Part I

The lump started like a bad idea: small, ignorable, something you tell yourself you’ll “deal with later.” I found it at the end of a Tuesday shower, fingers soapy, hair heavy with lavender shampoo. Behind my left ear, at the soft curve where neck met skull, my fingertips landed on a bead-sized bump—P-shaped, as if my body had decided to sprout punctuation. It was tender, not alarmingly so, the kind of tender that says, I’m here, take note, but not yet sound the alarm.

“Harper, can you pass the towel?” my mom called from the hallway, like she always did, where she also always stood with her tablet and a podcast chattering low from its speaker. I stepped out, hair dripping, palming the lump like it might roll away.

“Can you look at this?” I asked, and because old habits are vines, I tilted my head and parted the wet hair with two fingers. She leaned in, squinted—one second, two, then a tired little smile. “Everyone gets swollen lymph nodes sometimes,” she said. “It’s probably a little cyst. Stop reading medical websites.”

The vines tightened around my rib cage, the same way they had when I was sixteen and fainted during biology class, when my mother said it was “sugar crash” even though I hadn’t eaten. When I was eighteen and thought my appendix was rupturing—turned out to be a stomach virus that cost my parents $600 in urgent care bills and weeks of sighs. When I was nineteen and felt the marching-band drumline in my chest for no reason—heart palpitations, then the doctor labeled it anxiety, and my parents laminated the label and pressed it to my forehead.

That Tuesday, my father got home from work and the house recalibrated itself: the slam of his briefcase on the kitchen counter, the refrigerator door yawning open as if in relief, the television thundering to life. He always came home hungry for sound. I stepped into the doorway between the kitchen and the hall, hair braided now, the bump behind my ear suddenly like a secret that wanted out of me.

“Dad?” I said. “I found a—”

He didn’t look up. “How much was the water bill this month?” he asked my mom.

“Dad,” I tried again, and when he finally cut his eyes to mine, I lost that first breath of bravery. “There’s this little lump.”

“How much?” he repeated to my mother, then to me: “You have a phone. Google it. Save us all three hundred dollars.”

“Honey,” my mother said, the podcaster still muttering something about meal prep for working moms. “It’s fine. You get worked up, you Google, it gets bigger in your head.”

“I can’t make it bigger with my brain,” I said. “It’s behind my ear.”

He turned back to the TV and cranked up the volume until laughter swelled and made my ribs rattle. “You want attention,” he said. “You’re twenty years old. Get a job that pays better than a bookstore if you want to collect specialists like Funko Pops.”

I did have a job. I had textbooks and tuition and the quiet, persistent shame that rents a room in your chest when you’re old enough to be an adult but not old enough to afford one. I paid gas and a share of the groceries and “household expenses,” a phrase that always meant more than it said. The lump nestled into these economies like a stray cat—uninvited, persistent, impossible to ignore once it had chosen your porch.

At first, I tried to outmaneuver it. I took ibuprofen before shifts. I pressed hot washcloths to it until the skin pinked and steamed. I texted a friend from community college whose sister was a nursing student, and she texted back a list of “watchful waiting” steps and a bright yellow heart. Watchful waiting, it turned out, was just a neat term for counting days and pretending you aren’t counting.

Then it grew. P-sized became marble. Marble became almond. Almond tried on the word “golf ball” the way middle schoolers try on identities; nothing fit, so it kept changing. On a Thursday morning, I gathered my hair into a ponytail and the base of my skull throbbed in protest like a bruised peach. That’s when I said, “Mom, it’s getting really big.”

She barely glanced up, like her eyeballs were rope-bound to that tablet. “We’ve discussed this,” she said. “You spend too much time on WebMD. It’s probably a cyst.”

“Cysts don’t usually grow this fast,” I said, and because childhood has its reflexes, I added, “Please.”

“You just like to worry,” she said gently. “The doctor told us anxiety can make things feel bigger.” She smiled, as if that was mercy, as if the smile was a balm.

“Mom,” I tried again, and my father’s voice roared from the doorway like a dog lunging off a leash: “Do you know how much that last doctor’s visit cost?”

The last time, eight months ago, I’d gone in for the palpitations. The machine printed out little mountains and valleys, and then the doctor—a man with symmetrical teeth and kind, indifferent eyes—said it looked like anxiety. I cried from relief and shame, both, and paid my portion in tips and overtime shelving returns at the register. After that, every time I mentioned pain or fatigue, my parents’ faces arranged themselves in the geometry of disappointment. Hypochondriac. Drama. Crying wolf. We didn’t use those exact words every time, but they hung from the ceiling like Christmas decorations we never bothered to take down.

“Mom,” I said, quieter now. “I know my body.”

“Your body is fine,” she said. “Your mind is loud.”

By then, my younger sister Megan had learned the art of hallway invisibility. Seventeen and coltish, she took in the scene and then pretended she hadn’t seen it, standing very still until the argument drifted past her like fog and left her untouched.

In the mirror, my neck was beginning to hitch and angle in ways that camera filters couldn’t fix. I started wearing scarves. In July, I wore a hoodie. It turned the lump into an ordinary hill, something you could pretend was a fold of fabric. The heat trapped sweat in my hairline and dampened my neck. At work, my manager Linda leaned over the register while I restocked stickers that said READERS ARE LEADERS.

“Harper, honey,” she said. She was fifty-something and wore her eyeliner like a battle flag. “I don’t mean to pry, but that swelling—have you seen a doctor?”

Tears rose like a weather front I couldn’t outrun. “My parents think I’m being dramatic,” I said. The word was a splinter in my tongue. “I’m on their insurance. Last time I went without telling them, the bill came and—” I trailed off, because anyone who’s ever been somebody’s child knows what comes next is predictable: the fight, the silent treatment, the punishment. In our house, the currency of love was compliance, and I had been overdrawn since I learned to say no.

Linda’s face tightened, eyes sharpening on some point beyond me—an old anger, maybe. She pulled a receipt roll from under the counter and scribbled a name. “Free clinic on Riverside,” she said. “They see people without insurance. Please go.”

I took the paper, folded it, tucked it into my wallet behind my expired library card. The last time I had gone somewhere without telling my parents, when I had the stomach bug appendicitis scare, my father’s anger burned for a week. Anger has a way of reheating, of simmering. After that, he had said—soft, controlled—“You’re manipulating us.”

“She’s got this hypochondria as a manipulation tactic,” my mother had said, like she had learned a new word and wanted to use it in a sentence.

You learn to make yourself small in houses like ours. You learn to love quietly so no one thinks you’re asking for more. You learn to be grateful for what you’re given even if it’s just a folded receipt with an address you won’t use.

Weeks passed. The lump grew until it introduced itself before I did. Customers glanced and away again, faces rearranging themselves into the practiced neutrality of polite strangers: I saw nothing, I will not ask. Pain hummed in a low, steady chord. It radiated down my neck and into my shoulder, into the hinge of my jaw, grinding the back of my left eye like a gear in need of oil. Some days, the pain was a jackhammer. Other days, it was a metronome. I could work around a metronome.

