Part I

Two days. That’s all the notice I got.

A stiff white envelope sat on my doormat in Atlanta, heavy with that courthouse smell—old paper and duty. No text, no call, just embossed lettering that said I was expected in Charleston for the reading of my mother’s will. The name printed in perfect black ink: Miss Odellin Marin. It read like a place card at a table where I’d never been welcome.

Kalista had promised to “keep me posted.” That was at the funeral two weeks ago—a funeral she choreographed down to the lilies and the alumni press release. I’d been slotted into a two-minute private viewing with Mom between the florist and the photo slideshow. Then nothing. Until now.

I sat on the couch without opening the letter and reached for the silk scarf I kept folded in my side table. Cream, soft, with faded blue stitching in one corner—JM. Jacqueline Marin. Mom’s initials. The last thing she pressed into my hand before her hands started shaking too much to hold anything. I held it the way you hold a bruise, gentle without knowing why, then returned it to the drawer and went to pack. If my sister wanted a performance, she was about to get one—just not the kind she’d rehearsed.

Charleston smelled like magnolia and salt the way it always did when I was a kid riding in the backseat with the windows cracked, pretending the live oaks were reaching down to pat my head. The gate to the estate creaked open slow, like even the house disapproved of me showing up uninvited. I parked around back because that’s what I’d always done. Front drive was for guests and Kalista. House rules.

The housekeeper answered my knock with her eyes on the floor. “Oh. You came,” she said, as if my attendance were optional, a curiosity.

“I was invited,” I said, holding up the envelope before she could pretend she hadn’t seen it.

Inside smelled like lemon polish and lavender soap. It always did. Mom liked things clean enough to squeak. The assistant—Kalista’s new one, tall and pouty with a headband that said prep school more than work—appeared from the butler’s pantry, blinking like sunshine offended her.

“I didn’t know you were attending,” she said, like a doorman at a private club.

I pointed to the letter again. She sniffed. “They’re on the terrace. Garden attire.”

Of course they were.

Under a striped canopy, the family looked like a country-club ad spilled across a long table. Aunt Dolores stood when she saw me, her smile a little too bright, her hug a little too shaky. “Odell, sweetheart. I’m so glad you’re here. Your mom would be, too.”

“I hope so,” I said. The rest of them pretended their coffee needed stirring.

Kalista turned at the sound of my voice like a radar finding a blip. She smiled with all her teeth. “Well, look who showed up,” she sang, hand fluttering to her pearls. “Didn’t know they were letting plus ones to the reading.”

A few tight laughs. Mostly silence.

I didn’t answer. I’d learned years ago that my sister was powered by reaction. Don’t feed it. I took a seat at the far end, the place you give to someone who’s technically family but shouldn’t ruin the pictures. The hydrangeas along the stone wall were blue and defiant, blooming like they’d decided to outlast us all. I breathed and let the color steady me.

This house held a lot of versions of me: the girl who came home from a double shift and slept on the couch because her bedroom had turned into “seasonal storage” without anyone asking; the niece who cleared plates while the “real adults” talked; the daughter who was always supposed to be grateful. Today, I was the woman with a backbone and a folder.

Through the French doors, the lawyer—Mr. Whitlow, the kind of man who wore his summer suit like it was a uniform—stepped into the sunroom and cleared his throat. Conversations died. Spoons stopped clinking against porcelain like the sound offended the moment.

Kalista rose with him, placing a hand on his arm like they’d co-hosted charity balls. “Let’s just hope this isn’t one of Odell’s surprises,” she said, bright and cutting.

The room held its breath. I kept my mouth shut.

Whitlow blinked, regrouped. “Thank you all for coming,” he said, voice pitched to polite. “We’ll do our best to be brief and respectful.” He opened his leather briefcase with a care that looked like stalling and pulled out a single sheet. “First, we confirm attendance. Miss Marin—” he didn’t look at which Miss Marin “—if you don’t mind, please sign this.”

I took the page. Blue header, Whitlow & Pierce embossed, a block of legalese, a signature line. Acknowledgment of Attendance and Understanding of Probate Proceedings. No details filled in. Just a blank line with my name typed above it.

“Just me?” I asked.

“Formality,” he said.

Aunt Dolores murmured, mostly to herself, “They didn’t ask me last time.”

“I’ll need a copy,” I said, handing it back. Whitlow nodded and slid it back into his briefcase without producing a copy. Noted.

From the corner of my eye, I caught movement. Kalista’s hand dipped into her designer purse, extracted a folded sheet, slid it under the table toward Uncle Rowan. It was quick, practiced—the kind of motion you make when you’ve rehearsed it. He palmed it expertly.

Set-ups look subtle when you’re used to seeing them. My spoon stayed on its saucer.

“If we’re settled,” Whitlow said, adjusting his glasses, “I’ll begin reading the Last Will and Testament of Jacqueline Wright Marin.”

When he said Mom’s full name, something in me loosened and tightened at the same time. He glanced at me. “You may want to sit,” he said, then realized I already was and cleared his throat again.

“Per the last legally witnessed and notarized testament,” he read, voice going slightly formal, “the entirety of the Marin estate—comprising the property, monetary assets, personal belongings, and residual income—is hereby left to Odellin Marin.”

Somewhere behind me, a glass shattered. Someone hissed, “You’ve got to be kidding.”

At the far end, Kalista’s hand jerked and sent her water glass skittering. Her practiced expression cracked. “What?”

Whitlow didn’t blink. “That is what the document states.”

I didn’t look at anyone. My eyes locked on the hydrangeas. My name. Everything. It didn’t feel real. It felt like a story someone else had told, and I’d stumbled into the end.

“However,” Whitlow continued, and there it was, the word that pulls the rug, “there is a clause. The inheritance is contingent on Miss Marin maintaining the family estate, residing in it, and keeping it functional for a minimum of one year. During this time, no sale, redevelopment, or transfer of property rights is permitted. In addition, Miss Kalista Marin is barred from initiating or facilitating any structural changes, financial reassessments, or sale discussions concerning the estate during this period.”

A low wave of whispering. My stomach did a slow flip. This house had never been a home to me. It was a stage where I’d been asked to pass hors d’oeuvres. Now it was a condition.

“This is a joke,” Kalista snapped, pushing back her chair so hard it squealed. “That is not what Mom wanted.” She pivoted to me, voice sharpening. “You put that in her head, didn’t you? All those calls at the end. Crying on cue. Playing martyr while I handled everything.”

“Kalista,” Aunt Dolores warned softly.

“No. They all need to hear it.” She turned, performing for the handful of cousins and family friends near the back. “She moved away for years, then popped back in when Mom got sick like Florence Nightingale rewriting history. She didn’t even cry at the funeral.”

