Part I

My phone rang in the middle of a Friday that had already overstayed its welcome. The stamping press at the factory had been groaning all morning, throwing fits like an old bull with a nail in its hoof, and I had grease ground into the whorls of my fingertips so deep it looked tattooed. When I saw the name on the screen—Darla from next door—I almost let it go to voicemail. Darla never called. She posted. She hovered. She commented on things that didn’t need commentary. But call? Never.

I swiped green anyway. “Yeah?”

Her voice came in breathless, like she’d sprinted to the phone and dialed with her lungs. “Aaron? You need to get home now. Someone’s drilling your wife at your house, and the whole neighborhood can hear.”

Every muscle in me went slack and tight at once. For a stupid second my brain caught on the wrong detail—drilling?—and then I heard the slap of male voices in the background, an electric whine, a clatter, Darla shouting for one of her kids to get out of the street. It registered all at once: not that kind of drilling. Power tools. Truck doors. A stranger’s laugh rattling where I knew exactly how quiet my living room should sound at two in the afternoon.

“What do you mean drilling?” I asked anyway, because some part of me still hoped she meant installing cable, or a broken lock, or a joke so bad I could hang up on it. “Who’s there?”

“Men. A couple of them. And Kayla’s out front with one of them, barking orders.” She lowered her voice to a sharp whisper edged with glee and concern. “They’re hauling your furniture out the door like it’s a going-out-of-business sale. I thought you were moving. But I saw your truck at the plant ten minutes ago when I drove by, so—”

I didn’t hear the rest. The press room, the grit, the ancient wall clock with its tired second hand—gone. I was halfway to the exit before the foreman looked up. “Taylor! Where you—”

“Emergency,” I said, and I must have looked like an emergency because he didn’t argue.

The drive home was eight minutes if you hit all the lights and didn’t mind rolling a stop sign where the oak roots had buckled the asphalt. I did it in five with my heart in my teeth. The closer I got, the more I started tallying what could be taken in that kind of time. The leather armchair I’d saved two years to buy because my dad had always had a chair, a kingdom in brown hide. The oak table my mother said would be “an heirloom if you stop putting greasy elbows on it.” The framed photo of Judy at the county fair, blue ribbon limp in one hand, ice cream melting down the other.

My house—my mother’s house, to be honest, though it was mine to live in as long as anyone could remember—was already a scene when I skidded to the curb. The moving truck yawned at the mouth of the driveway, its ramp a gray tongue. Two guys in matching t-shirts leaned against it, the word BULLDOG MOVERS curled across their chests like a growl. One was thin and bored; the other had arms like a barge and a smile like a dare. The electric whine Darla warned me about buzzed from inside—someone undoing something that had belonged to me yesterday and was now a series of screws and decisions.

I didn’t think. I didn’t weigh my words. I saw a coffee table edge tilt out of my front door in the hands of a stranger and a man I’d never seen, and the air between us narrowed to a wire. I was moving before my mouth caught up.

“Hey!” I shouted, voice snapping the way metal does in winter. “Put that down.”

The stranger—tall, mid-forties, tan in a way that wasn’t native to our county—looked up like I’d been expected and he was both sorry and not. “We’re almost done,” he said, voice easy, and that’s what lit the fuse: easy.

Almost done with my life.

“You’re almost done when I say you’re almost done,” I said, closing the distance in a crackle. “Who the hell are—”

“I’m Walter,” he said, casual as a handshake in a church foyer, and then the table angle shifted and the Bulldog with the arms grunted, “Hey, boss, careful.” Boss, my head repeated, and the word hit the back of my eyes in a hot spray.

“Boss?” I said. The next thing I knew, Walter was backpedaling. A bag of screws spilled somewhere. My hands were on his shirt, a checkered thing that would’ve looked expensive if it hadn’t been crumpled in my fists.

“Hey, man,” he started, palms up, but I didn’t let him finish being reasonable. I pushed him, and his shoes skittered on the ramp. He pinwheeled, slid, and the sound of his shoulder thudding the driveway hit me in the chest. He let out a grunt like something low and hurt.

I don’t remember deciding to be the version of myself that came next. I remember the heat, the animal of it, a life I’d kept caged for seventeen years in a decent job, Sunday chores, lawn stripes straight as a drill sergeant likes them. I remember thinking, You walked into my house and you don’t belong in this air, and then there was the weight of my fist, the sharp report of knuckles meeting cheek, the small, stupid part of me keeping score with the flush of pain in my hand. Another to his shoulder—less precise, more raw, wild as the noise roaring up my throat.

He curled in on himself, covered his face, and somewhere in the near distance I heard a voice that had told me I was handsome once, told me to take out the recycling, told me a hundred domestic nothings over a decade and a half.

“Aaron! What the hell are you doing?” Kayla’s voice. Shredded. Close.

The world did the slow-motion thing that only happens in car accidents and bad dreams. I turned. Kayla was running up the driveway, hair loose, a sunstripe of sweat on her collarbone, eyes wide with a kind of panic I couldn’t read—fear for him, fear of me, fear for the whole tangled ruin we were about to make permanent. She got between us without knowing if I’d stop. I stopped. Reason returned in a hiccup.

She knelt. “Walter,” she said, the name like a confession she hadn’t meant to make here, in front of the two shrugging Bulldogs and the hydrangeas Darla planted too close to our mailbox. “Oh my God, Walter—stay still.” She touched his face like her hands were made of apology.

“Walter?” I said. The name felt wrong in my mouth, like biting tinfoil. “Who’s Walter?”

Kayla flinched. The look she gave me carried seventeen years and exactly zero seconds. “My boyfriend,” she said, and the word hit with the physics of a thrown brick: weight, arc, certainty, the inevitable crash.

Pieces of me rearranged and didn’t fit back together. True story: you can know something is true and still have to learn it twice. The second learning is when it touches your skin, puts blood on your knuckles, asks you to say it out loud. My wife has a boyfriend is a sentence with a thousand ways to be stupid in it, and still I couldn’t find the part that didn’t feel like the desert cracking for rain.

