My parents sued me over a truck.

Not totaled it. Not crashed it into a church or used it to rob a bank. They sued me for owning it.

A 2021 Ford F-150 Lariat. Magnetic gray. 3.5L EcoBoost. Leather so soft it felt illegal. Sticker price seventy-eight thousand four hundred dollars, which was more money than my entire childhood had seen in one place.

I had the keys for three weeks before I got served.

The process server found me in a trailer in the middle of nowhere Wyoming, where the wind never stops and the dust finds every crack in the world. He knocked on the metal door with two quick raps and the whole wall rattled, diesel heater droning in the corner.

“Ethan Hayes?” he called.

It was six-thirty at night, but out there it’s always either too bright or too dark. I was still in my FRs, hands raw from pulling spools of pipe, smelling like 7018 rod and stale Red Bull.

“Yeah,” I said, opening the door, expecting a vendor, a safety guy, anybody but what I got: some guy in a Carhartt jacket holding a manila envelope like it was radioactive.

“Got some paperwork for you,” he said. “You’ve been served.”

It was colder outside the trailer than inside the fridge. My breath smoked. His didn’t, like he was some demon from a warmer place.

I took the envelope, signed where he pointed, and shut the door with my boot. The diesel heater rattled and hummed. Fluorescent light overhead flickered like it was dying on me in slow motion.

I sat down at the little Formica table, tore the flap open with my calloused thumb, and pulled out a stack of stapled pages.

DISTRICT COURT, ARAPAHOE COUNTY, COLORADO

ROBERT AND DIANE HAYES, PLAINTIFFS,

v.

ETHAN HAYES, DEFENDANT.

The caption blurred for a second. I blinked hard. Read it again.

Demand for declaratory judgment. Transfer of title. Attorney’s fees.

I skimmed lines until one sentence punched me square between the eyes:

“Defendant must surrender title to the 2021 Ford F-150 Lariat, VIN (redacted), to Jordan Hayes, age 26, as previously agreed within the Hayes family.”

I read it twice under that buzzing, half-dead fluorescent, diesel heater coughing in the corner, wind trying to rip the trailer up by the skids.

Then I laughed.

Big, ugly, from-the-gut laugh. The kind where your stomach clenches and your ribs hurt. I laughed so hard the chair creaked under me. Because it was so stupid, it had to be a joke.

My own father’s signature stared back at me from the bottom of the complaint.

My mother’s neat little cursive on the verification page, swearing under penalty of perjury that her statements were true.

The laugh twisted in my chest and came out wrong the next time. Less ha-ha, more something that burned on the way up.

When it finally died, I sat there listening to the heater thrum and thought, Of course. Of course they did.

My name is Ethan Hayes. I’m thirty years old, pipefitter welder, UA Local 208. I spent eight straight years putting in eighty-hour weeks in the Bakken and the Permian while my family pretended North Dakota was another planet and oilfield money didn’t spend the same as theirs.

And until that moment, some dumb part of me still believed that if you never asked for anything, never complained, never made waves, your family would at least leave you your scraps.

Turns out scraps are still too much when the golden child is hungry.

We grew up in a 1970s split-level in Aurora, Colorado, the kind every other street had a copy of. Orange carpet that never stopped smelling like old cigarette smoke, wood paneling that absorbed every argument and gave nothing back.

Dad—Robert Hayes, retired Air Force Master Sergeant—ran the place like basic training, except nobody ever graduated. Chores had inspections. Grades were missions. Failure was met with a lecture you could hear three doors down.

Mom—Diane—worked part-time at a dentist’s office and full-time as Dad’s translator. She’d soften the edges, turn “You’re a disappointment” into “Your father just wants the best for you” with this sad little smile that made you wonder if maybe you were the problem.

Jordan arrived when I was four, all red face and shrieking lungs. From that second on, the gravity in our house shifted. Everything that mattered got pulled toward him.

I was the practice kid. He was the real one.

At eight years old, I was pushing my dad’s old Craftsman mower up and down three neighbors’ lawns every Saturday, getting paid in wrinkled fives so I could buy jeans that didn’t have last year’s holes.

Jordan at eight got a PlayStation “because he’s sensitive” and Dad wanted him to “have something to take his mind off things.”

Off what, exactly, nobody ever explained.

At fourteen, I came home from school and went straight to the fryer at a burger joint, flipping patties until midnight. My shoes smelled like grease no matter how many times I hosed them off.

Jordan at fourteen got a used Mustang with a dented quarter panel and a straight pipe exhaust because “he needs to build confidence with girls” and “high school is tough enough.”

Confidence. Must be nice.

At eighteen, I graduated, threw my cap in the air, and walked out of that orange-carpet house with a duffel bag, a busted Civic I’d kept alive with junkyard parts, and four hundred dollars in my checking account.

Dad shook my hand at the door. No hug. No “I’m proud of you.”

“Don’t come crying to me when that piece of shit Civic dies,” he said. “You wanted to go be a big shot. Go be one.”

Jordan at eighteen got handed keys to a brand-new 2017 Ram 1500, red, chrome everywhere, plastic still on the seats. “College is stressful,” Mom said, teary and radiant. “He needs reliable transportation.”

The Ram lasted six months.

He wrapped it around a telephone pole doing ninety-five in a forty-five after a party. Airbags saved his ass. Police report said “alcohol may have been a factor.” Dad called me at three in the morning from the ER.

“Your brother’s gonna need another truck,” he said, like he was telling me we were out of milk.

“You serious?” I croaked, sitting on a bunk bed in a man camp that smelled like feet and diesel.

“You’re doing good up there, right?” he went on. “You can help.”

I sent twelve grand. Every overtime hour I’d worked that winter. Dad never said thank you. Just, “Jordan appreciates it.”

Jordan texted me a thumbs-up emoji.

That was our dynamic. I bled and bent and picked up extra shifts. Jordan drifted, crashed, got bailed out.

I didn’t like it. I didn’t talk about it. I just kept my head down and welded.

The oilfield will take everything you let it: your time, your back, your sleep, your relationships. Guys burned out at twenty-five, divorced at twenty-six, dead at thirty.

I made a deal with myself early on. No bars, no blow, no buying a new pair of boots until the old ones literally flapped. Coffee, energy drinks, tool upgrades only when I could pay cash. Every per diem check went into a high-yield savings account. Every tax return went straight at debt.

Winters in North Dakota, the wind cut through your Carhartt like it wasn’t there. I’ve watched a thermometer sit at minus forty for days, Exposed skin goes from pink to white to black if you’re stupid. I thawed my hands over forty-gallon drum fires more times than I can count, feeling that hot ache spreading into my bones and thinking, someday. Someday this will be worth it.

By March 2024, I had ninety-two thousand dollars in that account and an 810 credit score nobody in my family believed was real.

I took two weeks off and drove home, my old Civic rattling on I-25 like every mile was a negotiation. I parked under a billboard for Frontier Ford and stared at it until my throat tightened.