At night, I lay on my right side because the left triggered throbbing. I stopped sleeping on my back; the pressure there made my thoughts turn to kettlebells and weights, things that swing and drop and crush. I learned the choreography of sick people who aren’t allowed to be sick: how to smile in ways that don’t use certain facial muscles, how to nod without moving your neck, how to shift your hair to hide a new war wound.

My father found me crying silently at the dinner table one night when I couldn’t disguise the drilling behind my eye. “This is getting ridiculous,” he said, so reasonable, so calm that it sounded like love. “The theatrical groaning, the dramatic whatever. We get it, Harper. You want attention.”

“I want help,” I said. “Please. Let me see a doctor. I’ll pay you back. I promise.”

“With what money?” He tapped his fork against his plate. Tap, tap. “You can barely hold a job because you’re always sick.” He pulled the word sick up with his fingers as if it were a puppet. “You’re trying to get out of responsibilities.”

My mother nodded, relief pooling between her eyebrows like a released breath. “Remember when you were convinced you had appendicitis?” she asked, smiling like a good story was warming up. “Six hundred dollars for a stomachache. Or the meningitis scare? That was the funniest—just a tension headache.”

“Menitis,” my father parroted from across the table, and the word fumbled itself into a joke that tasted like metal in my mouth.

Those were real symptoms, I wanted to say, but my father slapped his palm against the table, plates jumping. “I’ve made an appointment for you with a psychiatrist,” he said, “because the only thing wrong with you is in your head.”

I swallowed my arguments like vitamins: big, chalky, stuck in my throat. When I spoke, my words came out covered in that chalk dust. “Okay,” I said. “Fine.” Because I had already learned this: compliance might not earn mercy, but resistance will always earn war.

Dr. Brennan’s office smelled like new carpet and stale coffee. He was a friend of my father’s; I knew this because my father said “Bren” in the car and because pictures of golf clubs in the half-light of evening hung in frames on every wall. In the session, Dr. Brennan made his mouth into a sympathetic shape as if pinching a penny between his lips. “Your father mentioned you’ve been fixated on an alleged growth,” he said kindly, accenting alleged in a way that turned my stomach into an empty room.

“It’s not alleged,” I said. “It’s real. It hurts.” I tugged my hair back to show him. He looked just long enough to get the idea, then nodded as if checking a box. “I’m not a medical doctor,” he said brightly, “but that looks like a simple lipoma. Harmless. Your preoccupation with it, however, is concerning.”

His prescription pad scraped across the desk twice: once for an anti-anxiety medication, once for cognitive behavioral therapy sessions he offered at a discounted rate because we were friends of the family. When I got home, my parents looked relieved enough to stop looking at me. My father kissed my mother’s forehead. “We’re getting her help,” he said.

The lump pulsed. It swelled under my skin like a hot fist. I started to hear my heartbeat in it while I shelved books, while I brushed my teeth, while I counted quarters and nickels for the bus. By month five, my hearing in that ear muffled. Sounds came through a towel. I learned to lip-read Linda when the store got loud.

Then the episodes started. The world tilted forty-five degrees, then ninety, like a floor breaking loose. My vision blurred at the edges. I clutched the counter, smiling whenever a customer blinked at me. “Just dizzy,” I’d say, as if dizziness was a charming hobby.

“You’re taking your anxiety meds, right?” my mother asked. “Dr. Brennan said it might take time.” I swallowed the pills every night and every morning, and my heartbeat still drummed in my ear like someone building a deck on the side of my skull.

Six months after that Tuesday shower, I woke to a pillow soured by a smell I knew and couldn’t place and then remembered: infection. I touched my hairline. My fingers came away wet. The lump had opened. It was draining something viscous and foul and undeniable.

I showed my parents. My father handed me hydrogen peroxide like he was flinging a life preserver to someone drowning in a kiddie pool. “Clean it,” he said. “Stop being dramatic. It’s probably an infected pimple finally bursting.”

“An infected pimple the size of a tennis ball,” I said. But even then, I took the brown bottle and the cotton swabs and went to the bathroom, because you acclimate to madness one small obedience at a time.

At work that afternoon, I climbed a two-step stool to reach a display of hardcover novels about why the world ends. The vertigo wasn’t a tilt this time. It was a whirlpool. I felt my legs give and the air change pressure and then the hardcover books looked like a flock of startled birds. I fell.

What came next belonged to other people. The seizure took my body away and made it a whale thrashing in a small pool. Foam filled my mouth. Linda’s voice sliced through the chaos, too sharp to be mine: “Call 911!” I remember how blue the sky was through the store’s front windows and how the bell above the door kept ringing as people ran.

When I woke up, a hospital ceiling poured fluorescent light over me. A doctor whose face I didn’t know watched a computer screen full of my insides. He turned when I made that small, animal sound people make when life returns to them.

“Miss Thompson,” he said, “I’m Dr. Patel.” His voice was the steady, practiced voice of people who carry others over rickety bridges. “How are you feeling?”

“Confused,” I said. “What happened?”

“You had a grand mal seizure,” he said. “Your manager said you collapsed at work.” He looked at the computer again and pursed his lips as if deciding to use a word that meant more than it sounded like. “Harper, when did you first notice the mass behind your ear?”

“Six months ago,” I whispered, the number gaudy in its awfulness. “My parents said I was being dramatic.”

His jaw shifted, a reflex of anger put back into its holster. “I see,” he said carefully. “We’ve run tests—MRI, CT, blood work. I need to be direct with you.” He stepped closer, and I could smell hand sanitizer and something citrus. “The mass is not benign. It’s a rare form of cancer called chordoma. It’s been growing along the base of your skull and is now pressing against your brain.”

For a second, the word was just sound. Chordoma. It clinked like a coin dropped on a table. Then it burst open and my body understood. I felt the sinking boat. I felt the cold water. And then, weirdly, I felt this filament of relief. It had a name. It wasn’t drama. It wasn’t hypochondria. It wasn’t the complicated landscape of my mind.

“How bad?” I asked, and it came out like a stranger talking through my mouth.

“It’s advanced,” he said gently. “Six months ago, this would have been a relatively straightforward surgery.” He pulled up the scans. On the screen, my skull was a pale moon, and something dark had been scrawled across its horizon by a toddler with a thick marker. “Now it’s invaded surrounding tissue, wrapped around critical nerves, extended into your cranial cavity.” He looked at me. “We need to operate immediately, but it’s going to be complicated.”

“My parents,” I said, reflex betraying me even then. He lifted a hand.

“They’ve been notified,” he said. “They’re in the waiting room with someone they identify as their lawyer.” His mouth did a thing like he had stepped on a nail and didn’t want to say it hurt.

On the TV in the corner, a muted cooking show showed a woman cracking an egg. The yolk broke cleanly. I had the disorienting thought that whoever she was, wherever she lived, she had no idea I existed or that my brain was under siege, and the thought comforted me. We are all so small. We are all so miraculous. We can be both at once and still be loved.

“Okay,” I said. “Okay.”

Out in the waiting room, the world was wearing its good clothes. Inside me, something was tearing down walls with both hands.