Walter coughed from the pavement. He looked at me, then away, and in the pale curve of his ear I saw a man who would’ve been perfectly boring if I’d met him at the Rotary. In my driveway, he was a target.

“You think you can steal from me in broad daylight?” I heard myself say, like I was someone else trying out lines. I kicked him, not even a wind-up, just a short, sharp decision delivered to a soft place. He folded. Kayla shrieked. The Bulldogs’ faces changed from bored to interested, like the TV had gotten suddenly good.

In the soundscape of my few remaining good choices, a siren tore in and welded itself to the edges of everything. Someone had called, maybe me, maybe not, because in the mess of it I remembered my phone, remembered my angry thumb and the way the numbers looked fat and stupid on the screen when rage was steering. I’d told the operator my name and my address. I’d ignored her ask to wait inside. I’d provided the soundtrack to my own arrest.

The black-and-white slid to a stop angled across the mouth of my driveway like it was a fishing net and we were tuna. Two officers got out, hands loose but ready. The big one put himself between me and Walter, chest like a wall. “Back up, sir,” he said, not shouting because he didn’t need to. Something about the way he held his hand flat at my sternum told me exactly who could escalate and who couldn’t afford to.

I backed up. I let my fists unclench. I told myself not to be the kind of man who became a headline.

“I’m the one who called,” I said, words tasting like tin. “They’re stealing my property.”

The big one didn’t look at me. He looked at Kayla, who was doing her best to look like someone caught out and still sure there was a technicality that might save her. Other cop, wiry and sharp, scanned the scene: the ramp, the scrape mark on the driveway where Walter had made contact, me, the thin thread of blood slipping from Walter’s nose, the BULLDOG van glowering across our mailbox like a punctuation mark.

“Ma’am,” the big one said to Kayla, “you want to tell me what’s going on?”

Kayla squared up halfway, the way I’d seen her square up to a cashier who double-scanned a bag of apples. She kept her hand on Walter’s shoulder like a prop she hadn’t earned. “Officer, this is Walter Anderson. He’s my boyfriend. We’re moving some of my belongings out of the house. That’s it.”

The big one had a good cop face but not a dumb one. “Have you filed for divorce or legal separation?”

Kayla’s eyes did a little fish dart to the side. The big one nodded like she’d said no out loud. “You can’t cart away community property without a legal arrangement,” he said. “Even if some of it is yours. If your husband wants to press theft charges, we can go that route. Or we can stand here and make sure you take personal items only. Clothes. Toiletries. Nothing that belongs to the household.”

It should have satisfied me, the clean cut of law on my side, the sight of Kayla disarmed by something as square as a rule. It almost did. I felt the smallest lift in my chest, a vicious little satisfaction, the kind you should be ashamed of but keep for a winter day.

“Belongings you own,” I said, the words a bad echo. “The house belongs to my mother.” The sentence had been a conversation grenade for years, and I lobbed it again, knowing exactly where it would land.

Kayla’s jaw tensed. “I raised Judy here,” she said, voice climbing. “Cleaned every corner of these rooms. Gave you the best years of my life. This is my home too.”

The cop finally let the snap in. “It’s not your house if your name isn’t on the deed,” he said. “You’re not taking furniture today. That’s the end of it.”

The Bulldogs picked up the vibe. Their faces closed over like shutters. One of them, the thin one, muttered “man, this neighborhood,” to no one in particular, and they started reversing their theft like a movie playing backwards. Chairs scuffed back across wood that had been polished for parties and holidays, boxes reappeared in the hallway, a lamp I’d hated steadied itself back on its table, its crooked shade a familiar annoyance.

“You want to press charges, Mr. Taylor?” the wiry cop asked me, pen already poised over a ticket book like the answer was probably yes.

I looked at Kayla, and then at Walter, who had pulled himself upright and was leaning against the truck with both arms across his ribs, face pale under the tan. The whole scene smelled like sweat and splinters. People had begun to collect: Darla on her porch with a coffee mug she was never going to drink from, two middle-school boys on bikes pretending to fix a chain while their ears flared like satellite dishes, Mrs. Munroe from across the street walking her ancient terrier with exaggerated slowness.

“Just get them out of here,” I said. I’d already had too many choices in one afternoon. I wasn’t ready to make any more.

Kayla’s eyes flashed. “This is bull,” she snapped, but the cop’s face said the conversation was done. She went inside with a furious little march, reappeared with suitcases that looked too small to carry seventeen years. “Open them,” I heard myself say, and I hated the part of me that wanted to catch her at something just to buy another ounce of righteousness.

She whipped them open with a theatrical zip—clothes. Shoes. Makeup bag. Under a sweater, the corner of my laptop glinted like it was on my side. I pulled it out, felt its friendly weight, suddenly furious at all the dumb passwords inside that I knew and she didn’t. “You want a computer, Kayla? Have your boyfriend buy you one,” I said, and I didn’t recognize my own voice.

Walter finally spoke, a gravelly “Jesus, Kayla, let’s just go,” and for a second I saw something I hadn’t planned on seeing: the man hurting, the man tired, the man who had, if I believed the story that came later, known my wife when they were nineteen and dumb and filled with summer. The man who had left and then come back, and how many of us can resist the stupid magnetism of what if?

But I was not ready to carry anyone else’s nuance.

They left. The cops waited until the truck door rumbled down and the Bulldog letters folded into themselves like the world’s weirdest origami. Darla went inside. The boys sped off on their bikes to narrate the drama into legend. Mrs. Munroe told her terrier he’d been a very good boy.

What remained was this: a mess in my living room. Tables dragged. Scuff marks tattooed like new veins across the hardwood. A cardboard box labeled KITCHEN sitting in the hall with its mouth open, half full of measuring cups that had measured a lifetime of nothing special. The smell of turned earth, as if something that had lived here had just been uprooted.