Screw “someday.” It was time.

The dealership smelled like rubber and finance guy cologne. Bright lights, polished floors, salesmen with too-white smiles.

I walked in wearing work jeans, hoodie, steel-toed boots still stained with rig mud. One of the salesmen glanced up, saw the oilfield beard, the scar on my cheek from a grinder, and looked past me like I was there to use the bathroom.

Another guy, younger, came over anyway. “Can I help you out, bud?”

“I’m here for a 2021 F-150 Lariat,” I said. “Magnetic gray, 3.5 EcoBoost. I know you have at least one that’s not spoken for. Premium package. FX4 if you’ve got it.”

He blinked. “Uh… you looking to trade something in?”

“No trade,” I said. “Just need to know the out-the-door.”

That got his attention.

Sticker on the one I wanted read $78,400. Every option that mattered and none of the fake ones. Heated and cooled seats. Remote start. Big screen in the dash that looked like a tablet had married a spacecraft.

We went back and forth once on the price, just so he’d feel like he’d done his job. Then I slid fifty thousand dollars in cashier’s checks across the desk and told him to finance the remaining $28,400 at whatever best rate he had.

He came back with 3.9%.

“Title in my name only,” I said. “No co-signers. Nobody else.”

He looked almost disappointed. “You sure you don’t wanna add a cosigner? It can help your rate.”

“I’m sure,” I said. “Nobody’s name on that paper but mine.”

When they handed me the keys, I sat in the driver’s seat for a full minute before starting it. The plastic was still on the door sills. It smelled like fresh leather and new beginnings.

The gauge cluster lit up. The big screen did its little boot-up animation. I set the driver profile to my height, my seat position, my radio presets. The steering wheel warmed under my hands.

Eight years of eighty-hour weeks.

Eight years of frostbite scares, blown knuckles, missed holidays.

Eight years of sending money south to fix problems I didn’t create.

It was all humming under my right foot when I pulled off the lot.

I should have driven straight back to North Dakota. Should have taken it to a storage unit and left it there, a secret between me and the bank.

Instead, I pointed the nose toward Aurora.

I can still see Jordan on that porch.

It was a Sunday, sky clear, mountains sharp on the horizon. The house looked smaller than I remembered, more tired. Same peeling trim. Same crooked basketball hoop over the garage with no net.

Jordan was on the front steps at noon, hoodie hood up, weed smoke curling around his head like incense. He wore the same Colorado Rockies hoodie he’d had for three winters straight. The thing probably held more THC than cotton at that point.

He lifted his head when he heard the turbo whistle. His eyes locked onto the Ford like a coyote spotting a lame calf.

He walked down the steps as I pulled to the curb, slow, like he was trying not to spook it.

“Holy shit, bro,” he said, hands already out. “That’s mine.”

I laughed, good mood making me generous. “Negative.”

He circled the truck, fingers trailing over the paint, leaving little half-moons of grime on my brand-new clear coat. Opened the door without asking, climbed in, put his hands on the steering wheel like it was a prayer.

He adjusted the mirrors. Tilted the seat back. Flipped down the visor and took a selfie, angle just right so the emblem on the wheel and the stitched leather were in frame.

He’d posted it before I even shut my old Civic off.

I saw the notification pop on his screen: Big bro finally came through. Appreciate you ♥️ blessed new whip.

“Delete that,” I said.

He looked at me, smirked, thumb already moving. “Relax. Just playing.”

He deleted it. Or pretended to. I didn’t care enough in that moment to check. I was dizzy on the smell of my truck and the idea that for once, I had something nice.

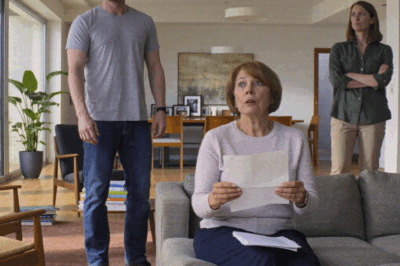

Mom came out wiping her hands on a dish towel, hair up, eyes already shiny.

“Oh, Ethan,” she breathed, pressing her fingers to her lips. “Oh, honey, it’s beautiful.”

She hugged me tight, asked to sit in it, touched every button like she was afraid to break it. Took a hundred pictures. Turned to Jordan, face full of hope.

“Can you imagine your brother driving you to your job interviews in this?” she said.

Job interviews that didn’t exist, for a job he didn’t have.

Dad was on a double shift that day. Part of me was relieved. I’d spent my whole life reading his reactions like weather reports.

We grilled burgers that night. Mom fussed over me like I’d come back from war. Jordan made jokes. For a few hours, sitting at that wobbly patio table, paper plates bending under potato salad and hot dogs, it felt almost… normal.

When I left, Mom hugged me hard enough to creak my ribs. Jordan slapped the side of the Ford.

“Just make sure it’s still sexy when I get it,” he said, half-joking, half not.

“You’re not getting it,” I said.

He rolled his eyes like I’d told him he couldn’t have the last slice of pizza.

Driving back to my rental that night, I let myself think, Maybe this is turning a corner. Maybe they finally see I’m not just the practice kid who left.

Monday morning, Jordan proved me wrong.

I found out about the post because my foreman texted me a screenshot.

I was sitting in a work truck outside a Maverik gas station in minus-twelve-degree weather, waiting for a roustabout crew to finish using the only functioning air pump in a hundred miles. I had the heater on full blast, windows still fogging.

My phone buzzed.

It was a photo of Jordan in the driver’s seat of my truck, same shot as before, my plates visible: ETHAN1.

Caption:

“When your brother takes the self-made man route, uses the $50,000 grandpa secretly promised me for my first real truck and buys himself the exact one I showed him on my vision board. Real classy, Ethan. Some of us are still struggling with student loans and mental health, but go off I guess.”

Tagging: me, my employer, my union local, my high school ex.

2,847 likes in the first twenty-four hours. Comments stacked under it like a wall of vomit.

Wow, what a selfish prick.

Typical oldest child syndrome.

Prayers for Jordan, stay strong king.

That’s disgusting behavior. YOU DESERVE BETTER JORDAN 💔

People I hadn’t spoken to since sophomore year of high school crawling out of the woodwork to call me a piece of shit.

My hands shook. Not from the cold.

I called him.

He didn’t pick up.

I called again. Third time, he answered.

“What’s up, bro?” he said, sounding bored.

“What the fuck is that post?” I snapped. “Take it down. Now.”

“You mad?” he asked. I could hear the smile.

“You lied, Jordan. Grandpa never—”

“It’s not a lie if that’s how I feel,” he cut in. “You knew that money was always meant for me. Everyone knew it.”

“There wasn’t any money,” I said. “We each had ten grand in UTMAs and I left mine alone while you blew yours on raves and jewel pods. And even if there was, this truck is mine. I paid for it.”