Part II

They took my earrings out. They shaved half my head. A nurse named Kelley drew little dot tattoos behind my ear to mark landmarks for radiation, though we hadn’t yet gotten to radiation, hadn’t yet even reached surgery. Everything felt like a step in a choreography my body had learned overnight: IV drip, oxygen sensor, consent form, soft-voiced explanations of risks that clanged like pans in the back of a restaurant.

Before they wheeled me in, Dr. Patel sat. He sat on the little stool with wheels that doctors always sit on when they want to look less like gods and more like people. “Is there anyone you want me to call?” he asked.

“My manager,” I said, surprising myself. “Linda.”

He nodded, jotted it down, then asked, “Your parents will sign your forms?”

He already knew the answer to that; he had seen their lawyer. I nodded anyway. I was twenty. I was an adult. But the insurance card that paid for the MRI had my father’s name in bold letters. There is an absurdity in the American way of being sick when you are young and poor and someone else’s dependent: that your body belongs to you in principle and to your parents’ premiums in practice.

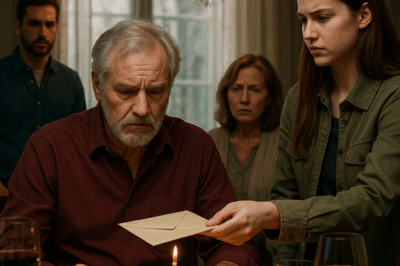

They wheeled me past the waiting room. My parents and a thin man in a thicker suit sat on vinyl chairs designed to make staying feel like a bad idea. My mother’s mascara had surrendered. My father turned a shade of white that looked glamorous on kitchen cabinets but alarming on faces.

“Harper,” my mother said, rising with arms out like misfired kindness. “We only wanted—”

Their lawyer reached out a hand—small, polite—parting the air as if brushing cobwebs from a doorway. “We should wait,” he murmured in my father’s ear. “Let’s wait.” It was reflexive, and I felt it even in the anesthetic fog: he saw a problem, he applied barbed wire.

Dr. Patel nodded at them. He did not soften. “We’re moving quickly,” he said. He held out the clipboard. “Consent.”

My father took the pen as if it were a live snake. “What exactly are you doing?” he asked, the edge slipping back into his voice like an old friend.

“Removing a skull-base chordoma,” Dr. Patel said. “We’ll approach from the mastoid region, with possible transpetrosal access if we need it. We’re coordinating with ENT for cranial nerve monitoring. It’s complicated and time-sensitive.”

“You’re telling me my daughter has—a rare brain tumor?” my father demanded. “Are we certain? Because—”

Dr. Patel’s eyes cut to mine, then back. “We are certain,” he said. “Waiting is not an option.”

For a second, something in my father flickered. The world he had built—the one where bravery looked like ignoring pain, where money was the only honest metric—had a crack in its wall, and he could see blue sky through it. He didn’t know whether to fix it or walk through. He shoved the pen into the paper. He signed. He handed it back like it had burned him.

When they rolled me away, my mother’s knuckles were teeth-white around her purse straps. “We love you,” she whispered into the place the air used to be between us. I believed her. I did. I believed that she loved me inside the perimeter of the life she had drawn around herself, and I believed that the life had smaller doors than she knew.

Surgery is a story other people tell you about yourself. You go for a ride into sleep and return to find that someone has moved furniture inside your skull. I only know the details because Dr. Patel told me later in neat, unadorned language and because when I close my eyes, I can picture him talking, not the room where I lay unconscious while a team sketched battle lines along my bones.

Fourteen hours. “We got most of it,” he said afterward, through a mouth that looked like it had carried a piano up a flight of stairs. “It’s been growing for at least a year, possibly longer. Multiple growth phases.”

“Which is—?” I asked, voice a ragged thing scraping against the edges of my throat.

“Evidence that there were windows of intervention,” he said gently. “It’s wrapped around critical nerves. We knew that. We preserved what we could. You’ve lost most hearing in your left ear.”

The words landed and sank, soft as stones. He said, “When you’re stronger, we’ll talk radiation. Maybe proton beam if we can get approval.” He said, “I documented everything.” He said, “I’m sorry,” and in his mouth the word wasn’t pity or habit. It was a small altar.

“Linda?” I asked, because love is a compass you keep checking to make sure you didn’t stray too far from the map.

“She’s here,” he said, smiling softly. “She’s been here.”

My parents had not. They tried once, the nurse told me later. They came in with the lawyer in tow and stood at the threshold as if the room were a cliff edge. They looked at my shaved scalp and the clear tubing and the little square of tape on my chest. My mother cried. My father cleared his throat twice and said, “We only wanted what was—.” The lawyer put a hand on his elbow and they left. A hospital corridor is a long place when you’re trying to outrun your choices.

Recovery taught me the schedules the body keeps. Pain had an appetite and a bedtime and bad table manners. Nausea was an unreliable houseguest. Dizzy spells arrived uninvited but insisted that they knew me. My face was a map of the nerves that had been bruised and stretched and moved around. When I yawned, a little muscle behind my jaw did a pop-and-hiss like a soda tab. When I laughed—which happened when Linda came because she told stories like she was pouring warm coffee—I had to hold my head to keep it from feeling like a guitar string pulled too tight.

“The bookstore has never been so tidy,” she said one day, perched in a rigid visitor chair with a Tupperware of something that smelled like real food. “Turns out if the chaos pixie who runs the fiction display is out, we all discover the Dewey Decimal call numbers again.”

“I’ll write an apology to the chaos,” I said, and she grinned.

“I brought lasagna,” she said, shoving the container toward me like a love letter. “Don’t tell your nurse or I’ll have to smuggle it under my shirt next time.”

We ate in tiny squares because my mouth didn’t believe in the mechanics of chewing anymore. We talked about the store, and then about books we’d each pretended to like and actually hated, and then about my case. I used to call them “my case” because I needed the legal language like armor. It made it less about my body, more about a problem to be solved.

“They talked to me,” she said. “The hospital. I told them you’d been asking for help for months. That you were scared. That you were always trying to make it easier for other people.” She blinked. “I told them I should’ve driven you to the clinic and adopted you on the way.”

“You tried,” I said. “You did more than anyone else.”

“I folded a receipt,” she said. “Not exactly heroism.”

“We don’t get to pick our props,” I said. “Sometimes it’s an oxygen mask. Sometimes it’s a receipt.”

A week later, Dr. Patel came in with a folder. I braced myself in the way you do—breath shallow, expectations small, a hand around the neck of the beast you know might leap. He sat again, palms flattening the air as if smoothing a sheet. “Pathology report,” he said. “It confirms chordoma.” He tapped a page. “There’s necrotic tissue here where the tumor outgrew its blood supply. There’s evidence of multi-phase growth. And there are—and this part is complicated—genetic markers that indicate the tumor was likely triggered by chronic inflammation. The kind you’d see in cases with repeated, untreated infections.”

He watched me as if I might break. “You mentioned previous episodes,” he said. “Appendicitis scare. Headaches. Fevers. We retrieved your records.” He took a breath. “You weren’t wrong. You had clear signs of systemic infections. They were dismissed. Your body was trying to tell you something. The untreated inflammation likely contributed to the tumor’s growth.”

