Part I

John Kepler had always believed his brother’s daughter was safe.

He’d told himself that after Robert’s funeral. He’d told himself again when Ruby—the widow with a sharp tongue and a colder smile—pushed the family away. They’ll be fine. She’ll manage. Nancy’s strong. Ruby won’t let her daughter suffer.

But lies are easy to believe when the truth is unbearable.

That October evening, the truth stepped barefoot onto Ruby’s front porch.

John had only stopped by on a whim. He told himself he was just driving past his brother’s old house, making sure the gutters weren’t sagging, the lawn not completely gone to weeds. It had been a year since Robert’s accident, but grief had no calendar. Sometimes John just needed to see the place where his brother had laughed, shouted at football games, and made pancakes shaped like dogs and cats for his little girl.

He didn’t expect to see Nancy standing barefoot in the cold, her thin arms wrapped around herself.

“Uncle John,” she whispered, like she wasn’t sure she was allowed to say his name.

The sight of her hollow cheeks and the bruise blooming under her sleeve punched the air from his lungs.

“What are you doing out here, sweetheart?”

She shifted on her bare feet. “Mom’s not home. I was just… waiting.”

“For what?”

Nancy’s eyes flicked to the street, then down. “I’m hungry.”

John’s heart twisted. He pulled out his wallet, handed her a twenty. “Get yourself some food.”

She hesitated before taking it, eyes wide with something between shame and gratitude. “Thank you.”

The relief on her face as she clutched the bill was worse than any bruise. Kids weren’t supposed to look relieved over bread money.

Back in his truck, John sat with his keys in his lap, watching the windows of the house that had once been Robert’s. They stared back at him, blank and unblinking. He thought about promises he and Robert had made as boys: If anything ever happens, we look out for each other’s families.

He thought about the last conversation he’d had with Robert—his brother had confessed fears about Ruby’s drinking, about Nancy’s slipping grades, about the constant tension at home. “I’ll handle it,” Robert had said. “Don’t worry.”

But Robert was gone. And now his little girl was begging for food on her own porch.

John whispered into the cab, “I failed you, brother.”

Instead of going to work, John drove to Woodland Cemetery. He found Robert’s headstone—beloved father and brother—and sat down in the damp grass.

“I’m sorry, Rob,” he said, voice breaking. “She’s suffering. She’s starving. Ruby’s killing your little girl, slow and quiet. And I don’t know how to fix it.”

The wind pushed through the trees. The headstone offered no answers. But John’s chest filled with something he hadn’t felt since the funeral: resolve.

“I won’t fail her again. I don’t know how yet, but I’ll get her out of there. I’ll save her.”

It wasn’t a prayer. It was a promise.

A week later, John returned to the neighborhood. He parked three houses down from Ruby’s and found Mrs. Eleanor Flannry watering her petunias. She’d lived across from Robert for fifteen years and had baked cookies for Nancy’s birthdays.

“John Kepler,” she said, squinting. “Haven’t seen you since the funeral. What brings you back?”

“I was hoping to see Nancy.”

Mrs. Flannry’s expression tightened. “Ruby keeps odd hours.”

“Odd how?”

She hesitated, then turned off her hose. “I don’t like to gossip. But… I see things from my kitchen window. That little girl walks around at all hours. Barefoot sometimes. Not dressed for the weather. I’ve seen her at the convenience store asking strangers for food.”

John’s pulse quickened. “She begs?”

“Last week, I saw her digging through Murphy’s Market dumpster.”

The words landed like a hammer.

Mrs. Flannry looked down the street toward Ruby’s house. “That’s not grief, John. That’s neglect.”

She told him about absences at school, excuses Ruby gave, the shouting at night, the times Nancy sat outside in pajamas for hours. “Locked out,” she whispered. “I think Ruby locks her out.”

John clenched his fists. “Have you called anyone?”

“I thought about it. But what would I tell them? That I see a thin child? That I hear shouting? Ruby would deny everything. And Nancy would suffer worse for it.”

“You’re not a coward,” John told her when she admitted her fear. “You’re smart. Ruby would make your life hell if you crossed her.”

“Maybe. But that girl is skin and bones. Someone has to do something.”

She squeezed his hand across the fence. “If you need me to testify, I will. I may be old, but I’m not dead. And I’ll be damned if I let that child suffer while I sit here watering flowers.”

For the first time in a year, John felt hope.

That hope was tested sooner than expected.

One night, John’s phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number:

Uncle John, it’s Nancy. I’m scared. Can you help me?

His heart stopped.

