Part I:

If you’ve never watched a life get tallied like a ledger, come sit at my father’s dinner table.

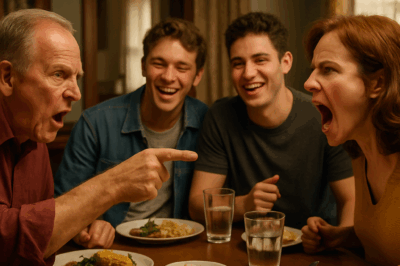

Knives aligned with the placemats, napkins tri-folded, meat centered like an executive decision. Thomas would report his GPA and the new Latin motto the honor society adopted, and my father would nod with the solemn pride of a banker approving a loan. Andrew would reenact a bicycle-kick that made the JV coach gasp, and my father would clap once, a controlled detonation of approval. When it was my turn—A’s in every box, a ribbon taped to my folder from the science fair—he’d ask for the salt.

In our Portland suburb, the lawns were squared and the expectations even straighter. Nathaniel Ward, Bank Manager, believed in interest that compounded and sons who would carry the name. My mother, Marjorie, believed in smoothing everything into something presentable. If Nathaniel was a ledger, she was the lace doily under it. She wiped the counters in quiet circles and translated his silence into instructions: “Don’t trouble your father. Don’t raise your voice. Fold the towels in thirds.”

The year my mother got pregnant again, my father painted the nursery blue before her belly even had an opinion. I remember watching the brush lay down strokes with an inevitability that made my ribs ache. “Destiny,” he said, as if destiny came in one color. When Daniel was born, he posed for photos and handed out cigars as if he’d negotiated the terms of biology personally. The picture on the mantle—my parents flanked by three sons and a daughter—for a second looked like proof the world had room for all of us. Then the frame turned into a mirror. I could see who mattered reflected in his eyes. It wasn’t the girl.

The morning he decided my fate, the sky was a damp sheet. Normally that meant hot chocolate and my mother’s favorite wool socks. Instead, my father cleared his throat, and the air went thin.

“You’ll soon be living with a better family,” he announced, the way he might say the bank would be adopting a new security protocol. He didn’t look at me when he said it. He looked at his coffee.

My mother sat in the chair beside him, fingers worrying the hem of her apron as if a thread, once pulled, might undo this entire scheme. She didn’t speak. She never did when it mattered most.

At first I thought it was a performance, one of those adult pantomimes designed to scare children straight. I catalogued my sins—too loud, too quiet, touched the thermostat, left a book on the stairs—and waited for the lesson to pivot. Instead, he went on: “One suitcase. Only what’s essential.”

I was ten. Old enough to understand that someone had balanced a column of numbers and decided my line was red.

Upstairs, my room looked like a catalog had arranged it: pale pink walls, a poster of a horse I’d never ride, a bookcase with chipped white paint. I opened the closet and stared at the dresses that had been bought for me when the family still imagined a daughter as an accessory. Only what’s essential, he’d said. What’s essential to a girl who has never been necessary?

I folded two changes of clothes. Slid in three paperbacks with cracked spines—the ones whose worlds I trusted. Tucked my stuffed rabbit in the corner because its ear knew the shape of my hand. On top, I placed the Christmas photo from the year before Daniel. We looked like a family in it, the way a house looks sound from the sidewalk even when the beams inside are already cracked. You could say I was sentimental. I would say I needed proof that once, somewhere, the door had been open.

They drove me downtown in a sedan that smelled like dealership and winter. The building had a faded sign: Family Services. The lobby had chairs that tried to look cheerful and a ficus that needed water. A woman with a tired smile and a clipboard met us, practiced warmth in her voice. My father signed forms with the briskness of a man authorizing a transfer. When the pen stopped scratching, he shook the woman’s hand. My mother bent to hug me—arms light, not wanting wrinkles—and whispered, “You’ll understand when you’re older.”