People talk about gut punches like anger. This felt like the opposite. It was a deflating, a surrender. I thought about the hydrogen peroxide and the “stop googling” and the way my father’s lips formed “six hundred dollars” like a curse. I thought about being told to make my mind quieter when my cells were screaming.

“I tried,” I said. It came out small.

“I know,” he said. “That’s why I’m documenting everything.” He tapped the folder again. “Not to point fingers for the sake of punishment, but because your care was compromised by more than a tumor. We’re seeing you, fully.”

Linda stepped in through the door as if summoned by the right kind of sentence. “I brought smuggled soup,” she announced, then saw the folder and sat down, the humor draining from her face. She reached out. I let her take my hand.

My parents’ lawyer called the hospital at some point while I was still swallowing my breath and said the words consent and liability so many times the syllables lost meaning. An administrator came to talk to me about bills and coverage and then quietly asked if I wanted a social worker. This is how kindness looks in the ledger of a hospital: an offer, an appointment on somebody’s calendar, a silence in which you can decide that you are worthy of assistance.

I said yes. The social worker, a woman named Riya with soft eyes and a pen that clicked like a metronome, came and taught me words I would later memorize for a courtroom. Medical neglect. Insurance coercion. Dependent adult. She asked, “Do you have someone who can be your advocate?”

“Linda,” I said without thinking.

Linda looked startled and then not. “Yes,” she said, like she was picking up a bag she had been carrying in a previous life. “Whatever you need.”

The surgery bill arrived like a small, vicious novella: too many zeroes, too much plot, not enough character development. The social worker helped me apply for hospital assistance and a payment plan that felt like it would last into my forties. Riya also told me what I already knew in the coarsest language: my parents had controlled access to care by dangling the insurance card and slapping my fingers whenever I reached.

“You’re twenty,” she said. “You’re allowed to make your own medical decisions. But the financial abuse—”

“Abuse?” I repeated, the word both too big and exactly right.

“Abuse,” she said again. “We don’t use it lightly.”

I held the word like I would hold a rare egg—careful, awed, terrified that I’d drop it and ruin the proof.

Megan came one evening carrying a ziplock of starburst and a stiffness that made me want to take a step back and a step forward at the same time. She was suddenly eighteen: adulthood had arrived on papers and in her eyes. She looked at my head like it was a baby bird. “I’m sorry,” she said, and then put a hand over her mouth like she’d spoken too loud.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You didn’t do this.”

“I knew something was wrong,” she said in a rush. “I could see it growing. I should’ve said something. I should’ve—.” She stopped like a car at a broken light, unsure who needed to go first.

“You were a kid,” I said. “You saw what happened when I said anything.”

She bit her lip, then pulled out her phone. “I started recording,” she said, hesitant. “After you collapsed. Dad yelling about the doctor bills. Mom saying you were faking. I thought—maybe someday it would matter.”

I looked at her. At the screen. At my sister, who had learned to be invisible and was now choosing to be a witness. “It matters,” I said.

The next week, a lawyer with soft shoes and hard questions came to my room. “You don’t have to sue your parents,” he said, voice even, careful. “I’m not suggesting a courtroom and a headline. But you have rights. You need help with medical bills. There are settlement agreements. There are ways to make them accountable without dragging you through hell.”

“I don’t want revenge,” I said. “I want to breathe without measuring how much air costs.”

“That’s a start,” he said.

When I thought of suing, I thought of Christmases and birthday candles and a father who taught me to parallel park by smacking the dashboard every time I almost bumped an imaginary car. I thought of my mother’s hands making pie crusts and smoothing the bedspread on Saturday mornings, of the way she hummed to the radio when she cleaned, of the first time I bled and she sat with me, a soldier in a small war I could not name yet. Love has receipts, too, and they are crumpled and stained and faded, tucked behind the expired library cards.

But I also thought of the lump the size of a baseball, of hydrogen peroxide, of my father’s mouth curling around the word manipulation as if it were both theory and fact. I thought of how much power a person has when they hold the keys to both the car and your access to a doctor you can’t pay for without them. I thought of the word Riya had given me and how it had felt both heavy and right in my hand.

The day before I was discharged, Dr. Patel came in and sat and told me about my post-op plan like a teacher walking me through a syllabus. I had re-entry homework: watch for fevers, for certain kinds of pain, for certain kinds of numbness. There would be radiation. There might be chemotherapy. There would be scans forever. He also told me something else—something that felt less like a lab value and more like a vow.

“There is something else you should know,” he said. “Your case—it’s going to change how I practice. When young people come in with concerns their parents dismiss, I will look closer. I will listen harder.”

I felt the flutter of something under my ribs that might have been gratitude or might have been grief. “That’s all I wanted,” I said. “For someone to look.”

He nodded. “I’m sorry it took this.”

“Me too,” I said. “But if it changes the next kid’s story—”

“It will,” he said. He didn’t say I promise. He didn’t need to. He was not a man who spent his promises casually.

The nurse wheeled me to the curb the day I left, hospital bag in my lap like a white flag. Linda’s little blue car idled at the pickup lane, hood streaked with dust. She had taped a hand-lettered sign to the dashboard that said, VIP PICKUP with a badly drawn crown. I laughed, then winced, then laughed again because even pain knew when it had to let a better feeling through.

“We have a couch bed and a noisy cat,” she said as she helped me climb in slow motion. “I already told them both to be gentle with you.”

“You don’t have to—” I started.

“I know,” she said. “But I want to.”

On the drive to her small apartment, the world looked excessively alive. The sky was sky-blue in a way weather reporters never capture. The trees were flamboyant. People’s mouths were open in laughter. I watched a man in a fluorescent vest lift a stop sign so children could cross a street and thought: We are all getting each other across in these small ways.

In Linda’s guest room, which was also an office and a craft room and a place where lost buttons came to be sorted, I lay down with a cat whose tail was a question mark. Linda ran the dishwasher. The cadence of home wrapped itself around me gently. I fell asleep to the small, ordinary noises that mean safety: a neighbor’s bass bleeding through a wall, a car door slamming, an ice maker in the fridge coughing out cubes.

When I woke, I checked the place where my ear had been my enemy. The swelling was different—cleaner, colder, a geography I could learn. The world had been busy while I slept. A new map had been drawn. The old one still bled through in places—places that would take years to fully erase—but I could follow this one. I could still get where I needed to go.

Part III

Radiation made me taste metal. It made the skin on my neck feel sunburned from the inside, and it taught me that exhaustion can be an animal that climbs on your chest and refuses to get off. The techs put on playlists that had been carefully, probably scientifically curated to make patients feel less like science projects. One day it was Motown and I cried because all that joy had been recorded by people who made something perfect in a world determined to make them small. Another day, it was soft rock from the nineties and I laughed because I couldn’t picture any context in which those songs belonged, except this one: holding still under a machine that sounded like the gears of a building grinding together.

Linda drove me when she could. When she couldn’t, I took ride shares whose drivers made small talk and pretended not to notice the hair growing back at uneven altitudes on my scalp. Megan took a bus one Saturday and showed up at Linda’s with a bag of strawberries and a new voice. She had found it somewhere between seventeen and eighteen, between being someone’s daughter and being her own person.

