hunter was… bullying a smaller boy. Demanded his lunch money. When the boy refused, Kyle shoved him down and started kicking.” Principal Ross gestured through her office window. Inside, on a chair too big for him, Bradley sat with his shirt torn, a bruise rising on one cheek like a premature moon. He wasn’t crying. His eyes were defiant and clear, planted.

“Bradley intervened,” Principal Ross said. “Witnesses say Kyle threw the first punch at your son. The arm—” She hesitated. “Two fractures. Kyle’s at the hospital with his father.”

“His father?” Alex asked, and the floor under his feet turned to ice.

“Jerome Hunter,” she said, and the name was a church bell from a long-closed parish. “He… has a reputation. He’s called to demand Bradley’s expulsion. He’s threatening charges. He—” She swallowed. “He’s on his way here now.”

Alex stared at his son through the glass. It was a small mercy that Bradley looked like Meline. Sometimes there are things a boy shouldn’t have to inherit.

“I need to see my son,” Alex said.

Inside the office, Bradley stood when the door opened, an automatic courtesy that cracked Alex’s heart cleanly.

“I know I’m in trouble,” Bradley said before anyone could fill the space with words. “But Tommy’s little. Kyle was hurting him. He—he kicked him when he was down.”

Alex knelt so his eyes were level with his son’s. He put a palm on Bradley’s shoulder—the weight of a vow.

“You did the right thing.”

“But I—his arm—”

“Actions have consequences,” Alex said softly. “For everyone. Some of them might be loud for a while. It doesn’t change what’s right.”

Bradley’s chin lifted. “Kyle said his dad’s going to make us pay.” The word us landed heavier than anything else.

“Let me worry about dads,” Alex said. He squeezed once, stood, and turned back to Principal Ross. “What do you need from us?”

Before she could answer, Alex’s phone buzzed again—an unknown number. He stepped into the hall and answered without hello.

“Well, well,” a voice said, amused and choked on smoke. “Alexander… Landry. I heard you were dead.”

Hello, old life. He could hear his pulse in his ears like a forgotten drum.

“Hello, Jerome,” he said. “It’s been a long time.”

“You always did have good manners.” A snort. “Your boy cost me money.”

“Your boy was beating a smaller child.”

“My boy was training. He’s a fighter.” The word came out like a brand. “He was scheduled for the youth league next month. Prize money. Now his arm’s in a cast. Delays cost, Alex. I don’t give a damn why. I care about what. And what is—your family owes me.”

“Don’t do this,” Alex said, voice flat with control. “Not about kids.”

Jerome laughed, delighted. “Kids are business. This is my town now.” A click. Silence.

When Alex went back in, Bradley was watching him the way boys watch their fathers when they’re trying to understand the weather.

“Who was that?” Bradley asked.

“An old friend,” Alex said, and smiled so his son would not see the shadow. “Everything’s going to be fine.”

They waited in the principal’s conference room—high windows shadowed by blinds, a table that had hosted budget meetings and endless coffees. Principal Ross hovered like a woman trying to negotiate with a tide.

“There may be a way to… talk,” she said, voice hopeful and doomed. “Mr. Hunter’s the kind who—maybe a conversation.”

“I think a conversation would be good,” Alex said. He unbuttoned his jacket and, for a moment, let a part of himself he had learned to store away slide into his posture like a knife back into a sheath. He remembered how he used to open doors.

The black Escalade parked at the curb outside the school was theater. The two men in suits leaning against it were props. Inside the conference room, three silhouettes behind frosted glass were late for a play that had already been cast.

Principal Ross ushered the men in with a dignity that didn’t deserve who she had to share air with. Jerome had aged badly: scar tissue making topography where features used to live, hair prematurely gray, jaw clenched like it had chewed glass and decided to keep going. He looked at Alex and didn’t bother to hide the assessment, the small shock, the calculation.

“Alexander Landry,” he said, as if testing a counterfeit. “Or should I use the old one?”

“Alex is fine.” He gestured to the chairs as if they were in an actual meeting. “Jerome. Sit.”

Jerome didn’t. The two men flanking him—brothers by the look of their hands and their eyes—shifted into the kind of alertness that makes bad decisions look like loyalty.

“Your boy hurt my boy,” Jerome said, flat. “I’m here for a correction.”

“Your boy was beating a smaller child,” Alex replied. “My son corrected that.”

Jerome leaned forward on his fists. His hands were scarred in the way men’s hands get when they have fought things they should have walked away from. “Kyle’s scheduled to fight in three weeks. Two hundred grand, minimum. Do you know how long it takes to rehab an arm? Do you know what interest looks like on money I had to borrow because your kid decided to play hero in a cafeteria?”

Alex studied him the way he used to study faces for tells—a micro-twitch, an eye flicker—anything that revealed whether a man would panic or stall or pull a gun. Behind the anger, Jerome was hunting something else, too: history.

“You mentioned a youth league on the phone,” Alex said, careful because right now careful was a life jacket. “Kyle is twelve.”

“And the best.” Jerome’s eyes shone. Pride sat on him like armor he didn’t know was rotting from the inside. “He’s got hands like mine.”

Alex’s anger was cold, mathematic. He remembered rooms where grown men made money by watching boys bleed, and every part of him that had promised a wife and a backyard that he was not that man anymore had to grip something hard to keep from shaking.

“What do you want?” he asked.

“A lesson,” Jerome said. “Your boy gets expelled. You pay his medical bills, and a penalty for wasting my time.”

“Or?”

“Or I make your street less… pretty.”

The brothers’ hands moved toward jackets. The room got small.

Alex let out a breath, slow. He smiled, and it was the old smile, the dangerous one. It tasted like the first drink a man takes after swearing off whiskey.

“Jerome,” he said conversationally, “do you remember what I did before I bought a lawn mower?”

Jerome blinked. There it was—the flicker. “You consult now. For dentists and developers.”

“Before that.”

Jerome rolled a shoulder. “You cooked numbers for some suits.”

“Balanced them,” Alex corrected. “We called me the accountant.”

Silence is a weapon if you know how to draw it. The word hung between them—ordinary to most people, radioactive here. The brothers looked from Jerome to Alex, mouths going small.

Jerome tried to scoff. It sounded thin. “That was a long time ago. You’ve gone soft.”

“Have I?” Alex tilted his head, considering. “Tell me what happened to Vincent Carelli.”

Jerome flinched like someone had put a finger on a bruise he’d been pretending wasn’t there. Carelli was a story told in certain rooms to make certain men behave. Officially: a car accident. Unofficially: a warehouse outside Baltimore and a man who begged, and the accountant who did not believe in negotiating with mathematics.

“Car crash,” Jerome said, but the answer had the wavering narration of a man lying to himself.

“I remember it differently,” Alex said. “I remember him offering me everything—including his daughter—if I’d let him keep breathing.” He shrugged. “I’m sentimental, but I’m not stupid.”

The brothers’ eyes widened. One of them—Troy, if Alex had to guess from the way Jerome had shouted a name earlier in the hall—shifted his weight so his body angled instinctively away from Jerome. Predators don’t like to be prey-adjacent.

“Here’s what’s going to happen,” Alex said, voice quiet like a winter classroom. “You’re going to walk out of this school. You’re going to stay away from my son, and from the kid he defended. You’re going to keep your circus far from children who don’t choose to be in it. And if you don’t—if you even appear on the same block as my wife—” He let the sentence rest under his tongue a second longer. “I say one word in the right room, and you spend the rest of your life crossing streets you didn’t plan to, alone.”

Jerome’s mouth worked. “You can’t touch me. Daylight. Witnesses. You’re not a ghost anymore.”

Alex lifted his chin toward the frosted pane on the door. “Mrs. Chun in the main office has been recording for the last ten minutes. She thought it was… fair.”