I pressed the scarf in my bag between my fingers until the thread bit my skin. If I cried now, Kalista would have proof to mount on a wall.

“Miss Marin,” Whitlow cut in, the lawyer tone back. “These terms were written by your mother in her hand. Signed in front of a notary and two independent witnesses.”

“She was confused,” Kalista said, the word loud enough to bruise. “You said so yourself, Dolores.”

“I said she was tired,” Aunt Dolores said. “Not confused.”

Silence. The kind where you can hear the clock decide not to chime.

“Did she leave anything else?” I asked, my voice staying calm only because it didn’t feel like it belonged to me.

Whitlow removed a pale blue envelope from a side pocket. “She did. A letter for you.”

He placed it in my hands. It was heavier than it should have been. I broke the seal. To my youngest was written across the top in Mom’s familiar loops. I didn’t plan to read it aloud. But the room had arranged itself like a witness and the words asked to be heard.

“To Odell,” I read, the first syllables catching, “you showed up when no one else did. You made me soup when I couldn’t speak. You stayed when your sister filed the power of attorney papers without telling me. You are the only one who didn’t ask me to sell the home—only to rest in it.”

The sunroom held itself very still.

“I was not confused when I wrote this. I was tired, but not confused,” I continued. “And I changed the will after she tried to sell the house beneath my feet. I won’t be tucked away while strangers walk our halls. Don’t let them take everything.”

I looked up. There’s a temperature a room reaches when a story shifts—a flicker of eyes, a chin jerking half an inch, the way a cousin suddenly finds the carpet deeply interesting.

Kalista recovered like an athlete. “She didn’t do anything she didn’t want,” she said, too loud. “She was delirious. Do you really think she could make decisions like that from a hospice bed?”

“Can you confirm the date?” I asked Whitlow, turning the letter toward him.

He leaned in. “This is dated a month after the prior will change. Witnessed by two of our staff. The hospice nurse’s chart notes show full cognitive clarity that day.”

Color drained from my sister’s face. For a moment, she was the kid who had gotten caught, not the woman who had built a life on never getting caught.

“You pushed her,” I said quietly—not as accusation, but as fact. “You called a realtor while she was recovering from pneumonia.”

“You have no idea what she was like,” Kalista snapped, pitch slipping. “She clung to your voice because you told her what she wanted to hear.”

“Don’t,” Aunt Dolores said, and it landed like a hand on a hot stove. “I saw her with my own eyes. Your mother was more herself in those days than she’d been in years. And you? You tried to evict her from her life.”

Kalista reached for her glass with a hand that wasn’t steady. No one moved to fill the silence for her. Even Brent—her perpetual yes—studied the tablecloth like it might save him.

I walked to the front window and looked out at the live oaks. The letter felt like a pressed flower in my hand, a thing transformed to outlast the season. “She didn’t want to be sold like a property,” I said, not to anyone in particular. “I honored that.”

The hush that followed wasn’t the old family hush—the one that meant I should shrink, apologize, disappear. This one had edge. Fear. Realization settling in like a storm that wasn’t going to miss us after all.

We migrated to the club’s garden lounge because grief, money, and finger sandwiches share the same calendar in families like mine. Silver trays sweated. Jazz hummed like it could soften hardwood. I sat by the window with a cup of black coffee that tasted like focus. The letter was still in my lap, warm now, familiar.

Across the room, Kalista worked the crowd. She leaned in close. Touched forearms. Nodded with her I-care face. Damage control was her native language. Words drifted over the clink of ice.

“Odell always had this unique relationship with Mom,” she said to a trio of Mom’s church friends. “She could make herself the victim. I just wish she hadn’t taken advantage when Mom was at her weakest.”

One of the women—who used to braid my hair before church and scold us for running—let out a breath made of disappointment. “That’s low,” she said. Not quiet enough.

Aunt Dolores stood, gathered her purse with that economy of motion women learn, and walked out the French doors. No speech. No scene. Just a line drawn.

I set down my cup and stood. I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t have to. “Kalista,” I said, and the room pivoted. “I never manipulated anyone. And I have the documents to prove it.”

She blinked. “Excuse me?”

“I kept the paperwork,” I said. “Emails. Signed documents. Timestamps. The voicemail Mom left after you filed the power of attorney behind her back.” I felt the room lean in. “If you want to go public with that story, I’ll go public with the truth. All of it.”

A cough in the corner. Chairs angled a degree in my direction. For the first time in our lives, my sister did not look like the center of the circle. She looked like someone had moved the chalk.

“You wouldn’t,” she said.

“You’ve mistaken quiet for weak your entire life,” I said. “That’s not on me.”

I sat. The room did the rest. That night, a manila envelope slid into my mailbox like a dare. Petition to Contest Probate on the header. Undue Influence circled like a threat. It wasn’t just about money anymore. It was about erasing me. Again.

I went to my home office, turned the lock, and pulled open the bottom drawer of the file cabinet Mom and I refinished one summer when I was nineteen and broke. The red folder sat where I’d left it. Supplement Addendum 3 in Mom’s careful hand. Notarized. Dated. Witnessed.

Bank statements. Realtor emails. The hospice nurse’s logged report. And a note to me typed late at night, the time stamp glowing: Don’t delete these in case I forget later. You’ll know. —M.

I knew.

And this time, I wasn’t coming to the courthouse to play quietly at the kids’ table. I was bringing the table.

Part II

The sun hadn’t bothered to climb all the way up when I left the house, but the air already had that Charleston heaviness, like it knew a storm was coming and wanted credit. I parked a block away from the courthouse—habit, defiance, self-preservation—and walked the rest with the red folder tucked flat in my tote like a spine.

I heard the crowd before I saw it: the click of tripods, the hum of battery packs, the artificial clearings of throats that mean cameras are rolling. A ring of press had bloomed on the steps, microphones sprouting up from fists like impatient flowers. And in the middle of it, where she always finds herself, was my sister.

Kalista wore lavender, because of course she did—the compassion color. Her hair was immaculate; her voice warbled at the top in the places that read as tenderness. “I only ever tried to protect our mother,” she told a reporter with artfully rimmed eyes. “But money—” here she paused, let her mouth tremble “—money can change people.”

The reporter nodded like a metronome, pen skating. “We understand your sister is due to arrive shortly.”

A flash of tightness in Kalista’s jaw. “Yes. I’m sure she has…her version.”

I stopped just behind the camera line and watched the performance, counting beats. Mom used to say you can tell if someone’s singing by how they breathe between notes. Kalista had perfected grief-breath. She’d practiced.

The lead journalist—a woman in her forties with a coffee stain on her sleeve and eyes that read rooms and didn’t forgive them—caught sight of me over her cameraman’s shoulder. She pivoted. “Miss Marin,” she called, voice steady. “Would you like to respond to your sister’s statement?”