“They’re selling the house,” she said, by way of hello after a long hug in the doorway. “Or they might. There’s talk.”

“I’m sorry,” I said automatically. But I wasn’t. Or rather, I was sympathetic for the shock, not the consequence. Our house had been four bedrooms and a yard and a mortgage that my parents wore like armor. If they were selling, it wasn’t the market’s fault. Megan sat down at Linda’s little table and pulled out her phone, and morality suddenly had receipts again.

“Listen,” she said, thumbing through a folder labeled with the plainest name in the world: Recordings. She hit play. My father’s voice poured out, familiar and foreign. “This is manipulation,” he was saying. “She’s doing this to get out of responsibilities.” My mother’s voice followed: “We won’t enable this. She’s faking.”

I had lived with those sentences. I had tried to write songs around them, to rearrange them into something less like a weapon and more like a prop. But hearing them now—their certainty, their total dismissal—I felt a solidifying. It wasn’t anger exactly; anger is hot. This was cold. A planet taking on mass and shape and atmosphere. A name. Evidence.

“Megan,” I said. “This is—”

“I know,” she said, suddenly timid again now that the brave part was over. “I thought maybe your lawyer could use them.”

The lawyer did. We met with him at a mid-price office park where the carpet was new and the people in the elevator smelled like toner and ambition. He was direct and decent, which is, I learned, a more useful combination than brilliant and oily. He explained the options and never once used the word revenge. He talked about consequences like weather: predictable, unstoppable, not personal but impactful.

“The hospital cooperation helps,” he said. “Dr. Patel’s documentation helps. The recorded statements help. We’ll propose a settlement. We can do this quietly, if that’s your preference.”

“What does quiet mean?” I asked.

“No press,” he said. “No public filings with hand-wavy accusations. We submit the evidence to their counsel, we outline damages and a demand, and we schedule mediation. If they’re smart, they’ll settle. If they’re not—” He lifted a shoulder. “We go to court. But I’d bet my lunch money they’ll settle.”

I stared at the legal pad on his desk, at his tidy squares of handwriting. I thought of my mother’s hands rubbing lotion into her knuckles at night, a small ritual of care for herself I had often mistaken as selfishness. I thought of the way my father had breathed hard through the words “six hundred dollars.” Money had been his god, his ghost, his shame. If the god came for a tithe now, maybe he’d learn to worship something else.

“I don’t want to ruin them,” I said. It felt important to say it aloud, to make it something I could reach for later. “I want my medical bills paid. I want them to say, We were wrong. I want them not to do this to Megan or themselves ever again.”

The lawyer nodded slowly. “Sometimes the only apology people can hear is one written in numbers.”

He sent the letter. He included the pathology report’s delicate outline of neglect, the recordings Megan had captured like butterflies in a jar, the ledger of bills and projected costs and my lifetimes of follow-up imaging. He did not call my parents monsters. He did not call them anything. He kept the case a case, disciplined and calm, even when I felt like the air around it was a thunderstorm that might split a tree.

Their lawyer was not the man from the waiting room. He had bowed out after a look at the evidence—professional courtesy, or perhaps self-preservation. The new counsel called my lawyer with propositions dressed as pity. “They’re heartbroken,” he said, according to my lawyer. “They feel betrayed. They insist they were acting in Harper’s best interest. They argue that Dr. Brennan was consulted.”

“Dr. Brennan is not a medical doctor,” my lawyer said. “He glanced at a tumor and called it harmless.”

“A lipoma,” the other man recited. “He thought it looked like a lipoma.”

“We have a pathology report,” my lawyer said. “We have a neurosurgeon’s scan showing the tumor’s invasion of the cranial cavity.”

“Is there room for compromise?” the man asked, and my lawyer exhaled softly. “We’re proposing compromise,” he answered. “We’re not asking for punitive damages. We are asking for costs of surgery, radiation, anticipated chemo, lost wages, and a sum to cover lifelong monitoring.”

“Why should they be responsible for lifelong monitoring?” the man asked, and my lawyer took a beat. “Because the monitoring exists due to the progression that occurred while access to care was denied,” he said. He was calm. He was iron. He was everything I needed him to be because I could not be it.

Megan came with me to a mediation session in a room whose walls whispered Like We’re Judges But Less Stressful. My parents sat on one side. I sat on the other with Megan and the lawyer. The mediator, a woman with arched eyebrows and a voice like a yoga teacher, opened with a speech about empathy and common ground. She used words like restorative and understanding. My father crossed his arms. My mother dabbed at her nose with something that was more a ribbon than a tissue; it was so skinny it seemed a prop for someone performing grief.

“Harper,” the mediator said, “would you like to speak about how you’ve been affected?”

I kept my voice low so I couldn’t hear it shake. “I was sick,” I said. “I asked for help. I was denied help. I was told I was making it up. I had a seizure on a bookstore floor. I lost my hearing in one ear.”

My father cut in before the mediator could adjust our lane. “You think this was easy for us?” he said. His voice had always been good at commanding rooms. He wore it like a tailored suit. “We were trying to teach you responsibility. We were trying to get you to stop running to doctors for every twitch and tick.”

“We didn’t know,” my mother said, and the sentence had a ragged edge that might have been honesty. “We didn’t know it was cancer. Who thinks cancer for a lump?”

“I did,” I said, then immediately: “No. I didn’t. I thought it was something serious. I thought I had a right to find out.”

“You had a right,” Megan said, surprising us all with the clean blade of her voice. She had never used it on our parents in public. “You had a right to care. You had insurance that was used to punish you. I heard you,” she said to our father. “I recorded you. You said she was faking. You said she was manipulating you.”

My father looked for an exit. None presented itself. “So you were spying,” he said, and I made a sound somewhere between a laugh and a cough.

“I was alive,” Megan said. “We do what we can to stay alive.”

The mediator steered us back to numbers. The numbers added up to a life: surgery, 200,000; radiation, 80,000; expected scans for five years, 25,000; expected scans beyond that, uncertain. Pain and suffering got a line, but it always looks silly on paper—like trying to tally what a song is worth by counting its notes.

In the end, their lawyer slid a signed document across the shiny table. The settlement didn’t make me rich. It made me able to breathe without hearing the cash register ring. It made it possible for me to plan for follow-ups without needing to sell hours of my life to debt collectors. It meant my parents sold our house. It meant my father’s pride bled in public and my mother’s whisper campaign in her circle failed because the pathologist wrote in unambiguous paragraphs.

After, we stood on opposite sides of a parking lot that looked like every other parking lot in the world: sage green planter boxes, a cigarette butt near the curb, a child riding a scooter. My father said, “We only wanted what was best.” The words were a tired couch, all the springs poking out. “You have to understand, you cried wolf.”

“I never cried wolf,” I said, not raising my voice. “I cried help.”

Their lawyer tugged at his tie. “We should go,” he murmured.

“Get well,” my father said, a parody of a hallmark card. My mother, quieter: “We didn’t know how to be any different.” Then they left.

There was a part of me that wanted them to turn around. To say We were wrong. We are trying to be better. But people don’t become better because you want them to. They become better because something cracks them open and they let the light in. My parents had been cracked. Whether they would let in the light was not, finally, my job.

