Part I

I was making lists—the kind you make in December when you’re trying to pretend the holidays are logistics and not landmines—when my son’s phone buzzed on the coffee table. He’d gone to his room to finish a write-up on cadaveric anatomy (his first winter break in med school and still, he studied like the body was a mystery that deserved soft hands). I don’t snoop. But the lock screen lit with my mother’s group email—Christmas dinner, please confirm allergies—and under it a notification from a social feed I barely use anymore.

Curiosity is a petty thief that steals only an inch at a time. I picked up my own phone, opened the family chat, and saw what might as well have been a bloodstain.

My nephew—my brother’s son, polo collar and practiced smirk—had posted a meme: a toddler with a plastic stethoscope from a toy doctor kit, captioned, “Graduates from Crestwell Med be like: ‘I diagnose you with vibes.’” Beneath it: laughing emojis from boys who all look like they were printed on the same prep-school factory line. And there, blue and simple like a stamp, was my father’s approval—a thumbs-up.

I wish I could tell you I gasped. I didn’t. I felt something slide out of place in my chest, not a break—just a shift, the way a picture frame tilts after a slam somewhere else in the house.

My son didn’t know. He was in his room probably writing a Christmas card in that neat handwriting he inherited from no one in this family, something like “Thank you for always believing in me.” He believed people when they said things like tradition and family. He’s a good kid. The kind people claim they raised on purpose.

A few hours earlier my mother had called. No room this year, she’d said in that breezy tone she uses when she wants the logistics to feel like a mandate. The table is tight. So many guests. You understand. In the background my father’s voice, careless and cutting: “Losers aren’t welcome for Christmas.” Laughter from someone else. A clink of glass. I hung up and stared at the wall for a long time. When you’ve trained yourself to accept small humiliations, the big one arrives and knocks politely.

We are not wealthy. We are not sitcom poor either. We are the American middle—paycheck to paycheck in nicer clothes. My son chose a local medical school, not Ivy, not top-ten, but accredited, solid, with a partial scholarship that meant he could live at home and come out without debt. He got into the big-name place, too. He said no to it the way you say no to an affair: quietly, for your own sanity. He watched me for years making payments with a second smile that never touched my eyes. He knows the shape of a bill through an envelope.

My parents are career academics—science, small offices, coffee-stained journals, feuds conducted in footnotes. They aren’t rich, but they wear prestige like armor. They built an altar to ranking. The god’s name is Name—as in the name on your degree. If Harvard offered a master class in boiling water, my parents would camp out for tickets and call it an investment in culture.

They invested in my brother. Tutors, camps, coaches, a laminated schedule pinned to his door. By the time I was five, the fridge held flashcards with words like selectivity and rigor. When my brother got into a gilded law program, they framed the acceptance email and took us to a restaurant so expensive the water had an origin story. They paid for all of it—tuition, housing, snacks. He was the family’s portfolio.

By the time it was my turn, the market had crashed. We’d love to help, they said, but things are tight. Loans are normal. You’ll be grateful later. I went. I did everything right. I walked across a stage with a shiny diploma and a hundred grand tied to my ankles. When the first payment auto-drafted, no one clapped.

Fast-forward twenty years, and I’m in my early forties, good job, decent health, debt like a second spine. When my parents retired, they confessed struggle and I believed them. I started sending money. Grocery bills. Power. A little became regular. I skipped vacations, delayed a roof fix, sharpened the budget until it cut. I thought that’s what good daughters do.

So when my mother said there wasn’t room and my father said loser, something in me unlearned a language. I sat on the couch with my list of yams and pie crusts and napkins and I crossed out show up and smile. I wrote do not go. Then I didn’t shout. I dialed.

There had been an email—Christmas dinner, confirm allergies—with eighteen names I knew like cousins even if they weren’t legally anything. People I’d grown up calling Aunt and Uncle, who sent my son Starbucks gift cards and books about space. They weren’t just my parents’ people. They were ours.