He made a fake sympathetic noise.

“Aww, big man with his overtime checks feeling threatened,” he said. “Maybe next time don’t flex on Instagram with your big boy toy when your family’s struggling.”

“I never posted it,” I said. “That was you.”

He snorted. “Semantics. Look, I gotta go. Mental health day.”

He hung up.

Two minutes later, my dad called.

I stared at the screen, thought about letting it ring, and answered anyway.

“Son,” he said. His voice was flat, controlled. Dangerous. “We’re disappointed.”

Another we. Mom and Dad, a matched set of disapproval.

“That truck was understood to be for Jordan when he gets on his feet,” he went on. “You knew that.”

“There was never any such understanding,” I said. “I paid for it. Every cent. You didn’t give me a dime.”

“We’ve retained counsel,” he said, like he was telling me he’d picked up milk. “You can sign it over quietly or we’ll see you in court. Your choice.”

He hung up.

No “how are you.” No “we need to talk about this.” Just a threat over a truck that had my name on the title and my blood in the paint.

I sat there in the parking lot of that Maverik, snow swirling in the wind, my coffee going cold. The process server showed up that night like clockwork.

Now I had the complaint in my hands, and my name was on the wrong side of the v.

The complaint was a masterpiece of bullshit.

Count I: Breach of Oral Agreement. Alleged that “within the Hayes family” it was “understood” that any “major vehicle purchase” by the eldest son would be transferred to the youngest upon his need for “career advancement.”

Count II: Constructive Trust. Alleged that my purchase of the truck with “monies expected by the family” for Jordan’s benefit amounted to unjust enrichment.

Count III: Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress. Jordan, they claimed, suffered “severe anxiety” and “nightmares” knowing “his promised truck” was in my possession. He couldn’t sleep. He drank. All my fault.

Relief requested: transfer of title to Jordan Hayes, attorney fees, costs, “and such other relief as the court deems just and proper.”

I didn’t know much about law. But I knew what it felt like to be stabbed in the front.

I found a lawyer the next day.

Her name was Sarah Delgado, mid-forties, sharp suit, sharper eyes, office on the fifth floor of a building in downtown Denver that smelled like old paper and new coffee. Hispanic, hair tied back in a no-nonsense knot. Diplomas on the wall, fifteen years of practice in civil litigation.

I slid the complaint across her desk.

She read it once, eyebrows climbing. Then she leaned back and let out a low whistle.

“This is the most batshit thing I’ve seen in fifteen years of practice,” she said. “And I’ve represented people who sued over a stolen ferret.”

I almost laughed. Almost.

“Can they do this?” I asked.

“Anybody can sue anybody for anything,” she said. “Winning is another matter.”

She tapped the complaint.

“This is garbage,” she said. “There’s no writing. No documentation. They claim an ‘oral contract’ that doesn’t pass the smell test. ‘Family expectation monies’ isn’t a legal term. They’re hoping you’ll roll over to avoid the drama.”

I thought of my dad’s voice on the phone, cold as a January drill floor. “We’ve retained counsel.”

“I’m not rolling over,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “Because we’re going to ruin them.”

She had me walk her through everything. The UTMA accounts Grandpa had set up when we were kids. The twelve grand I’d wired after Jordan totaled his Ram. Every job I’d worked. Every deposit into my Ally high-yield savings.

“Send me every bank statement you have for the last ten years,” she said. “Online, PDF, snail mail, I don’t care. I’m going to bury their ‘family expectation’ in actual math.”

“Can I… counter-sue?” I asked. The word tasted strange.

“Let’s win first,” she said. “Then we’ll talk about sanctions and fees.”

Discovery is a polite word for strip search.

Their attorney—some smug country club type named Whitaker who golfed with my dad on Thursdays—sent subpoenas to every bank I’d ever used. Local credit unions. Ally. The little North Dakota bank that issued my first debit card.

He was looking for anything he could twist into “seed money.” A deposit from Mom that looked like more than birthday cash. A transfer from Grandpa’s estate marked “truck fund.”

There was nothing. Grandpa had left ten grand to each of us. Mine sat untouched until I paid for trade school. Jordan drained his fifty bucks at a time for festivals and weed.

They subpoenaed my co-workers, too.

One guy on my crew texted me a picture of the subpoena. “These clowns serious?”

Whitaker’s questions were laughable.

Has Ethan ever bragged about getting the truck dad promised Jordan?

Has Ethan ever admitted to stealing family funds?

My foreman, a guy named Mark with thirty years of pipeline under his belt and zero tolerance for bullshit, sent back a one-line statement.

“Ethan’s the hardest working kid I know, and his parents are deadbeats who never visit.”

Sarah framed that.

We deposed Jordan first.

He showed up in a $400 Canada Goose jacket I’d bought him for Christmas two years earlier, white sneakers too clean to have walked much real ground, hair perfectly tousled. Carried a stainless steel water bottle with stickers that said things like MENTAL HEALTH MATTERS and GOOD VIBES ONLY.

Under oath, you’d think he’d show a little humility.

“State your name for the record,” Sarah said.

“Jordan Hayes,” he said, voice small. He glanced at the camera like it was an audience.

“How old are you, Mr. Hayes?”

“Twenty-six,” he said.

“You live with your parents?” she asked.

He looked offended. “I live at my parents’ house, yes. Temporarily. I’m between opportunities.”

“I see,” Sarah said. “And you currently drive…?”

“I don’t have a truck because of Ethan,” he said, staring at me. “I borrow Mom’s Suburban sometimes.”

“He lives rent-free,” I muttered. Sarah squeezed my arm under the table.

“Mr. Hayes,” she said aloud, “you’ve alleged that your brother ‘used the $50,000 grandpa secretly promised you’ to buy his truck. Do you have any documentation of that promise?”

“It was understood,” Jordan said. “Grandpa told me when I was like twelve that my first real truck would be from him. He always said I was his little cowboy.”

Sarah slid a stack of statements across the table.

“These are UTMA account statements,” she said. “One for Ethan, one for you. You each had ten thousand dollars. Do you recognize the withdrawals from your account?”

He glanced at them. Shrugged. “Probably college stuff,” he said.

“Is ‘Electric Daisy Carnival Tickets’ college stuff?” she asked.

He bristled. “That was a hard year for me.”

She didn’t roll her eyes. I did.

She asked about the Ram. The pole. The night in the ER. He cried on cue when he talked about how “traumatizing” the accident had been, how unfair it was that “now, when I’m finally ready to do something with my life, Ethan won’t help.”

Then Sarah played the Ring doorbell footage.

There he was, 2:14 a.m., stumbling up to my apartment complex parking lot, hoodie up. He tried the handle on my truck. Locked. He popped the hood, fumbled around like he had any idea what he was doing. Tried to hotwire it for a minute, failed spectacularly.

Finally, he stepped back, looked around, and pulled his keys out. Dragged them down the driver’s side door in one long, angry scrape.