I stood in it awhile. I started to tidy, then didn’t. I sat on the couch because it hadn’t moved and put my elbows on my knees and let my head hang there. There is a silence that tastes metallic and new, and another that tastes like a house shutting its eyes after a long day. This was the metallic one.

At some point the silence got interrupted by the front door and the sound of my daughter’s key in the lock. Judy dropped her bag on the way in without looking and took in the staged wreck of our home with the measured horror of a teenager who’s seen worse online. “Dad,” she said, “what the hell happened?”

“Sit,” I said, and my voice was the voice fathers use when they don’t know how to be fathers.

I told her. She listened. Somewhere around “Walter,” she shrugged. “Oh. You mean Walter.” Casual as hell. And I turned to marble on the couch because the shape of her casualness was the shape of my flaw—she’d known. She’d been recruited. She’d been told by the woman I loved that I was an obstacle to be managed, not a man to be partnered. She’d gone with it. Maybe because she was sixteen and the world looks like a story you get to revise whenever you’re bored.

We argued, the way fathers and daughters argue when neither is sure the other can be forgiven. She called me controlling. I called myself responsible out loud and something much darker in the quiet of my mouth. She said her mother was allowed to be happy. I said I’d funded happiness with work boots I’d worn too long. We took turns telling a version of the truth that made the teller look reasonable.

It didn’t fix anything.

That night, the house felt like a loading dock in my chest: boxes everywhere, none of them labeled right. At two a.m., I stood at the sink and watched the streetlight turn the driveway silver. I saw the shape of Walter’s fall replayed against the ghost of my neighbor’s hydrangea and wished, stupidly, childishly, that I had a time machine for exactly two seconds of the afternoon—two seconds in which to tell myself do not hit him. I wanted to be better than the thud. I wanted to be the man with clean hands.

By morning I was a man with a plan instead.

I called a lawyer. His name was unfortunate. His grin was weaponized. He told me we’d make quick work of it. I nodded like quick and clean were synonyms, even though my living room told me different. I emptied the joint account down to a couple dollars out of spite dressed up as prudence. I drove to HR with my jaw set and signed the papers that would take Kayla’s name off the forms where names make futures tidy. Each stroke of the pen felt like sawing through a plank I’d once laid down with care.

When the divorce papers arrived at Kayla’s office two days later, my phone erupted. “How dare you?” she said, voice breaking. I let the call be a courtroom for a minute and gave myself the role of man without mercy. I made the case that fairness was not what she hoped it was. I hung up with the kind of smile that leaves a stain.

In the weeks that followed, our marriage collapsed on a public schedule, the way buildings implode in those videos where dust bowls up like a ghost leaving the carcass. The judge awarded us both the mathematically tidy answer to a messy problem: no alimony, child support until Judy was grown. Kayla’s lawyer tried a few speeches. My lawyer sliced them up and fed them back to her on a plate with the police report from my driveway as garnish.

Judy cried in court when she realized I would accept exactly what she’d asked for in a tone she hadn’t understood at the time: her mother. Kayla looked at me like I’d invented a new way to be cruel. I walked out into the sunshine of a Tuesday and let myself feel the smallest victory in the way the air didn’t hold her name anymore.

For a while, the world went quiet except for the places it didn’t. Judy lived with my mother because Kayla didn’t have the energy for a teenager and I didn’t have the softness you’re supposed to have on weeknights. I dated a woman named Sharon who liked that I didn’t talk too much, which is to say she liked the edits, not the draft. Kayla drifted in and out of our orbit like a bad satellite.

Then Walter went to jail for doing to Kayla what I had done in embryo on my driveway, except worse, except with the bruised logic of men like us, except with the practiced brutality of a man who thinks love is a door you kick. Judy told me between sobs at my kitchen table, knuckles white around a glass of water she wouldn’t drink. I nodded. I said a thing I regret. I told myself it was honest. Honesty can be its own cowardice when you weaponize it.

Time wove itself around the jagged new shape of us. I mowed the lawn. I changed the oil. I vacuumed the living room where the scuff marks had faded to a faint memory you could still catch in the right light, like chalk ghosts on a schoolyard after rain. I told myself I was fine. Good. Better, maybe.

Then, at seven in the morning on a Tuesday that smelled like laundry detergent and wet newsprint, someone pounded on my door. The kind of pounding that wants a verdict.

I opened it. Judy stood there with her bag thrown over one shoulder and the hurt in her face visible like a wound no one had bandaged right. Beside her, Kayla looked smaller than I remembered, pale under the porch eave light, hair as if it had been slept in by a stranger. She didn’t meet my eyes.

“Dad,” Judy said. “We need to talk.”

“What is it now?” I asked, because in the hours before coffee I have a way of being my worst self. “I’ve got work in an hour.”

Kayla looked at me then and everything she’d ever done wrong lined itself up behind her like soldiers, and I still had to stop myself from reaching for the version of us that had been ordinary once. “We’re in trouble,” she said, and the way she said we felt like a trick and a prayer in the same breath.

“Trouble with what?” I asked. “You get another boyfriend who—”

“Walter’s in jail,” she said. “I’m pregnant.”

The morning changed shapes like a cloud seeing a new wind. I looked at her, then at Judy, who nodded the way people nod when they’re confirming a story that they already know will ruin breakfast. Kayla kept talking like if the words rushed out fast enough I wouldn’t notice the sentence that had just knocked all the oxygen out of my living room.

“I don’t know,” she said, hands twisting, a broken choreography. “If it’s his. Or—” She looked at me like the years had all been a test and the grade had just come in. “Or yours.”

My mind went to a night months before the driveway, a night when we’d been the last pair of ghosts in a crowded bar and nostalgia had poured two drinks too many. It was a stupid, tender undoing in a house where the tension hummed like electricity in a wall. We’d woken embarrassed, more strangers than before. Now the possibility of that night had knocked and found me home.