I called them one by one. We won’t be there, I said. They uninvited my son. I did not campaign. I did not weep. I said facts like they were ingredients on a label. Some were stunned into honest language you can’t print on nice linens. Some went quiet. Then came the breath—the one you take when you realize you are about to choose.

By Christmas Eve, thirteen had chosen. We’ll be there. Your son is family. We didn’t know. My brother’s wife texted late, clandestine. I’m coming. Don’t tell Mark. For once I didn’t feel petty excluding him and their prodigal prodigy. I felt… precise.

That night I stood in my son’s doorway. He looked up from Netter’s Anatomy, eyes soft with exhaustion and good humor. “I need to tell you something,” I said, and told him the whole thing—the call, the background voice, the meme, the like. He listened. When I finished, he closed the book gently, stood, and walked to his room. The door clicked shut like a period. No meltdown. No brittle smile. Just punctuation. It hurt more than anything.

I washed dishes I hadn’t dirtied. I wrote 13 on a Post-it and stuck it to the fridge. Then I opened my laptop and scrolled to my banking app. The recurring transfer I’d been sending my parents every month blinked blue. I didn’t blink. I canceled it. No speech. No exit interview. Just a thumb and a new balance.

Christmas morning, I basted with a vengeance, folded napkins with spite origami never intended, cooked enough for an army by hand because revenge, it turns out, is labor-intensive. The doorbell became a drum. People arrived with wine and hugs that lasted a second too long. They told my son what I already knew: we’re proud of you. They said the word doctor like it meant man who keeps the world from breaking and not ranking. He smiled for real.

The phone rang. Mom.

“What did you do?” she snapped. “We made dinner for eighteen. Two showed up.”

“Plenty of leftovers,” I said. “Make sandwiches.”

“You told them we uninvited him!”

“You did uninvite him.”

“That’s not how we meant it.”

“You said there wasn’t room.”

“There wasn’t. Not for—”

“Not for a loser?” I asked. “Not for someone who chose peace over a ranking?”

Silence. Then: “You’re ruining this family.”

I laughed, small and tired. “No. I’m just finally speaking at a volume you can hear.”

I hung up. Not a slam. A click. A door that fits the frame.

Inside, someone was refilling wine. Someone was losing at a board game. My son was laughing with the woman who had babysat him when he was six. He looked okay. For once, so did I.

After the last guest left and the stove surrendered its last smear of gravy, the house went quiet—the good kind. Upstairs, my son paced and spoke in low tones. I don’t know what he said or to whom. I didn’t need to. The wound would scar, not fester. Downstairs, I made tea and felt a peace I hadn’t known I could curate.

Three days later, my mother posted in the extended family chat—the one where forwarded prayers pretend intimacy. A photo of an empty table. “Some people don’t understand what it means to ruin Christmas. I hope they’re proud of themselves.” I didn’t argue. I posted three things:

A screenshot of the meme.

A line: “Losers aren’t welcome for Christmas.”—Dad, on speaker.

Just so we’re clear: my son was never welcome. That was their choice.

I put my phone down and poured more tea. Support filled my inbox—quiet, not performative. Nothing from my parents. Silence is sometimes respect’s imposter. This was not that.

Two weeks later, they knocked. No warning. They stood on my porch like people dropping by to borrow sugar. “We thought it was time to talk,” my mother said.

“About what?” I asked.

My father’s chin lifted. “You’re ruining this family over nothing.”

There it was, clean as a lab bench. “You excluded my son from a holiday about belonging and laughed,” I said. “There’s the something.”

“We didn’t think it would be taken so seriously,” she offered.

“Then you shouldn’t have said it,” I said, and closed the door. Not a slam. A final.

That should be the end. But families are syndicates; they send emissaries. Three days later, my nephew arrived in an expensive coat and a posture he hoped would read as contrite.

“I didn’t mean for it to blow up,” he said. “It was a joke.”

“If it was obvious, you wouldn’t be here,” I said.

He shifted. “They were helping me financially,” he blurted. “If you cut them off—”

I blinked. “You mean the money I sent them—the help I thought was keeping them afloat—went to you?”

He didn’t answer. He didn’t have to.