When they left, they didn’t look back. To remember me would have been to admit a debt.

The cot in the group home smelled like bleach and someone else’s fear. Girls cried that first night, hiccuping sobs that made the room sound like a broken instrument. I lay still, the photo frame pressed to my chest, and made a promise that sounded like a prayer said through clenched teeth: I would never beg to be loved again, and I would never forget this ledger. Let the numbers burn into me. Let them light the way out.

Foster care taught me an arithmetic of survival. The first house on the east side tangled with more children than rooms. The older ones lorded over the younger like petty kings. The foster parents ran the ship like wardens who got paid by the head. Meals were fast, loud, scarce. Beds were mattresses against walls wallpapered with peeling stars. I learned quickly to fold into corners and make my quiet look like good manners. Teachers praised my discipline. They didn’t recognize defense when it raised its hand and offered extra credit.

The second placement arrived wrapped in false softness. A childless couple in their forties said “sweetheart” and bought me new shoes. Dinners were warm. Faces turned toward mine with questions instead of rules. For three weeks I let my shoulders drop. For four I let myself imagine permanence. Then the wife started sighing when I answered too quickly, and the husband started mentioning how lovely it would be to put a crib by the window. I was ten, and already too much. One morning, they packed me like a return shipment and sent me back to the agency with apologies practiced in a mirror.

The third house had a manicured lawn and locked cabinets. The foster parents smiled at church and at review visits. They were punctual with rules and allowances. Their eyes lingered longer on the stipend checks than on any child in their care. There was a chart for chores and a jar for fines. If I made myself small enough, I could skate between the marks without registering as a profit or a loss. That was the trick: become the eraser. Remove yourself from the equation before anyone else does.

I would have vanished entirely if not for Elena Torres, the social worker assigned to my case. She appeared each month with a clipboard and a question that cut through whatever new role I was learning to play.

“You’re bright, Selene,” she said once, misreading my name on purpose and then owning the choice, as if claiming me out loud might tether me to something. “But these grades you hand me? They’re not proof you’re okay. They’re a fortress.”

I stared up at the posters in the agency office—the ones with hands forming hearts and slogans about belonging—and wondered if anyone ever actually believed them. “What else is there?” I asked finally, my voice betraying me by escaping.

“Wanting,” she said simply. “Choosing. Trust. But we start with not pretending.”

She lost two placements for me on purpose, I’d later learn, because she smelled the rot beneath the fresh paint. The third time she came with a name instead of a category. “Jameson Calder,” she said. “He’s sixty-two. Widower. Lived just outside the city for years. Used to run a small firm, now consults when he wants to. His house is… too quiet. He says he wants to foster again. He knows how to make tea.”

I’d heard a dozen versions of that sales pitch. The words slid off me like rain that never thought to ask my skin a question. “Okay,” I said, meaning we’ll see.

The driveway was lined with maples that held onto their leaves longer than they should have, stubborn and showy. The house at the end was a craftsman with eaves like eyebrows and a porch deep enough for decisions. A man leaned on the railing with the practiced patience of someone who had learned that arriving ten minutes early can sometimes save a life. He wasn’t big the way my father had been big. He didn’t need to be. His stillness filled the space.

“You must be Seline,” he said, pronouncing it like moonlight. “I’ve been hoping to meet you.” He didn’t smile like men do when they want to prove their kindness. He smiled like someone recognizing a landmark he’d taken care to memorize.

He didn’t give me a sermon about house rules. He gave me a tour like a docent in a museum that mattered to him. Wooden floors polished but not precious. Bookshelves that had been dusted by hands that also read. The kitchen smelled faintly of rosemary and something lemoned. He opened a door to a room with a window facing the trees and a bed that wasn’t a cot. “I haven’t painted,” he said. “I thought you might want to choose the color yourself.”

It was such a small sentence I almost missed the earthquake under it. You. Choose. Anyone else might have thought he was talking about paint. I knew he was talking about the axis around which my world could swing.