Judy grabbed my arm. “Dad, please,” she said. “He threatened her. If he finds out she’s pregnant—he’s not stable. We can’t be at Grandma’s anymore. We need somewhere safe.” Her fingers dug into my sleeve like she was trying to anchor herself to a family. “We need you.”

There are moments when the worst versions of ourselves are also the clearest. I looked at my daughter and my wife-not-wife. I saw all the ways they had been right and wrong. I felt the part of me that forgives flare and then get tamped like a cigarette by the boot heel of another part that remembers and keeps receipts. I had a picture in my head of the courtroom, of Judy saying things she didn’t fully mean in a tone that meant them enough. I had a picture of Kayla’s hand on Walter’s face in my driveway.

“I need to think,” I said. It was the coward’s sentence and the only one available to a man deciding whether to be his worst self again.

“Can’t you just—” Judy started.

“No,” I said, and I took my arm back. She wobbled like I’d pulled a crutch.

“Dad, I’m sorry,” she said. “I’ll do anything. Please.”

I could have opened the door wider. I could have said “come in” and put the coffee on and fetched blankets and found the part of me that knows how to be shelter. I could have.

Instead I looked at my own front door like it was a piece of armor I’d paid too much for and hadn’t used enough. I told myself something about lessons and spine. I told myself I was out of sympathy like it was a thing you could spend and not a thing that gets refilled by grace if you let it.

“I said,” I repeated, “I need time to think. Go.”

Kayla’s face crumpled in a quiet I will always hate. Judy let out a sound like a rope fraying. I shut the door. The deadbolt clicked. It echoed inside the house, small and huge.

I stood there with my palm on the painted wood and listened to the sounds of departure: the half-words you say to each other when you’re trying not to cry too loudly on a porch someone else pays the mortgage for, the small crunch of gravel under shoes, the car engine turning over, the ugly relief silence brings when it erases the evidence of need.

When they were gone, I stayed there a long time, leaning into the door like if I pressed hard enough the grain would give up an answer, some natural wisdom trapped in the cellulose. It didn’t. The house listened with me. Outside, the neighborhood put a hand over the gossip’s mouth and waited to see what would happen next.

I made coffee. I poured it. I didn’t drink it. The mug sat on the counter cooling like a patient you’ve decided not to treat. I took a breath and then another. I told myself a story so simple it almost sounded true: I did what anyone would do after being pushed off a cliff.

The feeling that arrived then had no metaphor. It was a flat thing, gray as primer. It was an absence of weather. It was the feeling you put on to get through a day. I put it on and went to work.

Part II

When you sit across from a divorce lawyer whose name belongs more to late-night VHS tapes than to mahogany desks, you get the sense the universe is joking at your expense.

“Ron Jeremy,” he’d introduced himself, and I’d nearly laughed, not because it was funny but because laughing was cheaper than crying.

He wasn’t a joke, though. His smile was knife-sharp, his hands clean and steady, his voice honed by years of telling people exactly how much of their life they would keep when someone else wanted half.

“This will be child’s play,” Ron told me after I unloaded everything. Kayla. Walter. The moving truck. The police report. “She made her move too early. Tried to take property before filing papers? That’s the kind of mistake judges don’t forgive.”

I leaned forward in his office chair, the leather stiff under my arms. “I don’t want to pay her a dime more than the law demands. If she thinks Walter’s the golden ticket, let him fund her fairy tale.”

Ron scribbled in neat, square letters. “Custody?”

The word was a tripwire. My heart twitched, but my mouth was steel. “Full custody to her. I’ll pay the support until Judy’s eighteen, but that’s it. She made her choice.”

His pen stopped. His eyes flicked up. “Are you sure? Judges don’t like fathers who walk away.”

“I don’t care what judges like. I care about being done.”

I drained the joint account that night. Left exactly two dollars in it, a cruel joke wrapped in math. She’d contributed about that much anyway, I told myself, though deep down I knew marriage isn’t measured in deposits and balances. Still, spite kept me company better than guilt did.

At HR the next morning, I signed her name off my insurance, my pension, every paper that tied her to my future. With each stroke of ink, I felt lighter, sharper, crueler. By the time Kayla was served at her office, I was grinning at the thought of her face when she realized just how empty her hands were.

Her phone call came minutes later, her voice jagged with rage.

“You bastard! You emptied the account. You took my name off your insurance. How dare you?”

I swiveled in my desk chair, savoring the factory hum in the background. “Your name never belonged on my accounts. You wanted independence? Congratulations.”

“This isn’t fair! I was your wife—”

“Walter can pay what I owe you,” I said, and I hung up.

The courtroom smelled like old carpet and arguments. Kayla arrived in a neat navy dress, her lawyer, a woman named Lana, flanking her like a guard dog. Walter wasn’t there—already a bad omen for her, already a small victory for me.

Lana stood and launched into her speech. “My client has given seventeen years of her life. She deserves half of every asset.”

Ron stood without hurry, smoothing his tie. “Your honor, my client’s wife attempted to remove property from the marital home without filing for divorce. We have a police report documenting the event. Furthermore, she refuses to share half of her retirement account while demanding half of his. If the court wants fairness, fairness goes both ways.”

The judge’s gaze fell on Kayla. Stern. Heavy. “Do you have any grounds for spousal support?”

Lana tried again, listing Kayla’s years as a mother, her household contributions, her role in raising Judy. But Ron cut in, calm as if he were reading the weather. “Both parties earn similar salaries. Neither is dependent on the other. There is no financial inequity.”

The judge frowned. “Then I see no grounds for alimony.”

The words struck Kayla like a slap. Her lips parted, her shoulders hunched, but she couldn’t argue with math.

Then came custody.

“We request that Judy remain with Mrs. Taylor,” Lana said firmly.

Ron leaned into the silence like a man pulling a lever. “Actually, my client agrees. He is prepared to relinquish custody entirely, offering only the legally required support.”