“You didn’t ask for it,” I said. “But you spent it. And you spent the rest of your credibility trying to buy laughs on my kid’s back. Leave.” He started a sorry. I closed the door.

Then I sat on the floor with the laundry basket I’d been carrying when my parents first arrived and folded towels in a house that was finally mine in practice, not just deed.

This is the part where I used to say I felt guilty. I didn’t. I felt done.

Part II

I have spent my life writing versions of a CV—bullet points of compliance packaged as achievements. My mother would read mine and suggest rearrangements. Lead with prestige. Minimize the local. My father would add verbs you can measure. Published. Presented. Ranked. It took forty-one years for me to write one line they would never approve: Canceled monthly support.

I didn’t tell them. The transfer simply stopped. When a bill you never saw doesn’t get paid, the first person to call is never the one you owe. It’s the one who shamed you into paying it. Silence followed. In its place, a new noise: the sound of money not leaving my account. I bought a new kettle. I booked the roof repair. I breathed.

My son and I built a two-person ritual, an antidote to tradition. Sunday pancakes, no agenda. Talk, if you want. Don’t, if you don’t. He talked about anatomy like a person talks about a new friend—toes to clavicle, the kindness of knees. “The body is so earnest,” he said. “It tries so hard to keep you alive.” He said it like a prayer, which is what medicine is when you strip the human away.

He asked me once, gently, “Do you regret not telling me sooner?” He meant about them, about how the family that taught me to worship the name on the building could never see the person inside one. I said yes because yes was the only response that did not steal his dignity a second time. Then he nodded and returned to his flashcards. That’s the grace adult children sometimes give parents who have finally learned to stop performing.

News of the other nephew—the golden one—arrived the way all gossip arrives, wrapped in concern. He’d dropped out of the prestigious law program. Disciplinary issues, someone whispered, vague enough to be unprovable, sharp enough to be believable. He was applying to a local school to finish “something.” Not the one my son attended—apparently even he wouldn’t dare. Lower ranking. Fewer photos in the family chat.

One evening, my brother texted from a number I hadn’t saved because I was protecting my peace like a cheap insurance plan. Mom and Dad are upset. You need to fix this. He wrote like a man who had never learned that women end up being the custodian of feelings men produce and refuse to clean up.

There’s nothing to fix, I typed. They excluded my son and I declined to reward it.

Stop being dramatic. He added a laughing emoji like it was punctuation. I put my phone face down and felt for the first time the calm of a boundary that didn’t wobble. I used to shake after these exchanges, adrenaline buzzing like hornets. Now I washed the dishes and watched the bubbles pop.

The greatest rewrite I accomplished that winter was not on our family tree. It was on a story about money. Sending that monthly transfer had been my way of paying tuition to a school I had already graduated from: How to Earn Love from People Who Did Not Do The Work to Give It. I canceled my enrollment. The school sent no alumni newsletter. It did not notice my absence. That’s the first freedom and the saddest.

I did tell one person. My son. Not the number. The symbolism. “You don’t have to carry this,” he said, voice low, a man who knows the difference between sympathy and agency. “But I’m proud you did when you thought you should.” I didn’t need permission. I appreciated the acknowledgement that the story wasn’t just gullible daughter finally wakes up. It was woman who made choices with the best information she had, then gathered better information and made new ones.

My parents tried one last tone—reasonable. A printed card arrived, the kind you send when you’ve never texted a sincere sentence in your life. Snowflakes on the front. Inside, two lines: Let’s not make this worse. We can talk if you apologize. I laughed. Not mean. Not bitter. Like a person who had just found the joke at the end of a long, serious lecture. I recycled the card and kept the envelope—for the address I might need one day for something else, like a certified copy of forgiveness.

At work, I watched interns in their best blazers talk politely about grad school. I didn’t tell them not to go. I asked them how they planned to pay for it and whether they could still recognize their life on the other side. Some blinked, surprised to be asked what the brochure doesn’t. Some wrote notes. Some smiled sadly and said their parents would handle it. I hope they meant that as mercy, not control.