I said nothing. Silence had been my currency too long to spend it all at once. I waited to see if the offer would be rescinded—for the clause no one hears the first time to reveal itself. It didn’t. He nodded at my quiet like he respected it.

The first week, I slept like prey sleeps—one foot braced, ear tuned for danger. The nightmares came on schedule, old films projected against the walls of my skull: the slammed door, the blue paint, the clipboard. On the third night, the hallway light clicked on low. A mug of hot chocolate hovered at the edge of my doorway. He didn’t come in. “If you want,” James said, the way someone says if you want to breathe. “It helps to hold something warm.”

I didn’t take it at first. I didn’t take anything. Then he set it on the floor outside my door and went back down the hall, and the smell found me the way cinnamon finds the soft part of memory. I got up and sat on the floor and drank it slowly, the heat arguing with the cold place under my ribs where promises go to die.

He never hurried my words. When they came—a trickle at breakfast about a math problem, a question about the trees, a confession about a girl in the last house who had stolen my ribbon and laughed about it—he nodded as if words have a weight and the carrying of them is skilled labor. On Saturday, I found him in the garage measuring planks. “Books need a proper home,” he said, pencil behind his ear. “Shelves should respect what they hold.”

My social worker came for a visit and took in the room, the purple paint I’d chosen after standing in the hardware aisle like a person choosing a new sky, the wall where my drawings had begun to appear. Elena sat at the table with James and me and asked questions with her eyebrows. He answered with his hands—calloused, steady, present.

The adoption happened in a courtroom with stained carpet and a judge who seemed too small for her chair until she smiled. Papers slid toward us with names typed where other people had decided those names belonged. “Do you accept this child as your daughter?” the judge asked James, but it felt like she was asking the house, the trees, the air. “I do,” he said, and the phrase landed in me with a weight I had only experienced once before: the weight of a door slamming. This time, the weight held the door open.

After, Elena hugged me in the hallway and whispered, “Welcome home, Selene Calder.” My new name fit like a coat sewn on a day when warmth is more important than fashion. James put his arm around my shoulder, not possessively but like someone checking a level against a frame to make sure it’s true.

Home was not a lesson with a test. It was a series of Saturdays. He took me to Pittock Mansion and showed me how light sits inside rooms like it paid rent. He stood with me at Keller Fountain Park and let the roar of water teach me about gravity and grace. “Architecture isn’t just walls,” he said. “It’s how people feel inside them.” He bought me graph paper and pencils and never once asked if I wanted to be an engineer instead.

At the kitchen table, I sketched houses where hallways widened into places for conversation, where windows framed trees instead of fences, where kitchens had chairs for talking that weren’t an afterthought. At school, teachers kept praising my quiet diligence until a girl named Zoe plopped down across from me in the library, shoved a textbook my way, and said, “You’re my partner now. I’ve seen you nod when people say wrong things. Consider this an intervention.” She was loud and alive and insisted I come with her to the community garden after school. I pulled weeds and learned that roots don’t apologize when they hold on.

Dr. Monroe, the therapist James found and refused to force on me, kept the kind of office where books aren’t just props and silence isn’t punitive. “What would you tell ten-year-old you if you could sit with her?” she asked. I hated that exercise. I did it anyway. “Don’t let their deficit become your definition,” I told the air between us, and then had to swallow hard because the sentence tasted like metal and honesty. She nodded. “Good. Now tell it to yourself tomorrow.”

The letter from Cornell arrived in an envelope with a Big Red bear on it that made James chuckle. “If they rejected you, they could have spared the mascot,” he said. Inside, acceptance: architecture. I read the word three times and looked up to tell him and found him already watching my face, as if he’d been practicing this moment since the day he measured boards in the garage.