The courtroom stilled. Kayla blinked in shock. Judy, seated nervously near the back, went pale. Her hands twisted in her lap, her lips trembling.

“Dad?” she whispered, her voice cracking.

I didn’t turn. I kept my eyes on the wood grain of the defendant’s table.

“Yes,” I said flatly. “That’s what you and your mother wanted.”

“Dad, no—” Judy gasped, tears spilling. She stumbled to her feet when the judge asked if she wanted to speak. Her voice shook as she tried to explain. She hadn’t meant for it to go this far. She just wanted her mom to be happy. She never wanted me to disappear.

Ron questioned her like she was a hostile witness. Each answer crumbled her more, until she sobbed, begging, “Please, Dad, don’t leave me.”

But I had already left. In my head, in my heart, I had walked out of that home the moment Walter’s name crossed Kayla’s lips.

The gavel cracked. The divorce was final. No alimony. Child support until eighteen. Custody to Kayla. Done.

Outside, the sky was so bright it mocked the drama inside. Kayla wouldn’t look at me, her face white and drawn. Judy chased me down the courthouse steps, tears in her voice.

“Dad! Please. Please don’t do this. I didn’t mean—”

I kept walking. The heartbreak in her words was a knife I deserved, but I let it cut anyway.

Weeks later, Judy was living with my mother. Kayla admitted she couldn’t handle her full time, too busy chasing Walter or licking her wounds. Judy visited me sometimes, asking to move back in. I refused. I wanted her to understand the cold she’d wished on me.

Kayla, meanwhile, learned what it meant to love a violent man. Walter ended up in jail after beating her so badly she landed in the hospital. Judy told me through sobs.

I laughed. I hated myself for it, but I laughed. “Didn’t surprise me,” I said. “I lived with her seventeen years. She can drive anyone mad.”

Judy looked at me like I’d just slapped her. Maybe I had. Maybe that’s all I had left to give.

Months rolled past, grinding like gears. I built a new rhythm. Sharon, a woman from work, became a warm distraction. Not love, not home, but comfortable.

Then one morning, pounding on my front door jolted me from half-sleep. I opened it to find Judy and Kayla. Judy’s face blotched with tears. Kayla pale, trembling, hair in knots.

“Dad,” Judy said, voice raw. “We need to talk.”

Kayla lifted her chin, voice shaking. “Walter’s in jail. But—I’m pregnant.”

The words were a wrecking ball.

Pregnant.

She explained, haltingly. It could be Walter’s. It could be mine—from one night months before, when too much whiskey blurred the edges of our collapsing marriage. She didn’t know.

Judy grabbed my arm, desperate. “Dad, please. Walter’s unstable. If he finds out, it could be worse. We can’t stay at Grandma’s anymore. We need you.”

The weight of her fingers on my sleeve was heavier than any punch I’d thrown. I saw the terror in her eyes, the regret in Kayla’s. I felt something stir in me—love, pity, instinct.

But then memory pushed harder. Judy’s shrug in the living room. Her words in court. Kayla’s hand on Walter’s cheek. The humiliation of seventeen years turned into Walter’s triumph.

“I need time to think,” I said, voice like ice.

Judy sobbed. “I’ll do anything! Please, Dad!”

I pulled my arm free.

They stared at me like I was the executioner. Maybe I was.

“Go,” I said. “You wanted me gone. Now you’ve got it.”

And I shut the door.

The deadbolt clicked. The sound of their footsteps faded. Their car drove away.

I leaned against the wood, breathing like I’d run a mile. My heart screamed in my chest. Maybe I was the villain. Maybe I was just a bitter man keeping score.

But in that moment, all I knew was this: I had chosen the cold goodbye.

Part III

The weeks after I shut the door on Kayla and Judy were heavy in a way silence can only be heavy when you know it’s filled with voices on the other side. Every time I sat on the couch, I imagined Judy’s tears staining the porch. Every time I poured a drink, I heard Kayla’s shaky voice repeating I’m pregnant.

I told myself I’d done the right thing. That door had been the last piece of armor I had left, and I wasn’t about to take it off for two people who had ripped me open before. Still, sleep didn’t come easy. When it did, it came with dreams where Judy was small again, clutching my hand at the county fair, or Kayla was laughing in the kitchen with flour on her cheek. Then I’d wake up, remember Walter, remember betrayal, and bury those dreams like they were sins.

Even from behind bars, Walter was a ghost pacing the edges of our lives. Darla—because neighbors know everything—told me Walter was awaiting trial for the assault, but he still had friends who dropped by Kayla’s place. “Sketchy types,” she whispered across the fence, pretending to weed her garden. “One of them asked me if she was still pregnant.”

I grunted, pretending it didn’t matter. But inside, it did. If Walter suspected the baby wasn’t his, that kind of man wouldn’t let it rest.

Judy came to see me one Saturday, unannounced. She stood on my porch the way she had that morning with Kayla, but this time she was alone. Her eyes were red, her backpack hanging loose from one shoulder.

“Dad, please,” she said before I even opened the door fully. “She’s not okay. She’s sick all the time. She’s scared Walter’s going to send someone after her. She’s drowning.”

“Not my problem,” I snapped, though my voice cracked in the middle.

“She thinks the baby might be yours.”

That sentence was a hammer. I stepped aside before I knew why, letting Judy in. She dropped onto the couch, hugging her knees. I sat in the armchair, keeping the space between us wide.

“You don’t get to just throw that at me,” I said.

“I didn’t,” she muttered. “She did. I’m just repeating it because you keep acting like you don’t care.”

I rubbed my face, feeling the years I’d aged in a few months. “If it is mine… then what? You think that erases everything she did?”

“No,” Judy whispered. “But it means you don’t get to erase us either.”

Sharon, the woman from work I’d been seeing, didn’t like the shadows creeping back into my house. She liked me hard-edged, decisive, not haunted.