My brother’s wife came by one afternoon with cookies and guilt. “I didn’t know,” she said. “I mean—I suspected. But I didn’t know they would use your help like that.” Her face did that thing faces do when they realize their silence made someone else’s sentence longer. I told her she didn’t owe me a confession. She cried anyway. Then she laughed at herself and ate a cookie and told me that our family is a factory that manufactures quiet and calls it maturity. We drank coffee and gossiped about reality TV like it was a sacrament.

In March, my son got his first interview for a summer rotation. He rehearsed with me, standing in our kitchen, answering questions like a man building a bridge: precise, kind, steady. “Why Crestwell?” I asked, playing devil’s advocate. He smiled. “Because when I weigh debt against the thrill of a name, I choose to be a present doctor later rather than an absent debtor now.” He got the spot. He did not post about it. He doesn’t feed trolls.

I wish the story ended with a holiday and a porch light. It ends on a Wednesday with laundry. I was folding towels when the doorbell rang. I expected a package. It was them again—my parents, the same brittle smiles, the same performance. “This is ridiculous,” my father said. “Family forgives.” The way he said it made forgiveness sound like labor only I should perform. My mother said, “We miss you,” like a line she’d practiced in front of the mirror. I said, “I wish you well,” and I meant it like a doctor telling a patient the truth gently: Your habits are not good for you. I cannot cure you. Please stop smoking. I closed the door.

You don’t clap when you close a door. You go back to towels.

The towel I folded next had been a wedding gift twenty years ago. I thought about the register—the aggressive optimism of it. I never asked for forgiveness towels. Maybe I should have. Maybe the store should sell a set: Two bath, two hand, two face, one embroidered with “No.” If you’re wondering whether that line feels petty, congratulations, you’ve never been a daughter in a family like mine.

Sometimes I think about my father’s like under that meme. It is the simplest action the internet offers: approval boiled to a thumb. He didn’t write a caption. He didn’t defend it. He just tapped. That’s the problem, and the answer. Some people think decency is something you perform publicly after you’ve practiced contempt privately. I’m done grading on a curve.

Part III

Pull apart any family tradition and you’ll find it’s built from three things: food, furniture, and power. My mother’s Christmas is a museum where she is both docent and exhibit. There were rules about tree height (tall), ornament placement (curated), candles (unscented only), and table settings (bone china, never the daily). We were an academic family; she gave footnotes to the menu. The roast recipe is adapted from a 1984 Bon Appétit. She said it like she cited sources for an argument I hadn’t realized we were having.

When I hijacked Christmas—the big one, the story people will tell in whispers—it wasn’t because I needed to win a holiday. It was because my son needed a table. The one at my mother’s house had become a courtroom without due process. My father’s like under that meme—that was a ruling.

I bought extra folding chairs as if preparing for a trial and sent a text that read like a summons to kindness. The thirteen who showed up carried covered dishes like evidence. They hugged my son as though he’d been acquitted of something none of us could quite name.

This is what you discover when you make your own version of a holiday: you trade polish for presence. Napkins misfold, gravy skims, a child spills cranberry on a shirt you can’t rescue, and no one dies. Or rather, the only thing that dies is the performance. You resurrect joy from the stovetop like a burnt offering you pretend planned.

People brought stories. “Remember when your volcano exploded at the science fair and the janitor laughed before he cleaned it up?” “Remember when you fixed the leaky sink with duct tape and your grandfather said that wasn’t ‘real’ plumbing?” (We do, and we know now he meant real like prestige.) “Remember when you took apart the radio and made it worse but better somehow?” They said doctor as a verb, not a job.

The night’s soundtrack was clinks and low laughter and the sound of my son finishing a sentence without being interrupted by opinion disguised as concern. I watched his face and saw exactly what he needed. Not a degree. Not a ranking. A room where his decision wasn’t a provocation.

After the last guest left, I stood at the sink and thought about archaeology. Somewhere, a future historian will dig up a family like mine and label the layers: expectation under silence under photo op under resentment. They’ll hold up a meme about vibes and wonder what the hell we were thinking when we confused education with merit and merit with trance.