I stepped forward until the microphones formed a neat little semi-circle and the sound techs adjusted levels like they were about to record a single. I didn’t answer the question. Instead, I reached into my tote and took out a sealed envelope. Clear sleeves inside, tabbed and labeled. Mom taught me to keep things neat enough to survive scrutiny.

“Please review this,” I said, handing it to the coffee-stained reporter. “Timestamped screenshots. Email threads of wire transfers from our mother’s joint account. And a notarized letter from her hospice nurse dated two months before she passed.”

She slid the packet out and flipped the first page, lips moving as she read. Her eyes met mine after three sheets. “Ma’am,” she asked, the formality automatic, “where did you get this?”

“My mother gave it to me,” I said. “She knew this day might come.”

Before the reporter could frame another question, a voice from the edge of the crowd cut through: “I can confirm that.”

Heads turned. A woman in scrubs—faded, clean, with an old badge that swung when she walked—stepped forward. “Janette Holloway,” she said, touching the badge. “Night-shift hospice. I filed a report when Miss Kalista raised her voice and waved a checkbook at our patient. Jackie cried herself to sleep. I logged it. It’s on file.”

A murmur rolled over the steps like wind. The cameramen instinctively widened their circle.

“This is slander,” Kalista snapped, a hand shooting toward the mics and stopping an inch short. She’d been coached. “None of this proves manipulation. Our mother was dying. She didn’t know what she was saying at the end.”

I turned to her and did the thing she hates most: I spoke plainly. “She knew exactly what she was saying. She changed her will after you called a realtor behind her back and walked him through the house while she was asleep. You withdrew over eight thousand dollars without permission. You filed power of attorney while she was recovering from pneumonia.”

Gasps are dramatized in movies. In real life, it’s subtler—a shift in posture, a throat clearing that doesn’t complete. Someone at the back muttered, “Lord have mercy,” and actually meant it.

“I’m not here to ruin you,” I said, quiet enough to make them lean in. “I’m done pretending.”

Silence fell in a way I recognized: the room (or steps, or family) deciding which story to believe. This time, I didn’t wait to see. I walked up the remaining stairs past the microphones and badge lanyards and into the courthouse’s cooler air. It smelled like paper and patience.

The probate courtroom was smaller than television makes them, uglier, too: beige walls, brown wood, the kind of carpet designed to hide stains. But it held people like a net: neighbors with opinions, cousins who’d never say them in public, two of Mom’s church friends clutching programs from a service long over, and the press, anchoring the back like a second jury.

Kalista stood near the plaintiff’s table in a brighter blazer than decorum asked for, one hand on a folder whose contents I could have guessed asleep. I took my seat beside Aunt Dolores as if we came together; she squeezed my fingers twice—once for courage, once for confirmation.

“All rise,” the bailiff intoned, and we did, a ragged unison.

The judge was the kind of man who looks like a grandfather until you put a robe on him and a bench under him. “We’re here to finalize the probate of the estate of Jacqueline Marin,” he said, tapping a file. “We’ll hear both parties’ evidence.”

“Miss Kalista Marin,” he nodded to my sister, who stepped into the center of the room like she owned the light. “You may begin.”

She cleared her throat, a gentle cough that would be a sob before the afternoon was over if she needed it. “Your honor,” she began, voice pitched two degrees higher, sincerity keyed in, “this is my mother’s legally recognized will: signed, witnessed, notarized.” She placed a document on the clerk’s table like she was offering bread at communion. “It names me sole executor and heir. I accepted that responsibility not out of greed but duty. My sister”—that word cupped like a bruise—“was not involved in our mother’s care during the last year. She appeared only once the paperwork was done. I’m afraid…there may have been undue influence…after that.”

The word undue hovered in the air like smoke.

“Miss Odellin Marin,” the judge said, turning to me. “Do you wish to respond?”

I didn’t look at the reporters. I didn’t look at Kalista. I carried the pale blue envelope to the clerk with both hands as if it were a fragile thing and not a bomb. “Yes, your honor. I have a later will. Signed by my mother. Dated and notarized one month after the version presented by my sister.”

The room contracted. The judge slit the flap with a practiced motion, slid the document free, and read. His mouth did a subtle thing I’d been waiting to see: the not-quite smile of a man who expected a twist and got the original flavor.

“This appears legally valid,” he said. “Date: July ninth. Four weeks after the previous will. Witnessed by Dolores Marin and Janette Holloway. Notarized by Erica Platt. State-certified.”

Kalista moved forward a step like she was being pulled by a string. “She forged it,” she said. “It’s fake.”

“Your honor,” I said, turning to the AV tech at the side of the room, “could you play File A?”

The tech nodded at the judge. He allowed it. The wall screen blinked to life and there she was: my mother, thinner than I like to remember, in a pale robe with a pattern I recognized because I’d folded it the last time she wore it. Her hair was brushed; her eyes were clear in a way that still breaks me.

“If this is ever played,” she said, looking straight into somewhere beyond the lens, “it means Kalista has tried again to twist my intentions.” She paused to sip water; I heard the faint beep of her oximeter. “I made another will because she tried to put me in assisted care against my wishes. She contacted a realtor behind my back and withdrew over eight thousand dollars from our joint account without my permission. Odell didn’t pressure me. She protected me. This is what I want. Clearly, freely, with full capacity.”

The only sound in the room was the squeak of someone’s shoe when they crossed their leg.

The judge turned to Kalista. “This confirms testamentary intent,” he said evenly. “Unless you can provide irrefutable evidence of fraud, which—given this footage and the notary’s log—I do not see, this July ninth will controls.”

“She was dying,” Kalista said, and for the first time the veneer sanded down and the metal showed. “She didn’t know what she was saying.”

No one met her eyes. Not even the reporters.

“Do you have anything further?” the judge asked me.

“Only this,” I said, and my voice didn’t shake though my knees could have. “I loved my mother. I respected her choices.”

From the first row, Aunt Dolores gave me that small, sure nod again—the kind women in families pass down across meals and crises: you did right.

“Then the court recognizes the July ninth will as operative,” the judge concluded, tapping his file. “Conditions as written shall be enforced. Petition to contest is denied.”

A gavel doesn’t sound like thunder up close. It sounds like a sharp end to a sentence.

I didn’t turn to watch my sister’s face when it fell. I didn’t need to.

By the time we stepped back into the heat, the sun had shifted west, casting a soft gold down the courthouse steps that made everything look gentler than it was. The microphones sprang back up; names were called: “Odell, will you comment?” “Did you expect the video to play in court?” “How long have you had the second will?”

I gave them Mom’s weather face—the one she wore during storms, funerals, Sunday dinners when the table took more than it gave. I put one hand on the railing like it might be a friend and walked.