Jerome spun. The silhouette of a small woman holding a phone was perfectly framed in the glass, patient, relentless.

“You’re bluffing.” It sounded like a prayer that wanted to be a dare.

Alex stood. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to. He picked up that old word and set it gently on the table between them where everyone could see it.

“Accountant.”

The air in the room changed temperature. The brothers swallowed. Jerome’s eyes—hard for an entire career—went soft around the edges. He took a step back before he remembered not to.

“This isn’t over,” he hissed, but his body had already gotten the message and was slowly trying to get it to his mouth.

“It is,” Alex said. He opened the conference room door and held it the way polite men do. “Walk away, Jerome.”

As the trio filed past, Alex heard it: the whisper he hadn’t heard since he renamed himself and learned where to put the mower in the garage.

“It’s really him,” Jerome muttered to Troy, fear finally locating his throat. “Jesus. It’s really him.”

Principal Ross materialized like someone who had been holding her breath since the first time she saw Jerome’s shoes scuff her tile. Her face was pale, but there was a calculation happening behind the shock—women who run schools learn to add while the room is moving.

“Mr. Landry,” she said. “Who… exactly… are you?”

Bradley watched them from the chair where he’d been drawing triangles on a legal pad while adults flirted with bad decisions.

“I’m Bradley’s father,” Alex said. He looked at his son, who looked back like he had been studying more than the lines on his paper. “That’s all that matters.”

He meant it. He meant it so hard it made his hands shake when he closed them a minute later in the hallway, out of sight.

But he also knew it wasn’t true enough. In certain circles, accountant wasn’t a job. It was a ghost story, an answer you didn’t want to show up on any of your tests. He had just put the word back into the air. Words don’t come back when you throw them like that. They find other mouths.

On the drive home, Bradley leaned his head back against the seat and said, “Dad?”

“Yes?”

“What’s an accountant?”

“A person who balances equations,” Alex said. It was technically true. “Why?”

“When you said it… Mr. Hunter looked like he was going to puke.”

Alex smiled, because this needed to be a story, not a scar. “Some people don’t like math,” he said.

Bradley laughed—the pure kind, 12-year-old air in it—and Alex swore to every god he didn’t believe in anymore that he would keep that laugh in the world.

That night, after Bradley was asleep and the house had returned to its normal sounds—the water heater’s polite cough, the neighbor’s dog commenting on the moon—Alex went into his study and sat staring at a locked drawer. He had left it locked for fifteen years because that’s what you do if you’re serious about being a different man. Inside were objects that did not belong on Maple Street: an old passport with a name that had helped him through airports you do not take pictures in, encrypted drives that could still rewire men’s lives if he let them, a photograph of five men outside a courthouse that history kept insisting had been properly recorded.

He rested his fingers on the key. He did not turn it. He looked instead at the pictures on the bookshelf: Bradley at six with popcorn stuck to his cheek; Meline at a beach in a sweater, hair blowing like a flag from a country he would always claim.

Meline tapped on the doorframe and leaned in. She could read him the way women read storms—what needed tying down, what needed to be brought in.

“Dinner’s ready,” she said, which was code for tell me what you’re not saying.

At the table, Bradley relived his day with the certainty of a boy who had discovered something about himself he had suspected and hoped for: he could be brave. He could be right.

“How was the meeting?” Meline asked, eyes on Alex over the mashed potatoes.

“It went well,” he said. “Jerome won’t be bothering us.”

She held his gaze a second longer than marriages require. “Are you sure?”

“Some men are all bluster,” Alex said. “When you stand up, they fold.”

It wasn’t a lie. It wasn’t the whole, either.

After dishes, after homework, after the ritual of a twelve-year-old’s bedtime (one more joke, one more reminder that nobody’s allowed to punch anybody in their sleep), Meline found him back in the study, the drawer still closed.

“This is about who you were,” she said, sitting opposite him. Not an accusation. A diagnosis.

“Yes.”

“Is he from that life?”

“Yes.”

She looked down at her hands. “Do I need to know more?”

“Not yet.” He swallowed. “But you might.”

Meline breathed in, out. “Then tell me one thing.”

“Anything.”

“If you have to go back there—even a little—can you come home from it?”

He thought of the word he’d said today like a password and the way it had opened a door to a room he had boarded up carefully with Sundays and yard work and the young ability to find wonder in the symmetry of a dinner table.

“I can,” he said. He reached across, took her hand like a petition and a vow. “I promise.”

Promises are just future math. He hoped he’d done it correctly.

On Maple Street, the night gathered up what the day had left out. Somewhere across town, a man who had learned the wrong kind of pride was planning a correction to his correction. Somewhere farther, in a warehouse with too much floor and not enough air, boys were being told that bleeding was a lesson.

And in a house with a rose garden and a boy asleep with his palm open on a pillow, a man who had once been a ghost and had become a father prepared—quietly, carefully—for a problem his neighbors would never believe existed if he described it on the sidewalk.

Outside the study window, a streetlight hummed. Inside, a locked drawer waited.

The word he’d said earlier in the day kept breathing all on its own.

Accountant.

It had made a bad man step back.

It had also woken something that didn’t like sleeping.

Part II

That night, Maple Street wore its usual disguise—a quiet cul-de-sac pretending bad things can’t find it on a map.

The dishwasher hummed. Meline graded papers with a red pen that left tiny comets in the margins of teenagers’ paragraphs. Bradley lay on the living room rug fashioning a wind turbine from straws and tape like he could coax a better future from what was at hand. If you squinted, it could have been any Thursday in any safe town.

My phone vibrated on the kitchen counter. Unknown number.

I let it go once, twice. The third time I picked up.

“Your one word,” the voice said, amused, as if we were trading trivia, “doesn’t work on everybody.”

“Evening, Jerome,” I said.

“You shook the Wilson boys,” he went on, ignoring me. “I’ll deal with that. But you don’t scare me, Alex. Not anymore.”

“You were scared enough to walk away from a public school in front of a principal and a camera.”

Silence. Then a smile I could hear. “You think daylight protects you. Daylight is just a curtain. Boys learn faster in the dark.”

The line clicked dead.

I stood at the sink a long moment, watching water bead on a plate and run down the slope into the drain. When I went back to the living room, Bradley had abandoned his turbine for a comic book. He looked up, mouth forming a question.

“Bed in five,” I said. “Brush with toothpaste, not bravado.”

He rolled his eyes and grinned like being twelve was a job with benefits. He kissed his mom’s head on the way to the bathroom. Meline waited until the sound of water started down the hall.

“How bad?” she asked.

“Not the worst I’ve seen,” I said. “Bad enough he called.”

“Will he come here?”

“He won’t,” I said. I didn’t add unless he’s stupid. Men like Jerome are stupid in bursts.

When the house was finally dark except for the small lamp in my study, I took the key I hadn’t touched in fifteen years and turned it in the lock.

The drawer slid open like it had been waiting.

I did not own trophies from that life. I’m not sentimental about what kept me breathing. I keep what’s necessary. A secure passport with a face I used to wear. Two encrypted USB drives—one with financial ledgers, one with favors—both labeled with stickers so boring they were invisible. A leather card case with numbers that had unlocked doors nobody admits exist. And a photograph of five men outside a courthouse that could have been any courthouse if you didn’t know why three of them were already dead.

The face next to mine in that photo—thinner, sharper, hungrier—still looked like a man who could do math in rooms where the air cost more. He would not have recognized my house—pictures on the wall, shoes in a basket, a boy’s paper airplane stranded on a bookshelf like a white flag. He would have pulled down the shades before he turned on the desk lamp.

I placed the drives on the leather blotter and opened my laptop. It felt like opening a window in winter. I typed a 36-character passphrase with muscles that had kept the sequence under my tongue for a decade and a half. The screen accepted me without comment, which is the best you can hope for from ghosts.