Four thousand two hundred dollars in damage.

“Was that a prank?” Sarah asked.

Jordan swallowed. “Yeah,” he said. “Just messing around. I would’ve paid him back when I could.”

“He never said a word to me,” I said under my breath.

Mom’s deposition was worse.

She came in with tissues already in hand, pearls on, cardigan buttoned to the throat. She dabbed her eyes every time she said the word “Jordan,” even when no tears came.

“Mrs. Hayes,” Sarah said, “you’ve testified that Ethan has ‘always been cold and distant.’ Can you give an example?”

“Well,” Mom said, sniffing, “he left home at eighteen and never looked back. Jordan needed his big brother. He was always so sensitive. And Ethan just… abandoned us.”

“I sent twelve thousand dollars when Jordan totaled his truck,” I said. “That’s not abandonment.”

“Please don’t address the deponent directly,” Whitaker snapped.

Sarah let Mom talk.

She painted Jordan as a fragile angel: depression, anxiety, “mental health struggles.” Talked about how he “needs the truck to get to therapy appointments” twelve miles away.

“And why not buy him a fifteen-thousand-dollar used truck if transportation is the issue?” Sarah asked, voice mild.

Mom looked at her like she’d suggested feeding Jordan dog food.

“That wouldn’t be fair to Ethan,” she said.

“Explain,” Sarah said.

“Well, Ethan worked so hard for his education,” Mom said. “It wouldn’t be right for Jordan to get something cheaper. It’s only fair that he gets the nice truck, too.”

“Something cheaper than a seventy-eight-thousand-dollar Ford?” Sarah asked.

Mom nodded, earnest. “Besides, Ethan can always earn more,” she said. “Jordan cannot.”

There it was. Laid bare on the record.

Dad was last.

He walked in wearing an American flag polo shirt tucked into creased jeans, belt buckle big enough to pick up radio stations. Sat ramrod straight. Called the court reporter “ma’am” and Sarah “young lady.”

“Mr. Hayes,” Sarah said, “you’ve testified that there was a ‘family understanding’ about trucks.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “I told Ethan when he was sixteen, ‘One day when you make it, you’ll buy your brother a proper truck like I never could.’”

I actually laughed. It escaped before I could stop it.

“What did he say?” Sarah asked.

“He said, ‘Yes, sir,’” Dad replied. “Like a good son.”

He never said any such thing. At sixteen, I’d had a Civic with three different colored panels, and all he told me was not to come crying when it died.

Sarah didn’t argue with his memory. She pulled out the dealer paperwork.

“You recognize this?” she asked.

He squinted. “Looks like a purchase agreement,” he said.

“That’s right,” she said. “For the 2021 Ford F-150 at issue in this case. Do you see this line? ‘Cash down payment: $50,000 from Ally Bank account ending in 4209.’”

He nodded.

“Have you ever deposited money into that account?” she asked.

He shifted. “No, ma’am,” he said.

“Has your father—Ethan’s grandfather—ever deposited money into that account?” she asked.

“He didn’t need to,” Dad said quickly. “It was understood. The money was there for the family. For Jordan.”

“Understood by whom?” Sarah asked.

“Everyone,” Dad snapped. “Everyone except Ethan, apparently.”

He stared at me like he could still order me to attention from across a conference room under oath.

I stared back and thought, I’m not in your chain of command anymore.

Two nights before trial, Uncle Tim flew in from Phoenix.

Dad’s older brother, sixty-two, retired airline pilot, shoulders like a refrigerator, hands like he could still swing wrenches on a jet at midnight in Anchorage.

He hated Dad’s favoritism since we were kids. Mom always acted like he was the family traitor because he didn’t toe the line around “Rob knows best.”

He showed up in Sarah’s office with a battered briefcase and a stack of files.

“Your grandpa wasn’t perfect,” he said, “but he wasn’t crazy. He didn’t ‘secretly promise’ anybody fifty grand for a truck.”

He had the original 2009 will, yellowing at the edges, with the UTMA accounts spelled out. Ten thousand each, equal. No secret clauses, no asterisks.

He had the UTMA statements themselves—mine showing deposits and no withdrawals until 2012, when I went to trade school. Jordan’s showing $500 and $300 and $700 coming out over two years with not even a note in the memo line.

He had bank records, printouts, emails. The man had receipts before receipts were a thing.

Aunt Karen came, too. Dad’s sister. She’d kept every birthday card Grandpa ever wrote us.

Mine always said some version of, “For Ethan, for when you build your life.”

Jordan’s said, “For Jordan, spend it wisely, son.”

No mention of trucks. No mention of “your first real truck will be from me.”

“Your father heard what he wanted to hear,” Uncle Tim said. “He’s been hearing it since 1999.”

Sarah flipped through everything, her lawyer brain already stitching it into a narrative.

“This is good,” she said. “This is very good.”

I still didn’t sleep much that night.

I lay awake in my cheap hotel room, staring at the textured ceiling, listening to the heater cycle on and off, thinking about Dad’s eyes on the stand, Mom’s tissue dabs, Jordan’s crocodile tears.

Part of me still hoped they’d come to their senses at the last minute. That I’d walk into the Arapahoe County Courthouse and see them in the hallway with Whitaker, papers in hand, ready to settle.

No truck is worth blowing up a family over.

Then I’d remember Mom saying “Ethan can always earn more. Jordan cannot.”

And I’d think, Maybe the family was blown up a long time ago.

I didn’t sleep the night before trial.

I lay on a lumpy hotel mattress off I-25, staring at a ceiling that looked like cottage cheese, listening to semis howl past and the heater cycle on and off. Every time I closed my eyes I saw my dad on a witness stand, raising his right hand and lying through his teeth. Mom dabbing invisible tears. Jordan smirking.

At five-thirty I gave up, showered, shaved, and put on the only suit I owned—a dark gray off-the-rack number I’d bought for a buddy’s wedding and barely worn since. The sleeves were a little short from years of pipe and protein. My work boots didn’t match, but they were the only shoes that didn’t hurt my feet.

I drove downtown in the Civic, because the idea of parking seventy-eight thousand dollars’ worth of truck in a courthouse lot full of people I didn’t trust felt like tempting fate.

The Arapahoe County Courthouse was all glass and concrete, trying hard to look modern and tired anyway. Security wanded me like I might be bringing a pipe wrench of justice. The guard glanced at my hands, saw the callouses, gave me that automatic half-respect working men get from other working men.

“Good luck in there,” he said, handing my belt back.

“Thanks,” I said. “I think.”

Upstairs, outside Department 3B, Sarah was waiting, black suit, red lipstick, leather briefcase that looked heavy enough to swing as a weapon if needed. She handed me a travel mug.

“Black,” she said. “Figured you’re not a pumpkin spice guy.”

“You figured right,” I said, grateful.

I turned and there they were, twenty feet down the hall.