“Why do you even listen to them?” she asked over beers at the diner. “They made their choice. Let them lie in it.”

I stared at the condensation sliding down my glass. “Because sometimes it feels like I’m punishing Judy more than Kayla.”

Sharon’s face tightened. “She chose her mother. You’re just holding her to it.”

Her words made sense in the way broken glass makes sense when you look at it: sharp, clear, but dangerous to hold.

The call came late. Judy again. “Dad,” she sobbed. “It’s Mom. She collapsed. They rushed her to County.”

By the time I got there, Kayla was pale against the hospital sheets, IV running into her arm. She looked thinner, fragile in a way that reminded me uncomfortably of the girl I’d first loved, before life had turned us into combatants.

Judy sat at her bedside, clutching her mother’s hand like a lifeline. When she saw me, relief spilled across her face.

“You came.”

“I came for you,” I corrected, though my eyes betrayed me by flicking to Kayla.

The doctor entered, clipboard in hand. “She’s dehydrated. Stress isn’t helping. The pregnancy’s still viable, but she needs rest and a stable environment.”

“Stable environment,” I repeated like it was a foreign language.

Kayla’s eyes cracked open, cloudy but focused on me. “Aaron.” Her voice was papery. “Please.”

I wanted to storm out. I wanted to say no, again, slam another door in her face. But Judy’s eyes pinned me there, begging without words. For once, she wasn’t choosing her mother over me. She was choosing survival over pride.

I exhaled. “Fine. You can both come stay. Temporarily.”

The first night they came back under my roof, the house felt alien. Kayla moved slowly, every step like she was afraid I’d shove her back outside. Judy tried to fill the silence with small talk, her teenage voice pitching high to bridge the gap.

I set rules. “You don’t touch my things. You don’t assume anything. This is not a family reunion. This is charity, and it ends the moment I say it does.”

Kayla nodded, eyes down. Judy bristled but kept quiet.

At night, I heard Kayla vomiting in the bathroom, Judy rubbing her back. I lay awake in my bed, listening to the ghosts of choices I couldn’t unmake.

It didn’t take long for Walter’s shadow to reappear. A week into their stay, someone pounded on the door at midnight. When I yanked it open, two men I’d never seen stood there, all tattoos and cigarettes.

“You got Kayla here?” one asked, grinning without humor. “Walter wants a word.”

I blocked the doorway, fists curling. “Tell Walter he lost that privilege.”

The grin widened. “He’ll be out sooner than you think. And if that kid’s not his—”

I slammed the door in his face before he could finish. My heart hammered. Behind me, Kayla stood pale and shaking, one hand on her stomach.

“I told you,” she whispered. “He won’t stop.”

For once, I didn’t feel satisfaction in being right. I felt dread.

Two weeks later, Kayla had her first proper ultrasound appointment. Against my better judgment, I went. Judy insisted.

The technician spread cool gel across her stomach, and the grainy image flickered on the screen. A tiny, pulsing heartbeat filled the room. Judy gasped softly. Kayla cried silently.

I just stared. That sound, steady and fragile, wormed past all the walls I’d built.

“Too early to tell paternity,” the doctor said when Kayla asked. “But the baby’s healthy.”

Healthy. A word I hadn’t associated with us in years.

As we left, Judy slipped her arm through mine. “You heard it, right? That’s family, Dad. Whether you like it or not.”

I didn’t answer. But I didn’t shake her off either.

That night, I sat in the living room long after everyone had gone to bed. The scuff marks from the movers were still faintly visible in the floorboards if you knew where to look. My whiskey glass sat untouched.

I thought about Walter. About Kayla. About Judy. About the heartbeat. About myself—angry, betrayed, shutting doors because it was easier than opening wounds.

Maybe I had been right to be ruthless. Maybe I had only been a coward dressed as a judge.

The baby changed everything. Or maybe it just exposed what had always been true: family isn’t clean. It’s messy, jagged, ugly, but sometimes it’s all you’ve got.

I closed my eyes and made a decision—not out of love, not out of forgiveness, but out of something deeper. Responsibility, maybe. Or just the stubborn refusal to let Walter’s ghost own the future.

Part IV

Walter got out on bail two months later.

I found out the way men like me always find out: not from lawyers, not from cops, not even from Kayla. From Darla. She was practically giddy when she caught me out by the mailbox.

“He’s back,” she said, sipping from a mug that read World’s Best Grandma even though she was only fifty-three. “Saw him last night. Black car, same cocky stride. If I were you, Aaron, I’d check the locks.”

I muttered something noncommittal, but that night I stood in the living room with a baseball bat, staring at the front door like it might sprout claws.

Kayla, pale and heavy with pregnancy now, came down the hallway and saw me. “You think he’ll come here?”

I gripped the bat tighter. “He’s a fool if he does.”

But we both knew Walter wasn’t just any fool. He was a fool who’d already taken too much from me.

The paternity test had been Kayla’s idea. “We can’t live like this,” she whispered one night, her hand on her stomach. “You deserve to know. I deserve to know.”

The results came in a week before Walter’s release. Judy was the one who opened the envelope at the kitchen table, eyes darting between us.

“It’s… it’s yours, Dad.”

Silence fell, so heavy I thought the walls might crack under it.

Kayla looked at me with tears in her eyes, but I couldn’t meet them. I was staring at Judy, who for once wasn’t casual or dismissive, but hopeful. Desperate.

My child. My responsibility. No more hiding behind anger.

I felt like the floor gave way beneath me.

The first time Walter showed up, it was late evening. Kayla was folding laundry in the living room, Judy upstairs on a video call with a friend. The knock came like thunder—three booming fists against wood.

I opened the door, bat in hand. Walter stood there, gaunt but smirking, bruises faded to yellow under his tan.

“Well,” he drawled, “if it isn’t Mr. Homeowner.”

“Get off my porch.”