A secure call to a number that does not appear on any bill.

“Mr. Smith’s office,” a woman said. Her voice was the kind of neutral you learn when your job is holding a door to a hallway where names go to change.

“This is the accountant,” I said, and felt the old title fit like a coat you expect to be too small and discover still knows your shoulders.

A click. Then, “Well I’ll be damned,” the man himself said, amused. “The necromancers have been bored. We heard you retired to mow lawns.”

“I mow,” I said. “And sometimes I count. I need a favor.”

“Isn’t it funny you still call it that.”

“Let’s say I’ll pay later. I need quiet eyes on a man—Jerome Hunter. I want his debt tree, his payroll, his habits, and where he thinks he can hide. I want to know who he owes and how soon they come knocking.”

“Give me six hours for the bones and a day for meat.”

“You’ll have coffee,” I said. “I’ll have a list.”

I hung up and called a number that does appear on bills—Detective Ray Mitchell, a man who’d helped me build the bridge between who I had been and who I was now. He is as close as the law can get to a friend for someone like me without having to call Internal Affairs.

“Tell me you’re calling about bass fishing,” he said.

“Jerome Hunter.”

A noise like someone sitting down hard. Paper rustled. “I just poured coffee. Now I need something stronger.”

“He’s in town. His kid bullied a smaller boy. My son broke his arm stopping it. Hunter showed up at school with suits like it was opening night.”

“Jesus, Alex. He think he owns the place?”

“He thinks his name is still a warning. I used a different one.”

Mitchell exhaled. “Which one?”

“The one that made people cross streets.”

Silence on the line. Then, softly: “You sure you want that out there again?”

“He asked.”

“And you gave him the answer.” A sigh. “Okay. I’ll run him, quiet. But do not make me clean your prints off anything.”

“I’m just doing homework.” It was a joke. It wasn’t.

By morning, my phone had become a fact machine.

Smith’s first text: He’s leveraged. Six figures in juice to a local shylock called Red Manny, seven to the Khlov group (yes, those Khlovs). Youth fight circuits are the last revenue trickle. He’s desperate.

Mitchell’s call: “Word is he’s leaning on parents. Shakes the trees in neighborhoods where calling the police is either a joke or an invitation. A complaint came in yesterday from a woman we lost to ‘no cooperating witness.’ Name—Maria Martinez.”

“Tommy,” I said. “The boy Brad defended.”

“Yeah.” Paper rustled again through the line. “Hunter held a ‘meeting’ in a storage unit behind the tire place on Mill. Maria says he told parents the boys would ‘earn for the family’ if they shut up and signed on.”

“Where’s CPS?”

“Outgunned and underfunded. And scared. These folks disappear when they talk.”

“You know I’m going to—”

“Yeah,” he said, tired. “Do exactly what you do. Just try to leave enough for a warrant so I don’t have to pretend I don’t know you.”

By lunch, Principal Ross was calling again.

“Mr. Landry,” she said, voice trying not to shake itself into hysteria, “Kyle Hunter didn’t show. Neither did Tommy. And—” She shuffled, like she wanted to save the worst for last. “Sarah Chun. Her mother was at the desk crying. She said a man told her to keep her door closed today.”

Sarah. The receptionist with the phone at the glass. The woman who had recorded my conversation at the school. A knot formed behind my breastbone.

“Thank you,” I said. “Call Detective Mitchell. Tell him I asked you to and that he should call me back whether he wants to or not.”

Bradley came home quieter than the turbines on his shoebox could ever dream.

“Kyle wasn’t there,” he said. “Nobody would say why.” He looked down at his sneakers, then up at me with that unguarded brave the world keeps trying to pry out of kids. “Did I do this? Is this because—”

“No,” I said, fast, because that was the one knife I would not let him twist. “What you did saved a smaller kid from getting hurt again. What’s happening now is because a man refuses to act like a father. That’s on him.”

He nodded, mouth pressed flat. He wanted to believe me. He did. But the calculus of guilt isn’t taught in middle school. It takes adults years to unlearn.

After dinner, when Meline washed and I dried—a ritual, teamwork with ceramic—she said, “Say it.”

“I think Hunter grabbed his son and at least two others. He’ll train them where nobody knocks. He’s going to sell three and bet on one.”

“Jesus,” she whispered, a prayer and profanity in one.

“Ray can’t move without a tip and a warrant. Smith’s people found hints—rented space on the industrial side, cash changing hands through a fake gym. I can find the kids. I can get them out.”

“You’re asking me—”

“To let me be who I need to be,” I said. “For forty-eight hours.”

She looked at the window, at our backyard that had known only overwatered roses and inflatable pools. “Will you come home to me after seventy-two?”

“Forty-eight,” I said.

“You sound very sure.” She set a plate in the rack like she was setting a boundary. “I’m not going to sleep anyway, so… just tell me truth. All of it. The truth is the only thing I can carry without dropping it.”

“I’ll call you,” I said. “If I can’t, Ray will.”

She nodded. Then, to my surprise, she set the dish towel down and stepped into me, putting her forehead against my throat, breathing in like the scent of my skin was going to be what she would use to identify me at a morgue.

“Bring them home,” she said. “All of them.”

It sounded like a vow you make to your wife and to the world at once.

At 10 p.m., I parked a rental sedan six blocks from a warehouse that used to store textiles back when this city made things instead of swapping paper and angry looks. The building was thick with neglect—boarded windows, pigeons in the cornices, a chain-link fence that wanted to believe it was still a deterrent. An Escalade was tucked against a loading dock like a confession.

I climbed a rusted ladder to the roof of the adjacent building and lay down on gravel. The night smelled like dust and copper. Through binoculars, I watched men move with gait that tells you everything—loyal, bored, mean. Jerome’s silhouette flexed in and out of the light like a man trying to be bigger than shadows. A kid stood by a door in a cast—Kyle—jaw set, eyes darting to where his father stood every time the noise rose and fell.

Inside, I moved like a man who knew where the dark goes when the light changes. The side door was alarmed but the kind of alarm you could get at a hardware store. That meant a time delay and an exit not wired to a central station. A utility corridor ran along the back of a row of rooms designated with stenciled numbers. I put my ear to the metal of the first: snoring. Second: crying. Third: television—late-night kung fu, the kind of terrible taste men like Jerome think is style.

Room four: quiet. The quiet that means awake.

I picked the lock. It took eight seconds longer than I liked. Inside, a boy sat on a mattress on the floor, feet planted, shoulders squared. Tommy. His face showed the kind of bruising you get when someone uses you repeatedly to teach a lesson.

“Tommy,” I whispered.

He jerked, then stilled. His eyes—finally—recognized the shape of someone who had been a friendly face in a hallway.

“Bradley’s dad,” he said, somewhere between question and relief.

“I promised him I’d bring you home.” I motioned with two fingers. “Quiet and quick.”

He nodded hard, then pointed at the adjoining wall. “Sarah.”

“Okay,” I said. “We get her. Then we find the door.”

Getting out of the building is always easier than getting out of a life. We had to do both. I moved down the corridor, Tommy ghosting behind me with the focus of someone who is following the only adult he has decided to believe. Sarah’s lock surrendered faster—a cheap cylinder doesn’t care how pure your intentions are.

She was smaller than I’d braced for, hair muddied with tears. She blinked up at me like light hurt.

“Ms. Chun sent me,” I lied, because sometimes you pull a gentle name out of a pocket and use it like a key. “We’re going home.”

We almost made it to the stairwell before the first shout. A door banged open, and a man in a T-shirt two sizes too small proved that thickness is not the same as quickness. He reached for me; I stepped inside his grab and put him down with a move that made my shoulder ache with old arguments. He stayed where I left him, which is admirable in certain contexts.