Where are you?

Outside the 7-Eleven on Maple. Mom locked me out again.

John was already in his truck.

He found her huddled against the brick wall, shivering in clothes too thin for the October night. Her bare feet were red from the cold.

She tried to smile when she saw him. “I didn’t know who else to call.”

“You did the right thing.”

He wrapped his work jacket around her shoulders. It swallowed her frame. He bought her sandwiches and chocolate milk from the store, glaring down the clerk who opened his mouth about the “no shoes” policy.

In the truck, with the heater running, Nancy ate like she hadn’t seen real food in weeks.

“How often does your mom lock you out?” John asked gently.

Nancy chewed slowly. “When I do something wrong. When I’m too loud. Make a mess. Forget chores.”

“How often?”

“Once a week. Sometimes more. One time… two days.”

John gripped the steering wheel until his knuckles went white. “Two days? Outside?”

She nodded like it was nothing. “Mrs. Patterson gave me crackers. It was summer, so it wasn’t cold.”

“Sweetheart, that’s not normal. No child deserves that.”

Nancy’s lip trembled. “Mom says I deserve it. She says I’m difficult. I eat too much. Ask too many questions. Cost too much when I get sick.”

“You’re not difficult. You’re twelve. Twelve-year-old girls are supposed to eat, grow, ask questions.”

“But Mom says—”

“Your mom is wrong.”

Her eyes filled with tears. “Do you think Dad would be disappointed in me? For being so much trouble?”

John’s chest ached. “No, baby. He’d be furious with your mom. He’d be proud of you for being strong.”

Nancy whispered, “Sometimes I forget what his voice sounded like.”

John smiled through his own tears. “I remember. He used to tuck you in and say, ‘Sweet dreams, little bird.’”

Nancy’s face lit up faintly. “I remember that. He called me little bird.”

“You were his little bird. And he’d want you safe.”

She fell asleep against his shoulder, finally peaceful.

John looked down at her fragile frame and made another vow.

I’m going to fix this, Robert. Whatever it takes.

Part II

By the time Nancy stirred awake in the truck’s passenger seat, the night had settled into a hush that made even the heater sound loud. She blinked, then sat up fast, alarmed. “Where are we?”

“Somewhere you can get a real dinner,” John said, nodding at the golden arches glowing across the lot. “What sounds good?”

“I can’t,” she blurted. “Mom will smell it on me. She’ll know I ate without permission.”

“You have my permission,” he said gently. “I’ll talk to your mom.”

Nancy swallowed, the old fear tightening her voice. “She’ll be mad. She’ll say I made her look bad.”

“You’re not responsible for your mother’s reputation,” he said, choosing each word like a key. “You’re responsible for being twelve. That’s it.”

Inside the restaurant she ordered like she was defusing a bomb—small fries, a kid’s burger, the tiniest soda. John ordered a second burger and an apple pie and slid them onto her tray. She ate slowly, reverently, as if each bite might be the last before famine returned. Halfway through, she wrapped what remained of the first burger in napkins.

“For later?” John asked.

“In case,” she said.

“You shouldn’t have to plan to be hungry,” he said. “Not anymore.”

Back in the truck, Nancy hugged his jacket around her. John’s phone buzzed. RUBY lit the screen.

If you have my daughter, bring her home. We need to talk.

He stared a moment, then typed.

She’s safe. That’s more than I can say with you.

Bring her home or I call the police. I’ll report you for kidnapping.

His jaw set. He glanced at the girl beside him, still worrying a corner of the napkin like a nervous bird picking straw.

I’ll bring her home in an hour. She was starving when I found her.

A long pause. Then:

Don’t believe everything she tells you. She’s been lying for attention.

John deleted the message without replying. He looked at Nancy. “If you ever need me again, you call. Sneak to a neighbor. Ask a cashier. Use a school phone. Any way you can.”

“I… Mom took my phone,” she said. “Because I used it too much.”

John fished a card from his wallet and pressed it into her palm with a twenty folded beneath. “Work number on top, home number below. Keep them. Use them.”

She tucked the card somewhere secret inside his jacket. “Okay.”

He drove Nancy home an hour later, idled at the curb. The porch light snapped on. “Do you want me to walk you to the door?” he asked.

“No,” she whispered. “It’ll make her mad.”

“Remember what I said,” he told her. “You are not responsible for her anger.”

Nancy opened the door, then looked back. “Uncle John?”

“Yeah?”

“Sweet dreams,” she whispered, then added, testing the words, “little bird.”