The post my mother made in the extended family chat was not an accident. It was a flare. She wanted kindling. She got water. People DM’d me to say they were relieved someone had broken the glass. We didn’t know is always a double-edged phrase. It means you didn’t tell them. It means they didn’t look.

My aunt (the one who isn’t my aunt, but earned the title with casseroles) called the next morning. “Proud of you,” she said. “Prouder of him.” Then she said something my mother would have scoffed at: “Prestige is a story you buy when you can’t afford self-respect.” I wrote it down on a Post-it and stuck it to the fridge next to 13.

The knock-and-door cycles that followed didn’t change anything. There is a part of me that recognizes their script because I co-wrote earlier drafts. Let’s not make this worse is a sentence that always translates to Return to silence. Apologize meant absolve us. Family forgives meant you perform labor. I am too old and too tired to apply for a job at a company that keeps rebranding cruelty as culture.

I told myself I would not talk about money again. Then my nephew blurted the truth on my stoop, and money became plot. The dollars I sent my parents were not buying heat or a modest balance of groceries or a new pair of shoes for my mother because she refused to spend on herself. They were buying law school across the country for a boy who thought my son’s school was a punchline. Money is always a narrator; it just speaks after the scene is over. Mine said: they thought your sacrifice was a resource.

I did the pettiest thing I will confess in a church: I laughed alone in my kitchen like a villain in a Hallmark movie when I heard he’d dropped out. Not for the failure. Not for the expense. For the symmetry. My parents had funded status; status did not keep his transcript from cracking. I tamped my laugh down. I told myself I wasn’t his god. Then I said a quiet prayer anyway—for humility to visit him as a teacher who doesn’t grade on a curve.

Some nights I still open the meme and look at it like a relic: a tiny plastic stethoscope on a toddler’s neck, caption sharp and lazy. It’s the laziest jokes that wound the deepest. You didn’t do the work to hate us properly, I think. You didn’t research. You didn’t even get creative with the slur. I close the image and go to the kitchen and wash dishes, because that’s what the living do when they refuse to be haunted.

In April, my son got a second interview. The email subject line—INTERVIEW CONFIRMATION—glowed on his phone like a flare that means land. He looked at me and I looked at him and I didn’t say I told you or They were wrong. I said What tie? We picked the simple one. He wore it. He came home with a small, careful smile. “It went well,” he said, and then, first time in months, asked what do you need from the store. He bought milk and strawberries and the cheap cookies that taste like childhood and we ate them while scrolling pictures of lungs on his tablet. He showed me a bronchus like a man shows his mother a bouquet.

Sometimes I imagine going back to my parents’ house next Christmas and doing something cinematic. Standing at the head of their table and delivering a speech about love and debt and names and ending with my son like it’s a closing argument that will rearrange furniture. Then I remember who they are, and that speeches are what you write when you still believe the audience wants to be moved. I am out of audiences. I am full of rooms.

I did go back once—when it snowed heavy enough that you text neighbors you don’t like just to say the hill is treacherous. I texted: Roads are bad. Be careful. My mother sent back a snowflake emoji. My father sent nothing. I didn’t need proof of receipt. I just needed to know I didn’t let resentment make me into the kind of person I didn’t recognize in the mirror.

Prestige is a good coat. It keeps you warm when people admire it. It’s hell in the rain. The day I chose to buy a cheaper coat that fits instead of the expensive one that chokes is the day I walked into my kitchen and felt it become a church. Not the kind with pews. The kind with bread and light.

Part IV

Taxes force you to narrate your year in numbers. I sat at the table in March with a stack of forms and a laptop, and for the first time in a long time I didn’t have to include gifts to parents in a line that always made me feel like I was explaining my choices to an auditor who would never love me. I thought that would feel triumphant. It felt quiet. Like a lake that stopped trying to act like the ocean.