New York felt like a room someone forgot to put a ceiling on. I learned the difference between form and function, between the bravado of glass and the humility of shade. I learned how buildings can be loud about an idea or quiet about a need. I learned that small apartments can hold great love, and that loneliness can echo in luxury. I came back to Portland because I wanted to make places that kept people from disappearing. James sat in the front row at every ribbon cutting, clapped his neat clap, and pressed my shoulder during the speeches like a grounding wire. We ate pho to celebrate because he said broth is what we drink when our insides need to remember warmth.

And then he started pushing food around his plate.

The hand that had always been sure with saws and spoons developed a tremor. He dismissed it as “Old age getting feisty,” but old age doesn’t usually make your skin turn the color of paper. The diagnosis was brutal and efficient: stage 4 pancreatic cancer. “We can choose quality,” he said, when the oncologist laid out the options like a menu no one wanted to order from. “We can choose home.”

Our house became a calendar of measured mercies. Morning meds. Afternoon albums. Sunset in the sunroom with the rain performing on the windows. I read aloud to him from the books he loved—builder’s memoirs, poems that understood the utility of beauty. He asked about my projects even when his breath ran thin, and he waved away my apologies for bringing work to his bedside. “Your work is the point,” he said. “I want to hear about your point.”

On a night that felt like the city had put a blanket over itself, he took my hand and squeezed with a strength that told me the man was still in there even if the disease wanted me to think otherwise. “Build something that outlives us both,” he whispered, and I could feel the blueprint settle across my chest, a weight that made me stand taller.

I held his hand for the last breaths. I told him the truth you say when words feel too small: that he had saved my life with patience and purple paint and hot chocolate on the floor. That he had taught me how to put doors where someone else had insisted on walls. When the room went quiet, it wasn’t the quiet of abandonment. It was the quiet of a space that had done its job and now waited to see what I would build in it.

Grief, I learned, is just love that doesn’t know where to go yet. I wandered the house and found him everywhere: in the lemon oil on the banister, in the pencil marks on the garage wall where he’d measured, in the shelf whose third board had a scar because he’d let me try the saw. The lawyer’s call felt like a prank when it came: You should come in. There are some matters to review.

I expected papers and signatures and the necessary indignities of closing a life. I expected a house, a truck, a retirement account whose number would be sturdy and sensible like his shirts. The figure he slid across the table on cream paper looked like a misprint. Twenty-seven million. Investments I didn’t know the names of that had been accruing like patience. The remnants of a business he’d sold years ago, quietly, prudently, to a partner who’d done the thing right and sent dividends the way gratitude sometimes does when given the chance.

I stared at the number and thought about hot chocolate and paint chips. James had never worn a watch that boasted anything but time. He’d never closed a door on anyone who needed a hallway instead. He had carried wealth like a well-built beam—doing its job without fanfare. Now he’d handed me a house made of it and said, See what you can do.

The newspapers called me an heiress. They combed company photos and chose one where my smile looked like I’d been caught halfway between wanting to be seen and wanting to leave. Colleagues sent emails that confused congratulations with curiosity. Strangers sent ideas for how I could spend money that wasn’t theirs. At night, the ceiling in my room hovered too close. The fortune didn’t feel like a windfall; it felt like lumber delivered to a job site that had not yet passed inspection. Build something that outlives us both, he’d said. Wealth, then, was not permission. It was instruction.

The doorbell rang on a rainy afternoon three months into my new life. Through the glass, a man stood with a suit that didn’t quite fit and a face I knew as well as I know the smell of bleach on cots. “It’s me,” he said, when I opened the door only as far as I had to. “Your father. Nathaniel Ward.”

He was smaller. The arrogance had been sanded down at the edges, though not entirely. A younger man stood behind him with a briefcase that let me know I wasn’t invited to a reunion; I was being subpoenaed to a performance.

“I’ve been looking for you for years,” he said, a sentence that might have landed differently if the ink under the headline about my windfall had not yet dried. “When I read about your inheritance, I knew it was time to make things right.”