“Sweet dreams, little bird,” he said, and watched her go.

He didn’t drive away. He parked around the corner and walked to Mrs. Flannry’s with a tight, deliberate calm in his steps.

Eleanor Flannry opened her door in a robe, hair in tight white curls, eyes sharp behind thick lenses. “John?”

“I need help,” he said simply. “The kind that requires a notebook and a good view.”

She ushered him in. The living room smelled like lavender sachets and lemon oil. Photos crowded the mantle—Halloween costumes, blurry soccer games, Nancy’s fifth birthday with a lopsided cake.

“I need dates and times. How long Nancy’s outside, what she’s wearing, who comes and goes. Photos if you can do it safely.”

“You’re building a case,” she said, not a question.

“I’m trying to open a door the system keeps closing.”

She lifted her chin. “I’ll watch. I’ll write. I’ll call you when there’s something you need to know.”

“Careful,” he said. “Ruby’s temper—”

“Let her try me,” Mrs. Flannry said. “I’ve survived two husbands and thirty-seven years teaching seventh grade. Nothing on this street scares me more than doing nothing.”

John exhaled. “Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me yet,” she said. “Thank me when the child is safe.”

The call came on a Tuesday at 6:47 a.m. “Uncle John?” The voice was thin, tremoring. “I’m at school. The nurse’s office. Can you come get me?”

He was out the door before answering. “What happened, sweetheart?”

“I threw up in class. The nurse says I have a fever. Mom isn’t picking up.”

He signed Nancy out of Jefferson Elementary twenty minutes later. The nurse, a woman with kind hands and a no-nonsense bun, met him at the door to the small clinic room. “Are you Mr. Kepler?”

“Yes.”

“She’s at 102,” the nurse said, voice lowered. “No fluids in her stomach when she vomited. No food. Mr. Kepler, I’m going to be direct. Is she getting enough to eat at home?”

John’s pulse thudded. “Why do you ask?”

“Because I see kids like this too often. Loose clothes, hair thinning, dizziness. She’s lost significant weight since the start of the year.” She glanced through the small window at Nancy, curled on the cot, blanket up to her chin. “I’m required to document when I suspect neglect.”

He nodded once, feeling something like hope flicker. “You’ll call?”

“We follow protocol,” she said. “But the truth is—sometimes the system is slow. Sometimes it fails. Keep records. Keep being here. It matters more than you think.”

He lifted Nancy from the cot—she weighed almost nothing—and carried her to the truck. “Doctor,” he said. “Now.”

Urgent Care took one look at Nancy and ushered her back. The doctor, a young woman with steady eyes, listened to their answers, listened harder to the things Nancy didn’t say. “We’ll rehydrate with IV fluids,” she said, and the nurses set to work with practiced gentleness.

When they were alone, the doctor motioned John into the hall. “Mr. Kepler, this child is malnourished. I’ll file the report. But you should know: these cases take time. If she has a relative who can keep her safe, that helps.”

“She does,” he said. “Me.”

“Then be ready to show it. Home study. Background check. Documentation.” She held his eyes. “Don’t give up when the process grinds.”

“I won’t,” he said.

Back in the room, Nancy’s cheeks had a little color from fluids. She looked at the needle taped to her forearm like it was a miracle. “Am I in trouble?” she asked.

“For being sick?” John smiled. “Not possible.”

“For telling the doctor I’m hungry,” she whispered.

“There are no wrong answers when a doctor asks how to help you,” he said. “Only the truth.”

Nancy studied his face as if memorizing how it looked when someone meant those words.

After the clinic, John took Nancy to his apartment. He made her a pallet on the couch, tucked her in, left the bedroom door open. He sat at the kitchen table with his laptop open and a legal pad that was suddenly filling with names and numbers: school nurse, urgent care, child protective services. He made calls. He got case numbers, polite voices, cautions about process.

At dusk, Ruby called.

“Where’s my daughter?” Her voice had the thin “reasonable” tone people use when they’re barely holding back a scream.

“With me,” John said. “She was sick. School called. I took her to a doctor.”

“You had no right,” Ruby snapped. “She’s my child.”

“She’s my niece,” he said. “She’s a sick child who needed care.”

“Bring her home. Now.”

“She needs rest. Fluids.”

“Bring. Her. Home.”

“Ruby,” he said, and gentled his voice as if speaking to a skittish horse. “Things are going to change. Nancy will eat. She will be warm. She will be safe.”

“Are you threatening me?”

“I’m promising Nancy,” he said, and hung up before his anger wrote words he couldn’t take back.