“Run,” I told the kids. “To the alley, turn right, stay in the shadow. There’s a car with the engine on. You get in. If no car, you keep running until your legs tell you they’re done, then you get up and do it again. You do not come back for me.”

“Where are you—” Tommy began.

“I have to balance something,” I said. There are sentences you don’t ask children to understand.

They ran.

I took the stairs two at a time the way men do when the adrenaline writes IOUs their knees will have to pay later. The corridor flickered with fluorescent buzz, that old antiseptic hum I now only allowed to have space in hospitals and never in rooms like these. At the end, a door marked EXECUTIVE with tape.

I went in with my old name on my face.

Jerome stood by a desk like a man pretending to be a CEO in a bad movie. Kyle sat on the bed behind him, a brother-bear song stripped of melody.

“You,” Kyle said, a mixture of relief and dread.

“Me,” I agreed.

Jerome’s gun was out because of course it was. Men like him love the theater of power more than the work. “I told you daylight was a curtain,” he said. “You really came alone.”

“You always believed you were the headliner,” I said. “It’s one of your smaller mistakes.”

He flicked the gun at my chest. “Walk to the window and stay there.”

I did. I have learned that men with guns who think they own the room don’t like to be surprised by safety glass.

“I want you to watch,” he said, turning to Kyle with a grin he had practiced, I’m sure, as a boy in a mirror. “There’s only room for one hero. Yours doesn’t leave tonight.”

It is possible to be two men at once. I allowed a certain man to take my hands for three seconds. The one who had been trained to move when sound and light and angle lined up into a sum.

The first shot went into the wall because he flinched; I was not where I had been a second before. The second shot took the lamp. The third was mine. Shoulder. He spun. The gun fell. The brothers weren’t here—they had finally developed an instinct for self-preservation. The two guards behind him hesitated, the barest pause. It was enough. They dropped. Clean.

I kept the gun aimed at the floor and looked at the boy.

“Kyle,” I said, and tried to keep my voice from doing that thing grown men’s voices do around boys when they recognize something underneath all the stupidity—a kid who didn’t ask for this. “Your father is going to say you owe him. He’s going to call it loyalty. He’s going to say a man stands with family.”

Kyle looked at the blood on the floor and at his cast and at me. His mouth worked around something too big to swallow.

“Do you know what a man does?” I asked, and for a second I saw Bradley at my table eating cereal like he didn’t know the day would ever ask him for anything harder. “A man stands between power and the small. You have been on the wrong side of that equation. But you can change sides. Right now.”

Jerome groaned—shoulder wound whining, ego louder. He reached for his boot in a panic move men make when they think theatricality can outrun physics.

I did the work.

The room went very quiet.

Kyle stared at his father. He swallowed. “Is he—”

“Yes.”

There’s a kind of silence that lives only in rooms where choices have just been made. We stood in it. Then I moved.

“Come on,” I said. “Time’s yelling.”

Downstairs, the warehouse startled into chaos, delay between noise and action finally ending. We took the maintenance stairs, the ones a man uses when he doesn’t want to run into his coworkers. Outside, a car idled in the alley because sometimes people owe you and pay back on time. Tommy was in the back seat. Sarah sat in front, small hands folded as if prayer might be a seatbelt.

“Buckle,” I said. They did. I put Kyle in the back and got behind the wheel. “Keep your heads down. If I say bail, you bail.”

“What’s bail?” Sarah asked.

“Jump,” Tommy translated. “He means jump.”

We drove out into a city that thought it had seen everything. I made three lefts, two rights, and one noise that wasn’t words when someone blew a stop sign and almost put a minivan with a car seat into my lane.

I turned on a side street behind a 24-hour diner that had been innocently doing pancakes since the eighties. A staircase led to a door with peeling paint. I put a code in a keypad where most people see only a metal plate and the light blinked green. Inside, a living room with a couch and a lamp and a rug that had never done anything wrong waited the way rooms do when no one has asked them to hold trauma before.

“Sit,” I said. “Eat if you can. Water if you can’t. Toilet if you need. Don’t open the door. I’ll be right back.”

I went downstairs and handed the waitress at the counter a hundred and asked for four grilled cheeses and four milkshakes and the kind of look you give a man when he is very obviously paying for something other than melted cheese.

She slid the bag to me with a nod. “You look like a coach who forgot the orange slices,” she said. “Try not to get ketchup on your tie.”

Upstairs, I called Mitchell.

“I have three,” I said. “Fourth is upstairs with the last breath I’m willing to spend on his father. We need CPS here ten minutes ago. We need to lean on this so hard the floor creaks.”

“You—” He stopped himself. “Of course you did. I can get CPS and a couple uniforms without the press. Where are you?”

I gave him the address. “And Ray?” I said.

“Yeah.”

“It was him. I had to.”

Quiet. No lecture. “Okay.”

I called Meline.

“It’s done,” I said. “We’re at a safe place. Ray’s on his way. Don’t come.”

“I wasn’t going to,” she said. The smallest laugh, stripped of humor, pure release. “Bradley built a windmill that actually spins. I told him the power went out and his invention kept my lamp working.”

“That’s the best lie we’ve ever told.”

“It’s not a lie,” she said. “It’s hope with evidence.”

When the uniforms and the CPS workers came—tired, good people who had probably cried more than they told their bosses about—I sat on the stairs to the second floor with my head in my hands and let someone else do the talking. Kids went down the stairs in the arms of adults who were newly authorized to be gentle to them. Kyle came last, eyes on his shoes. He stopped one step above me.

“Tell Bradley I’m sorry,” he said. “And that Tommy didn’t pay. I made him give me the money and then I gave it back when nobody watched.”

“That’s not how apologies work,” I said. “You tell him. He’ll listen. He’s good at it.”

He nodded. “Are you coming with us?”

“I have to balance more,” I said.

He didn’t know what that meant, and yet he did. He went down the stairs into a future that would be messy and ugly and, if we were lucky, long.

Ray stood at the bottom of the stairwell and looked up at me with a face he reserves for evidence he can’t enter into trial.

“Gang war,” he said, deadpan, as if we were rehearsing a line for tomorrow’s paper. “Rivals shot Hunter in his own warehouse. Kids rescued after anonymous tip.”

“Anonymous caller used the word accountant,” I said.

He frowned. “You really want that floating around?”

“I will not be able to stop it now.”

“You know this means they’ll come lookin’ to see if a ghost is actually a man with a mailbox.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m counting on it.”

He blinked. Then nodded slowly. “You’re really going to—”

“I’m going to build something that drowns men who try to float on kids,” I said. “And if that means I have to wear an old coat sometimes, I’ll leave it on the hook by the door where my kid can’t see it.”

Outside, the sun was thinking about showing up. Maple Street was five miles and one lifetime away. I drove home with both windows cracked and the radio off and my heart doing the double-time thing it does when the body is offended by how much adrenaline it had to host. I parked in front of my house. The roses looked ridiculous, and I loved them more for it.

Inside, Meline leaned against the hall, hair down, eyes the kind of tired you can’t nap away. She took one look at me and accounted for all of it in a single breath.

“You came home,” she said, a fact that did the work of a thousand flowers.

“Grilled cheese,” I said, and held up the bag like an idiot.

She laughed, for real this time, the kind that puts years back in your body. She took the bag. She put it on the counter. She put her hands on my face like she was setting a bone. “This is going to keep finding you,” she said.

“I know.” I kissed her palm. “I think I know what to do about that.”

“What?”

“Make a door where it can knock properly,” I said. “With a sign that says: If you hurt kids, I will be answering.”

“You sound like a man applying for a government job he doesn’t want anyone to know exists.”