Halfway down, Romy’s old Toyota idled by the curb, AC leaking out the window like mercy. She hopped out and opened the passenger door with a look that asked the only question that mattered.

“You ready?” she said.

“No,” I answered, honest like a prayer. “But I’m done.”

We drove in quiet—the good kind—with the city sliding past in scenes I’d known since I was a kid: the bakery with the cinnamon rolls like fistfuls of sugar, the woman who sells hand-tied bouquets out of milk crates on Tuesdays, the alley where I’d once hidden to cry and vowed never to again.

At my driveway, dusk settled like a shawl. The jasmine Mom planted years ago breathed out sweetness like it had been waiting for this exact hour to be itself. On the porch swing, I sat and let the cicadas tune up, the house exhale, the edges of the day soften.

Romy hovered in the doorway, then stepped onto the porch and reached into her bag. “Found this in the lining of your mom’s old wallet,” she said, producing an envelope singed at one edge like it had met a match and decided to outlive it. “Didn’t seem like something a clerk should catalog before you did.”

It was addressed simply: To my youngest, my silent warrior. The script was that early-June blue, decisive and tender.

I didn’t open it right away. I set it on my lap and listened to the chimes whisper at the edge of the porch roof and thought about all the versions of silence I’d carried—shame, complicity, protection—and how this one felt different. This one felt like a room I’d built myself.

Then I broke the seal.

You always were the strongest, the first line said, even when they pretended not to see. You didn’t need their praise to matter. Some truths aren’t spoken. They’re lived. And you lived it right. I love you always. Mom.

It wasn’t grand. It wasn’t poetic. But it undid something in me that had been knotted since the day the first gate closed behind me and I chose the back entrance because that’s where I’d been told to go.

Romy came back with two glasses of tea. We didn’t toast. We didn’t speak. We just sat on that swing while the sun slipped behind the trees and the porch light clicked on like it knew when we’d need it, and I looked at the chipped banister and the small-town flower pot Kalista said embarrassed her and the wind chimes that say more than most people do.

The city, the house, my name—none of it felt like a performance anymore. It felt like mine.

Part III

The first night in the house sounded like it was remembering how to breathe without her.

Every floorboard had a story; every window had its own way of resisting the lock before giving in with a soft click. I walked it the way you walk a city you’re not sure wants you, palms grazing the banister, the backs of chairs, the edge of the piano Mom never quite learned. I opened the kitchen window and let the jasmine come in, because that’s what you do when you want a place and it’s not sure it wants you back.

The one-year clause wasn’t a line on paper anymore. It was a mile marker I could see from every room. Reside. Maintain. Keep functional. Whitlow had slid a manila packet across his desk that afternoon—Letters Testamentary and a checklist thick enough to bruise. “You’re the personal representative now,” he’d said. “Keys, accounts, insurance, taxes, vendors, staff. Take inventory. Secure valuables. Document everything.”

He didn’t say grieve because the law doesn’t have a form for that.

I started anyway. A notebook on the kitchen table. Columns. Dates. Rooms. What worked and what didn’t. The hydrangeas got their own page.

On day two, the gas shut off.

I was in the upstairs bath scrubbing the rust ring out of a guest tub with my sleeves rolled when the water turned cold and the house let out a sigh that meant someone turned the valve. The pilot light on the water heater blinked out in the basement like a winking eye. The utility company on the phone sounded apologetic but not enough: “We received a closure request signed by…Miss K. Marin?”

“Rescind it,” I said, steady so the shakes wouldn’t take my voice. “I have Letters. I have a court order. Email? Fax? Pony express?”

They reinstated it after an hour on hold and three forwarded PDFs. I sat on the basement steps between boxes labeled WINTER and CHRISTMAS and watched the little blue flame take again. Somewhere in the ground above me, the hydrangeas were drinking.

They weren’t the only things that needed watering. Staff had scattered with the funeral canapés—housekeeper, gone; gardener, “on hold until the estate was clarified,” as if it hadn’t just been. The cook had left me a recipe card for Mom’s favorite chicken and rice, handwritten in a slanted block that looked like comfort. I put it under a magnet shaped like a crab and defrosted a Trader Joe’s bag anyway.

The second week the HOA left a warning on the door about “inoperable vehicles” because my father had never registered the old Chevy in the carriage house and its tires were sighing into themselves. I sent them a copy of the Letters with a note that said, We’re grieving. I’ll tow it Tuesday. The assistant—Kalista’s—texted from an unknown number with a link to a landscaping company and a perfumed line about appearances.

On the third week, the county inspector knocked with two men in polos and a clipboard. “We received an anonymous complaint about structural safety,” he said. “Rot in the porch beams.”

We circled the porch. His pencil poked the underside of beams that had held families up for a hundred years. There was no rot. There was dust. There was a nail that would need hammering and a soffit that wanted paint. He signed his form and tucked it away. “Anonymous calls get attention,” he said, not unkind. “But facts get filed.”

I made coffee in the good china because I could. I drank it on the back steps in my father’s old hoodie while the hydrangeas bowed and unbowed in the weight of late morning. Aunt Dolores sent over a loaf of bread and a man named Tommy with forearms like rope to haul the Chevy. “Call me before you call a stranger,” she said. “Half this city owes your mother a favor. The other half needs to pay one off.”

The assistant tried again with charm that smelled like hand sanitizer. Wouldn’t it be easier if she took “temporary oversight” of the accounts while I “focused on self-care”? I replied with a copy of the injunction and a smile she couldn’t see. Her “Oh!” came back with a sparkle emoji. I blocked her.

At night, the house shifted in ways that sounded like children running, even though we were never those. I slept on the sofa the first three nights because it felt like a place you could leave too quickly if you had to. On the fourth night I slept in Mom’s room because not sleeping there felt like a betrayal and sleeping there felt like a trespass. I lay on top of the duvet with the windows open and the ceiling fan talking to itself and it didn’t feel like anything but a house where a woman had loved and been loved poorly and then, at the end, just loved. I slept.

That’s when the dreams started—the same looping scene of the sunroom, the letter, the judge’s voice. But there was always a new piece: the way Uncle Rowan’s hand had slid under the table to palm the folded paper from Kalista. The way the housekeeper’s eyes had refused mine on day one. The everything of what we don’t say.

I went looking for proof. Not to punish. To protect.

I started with the obvious: drawers. Desk. Filing cabinets in the library that had more receipts for charity luncheons than taxes. I moved to the not obvious: beneath the lining of Mom’s jewelry box, inside the hollow of a fake book on the shelf titled Charleston Gardens, under the wool of the living room rug where a floorboard popped up just enough to invite curiosity.