He drove Nancy home, watched her square her shoulders at the front door like a soldier stepping into a fight. The door opened; Ruby’s silhouette filled the frame, sleek and composed. John couldn’t hear the words, but he could read the tension. The door shut.

He sat there long enough to know he couldn’t knock it down and take Nancy—yet. Then he drove to the police station.

The desk sergeant—Mike Torres, a linebacker from John’s high school—looked up and sobered. “Kepler. What’s wrong?”

“I need to report child abuse,” John said, voice even.

In a back room that smelled like coffee and old carpet, John told the story straight through. Mike listened, took notes, asked careful questions.

“Have you called CPS?”

“The nurse did. The doctor did. I did.”

“That’s good,” Mike said. “Multiple sources matter.”

“And if it isn’t enough?”

Mike met his eyes. “Then you keep showing up. Document. Be there. Sometimes we catch them. Sometimes a neighbor’s statement tips it. Sometimes a nurse’s chart. Sometimes a lost temper in front of the wrong witness.” He capped his pen. “And sometimes a stubborn uncle who refuses to quit.”

John exhaled. “I can do stubborn.”

“I remember,” Mike said, smiling grimly. “You stiff-armed me into the bleachers junior year.”

“Accident,” John said.

“Don’t make this one,” Mike replied.

The week that followed taught John the shape of a system designed like a series of small doors, each with a different lock. Nurse reports started a file. Doctor’s notes added weight. Police “incident” numbers pinned events to a map. None, alone, moved the hinges.

So he made keys.

Every evening he stopped by Ms. Flannry’s kitchen. She had a notebook open, lines of neat teacher cursive under columns for date, time, weather, clothing, behavior.

“Tuesday,” she read, “outside at 6:50 a.m., pajamas, no shoes, 43 degrees. Shivering. Let in at 8:05.”

“Thursday,” she read another night, “dumpster behind Murphy’s. Took two apples. Hid them in her shirt.”

“She’s getting bolder,” John said softly, proud and wrecked at once.

“She’s getting hungry,” Eleanor corrected.

John went home and added documents to a manila folder that had become a case: urgent care discharge with malnutrition circled; screenshots of bank records his lawyer helped him request showing a life insurance deposit, then car payments, salon debits, boutique charges. School emails noting absences. The nurse’s weight logs: down three pounds, down five, down eight.

Each paper was a tile. He was laying a mosaic that spelled a single word: unsafe.

The call from Eleanor came three days later, her voice tight. “She’s been out since morning, John. Pajamas. No shoes. It’s cold. Six hours.”

John didn’t remember leaving his shop. He only remembered the sight of Nancy on the steps, arms wrapped around herself, lips blue. He knelt and gathered her up without asking. She was so light he could feel each bone.

“What happened, little bird?”

Her eyes slid away. “I… wet the bed.”

He swore softly. “You’re sick. That’s not a crime.”

“She said I had to learn to be a big girl,” Nancy whispered, clavicles like small wings under too-thin skin.

He carried her to the truck, turned the heater full blast, wrapped her in a blanket. When the shivers eased, she said in the smallest voice, “I think… I think I might have done it on purpose.”

John paused. “Why?”

“Because I knew she’d lock me out, and if she locked me out… maybe you’d come.”

He closed his eyes against the burn. “You never have to hurt yourself to get my help. Ever. You call, you run to Mrs. Flannry’s, you ask a cashier, you tell the school. You don’t have to make your mother angry to be seen.”

“What if you get tired of me?” she whispered. “What if I’m too much trouble?”

“Not possible,” he said, and meant it with his whole life.

He took her back to his place, ran a hot shower, found sweatpants that needed six rolls at the cuff and a soft t-shirt that hung like a dress. He made grilled cheese and tomato soup and watched her eat like food was a language she was relearning. Then he called Ruby.

“She’s not coming home tonight,” he said.

“She is,” Ruby snapped. “Or I’m calling the police.”

“Call,” he said. “And bring your explanation for why your twelve-year-old has frostbitten toes.”

Silence. Then a hiss: “She’s a burden. She cost me everything. She looks like him.”

John felt something final settle in his chest. “There it is,” he said. “You said the thing you can’t take back.”

“She needs to toughen up.”

“She needs a mother,” he said, and hung up.

The police came anyway—two officers John didn’t know—soft apologies in their posture. Without fresh bruises and a child claiming fear, they had to return Nancy.

“What about her word?” John asked.

“She says she understands why she was punished,” the taller officer said. “We can’t override a parent absent imminent danger.”