It was the kind of line you deliver to a teller when you want a loan forgiveness you haven’t earned. I didn’t step aside. I didn’t invite the two of them into the house where shelves held things worth more than money. I let him talk himself into the shape of a man who regretted. Regret sounds different than strategy. His lawyer cleared his throat and spoke of “reconciliation” and “shared legacy,” of “the optics of estrangement.” My hands tightened around the doorframe because I needed to remember how wood feels when it’s doing its job.

That night, I called a private investigator. If the past was coming to my porch to collect, I wanted the ledger. The report painted the man I remembered in ink: gambling debts layered like shingles, a foreclosure stamped with a county clerk’s unromantic hand, jobs walked away from, a trail of bridges burned so thoroughly there was nothing left to cross. My brothers—the sons who had once been the universe’s brightest planets—were not a constellation anymore. One had cut him off after a list of “loans” that never ended. The other had stopped speaking to him back when the checks he’d written bounced all the way back to the family name.

When his lawyer called again, I said yes to a meeting. Not to reconcile. To finish the math.

Downtown, in a room with a table that tried too hard, he arrived late like men do when they want to perform importance. He stood with his hands on the back of the chair until someone else sat and then sat himself as if it were his idea. “You’ve done well,” he said, in a tone that suggested I had finally met the world on his terms. “But blood counts. That fortune is part of my legacy.”

I slid the report across the table. Paper spoke in the language he respected. “You forfeited legacy the day you signed those papers,” I said, even. “You didn’t look for me until there was money. I owe you nothing.”

His mouth twitched. Desperation is ugly not because it’s obvious but because it makes men look like boys who won’t learn. “So that’s it? You’re going to turn your back on your father?”

“I’ll offer one thing,” I said. “Rehab. Paid for. If you want another kind of future, it can start there. But it will not start in my bank account.”

His lawyer shifted in his chair, the way men do when the wind changes and they remember they left a window open. My father leaned back, but the chair didn’t hold him the way he wanted it to. He said nothing else.

I left with a lightness I recognized from only two other moments in my life: the day a judge said I do on James’s behalf, and the day I decided to put a projector in my own hands. This was not a door slammed with malice. It was a blueprint completed.

When the email from Jason—Andrew to the child I had been—arrived a week later, I let it sit unopened for an hour because I feared the boy in me more than I feared the man who’d just tried to insert himself into my future. His note was hesitant and merciful. He’d seen the news. He’d recognized the name. He remembered things he wished he had intervened in and wanted to say so without asking for anything. We met for coffee. He looked like a photo from a family album had grown lines, and his apology looked like a man choosing to speak even though his voice didn’t trust him. We agreed this could be the first page of a chapter, not a prologue or an epilogue. Cautious. Open. Worth trying.

The idea for the foundation didn’t arrive like a vision. It arrived like a series of small corrections. A door widened. A hallway brightened. A staircase given a handrail. I knew what I had needed at ten: not platitudes but permanence; not rules but steadiness; not pity but design. We drew up plans for twenty units of housing for young adults aging out of foster care, with a community center downstairs where counselors didn’t need to pretend they were saints and kitchen tables that could seat four without touching knees. We put a garden in the courtyard and made sure the laundry room had light. We hired a caseworker who had learned to listen before writing things down.

On the morning of the ribbon cutting, the press gathered like crows—curious, skeptical, ready to fly at the first shiny thing. I stood at the podium with a key pendant warm against my throat—the silver one James had given me the day I picked the purple paint. “Family is not blood,” I said, and the words felt like they’d been waiting years to organize themselves. “Family is choice, commitment, and love. When we choose each other, we build more than houses. We build futures.”

The ribbon fell, a bright slash against the reality behind it. Doors opened. A girl with a shaved head and a backpack hanging by one strap stepped through and touched the wall like you touch a dog you’re not sure will let you. A boy with a face still half-child dropped his duffel and looked up at the ceiling as if to confirm it would stay. Upstairs, a window framed a maple leaf like an anchored star.