He leaned casually against the frame, like he owned the damn place. “I hear Kayla’s carrying. Congrats, maybe. Could be mine, though, don’t you think?” His eyes gleamed, cruel and amused. “She always said I was the love of her life.”

Rage surged hot and stupid. My knuckles itched. But the sound of Kayla shifting behind me pulled me back.

“Walter, leave,” she said, her voice trembling but firm. “It’s over.”

He laughed. “Over? You think you walk away from me? Not how it works, sweetheart.” His eyes flicked to her stomach. “If that baby’s mine—”

“It’s not,” I cut in, voice sharp as broken glass. “Test confirmed it. Mine. Not yours.”

The smirk faltered, just for a second. Then his face twisted into something darker. “We’ll see about that.”

He shoved off the doorframe and stalked down the driveway. I didn’t breathe until his car roared away.

The next few weeks were hell. Walter lingered like smoke. We’d see his car parked a block away. Judy came home from school once in tears because Walter had followed her, leaning out his window to ask about “his baby brother.”

I filed reports. The cops nodded, wrote things down, but nothing happened. “He hasn’t done anything illegal yet,” they said. Yet.

Kayla cried often now, exhaustion written in every line of her face. I hated her for what she’d done to me. I hated her more for forcing me back into her chaos. But I hated Walter most of all—for making me feel powerless in my own home.

Sharon left. She came over one night, saw the fear hanging over the house, saw Kayla’s belly, and packed it in. “This isn’t my fight,” she said, and I couldn’t even argue.

It happened on a Saturday morning. Judy was out with my mother. Kayla was in the kitchen, trying to make pancakes even though her hands shook.

The knock came again. Louder. Angrier.

I opened the door to Walter’s sneer.

“This ends today,” he said.

“Yeah,” I agreed, stepping onto the porch, pulling the door shut behind me. “It does.”

He laughed. “What, you think you can scare me off with that bat again? You had your fun last time. I’m not leaving without what’s mine.”

I stepped closer, close enough to smell the stale smoke on his jacket. “She’s not yours. The baby’s not yours. This house sure as hell isn’t yours. You lost.”

His smirk slipped into a snarl. “She’ll never love you. She told me. Seventeen years, and you were just a safety net.”

I didn’t swing the bat. I didn’t need to. My words were weapon enough. “And where’s your love now, Walter? In a police record. In bruises on her skin. In a baby that’s not yours. You want to claim victory? You’re standing on my porch begging for scraps. That’s not love. That’s pathetic.”

His face flushed crimson. For a second, I thought he’d lunge at me. His fists twitched. But then Kayla’s voice rang out behind me: “Stop!”

She stood in the doorway, belly full, eyes fierce despite her trembling. “Walter, you don’t own me. You never did. I was stupid enough to believe you once, but not anymore. Leave us alone.”

The us in her voice hit me harder than any punch. Us.

Walter froze. Something in her tone—final, unyielding—must have cut deeper than my threats. He spat on the porch, eyes blazing, and stalked off. His car roared away, tires screeching like a tantrum.

Kayla collapsed onto the couch, sobbing. I stood frozen in the doorway, the bat heavy in my hands. Judy came home hours later, wide-eyed when she heard.

“Did he hurt you?” she asked, panicked.

“No,” I said. “Not this time.”

Kayla looked at me, gratitude tangled with shame. “Thank you,” she whispered.

I didn’t answer. I wasn’t sure if I deserved thanks, or if protecting them was simply what any man would do when cornered.

But that night, for the first time in months, the house felt… quiet. Walter’s shadow still lingered, but thinner now, like smoke after a storm.

I sat in the dark, listening to Kayla breathe in the next room, Judy’s music faint upstairs. The baby shifted in Kayla’s belly, a tiny reminder that no matter what, the future was coming.

And maybe—just maybe—I wasn’t ready to slam the door on it anymore.

Part V

The baby came sooner than anyone expected.

One night Kayla doubled over in the hallway, clutching her stomach, eyes wide with fear. “Aaron—it’s time.”

The ride to the hospital was a blur of red lights and clenched teeth. Judy sat in the back seat, whispering prayers to a God she’d never shown interest in before. Kayla’s groans filled the car, sharp, animal sounds that made the hair rise on my neck.

By the time we got her checked in, the doctors were moving fast, nurses wheeling her into a delivery room. Judy gripped my arm, terrified. “Dad—don’t leave.”

I didn’t.

Hours stretched like rubber bands. Kayla screamed, cursed, begged, cried. I stood by her bed, awkward, useless, but somehow necessary. When her hand grabbed mine, nails biting into skin, I didn’t pull away.

Then, just like that, it happened. The baby’s cry split the air, raw and loud, a sound that felt both alien and familiar.

“A boy,” the doctor announced.

They handed him to Kayla first. She sobbed, kissing his tiny forehead, then turned and held him out toward me.

I hesitated. But Judy’s eyes—wet, hopeful—pushed me forward.

The moment his weight settled in my arms, something in me cracked open. He was small, warm, helpless. My son. Mine.

For the first time in months, I felt something other than rage. I felt… whole.

The joy didn’t last long.

Two days later, as Kayla was still recovering, a nurse burst into the room. “Security’s handling it, but there’s a man outside demanding to see the patient.”

Walter.

Kayla gasped, clutching the baby tighter. Judy pressed herself against the wall, pale as paper.

I went out into the hall. Sure enough, Walter was there, arguing with two security guards, his voice carrying like thunder.

“That’s my baby!” he shouted. “You can’t keep me out!”

I stepped forward, rage and resolve twisting together. “It’s not your baby, Walter. It’s mine. Get the hell out.”

He lunged toward me, but the guards grabbed him, hauling him back. His eyes locked on mine, wild, burning. “This isn’t over, Taylor! You hear me? This isn’t over!”

I stood there, chest heaving, until they dragged him out of sight.

When Kayla and the baby were discharged, I brought them home. The house—my house—looked different with a crib in the corner and bottles on the counter. Judy hovered constantly, eager to help, as if trying to make up for every harsh word she’d thrown my way.