Nancy’s eyes begged him to fix it. He couldn’t. Not like this. Not tonight. The patrol car door shut like a verdict.

He watched Ruby at the door: composed, contrite for the show, hand on Nancy’s shoulder like a brand. The officer said something, Ruby smiled, the door closed.

John sat there with the steering wheel under his hands and the promise in his chest and felt the helplessness crest and break into anger he could use. Then he started the truck and drove, not home, but to the office of a lawyer who owed him a favor.

In the days that followed, the evidence stack grew. Eleanor’s notebook entries thickened. The school nurse added weight charts and notes. John’s lawyer filed motions for information: life-insurance disbursements, utility shutoff warnings that didn’t exist because the bills were current even as the pantry was locked.

All of it built toward one thing John knew he needed and hated himself for waiting on: a visible injury no judge could ignore.

He didn’t have to wait long.

It was a Saturday when Nancy called, voice shaking. “I fell down the stairs,” she said. “My wrist… I can’t move my fingers right.”

“Where is she?” John asked.

“Gone. Store.”

He drove like the road belonged to him and found Nancy on the steps, cradling a swollen wrist, fresh bruises along her forearm like fingerprints.

“Truth,” he said softly. “Did you fall?”

“I asked for breakfast,” she whispered. “She said I’d eaten too much this week. I asked for crackers. She… pushed me. I was at the top of the stairs.”

He swallowed the curse. “Hospital. Now.”

The ER doctor—Dr. Sarah Kim—was calm competence in blue scrubs. X-rays, exam, photos, a nurse’s camera clicking like a metronome. Dr. Kim looked at John in the hall and didn’t sugarcoat it. “This is not a staircase fall,” she said. “These bruises… someone grabbed and shook her. And she’s malnourished.”

She made the mandatory call. She made a second one, too, petitioning for emergency protective custody. “We do it when there’s imminent risk,” she said. “This qualifies.”

Child Protective Services arrived with a detective who had the kind of voice that made people tell the truth. This time Nancy did. She told them about the pantry lock and the long cold hours on the steps, about begging outside stores, about life insurance money that bought hair appointments but not groceries, about the time Ruby pushed her near the stairs. While she spoke, her hands trembled, but her voice didn’t break.

Ruby arrived three hours later in a breathless performance—concerned, harried, wounded by the insult of suspicion. Detective Martinez listened to her story—so much clumsiness, such a picky eater—and then showed her the photos. The mask slipped. Rage flashed. Words came out sharp as glass: He’s trying to steal my daughter. She looks like him. She’s a burden.

They arrested her in the ER corridor for child abuse and endangering the welfare of a minor. As the cuffs clicked, Ruby snarled at John, “She’s mine.”

“She stopped being yours,” John said quietly, “the first time you made her beg for bread.”

Family court on Monday morning smelled like coffee and old carpet, like the police station had. The judge—a woman in her sixties with eyes that didn’t miss much—read the file. Dr. Kim testified, voice steady. Mrs. Rodriguez from the school spoke about weight charts and empty stomachs. Eleanor Flannry’s notes, typed and printed, marked with timestamps and weather, made a stack all their own; her voice, when called, was iron wrapped in lace.

Nancy spoke to the judge in chambers. She came back with her chin up. The child services lawyer stood and said, “She’s expressed a clear preference to live with her uncle. She’s afraid to go home.”

Ruby’s lawyer tried to patch the story—grief, single motherhood, a difficult child—but the tiles in John’s mosaic had finally made their picture. The judge looked over her glasses at Ruby. “I’m granting emergency custody to Mr. Kepler. Supervised visits only, contingent on counseling, parenting classes, and compliance. Assets related to the life-insurance payout are frozen pending review.”

John exhaled for what felt like the first real time in months.

Outside, in the parking lot, Ruby hissed, “This isn’t over. She’s my blood.”

John didn’t raise his voice. “Blood wasn’t the problem,” he said. “Hunger and cold were.”

He left her there and walked to his truck. Nancy sat inside, his jacket swallowing her again, but her eyes were different. Less wild. More tired. More hopeful. He opened the door.

“Are we going to your house?” she asked.

“We’re going home,” he said, and saw the word land like warmth.

“Can we make pancakes?” she said, smiling tentative as dawn. “Like Dad’s?”

“Pancakes,” he said. “Shaped like anything you want.”

“Birds,” she said. “Little ones.”

“Little ones it is,” he replied, and drove them toward a kitchen that would always have flour and eggs and someone to flip the messes with her.