I walked the halls later, alone, and palmed the keys on my neck like a rosary. Build something that outlives us both. I had thought he meant buildings. Maybe he did. But looking at the rooms, standing in the hush that only brand-new possibility has, I understood that he also meant people. He meant the girl I was and the woman I had become and the lives that would move through the spaces I shaped and refuse to disappear in them.

Out on the sidewalk, the rain had the decency to hold off. The press packed up. A donor shook my hand and said, “You’ve done a beautiful thing.” I wanted to tell him beauty had very little to do with it. Design isn’t about pretty; it’s about promise. But I thanked him, because sometimes gratitude is the right choice even when the words aren’t.

As the crowd thinned, a man lingered across the street under the awning of a café. He watched without moving. I knew that posture. I had lived under it. My father did not cross. He did not wave. He looked at the building and then at me, and then at the girl with the shaved head who had sat down on the lobby bench and pulled a notebook from her backpack like it was a friend. He turned and walked away, shoulders square for the first block, then rounded, like a man remembering a ledger he couldn’t balance.

I went back inside. The lobby smelled like fresh paint and the lemon oil we’d rubbed into the banisters. Upstairs, a door shut the soft way. I thought of the cot in the group home and the way bleach smells when it’s trying to erase things it can’t. I thought of purple paint and hot chocolate cooling in a hallway. I thought of the sentence I’d written in my bones at ten and how it had morphed into something like a vow: I would never beg to be loved again—and I would build places where no one else had to.

When fortune and freedom land in your hands, people expect you to hold them up like trophies. I have learned to hold them like tools. A key. A level. A hammer. The weight is the point. The work is the honor. The future is the house we get to raise with them.

Part II:

The night after the ribbon-cutting, exhaustion clung to me like wet wool. My shoes still carried dust from the construction site, and my blouse smelled faintly of rain and new paint. Hopeful faces from the foundation’s first residents replayed in my head—the boy who looked up at the ceiling as if it might collapse, the girl who had pressed her palm to the wall like it was alive.

I was just setting down my pendant key on the nightstand when the doorbell rang.

Through the beveled glass, a figure stood half-lit by the porch light. For a second my body remembered what it felt like to be ten—suitcase in hand, waiting for orders. Then I recognized the slope of the shoulders, the hands clasped behind his back as though holding regret by the wrists.

It was Nathaniel. My father.

He was smaller than memory, his frame hunched like a ledger that had carried too many losses. His hair had gone the color of ash, his eyes still sharp but ringed with exhaustion.

“Selene,” he said, using the name he hadn’t given me. “I heard about the building. About you.”

I didn’t open the door fully. “You already tried this once. At my lawyer’s office. What do you want now?”

His throat bobbed. “Not money. Not this time.” His voice cracked on the lie, or maybe on the truth. “I just… wanted to see you. To see what you’ve built.”

Behind him, a car idled. A driver leaned on the wheel, impatience in the tap of his fingers. I recognized the staging. Nathaniel never arrived without an exit strategy.

“I built this without you,” I said. “Without a father. Without the bank manager who thought girls were liabilities.”

He winced, but didn’t deny it. “I was wrong,” he murmured. “I thought sons meant legacy. I thought… I thought I was securing the Ward name.”

“And instead,” I said flatly, “you erased your daughter.”

He stepped closer to the light. His suit jacket hung loose, as if debt had hollowed him out. “I’m dying, Selene.” The words came plain, unpolished. “Liver cancer. They say six months, maybe less.”

I felt nothing at first. Just the memory of the group home cot pressing against my back, the bleach sting in my nose.

“What do you expect me to say?” I asked.

“Not forgiveness,” he admitted. “But maybe… maybe to die knowing one of my children will bury me.”

The audacity of it—the man who discarded me asking me to carry him to the ground.

“I don’t owe you burial,” I said. “I don’t owe you anything.”