I audited other parts of my life, too. The group chats: mute on the big one, leave on the minor leagues of obligation. The photos: albums full of smiles we built on scaffolding made from silence. I didn’t delete. I moved them to a folder named Archive so I could excavate later if I wanted to. The house: I rearranged the living room so the couch no longer faced a TV like a pulpit, but the window like a horizon.

My son started his rotation. He texted me dumb photos from the hospital (never anything inappropriate; he’s good) and stories told so carefully no one could be identified. A man thankful for the blanket more than the morphine. A child brave until the Band-Aid peeled. A nurse who swore like a saint when the IV finally cooperated. He came home tired and kinder. He slept like someone whose body wasn’t fighting itself.

I bought a new set of dishes. My mother would call them everyday and say the word like it’s a slur. They are matte, heavy, forgiving. They don’t chip when you look at them wrong. I invited friends to break bread without planning the seating chart like a war map. We spilled. We laughed. We used paper towels instead of cloth napkins and, for dessert, the cheap cookies again. (If there is a brand loyalty program for nostalgia, I’m owed points.)

A letter arrived in May with a seal: Estate Planning Update. My parents were doing their paperwork. The note enclosed was perfunctory. We thought you should have a copy. My name was there, not crossed out (mercies are sometimes administrative). I scanned the lines—hard assets, soft assets, language about fairness that means nothing until it lands in a bank account. I put the packet in the Archive. If you have ever been appointed executor of someone else’s dreams, you know how heavy a sheet of paper can be.

Jo—my friend from the dark years, the one who texts drink water and tell him no with equal frequency—took me out to dinner to celebrate my son’s first successful month. She’s the kind of person who orders for the table and remembers the waiter’s name. Halfway through the second course she said, “You know this is not about prestige. It’s about control.”

“I know,” I said.

“Do you?” she asked, and smiled like a person who knows you did the work.

I did. I do. Prestige is the story you tell yourself about why a person must do what you want. Control is the thing you crave when the person refuses. My parents had turned my son’s decision into an affront because it meant their theory of the world wasn’t universal anymore. That’s not a small grief. I could empathize without excusing.

In June, my nephew messaged me. Not the meme boy. The other one—the second cousin who always sat at the kids’ table with a book and a secret. Heard the Christmas story, he wrote. Glad you did it. We traded catch-ups and links to dumb videos. He said something that stuck: “At some point I realized our family argues like it’s a team sport and never keeps score honestly.” I wrote it on another Post-it and stuck it next to the 13 which, by then, had become a charm against cowardice.

At the hospital gift shop, I bought my son a pin—a tiny caduceus, tacky, perfect. I left it on his desk with a note: Wear it when you feel like a kid with a plastic stethoscope. He rolled his eyes when he found it and wore it anyway for a day, hidden inside his coat like a childish hope that keeps you going.

One afternoon I found myself standing in front of the expensive university my parents would have killed to see on his sweatshirt. I was early for a meeting, so I walked the quad. The buildings were stone and smug. The students were young and winter-paled and hurting in all the ways I used to glamorize. I didn’t feel envy. I felt relief. Like stepping into a museum of a war you survived.

I have learned to spot prestige’s engineers. The mother in the café telling her daughter loudly which internships “count.” The father at the bookstore explaining to a bored son that only certain kinds of knowledge pay. They look tired even when they look proud. I want to put a hand on their shoulders and whisper you can stop. I don’t. We all find our own exits.

When summer came, my parents tried one more time. A family friend was ill; there would be a gathering. It would be nice if you came. I went. Grief suspends the usual rules. My parents were civil. My mother wore sorrow like architecture. My father hugged me like a man hugging a niece, not a daughter—a formality without the muscle memory. I didn’t stay long. I drove home with the windows down and let the air wash off the diplomacy.

On my porch that night, I sat with a glass of water and watched the street. The neighbor’s kid fell off his bike and didn’t cry. A couple walked a dog that didn’t need walking. The sky gave up on sunset and became simply dark. I thought about Christmas again, not like a battle, but like a surgery. We removed something that was killing us. It hurt. We lived.