“Ray will call,” I said. “He’ll call because everyone else will be too polite to say they need someone who can do what I can do and still live in a house with a white fence.”

We stood there while the sun decided it was still interested in our street.

Bradley came down the stairs rubbing his eyes with the heels of his hands like a boy who still believed your face could be wrinkled from sleep. He saw me and stopped. Then he walked over like he had dreamed on purpose, put his arms around my waist, and pressed his ear into my shirt.

“You okay?” I asked.

“You?” he asked back.

“Balanced,” I said.

He leaned back. “Can we work on my windmill?”

“We can do anything you want,” I said.

He grinned. “Even pancake dinner?”

“We can even math that.”

The drawer in the study was closed by noon. Not locked, not yet. Some doors you keep close to hand for a while so you remember you can use them to get back out of rooms you had to go into when decent people couldn’t.

My phone buzzed. Ray.

“Coffee?” he asked.

“Always,” I said.

“I think I have a proposition you’re going to hate and accept,” he said.

“I’m listening.”

“Come in and consult. Quietly. Off-book. On the stuff we lose because we have to pretend broken things are rules and not excuses. You get intel. You get latitude. You get me standing between you and press.”

“And in exchange?”

“You stop pretending you retired from mathematics. You balance the ones that keep me up.”

I looked at my wife. At my son. At a house that had not once asked me to be someone I wasn’t willing to be.

“Bring donuts,” I said. “The kind with sprinkles. My team is very particular.”

“You don’t have a team.”

“I will by lunch.”

He laughed, a sound that admitted I wasn’t entirely joking.

When I hung up, Meline raised an eyebrow.

“So?” she asked.

“So,” I said, and felt something in my chest click into place like a column of figures finally agreeing, “I think I found a way to keep the door open without moving the house.”

“And the word?” she asked. The one I’d used that made a bad man bend his knees.

“It’s still the right one,” I said. “But now it comes with a different definition.” I reached for her. She came to me. “Accountant,” I said softly, like a word you teach a child, careful and precise. “A person who makes sure the math adds up to mercy.”

She kissed me. “That’s one I can live with.”

Part III

Ray brought the donuts, and the look on his face said he knew it was a bribe. He slid the box across the diner table like evidence and sat without waiting for permission.

“Maple frosted,” he said. “Because your street has ruined me for normal pastries.”

“You’re learning,” I said, and lifted the lid. Sprinkles. Law enforcement diplomacy.

We did the coffee ritual. Men of a certain age in American diners have fallen in love, divorced, and traded federal secrets over mugs like these. The waitress knew Ray’s name and pretended she didn’t hear mine.

“I can’t get a task force on paper for what you do,” Ray began. “I can’t requisition you. I can’t put your name on a board without writing myself into the kind of internal memo that ends careers. But I can say this: our job leaks. You can mop the floor faster than we can turn off the faucet.”

“Poetic,” I said. “Mopping is not my best metaphor.”

“You always were more of a knife block guy.” He leaned in. “You consult. Quiet. We bring you files when the ground under them is mud. You bring us places to stand. We do this clean. You don’t pull me into rooms where I have to un-see. We keep it for kids, for trafficked, for the cases that make decent cops go home and smile at their own children too hard.”

“And when I have to cross a line you can’t?”

“I don’t know about it,” he said. “Officially.”

“And unofficially?”

He looked down at the coffee and let a silence sit there until it smelled like agreement. “I sleep better if nightmares have names,” he said.

We ate donuts. We made a deal.

The first file he slid across the Formica looked like something that should have been solved in an afternoon: a mall abduction. Alexis Atkins, twelve, last seen near the food court under a banner that made bad grammar a corporate strategy. The mall’s cameras were there to catch shoplifters and teenagers holding hands, not hunting parties. The footage they had was a smear of pixels and the back of a man’s neck. Local officers did their rounds with the usual questions and came away with nothing but parents who’d learned how to cry without making sound.

I took the file home and laid it on the kitchen counter next to Bradley’s shoebox windmill. Meline came in, drying her hair with a towel, wearing the robe that made her look like the inside of a quiet morning.

“She’s twelve,” she said, skimming the photos. “What do you need?”

“A way in,” I said. “I need to know what kind of shop thinks it can set up in a suburb and steal kids under skylights.”

I called Cara Stewart, the Baltimore PI who had a habit of finding people who didn’t want to be found. Cara collects favors like some people collect stamps—portable wealth.

“Athletic Development Solutions,” she said over the line, after an hour in the darker parts of the internet. “Looks clean. Nonprofit filings. Training kids for ‘competitive sport discipline and character.’ Their board is a wall of polo shirts.”

“Who runs it?”

“A Dr. Clinton Spence. PhD in ‘Human Performance Science.’ Writes articles about grit he footnotes with his own hubris. He’s had three civil complaints from parents who say they couldn’t get their kid back. All settled under NDAs in counties where judges wear blindfolds and earplugs.”

“Front?”

“If it’s not,” she said, “then I finally have to admit humanity is irredeemable.”

By midnight, I had a cover identity—a wealthy nobody with an interest in “alternative youth athletics.” Mr. Smith’s network arranged the wardrobe and the jargon. My name for the day was Marcus Webb, and I had half a million in crisp bills that said I was serious about making bad investments.

Spence’s campus sat on the kind of acreage that corporations and cults favor—far enough from a highway to be quiet, close enough to a hospital to pretend to be safe. At the gate, men with clipboards tried to look like men with hearts. They checked my ID and my face and waved me in with smiles that wanted to be invitations.

Dr. Spence met me in a lobby designed by someone who thought corporate modern could make cruelty look clean. He wore a suit like a lab coat. His smile had been practiced in mirrored elevators.

“Mr. Webb,” he said, the syllables carefully calibrated to communicate money. “Welcome. It’s not every day we meet altruists.”

“Success requires sacrifice,” I said, choosing a sentence with enough buzzwords to be a passphrase. “Children today aren’t asked to do hard things.”

“Exactly,” he said, delighted. “You’ll understand, then, why some parents choose to partner with us at a deeper level. We provide an environment free from distractions—emotion, hesitation—so our athletes can achieve their potential.”

We toured polite rooms. Spence narrated discipline like it was a sacrament. Doors were reinforced. Cameras were everywhere except where real things happen. Staff moved with a tension you don’t learn in teacher training. The children we saw were the brochure kids—neat, silent, the blankness in their eyes the only sentence that told the truth.

“I’d like to see the training,” I said.

“Of course.” He led me into a gymnasium that had been converted into a small arena. Bleachers hugged a central mat. Adults ringed the margin with clipboards and cash. They watched children hurt each other. They cheered for elbow strikes. They wrote the future down in numbers on sheets that would become bank transfers and IOUs.

“That’s Stephanie Holden,” Spence said, as a girl placed a kick with surgical precision, then stood obediently while a man pressed a wad of paper towels to her opponent’s face. She was maybe twelve, but the part of her that looked out was older and tired. “Forty-three wins. Remarkable discipline.”

“How long has she been with you?”

“Parents entrusted her to us at nine. Aggressive tendencies. We gave them shape.”

“Entrusted,” I said, and smiled because I did not feel like breaking my cover by breaking his nose. “And the ones who don’t show promise?”

“Not every child is suited to elite training,” he said smoothly. “We have partners better equipped for those cases.”

Partners. Better equipped. He’d let the mask slip a fraction. The monsters always do when they believe you’re eating out of their hand.

“I’m prepared to invest,” I said. “But I like to understand the full mechanism of excellence. Including intake.”

He hesitated, then I opened the briefcase and showed him what made him brave enough to show me the truth. Half a million moves men toward honesty faster than ethics ever will.