On Sunday, I unfolded Mom’s scarf—the cream one with JM stitched in faded thread—and my finger snagged on a rough place I hadn’t noticed. The hem had been unpicked and re-stitched in a way my mother would have had the decency to call “homely.” Inside, flat against the fabric, taped with the kind of tape that was yellow because it had been waiting, sat a key. Bank box size. Tag: Harbor & First. A safety deposit number. My name written in ballpoint on a torn corner of an envelope: for O.

Harbor & First smelled like teller windows and a time before online bill pay. The manager—a man in his sixties with a tie clip that had seen more depositions than he cared to think about—escorted me back after Whitlow faxed over a copy of my Letters. “Your mother was thorough,” he said, unlocking the box that held hers with a practiced dip of wrist and shoulder. “You remind me.”

Inside: the ring I thought had been lost in ‘09. A photograph of my grandparents on the steps in ‘62, everyone thinner and the house too. Birth certificates. The deed in a folder already labeled TOO OLD TO RE-RECORD in Mom’s writing. And a stack of envelopes, banded together with a rubber band that snapped because that’s what old rubber bands do. The top envelope was addressed in my mother’s hand to The Probate Judge, underlined twice. Beneath it: If Kalista Contests.

I sat on the tiny stool bolted to the floor and read with the kind of attention you only pay to the last thing someone left you to understand them by. Mom’s voice speaking as quietly as a letter can.

She’d cataloged everything in the way a nurse charts: dates, doses, symptoms. February 2: K tries to move me to Wilton Assisted. Says “for your own good.” No. March 19: realtor cards in kitchen after pneumonia. March 22: withdrew $8,250. My handwriting below: screenshots attached. And they were—printed emails, bank statements with circles in red pen that bled through to the other side, a note from the hospice social worker about “patient expresses concerns that daughter is accessing accounts without consent.”

At the bottom: another video on a thumb drive taped to a page, labeled in her careful scrawl: If they call me confused.

I texted Whitlow one sentence: Found a box. Bringing it. He texted back a courthouse time and the scale emoji, which is how lawyers say good.

On the way home, I stopped at the grocery store to buy milk and a box of cake mix because I wanted the house to know ordinary would live there again. A woman in the produce section touched my arm with the caution you use with animals and grief. “Your mama was a piece of work,” she said, voice low, affectionate. “But she called me every March on the third to remind me to renew my tag because she knew I’d forget. You let me know when you have people over. I’ll bring deviled eggs.”

Her name was Luanne. She lived three doors down. I put her number in my phone under Deviled Eggs and when I looked at it later, it made me cry for the first time in days.

Kalista didn’t cede ground. She switched tactics. Anonymous calls turned into official letters. The foundation Mom had sat on for twenty years—the one that funded school libraries and sometimes, secret scholarships—sent me a scheduling request for an emergency board meeting. Agenda: interim leadership. The chair? The bank. Co-chair? My sister. She’d brought her lavender to a conference room with beige carpet and a long table and wanted to add “Executive Director” to her collection.

“You can’t do that,” I said, to the board, to the room, to the portrait of the donor on the wall who always looked bored.

“Why not?” a man named Cal asked, waving a printed mission statement. “Continuity.”

“Because,” I said, placing a photocopy of a paragraph from the original bylaws in the center of the table like a playing card you’ve been waiting to lay down, “Article VI, Section 3. Any officer who attempts to profit personally from any foundation asset shall be barred from office.”

The room blinked. The chair—who’d been neutral until the last check cleared—leaned forward. “Are you alleging—”

“I’m presenting,” I said, and slid a packet across: Mom’s notes, bank statements from the Harbor & First box, a single page highlighting a transfer from the foundation’s discretionary fund to a limited-liability company that looked suspiciously like Kalista & Partners Event Design with an address that looked exactly like my sister’s front door.

Kalista’s face did the fractional freeze I recognized from childhood when a teacher asked if she’d copied a paper and she hadn’t prepped the lie that day. “It was a reimbursement,” she said. “For a gala.”

“The bylaws require pre-approval,” the chair said gently, the way you tell a child not to touch the stove. “We’ll table this.”

She stood too quickly and the lavender bled into magenta with heat. This time when she left the room, no one followed.

Two months in, a leak appeared in the library ceiling. “Because of course it did,” Romy said, standing on a ladder while I held a bucket and an opinion. The plaster bubbled like a bad lie. Tommy came with tarps and a smile and discovered a hose that had been “nudged” off the roof spout. “Wind didn’t do this,” he said, mouth thin.

We checked the camera I’d bought after the gas stunt and mounted under the eave. Grainy, greenish, like footage of arguments ghosts have. But it was enough to show a person—tall, ponytail, headband—climb the trellis and fumble at the downspout. Kalista’s assistant didn’t smile for the first time since I’d met her. The police called it trespassing. The DA called it “a civil matter likely.” Whitlow called it “admissible.”

We called a roofer and baked the cake mix that had been waiting in the pantry. We ate it on paper plates in the library while the dehumidifier hummed and the word functional felt like a joke we were telling back to the clause.

By autumn, the house had taken me like a cat takes its person: on its terms, one room at a time. I painted the back bedroom the pale blue Mom had liked and hung nothing on the walls because empty space was its own honor. I hosted a book night for the neighborhood on Wednesdays. Luanne brought deviled eggs with paprika sprinkled like punctuation. Nurse Janette came and sat in the corner and read aloud like we were all in one room at the end again where people did simple things and survived them.

The judge’s clerk called on a Tuesday. “There’s been a file submitted under seal,” she said. “The court requests your presence Friday morning.” She didn’t say what because she couldn’t. She didn’t say who because she didn’t need to.

I walked into Whitlow’s office with a tote and a thermos and Mom’s scarf around my neck. He was already standing, which he didn’t do often. He handed me a copy of a court notice stamped in red: In Camera Review. We would go to chambers, not the courtroom, which meant this wasn’t theater. This was surgery.

“What is it?” I asked.

“When your mother set up the trust that undergirds the estate, she added an addendum twenty years later,” he said. “We knew there was an update. We didn’t know…this.”

He slid a page across the desk. Mom’s handwriting again, neat enough to pass, furious enough to feel.

If at any time my firstborn child engages in actions to remove me from my home, or to profit personally from the foundation I endowed, she shall be barred from serving as officer or beneficiary of any associated trust for a period of ten years.

There were dates. There were signatures. There were two witnesses: Dolores and a name I knew and didn’t, then saw again: Rowan.

“Your uncle witnessed this,” Whitlow said, watching my face. “And tried to hide it with whatever that folded paper was under the table.”

My laugh came out wrong. “Of course he did.”

He placed another paper down, this one with a new signature: Judge Addison. A hearing. Friday. Chambers. All parties.