There is a story people tell about no-contact. That it is cold. Sometimes it is. Sometimes it is the warmest thing you can do for yourself and for the other people who will never learn to stop burning you otherwise. I am not angry in the way that needs a stage. I am angry in the way that cooks dinner and waters plants and moves on.

My son starts his second year in a month. He is applying for more rotations. His classmate—the one who wears expensive shoes and says Crestwell like it’s a disease—asked my son a question in the hallway last week. Why here? My son said what he told me in my kitchen: Because I want to be present later more than I want to be applauded now. The classmate didn’t clap. He nodded. Sometimes that’s how you win a small war.

I used to end every year writing goals. This year I wrote one: Choose sufficiency without apology. Then I printed it and taped it inside the cabinet where the mugs live. Every morning when I grab a cup, I see it. The cheap cookies live on the shelf below. Mercy above, sweetness below. It’s an altar.

Part V

The next December approached like a test I hadn’t studied for because the questions were already tattooed on my bones. My son’s schedule was bricked with exams; he told me not to plan around him. I did anyway. I planned a dinner for twelve—not a rebellion this time, not a rescue either. An ordinary meal for the people who had proven we were their people, too.

A week before the day, an email from my mother arrived. We’ve reconsidered. There is room for him this year. She used his name like a concession. Not your son. Not our grandson. Just the syllables, printed like a library card. I showed my son the email. He read it without flinching and handed my phone back. “We’re good here,” he said. That was that.

But I did one small, unglamorous thing. I replied: Thank you for the invitation. We already have plans. Wishing you a peaceful holiday. Then I put my phone face down and made pastry dough. Boundaries are not drama. They are pie crusts—chill them and they hold shape.

The day arrived cloudy and generous. People filtered in with homemade things and store-bought things and apologies for the latter I refused to accept. My son arrived late, hair damp from a shower taken between study sessions. He kissed my cheek and said smells good like a sacrament. He washed his hands and set the table without being asked because love is learned in small chores.

We played music low. We told the same stories in new ways. We took a picture—a messy, honest version—with two people blocked by a lamp and a child mid-blink. I printed it and taped it to the fridge next to 13 and Choose sufficiency. I made room by removing a magnet from a dentist none of us use anymore.

Midway through dessert, my phone lit. I didn’t have to look to know who it was. I looked anyway. Mom. I let it go to voicemail. A minute later, a text: We’re sorry about last year. We’d like to start over. My son saw the screen. He met my eyes. We are past the age where the parent hides the choice from the child to spare them the moral math.

“What do you want to do?” he asked.

“Finish dessert,” I said. We did. After, I sent a reply. Thank you for the message. Starting over means not pretending nothing happened. It means not ranking people to keep yourselves comfortable. If you can do that, I can meet you for coffee in January. I hit send. Then I turned my phone off and put it in a drawer—the kind of boundary you can do with your thumbs.

Coffee in January happened. My mother chose a café near the university she wishes my son attended. She arrived in the coat she saves for when she wants to look like she invented taste. I wore a sweater and a face I didn’t need to rehearse. We ordered drinks. She stirred hers like she could spin sugar back into time.

“I’m sorry,” she said. The words sounded new in her mouth, like shoes she wasn’t sure fit. “We were unkind.”

“You were cruel,” I said, not to punish. To put the floor under our chairs.

She nodded, small. “We thought we were protecting you from settling.”

“You were protecting your story,” I said. “At the expense of ours.”

Silence that wasn’t war followed. She lifted her cup. “He’s going to be a good doctor,” she said. “He always was good at science.” It was not the apology I wanted. It was the only one she could manage. I took it like a person takes a tiny vitamin—something that might help if you believe in it enough.

“I don’t want a scene next Christmas,” she added, like a dean mediating undergraduates.

“Then don’t write one,” I said.

We sat ten more minutes talking about weather and a mutual friend’s new hip. At the door, we did not hug. We didn’t need to sell the moment. We parted like people who had passed each other on a narrow staircase and chosen not to bump shoulders.