Mom in a cream blouse and pearls, hair sprayed into place, clutching a tissue like a prop. Dad in a flag polo and navy blazer, his medals pinned to the lapel like the judge might award points for service. Jordan in Yeezys and skinny jeans, AirPods in, scrolling his phone like he’d been dragged to a DMV appointment.

Dad’s eyes cut to me, cold as the North Dakota wind. Mom’s mouth trembled. Jordan smirked.

For half a second, some old habit in me wanted to go over, hug my mother, crack a joke with my brother, ask my father what the hell he thought he was doing.

Then I remembered the line in Mom’s deposition.

Ethan can always earn more. Jordan cannot.

I stayed where I was.

“They’re really going through with this,” I said quietly.

Sarah snorted. “Oh honey, they sailed past ‘going through with this’ somewhere back around ‘filed a malicious complaint.’” She patted my arm. “Let’s go win.”

We went in when the clerk called the case. The courtroom was smaller than TV made it look. Wood paneling. State seal over the judge’s bench. Rows of empty seats, except for Uncle Tim and Aunt Karen in the back, sitting stiff and furious.

Judge Harlland took the bench—a big man in his late sixties with a crew cut so tight you could bounce a quarter off it. Former JAG, Sarah had told me. Career Army lawyer. He looked like he’d eaten ten Rob Hayeses for breakfast and hadn’t even burped.

“Call the case,” he said.

“Arapahoe County District Court, Case 25CV—” the clerk began. “Robert and Diane Hayes versus Ethan Hayes, Your Honor.”

“All right,” Harlland said, flipping open the file. He looked at it for maybe three seconds, his face going from neutral to the expression of a man who’d discovered a raccoon in his garbage.

We all stood. We all sat. My palms sweated.

Whitaker stood for the plaintiffs, silver hair, tan like he lived on a golf course.

“Your Honor,” he said, all honey, “this is a simple matter of a family understanding gone wrong.”

He clicked a remote. A projector screen lowered on the side wall. A PowerPoint popped up, title slide in blue letters:

THE HAYES FAMILY UNDERSTANDING

I stared. Sarah actually choked on a laugh beside me and disguised it as a cough.

Slide three was a photo of twelve-year-old Jordan sitting in the driver’s seat of a pristine F-150 in some dealership, grinning like he owned the world. Caption: Dreams Deferred.

I almost walked out.

Whitaker talked about promises and expectations and how “in blue-collar families, agreements are often sealed with handshakes, not paper,” like he’d ever dirtied his hands on anything but a driver.

He said I had “used my advantaged position” and “misappropriated resources intended for my vulnerable brother.” He said this case was about “fairness” and “family.”

Sarah let him go. When he sat down, she stood.

“Your Honor,” she said, “this case is not about fairness or family. It’s about entitlement. It’s about parents trying to use the court system to force one adult son to financially parent another. We will show there was no agreement. No constructive trust. No unjust enrichment. Just a thirty-year-old man who saved his paychecks and bought himself a truck, and a twenty-six-year-old man who thought he was entitled to it.”

She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t click anything. She just looked at the judge like she trusted him to see the truth.

He nodded once. “Plaintiffs may call their first witness.”

Dad went first.

He raised his right hand, swore to tell the truth, sat down like he was back in a promotion board.

“Mr. Hayes,” Whitaker said, “can you tell the court about your relationship with your sons?”

“I’m their father,” Dad said. “I did my best. Provided a home. Food. Structure.”

He looked over at me, eyes hard. “Discipline.”

“Did you have an understanding regarding vehicles in your family?” Whitaker asked.

“Yes, sir,” Dad said. “When Ethan was sixteen, I took him aside. I told him, ‘Son, one day when you make it, you’ll buy your brother a proper truck like I never could.’ He said, ‘Yes, sir.’”

Lie.

“Did your father—Ethan’s grandfather—ever express a wish regarding Jordan’s first truck?” Whitaker asked.

“Yes, sir,” Dad said. “He told all of us he wanted Jordan to have a real truck. Said he’d help. Maybe not in writing, but it was known.”

“Did you believe the funds your father set aside were intended for Jordan’s truck?” Whitaker asked.

“I did,” Dad said.

He talked about Jordan’s “struggles,” about wanting “better for him.” He painted me like some cold-hearted mercenary who’d swept in, snatched the keys out of his little brother’s hand, and sped off laughing.

When it was Sarah’s turn, she didn’t go for his throat. Not right away.

“Mr. Hayes,” she said, “you testified that your father set aside funds for Jordan’s truck. Do you recall how much?”

“About ten thousand each,” Dad said. “For both boys.”

“So equal amounts,” Sarah said. “Not more for Jordan than for Ethan.”

“Grandpa knew Jordan needed more,” Dad said. “He just couldn’t put it in writing. Estate tax.” He said “estate tax” like he’d just discovered the phrase on YouTube.

Sarah slid the UTMA statements onto the evidence cart and handed him a copy.

“These show ten-thousand-dollar accounts for each boy,” she said. “Do you see any notation that Jordan’s account was for ‘truck money’?”

“No, ma’am,” he said.

“Do you see any notation that Ethan’s account was for ‘anything else’?” she asked.

He shifted. “No, ma’am.”

“And you understand that Ethan left his account untouched until 2012, when he paid for trade school,” she said. “While Jordan withdrew his over two years for items such as concert tickets and vacations.”

Whitaker objected. “Relevance.”

“Goes to the credibility of this alleged ‘truck fund,’ Your Honor,” Sarah said.

“Overruled,” Judge Harlland said. His mouth twitched like he was trying not to smile.

Sarah slid the dealer paperwork over.

“This is the purchase agreement for the 2021 Ford F-150, correct?” she asked.

“That’s what it says,” Dad said.

“Do you see this line? ‘Down payment: $50,000 from Ally Bank account ending 4209,’” she said.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“Have you ever deposited any money into that account?” she asked.

“No, ma’am,” he said.

“Has your father?” she asked.

“No, ma’am,” he said. “But—”

“Thank you, Mr. Hayes,” she said. “No further questions at this time.”

Whitaker looked annoyed. Dad looked like he’d expected a fight and gotten a pat on the head.

Mom went next.

She took the stand like she was walking down the aisle at a funeral. Clutched a tissue. Looked at the judge like he was the last good man in the world.

“Mrs. Hayes,” Whitaker said, “how has Ethan’s behavior impacted your family?”

She sniffed. “He’s always been distant,” she said. “He left home at eighteen and didn’t think about how much his brother needed him. Jordan has struggled with depression for years. At nineteen, he tried to… he tried to take his own life.”

I jerked like I’d been slapped.

News to me.

“When he totaled his truck,” Mom went on, “it was devastating. We thought we’d lose him. The only thing that’s helped is the hope that one day he’d have a reliable truck again. It gives him purpose. Something to look forward to.”

Tears finally came. I’ll give her that.