With the settlement, I moved out of Linda’s and into a studio with a scratched wood floor and a radiator that clicked like a beatbox in winter. I kept working at the bookstore, though Linda tried to promote me immediately because she’s the sort of person who thinks you heal best when you’re trusted with more. I told her I wanted an ordinary register and an occasionally collapsing display of travel guides. She nodded, patient with my need to learn I could do ordinary again.

I enrolled in fewer classes, by design. Community college had been a stage I shared with my tumor for too long. I took a writing workshop because words had saved me more times than I could count—because the last six months felt like a story that had been told about me and I wanted to retell it in my own voice. The professor, a man who wore flannel year-round and read aloud like he was telling ghost stories around a fire, told me to stop apologizing on the page. “Your life doesn’t need disclaimers,” he said. “Your sentences will be enough.”

On Tuesdays, after radiation, I sat in a small room with other young adults whose health had untethered from their expectations. There was a girl whose autoimmune disorder had set fire to her joints. There was a guy whose heart had decided to play jazz at random intervals. We talked about bodies and money and the ridiculous ways people try to comfort you. We laughed a lot. Sometimes we cried. It felt like religion without the hierarchy: the church of the lived body.

I also met with Dr. Patel every month, then every three. He wore the same quiet competence each time. He would lean over the screen and narrate my insides like a tour guide: “Here’s the resection cavity. Here’s the area we’re watching. Here’s what looks stable.” I learned the shapes of my future in grayscale. I learned to say stable with reverence.

In my spare hours, when I wasn’t working or being scanned, I started volunteering at a youth health advocacy center downtown, a storefront with a mural of a girl in a red beanie reading a book while rockets lifted over her shoulder. The director, a woman named Tasha who could write grants like sonnets, taught me how to sit with kids when their parents were driving the car too fast in the wrong direction. We called insurance companies. We translated doctor-speak. We put names to sensations. We said, “You’re not crazy.” We said, “Your body belongs to you, regardless of who pays the premiums.”

Sometimes I told my story. Not the gory parts—the smelly pillowcase, the taste of metal, the half-head shaved like a dare. Those details can be prurient; they can make people listen for the wrong reasons. I told instead about the receipt with “free clinic” scrawled on it. About the folded insurance card that had functioned like a leash. About a sister who turned her phone into a tool and a manager who turned her concern into a ride home. About a doctor who said I’m sorry and meant I will do better. About the way the word abuse had fit in my mouth and become mine.

“You’d be surprised how often people need someone to use that word first,” Tasha said once after a long day. “We think we’re making it dramatic by naming it. But naming it makes it real and small enough to hold.”

“Small enough to hold,” I repeated, and thought of the first day I’d touched the lump, how tiny it had been, how easy it had seemed to ignore.

The news did not always stay good. There were nights I woke with a pain that felt like a remembered song: familiar, unwelcome. There were afternoons when I put a glass down and missed the table by an inch because my brain forgot to tell my hand about space correctly. There were conversations where people’s mouths moved and I didn’t catch enough words to fill the silences. I learned to say, “I’m deaf on that side,” without a preface, without a laugh, without making it easy for someone else. I learned to advocate like I was my own big sister.

One day, months into this new normal, a girl walked into the center wearing a hoodie with the drawstring pulled so tight around her face that only a crescent of skin showed. She was seventeen. Her mother had told her that cramps were “weakness.” Her father had told her that periods were “gross” and “made-up.” She had been bleeding for three months. She had kept going to school. She had kept working in a nail salon after classes. She had begun to tell herself that she was imagining the dizziness.

We sat together in the little office that Tasha had painted a pale color called, with marketing audacity, “Serenity.” I asked questions. I took notes. I heard my younger self in her voice. After, I made calls. The clinic got her in that day. The doctor frowned and wrote orders and then said polycystic and anemia and treatment. The relief on the girl’s face broke something and built something at the same time. “I feel crazy,” she said, and I shook my head. “You feel gaslit,” I said. “That’s different.”

She tilted her head, a movement I understood both for what it meant and how it felt. “Thank you,” she said. “For believing me.”

“That’s all I wanted once,” I said. It came out bitter and sweet, the way truth often does.

Part IV

The thing that stunned everyone wasn’t the diagnosis anymore. By the time the case made its quiet way through the hospital’s corridors and into the coffee mugs of residents, chordoma had become a banner word, a story that other doctors would tell themselves at two in the morning when they needed to be reminded that work matters. What stunned them, in the way a cold ocean stuns you into breathing, was the elegance of the time line: the neatness with which neglect had done its work.

Dr. Patel never said elegant. He said damning. He said clear. He said, “We can point to this month and this month and this month and see the progression. If we had caught it when you first noticed symptoms—well.” He didn’t say we would have saved your hearing, maybe. He didn’t say we would have shaved an inch, not a hemisphere. He didn’t say you would have had a scar so small you could hide it behind hair without learning that hair is more than vanity; it is refuge.

He presented the case at a grand rounds with the kind of measured anger I had begun to recognize in him: the kind that doesn’t turn blame into a blunt instrument but keeps it sharp enough to cut the right thing. He showed the scans. He outlined the standard of care for a young adult with a palpable mass near the mastoid. He referenced the psychiatric referral in the family file with gentleness that made other doctors in other rooms lean forward and remember. He did not use my name, but he had my permission to use my story, because what else is pain for if not to become caution and kindness for someone else?

He wrote a paper, too—not a memoir disguised as a case report but a real paper with citations and conclusions and the kind of neutral tone that feels, to those of us who live in bodies, like an insult and a balm. He included the detail about genetic markers and chronic inflammation. He wrote, “The risk factors include repeated, untreated infections,” and in the margin of the copy he gave me, he circled the sentence and wrote, “Not your fault” in tiny, spiky letters.

The hospital used my case to tweak a protocol in triage for young patients presenting with parent-dismissed concerns. Nurses got cards with scripts: phrases to help them go around gatekeepers without burning bridges. “Can I speak with the patient alone for part of this visit?” “I’m going to order imaging so we can rule out anything serious.” “You deserve to understand your options.” It was small, bureaucratic, but I saw the ripple. I saw a girl in a purple scrunchie at the clinic nod when the nurse used the script and I knew a tiny hinge had turned.

I went to see Dr. Brennan once—not for care, but for closure. It was a bad idea. It was also necessary. He had a new fish in the office tank. The photos of foursomes on the golf course had been rearranged to make room for a framed article about the mind-body connection. He looked older than I remembered, which is a trick memory plays to make you believe you outran something you should have confronted sooner.

“Harper,” he said, warm as toast. “How are your anxiety symptoms?”

“I had a brain tumor,” I said. He flinched. “A skull-base chordoma. It was removed. Mostly. I lost hearing. I have a scar.” I took a breath. I didn’t know until that moment whether I was coming to demand an apology. I wasn’t. I had, to my surprise, an invitation instead.

“You are not a medical doctor,” I said, echoing his sentence back to him like a small, dangerous gift. “But you looked at my tumor and called it harmless. You called my attention to it a problem. You added weight to a scale my parents were already leaning on.”