When we walked into the judge’s chambers on Friday, the room had that hum of machines you can’t see—air vents, power strips, history. Kalista sat at one end of the small table with a lawyer I didn’t know and a complexion that looked powdered too quickly. Aunt Dolores sat behind me because she refused not to see it. Uncle Rowan stood by the bookcase as if proximity to leather spines might absolve him.

The judge closed the door himself. “I called this in camera,” he said, “because what I’m about to say doesn’t need an audience.”

Kalista’s smile stretched. “Your honor, before you—”

He held up a hand. “Miss Marin, you’ll want to listen.”

He slid the paper—the addendum Mom had written, the one Rowan had witnessed—across the table into the light.

Kalista’s hand hovered, then dropped. Her mouth opened and then decided against words. For once, the room didn’t belong to her.

She froze.

Part IV — In Camera (≈1,520 words)

The judge didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to. He laid the page down between us like a scalpel.

“Ms. Wright-Marin drafted this addendum to the trust twenty years after its creation,” he said. “It was witnessed by two individuals and notarized. It states that if her firstborn child attempts to remove her from her home or profit personally from the foundation she endowed, that child is barred from serving as officer or beneficiary of any associated trust for ten years.”

He let that sink in. The room did the heavy lifting—machine hum, clock tick, the faint hiss of conditioned air. Aunt Dolores’s hand found my shoulder and stayed there, a lighthouse.

Kalista’s lawyer recovered first, a man with expensive hair and a voice that had carved many soft noes into yeses. “Your honor, my client disputes the validity of that addendum,” he said, smooth as a prayer. “The timing is suspicious. The witnesses are—”

“Her brother,” the judge said, cutting through. “And her sister-in-law. Whose signatures are on the page. Who will testify to that effect. And whose initialed copies were found in the bank’s safety deposit box under seal.” He slid a second sheet toward the defense table—a copy of the witness page, the ink still living.

Rowan flinched. Kalista didn’t look at him. She stared at the paper like it had betrayed a private promise.

“Miss Marin,” the judge continued, and when he said her name that way it sounded like a choice, “I will not belabor this. Your mother anticipated this exact set of events. She drafted protections. This court will enforce them. Effective immediately, you are barred from serving as officer of any trust associated with the estate or the foundation, and you are barred from receiving distributions from said trusts for a period of ten years.”

Kalista opened her mouth. Closed it. Something in her jaw flickered—the fight between cry and curse. She chose neither. She chose stillness.

The judge turned to Rowan. “As to you,” he said, tone cooling, “you witnessed this addendum and failed to present it when Mr. Whitlow requested all operative documents at the initial reading. That is a serious omission. I will refer this to the bar for review.” He lifted a hand before the man could sputter. “Yes, I know you are not practicing. Your professional ethics do not retire because you prefer golf.”

Rowan’s face bled into the books behind him. A man can be a library and learn nothing.

“As to the foundation,” the judge went on, “this court is not its governing body. But I will note, for the record available to its board, that the addendum’s language is clear. Any attempt by the firstborn to seat herself in office there shall be null.”

He folded his hands. “Miss Odellin Marin,” he said finally, looking at me. “You know what your mother asked of you. Maintain the house for a year. Keep it functional. Live in it. After that, the estate is yours to administer as you see fit within the terms of the trust. Do it. Don’t let these proceedings steal the living out of your life.”

It wasn’t a benediction. But it was more than a ruling.

He stood, which meant we stood, and the bailiff opened the door. Outside, the hallway felt like a different temperature.

Kalista walked past me as if the air would burn her if she slowed. She didn’t look at Rowan. He didn’t look at her. Aunt Dolores let them pass, then leaned toward me and said, with the pleasure of a woman who’s been right and patient, “Your mama could see ten corners ahead.”

“Like chess,” I said.

She smiled a tiny battlefield smile. “Like a nurse.”

We didn’t hold press on the chambers ruling. That wasn’t theater; that was surgery like I said—blood you don’t show. But the board heard. The chair called a special session. Kalista’s lavender did not make it onto the agenda.

I walked into the foundation’s conference room with a tote that had lived more lives in the last month than most luggage. The board members shifted in their chairs with the weight of guilt and habit. The chair cleared his throat. “Thank you for attending on short notice,” he said, staring at a place on the wall where an art donor’s name had been removed and left a ghost rectangle. “We’ve received the court’s notice regarding the trust addendum.”

“Before we go any further,” I said, “I’d like to enter into the record the reimbursements made to Marin & Partners Event Design from the discretionary fund without preapproval.”

Kalista’s lawyer—now a guest, not counsel—raised a hand in a motion too slow to be objection. “We’re not here to—”

“We’re here,” the chair said, sharp enough to surprise himself, “to keep this institution from becoming anyone’s boutique.” He looked at me. “Miss Marin, what do you propose?”

I hadn’t slept well the night before. Decisions felt tall. But Mom’s handwriting in the bank box had been certain in a way that passed like a baton. “An interim slate of officers,” I said. “No family. A forensic audit of the last three years. A codicil to the bylaws requiring two signatures on any discretionary spend over five thousand. And a commitment—public—to the libraries that gave my mother a home when her house didn’t.”

A murmur went around the table, the kind that feels like relief and looks like courage trying on a coat.

“Seconded,” said a voice to my left. Nurse Janette. In a blazer I’d never seen, her badge tucked away like a talisman in her pocket. “Jackie used to say the board was her Thursday night church. Let’s keep it clean.”

The vote wasn’t unanimous. But it was enough. Kalista gathered her folder and left before the coffee cooled.

By Thanksgiving, the house had settled into me and I into it. I learned the sound of rain on the back porch—a rattle that meant the downspout was clear, a thud that meant it wasn’t. The deviled eggs became a standing appointment. The small room at the front of the house—the one we’d always called the sewing room even though no one had sewn in it since ‘94—became a reading room with two squashy chairs and a lamp that made any book look like it might end well.

The first cold night, Romy and I found the box of old quilts. We shook the cedar dust out on the back lawn and laughed when the wind tried to steal them. “Your mother would scold us for airing her life like this,” Romy said, pinning a corner with her knee.

“She’d scold us for everything,” I said, and the sting had gone out of it.

We decided—Aunt Dolores, me, Luanne, Janette—that the house would have a new season. Not just galas. Tuesday soup. Friday porch. The foundation’s audit finished in December with a board announcement that read like closure in a language only money speaks: Controls tightened. Confidence restored. Funds returned. Kalista’s name did not appear. Neither did mine. It was the best sentence in the paper that day.

On New Year’s Day, I carried the box from Harbor & First up to Mom’s room and set it on the bed. I took out the ring and wore it for the first time because I felt like the person who could. I put the photograph from ‘62 on the dresser and told the woman in the picture—my grandmother—that we’d held, thank you. I folded the envelopes back into the bank’s wrapping as if paper gets cold. I slid the scarf into the drawer next to my socks because that’s where things you love should live: with what you use every day.