“Why do you believe Ethan should give Jordan this specific truck?” Whitaker asked.

“Because it’s what was promised,” she said. “Because it’s not fair for Ethan to have something so nice while Jordan has nothing. And because Ethan can always earn more. Jordan cannot.”

You could feel the air change on that last line. Even Whitaker winced.

Sarah stood for cross.

“Mrs. Hayes,” she said gently, “you’ve testified that Jordan needs the truck to get to therapy, yes?”

“Yes,” Mom said. “His therapist is twelve miles away.”

“And you and your husband currently own…?” Sarah asked.

“Two vehicles,” Mom said. “My Suburban and my husband’s Tacoma.”

“So if transportation to therapy were the only issue, you could buy Jordan a used vehicle for, say, fifteen thousand dollars, correct?” Sarah asked. “Or co-sign a modest loan?”

Mom blinked. “That wouldn’t be fair to Ethan,” she said.

“Because Ethan’s truck is worth more,” Sarah said.

“Yes,” Mom said. “It would hurt his feelings if Jordan got something cheap.”

Gasps from the back. I heard Aunt Karen’s soft, disbelieving “Oh my God.”

“Mrs. Hayes,” Sarah said, all sugar, “did it hurt Ethan’s feelings when you and your husband sued him for his truck?”

Mom’s lip trembled. “This isn’t about feelings,” she said. “It’s about what’s right.”

Sarah nodded. “No further questions.”

Then it was Jordan’s turn.

He got up there with his AirPods out and his fake-humble face on.

“Mr. Hayes,” Whitaker said, “can you tell the court how your brother’s actions have affected you?”

Jordan took a deep breath like he was about to break into spoken word poetry.

“It’s been… really hard,” he said. “I have nightmares. I see the truck in my dreams. I wake up sweating. I can’t sleep knowing my truck is out there, and I don’t have access to it.”

Your truck.

“I’ve been drinking again because of the stress,” he said. “My therapist says it’s trauma.”

Whitaker nodded sympathetically. “Have you struggled with suicidal ideation?” he asked.

Jordan glanced at Mom. She dabbed her eyes on cue.

“Yes,” he said. “I don’t see the point sometimes. Ethan has everything. I have nothing. It’s hopeless.”

If I hadn’t seen his Instagram from Cancun, I might have believed him. Might have.

When Sarah stood, his eyes narrowed. He tried to smirk and failed.

“Mr. Hayes,” she said, “you currently live in your parents’ basement, correct?”

“It’s a finished basement,” he said, defensive. “It’s basically an apartment.”

“And you pay how much in rent?” she asked.

“Nothing right now,” he said. “Times are tough.”

“You drive your mother’s 2022 Suburban when you need transportation,” she said.

“Sometimes,” he said. “When she doesn’t need it.”

Sarah clicked her own remote. The screen lit up with a familiar Ring video.

“Do you recognize this?” she asked.

Jordan’s face flickered as footage played of him at 2:14 a.m., hoodie up, trying my truck’s door, popping the hood, fumbling around, then keying GIMME down the side.

$4,200 in damage.

He shifted in his seat. “That was just a prank,” he said. “We were messing around.”

Sarah didn’t argue. She clicked again.

The screen showed his Instagram: shirtless mirror selfie in Cancun, sunburned, drink in hand. Caption: Living my best life, no depression here 😎🍻 Posted the same week Mom said he’d tried to kill himself.

“Is this you?” Sarah asked.

Whitaker objected. “Your Honor, social media is not—”

“Overruled,” Harlland said. “He posted it. He owns it.”

Jordan squirmed. “Everyone lies on Instagram,” he muttered.

“One more,” Sarah said. She brought up a TikTok from two nights ago. Jordan in a club, neon lights flashing, throwing cash in the air. Caption: Who needs a truck when you got bottles? Sorry, not sorry Ethan.

The courtroom laughed before anyone could stop it.

“Order!” the judge barked, banging his gavel so hard the water pitcher jumped.

“Mr. Hayes,” Sarah said, “were you aware that this trial was scheduled when you filmed this video?”

“Yes,” he said.

“And you posted it anyway?”

“Yes,” he said.

“No further questions,” she said.

He slid off the stand like he couldn’t get away fast enough.

Then it was our turn.

Sarah called Uncle Tim.

He took the stand like a man reporting for duty one last time. Swore in. Sat down. Stared straight ahead.

“Mr. Hayes,” Sarah said, “how are you related to the plaintiff, Robert Hayes?”

“He’s my younger brother,” Tim said.

“And to the defendant, Ethan Hayes?” she asked.

“He’s my nephew,” Tim said. He glanced at me. His jaw flexed.

“Did you have conversations with your father—Ethan’s grandfather—about how he wanted his assets distributed?” she asked.

“Yes,” Tim said. “In 2009, he told me he was setting up UTMA accounts. Ten thousand each for Ethan and Jordan. Equal. He did not tell me there was anything earmarked for a truck, for either of them.”

“Did you ever hear him promise Jordan fifty thousand dollars for a truck?” she asked.

“No,” Tim said. “If he had that kind of money lying around, he’d have bought it himself just to shut Rob up.”

A few chuckles. Judge didn’t bother banging the gavel this time.

“Did you express concerns to your brother about how he treated his sons?” Sarah asked.

“Yes,” Tim said. He turned in the witness chair, looked Dad dead in the eye.

“In 2012, after Jordan totalled his first car, Dad told Rob flat out that if he kept spoiling that boy, he’d ruin him,” Tim said. “Rob didn’t listen. He kept bailing Jordan out. Kept leaning on Ethan. Now he’s in here trying to ruin the good one to fix the broken one.” His voice rose. “Shame on you, Rob.”

Dad’s face went purple. Whitaker sputtered.

“Objection—”

“Overruled,” Judge Harlland said. “I wanted to say it myself.”

No further questions.

Aunt Karen’s testimony was quieter but made the same point. Birthday cards. Equal UTMA references. No golden truck fund.

Sarah could’ve called me to the stand, but she didn’t need to. The paper trail spoke louder than I could.

When both sides rested, Judge Harlland rubbed the bridge of his nose like his head hurt.

“I’m going to take a brief recess,” he said. “Eighteen minutes. Then we’ll have a ruling.”

We filed out into the hallway. Mom clung to Jordan. Dad stood stiff, staring at the seal on the wall like he could will it to switch sides.

Uncle Tim came over, put a hand on my shoulder.

“No matter what that man says,” he nodded toward the courtroom door, “you did nothing wrong, kiddo.”

I swallowed around a lump in my throat. “Thanks, Uncle Tim.”

Sarah checked her watch. “You holding up?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I feel like if I move too fast, I’ll throw up.”

“Totally normal,” she said. “When we go back in, keep your face neutral. Don’t react. Even if he sings your praises. Judges like stoic defendants.”

“Right,” I said. “I’ll pretend I’m back in the man camp showers when the hot water runs out.”