We toured the intake building. Banks of metal benches. A tray of numbered bracelets. Staff in scrubs who had forgotten what being a nurse is for. And there—on a bench beneath a fluorescent light—the girl from the mall photographs. Alexis. Clothes that didn’t fit this place. A face that had been holding itself together all day and was running out of string.

“That one,” I said lightly to Spence. “Fast reflexes.”

“Promising,” he agreed. “We find it’s best to begin conditioning immediately. Delay breeds resistance.”

“You break them quickly,” I said.

“We help them let go,” he corrected, like all good liars.

I walked out with enough detail in my head to draw the building from memory and a fury in my chest that made my hands shake in ways Meline knows how to quiet. In the rental car, I called Ray.

“She’s here,” I said. “And thirty more. It’s not a warehouse. It’s a prison with a brand. He’s running full contact as curriculum. We need a warrant, a blackout, and rifles that can tell the difference between a child and a guard.”

“You have evidence that holds in court?” he asked, tired, doing his job.

“I have eyes and a girl with a birthmark on her chin who doesn’t know if she’s allowed to hope,” I said. “I can get you more. But if we wait for evidence to be palatable, conditioning begins at 0800.”

“Can you get inside, open doors?”

“Yes.”

He was quiet a beat. “You slow walk me the probable cause. I’ll start the machinery. I’ll call in favors. But you’re going to be there when the lights go out.”

“That’s the plan.”

That night, Meline sat on the edge of the bed and asked all the right questions. I answered with all the truth you can give a woman when you refuse to give her the worst thing: your body on a slab.

“Will you be in the room?” she asked.

“I will be a ghost in their wiring,” I said. “And when I need to stop being a ghost, I’ll be in a doorway with a gun pointing down, not at.”

She nodded. We have learned, over fifteen years, a language in which unthinkable things can be said without swallowing either of us whole.

I told Bradley I might be late to breakfast for a couple of mornings. He studied me with a preteen’s new suspicion that he’s not being told the whole story and a child’s old trust that what his father is doing is right.

“Is it like last time?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But bigger.”

“Do they have windmills?” he asked, squinting like he could insert a science project into a felony to make it comprehensible.

“They have kids who would like to see one,” I said.

“Okay.” He nodded seriously. “Then bring them here, and I’ll show them how to make the blades out of straws because it’s easier to spin.”

He went to bed because boys still have math quizzes even when their fathers are planning to unspool a nightmare.

I set the alarm for 2:27 a.m.

At 3:17, the generator blew the way I’d planned—loud like a warning, stubborn like an ulcer. Backup power kicked in, because Spence wasn’t sloppy. But he didn’t pay enough for his emergency electrician to be fast on switching the system from secure to safe. In that gap, gates thought they were doors, and we became people instead of paperwork.

I moved through the maintenance tunnel, breathing the hot metallic smell of old buildings and new crimes. The intake building’s lock was electronic and thus had the basic morality of a spreadsheet: it doesn’t care what you do, it only cares whether you do it correctly. I did.

Inside, the kids looked smaller than they had under Spence’s tour voice. Fear makes bodies fold. I knelt and put my hands where they could see them and used a sentence I have learned is the only key that works.

“My name is Alex,” I said. “I’m here to take you home.”

A boy with a shaved head and a scab on his lip said, “Are you real?”

“Yes,” I said. “And I brought grown-ups who have badges. But I need you to be very quiet and very brave for ten more minutes.”

“Are you a cop?” a girl asked, as if that were the deciding factor in whether she could move.

“I’m a dad,” I said.

They stood. They followed. Courage is often obedience in smaller bodies.

I radioed Ray. “Package One,” I said. “Seventeen kids to the east door. Alpha route. No lights.”

“Copy,” Ray said. “We’re up.”

While the extraction team shepherded children across grass toward vans, I went looking for doors that still needed opening. The dormitories had slid to manual locks when the generator hiccuped. My picks did their small, unromantic work. Faces looked out at me with expressions that tell a life. Some ran without being told. Some froze and needed a hand on an elbow and a sentence said twice. A few turned feral and swung, because you learn here that whoever opens the door wants to take something from you. I let them swing and then put my hands up, palms out, and learned their names.

Stephanie sat on her bed as if the floor were lava. I had watched her fight like a weapon. She looked like a discarded tool.

“You were watching me,” she said. “Yesterday.”

“Yes,” I said. “You were good at a thing you should never have had to learn.”

“My parents gave me away,” she said. “Because I was bad.”

“Your parents have been setting a place at the table for three years,” I said. “They didn’t stop. They just didn’t know where to set it.”

Her face changed in micro-motions—an expression I have never seen on an adult because adults learn to disguise the moment they decide to believe. She stood. “Okay,” she said, as if agreeing to put on shoes.

In the administration building, a tactical team used battering rams and the word police as a spell. Spence’s staff did not fight—they surrendered like men who had bet on the wrong concept of God. Dr. Spence himself barricaded his office with chairs. It was quaint. When Ray’s team peeled the door off its hinges, Spence tried to remember the script where he explains everything for the cameras.

He saw me. His face did something new.

“Mr. Webb,” he said, voice reaching for smooth and landing on sand. “This is a misunderstanding.”

“My name isn’t Webb,” I said. I took off the mask so he could see the face of a man he would think about at night in the time he had left. “You remember me.”

“You—” he stammered. His eyes did the math. “You’re him.”

“The accountant.” It came out quieter than I expected, and as soon as it was in the room, the officers in it understood a thing about me they could not put on a report.

“You can’t—” Spence began, defaulting to all the words men use when they have mistaken the architecture of the world.

“You’re going to do two things,” I said. “You’re going to tell these people with the guns exactly where your partners are. And you’re going to practice the art of shutting up when you’re done.”

“You—” he said again, this time with the edge of a plea.

“I’m a dad,” I said again, because it is a more complete truth than anything else I have ever told. “And you have been breaking children.”

He looked at the weapon on my hip. He looked at the badges behind me. He did the kind of math that saves lives because it keeps them in prisons instead of morgues.

“I’ll talk,” he said.

Outside, the sky was going the color of forgiveness. Vans idled. Children sat wrapped in blankets that smelled like laundry and government. A girl with a birthmark on her chin held a Styrofoam cup with both hands like it could thaw her future. Alexis.

“Are you the one who took the windmill?” I asked, squatting so my face was level with her idea of the horizon.

“I…I don’t know what that means,” she said, and her voice cracked because kids are allowed to be kids when the adults finally win.

“My son builds them out of straws,” I said. “He thinks everything can be convinced to turn if you ask it correctly.”

“Will I see my mom?” she asked, skipping over the metaphor the way you should at twelve.

“Yes,” I said. “Today.”

“Can I take the straw thing?” she asked, and pointed past me toward an entire life.

“Yes,” I said, because promises are math and I am careful about them. “You can have two.”

The radio on my shoulder crackled with Ray’s voice. “We’re green,” he said. “No losses. A few bruises. Spence is a fountain. We’ll be raiding six states by tacos.”

“I’ll bring salsa,” I said.

He laughed, and the sound broke something brittle in the morning.

On the drive back to Maple Street, I called Meline. “We’re bringing forty-seven kids home today,” I said.

“Forty-seven.” She said the number like it was a word she hadn’t gotten to say outside of a test in too long. “Come home to us after.”

“I will,” I said.

“And then what?” she asked.

“Then I stop pretending the only word I am is father,” I said. “And I make sure the other one knows who he works for now.”

“Accountant,” she said softly, and didn’t make it a threat. She made it a prayer.

Part IV

Three days after the raid, a cardboard file box the color of cheap oatmeal sat on my kitchen table like a dare. Inside: eight active abducted-child cases from three different precincts, a stack of NDAs Ray joked were “decorative,” and a burner phone whose number only five people on earth knew. On top, clipped to a manila folder, a brass plate someone from procurement had been too pleased with:

SPECIAL VICTIMS RECOVERY — DIRECTOR A. LANDRY

Bradley turned it over in his hands like a medallion you win at a fair. “Director,” he said, eyes wide. “Are you going to have a badge?”