Kalista texted once. A picture of Mom’s portrait, the oil one with the soft lighting that had hung in the dining room since 2001. When will I be allowed to take this? she wrote. It’s mine.

I typed. Deleted. Typed again. The portrait belongs to the estate. You’re welcome to visit it any Thursday between two and four when we open the house to the public for the new local history series. The message read harsher than I intended. It also read true.

She did not reply.

In February, the judge scheduled a final status conference on the probate to close out the to-do list the law needs. “You’ve complied with the conditions,” he said, flipping papers in the way that shows he reads and remembers. “Residence. Maintenance. Function.”

I brought photographs of the porch repaired, the foundation’s revised bylaws, a spreadsheet of the house’s expenses with all those precarious numbers that used to make my stomach spin starting to look like a plan. The judge glanced at the photographs. “Hydrangeas,” he said, unexpected softness. “My mother had those.”

“They’re stubborn,” I said.

“Good,” he said, and signed the last page with a flourish I liked him for. “Be stubborn. It serves houses and women.”

On the way home I stopped at the florist and bought freesia because Mom had taught me that not everything has to match to belong on a table. I put them in a mason jar at the center of the kitchen and made a batch of the chicken and rice from the recipe card to send to Luanne because she’d had a cold and I wanted to do a thing Mom would have done without being asked.

On the porch that night, I sat with Romy and we watched the neighborhood pass: the boy on the bike with the determined face, the couple who always argued gently about trash day, the jogger who runs like he’s trying to outrun a clock no one else can hear. The wind chimes tinked. The jasmine hadn’t woken up yet for the season but it was thinking about it.

“Do you ever feel sorry for her?” Romy asked, not meaning Mom.

I thought about the lavender coat, the courtroom, the steps. I thought about the image of herself my sister had inherited and sharpened and how it had cut her, too. “Sometimes,” I said. “And sometimes I don’t have the luxury.”

Romy nodded. “You don’t owe anyone a version of you that keeps them comfortable,” she said, and I wanted to stitch it on a pillow, then burn the pillow, then memorize the sentence.

I slept that night in Mom’s room with the window open three inches and the scarf on the back of the chair and in the middle of that dark I woke up and felt, not for the first time, that the house did not mind me being where I was. That it did not prefer me to someone else. It simply wanted someone to keep it, and I was willing.

Spring arrived with drama like it always does. The hydrangeas went from skeptical to full-throated in a week. A letter from the foundation’s chair landed with an ink signature instead of a typed one: We’d like you to consider the board. I said no for now and meant later. The one-year mark ticked closer. The house counted with me.

On the morning the clause expired, I put on a plain white dress and flat shoes because that’s who I am and I walked out the front door and locked it behind me and I stood on the top step and I took the photograph I had never taken: the house behind me, mine in a way no piece of paper had ever made it feel.

A small cheer went up from the sidewalk. Luanne. Janette. Tommy. Romy. Aunt Dolores, chin lifted like a general who finally gets to serve tea. “We brought muffins,” Luanne called, holding up a tin like an offering.

“Of course you did,” I said, and laughed until my face hurt.

We ate on the front steps because we could. People we didn’t know stopped and said congratulations like the house had graduated. It had. So had I.

In the afternoon, I went inside and took the pale blue envelope from my dresser—the one that had come to me singed and held more than it looked like it could. I folded Mom’s letter along its old crease and slipped it back in. I wrote on the front, beneath To my youngest, my silent warrior: Home.

Then I took out a new piece of paper and wrote to nobody and to everybody: You don’t get to write me out. I tucked it into the scarf’s hem where the key had been because some places deserve to be used twice.

When the porch light clicked on that evening, I sat with Romy and listened to the cicadas and watched the hydrangeas hold their own under the weight of their bloom, and I thought about all the rooms where I’d been quiet, and all the rooms where I’d been loud, and how this was neither. This was steadiness.

The clause had asked me to stay. I had. The house had asked me to listen. I had. The court had asked me to prove. I had.

The rest was up to me.

Part V

If you’ve never signed a deed and known you’re signing more than a piece of paper, let me tell you: a pen can feel like a plow.

Whitlow brought the final documents in a folder so ordinary you could miss it. “This is it,” he said, spreading the pages like a magician showing there’s no trick. “Title vesting. Trust distribution schedule. Your appointment as trustee for the foundation’s operating endowment. You can decline that last one.”

“I’ll accept,” I said. “With conditions.” He smiled like he’d been waiting for that sentence.

We wrote them together at the kitchen table where I’d eaten cereal as a child and secrets as a teenager: no family officers; community seats with voting power; a standing fund for school librarians to order what they knew their students needed without permission from people who had never shelved a book. We added a line that would have made Mom clap: Annual report written in plain language distributed to the donors, the staff, and the public. We christened it the Marin Plain-Language Rule and Whitlow underlined it twice like he’d fought harder for less important things.

The board ratified it in a meeting where people brought snacks and the chair wore a tie because he thought he should. Janette cried except she didn’t, which is how nurses cry. Kalista did not attend. The minutes recorded the absence without editorial, and that was mercy.

A month later, I stood in the school library on Congress Street where Mom used to drop off boxes of books like contraband and watched a boy with hair falling in his eyes check out a graphic novel that made him grin big enough to show his molars. The librarian—a woman who had lived long enough to pronounce my name right on the first try—came around the desk and hugged me and said, “She would’ve liked this,” and I said, “She would’ve pretended she did, then dug into every policy that made it hard,” and we both laughed because some ghosts have punchlines.

Kalista isn’t a ghost. She lives ten minutes away in a smaller house with a tinier porch and a more decorative life than she wants. I know this because Charleston knows everything. I ran into her once at the market when I needed tomatoes and she needed a stage. She wore black like she was in mourning for a concept.

“You got what you wanted,” she said. No greeting, no pretense. “You always did.”

I could have told her the list of things I hadn’t gotten, starting with a mother who halfway through our life together stopped making me her person and started making me her plan. I could have told her how expensive victory is when you pay for it in attention. Instead I said, “I got what Mom wanted,” and walked to the next stall and bought freesia out of season because you’re allowed to.

Dad calls on Sundays now. He asks if the hydrangeas are still showing off. He brings Elena over with lemon bars that stick to the napkin in the way that means they’re right. We sit on the back steps and talk about small things and then sometimes he says a big thing like, “I’m sorry I didn’t see you,” and I say a big thing back like, “I know,” and we don’t make those sentences carry too much.

On Tuesdays, the neighborhood still comes for soup. We rotate kitchens. We’ve learned each other’s allergies and arguments. There’s a little boy who always asks me, “Is this your house?” like a lawyer in training. I tell him, “It’s ours,” and his mother nods, and that’s not metaphor; that’s policy.