She snorted.

Eighteen minutes later, the clerk called us back in.

We stood as Judge Harlland took the bench again. He shuffled his papers, looked out over us, and sighed.

“This court has reviewed the testimony and exhibits in Hayes versus Hayes,” he said. “I’m going to give you my ruling from the bench.”

I gripped the edge of the defense table.

“First,” he said, “let me be very clear. I find the plaintiffs’ claims not only baseless, but malicious.”

Whitaker shifted in his seat. Mom’s hand flew to her mouth. Dad’s jaw clenched.

“There is no evidence—zero—of any enforceable agreement requiring Ethan Hayes to purchase a truck for his brother,” Harlland went on. “No writing. No corroborated testimony. At best, there were vague parental wishes. Wishes are not contracts.”

He ticked points off on his fingers.

“Second, there is no constructive trust here,” he said. “The funds used to purchase the vehicle came from Ethan’s own earnings. Not from his parents. Not from his grandfather. He left his UTMA intact until he used it to improve his earning capacity. His brother, on the other hand, spent his on… music festivals.”

He glanced over his glasses at Jordan.

“Third, the claim of unjust enrichment is absurd,” he said. “Ethan Hayes worked eighty-hour weeks for eight years in hazardous conditions, saved his money, and purchased a vehicle in his own name. That is the opposite of unjust enrichment. That is just plain enrichment, the kind we like to see in this country when people work hard.”

My eyes stung.

“As for intentional infliction of emotional distress,” he said, his voice hardening, “the only intentional infliction of anything I see here is the plaintiffs’ decision to drag their son into court over his own property.”

He turned to Whitaker.

“Counselor, you should have talked your clients out of this,” he said. “Instead, you enabled it.”

Whitaker looked like he wanted to sink through the floor.

“Therefore,” Harlland said, drawing himself up, “the plaintiffs’ complaint is dismissed with prejudice. The 2021 Ford F-150 Lariat at issue is unequivocally the property of Ethan Hayes. Title and possession remain with him. Furthermore, the plaintiffs are ordered to pay the defendant’s attorney fees in the amount of eighteen thousand, seven hundred forty-two dollars and court costs.”

Sarah’s fingers tightened on my arm. I exhaled for what felt like the first time all day.

“And one more thing,” the judge said. “This matter is referred to the district attorney’s office for potential perjury investigation. Several statements on the record today do not square with the documentary evidence.”

He looked straight at Mom and Dad when he said it.

Mom went pale. Dad’s nostrils flared.

Finally, Harlland turned his gaze on Jordan.

“Young man,” he said, “you are twenty-six years old. You live rent-free. You drive other people’s cars. You spend money in nightclubs while your brother works in subzero temperatures. And you came into my courtroom asking me to take his truck and give it to you because you ‘need it more.’”

Jordan opened his mouth. Closed it.

“Get a job,” the judge said.

Gavel. Boom.

Case closed.

The hallway outside the courtroom felt different on the way out. Lighter, somehow. Or maybe that was just the absence of that crushing uncertainty.

Mom was crying for real now, mascara streaking. Dad’s face was red, not from embarrassment but from anger. Jordan looked like a kid who’d just been told Christmas was canceled because Santa got drunk.

They intercepted me before I reached the elevators.

“You think you won?” Dad said, stepping into my path, veins bulging in his neck. “You just destroyed your mother.”

I looked at her. She clung to his arm, eyes wet, lower lip trembling.

“No, Dad,” I said, surprised at how steady my voice came out. “You did that when you taught Jordan the world owes him my paycheck.”

“How dare you—” Mom started.

“You sued me,” I said. “Over something I earned. In front of strangers. You lied under oath. And you’re worried about my daring?”

“How are you going to live with yourself?” Mom wailed.

“Better than I lived with you,” I said.

Jordan stepped in close, smelling like expensive cologne and secondhand smoke.

“This isn’t over, bro,” he said, shoving my shoulder.

Eight years ago, I’d have let it slide. Fourteen years ago, I’d have apologized.

Not this time.

I stepped into him, not back. I’m not huge, but I’ve spent a decade moving steel and swinging hammers. He bounced.

“You touch my truck again,” I said quietly, “and I’ll have you charged with felony criminal mischief. You touch me again, and I’ll break your hands.”

His eyes widened. Just for a second. First time in his life he looked at me and saw someone who could hurt him.

Dad glared. “You threatening your own brother?” he barked.

“I’m setting boundaries,” I said. “Something you should’ve done twenty years ago.”

Sarah appeared at my elbow like a guardian angel in heels.

“Conversation’s over,” she said. “Any further contact goes through counsel.”

We walked away.

On the courthouse steps, snow was starting to fall. Big, wet flakes that melted on contact with the concrete but stuck in my hair.

Sarah turned to me, hand out.

“Congratulations,” she said. “You just grew a spine in front of a district court judge. Feels good, doesn’t it?”

I laughed. It burst out of me, half-sob, half-hysterical.

“Yeah,” I said. “It kind of does.”

She squeezed my shoulder.

“Go drive your truck,” she said. “You’ve earned it.”

Word got around the local fast.

I got back to the yard that night and found three guys leaning on my F-150, pretending to admire the rims.

“Hey, lawsuit boy,” one of them called. “You done beating up your parents yet?”

“Judge did most of the beating,” I said, tossing my duffel in the back.

By seven o’clock, there were twenty of us. Welders, fitters, helpers, a couple of operators. Somebody showed up with a keg in the back of a beat-up Chevy. Somebody else brought coolers of Coors and a bag of questionable hot dogs.

We caravanned out to an empty field outside Bennett, dirt road running alongside a barbed wire fence, stars so bright it felt like you could step on them.

We built a bonfire out of scrap pallets and old two-by-fours, the flames throwing sparks into the cold sky. Someone backed my truck up close enough to feel the heat on the tailgate.

“Got a hitch ornament for you,” one of the guys said, grinning.

He held up an old washer with a rough, ugly bead welded around the edge. Somebody had written “JORDAN’S TEARS” on it in soapstone.

They hung it from my tow hitch with a length of chain. It swung back and forth, catching the firelight.

We shotgunned beers, passed bottles, told stories about nightmare families and worse bosses. Someone imitated Mom on the stand. Someone else imitated Jordan in Cancun.

“What kind of psycho sues his own kid for a truck?” a helper asked, genuinely baffled.

“The kind who confuses ‘love’ with ‘ownership,’” an older fitter said. “Seen it before.”

At some point, they convinced me to stand in the back of the truck and make a toast.

I climbed up, boots scuffing the bed liner, beer in hand.

“To all the guys who never got a college fund,” I said, voice louder than I expected. “To all the kids who watched their little brothers get new trucks while they took the bus. To everyone who was told, ‘You’re fine, he needs it more.’”

A rumble of agreement.