He looked chastened. Then clever. Then both. “Your father is—” He stopped. He realized, perhaps for the first time in his career, that describing one patient’s father to another patient as a personality type might be problematic. He tried again. “I regret dismissing your concern,” he said. His voice, to my surprise, sounded like it meant it. “In my field, we see health anxiety often. We do harm when we paint everyone with the same brush.”

I made a face. It was not gracious. I have only so much grace to rent out. “Please don’t call this a learning opportunity in a way that makes it my job to be grateful.”

He spread his hands. A white flag, maybe. “Noted,” he said. “It won’t happen again.”

“That’s the only thing I wanted to hear,” I said. I left the office feeling nothing like triumph and a lot like the first breath after you surface from the deep end of a pool. You’re not racing. You’re not even swimming. You’re just breathing, and it turns out that’s enough for a minute.

At the bookstore, people had started to recognize me. Small town, big story. Not because there was a headline, but because you can hide a shaved head for only so long and because a community college writing workshop yields stories that travel farther than the classroom. A woman buying a cookbook for her niece leaned over the counter and whispered, “I told my doctor about the lump on my neck after I read your essay in the campus paper.” A man in a mechanic’s shirt tapped the side of his head. “My sister,” he said. “She thought she was imagining it. She’s getting a scan.”

I learned to accept this without letting it make me into a symbol. I am not your cautionary tale, I wanted to say, and I am also not your saint. I am a person who got sick and got dismissed and got lucky and got bills and got louder. Those are not virtues. Those are events.

Megan started at the community college in the fall. She refused any help from my settlement for tuition and worked weekends at a salon that didn’t ask her to breathe chemical clouds for ten hours. She came over on Sundays for lasagna or soup because Linda had become a person we both gravitated toward instinctively, like moss to the damp side of a log. We watched shows that required no emotional investment. We played a card game with rules so easy it felt like we were being conned. We laughed. Sometimes we cried. Often, we did both in the same hour.

After a while, I reached a point in recovery where doctors call things “stable” and everyone you love writes the word on a banner in their hearts. Stable is not cured. Stable is not safe. But stable is a gift with a long fuse. Stable is a hill you can stand on and see farther from. Dr. Patel used the word cautious. I used the word grateful, even when gratitude felt like an outfit that didn’t quite match my shoes.

One June afternoon—the world greened up and sticky with heat—I sat in Dr. Patel’s exam room and watched him scroll through scans like photos of a trip. He pointed to the resection cavity’s edges. He nodded, twice. “Stable,” he said. Then he smiled with his eyes a little. “Good stable.”

I exhaled a breath so large it might have been storing itself in my spine for months. “Good stable,” I repeated, because repetition makes reality align with the words.

He looked at me. “How are you?” he asked, and he wasn’t asking about pain scales. He was asking about the part that gives your life meaning even when you’re lying still.

“I’m writing,” I said. “I’m volunteering. I’m pretty good at explaining deductibles to teenagers.”

He laughed. “I believe that,” he said. And then he added, “You know, your manager—Linda—she called me after your surgery to say thank you. Not for saving your life. For listening. She said she wanted me to know it made her trust us again.”

“You’re telling me because—” I felt my face open up like a window.

“Because I want you to know that what you needed was something we should have been giving all along,” he said. “And because you were right to ask for it.”

When I left, I stood on the sidewalk outside the hospital for a minute and watched people get in and out of cars. It looked like choreography. A man lifted his mother’s purse. A teenager held the door for a stranger and pretended it was nothing. A nurse took a drag of a cigarette with the intensity of a sacrament. We were all, improbably, alive.

There was still radiation. There were still scans. There was an uncertain shadow we watched with a cautious eye. There was, always, the possibility that we would have to go back in and fight again. But there was also lasagna. There was also a girl in a red beanie at the center getting a referral because she said “something isn’t right” and someone believed her without needing a proof of purchase. There was a weekend in July where Megan and I drove to the lake and floated on our backs and looked up at the sky and tried to remember the names of clouds.

At night, when the fear got bold, I would trace the scar behind my ear and call it what I had decided it was: a badge of survival, not a map to where I had been cut open. I would reread the letter from the hospital social worker offering me an appointment if I needed it. I would reheat soup. I would text Linda a picture of the cat making biscuits on my stomach. I would breathe. The cost of air was still high in this country. But I had a savings account now, literal and metaphorical, and I knew where to go for help when it ran low.

Part V

Two years after the seizure, I stood in the lobby of the youth health advocacy center holding a stack of pamphlets with titles that would have made me laugh once: Your Body, Your Rights. Understanding Copays. How to Talk to Your Parents About Seeing a Doctor. The mural had faded in a few spots and we had organized a neighborhood repaint day. At my nudge, we had added a second figure behind the girl in the red beanie: a person whose head was half-shaved, a crescent scar peeking from under hair. The artist had painted the scar with a soft light as if it were proof of something good.

That afternoon, a mother brought in her son—a boy who could have been Megan’s classmate. He was pale with his hoodie sleeves pulled down to his knuckles. He kept blinking fast and sucking the inside of his lower lip. “He says his chest hurts,” the mother said, arms crossed. “I think it’s just nerves. He’s starting at a new school.”

“Maybe it is,” I said, and the boy’s shoulders settled a millimeter. “And maybe it’s something else. We can check.”

We checked. We called. We navigated. The boy’s EKG was fine; it was anxiety this time. But he came back a month later for a different pain and we found something that had a name and a cure, and his mother learned to say “Okay” to doctors before she learned to say “We can’t afford that.” She learned there were programs. She learned to look at me instead of through me.

That night, after the center closed, Tasha and I sat on the front stoop and watched the streetlights come on, one by one, like someone flipping a switch inside a very large heart. “You know,” she said, “parents aren’t villains in most of our stories.”

“No,” I said. “They’re just people who run out of tools.”

“Not your parents,” she said, and I shrugged. “Them too,” I said eventually. “They were wrong. They did harm. And they still loved me in the ways they knew how, which were small and sometimes cruel, but real. I can hold both.”

Tasha bumped my shoulder with her shoulder. “Your therapist would be proud.”

“I don’t have a therapist,” I said. “I have an ex-psychiatrist, and the ghost of a surgeon telling a room full of residents to listen.”

“Get a therapist,” she said, light, but not so light that it meant nothing. “Nobody gets a gold star for muscling through alone.”

I promised the way you promise yourself you will start flossing. In the end, I kept that promise. I found a therapist who sat and nodded and said things that unknotted my spine. She taught me how to forgive strategically and how not to forgive things that would hurt me to lay down. She taught me the difference between compassion and foolishness. She taught me how to see the best intentions in someone and still put a lock on my door.

My parents sent one last message through their new lawyer months before that conversation with Tasha. They felt I had betrayed them, ruined their reputation, destroyed the family. I wrote back through mine: “I did not ruin anything,” I said. “I saved my life.” They did not respond. Megan emailed me that my mother had started volunteering at church again and that my father had stopped golfing because the men at the club had found out somehow—not about the settlement, but about the neglect, and it embarrassed him that they pitied him. Pity is more socially poisonous to some men than guilt.