The court cases became past tense. The addendum lived in the minute book. The anonymous complaints to the county stopped when I installed cameras and put up a sign that said You are being recorded because even grown-ups sit straighter in class when you say it out loud. The house—like most old things that have outlived the people who thought they owned them—taught me this: perfection is a form of neglect.

On the one-year-and-a-day mark, I took down the old portrait from the dining room wall. Not as an erasure. As an edit. I rehung it in the hallway that leads to the sewing room so that every Thursday when we open the house to the public for the local history series, people will walk by her and she’ll hear them say things like we didn’t know and look at that and my mother had that chair and she’ll recognize the heart of what she wanted: to matter in ways that lasted longer than lilies.

That night, after the last guest left and the dishwasher hummed (a miracle; I will never be casual about machines that do their job), I took the scarf out of the drawer and sat at the kitchen table and wrote Mom a letter because grief isn’t a project; it’s a correspondence.

Dear Mom, I wrote. I kept it functional. You’d like the library now. The lace doilies are in a box labeled “Sunday Best” and I only take them out when Luanne comes because she thinks they’re fancy. Kalista lost in court and I didn’t gloat. Aunt Dolores says your hydrangeas are smug this year. I think they’re proud. Thank you for the addendum. It saved us all from worse versions of ourselves.

P.S. I hung your portrait where the kids will see it. I’m learning how to be stubborn in the same direction for a long time.

I folded the letter and put it in the scarf’s hem where the key had been and stitched three messy little anchors to keep it there. It felt like a small spell. It felt like a thing women do in kitchens when no one is watching that still changes a house.

The next morning I walked out the front door—because that’s my door now—and the jasmine tried to steal my perfume and I let it. I walked to the foundation office where the new executive director—smart, quiet, mean when it matters—had already made a list of rural schools whose libraries are losing their shelves to budget. We spent three hours drawing circles on a map and promising paper to children we’ll never meet. We wrote letters to donors who believe good letters can fix bad systems. We wrote checks because sometimes checks are the only thing that moves a brick.

On the way home, a woman stopped me on the sidewalk. I knew her face from somewhere church-adjacent. She had the posture of someone who’s apologized enough to forget she doesn’t have to anymore. “My sister tried to sell my mother’s house while she was in rehab,” she said. “We didn’t have proof. We didn’t have…you.”

“You have you,” I said, which sounded simple and also like the most expensive sentence I’ve learned to say. I gave her Whitlow’s card and Janette’s number and my Tuesday soup invitation. I did not give her my quiet. That’s mine.

The press moved on because they always do. A new scandal grew where an old one had been watered. Sometimes a tourist stops and takes a picture of the house because it looks the way Charleston likes to look: historic, blooming, gentle. They don’t see the patched soffit, the nail you have to talk to, the ledger in the drawer, the letter in the scarf. They don’t have to. That’s my story to be boring about. I like being boring about it. It means nothing is on fire.

People have asked if I forgave her. I tell them forgiveness is a door you can open when you don’t need the lock anymore. Some days it’s a jar. Most days it’s closed. On good days it’s a screen door that lets air in but keeps the bugs out. On bad days I look at the lavender coat in a photograph online and think about how humor is a shield and then go to the kitchen and make soup.

Mom doesn’t visit me in dreams the way people say the dead do when the living need permission. She visits me by making hydrangeas too heavy for their stems and forcing me to stake them, by making the porch groan until I get the jack and the wood blocks out, by making the front door swell in summer so I can use my hip like she taught me. She visits me by refusing to make herself metaphysical. Good. I need her practical.

On the anniversary of the day the envelope arrived in Atlanta, I stood in the foyer with the scarf in my hands and the letter stitched inside and I held them like a plow, like a pen, like a thing you use to make a line where a line should be. I thought about the girl who packed a bag and drove toward magnolia and salt. I thought about the woman who opened a blue envelope on a striped terrace and spoke her mother’s words out loud. I thought about silence—mean, kind, earned, weaponized. I thought about how mine sounds now: like wind chimes on a summer night.

Romy came in through the back with an armful of grocery bags and said, “You ready?” like she always does when the next thing is ordinary and necessary.

“No,” I said, smiling. “But I’m done.”

We ate soup with Luanne and Janette and Tommy and Aunt Dolores at the kitchen table while the dishwasher hummed and the house held us up. We told stories that were smaller than wills and bigger than gossip. We washed dishes in the sink even though the machine works because sometimes you need to do a thing with your hands to understand you’re alive.

When we were done, I walked out onto the porch and leaned on the banister we’d sanded last summer and I watched a girl down the block build a sidewalk chalk empire and I said, to the air and to the woman who made me and almost unmade me, this is a legacy.

Not the portrait. Not the line on the deed. The Tuesday soup. The Friday porch. The hydrangeas stubborn in their blooming. The quiet that doesn’t fold me small. The front door opening because I decided it would.

That’s the thing about legacies built on lies. They end. The ones built right don’t. They just become ordinary, and then you get to live in them.

— THE END —

News

Cheating Wife Packed Her Stuff And Said, You Didn’t Want To Open Our Marriage So I’m Taking The Kids… CH2

Part I At twenty-seven, I thought my life was a line you could draw with a straightedge. Career in a…

At The Work Party, My Pregnant Wife Leaned Over To Her Boss & Said, “He’s My Work Husband,… CH2

Part One: Love doesn’t survive splinters. It can live with dents and scratches and a cracked tile or two, but…

My mom slipped a gold necklace into my 15-year-old daughter’s bag and got her ARRESTED for shoplifti… CH2

Part One: The bench outside the juvenile intake room was too small for any grown-up to sit on without looking…

I Inherited a Stranger’s House by Mistake. The Real Heir Changed My Life Forever… CH2

Part I I was halfway up a ladder in the back of Murphy’s Hardware, stripping rotten trim from a second-story…

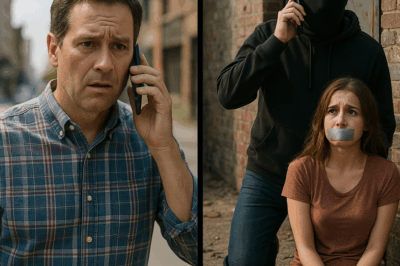

A trafficking ring took my daughter and told me to forget her, They didn’t know who I was… CH2

Part I The morning sun spilled into my kitchen as if it had someplace important to be. It turned the…

My Nephew Came Through a Snowstorm Carrying a Baby: “Please Help, This Baby’s Life Is in Danger!… CH2

Part One: The wind battered Harry Sullivan’s old farmhouse as though the storm had a grudge against him personally. Snow…

End of content

No more pages to load