“And to the moment,” I said, lifting the can, “when you realize you don’t owe them your bones.”

We drank.

Somebody poured a little beer out onto the dirt “for Ethan’s childhood.” I laughed until my stomach hurt.

Around two in the morning, people started peeling off. Work came early. The fire burned down to coals. The stars went on blazing.

By four, it was just me and the truck.

I climbed into the driver’s seat, shut the door, and turned the heat up until my fingers thawed.

My hands found the steering wheel like they were coming home.

For the first time since the day I’d signed the papers, I let myself really feel it.

Not the anger. Not the courtroom adrenaline. Not the satisfaction of winning.

The grief.

Grief for eight-year-old me mowing lawns while Jordan played PlayStation. For fourteen-year-old me smelling like fries while Jordan revved a Mustang. For eighteen-year-old me driving a rattling Civic to North Dakota while Jordan unwrapped keys in the living room.

Grief for the kid who slept in the toolshed some summer nights because Jordan wanted the bigger bedroom and Mom said, “Don’t make a fuss, Ethan. You’re so adaptable. It’s only fair.”

I cried. Ugly, full-body sobs that wracked my shoulders, fogged my windows, made my chest ache.

I cried for the boy who had given his brother the bigger half of every candy bar.

He was gone.

I had buried him the moment Judge Harlland said “unequivocally the property of Ethan Hayes.” The moment I looked my father in the eye and said, “Better than I lived with you.”

When the tears finally stopped, I sat there in the quiet cab, heater humming, the smell of Red Bull and sweat and leather wrapping around me.

Outside, the last embers glowed. The metal washer on my hitch clicked softly in the breeze: Jordan’s tears, tapping rhythm on steel.

Life didn’t turn into a movie after that.

Nobody wrote me a check for my pain. My parents didn’t have a Hallmark epiphany and show up with apologies and pie.

Six months later, my phone rang at 2:17 a.m.

Dad.

I stared at the screen.

I thought about missed calls from him in the past: Jordan in the ER. Grandpa gone. Bills due. Always needing something.

I let it go to voicemail.

Next morning, curiosity won. I listened.

“Your brother totalled your mother’s Suburban,” Dad said. His voice was tight. “DUI. She’s beside herself. We need to get him into another vehicle so he can keep his job prospects open. The bank says he needs a co-signer. Call me back.”

I didn’t.

Mom texted three days later.

Your brother is really struggling. He needs his big brother. Please think about what family means.

I stared at it until the screen went dark.

Then I left her on read.

No reply. No apology. Just silence.

It felt like leaving a sinkhole unpatched and driving around it instead of over it. Safer. Sadder.

The truck kept rolling.

Work took me back to Wyoming, then down to the Permian. Long hauls on I-80 with semis for company. Dirt lease roads that turned to soup when it rained. Rigs that lit up the night like alien towers.

The odometer rolled past 100,000 miles, then 112,000.

The windshield caught a rock from a passing semi outside Rawlins and cracked—a little starburst right in my line of sight. Chip repair guy did what he could. It still caught the sunlight sometimes, a reminder that nothing stays perfect.

I backed into a compressor skid on a cramped location in the dark and put a dent in the tailgate. Swore loud enough the pumper on duty laughed for ten minutes.

Coffee sloshed out of travel mugs and stained the carpet. Detailers tried once. Shook their heads. “Man, this is industrial,” one said.

It smells like burnt coffee, sweat, welding rods, and cheap energy drinks now.

It smells like my life.

Some nights, off tour, I crawl under the truck on my creeper, headlamp on, and just look. Check for leaks. Inspect the exhaust. Touch the frame.

Out in the Permian, you park the truck so the nose faces the flare stack. Lie on the ground, hands behind your head, and watch flame roar a hundred feet into the air, burning off gas nobody thinks is worth keeping.

I lie there and watch it and think about fuel wasted and people wasted and how damn easy it is in this world to believe you’re only as good as what you can supply.

I think about that kid in Aurora who thought if he never asked for anything, his parents would at least leave him his scraps.

He’s dead.

He died in a courtroom in Arapahoe County when a judge said the words malicious and attorney’s fees and looked at Jordan and told him to get a job.

I miss him sometimes. He was soft. He was kind. He believed in things that turned out not to exist.

But I don’t miss being walked on.

I’m Ethan Hayes. Thirty years old. Debt-free. Owner of a 2021 Ford F-150 Lariat with a cracked windshield, a dented tailgate, and more miles than anybody expected it to survive.

I paid for it with skin and sleepless nights and loneliness nobody is ever going to refund. I paid for it with every time I said “sure” when I wanted to say “no,” every time I wire-transferred money south instead of buying myself a pair of boots that didn’t leak.

That truck isn’t just leather and steel and horsepower. It’s a line in the sand.

It’s the moment I stopped letting other people define what I owed.

People ask me now, half-joking, half-curious, “You ever worry your old man’s gonna try something again?”

I look at my keys. At the name on the title. At the scars on my hands.

And I say, “If my own father ever tries to take these keys again, he’s gonna find out I know how to fight back.”

Then I get in my truck, start the engine, feel that familiar rumble under my feet, and drive.

Not away from anything.

Toward the life I built.

THE END

News

THEY KICKED ME OUT OF THE INHERITANCE MEETING—NOT KNOWING I ALREADY OWNED THE ESTATE

Part 1 Some families measure their history in photo albums or keepsake boxes. The Morgan family measured theirs in acres….

Mom Gave My Inheritance To My Brother For His “Dream Life”… Then Learned The Money Had Conditions

PART 1 My mother handed my brother a check for $340,000 on a warm Sunday afternoon in March, at the…

MY FINANCIAL ADVISOR CALLED ME AFTER HOURS AND SAID “DON’T DISCUSS THIS WITH YOUR SON” — WHAT SHE…

If you had asked me, even just a year ago, what the most terrifying sound in my life was, I…

German Pilots Laughed When They First Saw the Me 262 Jet — Then Realized It Was 3 Years Late

PART I January 1945. Snow fell in slow, ghostlike flakes across the Hards Mountains as wind clawed at the wooden…

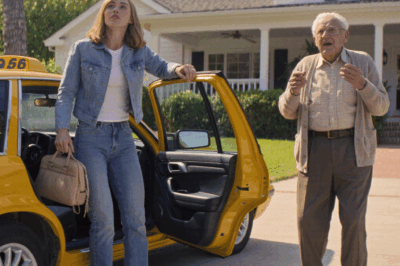

“My Grandpa Asked In Surprise ‘Why Did You Come By Taxi? What Happened To The BMW We Gave You’…”

The taxi hadn’t even pulled away from the curb before my grandfather’s front door swung open like the house itself…

Karen Hid in My Cellar to Spy on Me — Didn’t Know It Was Full of Skunks in Mating Season

PART I There are people in this world who’ll go to ridiculous lengths to stick their nose into your…

End of content

No more pages to load