On the way home, I stopped at the hospital where my son was finishing a shift. I waited in the lobby under harsh lights and watched a toddler wear a paper mask like a crown. My son walked out with the posture he’s growing into—taller, the weight of other people’s pain on him like a cape he’s learning how to arrange. I handed him a coffee. He took it, grinned, and did not ask about my meeting. That is how you know you nailed a boundary: the person you love doesn’t feel obligated to help you hold it.

We drove home in that rare winter twilight that makes even strip malls look cinematic. At a red light he said, “I know you met her. Thank you for not inviting me into it.” I nodded, kept my eyes on the traffic, and said, “Thank you for trusting me not to.” We don’t do speeches. We do green lights.

I wish I could give you a finale where my father stands and gives a toast to humility. He didn’t. He sent a short email in February: We will try. Three words. The word try carries the weight of both failure and effort. I printed it and taped it inside a notebook, not because I want to worship it, but because I want to remember the day an old dog considered a new trick.

In spring, my nephew—the meme one—sent a DM. I was a jerk. Sorry. A sentence crafted by someone who has been to court with himself and lost just enough to be interesting. I didn’t reply. Not because I wanted to punish him, but because I am not his teacher. He can pass or fail without me.

When my son matched for a summer placement he wanted, we celebrated with takeout and a movie where nothing much happens except that people learn to live with themselves. He fell asleep halfway through, head on the arm of the couch, sock half-off. I covered him with a blanket like he was five. I sat there until the credits rolled, crying the gentle kind that doesn’t flood, and felt a peace I had not paid for with performance.

Clear ending? As clear as human endings get.

My parents called my son a loser and banished him from Christmas because he refused to make their story his. I gathered our people and made a table that would hold him. I canceled a transfer that once felt like love. I closed a door and opened a room. A year later, I drank coffee with a woman trying to learn a new word and texted a boundary with a period, not an exclamation point.

My son chose sufficiency without apology and taught me how to follow.

This is the part where the YouTube channel asks: Was I too petty rerouting the guest list? Petty is revenge disguised as a party. What we threw was a rescue. We did not move chairs to punish. We moved them to include. If that’s petty, then pettiness is another word for mercy when the people in charge forget how to set places.

The porch light is on. The table is smaller this year. The food is worse, if you measure by magazines. The laughter is better, if you measure by heart. The meme is still out there somewhere with its stupid caption. So is my father’s like. But my son’s hands—steady, careful, learned—are real. He will put them on people who need them. They will not ask where he went to school. They will ask does it hurt and can you help. He will say yes.

That’s the only ranking I care about now.

THE END

News

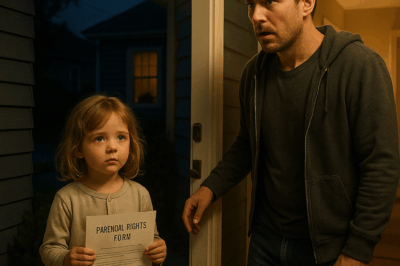

My 4 year old Niece showed up at midnight with a parental rights form CH2

The Knock at 12:03 When the knock came, I thought it was a branch on the siding. The mountain does…

My Husband Kicked Me in Front of His Friends—And My Revenge Was Not What They Expected CH2

By the time the elevator eased open on the executive floor, the building had learned to be quiet around me….

The comedy star who impersonated a White House official has the Internet abuzz with the rumors she spreads along with it CH2

In the high-stakes world of politics, where every statement is analyzed and every public appearance is scrutinized, moments of levity…

My Brother Broke My Ribs—Parents Said ‘Stay Quiet’ But My Doctor Refused… CH2

The Match and the Crack I didn’t mean the joke to land like that. “I’ll get them next time,” I’d…

Fox & Friends: Brian Kilmeade’s ’69’ Flub Has Cohosts Cracking Up CH2

In a recent episode of the popular morning show “Fox & Friends,” host Brian Kilmeade found himself in a light-hearted…

My Son Sent Me A Box Of Cookies For My Birthday, But I Gave Them To His MIL Then… CH2

The Box on the Counter The first time the phone rang, I thought the call had dropped.It hadn’t. “You gave…

End of content

No more pages to load