“No,” I said. “I have a plate.”

He set it back on the table, reverent. “Can I bring it to school?”

“Absolutely not,” Meline and I said in a duet that made him grin and salute like we’d passed our first joint test as a paramilitary choir.

We rented two rooms in a nondescript building wedged between a bail bonds storefront and a yoga studio where people exhaled loudly about being alive. Room One was mine—desk, whiteboard, a coffee machine with a temper. Room Two was for the people who would do it with me: a systems analyst from city IT I stole legally by offering him a salary he couldn’t refuse and purpose he didn’t know he needed; Cara on retainer; two former CPS investigators whose burnout had been misdiagnosed as bad attitude; and a retired SWAT medic named Lolo who could calm a room with a look and fix a hole you never should have gotten in.

We did the only thing that makes any of this possible: we built a routine. Morning brief at 0800. Intel pass from Ray at 0900. Tumblers of coffee replaced by water after noon, because you cannot run on fire forever. We laid cases out on the board with string we didn’t need and used anyway because it makes your hands do something besides clench.

The first official case we picked up could have been a script from the worst corners of the internet: an illegal adoption ring laundering babies through a “charity” in the borderlands. The charity’s website had stock photos of women with scarves and sunlight and words like compassion in fonts so large they were alibis. The operation underneath had cargo vans and cash and paperwork created expressly to be shredded.

“What do we have that isn’t air?” I asked.

“Flight manifests,” the analyst—Sim—said, pushing up his glasses and pointing at a grid my old life would have appreciated. “Small municipal airport on the Mexico side. Private charters landing on Tuesdays. The passengers are always ‘medical staff.’ The paperwork is too clean.”

“Why Tuesday?” Lolo asked, tapping the calendar with a pen like he wanted to hurt it.

“Less federal staffing,” Cara said through the speaker. “And maternity wards discharge on Mondays.”

“Christ,” one of the CPS veterans—June—whispered, and wrote a list of names on a legal pad like she could bring them home by speaking them out loud.

We spun up quietly. Ray took the paper to a federal friend whose name came with an apology. Smith’s people got me numbers that aren’t public and confirmed what Sim’s eyes had already seen: a pattern that only exists when men are making money off other people’s grief.

The call that pushed us from planning into motion came at 2:07 a.m. from a woman named Elena who had been given a phone number by a social worker who had been slipped a Post-it by a nurse whose sister had once dated the analyst who now drank my coffee. It is a miracle anything lands where it needs to.

“They took my baby,” Elena said, words running into each other, breath hitching like hope was a hill. “They said she died—miscarriage—but I saw her. I saw her. They wrapped her and told me it was my mind. They said I was grieving wrong.”

“Where?” I said, the word as gentle as it could be and still be a knife.

She told me the hospital with a name that wanted to be a hymn. The doctor with a smile that wanted to be a god. The nurse who had said, in a whisper you only use when you’ve been caught with the truth, that there was a plane on Tuesday.

“Your baby’s alive,” I said, without hedging, because I needed one true thing to put in the room. “We’re going to make a lot of noise in very quiet places. Keep your phone on. Someone you trust is going to pick you up. You’re going to disappear from the people who lie to mothers.”

We put on our masks. Not literal—not yet. The ones where you put a rich man’s name on and ask a question through a gate. I became Marcus again for forty-five minutes on a line to a “philanthropic coordinator” who was very excited about my interest in funding “medical humanitarian flights.” By the time he finished telling me about the good we could do in the world, we had our Tuesday itinerary and the code a man at the airport would use to prove he was ours.

Ray got the warrant. The fed with the apology got the plane manifest. Lolo packed three trauma kits and said the kind of prayer soldiers say to a helmet when no one’s looking.

At noon on Tuesday, I stood by a fence that said NO TRESPASSING in faded red and watched a white Cessna taxi like a swan with teeth. The door opened. A man with a clipboard whose hair had never known rain checked boxes while others loaded a cooler marked with a blue cross and four small pink blankets nestled in a laundry basket that made my hands twitch.

“Ready?” Ray said through the tiny speaker in my ear.

“No,” I said. “Yes.” Both were true enough to power a building.

We moved. Customs swept the gate like a tide. The fed with the apology held up paper. Men in polo shirts tried to remember if they had lawyers. I walked to the plane, my old face and my new one together for once and both on purpose.

A man stepped in front of me, his chin up, the arrogance of immunity painted on his teeth. “You can’t be here,” he said. “This is a medical transport.”

He had the easy hands of a bureaucrat turned opportunist. His tie was expensive in a way I respect, because if you’re going to do evil, you might as well not look cheap. He put his palm out like he was stopping a salesman at a door. I did not stop.

“What are you,” he demanded, outrage turning the corners of his mouth white. “Who do you think you—”

“Accountant,” I said.

It takes a special kind of education to understand a word in a dialect you didn’t know you had learned. It didn’t matter if he had ever heard of me. The men behind him had. One of them—a pilot with a scar that ran into his hairline like a river and a run of bad luck—took a step back on reflex, heels hitting the wing strut. Another glanced at his phone like it would save him if he typed fast enough.

The man with the tie recovered, tried a grin. “We do books in-house,” he said.

“I do a different kind,” I said, speaking his language less and mine more. “Start with four babies and subtract your freedom.”

He blustered for two minutes while Ray’s people gently performed a miracle around him—opening coolers, checking pulses, calling names over a radio that belong to mothers and not to manifest codes. The bluster stopped when a noise no one should ever have to hear rose over the tarmac—the kind a woman makes when the thing she had convinced herself was dead breathes against her skin.

Elena ran with a speed grief had no right to have and a precision mothers always find. She took the bundle a federal agent meant to hand her like a gift you have to be careful with or it will disappear. The baby squalled. Elena wailed. A TSA agent with forearms like trees cried openly, badge shining like a ridiculous pin on a very human chest.

The man with the tie finally understood which way numbers go when you count like this. He bolted—not a graceful exit, not even a plan. He ran for the door he had come through because men like him cannot imagine the world does not belong to them. Lolo met him halfway and put a palm in the middle of his chest with the tenderness of a bouncer. He sat down unexpectedly, as if gravity had decided to stop taking bribes.

The paperwork snarled for days, because this is how evil stays busy—slowing you with forms after you have been very fast with courage. Elena disappeared to a safe place with her baby; the other infants found their way to arms that had been practicing the shape of them in the air for weeks. The man with the tie asked for a lawyer. He got one. Then he gave up names that filled a whiteboard wall.

I slept two hours in two days, then stood in my living room and watched Bradley pin a blue ribbon to a tri-fold display that said Harness the Wind: Renewable Energy for Everyday. He had written my name in the acknowledgments like I was a famous scientist.

“You didn’t have to,” I said.

“You showed me the math,” he said.

“What math?”

“If you make enough small things spin the right direction,” he said, “you can power anything.”

He’s twelve. He shouldn’t be allowed to be that right yet. But I advise no one to stop him.

Two weeks later we held our first interagency debrief with men and women whose jobs never make it into television shows because the hero shots would make the audience sad. Ray brought coffee. The fed with the apology brought donuts with no sprinkles, and I told him that meant he had to get stabbed during the next meeting.

We pinned names to maps: red string to warehouses, blue to courtrooms where we could still win, green to kitchen tables where a child would sit tonight who did not sit there last week. Spence’s information led us to places even he didn’t know he had been feeding—Kansas barns and Florida strip malls and a Colorado retreat with a view reserved for the wicked. We took them apart. We did it clean.