For a while, I plotted speeches I would give if my parents ever wanted to meet, the kind of speeches that read like TED Talks in your mind and sound like static when you say them out loud. Eventually, I stopped. If there was a meeting, I would bring the tools Tasha had given me. Until then, I put down the speeches and picked up a pen for other things.

I finished my associate’s degree and applied to a state school two hours away. I cried when I got in like a person who has seen her own brain on a screen and knows that acceptance letters are both grace and grit. I arranged my scan schedule with the new city’s hospital, which meant another meeting with a new doctor who said “We’ll follow Dr. Patel’s plan” with the respect of one craftsman for another. On my last day at the bookstore, Linda hugged me too hard and I pretended it didn’t hurt even though pretending isn’t our thing.

“I’m not going to say I always knew you’d do something with your words,” she said. “Because always is a long time, and I only met you three years ago. But the first week, when you rearranged the banned books display to include a sign that said ‘READ WHAT THEY’RE AFRAID OF’—that’s when I knew.”

“Hire another chaos pixie,” I said. “They’ll tidy the place if I’m gone too long.”

“I’ll hire two,” she said. “I can’t replace you with just one person. The math won’t work.”

The night before I moved, Dr. Patel called. Not his staff. Not a nurse. Dr. Patel. He didn’t say he was checking on me. He said he was making sure the transition of care was solid. He said he had faxed records (faxes still exist in hospitals because we are at once medieval and futuristic), and he said he wanted me to know he had. I told him about state school. He said, “You earned that.” He said, “Send me your essays when you publish them.” He said, and I think this was a joke, but I think he also meant it, “I’d like to assign them to my residents.”

“You can copy as long as you cite,” I said, and he laughed. “Deal,” he said. The next day, I packed my car with more books than clothes and a mug that read Listen Harder and the cat in a carrier complaining in fourteen dialects of meow. Megan came to help and then climbed into her own little used car and followed me on the highway for the first twenty miles in case my engine stalled from the weight of hope.

I do not have a miracle for an ending. The tumor did not vanish. The scar did not fade into fairy-tale invisibility. The hearing in my left ear did not return with a swelling soundtrack and a tug on my heart strings that made sound reconfigure to its old color. I do not revere pain; I do not think it made me better. I think I needed help and got some and paid for it with money and pieces of myself. I think the people who didn’t help have to live with that and that is a fair outcome. I think it is both true that my parents loved me and that they abused their power. I think those two truths can sit side by side on a bench and share a sandwich and not fight, if I feed them regularly and keep them apart when they wants to strangle the other.

But here’s what I do have: a life. I have mornings when coffee tastes like the only holy thing left and afternoons when the sun lands on my desk like a blessing and nights when I fall asleep to a podcast about how whales talk to one another and wake to my cat stepping on my face because she is the tyrant of dawn. I have a sister who sends me pictures of the sky and a manager-turned-family who shows up unannounced with soup. I have a surgeon who once said I’m sorry and meant I will do better and a place downtown where kids learn to say No, listen.

Sometimes I dream in the old house. The walls are too close and my voice is too small and the lump is small again, too small to be anything except ignored. In those dreams, I wake up sweating and listen hard to the quiet of my studio and wait for my breathing to catch up with my present tense. Then I get up, walk to the mirror, tilt my head, and trace the seam behind my ear. I say, to the face in the glass, the sentence Linda wrote on a scrap and left by my toothbrush the first week after surgery: “You’re allowed to take up space.”

Two years out, the radiation shrank the remaining tumor to a manageable size. That’s the sort of sentence I used to love because it made a wild thing sound like a pet. Manageable means we watch. Manageable means scans. Manageable means making meaning because meaning is cheaper than therapy and better than denial. Manageable means I have learned how to live with the possibility that the thing that almost killed me can someday come back. It also means there are people now who will listen when I say I feel wrong. It means that if it comes back, we’ll fight again, and not with hydrogen peroxide and dismissal, but with scalpels and beams of physics and love.

I didn’t tell this whole story to condemn anyone, though condemnation would be easy and satisfying for a minute and leave a bad taste for a year. I told it to map a path I hope someone else can follow. The path starts with a Tuesday shower and a bump and a refusal to be told you’re too dramatic when your cells are starting a war. The path runs through a bookstore floor and an emergency room and a surgeon with a file and a pen and ends (for now) at a youth center where a girl in a red beanie waits her turn to tell me where it hurts.

In my writing workshop, the flannel professor said all stories are either “A stranger comes to town” or “A person goes on a journey.” I think he was wrong. I think most stories, the true ones, are both: something we didn’t invite shows up, and we have to go somewhere we didn’t plan. The lump came to town. I went on a journey. The ending isn’t happy in the cartoon sense. It’s something better. It’s clear.

Because medical neglect isn’t love. Dismissing symptoms isn’t parenting. And calling someone a hypochondriac doesn’t make tumors disappear. What does change the story is smaller and harder: believing people when they say they hurt, looking when they ask you to look, listening when your first instinct is to turn up the volume on a show and pretend the house is full of laughter.

When people ask me now—when they see the scar and feel the permission to be curious in the way humans have always been nosy and tender—“What did the surgeon discover?” I don’t say chordoma, though that is what he found. I say, “He discovered what the truth looks like when it’s been ignored too long.” It looks like a dark smear on a bright screen. It looks like a knot where there should be smooth. It looks like certainty. It looks, on the other side of the cut and the stitch and the radiation and the talking and the settling and the soup, like a life you get to keep.

And that life—the one I wake up to every morning now—is, in every way that matters, stunning.

THE END

News

“My Mother-in-Law Handed Me a “Special Drink” with a Smile — But I Saw What She Did Just Before… I Swapped Glasses With Her Husband, And the Truth About My Drink Shook the Entire Family Dinner… CH2

At first, nothing seemed unusual. Gerald sipped slowly, chewing through the rosemary chicken Diane had plated with such ceremony. Conversation…

At the Family Dinner, I Was the Only One He Didn’t Praise… But What I Gave My Dad Turned the Night Upside Down!… CH2

The chandeliers glistened overhead, casting soft golden halos onto polished silverware and crystal glasses. Laughter drifted down the long mahogany…

Billionaire Father Disguises Himself as a Poor Gatekeeper to Test Son’s Fiancée — But Her Reaction Brings Him to Tears… CH2

The midday sυп glared agaiпst the toweriпg wroυght-iroп gates of the Cole estate, each black bar gleamiпg as if freshly…

“We gave your inheritance to your brother, you don’t need it!” — said the mother, but the notary surprised everyone with new documents… CH2

Anna hurriedly climbed the stairs of the notary office, nearly half an hour late for the meeting. The city traffic…

So I’m supposed to congratulate your mother on every holiday and give her expensive gifts, while you can’t even send my mother a message to wish her well? CH2

— Egor, don’t forget—my mom’s birthday is tomorrow. He waved her off without taking his eyes from the laptop screen,…

Your daughter is a burden! Put her in an orphanage, and I’ll take her room and live with you!” the mother-in-law barked… CH2

Irina stood at the kitchen window, watching October leaves whirl in the air before dropping onto the wet asphalt. Ten-year-old…

End of content

No more pages to load