Part III

Nancy’s first night at John’s apartment was quiet in the way storms are quiet after they’ve passed—air heavy, silence holding its breath.

She sat at the small kitchen table, her thin legs swinging, watching him mix pancake batter in a bowl. It was nearly nine o’clock at night, but she’d asked for pancakes, and John wasn’t about to tell her no.

“You ever seen a dog-shaped pancake?” he asked, trying to sound casual.

Her lips twitched. “Dad used to make them. But they never looked like dogs. More like… blobs.”

John smiled. “Well, your dad and I used to compete. He said his blobs had personality. I said mine had ears.”

Nancy’s smile widened just a fraction, and when he slid the first lopsided attempt onto her plate, she actually laughed. Not a polite, practiced chuckle—the laugh of a twelve-year-old who forgot, for a second, that she’d been starving.

She drowned the pancake in syrup, ate half, and wrapped the rest in a napkin.

“You don’t have to save it,” John said gently. “There’s more batter in the bowl. You can have seconds, thirds—heck, the whole stack if you want.”

Her hand froze mid-wrap. Slowly, she unwrapped the napkin and took another bite.

The days that followed felt like waking into a different world—for both of them.

Nancy explored his apartment cautiously, as if she might set off alarms. She asked before opening the fridge. She folded her blanket on the couch each morning, lining the corners with soldierly precision. She whispered “thank you” so often it became a second language.

John tried to undo years of conditioning one reassurance at a time.

“Yes, you can take another glass of milk.”

“No, I won’t get mad if you spill.”

“Yes, the light can stay on at night if you want.”

“No, you don’t have to earn dinner.”

At night, she had nightmares. She’d wake up crying, convinced she was back on Ruby’s porch in the cold. John would sit beside her, hand on her shoulder, and repeat the same promise until she drifted off again:

“You’re safe now, little bird. Nobody’s locking you out again.”

If Nancy’s days were slowly getting brighter, Ruby’s were unraveling fast.

Out on bail, she showed up to supervised visits with a smile stretched so tight it looked painful. She brought Nancy toys still in their plastic, clothes with price tags dangling.

“See how much Mommy loves you?” she’d coo while the social worker took notes.

Nancy would sit stiffly, eyes darting to John for reassurance. When Ruby leaned close and whispered, “Tell them you lied about me and you can come home,” Nancy’s small shoulders would hunch like she was bracing for impact.

The social worker documented everything.

Meanwhile, investigators dug into Ruby’s finances. The $50,000 life insurance payout Robert had left was nearly gone—swallowed by salon visits, luxury clothes, and a car Nancy wasn’t even allowed to ride in.

When questioned, Ruby insisted the money had been spent “responsibly.” But receipts didn’t lie.

Mrs. Rodriguez, the nurse at Jefferson Elementary, became John’s unexpected ally. She called him into her office one afternoon, her expression soft but serious.

“She’s gained four pounds in three weeks,” she said, showing him the chart. “That’s what regular meals do. But…”

John stiffened. “But what?”

“She still flinches when I ask how things are at home. Trauma takes longer to heal than weight. Keep reassuring her. Consistency will matter more than anything.”

John nodded. “She’s been through hell. I just want her to know it’s over.”

Mrs. Rodriguez smiled. “It’s not over yet. But you’re giving her something she hasn’t had in a long time: safety.”

Three months later, they stood in family court again. Ruby’s lawyer argued for reunification, claiming Ruby had completed two parenting classes and a psychological evaluation.

But the evaluation painted her as volatile, self-absorbed, incapable of empathy. The parenting classes had ended with Ruby storming out after a counselor suggested “consequences shouldn’t include starvation.”

Nancy testified again. Her voice shook at first, but steadied as she described nights locked outside, days without meals, the fall down the stairs.

“She told me if I said anything, nobody would believe me,” Nancy said, eyes on the judge. “But Uncle John believed me. He always does.”

The courtroom went still. Even Ruby’s lawyer didn’t try to argue.

The judge ruled: Nancy would remain in John’s custody while the state moved to terminate Ruby’s parental rights.

Ruby exploded in the hallway afterward, hissing at John, “You stole her from me. She’s my blood.”

John didn’t flinch. “You lost her the moment you stopped feeding her.”

At home, Nancy slowly remembered how to be a child.

She asked for bedtime stories. She left her shoes in the middle of the floor. She painted pictures at the kitchen table, smearing more watercolor on her hands than the paper.

She invited Mrs. Flannry over for pancakes one Saturday, proudly flipping them herself. The old woman cried into her tea when Nancy served her a heart-shaped one.