Some nights, the drawer in my study stayed half-open. I don’t lock it now; I keep it where my hand can find the tools if the day requires opening a door nobody wants to admit exists. Some days I shut it and go to Bradley’s soccer game and shout too loudly when he passes instead of shoots because balance is not always about goals. Some mornings, when the news is full of things we cannot fix with string and a blender’s worth of tape, Meline stands in the doorway of the kitchen and watches me put my tie on. She tilts her head, smiles at how ridiculous we look playing family, and reminds me this is the point.

We are getting a reputation—quiet, inside the rooms that have keys. Sometimes the phone rings at midnight. Sometimes it rings at noon. Sometimes, like a storm you have been watching on a radar, it arrives right over the place you promised yourself was too small to be noticed.

At 3:01 on a Friday, I got a call from Principal Ross.

“Mr. Landry,” she said, steady in the way women are steady when they’ve used up all their allowed panic. “I wanted to let you know—we’re having an assembly next Thursday for the kids who helped in the emergency last week. The fire alarm malfunctioned. Bradley ushered the sixth graders out calmly. He deserves a certificate.”

“Thank you,” I said. We do not hang certificates where the drawer can see them. We hang them where boys can.

She hesitated. “Also… Kyle’s coming back tomorrow. He said—he said he wanted to do it correctly this time. He asked if he could apologize to the student he hurt. The counselor will be there. Tommy’s parents agreed.”

“Good,” I said. I kept my voice neutral so I did not make her job harder hours later when she would have to be the one to stand in a hallway if voices rose.

At 3:42, my burner rang. Unknown. But the shape of the silence—how it stretches before a man speaks—told me all I needed.

“You cost me friends,” the voice said. Smooth. Expensive. “Very rich friends. You cost me six very good Tuesday mornings.”

“I cost you crimes,” I said. “That’s different.”

“People in my network used to tell stories about an accountant,” he went on. “We laughed. Numbers don’t kill people, we said. Turns out, some do. Are you proud?”

“No,” I said. “But I am not ashamed.”

“You took Spence’s toy,” he said, tone slipping, arrogance cracking along old fault lines that have names like father and country and greed. “You think you can take ours.”

“I don’t think,” I said. “I count.”

“Your boy,” he said then, too casually. Men drop their cards when they think they are gods. “He goes to school with police officers and principals who think cameras are shields.”

Everything narrowed—the hallway, the air, my fists. I made my voice not move.

“What do you want,” I said.

“A pause,” he said. “And respect.”

“I don’t respect men who hurt children,” I said.

“You will,” he said. “Or you will learn how to count funerals.”

I could hear traffic in the background of wherever he was—a city that does not forgive, horns that improvise. I pictured his shoes. I pictured his tie. I pictured my son, twelve and brave, standing up in a cafeteria because he thought that’s what the world owed itself.

I took a breath as if I’d just put my head above a lake and said the only word I was sure would put this man in his proper place.

“Accountant.”

No flourish. No volume. A simple entry in a ledger.

He didn’t hang up. The silence went stiff and then liquid. The sound shifted—a hand over the receiver, a whispered sentence to some other man in a room who knew the story. He came back, voice trying to slow its own heart rate and failing.

“You forgot who you were for a long time,” he said, but it didn’t land. It sounded like a wish.

“I remembered who I work for,” I said.

He cut the call. Ran, I imagine. Men like that always do when they find out math isn’t on their side.

I stepped into the living room where Bradley was sprawled on the rug with his wind turbine and the dog from next door that is not ours and knows it. Meline looked up from a book she had finally started because the house was quiet enough to allow an entire paragraph.

“All right?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Now.”

The next morning at Riverside, a boy with a cast met a boy he had hurt. He sat on a chair too big for both of them and said the first apology as if he had rehearsed it all night in a mirror and needed to swallow his pride with each syllable. A mother held a breath and let it out. A principal let her shoulders drop a quarter inch. A father stood in the hallway with his hands in his pockets and did not reach for anything sharp.

After, Bradley came out and found me by the trophy case with its fake marble and its plaques that say people’s names under the word sportsmanship.

“He meant it,” Bradley said.

“I know.”

“Are you still… doing the other thing?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Until the ledger balances.”

He nodded, practical. “Do you need more straws?”

“I always do,” I said.

On Sunday, the wind was good and the grill was lazy. Jules brought pie that decided it wanted to be soup. Meline handed me a beer like a kind of truce with the week. The roses—ridiculous, gaudy, exactly as fragile as anything beautiful—breathed in the evening air.

“Do you think,” she asked, “we get to keep this?”

“No,” I said truthfully. “We get to choose it. That’s better.”

“Will they keep calling you that?” she asked then, not because she needs reassurance; because she hates falsehood dressed as comfort.

“Probably,” I said. “Sometimes I’ll say it first.”

“Will it keep making bad men run?” she asked.

“Not always,” I said. “Sometimes it will make them stop long enough for good men to catch up.”

She nodded. “Then say it.”

Bradley’s windmill spun in the yard with an absurd ambition. The dog tried to bite the air. Somewhere downtown, Ray sent me a text with a photo of an empty warehouse and the word closed.

I have learned that some stories do not give you tidy endings. They give you work. They give you rooms to walk into and rooms to leave, and a drawer you keep half-open because you have finally admitted you are two men and both are honest.

But some endings you get to write on purpose.

The next time a voice tried to reach into my house with a threat, I met it at the threshold with a single word and watched it trip on its own feet.

Because here is what I know now, and it’s as simple as any arithmetic problem Bradley will get for homework: you put mercy on one side of the equal sign and vengeance on the other and you carry what you must. You never round down on children.

And if a man shows up at your son’s school with a suit and a sneer and thinks he can do business in a room with a whiteboard and a principal’s plant and a twelve-year-old’s defiance, you look him in the eye, you remember the rooms you survived, and you say one word that has always meant the same thing in the only ledger that matters.

Accountant.

He’ll remember to be afraid. And if he forgets, you’ll remind him.

The End.

News

Cheating Wife Walked Into The Kitchen & Froze When She Saw Me,”You Didn’t Leave?”… CH2

Part I The saw kicked back and bit deep into my palm, splitting skin like wet paper. A scarlet V…

My Parents Hid My Tumor, Calling It “Drama”—Then the Surgeon’s Discovery Stunned Everyone… CH2

Part I The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I…

My Dad Left Me On The Emergency Table Because My Sister Had A Meltdown – I’ll Never Forget This… CH2

Part I Antiseptic burns in a way that feels righteous. It bites the skin as if scolding flesh for failing…

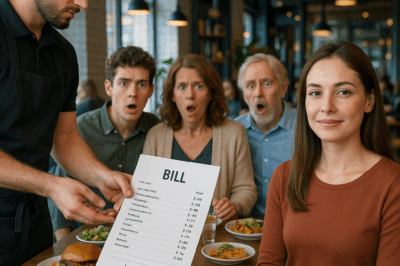

‘RACHEL, THIS TABLE IS FOR FAMILY. GO FIND A SPOT OUTSIDE.’ MY COUSIN LAUGHED. THEN THE WAITER DROPP… CH2

Part I The leather folder landed in front of me like a trap snapping shut. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t…

I spent 3 nights watching over my mother in the hospital. I came home one day early. No one was… CH2

Part I My mother always said hospitals breathe like sleeping whales—vast, humming, heavy with the weight of lives passing over…

I FOUND OUT THAT MY NEIGHBOR HAD ENTERED MY HOUSE SEVERAL TIMES WHILE I WAS AT WORK, SO I DECIDED… CH2

Part I The coffee mug that changed my life wasn’t expensive. It wasn’t even particularly pretty—not if you asked me….

End of content

No more pages to load