Kayla was quieter now, humbled. She moved carefully, spoke softly, never assuming too much. Sometimes I caught her watching me, eyes full of regret.

At night, when the baby cried, I got up more often than she did. Something about holding him in the quiet dark made me feel alive again. Like maybe I hadn’t ruined everything after all.

But Walter wasn’t done.

One evening, a brick crashed through the front window. Judy screamed. Kayla clutched the baby, heart racing. I rushed outside, but the street was empty—only the sound of an engine fading into the night.

The brick had a note taped to it. That’s my family. You can’t keep them from me.

The cops came, wrote another report, shook their heads. “Without catching him, there’s not much we can do.”

I felt rage like fire in my veins. Walter wanted a war. He’d get one.

It came a week later. I was coming home from work, the sun low in the sky, when I saw Walter’s car parked in my driveway. My heart slammed against my ribs.

Inside the house, Kayla was screaming.

I ran in, bat in hand. Walter had forced his way inside. He stood in the living room, looming over Kayla, who clutched the baby to her chest. Judy was pressed against the wall, crying.

“Get out,” I roared.

Walter turned, smirk twisted into madness. “I told you, Aaron. She’s mine. The baby’s mine. You think a piece of paper makes you the father? You’re nothing.”

I swung the bat. He dodged, lunging at me. We crashed into the coffee table, wood splintering under us. He threw a punch that rattled my jaw, but I shoved him off, swinging again. This time the bat connected with his ribs. He howled, staggering back.

Kayla screamed, “Stop, please!”

But Walter wasn’t stopping. He charged again, and for a moment I thought this was it—that one of us wasn’t walking away.

Then Judy grabbed the phone and screamed into it: “He’s here! He’s attacking us!”

Sirens wailed minutes later. The cops burst in, pulling Walter off me. He fought like a rabid dog, but they pinned him, cuffed him, dragged him out screaming threats.

“This isn’t over! I’ll kill you, Taylor! I’ll—”

The car door slammed, cutting him off.

This time, it was over.

Walter was denied bail. The assault charges stuck. With the break-in, the threats, and his history, the judge had no patience left. He was sentenced to years behind bars.

When I heard the gavel drop, I felt lighter than I had in months.

That night, back home, I stood in the nursery doorway. Kayla rocked the baby, humming softly. Judy sat beside her, tired but smiling.

For the first time in a long time, my house felt like a home.

Kayla looked up at me, eyes wet. “Aaron… I don’t expect forgiveness. But thank you—for protecting us. For protecting him.”

I leaned against the frame, arms crossed. Forgiveness still felt far away. But responsibility? That I could do.

“I’ll never forget what you did,” I said quietly. “But this boy… he’s mine. And Judy’s mine. So I’ll do what I have to. Not for you. For them.”

Kayla nodded, tears sliding down her cheeks. She didn’t argue. She just held the baby closer.

Judy stood, crossed the room, and hugged me tight. “Thank you, Dad.”

For once, I hugged her back.

Ending

Walter was gone. Kayla was humbled. Judy was back in my corner. And in my arms, I held a child who had no part in the mistakes that had poisoned us all.

Maybe I was still bitter. Maybe I’d never love Kayla again. But I had my family back, in some fractured, imperfect way.

And as the baby’s tiny hand curled around my finger, I knew this much: the man who had slammed the door shut wasn’t gone. But the man willing to open it—just a crack—was still alive too.

And maybe, just maybe, that was enough.

THE END ✅

News

I Cut Off My Family’s Secret Financial Support. They Had No Idea I’d Been Paying Their Bills… CH2

Part I The steakhouse was the kind of place that makes you walk a little straighter, as if the waiters…

Mid-labor, through the pain, I looked up—and froze. The doctor delivering my baby… was my ex. Gritting my teeth, I screamed, ‘Hurry up and pull your son out!’ CH2

Part I There’s a racket the air makes in July when it hits hot pavement and a car with no…

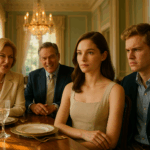

“Reborn, I smiled and said yes—to the man my sister once loved and ruined. She’ll never know what she truly lost.” CH2

Part I The halls at North Ridge High smelled like pencil shavings, old radiators, and cafeteria pizza—exactly the perfume you’d…

AT MY DAUGHTER’S BEACH WEDDING, HER FIANCE SMIRKED, “PAY $50K FOR THIS LUXURY OR VANISH FOREV… CH2

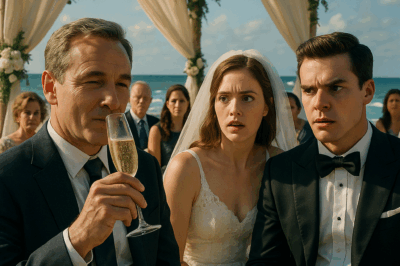

Part I The champagne flute trembled in my hand, but no one noticed. They thought it was nerves, age, maybe…

MY SECURITY COMPANY CALLED ME AT 2 AM. “SIR, THERE’S A BREACH AT YOUR MOUNTAIN CABIN… CH2

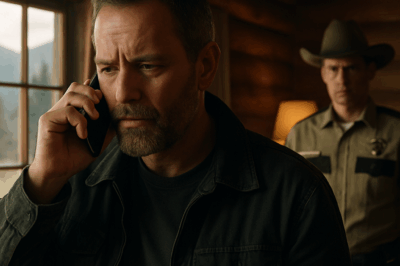

Part I When the phone rang at 2:03 a.m., I thought it was a wrong number, the kind that slips…

WS Story–I Was Driving My CEO Home .She Whispered “Don’t Stop Here-Take Me All the Way to Your Place CH2

Part I The city had that late-shift sheen—storefronts mirrored in wet pavement, traffic thinning but never sleeping, sirens distant like…

End of content

No more pages to load