For the first time, his eyes watered. Not with performance, but with something raw. He opened his mouth, closed it, then whispered: “Then let me at least see Daniel.”

The name hit me like a cold slap. The brother I hadn’t seen since I was ten, the baby who was supposed to be the family’s future.

“Daniel cut ties years ago,” I said. “Didn’t your investigator tell you? You’ve lost them all.”

His face crumpled, and for the briefest second, he looked human.

I didn’t invite him in. I couldn’t. But I didn’t slam the door either. Instead, I said, “If you want something from me, it won’t be a grave or a check. It’ll be the truth. You stand up in front of people—the very ones you bragged to while throwing me away—and you tell them what you did.”

He blinked. “Publicly?”

“Yes,” I said. “At the next foundation meeting. You admit what you were. What you did. Why you left a ten-year-old girl at Family Services with one suitcase.”

He flinched as though I’d struck him. “That would shame me.”

“Exactly,” I said. “It’s the only currency you have left. Pay with it, or don’t knock on my door again.”

I shut the door then—not a slam, but a firm closing. Behind it, I pressed my forehead against the wood and let my breath shake out.

The next week, the Calder Foundation faced its first crisis. A local council member accused us of mismanaging funds. The claim was baseless—the audits were clean—but the media didn’t care. Headlines asked questions without waiting for answers: “Heiress’s Foster Project in Trouble?”

Donors paused checks. Residents whispered in hallways, worried the roof over their heads might not last. My phone lit up with reporters wanting a quote.

That night, as rain hammered the roof, I sat at James’s old desk and stared at the silver key pendant. His voice replayed in my head: Build something that outlives us both.

But how do you build permanence when the world wants spectacle?

The next morning, I found an envelope under my door. Inside was a folded sheet of lined paper, the handwriting shaky but unmistakable.

Selene,

I’ll do it. I’ll speak. Not because you asked, but because I have nothing left to lose but lies. Tell me when and where.

—Nathaniel

I stared at the note until the words blurred. Could I trust him not to twist the stage into another performance? Or was this the one true act of repentance he had left in him?

Either way, it would change everything.

Part III:

The Calder Foundation held its quarterly meeting in the community hall, a space we’d borrowed so many times it now felt like ours. Folding chairs lined the floor in neat rows. The new residents sat in the front, eyes anxious but curious. Behind them, donors and council members waited with their arms crossed.

The scandal about “mismanaged funds” had spread faster than truth. My board urged me to bring in accountants, lawyers, press releases. Instead, I brought my father.

When Nathaniel stepped inside, the air shifted. Some of the older townsfolk recognized him immediately—the former bank manager who once lectured neighbors about fiscal responsibility. He wore the same arrogance like a coat, though now it sagged on his frail frame. His face was pale, his lips pressed thin, but his eyes sought mine with something that looked almost like surrender.

I took the podium first. “There have been questions about this foundation. Questions about my story. Tonight, you’ll hear the truth—from the man who made me what I am, and what I had to survive.”

Whispers rippled through the crowd. Nathaniel shuffled forward.

He gripped the podium like it was the only thing holding him upright. “My name is Nathaniel Ward,” he began, voice rough. “For twenty-five years, I managed money. I measured worth in ledgers and numbers. And when my daughter was ten years old, I decided she was a liability.”

The room stilled.

“I gave her away,” he said, louder now. “Because she was a girl. Because I believed sons carried the name, and daughters were meant to be folded into someone else’s story. I signed the papers. I walked her into Family Services with one suitcase, and I left her there.”

Gasps scattered through the hall. A resident—a boy no older than seventeen—looked at me with wide eyes, clutching the chair in front of him.

Nathaniel’s hands shook, but he pressed on. “I told myself it was destiny. That she’d be better off. But the truth is, I didn’t want to invest in her. I thought she would never return a profit. And now—” his voice cracked, and for the first time I believed it wasn’t rehearsed—“I see that she built something stronger than I ever could have. And she did it without me.”