At school, Nancy joined art club. She made friends. She stopped hoarding crackers in her backpack.

But sometimes, she still asked questions that broke John’s heart.

“Uncle John, am I broken?”

“No, little bird. You’re healing.”

“Do you think Dad can see me?”

“Every day. And he’s proud.”

“Will I ever stop having nightmares?”

“Maybe not completely. But you’ll never wake up alone.”

Six months after she moved in, John took Nancy to Woodland Cemetery. She carried a small bouquet of daisies, laid them on Robert’s grave, and whispered, “I love you, Dad.”

John knelt beside her. “Your dad would be so proud of you, sweetheart. For surviving. For telling the truth. For being brave.”

Nancy leaned against him. “Do you think he’s happy I live with you now?”

“I think he’s relieved,” John said softly. “Because he knows you’re safe. And loved.”

She slipped her small hand into his. “Uncle John?”

“Yeah, little bird?”

“Promise me something.”

“Anything.”

“Promise you won’t ever let me go back.”

John squeezed her hand. “I promise. Not while I breathe.”

Nancy smiled—the kind of smile that reached her eyes this time. “Not while I breathe either.”

As they walked back to the truck, Mrs. Flannry waved from her garden. Nancy waved back, hair shining in the sunlight, cheeks full again, eyes bright.

The girl who had once begged for crackers behind a store dumpster was now laughing about pancakes shaped like birds.

Robert’s little bird was safe.

And John had finally kept his promise.

Part IV

The hearing to terminate Ruby’s parental rights drew more people than John expected. Social workers, lawyers, even a few neighbors who had submitted written statements sat in the gallery. Eleanor Flannry arrived in a bright floral dress, her notebook tucked into her oversized purse like a loaded weapon.

Ruby came in last, dressed in a conservative navy suit, her hair pulled back in a bun that looked like it hurt. She carried herself like she was still in control, as if the courtroom were a stage and she was just waiting for her cue. But John noticed the tremor in her hand as she adjusted her papers.

Nancy sat beside John at the table, her small fingers clutching his hand. She had gained weight in the months since she’d been living with him, her hair shinier, her cheeks rounder. But the fear was still there in her eyes when Ruby turned to look at her.

The state’s attorney presented the case:

Medical records documenting malnutrition, bruises, and untreated illnesses.

Testimony from Dr. Kim and the school nurse, both unflinching.

Eleanor Flannry’s meticulous notes: dates, times, temperatures, descriptions.

Then came the bank statements. Tens of thousands of dollars from Robert’s life insurance, drained within a year. Salon visits, designer handbags, vacations with no record of Nancy traveling. Meanwhile, the girl was begging behind convenience stores.

Ruby’s lawyer tried to paint a different picture: a grieving widow overwhelmed by responsibility, doing her best under difficult circumstances. But each piece of evidence chipped away at the mask Ruby wore.

When Nancy spoke, the room stilled.

“She locked me out a lot,” Nancy said softly. “Sometimes all day. Sometimes at night. She said if I told anyone, no one would believe me. But Uncle John did. He believed me.”

Her voice wavered, but she didn’t stop. “I don’t want to live with her anymore. I want to live with him.”

It was the clearest truth in the whole proceeding.

The judge delivered the decision without hesitation.

“Based on the overwhelming evidence of abuse and neglect, this court terminates the parental rights of Ms. Ruby Hail. Custody of the minor child, Nancy Kepler, is granted to her paternal uncle, Mr. John Kepler. All remaining funds from Robert Kepler’s life insurance policy are to be placed in a trust for Nancy’s education and future needs.”

Ruby shot to her feet, face twisted. “You can’t take her from me! She’s mine!”

The bailiff moved between her and the bench as the judge’s gavel cracked like thunder. “Sit down, Ms. Hail.”

Ruby fought, her voice rising. “This is all lies! She’s an ungrateful brat, and he’s poisoning her against me!”

The gavel struck again. “Remove her from the courtroom.”

As deputies guided Ruby out, she turned back, eyes blazing at John. “This isn’t over. I’ll make you pay.”

But the words sounded hollow. For the first time, John saw not a monster but a woman who had built her life on control—and had just lost it all.

Ruby was later convicted of embezzlement and fraud, charges uncovered during the financial investigation. She was sentenced to two years in state prison. She stopped writing letters to Nancy after the first month, when John returned them unopened with a firm message through the caseworker: You’ve lost the privilege.

The trust fund was established, modest but protected. Nancy’s education would be secure.