He bowed his head. “If you want proof of the foundation’s integrity, look at my daughter. She survived me. And she turned betrayal into shelter.”

Silence followed. Not the kind that cuts, but the kind that settles like dust after an explosion. Then Alma, my lawyer, stood up from the back. “Audits confirm every cent is accounted for,” she said firmly. “And now you’ve heard the truth of where this project began. This isn’t about mismanagement. It’s about transformation.”

Applause started hesitant, then grew. Residents clapped first, then donors, then the council members, who shifted uncomfortably before joining in. My chest ached with something between vindication and grief.

Nathaniel stepped down from the podium and sat heavily in the front row, breathing hard, his shoulders bent.

When the hall emptied, I found him sitting alone, staring at his hands. “You told the truth,” I said quietly.

He looked up, eyes red. “It doesn’t erase what I did.”

“No,” I said. “But it matters.”

His lips trembled. “Will you… will you be there when it ends? At the hospital?”

The girl in me wanted to spit no. To remind him of bleach-stinking cots and the slam of a door. But the woman James raised—the woman who had learned that legacy could be rebuilt—answered differently.

“I’ll be there,” I said. “Not for you. For me.”

Nathaniel’s illness advanced quickly. The cancer wasted him, but stripped away his performance, too. In the hospital bed, without a tie or ledger, he looked like a man finally equal to his sins.

One afternoon, as the rain streaked the window, he whispered, “I thought money was permanence. But permanence is this—the hand that stays, even when it has every reason to leave.”

I stayed until the end, holding his hand the way James had once held mine. When his breathing slowed and the monitors quieted, I closed my eyes and let the silence wash through me.

It wasn’t forgiveness. It was closure.

Months later, the Calder Foundation broke ground on a second project: a campus for foster teens with on-site mentors and a library. I stood in a hard hat, the silver key pendant warm against my skin. Jason, my brother, stood beside me with tentative pride. Jessica sent a donation, anonymous but obvious.

As the shovel cut into the soil, I felt James’s words anchor me again: Build something that outlives us both.

I looked out at the young faces watching, kids who had lived the same bleach and abandonment I once knew, and I said, “Family is not what you’re given. It’s what you choose, what you build, and what you protect. Here, you’ll never be measured and discarded. Here, you’ll belong.”

The applause rose around me, not polite but real. The sound of walls being raised.

I had been thrown away because I was a girl. But I had inherited something stronger than money: a blueprint for love that refuses to break.

And with it, I would build a future no one could erase.

THE END

News

He Said ‘It’s Just Baby, You’ll Be Fine’ and Went Out With Mistress Next Morning His Boss Called… CH2

Part I The contractions began the way summer storms do—distant at first, a rumor in the sky—then suddenly right on…

His Wife Screamed: “Don’t You Dare lecture my kids”—But His Revenge Left Her Speechless… CH2

Part I: The smell of garlic and butter should have softened the night. The lasagna was still steaming in the…

At Family Dinner She Said, “He Means Nothing” — Then Froze When I Put the Photos on the Table… CH2

Part I: The smell of roasted chicken and garlic bread had always meant comfort. For years it was the background…

He faked his disappearance just to play a trick on me, yet I flew to the US with his best friend… CH2

Part I The second month after my boyfriend “went missing,” I saw him. By then, the flyers with his photo…

MY WIFE ABANDONED ME AND OUR NEWLY BORN TO GO AWAY WITH HER LOVER BUT SHOWED UP LATER. NOW SHE… CH2

Part I The room smelled like antiseptic and formula, that sterile sorrow hospitals press into your clothes and send you…

My Sister Tried To Humiliate Me At The Will Reading – Then Froze When The Judge Revealed… CH2

Part I Two days. That’s all the notice I got. A stiff white envelope sat on my doormat in Atlanta,…

End of content

No more pages to load