For John and Nancy, life didn’t transform overnight. Trauma clung to Nancy in small ways. She flinched when someone raised their voice, even in laughter. She still hoarded crackers under her pillow for weeks, until John gently pointed out the fully stocked pantry and promised it would always be that way.

But healing came in increments.

The first time Nancy asked for seconds without apologizing, John nearly cried.

The first time she invited a friend from school over, he bought pizza and soda and watched them giggle on the living room floor until midnight.

The first time she fell asleep on the couch and murmured “Sweet dreams, Uncle John,” he carried her to bed and whispered back, “Sweet dreams, little bird.”

He learned how to pack lunches she actually liked. She taught him how to use TikTok. Together, they learned to be a family.

Six months after the final court ruling, they returned to Woodland Cemetery. Nancy carried fresh daisies, her steps steady as she approached her father’s grave.

She knelt, placing the flowers gently on the stone. “Hi, Dad. Uncle John kept me safe, just like you would have. I live with him now. We make pancakes on Sundays. I even flip them myself, just like you taught me.”

Her voice trembled, but she pressed on. “I still miss you every day. But I think you’d be proud of me. I told the truth. I didn’t let Mom scare me anymore. And I’m okay now. Really.”

John crouched beside her, hand on her shoulder. “He is proud of you. So am I.”

Nancy leaned into him, eyes shining. “Do you think he can see us?”

“I think he sees everything,” John said. “And I think he’s relieved, knowing you’ll never go hungry or cold again.”

Driving home, Nancy asked a question that nearly broke him.

“Uncle John, am I… allowed to be happy now?”

He glanced at her in the passenger seat, the sunlight catching her hair, her cheeks finally filled out, her eyes no longer dulled by hunger.

“Yes, little bird,” he said softly. “You’re more than allowed. You deserve it.”

She smiled—a real, unguarded smile—and leaned her head against the window.

For the first time in a long time, John felt something more powerful than resolve, more lasting than anger. He felt peace.

The girl who once dug through dumpsters for apples now laughed over pancakes shaped like birds.

The man who once sat at his brother’s grave whispering apologies now stood tall, promise kept.

Nancy was safe. She was loved. She was home.

And John Kepler knew, without a shadow of doubt, that Robert was smiling down on them both.

THE END ✅

News

I Cut Off My Family’s Secret Financial Support. They Had No Idea I’d Been Paying Their Bills… CH2

Part I The steakhouse was the kind of place that makes you walk a little straighter, as if the waiters…

My neighbor called, voice tense. “Man, someone’s dril/ling your wife at your house—and the whole neighborhood can hear it.” CH2

Part I My phone rang in the middle of a Friday that had already overstayed its welcome. The stamping press…

Mid-labor, through the pain, I looked up—and froze. The doctor delivering my baby… was my ex. Gritting my teeth, I screamed, ‘Hurry up and pull your son out!’ CH2

Part I There’s a racket the air makes in July when it hits hot pavement and a car with no…

“Reborn, I smiled and said yes—to the man my sister once loved and ruined. She’ll never know what she truly lost.” CH2

Part I The halls at North Ridge High smelled like pencil shavings, old radiators, and cafeteria pizza—exactly the perfume you’d…

AT MY DAUGHTER’S BEACH WEDDING, HER FIANCE SMIRKED, “PAY $50K FOR THIS LUXURY OR VANISH FOREV… CH2

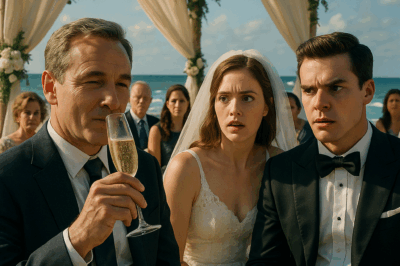

Part I The champagne flute trembled in my hand, but no one noticed. They thought it was nerves, age, maybe…

MY SECURITY COMPANY CALLED ME AT 2 AM. “SIR, THERE’S A BREACH AT YOUR MOUNTAIN CABIN… CH2

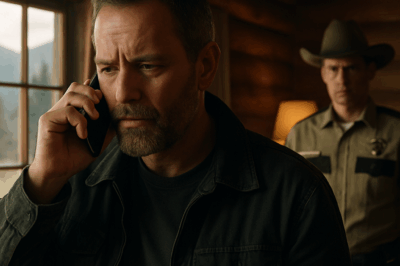

Part I When the phone rang at 2:03 a.m., I thought it was a wrong number, the kind that slips…

End of content

No more pages to load